Abstract

Objective

We compare Reconstructed Microvascular Networks (RMN) to Parallel Capillary Arrays (PCA) under several simulated physiological conditions to determine how the use of different vascular geometry affects oxygen transport solutions.

Methods

Three discrete networks were reconstructed from intravital video microscopy of rat skeletal muscle (84×168×342 μm, 70×157×268 μm and 65×240×571 μm) and hemodynamic measurements were made in individual capillaries. PCAs were created based on statistical measurements from RMNs. Blood flow and O2 transport models were applied and the resulting solutions for RMN and PCA models were compared under 4 conditions (rest, exercise, ischemia and hypoxia).

Results

Predicted tissue PO2 was consistently lower in all RMN simulations compared to the paired PCA. PO2 for 3D reconstructions at rest were 28.2±4.8, 28.1±3.5, and 33.0±4.5 mmHg for networks I, II, and III compared to the PCA mean values of 31.2±4.5, 30.6±3.4, and 33.8±4.6 mmHg. Simulated exercise yielded mean tissue PO2 in the RMN of 10.1±5.4, 12.6±5.7, and 19.7±5.7 mmHg compared to 15.3±7.3, 18.8±5.3, and 21.7±6.0 in PCA.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that volume matched PCA yield different results compared to reconstructed microvascular geometries when applied to O2 transport modeling; the predominant characteristic of this difference being an over estimate of mean tissue PO2. Despite this limitation, PCA models remain important for theoretical studies as they produce PO2 distributions with similar shape and parameter dependence as RMN.

Keywords: blood flow, parallel capillary networks, oxygen transport modeling, computational model, three-dimensional microvascular reconstruction

INTRODUCTION

Effectively delivering oxygen in the form of saturated red blood cells is a primary function of the microvasculature. Within skeletal muscle capillaries provide the largest surface area compared to arterioles and venules, for oxygen to diffuse out of the blood and into surrounding tissues. In combination with increased surface area, capillary networks allow for multiple transit paths for erythrocytes to deliver oxygen in a more spatially homogenous fashion. Modeling both normal and impaired oxygen transport in capillary networks can aid in the understanding of the consequences of different disease states as well as the normal functioning of living tissue (7, 13, 14). Precise models utilizing accurate reconstructions of capillary networks and direct measurements made in vivo are critical when examining perturbations to a complex system such as the microvasculature (1, 9, 15, 28). It is unclear whether or not simplified capillary network geometries such as parallel oriented vascular arrays are sufficient to represent the complex morphology observed in vivo.

Several characteristics of blood flow and network morphology have previously been identified as critical to the adequate delivery of oxygen to living tissue. August Krogh’s seminal work on tissue oxygenation identified capillary density and distance between adjacent capillaries as a limiting factor to oxygen delivery in resting and working muscle (23). Red blood cell supply rate and oxy-hemoglobin saturation directly affect tissue oxygenation and limit the amount of oxygen available for consumption by surrounding tissue (6, 8).

Capillary density, oxygen consumption, SO2, and RBC SR can be easily manipulated as variables in a computer model and values for these parameters can be readily obtained through mean measurements from histological, in vitro and in vivo means (9, 17, 25, 26). Previous efforts have been made to represent microvascular geometry using parallel networks that approximate what is seen in vivo (9, 15, 16). The resulting computer models of oxygen transport in the microvasculature have provided important insight into both the convective and diffusive delivery of oxygen to tissue. This use of parallel networks is an attractive approach given the difficulty, expense and time required to characterize capillary networks in vivo. The specific challenge of obtaining a data set that includes vascular geometry, hemodynamics and oxygen saturations has been addressed in part (11, 21); however, considerable investment in manpower and specialized equipment is still required to analyze and collect the experimental data.

The goal of this work is to compare the efficacy of using simplified, equivalent parallel capillary arrays compared to three-dimensional network reconstructions mapped using in vivo measurements. Furthermore we apply hemodynamic measurements to produce a flow model for the reconstructed networks that closely represents the flow profile observed experimentally. Using this approach, we hope to illustrate how the result of oxygen transport simulations may differ depending on the characteristics of the capillary geometry.

Materials and Methods

Intravital Video Microscopy

Capillary networks from rat EDL muscle, captured using intravital video microscopy for a previous works were used in this study. The experimental protocol used to observe and record flow conditions in the microvasculature has been described previously (12). Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley (Networks I and II) and Zucker Diabetic Fatty lean rats (Network III) were randomly selected on the day of experiment and weighed to verify a suitable mass between 140 – 180g. Animals were given an interperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital solution for anesthetic. Mechanical ventilation was used to maintain a mean breathing rate of 74 breaths per minute. Cannulas were inserted into the carotid artery, to monitor heart rate and blood pressure, and the jugular vein, to deliver supplementary saline and anesthetic as needed. EDL muscle was dissected as described by Tyml and Budreau (30), the muscle was isolated, secured with silk ligature, and reflected on the microscope stage such that the lateral side of the muscle faced the objectives. The ligature tied to the muscle was secured with surgical tape leaving the muscle in an orientation approximate to rest in situ. The muscle was kept moist with warm saline then covered with plastic film (Saran Wrap; Dow Chemical, Midland, MI, USA) and a glass cover slip to isolate it from the air. Animals were euthanized with Euthanyl Forte (Bimeda MTC, Cambridge, ON, Canada) at the completion of experimental protocols.

A Nikon Diaphot 300 inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a white light, 100W Xenon lamp for transillumination was used to visualize the EDL muscle. The intravital image was reproduced via a parfocal beam splitter fitted with 421 nm and 430 nm band pass filters. Simultaneous frame-by-frame video was captured at each wavelength using two identical computer systems, each connected to a charged-coupled device camera through real-time analog to digital capture cards. A live video output was displayed locally on closed-circuit monitors to allow the user to select regions of interest and maintain focus during capture.

