Abstract

Objective

To compare the body image and weight perceptions of primary care patients and their physicians as a first step toward identifying a potential tool to aid physician communication.

Methods

Patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 (n = 456, 66% female) completed body image and weight status measures after office visits; physicians (n = 29) rated the body figures and weight status of these same patients after office visits.

Results

Controlling for BMI, female patients and their physicians showed little or no difference in body figure selection or weight status classification, whereas male patients were significantly less likely than their physicians to self-identify with larger body figures (z = 3.74, p < .01) and to classify themselves as obese or very obese (z = 4.83, p < .0001).

Conclusion

Findings reveal that physicians and female patients have generally concordant views of the patient’s body size and weight status, whereas male patients perceive themselves to be smaller than do their physicians. The discrepancy between male patient and physician views is especially evident at increasingly larger body figure/weight status categories.

Practice Implications

When counseling male patients on weight loss, it could be helpful to assess body image and use this information to raise patient awareness of their size and to facilitate communication about weight.

Keywords: men’s health, primary care, body image, obesity, weight management

1. Introduction

In light of the United States’ obesity epidemic [1,2] and associated preventable morbidity and mortality, economic burden, and emotional distress [3–6], there is a national commitment to better understanding effective prevention and treatment strategies [7]. Factors impacting the quality of patient-physician communication are receiving increased attention in the literature due to the known link between effective communication and patient outcomes such as adherence to treatment [8–10], recall and understanding of medical advice [10–12], and health outcomes [10,13,14]. Differences in patient-physician perceptions and expectations are believed to pose a barrier to effective communication about weight loss and may hinder patient motivation to make health behavior changes [15,16], making exploration of patient and physician body perceptions an important area for study.

Comparison of patient and physician views in the specific area of body perceptions is a rich yet relatively untapped area of investigation. A parallel line of work has focused on parental perceptions of children’s weight status given the important role of parents in providing messages to their children about weight [17–19]. Likewise, physicians are conduits for communication about weight with their patients. The linkage of self-evaluation data with appraisal by an objective observer, in this case, linking patient body perception with physician judgment of patient body size has the potential to yield information for the obese patient’s primary care encounter. Clinically, recognition of a problem is often a precursor to the mobilization of resources to work toward change [20]. Given the linear relationship between BMI and mortality [21], it seems critical that obese patients accurately perceive their size in order to understand the full range of health implications as well as then having a greater likelihood of acting on advice given at a primary care visit.

Research on patient’s accuracy of weight perceptions has generally compared measured BMI with self-perceived weight status [22–24] and in one case, with body image figure ratings [25]. The current study proposes to build on existing research by examining both self-perceived weight status and body image given that they are related, yet independent constructs. Body image is a multi-dimensional construct which includes perception of body size and weight status [26] but more broadly represents the way individuals think about and experience their bodies [27]. Examination of both body image and weight status has the potential to yield a richer picture of the patient’s view of his or her body than examining either construct alone. Further, comparing patient body image and weight perceptions to those of their physicians represents a novel approach to evaluating concordance of body perceptions.

The purpose of the current study is to compare the body perceptions of primary care physicians and their patients as a first step toward identifying a potential tool to aid physician-patient communication about weight. This study seeks to: 1) describe the distribution in body figure ratings and weight status classification as rated by physicians and patients, and 2) evaluate the level of concordance between physicians and patients in body figure ratings and weight classification ratings.

2. Methods

2.1 Study Setting

Data were collected as part of a larger study examining patient and physician communication about weight and obesity. The research was conducted in primary care practices located in non-metropolitan (less than 50,000 residents) areas of a single Midwestern state during June and July of 2003. The patient populations of these practices are approximately 90% Caucasian [28]. Primary care sites chosen for this study were a convenience sample of physician practices actively participating in the Kansas Physicians Engaged in Prevention Research (KPEPR) practice-based research network. The non-random sample of physicians in this study practiced in 20 separate clinical groups geographically dispersed across all non-metropolitan regions of the state. In all but one of the primary care study sites, only one physician within the practice actively participated in the research project. In that one practice, two physicians participated. All of the practices were general internal medicine or family practices. None were specialty practices exclusively dealing with weight management or another specific disease state.

