Abstract

Background

Quitting smoking is often associated with weight gain and prenatal cessation may lead to increased gestational weight gain (GWG). Although previous reports have suggested a link between prenatal smoking cessation and GWG, no studies have examined the relationship between cessation and guideline-recommended GWG, and there is little information about the relationship between the timing of prenatal cessation and GWG. Thus, we examine GWG among women in a community prenatal smoking cessation program and assess the relationship between the timing of prenatal cessation GWG.

Methods

Pregnant women health care clinics serving economically disadvantaged women who participated in a smoking cessation intervention offered free of charge, self-reported weight, and provided biochemical verification of smoking. Relationships between duration of cessation and GWG were evaluated in t-tests and regression models. GWG was calculated from self-reported weight before pregnancy and self-reported weight at the last visit before delivery.

Findings

Women who quit earlier during pregnancy had greater GWG (16.9 ± 7.5 kg) than did those who never quit (13.6 ± 8.9). After adjusting for timing of weight assessment and prepregnancy body mass index, however, GWG was not different between women who did and did not quit.

Conclusion

Quitting earlier in pregnancy is associated with greater GWG, but women who do and do not quit do not differ on total GWG. Despite increased GWG with early cessation, the maternal and fetal health benefits of prenatal smoking cessation outweigh risks of potential risks of excessive GWG.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is an important preventable health risk behavior, and current estimates suggest that 10% to 12% of women smoke during pregnancy. Women who smoke during pregnancy have lower incomes and are often younger and less well-educated than women who never smoked or who quit smoking during pregnancy (Kendrick et al., 1995; Martin et al., 2007; Suellentrop, Morrow, Williams, & D'Angelo, 2006; Windsor et al., 1993). Although prenatal smoking cessation has well-documented benefits for maternal fetal health (Bernstein et al., 2005; Butler, Goldstein, & Ross, 1972), a recent review of cessation interventions for pregnant women concluded that cessation intervention succeeds with only 6% of pregnant smokers (Lumley et al., 2009). Thus, efforts to understand factors associated with prenatal smoking cessation are needed to support cessation efforts among pregnant women.

Typically, smoking cessation is associated with weight gain. Smokers gain approximately 4.5 kg during the first 6 months after smoking cessation (Hudmon, Gritz, Clayton, & Nisenbaum, 1999; Klesges et al., 1997), although some smokers gain even greater amounts of weight after cessation (Perkins et al., 2001; Williamson et al., 1991). Given the link between smoking cessation and weight gain, it is possible that quitting during pregnancy could result in gaining more gestational weight. Excessive gestational weight gain (GWG), or weight gain during pregnancy that exceeds the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009) increases the risk of obstetric complications (Cedergren, 2006, 2007) and is associated with greater risk for overweight among offspring (Oken, Rifas-Shiman, Field, Frazier, & Gillman, 2008; Schack-Nielsen, Michaelsen, Gamborg, Mortensen, & Sorensen, 2010; Wrotniak, Shults, Butts, & Stettler, 2008).

To date, several reports have documented a link between prenatal smoking cessation (Adegboye, Rossner, Neovius, Lourenco, & Linne, 2010; Favaretto et al., 2007; Groff, Mullen, Mongoven, & Burau, 1997; Mongoven, Dolan-Mullen, Groff, Nicol, & Burau, 1996; Washio et al., 2011) or reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy (Favaretto et al., 2007) and increased GWG. For example, Washio and colleagues (2011) found that women who quit smoking gained 2.8 kg more than did those who continued to smoke, although this difference in GWG was not significant after adjusting for prepregnacy BMI. Similarly, Favaretto and colleagues (2007) reported that women who quit after conception gained more gestational weight than did never smokers. Thus, quitting relates to greater GWG than continuing to smoke.