Mapping Network Morphology

Intravital video sequences were used to create detailed maps of microvascular networks. Discrete networks were mapped from video sequences using custom MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) software using techniques described elsewhere (12). Briefly, a series of overlapping video sequences were recorded throughout the volume of interest, allowing for the observation of a discrete capillary network with inlet and outlet vessels intersecting with the X-Z plane of the target volume. Variance images were generated for each video sequence (19) and characteristic features in functional images were used as fiducial markers allowing for registration between overlapping fields and between different focal planes. Vessel segments within variance images were outlined using a series of automated and manual methods. Connections between vessels were identified by the user allowing for complex interconnected networks to be mapped. During network reconstruction several tools were available to aid in accurate reproduction of the experimental network including dynamic 3D generation of mapped vessels, overlaid transparent composite maps of functional images and review of intravital video to determine appropriate network connections. The resulting reconstructed networks (Figure 1) provide a detailed map of the functional morphology of contiguous networks observed in vivo.

Figure 1.

Vascular maps for reconstructed capillary networks I (top left), II (middle left) and III, shown beside equivalent parallel capillary arrays I (top right), II (middle right) and III, generated to have the same vascular volume as the reconstructions. The foreground of each network image is the arteriolar end.

Capillary Hemodynamic and Oxygen Saturation Measurements

Hemodynamic and saturation measurements were made offline from video sequences using custom software similar to that described previously (5, 6, 12, 20). Briefly, individual in focus capillary segments from each field of view were selected from variance images. Space time images were generated and used to measure velocity, hematocrit and lineal density within individual capillaries (6). Oxygen saturations at inlet capillaries were measured using a spectrophotometric method utilizing a dual camera system recording oxygen sensitive and oxygen insensitive wavelengths (5, 12). Measurements were made on a frame-by-frame basis and averaged over a 60 second collection period. Mean hemodynamic and oxygen saturation measurements were indexed to the corresponding vessels in the network reconstructions.

Equivalent Parallel Arrays

The morphology and hemodynamics of each reconstructed 3D network were quantified using simple software that provided volumetric capillary density, bounding Euclidian X, Y and Z dimensions, mean and standard deviation of capillary diameters, mean red blood cell velocity and mean tube hematocrit. These measured parameters were used as the input for a computer program that randomly generated equivalent parallel capillary arrays that matched the source 3D reconstructions in dimensions, volumetric capillary density, mean velocity and hematocrit. This method of generating parallel arrays is similar to that described by Goldman and Popel (15) to create straight unbranched vessels populated around hexagonally packed muscle fibers. A summary of the geometric measurements for each parallel capillary array is shown in Table 1. An additional, surface area matched, parallel array (PCA IISA) was created with the same vessel configuration as PCA II to compare with the volume matched model.

Table 1. Summary of network geometry parameters.

Statistical summary of vascular geometry data and capillary density.

| Volume Dimensions (μm × μm × μm) | Total Vessel Volume (μm3) | Total Vessel Surface Area (μm2) | Volumetric Capillary Density (%) | Capillary Length Density (mm × mm3) | Mean Krogh Radius (μm) | Mean Capillary Diameter (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network I | 84 × 168 × 342 | 61.2 E3 | 45.4 E3 | 1.27 | 554.2 | 25.6 ± 3.9 | 5.4 ± 0.31 |

| Parallel Network I | 84 × 168 × 342 | 61.0 E3 | 45.7 E3 | 1.26 | 565.2 | 23.6 ± 0.0 | 5.3 ± 0.37 |

| Network II | 70 × 157 × 268 | 43.3 E3 | 33.1 E3 | 1.47 | 684.8 | 23.3 ± 3.9 | 5.2 ± 0.27 |

| Parallel Network II | 70 × 157 × 268 | 43.1 E3 | 34.0 E3 | 1.46 | 727.5 | 20.8 ± 0.0 | 5.1 ± 0.34 |

| Network III | 65 × 240 × 571 | 158.1 E3 | 114.5 E3 | 1.77 | 745.3 | 21.3 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 0.35 |

| Parallel Network III | 65 × 240 × 571 | 158.0 E3 | 116.3 E3 | 1.77 | 769.9 | 20.2 ± 0.0 | 5.4 ± 0.40 |

Modeling Flow in 3D Capillary Networks

Measurements from the 3D reconstructions made in vivo were used as the basis for modeling flow in the corresponding network geometries using a method that has been described previously (10). Blood flow and hematocrit values were estimated for vessel segments for which no data was recorded by using mass balance from connected downstream capillaries. Where needed mass balance was applied incrementally from downstream bifurcations until hematocrit and velocity had been estimated for all inlet vessels.

The total network red blood cell supply rate was calculated from in vivo measurements of vessels that lay within a cross section of the network that intersected a majority of vessels for which direct hemodynamic measurements had been made. Vessels in the cross section for which no measurement was recorded experimentally were assigned a mean supply rate calculated from the measurements made in other vessels in the cross section. The resulting SRN is the total supply of red blood cells to the network volume as measured experimentally. We have previously demonstrated that (SRN) is a major factor in determining oxygen delivery to a given tissue volume and changes to SRN result in a proportional change to mean tissue PO2 (10).

Hematocrit and velocity values for inlet vessels were calculated by recursively applying a mass balance to upstream vessels until the inlet values were determined. Resulting inlet hematocrits were set for the reconstructed networks and an existing flow model (16) was applied to calculate hemodynamic conditions throughout the network vessels. Boundary pressures were adjusted iteratively at the inlets and outlets of the network to roughly match the velocities observed in vivo. SRN was matched to the experimental measurements by linearly increasing inlet boundary pressures until the target SRN was reached. Flow solutions for 3D reconstructions matched in vivo measurements of total SRN to within < 0.1%. Similarly for the parallel array networks cell velocity was linearly scaled such that the SRN was identical to the supply rate determined by the flow solution for each corresponding 3D reconstruction. The mean pressure drop across the networks for the resting flow solution were 3.00, 1.98, and 4.23 mmHg for reconstructed networks I, II and III respectively.

In order to test how perturbations to the initial parameters of consumption and oxygen delivery may alter the outcome of oxygen transport simulations between RMN and PCA networks, three conditions in addition to rest were created. As described above, the resting condition utilized the flow solution based on the total SRN for each network and a baseline consumption estimated from matching in vivo measurements of capillary SO2. Ischemic cases were created for each reconstructed geometry with specific flow solutions for each network volume where the SRN was decreased by 40%. Hypoxia utilized the same flow profile and SRN as rest but used a decreased inlet SO2 of 37.8%. Exercise cases used a higher maximum consumption rate of 6X rest and specific flow solutions for each network with a SRN 5X above the resting case. A summary of the network statistics and the other parameters used in each simulation can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2. Summary of parameters used in oxygen transport models.

