Abstract

Amyloid deposits are a hallmark of many diseases. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease a turn between 21Ala and 30Ala, stabilized by a salt bridge between 22Glu/23Asp and 28Lys, may nucleate folding and aggregation of the Aβ peptide. In the present paper we test this hypothesis by studying how salt bridge and turn formation vary with intrinsic and environmental changes, and how these changes effect folding and aggregation of the Aβ peptide.

Keywords: amyloid formation, aggregation, computer simulation

1 Introduction

A signature of Alzheimer’s disease is deposition of the 40–42 residue amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in brain tissue and blood vessels. Most common is Aβ40, while Aβ42 is the more fibrillogenic form, and thus more associated with the disease. The rather large differences in kinetics and stability [1], resulting from the additional C-terminal residues 41Ile and 42Ala, indicate a fragile equilibrium of forces that govern the folding and thermodynamics of the Alzheimer’s peptide. These interactions can be divided in two groups. The first one contains intrinsic forces resulting from the interaction between the residues. The second group encompasses the interaction between the peptide and the surrounding water, membrane, or other peptides.

Intrinsic forces are probed readily by comparing the wild type with various mutations, and a number of point mutations leading to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease document the importance of these forces for folding and stability. Examples are the flemish(21Ala → Gly) and arctic(22Glu → Gly) mutations [2, 3]. The first one leads to increased solubility and decreased fibrillogenesis rates, while the arctic mutation raises the propensity of fibril and protofibril formation [4]. Both mutations have been studied previously by various groups [5–8].

One way to explore the effect of the environment is by comparing solvated peptides with such in a membrane environment. NMR structures of Aβ40 in a membrane-mimicking environment, SDS micelles [9] and 40% triofluoroethanol [10], have large α-helical content. On the other hand, circular dichroism of aqueous Aβ40 indicates a mixture of coil, β-turn, β-sheet and α-helical segments (in order of highest to lowest abundance) [11], and high β-sheet content at air- water [11] or membrane interfaces [12]. The peptide has been also simulated in an implicit membrane environment [13], while Xu et al. probed it in an explicit lipid bilayer composed of DPPC [14].

As a step toward understanding oligomerization of Aβ peptides, we have simulated recently the folding of solvated Aβ39 and Aβ40 monomers, and their dimerization [15, 16]. We identified as key-part the segment 21Ala–30Ala. Turn formation in this segment appears to nucleate monomer folding into a strand-loop-strand -like form, stabilized by long-range electrostatic interactions between 28Lys and either 22Glu or 23Asp [17]. Our results indicate that the dimer is most stable when either the two N-terminal or the two C-terminal are parallel, allowing the formation of contacts between hydrophobic segments, especially the segment 17Leu-18Val-19Phe-20Phe-21Ala. Unlike in the monomer, the salt bridge is formed between two chains, with the formation of the turn and the salt bridge a driving force for oligomerization [16, 18–21].

We expect that the effects of mutations and/or environmental changes are mainly through stabilization or destabilization of this turn. In the arctic mutation the substitution 22Glu to 22Gly is in the turn (22Glu-28Lys) itself, while the Ala21Gly (flemish) substitution is outside that turn, and likely effects its stability differently. The contributions of both residues to the electrostatic stabilization of the 23Asp-28Lys contact is supported by the NMR data [22]. These electrostatic interactions will also change when going from water to a membrane, i.e. an environment with a dielectric constant of ε ≈ 2 – 4 instead of the ε ≈ 80 in water, and may lead to the structural differences between membrane-bound and solvated Aβ-peptides.

In the present article we test this hypothesis through replica exchange molecular dynamics simulations of the Aβ40 wild type, flemish and arctic mutants. Folding pathway, structure and stability, especially of the extended turn region compromised by residues 21Ala to 30Ala, are probed for all three variants. Computational studies in similar spirit include Ref. [23–25]. Folding and dimerization of the wild-type are further compared between solvated molecules and such in gas phase (ε = 1). The later is taken as a crude approximation of a membrane while the peptide-solvent interactions are approximated by an implicit solvent model. Unlike earlier work, our results rely not on a coarse-grained representation of the protein [5] but on a physics-based all-atom model. For a discussion on the relative merits of both representations, see, for instance, Ref. [26].

Our results indicate that the turn region around residue 21Ala-30Ala exists in gas phase with higher frequency than in solution. The increased stability of the turn structure is due to the stronger salt bridge resulting from the lower dielectric constant. This suggests that a membrane environment furthers aggregation and fibril formation. For the mutants we observed that substitutions of Gly for either 21Ala or 22Glu increase local conformational flexibility by lowering the electrostatic interaction between 23Asp-28Lys. The effect is stronger for the arctic than for the flemish mutant suggesting that the loss of charge (by substituting the neutral Gly for 22Glu) adds to conformational flexibility. However, albeit only a salt bridge between 23Asp and 28Lys can be formed in the arctic mutant (22Glu → 21Gly), the turn is due to newly-formed hydrogen bonds as stable as in the wild type, and appears with even higher frequency. The increased flexibility from the weaker salt bridge raises the tendency for beta-sheet formation (albeit not observed for the monomer but only upon dimerization) leading to the increase aggregation rates observed in experiments. On the other hand, the larger flexibility and the loss of salt bridge destabilizes in the flemish mutant (21Ala → 21 Gly) the 21Ala-30Ala turn, and decreases the probability for strand-loop-strand configurations that are parallel aligned. This explains the reduced aggregation and fibrilization rates for this mutant. Together, our results confirm the importance of the 21Ala-30Ala turn for folding and aggregation of Aβ, and adds to the increasing evidence that this turn and its stabilizing interactions should be the premier target for inhibiting amyloid fibrils.