2.2 Participants

To participate in the study, patients had to be at least 18 years of age, English-speaking, BMI ≥ 30, not pregnant or early post-partum, and not acutely ill, emotionally distressed, or cognitively impaired. Eligibility criteria for physicians included being in active practice, seeing patients at least four days per week, agreeing to patient recruitment and study protocols, and willingness to work with a medical student acting as a research assistant within the practice.

2.3 Procedure

Medical students received research training and served on-site at the primary care practices during the six-week data collection period. Medical students recruited the first obese patient of each morning and afternoon outpatient session, so that as many as two patients per day from each practice might participate. Height and weight were anthropometrically measured by clinic staff and used to calculate BMI, of which a value of 30 or greater constituted obesity. At the end of office visits, medical students asked eligible patients to participate in a brief anonymous survey, described as a questionnaire to increase understanding of how patients and physicians work together to confront weight issues. Medical students explained that patients had no obligation to participate, that their responses would be kept confidential from their physician and office staff, and that their decision would not affect their healthcare. Medical students then administered a paired survey to the patients’ physician during routine breaks that same day, for a maximum or two patient-matched surveys per day. The pairing of surveys occurred through coding so that patient-physician data could be linked for analysis while protecting the patient’s identity. Study protocol specified that medical students administer the survey to physicians to minimize the possibility that physicians would examine the medical chart containing patient height/weight/BMI while completing the survey. At the same time, physicians were aware that only obese patients were under study (as opposed to patients representing a full range of body sizes) given the focus of the research project on patient and physician communication about weight and obesity. Every participant gave verbal consent. Because prior studies conducted within these practices using the same recruitment methods showed a 97% response rate [28], we did not collect information on potential participants who were approached but declined the invitation to participate. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

2.4 Measures

Body image

Patients were presented with the gender-appropriate set of 9 body image drawings ranging from extremely thin to extremely obese and asked to select the drawing closest to their current figure [29]. Body image figures were pictured in order from smallest to largest on a single 8 ½ × 11 inch page. The body image instrument was chosen for its strong psychometric properties, including excellent inter-rater reliability (alpha = 0.95) and good content, convergent, and concurrent validity [29]. The instrument was designed to appear realistically human and ethnically neutral, maximizing its suitability for use with participants from multiple ethnic backgrounds. Physicians used this same instrument to select the drawing that most closely resembled the current figure of the patient.

Weight Status Classification

Patients were asked to classify their current weight as either very underweight, a little underweight, weight is just right, a little overweight, very overweight or obese, or very obese. This weight classification scheme was adapted from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey [30] by modifying the fifth descriptor to include the term obese and adding a sixth descriptor, very obese. Modification of fifth and sixth descriptors was undertaken to minimize a measurement ceiling effect given the exclusive focus of the study on obese patients. Physicians classified the current weight of the patient using this same scale.

BMI

Anthropometrically height and weight were used to calculate BMI using the formula: (weight in pounds * 703)/height in inches2.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

To describe the body perceptions of patients and physicians, we first calculated the mean BMI for all patients who chose a given figure and assigned their BMI to the figure chosen. This calculation was then done separately for male and female patients. The process was then repeated using the BMI for all patients assigned a given figure by their physicians. This procedure yielded two mean BMI ratings for each figure drawing: one comprised of patient self-ratings and the other comprised of physician ratings of the patients. Second, this same procedure was repeated to examine BMI based on weight status categorization chosen by patients and physicians. We calculated the mean BMI for all patients who chose a given weight status classification and assigned their BMI to the weight category chosen. This calculation was then done separately for male and female patients, and the procedure was repeated using the BMI for patients assigned a given weight category by their physicians.

Because our patient sample was selected to be obese, over 90% of patient ratings and over 97% of physician ratings, fell between figures 5–9. The majority of the remaining patients (7.24% of total patient sample) and all of the remaining physicians (1.6% of physician sample) selected figure 4. Of the remaining participants, Figure 3 was chosen by 2 male and 2 female patients, and figure 2 was selected by 1 female patient. Given the small proportion of patients and physicians choosing figures 1–4, no calculations were performed for figures 1–4. Similarly, no calculations were performed for the weight categories very underweight or a little underweight given that these categories were not selected by either physicians or patients meeting study inclusion criteria.

