Abstract

Aims To identify clinical factors associated with disability in depressed older adults with bipolar disorder (BPD) receiving lamotrigine.

Methods Secondary analysis of a multi-site, 12-week, open-label, uncontrolled study of addon lamotrigine in 57 adults 60 years and older with BD I or II depression. Measures included the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G), Dementia Rating Scale (DRS), and WHO-Disability Assessment Scale II (WHO-DAS II).

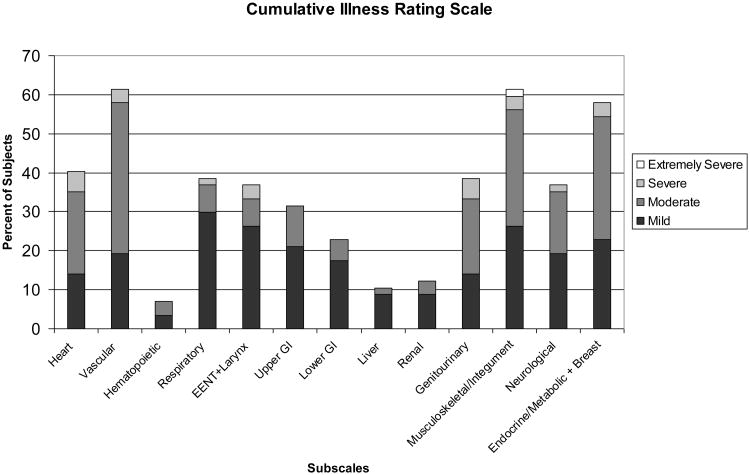

Results Medical comorbidiy in this group of elders was substantial, with roughly 60% of subjects having disorders of the vascular, musculoskeletal/integument, and endodrine/metabolic/breast systems. We found significant relationships among mood (MADRS), medical comorbidity (CIRS-G), cognition (DRS), and disability (WHO-DAS II). More severe BPD depression, more medical comorbidity and more impaired cognition were all associated with lower functioning in BPD elders.

Conclusions Our findings fit the paradigm shift that has been occurring in BPD, supporting the notion that BPD is not solely an illness of mood but that it affects multiple domains impacting overall functioning.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, elderly, geriatric, lamotrigine, mood stabilizer, anticonvulsant, depression

Introduction

In the past several years, in the field of psychiatry there has been a paradigm shift in the understanding of bipolar disorder (BPD). Among researchers, BPD is no longer being seen as a disorder solely of cyclical mood episodes interspersed with normal euthymic periods, but rather as a multi-system disease that is chronic and progressive (1, 2). Numerous studies in the past 10-15 years have shown that across the life-span BPD is associated with increased medical comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, and substantial impairment in everyday function (3-5). Additionally, while suicide contributes to premature mortality in BPD, evidence now reveals that medical comorbidity (cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease) predominantly contributes to excess mortality, ranging from 35% to 2-fold higher than the general population and higher than major depressive disorder (6). Hence, the paradigm shift in understanding extent and severity of the effects of BPD on an individual has led to broadening of treatment to encompass medical comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, and everyday function.

The paradigm shift in BPD is relevant to patients across the lifespan and perhaps most acutely to older adults with BPD where the medical comorbidity and cognitive dysfunction are most pronounced. However, older adults with BPD have been a segment of the population of individuals with BPD that have been least studied with this paradigm shift in mind. The reasons for this include longstanding misconceptions that BPD burns out with age, that patients with BPD do not make it into older age because of premature mortality, and funding priorities of national governments and the pharmaceutical industry (7). There is a growing need to understand the healthcare needs of elders with BPD better because this segment of the population is growing and is among the most expensive utilizers of healthcare (8).

We have previously reported on a multi-site open-label, prospective trial of lamotrigine for geriatric bipolar depression (9). In our previous study of lamotrigine in older people with bipolar depression, lamotrigine was associated with improvements in depression, psychopathology and functional status. In a follow-up analysis of the patients enrolled in the trial, we found that lamotrigine appeared to work well in depressed BPD older adults with high levels of cardiometabolic risk and low levels of mania (10).

To understand the relationships among medical comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, and mood on everyday function better, we carried out secondary analyses of the baseline data collected in our open-label trial of lamotrigine for geriatric BPD depression (9). Our interest was in examining to what extent medical comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction and mood impacted on everyday function and to what extent these domains might be synergistic. While it is well understood that these domains impact on everyday function individually (11), we were interested in exploring whether, when acting together, these domains would have greater than expected impact on an individual with BPD.