Despite data suggestive of an association between smoking cessation and weight gain, several questions remain. First, the IOM revised its guidelines on GWG in 2009 and now recommends weight gains of 11 to 16 kg for normal weight (i.e., BMIs 18.5–24.9), 7 to 11.5 kg for overweight (i.e., BMIs 25.0–29.9), and 5 to 9 kg for obese women (BMIs ≥ 30.0) to mitigate the consequences of inadequate or excessive GWG to mother and fetus (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009). Given that these revised guidelines include an upper limit for obese women, and that obese women are more likely than normal weight women to gain excessive weight during pregnancy (Linne, Dye, Barkeling, & Rossner, 2004), it is important to examine factors related to excessive GWG. To date, the relationship between prenatal smoking cessation and the current IOM guidelines regarding GWG based on prepregnancy BMI has not been evaluated. Second, it is unclear whether the timing of cessation during pregnancy and GWG are related. For example, women who quit smoking earlier in pregnancy may gain more than those who quit closer to delivery. Finally, previous reports describing the relationship between smoking cessation and GWG have not consistently been based on biochemically validated cessation rates. Indeed, only one study provided biochemical validation of smoking status on all women (Washio et al., 2011). In some studies, only a subset of women's smoking status has been validated by cotinine or expired-air carbon monoxide (CO; Groff et al., 1997; Mongoven et al., 1996), whereas others used only self-report of smoking status (Favaretto et al., 2007).

Accordingly, we examined GWG among women smokers enrolled in an evidence-based community prenatal smoking cessation program for low-income women (reference blinded by WHI editors for peer review) in which all women provided biochemical validation of smoking status. We hypothesized that women who continued to smoke would be more likely to experience inadequate GWG, whereas those who quit would be more likely to have excessive GWG. We also examined the relationship between the timing of biochemically validated cessation during pregnancy and GWG.

Methods

Participants

Pregnant smokers were recruited to a smoking cessation intervention funded primarily by state master tobacco settlement funds. Participants who were smoking or had recently quit smoking were referred directly from obstetrical providers inhospital-based clinics serving primarily Medicaid-insured individuals, other community clinics, drug and alcohol treatment centers, school-based programs for pregnant teens, health plan pregnancy case management programs, or viewed flyers publicizing the program and contacted the program directly. Additional details of the Stop Tobacco in Pregnancy (STOP) prenatal smoking cessation program have been described elsewhere (Reference Blinded by WHI Editors for Peer Review). Briefly, the STOP program was designed to encourage cessation among women from lower income groups. Intervention was offered free of charge and all pregnant women who smoked or had recently quit smoking seen in the community clinics participating in STOP were eligible to enroll in the cessation intervention program.

Participants for the current study were all women enrolled in STOP during the period when weight data were being collected and thus have data on prepregnancy weight available for analysis (n = 357). All women were pregnant with singletons and there were no additional exclusionary criteria. Participant characteristics by end of pregnancy smoking status are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics by Smoking Status at the End of Pregnancy.

| Quitters (n = 76) | Continuing Smokers (n = 281) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (y) | 23.9 (5.5) | 25.6 (6.2) | .02 |

| Weeks gestation at assessment | 38.6 (2.5) | 38.2 (2.7) | .26 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 26.1 (6.8) | 25.6 (6.6) | .52 |

| Baseline cigs/day | 1.0 (.6) | 1.4 (.6) | <.0001 |

| Prepregnancy nicotine dependence(0–10) | 2.5 (2.2) | 3.8 (2.7) | .0006 |

| %(n) | % (n) | ||

| Married | 36.8 (28) | 33.1 (93) | .54 |

| White | 54 (41) | 69 (194) | .01 |

| Prepregnancy weight status | .70 | ||

| Under weight (BMI < 18) | 7.9 (6) | 7.5 (21) | |

| Normal weight (BMI = 18–25) | 44.7 (34) | 52.3 (147) | |

| Overweight (BMI = 25.1–30) | 19.7 (15) | 17.1 (48) | |

| Obese (BMI > 30.1) | 27.6 (21) | 23.1 (65) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Smoking Cessation Intervention

Prenatal smoking cessation treatment was delivered individually and in-person in community health clinics where participants received prenatal services and included treatment components recommended by the Public Health Service Guideline for general smoking cessation (Fiore et al., 2000; Fiore et al., 2008). Participants were rewarded with inexpensive baby items for attendance.