Level of concordance between physicians and male and female patients in body figure ratings and weight classification ratings was evaluated in two ways. First, correlational analysis among BMI and figure and weight status ratings by patients and physicians was performed. This analysis was conducted for the entire patient sample and for men and women separately. Because most of our measures were ordered, but could not be assumed to have equal intervals, Spearman rank-order correlations were performed. Second, level of concordance was evaluated using generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis. GEE analysis was chosen over a more traditional approach to evaluating agreement, such as Kappa analysis, because each doctor rated multiple patients while each patient rated only him or herself. GEE analysis enabled physician responses to be modeled as repeated given that each physician rated multiple patients. GEE analysis yields a z value comparable to the R squared term yielded by regression analysis.

Significant associations were explored between physician and patient body perception and weight status ratings and patient BMI, patient gender, and patient age. Difference scores between patient and physician ratings of body perception and weight status were calculated (physician ratings minus patient ratings) and used to created derived variables which were submitted to the GEE analysis. A significance level of 5% was used for all tests. All analyses were performed using SAS Software System version 9.01 following entry into an Access database.

3. Results

3.1 Distribution in body figure and weight classification by physicians and patients

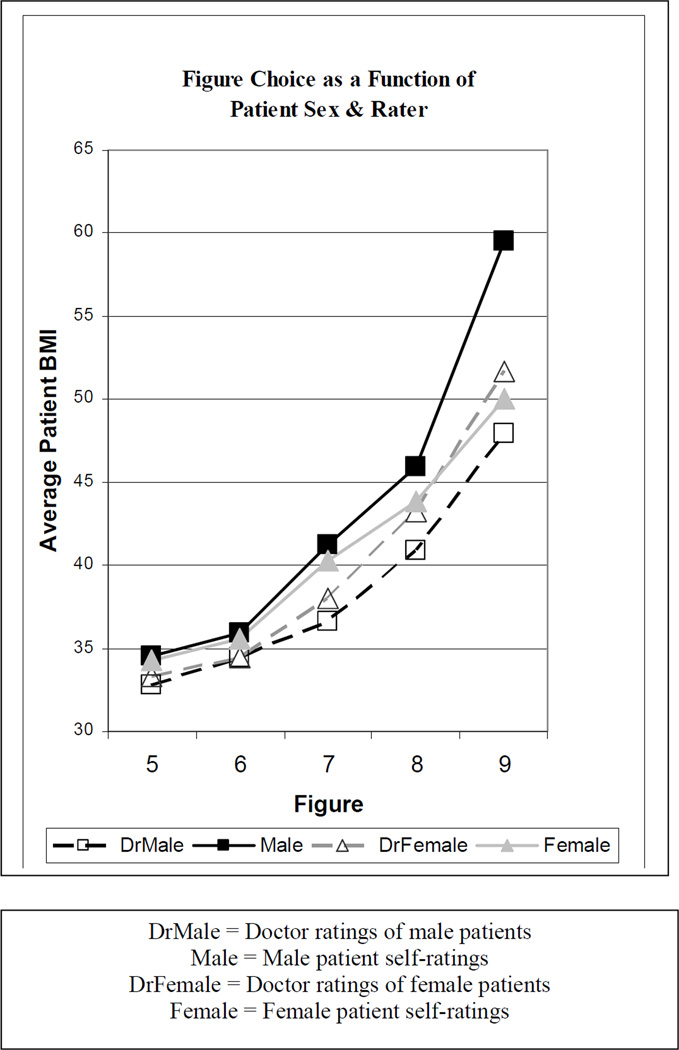

Male patients generally selected smaller figures for themselves than did their physicians. For example, a male patient with a BMI of 41 tended to select Figure 7 to represent his current figure, whereas a physician tended to choose Figure 8 for that same patient (see Table 1). In addition, the gap between men and their physicians widened with each increasingly larger image beginning with the seventh figure, whereas this gap between women and their physicians at the larger end of the scale was not observed (see Figure 1). Male patients appeared less likely than their physicians to select the largest figures on the scale. For example, physicians selected figure 9 for male patients with a BMI of 48 whereas male patients did not select figure 9 until a BMI of 60 (see Table 1). In addition, physicians chose figures 8 or 9 for their male patients in 25 cases, whereas male patients identified with figures 8 and 9 in only 6 cases (see Table 1). Female patients and physicians appeared more similar in their ratings, with physicians selecting figure 9 for female patients with a BMI of 52 and female patients self-identifying with figure 9 at a BMI of 50. Likewise, physicians chose figures 8 or 9 for their female patients in 89 cases, whereas female patients identified with figures 8 and 9 in 71 cases.

Table 1.

Patient BMI Based on Figure Rating by Patients and Physicians

| ALL PATIENTS | |||||