Methods

We conducted a multi-site, 12-week, open-label, uncontrolled trial of add-on lamotrigine in 57 adults 60 years and older with BPD I or II depression. Detailed methods of the trial are described elsewhere (9). All subjects met depressive symptom severity criteria of 18 or greater on the GRID version of the 24-item Hamilton Depression Ratings Scale (GRID HAM-D) (12, 13). Individuals with dementia were excluded from the study.

Measures

Mood

We assessed mood with the MADRS (14), GRID HAM-D, and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (15).

Medical Comorbidity

Medical illness burden was evaluated at baseline with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) (16). The CIRS-G organises acute and chronic medical burden across different systems (heart, vascular, etc.), rating burden within each system from “0” (“no problem”) to “4” (“extremely severe/immediate treatment required/severe impairment in function”). Past significant problems that are not currently active are rated as “1.”

Cognition

Cognitive function was assessed with the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) (17). This instrument has demonstrated sensitivity and specificity in elderly individuals, including those with mood disorders (18). It assesses cognitive function in several domains, including attention, executive function (Initiation/Perseveration), visuospatial ability (construction), abstraction (conceptualization), and memory.

General health/disability status was evaluated with the WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II) (19). The WHO-DAS II assesses the following domains of function: understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with others, household and work activities, and participation in society. The WHO-DAS II is cross-cultural and treats all disorders at parity when determining level of function. The following items from the WHO-DAS II that had a cognitive component were aggregated together: Getting around (s1, s7), life activities (s2), understand/ communicates (s3, s6), self-care (s8, s9). These items were used to form a subscale, to focus on everyday function that could be impacted by cognitive impairment.

Statistical Methods

Multiple linear regression models were fitted with WHO-DAS II (or a cognitively-oriented subscale of WHO-DAS II) considered as the outcome measure. Models included adjustment for age and education. A first model considered the full WHO-DAS II scale score, regressed with CIRS-G and MADRS as explanatory variables. This model used all data from 53 subjects. Since the DRS cognitive test data were not collected for all subjects in the sample, this model did not consider DRS.

A second model considered a WHO-DAS II subscale involving the items thought to engage cognitive functioning as measured by DRS. As explanatory variables, we also considered subscales of DRS, specifically those associated with I/P and memory. This allowed for the association of everyday function as measured by the WHO-DAS II items with specific cognitive domains. This second analysis involved 29 subjects.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the subjects (n=57) have been reported previously. In brief, subjects were mean (SD; range) age of 66.5 years (6.7; 60-90), 40% female, 86% Caucasian, mean education of 14.5 years (2.7; 8-23), 77.2% bipolar I and 22.8% bipolar II. Mean CIRS-G was 9.5 (4.7; 2-21), which is consistent with medical severity noted in geriatric samples in mood disorder treatment studies (16). As illustrated in Figure 1, medical comorbidiy in this group of elders was substantial, with roughly 60% of the subjects endorsing disorders of the vascular, musculoskeletal/integument, and endodrine/metabolic/breast systems. Individuals were moderately depressed with a mean (SD) MADRS score of 25.3 (8.3) and moderately functionally impaired with a WHO-DAS II subscale scores: Getting around=5.1 (3.0), Self-care=3.5 (2.0), Life activities=2.9 (1.2), Understand/communicate=4.7 (1.9), Participation in society=6.0 (2.0), and Getting Along with people=4.1 (2.1). Married subjects comprised 45% (n=26) of the group, while 45% (n=26) were living alone. Among those with DRS data, there were little differences with the sample as a whole. For instance, for this subgroup, mean (SD; range) age was 66.4 years (6.4; 60-85) and mean (SD; range) education of 14.9 years (2.8; 8-21).

Figure 1. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRS-G) scores in 57 older adults with bipolar disorder.

We found significant relationships between everyday function (WHO-DAS II) and medical comorbidity (CIRS-G), cognitive function (DRS memory), and mood (MADRS). See Tables 1 and 2. In the model, a 10 point increase on the MADRS resulted in a 2.3 point increase in the WHO-DAS II, while a 10 point increase in CIRS-G resulted in an 8.1 increase in the WHO-DAS II. We found no interactive (synergistic) effects among the domains on everyday function.