2 Methods

The peptide Aβ40 consists of 40 amino-acid residues, and is generated initially as a linear conformation by the LEAP program, without a blocking group at N-terminal or C-terminal. In the flemish mutant, residue 21Ala is replaced by Gly, and correspondingly 22Glu by Gly in the arctic mutant. All simulations are carried out with the AMBER 9.0 (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement) [27] package using the all-atom force field ff99 [28]. For the solvated peptide the interaction between the peptides and surrounding water are approximated by a generalized Born solvent-accessible surface area (GB/SA) [29] implicit solvent model (Bond radii 0.09Å, solvent dielectric constant 78.5, surface tension 0.005 kcal/molÅ−2). This approximation is necessary to ensure convergence of simulations at acceptable computational costs but has to be taken into account in the analysis of our results. For instance, this approximation obviously ignores dependency of conformational equilibria on pH and salt concentrations.

In the dimer simulations both chains are constructed using again the LEAP module from AMBER9, and then arrange in parallel with the N-terminals aligned. We confine the two molecules to a sphere of given radius through adding an attracting harmonic force. In this way, we avoid states where the separation between the two molecules is too large. Such confinement is justified as it models the rather crowed environment in a cell. In our study, the harmonic constraint is k(r − r0)2/2 when the distance between the center of mass of two Aβ molecules exceeded 20Å, and zero for shorter distances. Here, r is the distance between the center of mass of two molecules, k = 200 kcal/(molÅ2) is a force constant, and the value of r0 is set to 20Å.We define the two centers of mass, COM1 and COM2, by the backbone atoms N:C:CA of the respective chain.

The LEAP generated structures are allowed to collapse to a compact coiled structure in 5,000 steps of steepest decent minimization, before heated over 200 ps to the desired temperature. We use a direct space cut off radius of 16 Å. Temperatures are maintained by a combination of velocity reassignment from Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 5 ps−1. The SHAKE algorithm constraints all bond lengths to their equilibrium distances [30] and maintains the non-bonded cut-off distance at 16Å.

Replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) [31–34] is used to study the thermodynamics of the molecules. Its basic idea is to simulate copies of the system at different temperatures values, each evolving independently by molecular dynamics. Every tswap, replicas i, j at neighboring temperatures Ti and Tj are swapped with a probability

| (1) |

where E is the potential energy of the system. After a successful swap, the velocities are re-scaled according to the new temperatures. Associated with the so generated random walk in temperature it is one in energy allowing the replica to escape local minima. Hence, sampling becomes more efficient than putting all computing resources in a simulation at the lowest temperature [33, 34].