| Doctor Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 91 | 106 | 135 | 74 | 40 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 33.1 (3.2) | 34.4 (3.5) | 37.5 (4.9) | 42.7 (6.1) | 50.8 (8.2) |

| Patient Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 130 | 123 | 88 | 46 | 31 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 34.4 (3.6) | 35.7 (4.0) | 40.5 (6.0) | 43.9 (7.6) | 51.0 (8.6) |

| MALE PATIENTS |  |

|

|

|

|

| Doctor Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 40 | 45 | 39 | 16 | 9 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 32.8 (2.1) | 34.4 (3.4) | 36.6 (4.8) | 40.9 (7.4) | 47.9 (5.3) |

| Patient Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 71 | 40 | 17 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 34.5 (3.0) | 35.9 (4.3) | 41.2 (4.4) | 45.9 (5.8) | 59.5 (6.4) |

| FEMALE PATIENTS |  |

|

|

|

|

| Doctor Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 51 | 61 | 96 | 58 | 31 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 33.3 (3.9) | 34.4 (3.6) | 38.0 (4.9) | 43.2 (5.6) | 51.7 (8.7) |

| Patient Ratings | |||||

| # of ratings | 59 | 83 | 71 | 43 | 28 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 34.3 (4.3) | 35.6 (3.9) | 40.3 (6.4) | 43.8 (7.8) | 50.0 (8.4) |

Figure 1.

BMI Based on Figure Ratings by Patients and Physicians

A similar pattern was observed when comparing physician and patient weight status classifications. The spread in BMI across weight status categories as rated by male patients and physicians increased incrementally (1 point difference in BMI between male patients and physicians for a little overweight; 2 points for very overweight/obese; 4 points for very obese), whereas the spread between female patients and physicians remained consistently 1 point apart across weight categories (see Table 2).

Table 2.

BMI Based on Patient Weight Status Categorization by Patients and Physicians

| Just Right | A Little Overweight |

Very Overweight or Obese |

Very Obese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL PATIENTS | ||||

| Doctor Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 0 | 125 | 245 | 84 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | -- | 32.7 (2.7) | 37.4 (5.1) | 46.8 (8.1) |

| Patient Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 5 | 165 | 245 | 39 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 32.5 (2.4) | 34.0 (4.6) | 39.0 (6.2) | 47.9 (8.9) |

| MALE PATIENTS | ||||

| Doctor Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 0 | 48 | 86 | 20 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | -- | 32.6 (2.4) | 35.7 (3.9) | 45.1 (7.5) |

| Patient Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 2 | 91 | 52 | 8 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 32.9 (4.3) | 33.6 (3.4) | 38.2 (4.6) | 49.0 (9.5) |

| FEMALE PATIENTS | ||||

| Doctor Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 0 | 77 | 159 | 64 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | -- | 32.7 (2.8) | 38.3 (5.4) | 47.4 (8.3) |

| Patient Ratings | ||||

| # of ratings | 3 | 74 | 193 | 31 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 32.3 (1.4) | 34.4 (5.8) | 39.2 (6.6) | 47.6 (8.9) |