Summary of network geometry and hemodynamic parameters used in oxygen transport simulations.

| RBC SR/Volume (mL RBC × mL tissue−1 × s−1) |

Entrance Saturation (%) | Consumption Rate (mL O2 × mL tissue−1 × s−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Network I | 8.3 E-4 (Exercise: 41.3 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.0 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

| Parallel Network I | 8.3 E-4 (Exercise: 41.3 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.1 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

| Network II | 8.5 E-4 (Exercise: 42.2 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.0 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

| Parallel Network II | 8.5 E-4 (Exercise: 42.2 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.1 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

| Network III | 9.4 E-4 (Exercise: 46.9 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.6 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

| Parallel Network III | 9.4 E-4 (Exercise: 46.9 E-4) (Ischemia: 5.6 E-4) |

63 (Hypoxia: 37.8) |

1.5 E-4 (Exercise: 9.0 E-4) |

Oxygen Transport Model

A finite difference model of oxygen transport developed by Goldman and Popel was used to calculate PO2 in the tissue surrounding the networks (10, 16). The flow conditions generated for each case were used as the input to the oxygen transport model to yield oxygen transport solutions describing the PO2 within the tissue volume. The volume was discretized into a series of grid points each representing 8 μm3 volume. At each time step PO2 for each volume element, P(x,y,z,t), was determined by calculating the diffusion between individual volume elements as follows: (10, 16).

| (1) |

where D, α, and M(P) are the diffusion coefficient, solubility and consumption rate of O2 respectively of the tissue. Myoglobin concentration (cMb), diffusivity (DMb), and saturation (SMb) are also addressed through Equation 1 where SMb is determined by SMb(P) = P/(P + P50,Mb) where SMb(P) is the myoglobin saturation at a given partial pressure and P50,Mb is the partial pressure at which myoglobin is 50% saturated. Oxygen levels in the blood were determined within each vessel at each axial location (ξ) using a convective mass balance equation that describes blood oxygen saturation S(ξ,t):

| (2) |

where u is the mean blood velocity, R is capillary radius, j is the oxygen flux out of the capillary at the axial location (ξ,θ), C is the O2-binding capacity of blood, Pb is the intracapillary PO2 and αb is the solubility of O2 in plasma.

The flux of O2 between capillaries and tissue is was defined as:

| (3) |

where κ is the mass transfer coefficient and Pw is the tissue PO2 at the capillary surface. κ is a function of the capillary hematocrit in a given vessel and reflects the effect of red blood cell spacing on diffusional exchange between capillary and tissue (4). The boundary condition at the capillary-tissue interface was specified as:

| (4) |

where n is the unit vector normal to the capillary surface and j is defined by Eq. 3. In the current work, the boundary condition at the tissue boundaries was specified as a zero flux boundary condition.

As described previously by Goldman et al. (15) the above O2 transport equations 1 – 4 were combined with Michaelis-Menten consumption kinetics, M = M0 P/(P + Pcr) and the Hill equation for oxyhemoglobin saturation, S(P) = Pn/( Pn + P50n) to define O2 transport within the 3D volume. The baseline oxygen consumption rate M0 (Table 2) was selected such that the resulting capillary SO2 throughout the network fit approximately with experimental observations. Values for the above constants can be found in Table 3. Distinct oxygen transport models were run for each of the 6 network geometries under each of the 4 test conditions. Simulations were run to convergence on an Apple Mac Pro workstation with approximate runtimes of 18 – 36 hours needed to approximate steady state conditions determined by a 0 slope in PO2 values over time within the corners of the simulation volume and a zero change in oxygen consumption.

Table 3.

List of constants and values used in oxygen transport simulations.

| Constant | Value |

|---|---|

| α | 3.89 E-5 ml O2 ml−1 mmHg−1 |

| αb | 2.82 E-5 ml O2 ml−1 mmHg−1 |

| C | 0.52 ml O2 ml−1 |

| D | 2.41 E-5 cm2 s−1 |

| Pcr | 0.5 mmHg |

| cMb | 1.02 E-2 ml O2 ml−1 |

| DMb | 3 E-7 cm2 s−1 |

| P50 | 37 mmHg |

| P50,Mb | 5.3 mmHg |

Results

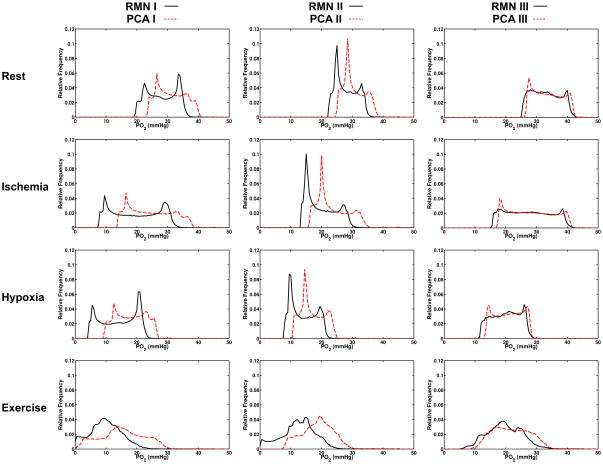

Figures 2 illustrates tissue PO2 distributions in each of the three reconstructed networks and corresponding parallel arrays for the 4 simulation cases (rest, hypoxic challenge, ischemia and exercise). In each set of simulations the tissue PO2 in the 3D capillary network reconstructions were left shifted compared to the solutions for the corresponding equivalent parallel capillary array.

Figure 2.

Tissue oxygen distribution for each set of oxygen transport simulations. Relative frequency of PO2 within the volume for reconstructed (solid black line) and parallel array (broken red line) are shown for networks I (left column), II (middle column), and III (right column) under rest (top row), ischemia (second row), hypoxia (third row), and exercise (bottom row). Ischemia was simulated by imposing a 40% decrease in RBC SR compared to rest. Inlet SO2 for hypoxia simulations was 37.8% compared to 63% at rest (a 40% relative decrease). Exercise simulations utilized a 6X increase in consumption and a 5X increase in RBC SR. Note that the parallel array for Network II has a higher minimum tissue PO2 due to a counter current vessel that spans the volume.