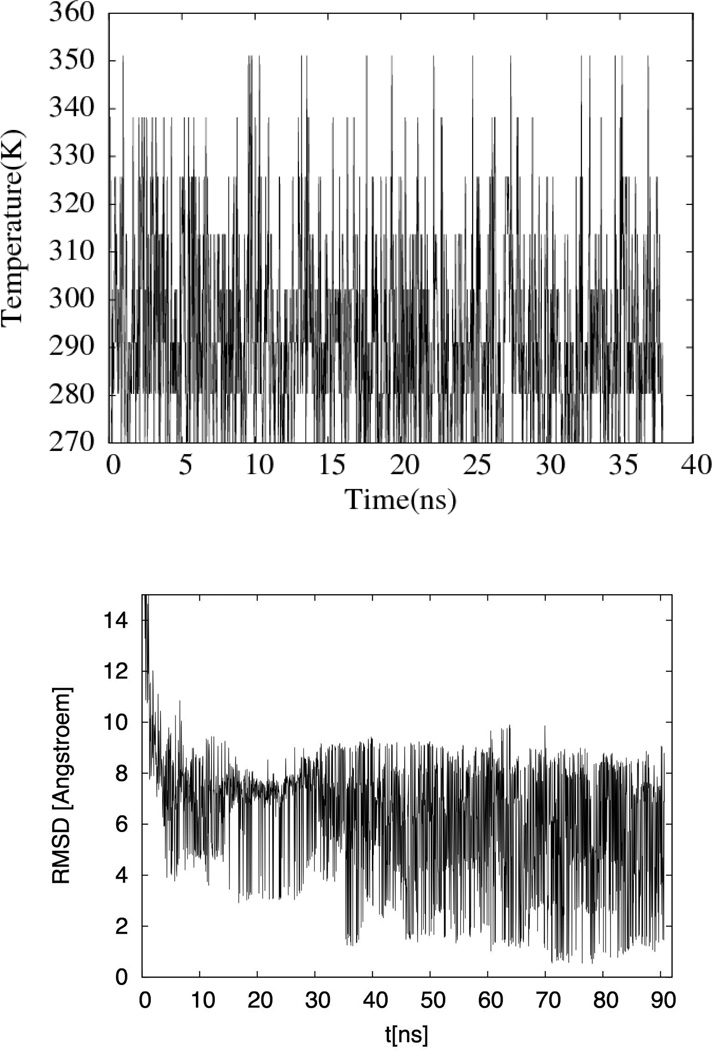

In our case, 8 replicas are distributed over a temperature range of 270K to 350K for the gas-phase simulations, with the temperatures 270K, 280K, 291K, 302K, 313K, 325K, 338K, 351K) determined according to Ref. [35]. For the solvated molecules 16 replicas were used at temperatures 250K, 260K, 270K, 280K, 291K, 302K, 313K, 325K, 338K, 351K, 364K, 378K, 392K, 407K, 423K, 439K. The simulations are done using the sander.MPI module from AMBER9. A swap time tswap of 0.02 ns is chosen, and the length of the simulation for each replica is 160ns in gas-phase, and 90ns for the solvated molecules. The resulting random walk in temperature, associated with structural changes and leading to the improved sampling of low-energy configurations, is illustrated for one replica of the arctic mutant in Fig. 1. As a replica walks toward high temperatures, it can leave local minima and continue to explore the energy landscape. Returning to low temperatures, it therefore may find another local minimum. The associated structures are clustered by by us as described below. The replica exchange molecular dynamics simulations are complemented by three regular canonical molecular dynamics simulations of same length (160ns in gas-phase, and 90ns for the solvated molecules) at temperature 302 K, each starting from a separately generated initial configuration. Our simulation of the monomer in implicit solvent takes about 3.5hr per nanosecond when distributed over 16processors of the NICOLE Linux cluster in Jülich, Germany.

Fig. 1.

(a) Time series of temperature exchange for one of the replica in an implicit solvent simulation of the arctic mutant. In order to keep the figure readable, we show only the first 40 ns of the 90 ns long trajectory. (b) The resulting times series of the root-mean square deviation (rmsd) at T =302K. Reference structure is the one of Fig. 5b.

For both constant temperature and replica exchange molecular dynamics, the initial 5ns nanoseconds are discarded and only the latter 155ns (in gas phase), and 85ns in the implicit solvent, are analyzed. All collected configurations are grouped according to their geometry by evaluating the root mean square deviation (RMSD) over backbone atoms between configurations using the MMTSB toolkit [36]. A cluster is defined by the condition that its members have at most a rmsd of 5Å to the centroid. Only clusters containing more than 10 members are further analyzed. Calculations of molecular properties rely on all snapshot structures. Most of our analysis focuses on T = 302K.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Environment induced changes on Aβ peptides

In order to study how the surrounding environment interacts with the Aβ peptide, we have compared simulations of the peptide in an implicit solvent with such in gas phase. Gas phase simulations of Aβ peptides have been used also by the Shea and Baumketner group [7, 37] to complement and interpret ion mobility spectra, allowing them to determine the size of Aβ oligomers with high precision.