3.2 Concordance between physician and patient body figure and weight ratings

Differences between male patient and physician perceptions were confirmed by GEE analysis. Specifically, patient and physician figure choice differed as a function of patient gender when controlling for BMI. Whereas female patients’ figure judgments were largely consistent with those of their physicians, male patients’ judgments were not (z = 3.74, p < .01). This pattern is demonstrated in Figure 1, in which the gap between the judgments of male patients and physicians becomes more pronounced as figure size increases. An identical pattern was observed in the comparison of physician and patient weight status classification. Controlling for BMI, female patients and their physicians showed little or no difference in weight status classification, whereas male patients were significantly less likely than their physicians to classify themselves as obese or very obese (z = 4.83, p < .0001). Correlations among patient and physician figure ratings, weight status ratings, and BMI tended to be in a positive direction and were of moderate strength; these associations are displayed in Table 3. Stronger associations were observed between physician ratings of body figures and weight status (r = .73) than patient classification (r = .60) of those same variables. In addition, the concordance between physicians and patients was stronger for body figure ratings (r = .57) than for weight status ratings (r = .39).

Table 3.

Spearman Correlations of Patient and Physician Figure Ratings, Weight Status Ratings, and BMI

| Variable | Dr Body Figure Rating |

Pt Body Figure Rating |

Dr Wt Status Rating |

Pt Wt Status Rating |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | |||||

| Pt body figure rating |

0.57 | ||||

| Dr weight status rating |

0.73 | 0.48 | |||

| Pt weight status rating |

0.44 | 0.60 | 0.39 | ||

| BMI | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.57 | |

| Men | |||||

| Pt body figure rating |

0.55 | ||||

| Dr weight status rating |

0.70 | 0.51 | |||

| Pt weight status rating |

0.41 | 0.58 | 0.36 | ||

| BMI | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.59 | |

| Women | |||||

| Pt body figure rating |

0.55 | ||||

| Dr weight status rating |

0.74 | 0.47 | |||

| Pt weight status rating |

0.40 | 0.55 | 0.38 | ||

| BMI | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

Note: p < 0.0001 for all correlations

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to compare weight and body image perceptions of primary care physicians and their patients as a first step toward identifying a potential tool to aid patient-physician communication about weight. Findings reveal that female patients and their physicians have generally concordant views of the patient’s body figure and weight status, whereas male patients perceive themselves to be smaller than their physicians. The discrepancy between male patient and physician views became more marked with increasing body size/weight status. Our findings add to the evidence base that men, particularly obese men, are more likely to underestimate their weight status than women [22–24]. Our study extends previous literature by using a broader definition of size (e.g., body image) and employing different methods (e.g., anchoring patient body perception to physician ratings).

In benchmarking patient ratings against physicians’, we make the assumption that physician ratings are more accurate. This assumption derives from a medical model in which physicians are viewed as experts [31]. Primary care physicians are trained to use BMI to measure obese status and gain clinical experience pairing BMI’s with bodies [32]. In doing so, they develop clinical judgment. Clinical judgment is a cornerstone of clinical practice and is known to supersede clinical guidelines [33]. We are not aware of any studies which examine the accuracy of physician perceptions which would provide evidence either for or against our implicit position that physicians are more accurate than patients in judging body size and rating weight status. Within the context of our study in which physician perceptions are the anchor for accuracy, greater concordance equates with greater accuracy.

Although the focus of our study was not to prove that doctors are more accurate, examination of the data suggests it is likely. It was rare for our participants to rate their weight as “just right:” it occurred 5 times. However, it was even rarer for physicians to rate patients as “just right:” it never occurred. Another way of evaluating this issue is to look at the appropriateness of weight classification based on mean BMI (Table 2). Arguably, it is less appropriate to use the descriptor “a little overweight” to classify the weight status of individuals in our sample than the descriptors “very overweight or obese” or “very obese.” Doctors were more likely to classify male patients in these latter two categories (69%) than male patients (39%) were themselves. Consistent with our general study results, doctors and female patients used the latter two categories at the same rate (74%). Similarly, it is arguably less appropriate to select the smaller body image figures (e.g., < 5) to represent obese individuals. In the approximately 10% of participant data excluded from analyses, doctors were less likely to select the smaller figures (3%) than were participants (10%).