Smoking Status

At each intervention visit, women provided an expired-air CO sample and reported on recent cigarette use. Smoking status was documented at the final session before delivery and was based on the self-report and biochemical validation with CO (Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). End of pregnancy smoking cessation was defined as the self-report of no cigarettes in the past week and a CO level of no more than 8 ppm. If either self-report or CO indicated smoking, women were classified as continuing smokers. In contrast, quitters were women who self-reported zero cigarettes in the past week and had a CO level of 8 or fewer ppm at the final intervention session before delivery. All women also completed the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence at enrollment in the cessation intervention (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

Weight, Prepregnancy BMI, and GWG

Maternal height and prepregnancy weight were collected by self-report at intake and GWG was obtained by review of medical charts. Prepregnancy BMI was calculated as prepregnancy weight (kg) divided by height (m2). GWG was determined by subtracting prepregnancy weight from the final weight available, and was defined as excessive according prepregnancy BMI per IOM guidelines (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009). Because the timing of the final weight measurement varied across subjects, and because the time between this assessment and delivery would affect total GWG, we calculated time between final assessment and delivery. Time of assessment before delivery was defined as the number of weeks between the measurement of final weight and a woman's delivery date. This variable was then used as a covariate in analyses of GWG.

Data Analysis

We first generated descriptive statistics on demographic characteristics, GWG, timing of weight assessment, nicotine dependence, and prepregnancy BMI for all participants. Women who stopped smoking during pregnancy, women who quit (Q), and those who did not, women who continued to smoke (CS), were compared using chi-square or Fisher exact tests and two-sample t-tests for categorical or continuous data, respectively. To examine the effect of smoking cessation during pregnancy on GWG, we regressed GWG on smoking status, controlling for prepregnancy BMI and time between assessment and delivery. We also evaluated the effect of nicotine dependence on GWG.

Next, we divided women according to when during pregnancy they quit smoking. The median number of days before delivery that women had been quit was 54, and women who quit before the median were considered early quitters; those quitting less than 54 days before delivery were considered late quitters. The GWG of women who quit early, late, and not at all were compared using a regression model, with controls for prepregnancy BMI and timing of weight assessment, which is included to account for variance in the length pregnancy among women.

Finally, we evaluated the relationship between smoking cessation and the 2009 IOM guidelines for GWG. Each woman's GWG was categorized as inadequate, adequate, or excessive according to her self-reported prepregnancy BMI. We then used a Mantel-Haenszel test to evaluate the effect of cessation on weight gain across these categories. To adjust for prepregnancy BMI and the amount of time women had been abstinent, we ran a logistic regression model for ordinal responses (inadequate, adequate, and excessive) controlling for prepregnancy BMI and duration of prenatal smoking cessation, defined as the time abstinent from cigarettes.

Results

On average, women gained 14.0 ± 8.6 kg during gestation and delivered at 38.3 ± 2.7 weeks. Overall, 21.1% of women (n = 76) had stopped smoking before delivery, and there were no differences between those who did and did not quit smoking in marital status, prepregnancy BMI, or length of gestation. However, older, White women were less likely to quit smoking than were younger, non-White women (p = .02 and p = .01; Table 1).

Prenatal Smoking Cessation and Total GWG

As expected, prepregnancy BMI was significantly associated with GWG, with women who began pregnancy at higher BMIs having smaller total GWG (p < .0001). As shown in Table 2, women who quit smoking had greater GWGs (15.3 ± 7.4 kg) than did those who continued to smoke throughout pregnancy (13.6 ± 8.9 kg), although the difference in total GWG was not significant overall (p = .12) or after adjusting for prepregnancy BMI and time between assessment and delivery (p = .10). Nicotine dependence also was not related to GWG (p = .19).