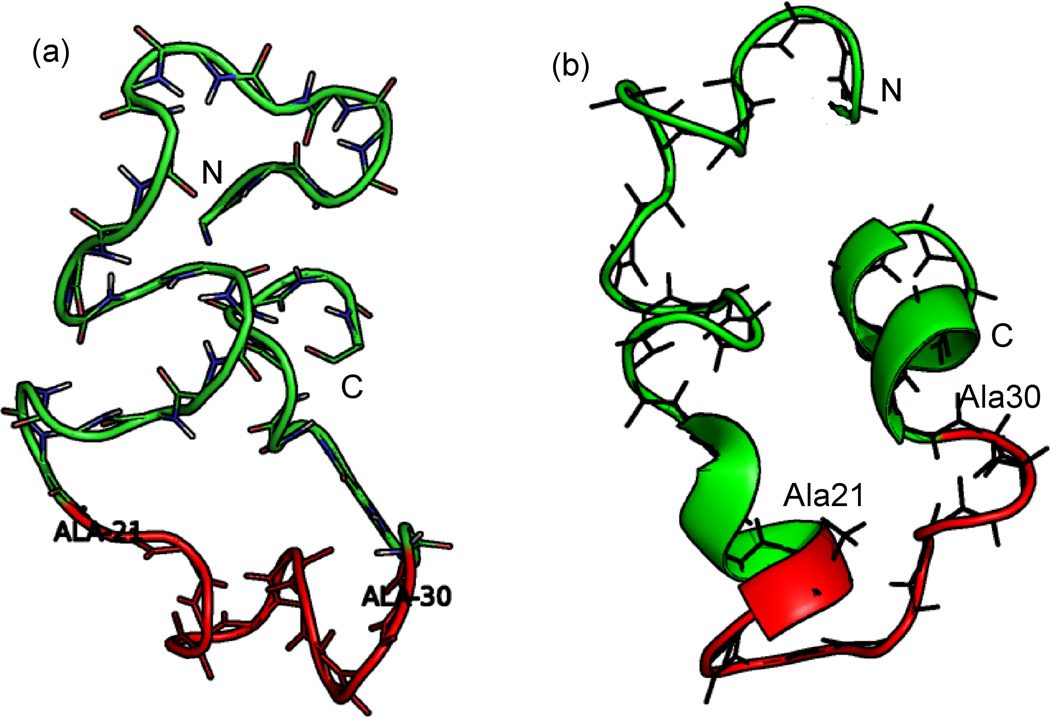

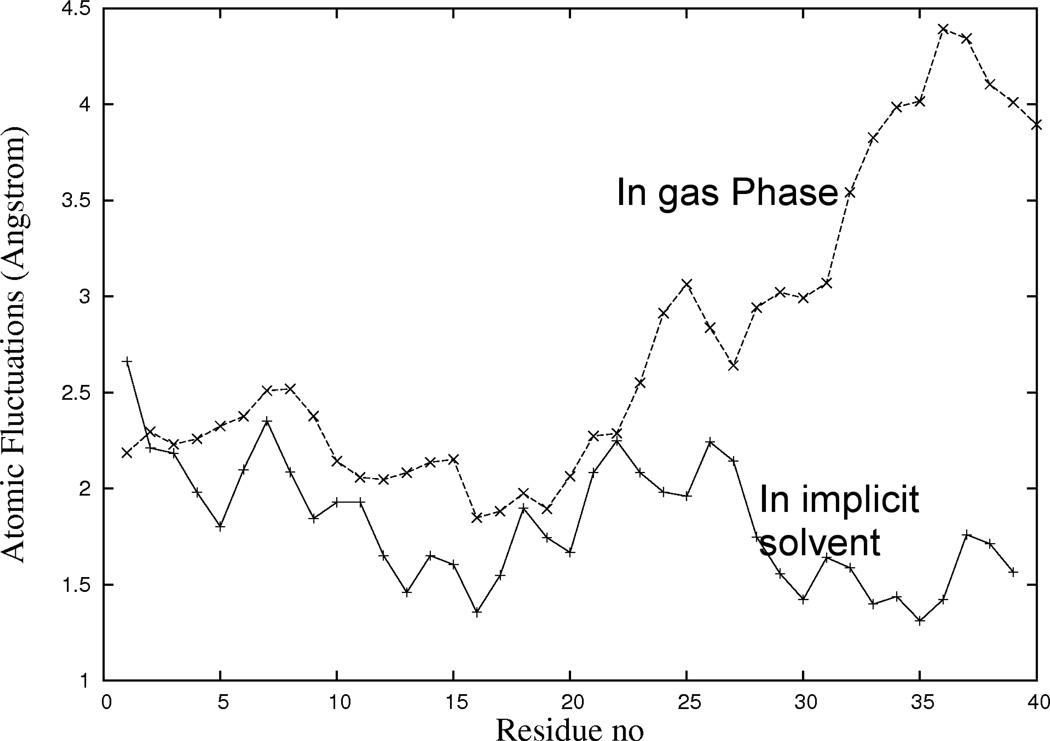

The representatives of low-energy configurations in Fig. 2, taken from gas phase simulations at T = 302K, corresponding to the highest populated cluster, resemble the ones found earlier by us in implicit solvent simulations at similar temperatures. The fluctuations of backbone atoms position in both gas-phase and implicit solvent configurations, shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the region 17Leu - 22Glu is the most rigid region while the C-terminal is most flexible. The qualitative similarity between gas-phase and solvated structures is consistent with results from mass spectroscopy [38, 39] which have shown that under suitable experimental conditions protein structures in the gas phase are close to the hydrated one [40].

Fig. 2.

Monomer configurations representative for the highest populated cluster found at T = 302 K in replica exchange simulations in (a) gas phase and (b) implicit solvent. The two clusters correspond to 58% of configurations in the case of implicit solvent simulation, and 30% for the gas phase simulations. However, in gas phase almost 100% of configurations have the characteristic turn segment 21Ala - 30Ala colored here in red.

Fig. 3.

Fluctuations of positions of atoms in the Aβ-chain (with respect to the lowest-energy configuration) in (a) gas phase and (b) implicit solvent.

We find that at T = 302 K the radii of gyration ranges from 9Å to 10.5Å, not exceeding 11Å, and match the experimental values of Shea et al [7]. Our configurations are more compact than in an implicit solvent where we have found earlier radii of gyration in a range of 9Å to 13Å, again comparable to experimental values. This agreement for both solvated and gas-phase gives confidence in our further analysis. The solvent-accessible surface in the gas phase (2733Å2) is significantly smaller than that of the solvated structures (≈ 3210Å2). The turn around residue 21Ala-30Ala appears in all gas phase configurations, while it is found for the solvated peptide in only about 58% of configurations. An additional second turn around residue 12Val - 17Leu is present in most configurations, but has been observed in only one cluster in implicit solvent. With the exception of 4–5% of antiparallel sheet in the region 26Ser-35Met no helix or sheet structure is found in the gas phase configurations. Especially, residues 1Asp - 9Gly are always coil-like. This is unlike in implicit solvent where 30–40% of configurations are partially helical. Consequently, the pattern of hydrogen bonds differs. The total number of protein-protein hydrogen bonds is larger in gas phase due to reinforcement of favorable protein-protein contacts in the absence of solvent. This self-solvation of the peptide as suggested by Jarrold [40] leads to a general decrease in the accessibility of polar atoms, changing the ratio of solvent-accessible surface between polar and apolar atoms.