Mean tissue PO2 in the resting simulation for the 3D reconstructions were 28.15±4.78, 28.07±3.53 and 33.03±4.49 mmHg for networks I, II, and III respectively compared to the equivalent parallel arrays means values of 31.24±4.54, 30.57±3.44, and 33.76±4.55 mmHg (top row of Figure 2). The PO2 distributions in the ischemia cases spanned a wider range compared to rest with minimum PO2 values 3.1 – 6.51 mmHg lower in the 3D reconstructions (second row of Figure 2). The 40% flow reduction resulted in decreased mean tissue PO2 of 19.81±7.63, 19.90±4.92, and 27.48±7.06 in the reconstructions versus 24.64±6.89, 23.62±5.07, and 28.41±703 mmHg in the associated parallel arrays.

Tissue PO2 distributions in the hypoxia simulations were comparable to the ischemic case with wide ranges of PO2 values (third row of Figure 2). Again, reconstructed networks a had lower mean PO2 values of 14.22±5.84, 14.06±4.11, and 20.10±4.45 mmHg, compared to mean values determined for the parallel capillary arrays of 18.07±4.79, 17.08±3.78, and 20.95±4.35 mmHg. Exercise simulations resulted in the widest PO2 distributions (bottom row of Figure 2) with minimum PO2 values approaching 0 in reconstructed networks I and II, and parallel array I. The relatively high minimum PO2 (7.5 mmHg) in parallel array II is caused by a counter current flow vessel which was set to mimic a shorter counter current vessel segment present in reconstructed network II. Under simulated exercise conditions mean tissue PO2 in the reconstructed capillary networks was 10.07±5.37, 12.61±5.70, and 19.67±5.70 mmHg compared to 15.32±7.26, 18.76±5.25, and 21.73±5.96 in the equivalent parallel networks.

In order to illustrate the localized difference in PO2 between reconstructed networks and equivalent parallel arrays the PO2 within each volume element from RMN simulations was plotted against the corresponding value in PCA volumes for each set of networks and condition (Figure 3). Discrete points in Figure 3 have been color coded to correspond to the difference between each RMN and PCA element. Under baseline conditions the relative dispersion of matched PO2 values was small with outliers primarily being composed of volume elements in or near vessels. The spread of matched PO2 elements was higher in ischemia and hypoxia simulations with matched elements in both cases being distinctly lower in the RMN network volumes. Under the exercise conditions there was the largest discrepancy of tissue PO2 between the two types of network geometry with large portions of the volume having higher PO2 in the RMN/PCA I simulations. A relatively tighter distribution of values was seen under exercise in RMN/PCA II and III with the majority of the points showing higher tissue PO2 in the PCA simulations.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots showing the localized PO2 difference between RMN and PCA simulations. PO2 for RMN simulations is plotted against the PO2 values for the PCA simulations for each network and condition. The colormap shows the calculated difference between the two values and corresponds to the spatial depiction shown in figure 4.

To further show how the tissue PO2 differs between reconstructed and parallel networks three-dimensional difference maps were created (Figure 4). Difference maps were generated by subtracting the tissue PO2 values from the RMN oxygen transport simulations from the corresponding PCA simulations on an element-by-element basis. The resulting voxelated maps show the spatial distribution of differences in PO2 in each set of simulations. The underlying geometry from both network types are visible in the three dimensional difference maps since the largest difference in PO2 is in volume elements that are in or near capillaries. In all of the rest, ischemia and hypoxia cases tissue PO2 was uniformly lower in RMN simulations compared to PCA. The exercise cases showed some heterogeneity with RMN and PCA I having substantial regions of both higher and lower PO2 in the RMN simulation compared to the PCA.

Figure 4.

Volumetric tissue PO2 difference map for each set of oxygen transport simulations. The PO2 difference values were calculated by subtracting the transport simulation results for the PCA from the RMN simulations on an element-by-element basis. The resulting map shows how the oxygen transport simulations vary spatially where negative values represent ares where tissue PO2 was higher in the PCA simulations and positive values where PO2 was higher in RMN simulations. Each voxel element is semi-transparent allowing PO2 deep within the tissue volume to be visible. The volume elements with the largest differences are located in and around individual vessels from each of the RMN and PCA geometries. The PO2 range of colormaps was selected such that differences were easiest to view and do not encompass the entire range of values.

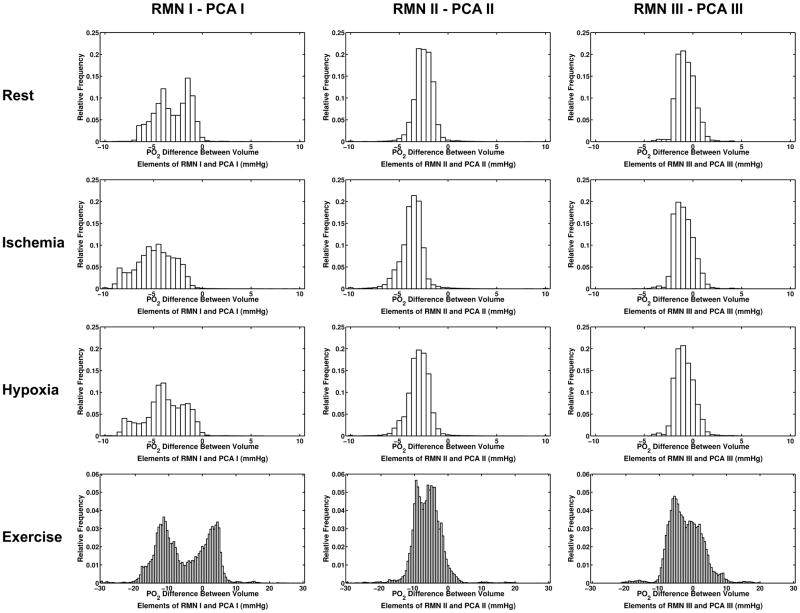

Relative difference between volume elements in each simulation was quantified by generating histograms showing the relative frequency of PO2 differences between RMN and PCA simulations (Figure 5). Bins for rest, ischemia and hypoxia ranged from −10 to 10 mmHg with a bin size of 0.5 mmHg. The larger spread of PO2 differences in exercise required bins to range from −30 to 30 with a bin size of 0.5 mmHg. Histograms show the relative frequency of the PO2 differences represented spatially in Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Histograms showing the relative frequency of the difference values calculated by subtracting PCA simulation tissue PO2 from RMN values on an element-by-element basis. The vast majority of tissue elements in rest, ischemia and hypoxia simulations have a higher PO2 in PCA simulations resulting in a high proportion of negative values in the difference histograms.