Table 2. Total GWG and GWG According to IOM Guidelines by Smoking Status.

| Overall (n = 357) | Q (n = 76) | CS (n = 281) | Comparison of Q and CS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) GWG (kg) | 14.0 (8.6) | 15.4 (7.5) | 13.6 (8.9) | t (df = 355) = 1.54, p = .12 |

| Gaining excessive weight, % (n) | 46.5 (166) | 57.9 (44) | 43.4 (122) | Chi square (df = 1) = 5.34, |

| Gaining adequate weight, % (n) | 26.9 (96) | 23.7 (18) | 27.8 (78) | p = .02 |

| Gaining inadequate weight, % (n) | 26.6 (95) | 18.4 (14) | 28.9 (81) |

Abbreviations: CS, continuing smokers; GWG, gestational weight gain; IOM, Institute of Medicine; Q, quitters.

We also evaluated GWG by the duration of smoking abstinence during pregnancy. After adjusting for timing of weight assessment and prepregnancy BMI, women who quit earlier in pregnancy gained significantly more weight (16.9 ± 7.5 kg) than did those who never quit (13.6 ± 8.9), t (347) = 2.23, p = .03. There was no difference in GWG between those who quit later in pregnancy (13.8 ± 7.6) and those who never quit.

Prenatal Smoking Cessation and IOM Guidelines for GWG

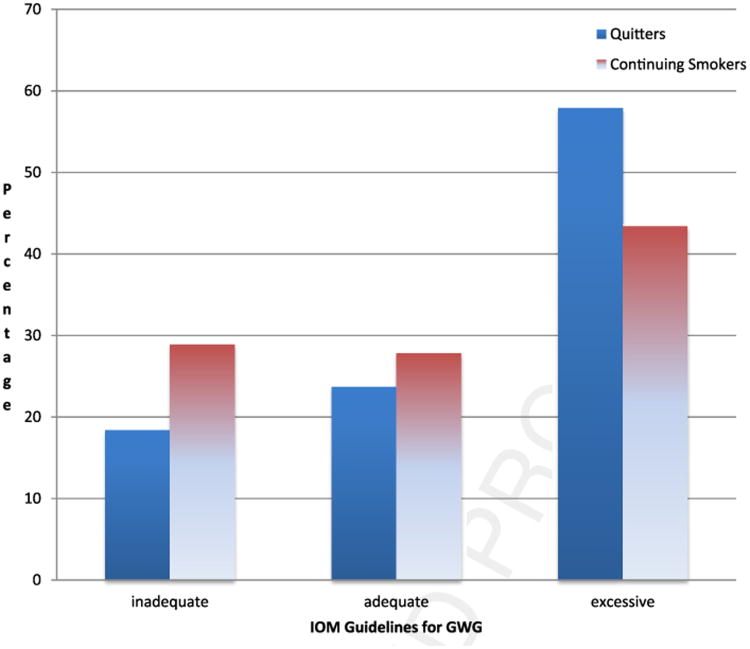

As hypothesized, there was a relationship between smoking cessation and inadequate, adequate, and excessive GWG (chi square = 5.34; p = .02; Table 2). Women who continued to smoke during pregnancy were more likely than those who quit to gain inadequate GWG. Similarly, those who quit smoking during pregnancy were more likely to gain adequate or excessive weight than were those who continued smoking. Specifically, 57.9% of women who quit smoking had excessive GWG, whereas 28.9% of those who continued to smoke gained had inadequate GWG (Figure 1). The effect of cessation on the IOM weight categories remained significant after adjusting for prepregnancy BMI and time between assessment and delivery (chi square = 4.38; p = .04).

Figure 1.

Weight gain according to IOM guidelines by smoking status.

Discussion

Main Findings

Quitting smoking and gaining an adequate amount of weight during pregnancy are important behavioral health goals for pregnant women. Given that smoking cessation is associated with weight gain, prenatal smoking cessation may increase a woman's risk of excessive GWG. Thus, understanding the relationship between weight gain and prenatal smoking cessation is important, particularly among women at risk for poor pregnancy outcomes. The current data from a sample of lower income women enrolled in a community-based prenatal cessation intervention suggest that women who continue to smoke are at risk for inadequate GWG. In contrast, women who quit smoking during pregnancy are more likely to gain either adequate or excessive gestational weight, regardless of the time between weight assessment and delivery or prepregnancy BMI than are continuing smokers.