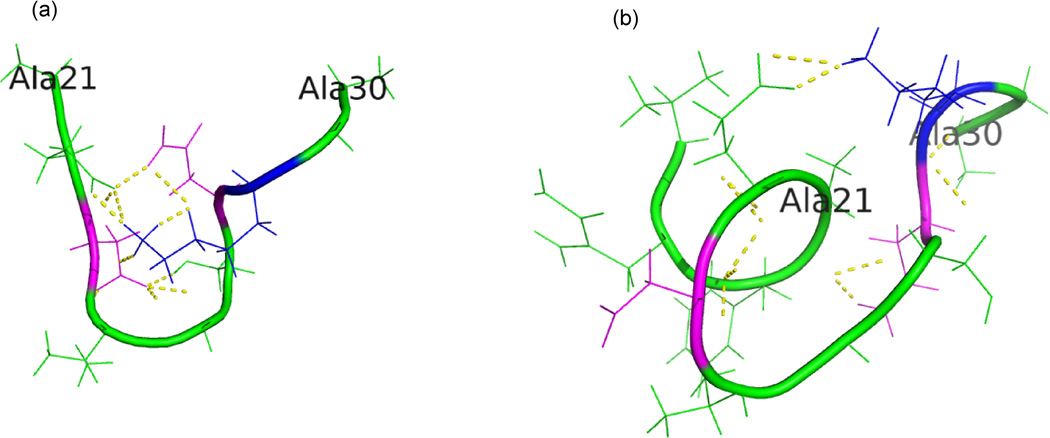

At 302 K, a root mean square displacement based clustering analysis divides all configurations into eight clusters. The eight clusters differ little in their average potential energies. The root mean square deviation of backbone atoms of the turn region 21Ala - 30Ala is ≈ 2:2 Å for two of the three highest populated cluster (together 83% of configurations), and 3.5Å for the third. The difference results from the position of atoms in the residues 22Glu and 23Asp. Depending on the orientation of the associated side chains the number and strengths of the turn-stabilizing salt bridges between 23Asp and 28Lys and 22Glu and 28Lys change. The 28Lys side chain flips from one side of the plane (defined by the turn) to the other decreasing the electrostatic interaction, see also Fig. 4. The stronger electrostatic interaction results in contacts between 22Glu and 27Asn found in about 58% of configurations, while in implicit solvent simulations these contacts are present only in about 15% of configurations. The two possible salt bridges appear in gas phase and implicit solvent with similar frequency: 22Glu - 28Lys (≈ 10 %) and 23Asp - 28Lys (≈ 20%). Hence, our results indicate that the reduced dielectric constant (ε = 1 instead of ε ≈ 80) leads to an additional contact 22Glu-27Asp, resulting in an increased stability of the turn. As a consequence, the monomer is more stable in gas phase than in an implicit solvent, and does not inter-convert on the time scale of our simulations. On the other hand, in water the monomer was found earlier [15] as a mixture of rapidly interconverting conformations, indicating a role for water in driving the soluble conformation.

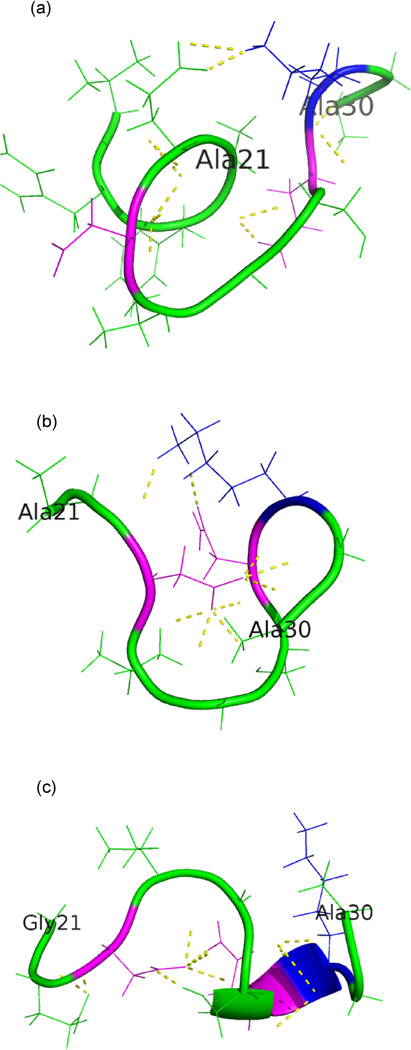

Fig. 4.

Region 21Ala-30Ala of the Aβ40 monomer in the highest populated cluster found at T = 302 K in (a) gas phase and (b) implicit solvent. The residues involved in stabilizing the turn are drawn in magenta or blue. This turn was found in gas phase almost 100% of configurations, but only in 58% of configurations in the solvated system.

The situation is similar for the dimer. Our all-atom simulations started from an extended linear configurations and evolved toward a dimer with parallel N-terminals. Their N-N parallel arrangement is similar to that observed in implicit solvent, and resembles the two strands in a β-sheet facing each other in a plane [16]. The frequency of this configuration is with ≈ 53% comparable to that of solvated molecules (≈ 45%). However, as in the case of the monomer no secondary structure is found. The dominant cluster, compromising ≈ 50% of configurations, is a random coil with turn around 21Ala - 30Ala. This is not unexpected as the 25Gly, 26Ser, and 27Asp residues have a high probability to be within a beta turn. As in the case of the monomer, the position of backbone atoms fluctuate least in the 17Leu - 22Glu region, thus maintaining its rigidity. A similar trend was observed for monomer and dimer in implicit solvent, with minimum fluctuations around the 17Leu - 21Ala region. This observations is consistent with NMR studies [41] which suggest a well-defined and structured central hydrophobic region, 17Leu - 21Ala, as critical for fibril formation [42]. As in the case of the monomer the frequency of salt bridges (22Glu/23Asp - 28Lys) is comparable to that of solvated molecules (15%). However, the additional contact between 22Glu and 27Asn (observed in ≈ 50% of configurations compared to 22% in implicit solvent) suggests that the dimer is more stable than in solution.

Our results indicate that the stronger electrostatic interactions in gas phase, or a membrane environment, strengthen the salt bridges that stabilize the turn made of residues 21Ala-30Ala. As a consequence this turn appears in almost all of the monomer configurations. As this turn is assumed to nucleate folding and aggregation of Aβ, we would expect a higher aggregation rate in a membrane environment than for the solvated protein. However, our results for the peptide in gas phase differ from the measured ones for the molecule in a membrane environment albeit the dielectric constant (ε = 1)in gas phase simulation is close to the ε = 2 – 4 in a membrane environment, and much lower than the ε ≈ 80 in water. A NMR study in membrane mimicking environment (TFE/water mixture) [43] found high helical content that is absent in our gas phase study. In light of these differences one has to take our conclusion of higher aggregation rates in a membrane environment with a grain of salt.