Capillary point density in reconstructed networks varied longitudinally through the volume. The arteriolar end of the vascular bed had lower capillary density increasing towards the venular end in all three reconstructed geometries. Figure 6 shows the relative capillary density in 10 μm sections taken longitudinally along each network. Reconstructed networks I and II had lower than half the capillary density at the arteriolar end than the corresponding equivalent parallel arrays. The capillary density at the arteriolar end of RMN III was closer to that of the PCA; however the number of vessels in the cross section was lower with 8 vessels in the RMN compared to 12 in the PCA cross section. Mean tissue PO2 in longitudinal X-Z planes was higher in all parallel networks due to higher capillary density at the arteriolar end, a more homogeneous distribution of vessels within the cross section, and uniform capillary density from arteriolar to venular end. Krogh radius was calculated for each 10 μm section longitudinally along each network

Figure 6.

Longitudinal capillary density for reconstructed networks and associated parallel arrays along the long axis of the network volumes. Normalized capillary density (number of vessels/mm2) was calculated for slices every 10 μm. The longitudinal position of arteriolar (A) and venular (V) ends of the network have also been indicated.

( ) and mean values are shown in Table 1. Mean Krogh radius was lower in RMN compared to the volume matched PCA in each of the three pairs of networks. Figure 7 illustrates the longitudinal difference in mean tissue PO2 for each X-Z slice between reconstructed networks and parallel arrays for the resting case.

Figure 7.

Mean tissue PO2 in each longitudinal X-Z slice for reconstructed networks (solid black line) and parallel arrays (broken red line) for resting case in networks I (top), II (middle), and III (bottom). Tissue PO2 in the parallel networks is higher due to greater capillary density at the arteriolar end and uniform spacing throughout the network volume. The lower difference in density between RMN and PCA III results in a smaller difference in mean tissue PO2 across the volume.

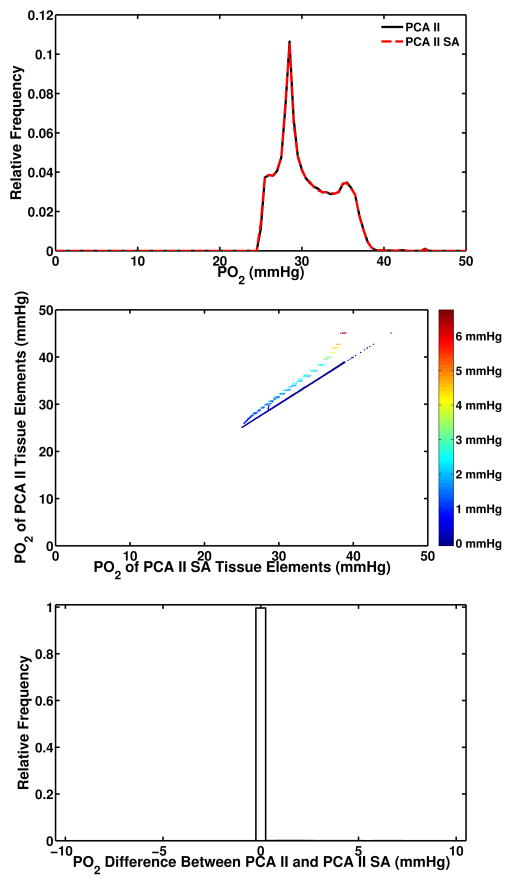

Total vascular volume and surface area for each geometry is shown in Table 1. Although vascular volume was used as a matching metric for the construction of equivalent parallel arrays the surface areas for each equivalent network also matched closely. The largest difference in total vessel surface area was 2.7% between RMN and PCA II. To test the effect of this difference in surface area an additional parallel array was constructed with surface area equal to the RMN II and the results are shown in Figure 8. The resulting oxygen transport simulation showed 0.1% difference in mean tissue PO2 and small, localized, PO2 differences in volume elements associated with vessels.

Figure 8.

An additional simulation was conducted to compare the result of using a surface area parallel array compared to a volume matched parallel array. The relative distribution of PO2 values (top) for both the volume matched (PCA II) and surface area matched (PCA II SA) overlap almost exactly. A scatter plot of PO2 values in the same voxel within each network (middle) shows that the tissue elements have the same PO2 in nearly every element. A histogram of the differences between PO2 values in matched voxels within each volume shows that nearly 100% of tissue elements have a zero difference in PO2 between the PCA II and PCA II SA simulations.

Discussion

We have presented a comparison of tissue oxygen distribution within reconstructed 3D capillary network volumes and equivalent parallel capillary arrays. Utilizing resting conditions based on in vivo measurement our model has shown that volume matched parallel capillary arrays result in a higher overall tissue PO2 in the volume of interest when compared to the 3D reconstructions. Capillary density at the upstream end of the tissue volumes was higher in the parallel capillary arrays resulting in higher tissue PO2 in tissue surrounding inlet vessels (Figure 9). The higher tissue PO2 is likely due to reduced diffusion distance between vessels resulting in higher PO2 in tissue at the inlet end of the volume. Similarly, since the outlet end of parallel array volumes have the same spatial distribution of vessels and uniform diffusion distances, we observed higher tissue PO2 levels at the venous end of parallel networks compared to the reconstructions. The more homogeneous distribution of vessels in the cross section of parallel arrays results in higher tissue PO2 within the volume due to the uniform spacing between vessels along their length. This effect can also be observed in RMN III in that the relative higher density both throughout the network and at the arteriolar end yielded results closer to the PCA III simulations. However the higher capillary density at the arteriolar end of PCA III and the uniform distribution throughout the network volume caused higher PO2 values longitudinally across the volume (Figure 7). Mean PO2 levels under resting conditions for parallel arrays (31.2, 30.6, and 33.8 mmHg) are consistent with modeling results reported by Ellsworth et al. (27 – 30 mmHg) using experimentally measured input parameters applied to parallel vessel models (9). In addition, the mean tissue PO2 in the reconstructed networks under rest conditions (28.2, 28.1, and 33.0 mmHg) is similar to average PO2 measured in spinotrapezius muscle (27.8 mmHg) using Whalen-type oxygen microelectrodes (24). The localized PO2 difference between the rest simulations (Figures 3 – 5) show higher PO2 throughout each PCA volume. In networks I and II the vast majority of volume element had a lower PO2 in RMN simulations compared to the matched PCA tissue volumes.