The link between excessive GWG and smoking cessation using the 1990 IOM guidelines (Adegboye et al., 2010) has been reported previously. However, the present results are the first to examine GWG using the revised 2009 GWG guidelines. Results indicate that more than half of women who quit smoking during pregnancy exceed GWG guidelines. Specifically, 58% of women who quit smoking had excessive GWG. In contrast, 29% of women who continued to smoke during pregnancy gained less than the recommended amount of gestational weight. Thus, smoking increases the risk of inadequate GWG and quitting is associated with either adequate or excessive weight gain.

Strengths and Limitations

Although these data document a relationship between prenatal smoking cessation and GWG, there are several limitations to this study. First, all of the pregnant women participating were enrolled in a clinical program designed to encourage or sustain prenatal smoking cessation. Thus, the women in this trial who quit may not be representative of pregnant smokers who quit without smoking cessation programs. However, given that the majority of smokers who quit as a result of pregnancy do so without intervention (Fingerhut, Kleinman, & Kendrick, 1990; Quinn, Mullen, & Ershoff, 1991), these data provide important information about women for whom quitting may be most difficult. Second, the data presented are derived from a subset of women enrolled in the larger clinical service project, and thus we are unable to compare information on GWG from women without weight to those on whom data are available. Finally, there are limitations to the use of self-reported weight data. Although the use of self-report for pregravid weights is common in research on GWG (Gunderson, Abrams, & Selvin, 2000; Rosenberg et al., 2003), pregravid weight in this study was collected at various points in pregnancy, and the timing may have increased the inaccuracy of women's recall.

Implications for Practice and Policy

These data are the first to document rates of inadequate and excessive GWG using the current IOM guidelines. The findings verify that continuing to smoke during pregnancy is associated with inadequate GWG, which is directly related to infant birth weight and health (Davis & Hofferth, 2012; Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009). Thus, continued efforts to promote prenatal smoking cessation are crucial, and this study confirms the need for additional research on the role of other health behaviors that may be linked with continued prenatal smoking. For example, given the strong link between mood and smoking generally (Niaura et al., 2001), and with prenatal smoking specifically (Zhu & Valbo, 2002), as well as the association of depression and inadequate GWG (Bodnar, Wisner, Moses-Kolko, Sit, & Hanusa, 2009), research on comprehensive behavioral health programs that address mood, smoking, and weight behaviors is needed.