Physician use of the body image scale to rate patient body figure corresponded well with their classification of patient weight status. When rated by patients, the association between body figure and weight status diminished, presumably because the patient takes more information into account when evaluating body image, such as their internal experience of their bodies and their overall self image [34,35]. Body figure ratings may be external and one-dimensional when rated by observers, whereas for patients body image is multidimensional and includes a broader self-concept than weight classification alone [26,27]. Although weight status categories are useful, they may not fully capture how obese patients see themselves.

Although research to date has not yet explored whether patient-physician perceptual differences lead to less behavior change by patients who are counseled, we believe there is a risk that a difference in perception between patients and physicians could interfere with the communication process. Social psychological research supports the prediction that people will choose to interact with people or in environments where their self concept is verified instead of challenged [36]. Individuals will therefore seek out or avoid certain kinds of information and environmental settings and are likely to ignore, reject, or distort information inconsistent with their self concept [37]. Although speculative, it is possible that discrepancy in body perceptions, such as that observed between male patients and physicians in the present study, could partially explain men’s reluctance to seek medical care [38]and receipt of less obesity treatment [39–41]. Patients may also minimize physician advice if they don’t view their size to be of the same magnitude as their physicians.

Given that awareness of the full magnitude of a problem could be a critical factor in moving a patient toward change [42–44], we speculate that self-perception of a body figure smaller than the doctor’s evaluation could inhibit patient response to treatment recommendations, especially in light of the challenges incumbent in making successful weight change [45]. It is important to note that some literature suggests that inaccurate perception of oneself (e.g., positive illusion) is a foundation for good psychological functioning [46,47]. To our knowledge, this concept has not yet been applied to the obesity literature, but we acknowledge that lack of recognition of absolute level of obesity may indeed buffer self-esteem and protect against distress. However, we believe that the benefit to be gained by more accurate perception in motivating change outweighs the cost of temporary psychological discomfort. In fact, it is the creation of intra-psychic conflict and mental discomfort within the patient which is believed to spark action [20].

4.2 Conclusion

This study has implications for enhancing the identification of obesity and improving communication about weight issues between male patients and their physicians. Improving the accuracy of body perceptions and better aligning the views of male patients and physicians might contribute to better follow-through on physician advice by patients and enhanced delivery of weight management interventions by physicians. Male patients might be more receptive and adherent to weight management advice if they recognize their size to be of the same magnitude as their physicians do; in turn, physicians may be more likely to become partners in their obese male patients’ care if they feel their advice will be taken seriously.

Physician discussion of weight with patients is based on multiple factors, including health status, age, sex, education, and BMI [39,40,48]. This suggests that BMI alone is not predictive of counseling, but that multiple variables factor into the process of whether counseling will occur. One of the strengths of the present study is its novelty in evaluating physician perceptions of patient body size, and as such, physician perceptions have not been examined as a predictor of communication about weight to date. The present study lays the foundation for further examination of how body perceptions affect the communication process. Regardless of what factors physicians base their conversations about weight upon, we contend that these discussions will miss the mark in cases when patients under-estimate the magnitude of their size. Future work on best practices for addressing discordance with patients using the tools of body image, weight status, and BMI are warranted.

This study contains a number of strengths and limitations. A primary strength is the linking of patient and physician data taken on the same day, which minimizes recall bias. Second, this study utilized objective measures of height and weight, lending greater accuracy than self-report. Third, the adequate number of both obese men and women in the patient sample enabled us to examine the study variables as a function of gender. A limitation of the study was its convenience sample of a relatively homogeneous ethnic sample in a defined geographic region. Future work with more diverse samples would strengthen the external validity of the results. Likewise, future work must produce a gold standard anchoring a specific BMI range to each figure to increase the practical application of body image assessment in primary care work. Further, this study was not designed to examine the effect of physician gender on body perceptions and concordance, and the low number of female physicians in our study sample limited our ability to conduct such analyses. However, we believe this is an exciting area for future study and the logical next step in this line of research.