Figure 9.

Tissue PO2 at arteriolar end of network volumes for RMN I (top) and PCA I (bottom) illustrating volumetric regions with PO2 values above 35 mmHg for resting conditions. PO2 values below 35 mmHg are transparent to show the range of interest.

Under simulated ischemia, hypoxia and exercise conditions we also observed higher mean tissue PO2 in each of the three parallel array models compared to the corresponding 3D reconstructed networks. Lower flow in the ischemic simulations yielded an increased difference in mean tissue PO2 between reconstructed and parallel networks compared to rest. Larger differences in mean tissue PO2 between reconstructions and parallel arrays compared to rest were also seen in simulated hypoxia models. Ischemia and hypoxia caused a higher variation in element-by-element PO2 differences between the two types of network, however again the vast majority of volume elements had lower PO2 values throughout the volume in RMN simulation compared to PCAs.

Of the four input conditions exercise was the only perturbation to create regions of anoxia in a test volume. Mean tissue PO2 for reconstructed networks (10.1 and 12.6 mmHg) was lower than previous calculated values for mild exercise (17 mmHg) but consistent with heavy exercise conditions (12 mmHg) (9). Similarly Goldman et al. reported mean tissue PO2 of 23.2 mmHg for simulated working conditions in fiber-structured vessels (analogous to parallel networks in this study) which is somewhat higher than what was found under exercise conditions in the equivalent parallel arrays (15.3 and 18.8 mmHg). There are however some differences in the blood flow and oxygen consumption values used in this study compared to previous reports. For comparison, the 10 fold increase in consumption applied by Goldman and Ellsworth (9, 15) results in an oxygen consumption of 15.7E-4 (mL O2 × mL tissue−1 × s−1); 70% higher than that used in the present study. Furthermore the 5 fold blood flow increase described previously (15) yields a RBC SR of 62E-4 (mL RBC × mL tissue−1 × s−1), which is 50% higher than the RBC SR per unit volume used for exercise conditions in this study. With these differences in mind the relative scaling of blood flow and oxygen consumption is comparable between this and previous studies. Increasing consumption and blood flow caused greater heterogeneity in PO2 distribution spatially throughout the network (Figure 5). Localized differences in vessel position due to the different underlying geometries created large variations in the tissue PO2 surrounding individual vessels. Even given these localized differences the majority of tissue elements in each set of exercise simulations had lower PO2 values in the RMN simulations compared to PCA.

An additional consideration for interpretation of these results is the presence of a single counter current vessel in Network II which was mimicked in the equivalent parallel array. The imposed counter current vessel spans the full length of the parallel volume, compared to a short counter current segment in the corresponding reconstructed network. This likely prevented oxygen levels from falling to 0 in the parallel array II exercise simulation. Counter current exchange between this vessel and other vessels increased the mean tissue PO2 substantially compared to the 3D reconstruction. It has been noted previously that the presence of counter current flow significantly affects the distribution of oxygen within a volume (15). It is important to note that while the difference in mean tissue PO2 between parallel and reconstructed networks increased in each of the three perturbed cases compared to rest, the overall magnitude of the shift was relatively similar between parallel and reconstructed networks as was the underlying shape of the paired distributions in each case.

A previous study compared several variations of computer generated capillary networks to study the effect of anastomoses and tortuosity on oxygen delivery (15). Goldman et al. applied oxygen transport simulations using straight unbranched capillary networks, similar to those used in the current study, and showed that networks with anastomotic vessels yielded mean tissue PO2 values 1 mmHg higher than the comparable simulations with straight unbranched vessels. Similarly networks with tortuous vessels resulted in a mean tissue PO2 1 mmHg higher than straight unbranched networks. This effect did not appear to be additive, in that network cases combining tortuosity and anastomoses did not further increase mean tissue PO2 beyond 1 mmHg above the straight and unbranched case. Goldman et al. concluded that the presence of tortuous and anastomotic vessels increased mean tissue PO2. In the present study we found that parallel arrays (equivalent to straight unbranched networks) delivered more oxygen when compared to the reconstructed networks. From this it is reasonable to conclude that adding tortuosity and anastomoses to our parallel arrays would further increase the difference compared to real networks reconstructed from in vivo data. Ellsworth et al. also noted that the homogeneity of vessel SO2 increased longitudinally in a parallel vessel model of oxygen transport (9). The cause of this uniformity was attributed to a high degree of diffusional exchange amongst adjacent capillaries causing a convergence of SO2 levels towards the venular end of the network. This effect is likely to similarly impact tissue PO2 longitudinally causing more uniform gradients of oxygen perpendicular to the direction of flow resulting in higher tissue PO2 throughout the tissue volume.

Morphological differences between reconstructed networks and parallel arrays, specifically varying capillary density longitudinally along the network in RMN versus a more uniform distribution of vessels throughout the volume in PCA, have a marked impact on oxygen delivery. Mean capillary point density is higher in PCA networks and does not vary longitudinally (Figure 6); this effectively reduces the diffusion distance from vessels to tissue particularly at the arteriolar end of the PCA networks which results in higher PO2 within the tissue volume. In addition to the effect of higher point density, the tessellation of vessels within the parallel arrays creates a more uniform vessel spacing which further serves to reduce diffusion distance within these volumes. This difference in diffusion distance is also illustrated by the mean Krogh radius which was smaller in each PCA compared to the paired RMN (Table 1). Due to these factors, parallel networks that utilize a homogeneous and ordered distribution of vessels throughout the network volume will have a shorter mean diffusion distance to tissue resulting in higher tissue PO2 when compared to simulations based on reconstructed vascular geometries.