3.2 Mutation-induced changes in the Aβ-peptide

Point mutation allow one to evaluate the delicate equilibrium of forces that govern the formation and stability of the Aβ-peptide. In the present paper we focus on the flemish and arctic mutants, as we are especially interested in the stability of the segment 21Ala – 30Ala. For both mutants, the circular dichroism spectra are consistent with an ensemble of random coil and β-sheet conformations indicating a higher flexibility for both mutations. However, the mutants differ in their solubility and propensity for fibril formation. The arctic mutant, replacing 22Glu by Gly, causes accelerated Aβ aggregation with larger formation of neurotoxic intermediates [44] and Aβ protofibrils in vitro. On the other hand, the flemish mutation (replacing 21Ala by Gly) leads to increased solubility and decreased fibrillogenesis. Because of these opposite effects, the two mutants are especially suitable to study the effect of intramolecular interactions on aggregation and oligomerization.

The solvent-accessible surface of both the arctic (2724Å2) and the flemish mutant (2750Å2) is significantly reduced with respect to the wild type (3050Å2). This differences results from larger exposure of side-chain atoms in the wild type Aβ peptide than in the mutants. The solvent accessibility of the 23Asp, 37Gly residue side chain agrees in mutant and wild type, whereas those of residues 11Asp and 21Gly and 29Gly differ in wild-type and each of the mutants (data not shown). The root mean square fluctuation of backbone atoms indicate that the flemish mutant has a higher flexibility at the N- and C-terminal than the arctic mutant. The radius of gyration is with around 10 Å similar for arctic and flemish mutant, and comparable to the 9 to 13Å of the wild type peptide.

3.2.1 Arctic mutant

Clustering of the conformations sampled by replica exchange molecular dynamics leads for the arctic mutant monomer to ten major cluster that together compromise 95% of all configurations. More than 40% are in the highest populated cluster. The configuration closest to the centroid is shown in Fig. 5. About 70% of all configurations (the eight most populated clusters) have the turn around 21-Ala to 30Ala. In the wild type this turn appears only with 58% frequency. The other two cluster have instead a turn around residue 7Asp - 15Gln. New is the prevalence of right-handed 310-helical structures in the middle region (Gln15 - Gly22), and the disordered N-terminus. Wild type and arctic mutant also differ in the alpha-helix content in the region 18Val - 23Asp. This difference can be attributed due to the substitution of a polar, acidic amino acid by a small, neutral one (Glu22Gly), and is consistent with the NMR chemical shifts [45]. Besides these differences, the highest populated eight clusters are almost identical in backbone structure to that of the wild type, and even the turn around region 21Ala - 30Ala is formed in the first 5ns simulation. The constant temperature simulations suggest also a similar folding pathway for arctic mutant and the wild type. This indicates that mutations at position Glu 22 do not influence the turn structure of Aβ(21ALa - 30Ala) leaving the Aβ folding nucleus unaltered.

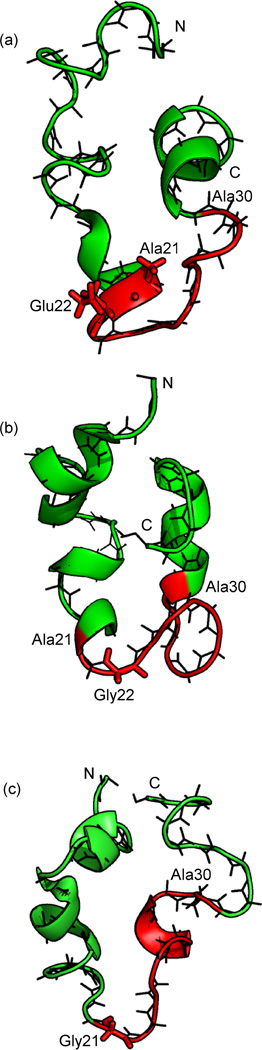

Fig. 5.

Monomer configurations representative for the highest populated cluster found in implicit solvent replica exchange simulations at T = 302 K of (a) the wild type (58% of configurations), (b) the arctic (≈ 40 %) and (c) the flemish mutant (≈ 40 %). The turn segment 21Ala - 30Ala is colored in red.

On first view this is unexpected as the mutation is within the turn, and the salt bridge 22Glu- 28Lys cannot be formed. Naively, one would expect therefore a decreased turn stability. This the more as the salt bridge between 23Asp and 28Lys is observed in only 7% of configurations, and contacts between polar amino acids 23Asp - 27Asn, appear also only with reduced frequency: in 15% vs. 45% of configurations. However, reduced turn stability is not observed in either monomer nor dimer. In the later case, the extended linear configuration of the two arctic mutant chains collapsed to a configuration with parallel N-terminals. A representative conformation belonging to the most populated cluster representing about 40% of configurations and lowest energy for the mutant dimer is shown in Fig. 6. As for the wild type we find the turn around residue 21Ala - 30Ala, indicating that the mutation at 22Glu does not change the turn structure and leaves the Aβ folding nucleus unaltered during oligomerization. This is because the bend motif is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between residue 23Asp Oδ atoms and backbone amide hydrogen atoms that compensate for the missing 22Glu-28Lys salt bridge (see Fig. 7.