Two potential limitations in the present study are important to be taken into consideration when planning future research. First, we did not calculate response rate given a previously high response rate within this research network using similar recruitment techniques, but it is possible that differences could exist due to response bias. Second, we make the assumption that absolute size is problematic based on the linear relationship between BMI and mortality; however, it would be important to explicitly assess the extent to which patients view their weight as a problem in a future study. It is possible that a patient who rates his body image as a 7 believes his weight is just as much a problem that needs to be addressed as a patient who rates his body image as a 9. Yet, because we know clinically that patient perception of problem-severity often precedes behavior change [42–44], particularly with difficult changes such as weight loss [45], we believe that body figure size and recognition of a weight problem are connected. However, future study is needed to empirically test our implicit assumption that body figure size is connected to either perception of a problem or willingness to take action toward correcting the problem.

4.3 Practice Implications

In general, overweight and obese men report receiving less advice than obese women concerning their weight [39–41] and report spending less time with their physicians than their non-overweight counterparts [49]. Given that men are less likely than women to seek medical care [38] and engage in preventive lifestyle behaviors such as avoiding fat and eating fiber, dieting, and attaching great importance to healthy eating [50], men are at greater risk of not recognizing or addressing the impact of weight on their overall health. This delay in treatment-seeking may lead to increased medical costs and decrease the likelihood that treatment is effective. Therefore, exploration of tools to improve the primary care encounter about weight issues with obese men is an important area of continued study.

When broaching issues of concordance with patients, this study suggests that body figure size could be a better construct to discuss than weight status given the stronger association between physician and patient ratings of body figure compared to weight status. Pictures (e.g., body image figures) might be perceived more neutrally than terms (e.g., weight status) which could have different interpretations or meanings. Likewise, because body image is a multi-dimensional construct, it is more inclusive and captures not only perceived weight but also global experience of one’s body [27]. Further, discussion of size anchored to body image rather than weight status may lend itself better to a clinical focus on behavior changes in diet and exercise rather than just the need to lose weight; this subtle shift in message-framing may be linked to better outcomes, especially among some racial/ethnic minorities [51,52].

Silhouette-based body image scales, such as the one employed in this study, may provide an easily-understood vehicle by which physicians and male patients can compare their perceptions. Evidence that the body image scale investigated in this study is positively associated with anthropometric markers, such as BMI, can give practitioners confidence in using this tool. Brief motivational interviewing [53–60], followed by presentation of body figures anchored to BMI markers of obesity, are recommended to boost recognition of body figure size among male primary care patients and enhance patient-physician communication about weight loss.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge medical student research assistants and physicians in the Kansas Physicians Engaged in Prevention Research practice-based research program at the University of Kansas Medical Center. We would also like to thank Ken Resnicow, PhD, Ed Ellerback, MD, MPH, and Kim Kimminau, PhD for valuable advice and assistance during study planning and implementation phases, and Martha Montello, PhD for editorial assistance.