The method used to generate parallel networks was based on the absolute capillary volume in the corresponding reconstructed network. Alternative metrics could be used to create parallel arrays that could be considered equivalent. We consider producing networks with equal vascular volume to be a realistic approach though we acknowledge it does not directly compare to the approach of using the number of vessels per cross sectional area. Furthermore since mean capillary diameter was also used as an input to create the volume matched PCAs the total vessel surface area was within 2.7% of the reconstructed networks in each case. An additional simulation using a surface area matched PCA showed almost no difference between the volume matched equivalent (Figure 8) illustrating how the location of vessels has an impact on oxygen delivery with the volume. An additional benefit of using volume matched network geometries is that the total consuming tissue volume is maintained between the parallel array and the network reconstruction; use of a metric such as point density would cause a mismatch in the consuming volume for parallel arrays based on the reconstructed networks used in this study.

The equivalent parallel arrays in the present work were generated by randomly assigning vessel locations within a hexagonally tessellated grid. Given the size of the tissue volume and the resulting tessellation, each of the equivalent parallel arrays used in this study is one of numerous possible configurations. For example, there are 3003 different possible vessel configurations for PCA I given a tessellation grid of 14 different vessel positions for 8 discrete vessels. Although it is impossible to know a priori which configuration would best match oxygen transport simulation results from the corresponding reconstructed vasculature, it is worth examining a subset of random configurations to determine whether or not varying vessel orientation in parallel arrays will have an impact on oxygen delivery. To interrogate this problem, ten additional random configurations were generated for the network I volume and resting oxygen transport simulations were run for each. The resulting PO2 distributions for each random configuration (Figure 10) showed some variability, with mean tissue PO2 ranging between 31.0 and 31.6 mmHg. The small differences in PO2 between the random configurations tested demonstrate that within a given random array, vessel position itself will have some minor effect on oxygen delivery and mean tissue PO2. Regardless of the methods employed to generate a parallel array it is important to realize that the collection and characterization of a given network with respect to specific geometry and hemodynamic parameters was first accomplished experimentally in order to identify representative values to apply to the resulting generated arrays. We would assert that models are made more realistic when they employ a representative range of network morphologies and input parameters; ideally reconstructed 3D geometries and flow conditions calculated using direct in vivo measurements would be used. The limited number of reconstructed networks used in this study certainly does not encompass all of the diversity that may be seen in living muscle. However, we believe the ability to utilize specific cases and accurately represent a degree of variation is a step forward from the application of mean values to represent what is certainly a widely variable system that exhibits a distinct heterogeneity of vascular density and relative flow distribution.

Figure 10.

To demonstrate the variability in PO2 distributions due to alternate random vessel configurations ten additional resting simulations were conducted based on the PCA I volume. Each random configuration (R1 – R10) shown above represents a unique solution and illustrates the variability in oxygen transport simulations that are due to changing vessel placement within the tessellation grid.

Considerations

The approach used in this study to create parallel capillary arrays addresses a common type of synthetic vessel network used in oxygen transport modeling. Generated networks of this type have been used to simulate vessels found in skeletal muscle and as such, the conclusions of this study should be considered with the understanding that the results presented here may not apply to more complex vascular structures such as those found in kidney, liver, heart and brain (3, 18, 22, 27, 29). These results do however point to the importance of obtaining detailed experimental data and, in particular, capillary geometry. Future studies should consider the impact of synthetic networks particularly when simulating complex geometries with non-parallel vascular orientations.

Several studies have used synthetic networks to simulate skeletal muscle vascular that include tortuosity and branching segments (2, 15). This study does not address the effect of these characteristics when applied to synthetic networks, though there is some evidence to suggest that simply adding tortuosity and branches to a continuous density array does not substantially affect oxygen delivery (15). Additional work will need to be done in order to examine this question in more detail and to compare synthetic geometries that include these features with equivalent reconstructed networks. Furthermore, the inclusion of longitudinal capillary density variations in synthetic geometries that utilize branching and tortuous segments may serve to minimize the different results in oxygen transport simulation shown between reconstructed and synthetic networks in this study. Provided that data describing variations in longitudinal capillary density was available, synthetic networks could be generated to incorporate such variations while maintaining vascular volume either measured experimentally or estimated from stereological measurements.

Conclusion

Using a computational oxygen transport model we have demonstrated that the source and structure of the underlying vascular geometry will produce distinctly different results. We have shown this effect in discrete network volumes ranging from 268 to 571 μm in length. The application of 3D reconstructed capillary networks and matching blood flow profiles created using in vivo data, yielded lower mean tissue PO2, and lower mean cross sectional PO2 throughout the tissue volume, compared to parallel arrays generated using equivalent volumetric and hemodynamic parameters. When examined on an element-by-element basis rest, ischemia, and hypoxia conditions RMN had lower PO2 values spread uniformly throughout the sample volumes compared to PCA. These perturbations to oxygen delivery and consumption increased the observed difference in tissue PO2 between reconstructed and parallel source geometries resulting in larger differences in PO2 between tissue elements. Simulated exercise caused significant localized heterogeneity in element-by-element tissue PO2 differences suggesting that the underlying geometry between RMN and PCA has a more profound affect under this condition. The results of this study illustrate the value of using precise representations of vascular structures when modeling oxygen transport. In every case tested, PCAs had a higher mean tissue PO2 that was caused by higher PO2 values spread uniformly throughout the tissue volumes. The range of differences in mean tissue PO2 between RMN and PCA simulations varied from 2.2% in the network III rest simulations to 52% between the network I exercise simulations. These results clearly suggest that at this length scale, volume matched equivalent parallel arrays yield different oxygen transport solutions than reconstructed networks collected from in vivo experiments. These finding are tempered somewhat by the observation that tissue PO2 distributions from parallel arrays and the paired reconstructions were very similar both in shape and in the relative changes resulting from the three test perturbations. Continued efforts to directly measure larger and more complex microvascular networks will provide a broader scope of input data allowing existing models to reflect the structural and functional variability seen in vivo.