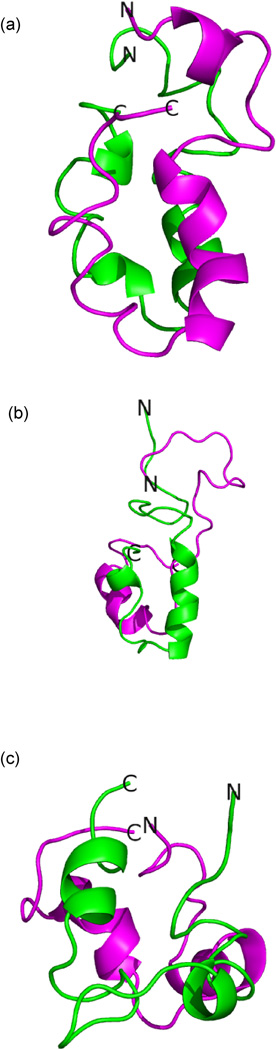

Fig. 6.

Dimer configurations representative for the highest populated cluster found in implicit solvent replica exchange simulations at T = 302 K of (a) the wild type (with a frequency of, ≈ 40 %) (b) the arctic (with a frequency of, ≈ 40 %),and (c) the flemish mutant (with a frequency of,≈ 55 %). The two chains are drawn in different colors.

Fig. 7.

Region 21Ala-30Ala of the Aβ40 monomer in the highest populated cluster found in implicit solvent replica exchange simulations at T = 302 K of (a) the wild type (observed in about 58% of configurations), (b) the arctic (observed in ≈ 70 % of configurations) and (c) the flemish mutant (observed in ≈ 58 % of configurations). The residues involved in stabilizing the turn are drawn in magenta or blue.

The time series of the secondary structure profile shows that intermediate conformations have beta sheet structure around the 10Tyr - 14His and 34Leu - 37Gly region. Such a presence of the beta sheet like structure might increase the conversion from random coil to helix to beta sheet structure in the fibril and raise the aggregation rate of the mutant peptide [46–48]. Note that for the arctic mutant monomer we did not observe this high percentage of beta sheet intermediate. Hence, the presence of the beta sheet structure in the dimer likely results from interactions between the chains.

Despite the missing salt bridge the turn motif remains stable and continues to act as nucleus for folding and aggregation. The characteristic dimer configurations with parallel N-terminals appears with comparable frequency (≈ 40%) as for the wild type. Together with the observed beta-strand formation this enables the mutant to form aggregates more easily leading to earlier formation of protofibrils. This is somehow different from observations by Head Gordon [5] which seem to indicate that the glycine mutation at position 22 increases the flexibility in the turn region of the Aβ monomer allowing the formation of new contacts that stabilize the fibril at the interface.

3.2.2 Flemish mutant

A clustering analysis for the flemish mutant simulations finds at 302K three major clusters compromising together 83% of configurations. The turn around residues 21Gly - 30Ala is seen in only one cluster, and appears with a frequency of 25%, as compared to 58% for the wild type and 40% for the highest-populated cluster as shown in Fig. 5). In the flemish mutant this turn is stabilized only by interactions between the 23Asp side chain with the backbone, and between 24Val and 27Asn, 25Gly. The salt bridge between 28Lys and 22Glu is missing, and the 23Asp - 28Lys salt bridge appears only in 5% of configurations (≈ 20% in wild type). In the other two clusters, which together collect 58% of configurations, the turn is shifted from 21Gly-30Ala towards 16Lys - 23Asp. This is consistent with observations by the Derreumaux group [6] who see a reduction in the β-content in the flemish mutant.

The above result suggests that glycine at position 21 reduces the N-terminal beta strand propensity by shifting the turn region, destroying the supposed folding and aggregation nucleus. For the dimer, the lowest energy configuration (see Fig. 6) is still one with the two N-termini parallel aligned (as in wild type and arctic mutant), and appears in ≈ 55% of configurations. As in the monomer, the turn is shifted from 21Gly - 30Ala to 16Lys-23Asp, see also Fig. 7. As a consequence, one does not find the salt bridges 22Glu - 28Lys and 23Asp - 28Lys that stabilize the folding nucleus in the wild type. Because of this missing turn there is an increased propensity to adopt unstructured conformations that inhibit fibril growth. For instance, in ≈ 23% of configurations the two chains are crossing each other under angles that makes attachment of additional chains unlikely. Our result is consistent with work by Head Gordon [5] which also observed that the glycine mutation at residue 21 disrupts the exterior N-terminal strand regions, thereby degrading order throughout each protofilaments and at the interface between protofilaments.

Note that the helical content is higher in flemish mutant than for the wild type peptide and the arctic mutant dimer. This is in contrast to experimental result, whereas at pH 6 and 7, no helical structure was found. It is also interesting to observe that at pH 6 a high amount of the β-sheet conformation (60%) was observed which is missing in our simulation. Both observations are likely related to the known bias toward helical structures in the present version of Amber.