The current data also indicate that women who quit smoking during pregnancy, particularly women who quit earlier, may be at risk for excessive GWG. Similarly, if these findings are confirmed in other samples, the results suggest that women may benefit from programs that target both smoking cessation and weight management to maximize the health benefits of smoking cessation for mothers and infants. Given the well-established risks of smoking during pregnancy for mothers and infants (Bernstein et al., 2005; Butler et al., 1972), the benefits to maternal and neonatal health associated with prenatal smoking cessation clearly outweigh the potential risks of excessive GWG.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the dedication of Patricia Gonzalez, MS, in providing cessation counseling to women, and for her assistance with weight data collection in her position with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Support for the cessation program that recruited participants was provided by Tobacco Free Allegheny, Pennsylvania Department of Health, UPMC Health Plan, and the FISA Foundation. Support for the data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation was provided by R01DA021608 (Levine). These agencies had no additional role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation for this study or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Adegboye AR, Rossner S, Neovius M, Lourenco PM, Linne Y. Relationships between prenatal smoking cessation, gestational weight gain and maternal lifestyle characteristics. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2010;23(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IM, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Solomon L, Heil SH, Higgins ST. Maternal smoking and its association with birth weight. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(5):986–991. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000182580.78402.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler NR, Goldstein H, Ross EM. Cigarette smoking in pregnancy: Its influence on birth weight and perinatal mortality. British Medical Journal. 1972;2:127–130. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5806.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar LM, Wisner KL, Moses-Kolko E, Sit DK, Hanusa BH. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the likelihood of major depressive disorder during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1290–1296. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedergren M. Effects of gestational weight gain and body mass index on obstetric outcome in Sweden. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2006;93(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedergren MI. Optimal gestational weight gain for body mass index categories. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110(4):759–764. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000279450.85198.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RR, Hofferth SL. The association between inadequate gestational weight gain and infant mortality among U.S. infants born in 2002. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;16(1):119–124. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0713-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto AL, Duncan BB, Mengue SS, Nucci LB, Barros EF, Kroeff LR, et al. Prenatal weight gain following smoking cessation. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2007;135(2):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(5):541–544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Fox BJ, Goldstein MG, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(24):3244–3254. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Bennett G, Benowitz NL, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update - A US Public Health Service report. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;35(2):158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Mongoven M, Burau K. Prenatal weight gain patterns and infant birthweight associated with maternal smoking. Birth. 1997;24(4):234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1997.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EP, Abrams B, Selvin S. The relative importance of gestational gain and maternal characteristics associated with the risk of becoming overweight after pregnancy. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2000;24(12):1660–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon KS, Gritz ER, Clayton S, Nisenbaum R. Eating orientation, postcessation weight gain, and continued abstinence among female smokers receiving an unsolicited smoking cessation intervention. Health Psychology. 1999;18(1):29–36. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick JS, Zahniser SC, Miller N, Salas N, Stine J, Gargiullo PM, et al. Integrating smoking cessation into routine public prenatal care: The Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy project. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(2):217–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesges RC, Winders SE, Meyers AW, Eck LH, Ward KD, Hultquist CM, et al. How much weight gain occurs following smoking cessation? A comparison of weight gain using both continuous and point prevalence abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(2):286–291. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linne Y, Dye L, Barkeling B, Rossner S. Long-term weight development in women: A 15-year follow-up of the effects of pregnancy. Obesity Research. 2004;12(7):1166–1178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;3:CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, et al. Births: Final data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007;56(6):1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongoven M, Dolan-Mullen P, Groff JY, Nicol L, Burau K. Weight gain associated with prenatal smoking cessation in white, non-Hispanic women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;174(1 Pt 1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Britt DM, Shadel WG, Goldstein M, Abrams D, Brown R. Symptoms of depression and survival experience among three samples of smokers trying to quit. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(1):13–17. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Frazier AL, Gillman MW. Maternal gestational weight gain and offspring weight in adolescence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112(5):999–1006. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818a5d50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, D'Amico D, Miller A, Broge M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce weight concerns improves smoking cessation outcome in weight-concerned women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:604–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn VP, Mullen PD, Ershoff DH. Women who stop smoking spontaneously prior to prenatal care and predictors of relapse before delivery. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16(1-2):29–40. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90037-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Yaktine A. Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Kumanyika SK, Adams-Campbell LL. A prospective study of the effect of child-bearing on weight gain in African-American women. Obesity Research. 2003;11(12):1526–1535. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schack-Nielsen L, Michaelsen KF, Gamborg M, Mortensen EL, Sorensen TI. Gestational weight gain in relation to offspring body mass index and obesity from infancy through adulthood. International Journal of Obesity. 2010;34(1):67–74. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Subcommittee on Biochemical, & Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4(4):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suellentrop K, Morrow B, Williams L, D'Angelo D. Monitoring progress toward achieving Maternal and Infant Healthy People 2010 objectives-19 states, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2000-2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 2006;55(9):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Skelly J, Bernstein IM, et al. Examining maternal weight gain during contingency-management treatment for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114(1):73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DF, Maddans J, Anda RF, Kleinman JC, Giovino GA, Byers T. Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(11):739–745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, Smith-Yoder D, Artz L, Crawford M, et al. Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavioral impact and cost benefit. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(2):201–206. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrotniak BH, Shults J, Butts S, Stettler N. Gestational weight gain and risk of overweight in the offspring at age 7 y in a multicenter, multiethnic cohort study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(6):1818–1824. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Valbo A. Depression and smoking during pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(4):649–658. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]