Perspective

The use of reconstructed 3D capillary networks can provide a more precise spatial picture of oxygen delivery within the microvasculature under a variety of normal and pathological conditions. Heterogeneities in oxygen tension within a given geometry could be used to explore angiogenesis and other physiological responses to hypoxic challenges. The future possibility of combining several distinct network geometries with models of larger vessels could aid in producing more integrated models of blood flow and O2 delivery in whole tissue as well as providing a framework for exploring control mechanisms that involve oxygen sensing in the microvasculature. Existing parallel array models continue to have great utility when simulating large vascular beds although modelers should attempt to incorporate observed diversity in morphology and blood flow. The availability of reconstructed network geometries and associated in vivo data sets, will improve the predictive power of existing models and facilitate the validation of the resulting solutions.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP 102504 (C.G. Ellis) and the National Institute of Health HL089125 (D. Goldman and C.G. Ellis). The authors would also like to thank Stephanie Milkovich for her work analyzing experimental data and reconstructing three-dimensional networks.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- 3D

three-dimensional

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- PO2

partial pressure of oxygen

- RBC

red blood cell

- SO2

oxygen saturation

- SR

supply rate

- SRN

network supply rate

References

- 1.Beard DA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Advection and diffusion of substances in biological tissues with complex vascular networks. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2000;28:253–268. doi: 10.1114/1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard DA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Modeling advection and diffusion of oxygen in complex vascular networks. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2001;29:298–310. doi: 10.1114/1.1359450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassot F, Lauwers F, Fouard C, Prohaska S, Lauwers-Cances V. A novel three-dimensional computer-assisted method for a quantitative study of microvascular networks of the human cerebral cortex. Microcirculation. 2006;13:1–18. doi: 10.1080/10739680500383407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggleton CD, Vadapalli A, Roy TK, Popel AS. Calculations of intracapillary oxygen tension distributions in muscle. Mathematical biosciences. 2000;167:123–143. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(00)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis CG, Ellsworth ML, Pittman RN. Determination of red blood cell oxygenation in vivo by dual video densitometric image analysis. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H1216–1223. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis CG, Ellsworth ML, Pittman RN, Burgess WL. Application of image analysis for evaluation of red blood cell dynamics in capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1992;44:214–225. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(92)90081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis CG, Goldman D, Hanson M, Stephenson AH, Milkovich S, Benlamri A, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. Defects in oxygen supply to skeletal muscle of prediabetic ZDF rats. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2010;298:H1661–H1670. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01239.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellsworth M, Ellis C, Popel A, Pittman R. Role of Microvessels in Oxygen Supply to Tissue. News Physiol Sci. 1994;9:119–123. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1994.9.3.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellsworth ML, Popel AS, Pittman RN. Assessment and impact of heterogeneities of convective oxygen transport parameters in capillaries of striated muscle: experimental and theoretical. Microvasc Res. 1988;35:341–362. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(88)90089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser GM, Goldman D, Ellis CG. Microvascular Flow Modeling using In Vivo Hemodynamic Measurements in Reconstructed 3D Capillary Networks. Microcirculation. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser GM, Milkovich S, Goldman D, Ellis CG. Mapping 3-D functional capillary geometry in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H654–664. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01185.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser GM, Milkovich S, Goldman D, Ellis CG. Mapping 3D Functional Capillary Geometry in Rat Skeletal Muscle In Vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01185.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman D. Theoretical models of microvascular oxygen transport to tissue. Microcirculation. 2008;15:795–811. doi: 10.1080/10739680801938289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman D, Bateman RM, Ellis CG. Effect of decreased O2 supply on skeletal muscle oxygenation and O2 consumption during sepsis: role of heterogeneous capillary spacing and blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2277–2285. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00547.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman D, Popel AS. A computational study of the effect of capillary network anastomoses and tortuosity on oxygen transport. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2000;206:181–194. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman D, Popel AS. Computational modeling of oxygen transport from complex capillary networks. Relation to the microcirculation physiome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;471:555–563. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4717-4_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groom AC, Ellis CG, Wrigley SJ, Potter RF. Capillary network morphology and capillary flow. International journal of microcirculation, clinical and experimental/sponsored by the European Society for Microcirculation. 1995;15:223–230. doi: 10.1159/000179022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guibert R, Fonta C, Plouraboué F. Cerebral blood flow modeling in primate cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1860–1873. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japee SA, Ellis CG, Pittman RN. Flow visualization tools for image analysis of capillary networks. Microcirculation. 2004;11:39–54. doi: 10.1080/10739680490266171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japee SA, Pittman RN, Ellis CG. A new video image analysis system to study red blood cell dynamics and oxygenation in capillary networks. Microcirculation. 2005;12:489–506. doi: 10.1080/10739680591003332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamoun WS, Chae S-S, Lacorre DA, Tyrrell JA, Mitre M, Gillissen MA, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Munn LL. Simultaneous measurement of RBC velocity, flux, hematocrit and shear rate in vascular networks. Nat Methods. 2010;7:655–660. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamoun WS, Schmugge SJ, Kraftchick JP, Clemens MG, Shin MC. Liver microcirculation analysis by red blood cell motion modeling in intravital microscopy images. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55:162–170. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.910670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A. The number and distribution of capillaries in muscles with calculations of the oxygen pressure head necessary for supplying the tissue. J Physiol (Lond) 1919;52:409–415. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lash JM, Bohlen HG. Perivascular and tissue PO2 in contracting rat spinotrapezius muscle. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H1192–1202. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.6.H1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathieu-Costello O, Potter RF, Ellis CG, Groom AC. Capillary configuration and fiber shortening in muscles of the rat hindlimb: correlation between corrosion casts and stereological measurements. Microvasc Res. 1988;36:40–55. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(88)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter RF, Groom AC. Capillary diameter and geometry in cardiac and skeletal muscle studied by means of corrosion casts. Microvasc Res. 1983;25:68–84. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(83)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichold J, Stampanoni M, Lena Keller A, Buck A, Jenny P, Weber B. Vascular graph model to simulate the cerebral blood flow in realistic vascular networks. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1429–1443. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Secomb TW, Hsu R. Simulation of O2 transport in skeletal muscle: diffusive exchange between arterioles and capillaries. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1214–1221. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su S-W, Catherall M, Payne S. The influence of network structure on the transport of blood in the human cerebral microvasculature. Microcirculation (New York, NY : 1994) 2012;19:175–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyml K, Budreau CH. A new preparation of rat extensor digitorum longus muscle for intravital investigation of the microcirculation. International journal of microcirculation, clinical and experimental/sponsored by the European Society for Microcirculation. 1991;10:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]