This study was funded by the Sunflower Foundation of Topeka, Kansas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;288(14):1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282(16):1519–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, Stevens J, VanItallie TB. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282(16):1530–1538. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers A, Rosen JC. Obesity stigmatization and coping: relation to mental health symptoms, body image, and self-esteem. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(3):221–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. Washington DC: Author; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pi-Sunyer FX. Medical hazards of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):655–660. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services. Health People 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett EE, Grayson M, Barker R, Levine DM, Golden A, Libber S. The effects of physician communications skills on patient satisfaction; recall, and adherence. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(9–10):755–764. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrity TF. Medical compliance and the clinician-patient relationship: a review. Soc Sci Med [E] 1981;15(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/0271-5384(81)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roter DL, Hall JA, Katz NR. Relations between physicians' behaviors and analogue patients' satisfaction, recall, and impressions. Med Care. 1987;25(5):437–451. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CK, Polis E, Hadac RR. Characteristics of the initial medical interview associated with patient satisfaction and understanding. J Fam Pract. 1981;12(2):283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henbest RJ, Stewart M. Patient-centredness in the consultation. 2: Does it really make a difference? Fam Pract. 1990;7(1):28–33. doi: 10.1093/fampra/7.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews DA, Suchman AL, Branch WT., Jr Making "connexions": enhancing the therapeutic potential of patient-clinician relationships. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(12):973–977. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-12-199306150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Befort CA, Greiner KA, Hall S, et al. Weight-related perceptions among patients and physicians: how well do physicians judge patients' motivation to lose weight? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1086–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEvoy DM. Minnesota physicians' attitudes and behaviors regarding weight. Minn Med. 2005;88(9):48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutelle K, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Mothers' perceptions of their adolescents' weight status: are they accurate? Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1754–1757. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman E, Hinden BR, Khandelwal S. Accuracy of teen and parental reports of obesity and body mass index. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):52–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang JS, Becerra K, Oda T, et al. Parental ability to discriminate the weight status of children: results of a survey. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e112–e119. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelber RP, Kurth T, Manson JE, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Body mass index and mortality in men: evaluating the shape of the association. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(8):1240–1247. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang VW, Christakis NA. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(4):332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuchler F, Variyam JN. Mistakes were made: misperception as a barrier to reducing overweight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(7):856–861. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):345–350. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Villegas A, Madrigal H, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, et al. Perception of body image as indicator of weight status in the European union. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14(2):93–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2001.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn KJ, JFitzgibbon M. Body image and obesity risk among black females: A review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02893804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher S. Development and Structure of the Body Image. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greiner KA, Engelman KK, Hall MA, Ellerbeck EF. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in rural primary care. Prev Med. 2004;38(3):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulvers KM, Lee RE, Kaur H, et al. Development of a culturally relevant body image instrument among urban African Americans. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1641–1651. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vol. 99. Washington DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services; [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel VL, Arocha JF, Kaufman DR. Expertise and tacit knowledge in medicine. In: Sternberg RJ, Horvath JA, editors. Tacit knowledge in professional practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):933–949. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garfield FB, Garfield JM. Clinical judgment and clinical practice guidelines. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(4):1050–1060. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300103113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molloy BL, Herzberger SD. Body image and self esteem: A comparison of African-American and Caucasian women. Sex Roles. 1998;38:631–643. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson JK. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swann WB, Jr, Stein-Seroussi A, Geisler RB. Why people self-verify. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;62:392–401. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swann WB., Jr . To be adored or to be known? The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 408–448. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodwell DA, Cherry DK. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2002 summary. Adv Data. 2004;(346):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282(16):1576–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Honda K. Factors underlying variation in receipt of physician advice on diet and exercise: applications of the behavioral model of health care utilization. Am J Health Promot. 2004;18(5):370–377. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.5.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loureiro ML, Nayga RM., Jr Obesity, weight loss, and physician's advice. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(10):2458–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIntosh J, McKeganey N. Identity and recovery from dependent drug use: the addict's perspective. Drugs: education, prevention, and policy. 2001;8(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans L, Delfabbro PH. Motivators for change and barriers to help-seeking in Australian problem gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 2005;21(2):133–155. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-3029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matzger H, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. Reasons for drinking less and their relationship to sustained remission from problem drinking. Addiction. 2005;100(11):1637–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew AM, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):220–233. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(2):193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor SE, Brown JD. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: separating fact from fiction. Psychol Bull. 1994;116(1):21–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Physician counseling about exercise. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282(16):1583–1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hebl MR, Xu J, Mason MF. Weighing the care: patients' perceptions of physician care as a function of gender and weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(2):269–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisle F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yancey AK, Simon PA, McCarthy WJ, Lightstone AS, Fielding JE. Ethnic and sex variations in overweight self-perception: relationship to sedentariness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(6):980–988. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yancey AK, Wold CM, McCarthy WJ, et al. Physical inactivity and overweight among Los Angeles County adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emmons KM, Rollnick s. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scales R, Miller JH. Motivational techniques for improving compliance with an exercise program: skills for primary care clinicians. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2(3):166–172. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200306000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poirier MK, Clark MM, Cerhan JH, Pruthi S, Geda YE, Dale LC. Teaching motivational interviewing to first-year medical students to improve counseling skills in health behavior change. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(3):327–331. doi: 10.4065/79.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field C, Hungerford DW, Dunn C. Brief motivational interventions: an introduction. J Trauma. 2005;59(3 Suppl):S21–S26. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000179899.37332.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorpe M. Motivational interviewing and dietary behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(2):150–151. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shinitzky HE, Kub J. The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(3):178–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]