4 Conclusions

We have performed replica exchange and canonical molecular dynamics simulations of the Aβ (1–40) peptide wild type in gas phase and implicit solvent, and of the flemish and arctic mutants in implicit solvent. These simulations allow us to study the effect of environment (gas phase vs. solvent) and changes in the intramolecular equilibrium of forces (by way of mutations) on folding and aggregation of this peptide. Our results support an earlier conjecture that turn formation of segment 21Ala–30Ala, leading to strand-beta-strand configurations with a tendency to align in parallel on dimer formation, acts as a nucleus for oligomerization. A stabilization of this turn by either a more favorable mixture of internal forces (as in the case of the arctic mutation) or the stronger electrostatic interactions in gas phase (or a membrane environment) will lead to higher aggregation and fibril formation rates. Our results further indicate that the turn formation does not require the salt bridges between 22Glu (or 23 Asp) and 28Lys, which when they exist are stabilizing this turn. Other forces, such as contacts between 24Val and 28Lys, are also important for stabilizing this turn. The turn is therefore an obvious target when searching for ways to inhibit or degrade amyloid fibrils.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by research grant CHE-0809002 of the National Science Foundation (USA) and GM62838 of the National Institutes of Health(USA). All calculations were done on computers of the John von Neumann Institute for Computing, Research Center Jülich, Jülich, Germany.

References

- 1.Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. Nature. 1987;325:733. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy E, Carman MD, Fernandez-Madrid IJ, Power MD, Lieberburg I, van Duinen SG, Bots GT, Luyendijk W, Frangione B. Science. 1990;248:1124. doi: 10.1126/science.2111584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendriks L, Van Duijn CM, Cras P, Cruts M, Hul WV, Harskamp FV, Warren A, McInnis MG, Antonarakis SE, Martin JJ, Hofman A, Broeckhoven CV. Nat. Genet. 1992;1:218. doi: 10.1038/ng0692-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murakami K, Irie K, Morimoto A, Ohigashi H, Shindo M, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Neurotoxicity and physicochemical properties of Aβ mutant peptides from cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawzi NL, Kohlstedt KL, Okabe Y, Head-Gordon T. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94:2007. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huet A, Derreumaux P. Biophysical Journal. 2006;91:3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krone MG, Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Lazo ND, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:221. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam AR, Teplow DB, Stanley HE, Urbanc B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17413. doi: 10.1021/ja804984h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sticht H, Bayer P, Willbold D, Dames S, Hilbich C, Beyreuther K, Frank RW, Rosch P. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;233:293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.293_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schladitz C, Vieira EP, Hermel H, Mohwald H. Biophys. J. 1999;77:3305. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtain CC, Ali F, Volitakis I, Cherny RA, Norton RS, Beyreuther K, Barrow CJ, Masters CL, Bush AI, Barnham KJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mobley DL, Cox DL, Singh RRP, Maddox MW, Longo ML. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3585. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.032342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Shen J, Luo X, Zhu W, Chen K, Ma J, Jang H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501218102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand P, Nandel FS, Hansmann UHE. J. Chem. Phy. 2008;128:165102. doi: 10.1063/1.2907718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand P, Nandel FS, Hansmann UHE. The Alzheimer -amyloid Aβ 139dimer in an implicit solvent. J. Chem. Phy. 2008;129:195102. doi: 10.1063/1.3021062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1581. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melquiond A, Dong X, Mousseau N, Derreumaux P. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:244. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chebaro Y, Mousseau N, Derreumaux P. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:7668. doi: 10.1021/jp900425e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarus B, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:815. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarus B, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16159. doi: 10.1021/ja064872y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant MA, Lazo ND, Lomakin A, Condron MM, Arai H, Yamin G, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705197104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolaos SG, Yan Y, Scott MA, Wang C, Angel EG. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1448. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Ding F, Sammond D, Khare S, Buldyrev SV, Stanley HE, Dokholyan NV. Biophysics. J. 2004;87:2310. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz U, Urbanc B, Borreguero JM, Lazo ND, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2005;102:18258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509276102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheraga HA, Khalili M, Liwo A. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2007;58:57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Merz KM, Pearlman DA, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Wong KF, Paesani F, Wu X, Brozell S, Tsui V, Gohlke H, Yang L, Tan C, Mongan J, Hornak V, Cui G, Beroza P, Mathews DH, Schafmeister C, Ross WS, Kollman PA. AMBER 9. San Francisco: University of California; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:1049. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawkins GD, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:19824. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunsteren WF, Berendsen HJC. Mol. Phys. 1977;34:1311. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hukushima K, Nemoto K. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 1996;65:1604. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geyer CJ. Computing Science and Statistics: Proc. 23rd Symp. Interface; 1991. p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansmann UHE. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;281:140. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nadler W, Hansmann UHE. Phys. Rev. E. 2007;76:065701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.065701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks Ch L., III Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modeling. 2004;22:377. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Protein Science. 2006;3:420. doi: 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Science. 1989;246:64. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharon M, Robinson CV. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.090816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarrold MF. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2000;51:179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou L, Shao H, Zhang Y, Li H, Menon NK, Neuhaus EB, Brewer JM, Byeona IJL, Ray DG, Vitek MP, Iwashita T, Makula RA, Przybyla AB, Zagorski MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1992. doi: 10.1021/ja036813f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraser PE, Nguyen JT, Surewicz WK, Kirschner DA. Biophys. J. 1991;60:1190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stricht H, Bayer P, Willbold D, Dames S, Hilbich C, Beyreuther K, Frank RW, Rosch P. J. Biochem. Tokyo. 1995;233:293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.293_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Biochemistry J. 1992;31:1647. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang WY, Larios E, Gruebele M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:16220. doi: 10.1021/ja0360081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imamura H, Chen JZ. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2006;63:555. doi: 10.1002/prot.20846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei G, Song W, Derreumaux P, Mousseau N. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:5681. doi: 10.2741/3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]