Table 1. Parameter estimates for the regression model incorporating medical burden (CIRS-G) and depression (MADRS) scores on everyday function (WHO-DAS II) among 53 older adults with bipolar disorder.

| β | Std. Error | t | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval (β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 30.726 | 12.147 | 2.530 | .015 | 6.303 | 55.149 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRS-G) | .808 | .206 | 3.921 | <.001 | .394 | 1.223 |

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) | .230 | .109 | 2.111 | .040 | .011 | .450 |

| Education | -1.033 | .333 | -3.103 | .003 | -1.703 | -.364 |

| Age | .001 | .134 | .011 | .992 | -.267 | .270 |

Table 2. Parameter estimates for the regression model incorporating cognition (DRS I/P and DRS Memory) and medical burden (CIRS-G) Scores on everyday function (WHO-DAS II cognitively-oriented subscale) among 29 older adults with bipolar disorder.

| β | Std. Error | t | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval (β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 75.658 | 17.949 | 4.215 | <.001 | 38.528 | 112.788 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRS-G) | .490 | .223 | 2.198 | .038 | .029 | .951 |

| DRS Initiation/Perseveration Subscale | -.097 | .209 | -.461 | .649 | -.529 | .336 |

| DRS Memory Subscale | -2.014 | .664 | -3.035 | .006 | -3.388 | -.641 |

| Education | -.531 | .282 | -1.886 | .072 | -1.114 | .051 |

| Age | -.054 | .108 | -.504 | .619 | -.277 | .168 |

There was little discrepancy in age and education between those with DRS data versus those without. For the second model, MADRS was initially included in this model, but was found not to be significant and subsequently removed. R-square and adjusted R-square for the first model were: 0.382, 0.330; for the second model the values were 0.577, 0.507 (the difference in the R-squares suggests that cognition can help explain variability in certain items of the WHO-DAS II).

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the baseline data acquired in an open-label trial of lamotrigine for BPD depression, we found significant relationships between everyday function and medical comorbidity, cognitive function, and mood. More severe BPD depression, more medical comorbidity and more impaired cognition were all associated with lower functioning in BPD elders. A recent review of the literature on comorbidity in older adults with BPD comorbidity concluded that medical comorbidity is common, affecting multiple organ systems with a mean of 3-4 medical conditions (20). The most frequently seen comorbidities in this sample were disorders of the vascular, musculoskeletal, and endrocrine/metabolic systems. It appears that the relationships between BPD and medical illnesses are multifactorial, related to shared genetic risk, iatrogenic medication effects, lifestyle and other factors (21-24). With some medical conditions, such as diabetes, there may be a bidirectional relationship between psychiatric and medical illnesses (23, 25).

We found no greater than expected impairment in everyday function among BPD individuals when these domains were looked at together. It appears that multiple factors and not one particular factor impacts functional outcomes. Our findings support the notion that BPD is not solely an illness of mood, but that it affects multiple domains impacting patients overall functioning (1, 2).

While our findings fit the paradigm shift that has been occurring in BPD, some limitations of the findings need to be considered. First, the WHO-DAS II is a self-report and has been criticized for failing to identify relationships between observed cognitive dysfunction and identified functional impairments in schizophrenia (4). Hence, the measure is subject to bias and may underreport deficits in everyday function. Second, the sample studied is a sample of convenience and is biased to patients eligible and willing to undergo a trial of lamotrigine. By design, individuals with dementia were excluded from our study. Consequently, the patients reported may not reflect the larger pool of older adults with BPD. Last, the small sample size resulted in limited power to look at interaction effects among the domains.

Noting the above limitations, our analysis supports the understanding that BPD impacts an individual beyond mood and that treatments need to be directed to address all aspects of the illness for patients to enjoy full and sustained recovery. Our findings emphasize the need to look beyond BPD symptoms in assessment and treatment planning. Given the significant presence of medical and cognitive comorbidities among BPD elders, it is critical that clinicians providing care to these individuals carefully assess for concurrent conditions, use treatments that do not worsen these comorbidities, and coordinate care with other providers to minimize treatment burden and avoid conflicting information or advice (20). Considering the global demographic trends in community and healthcare settings, clinicians in both primary and specialty care will be likely to see and need to provide services to geriatric patients with mood disorders (26, 27). Integrated care that addresses medical illness, mood and cognitive function together are needed to optimize health outcomes for this vulnerable group of patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an investigator-initiated research grant from GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA, and grant UL1RR024989 from Case Western Reserve University Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA). The CTSA is a component of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center for Research Resources or the NIH.

Contributor Information

Ariel Gildengers, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic

Curtis Tatsuoka, Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Christopher Bialko, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Kristin A. Cassidy, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Philipp Dines, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

James Emanuel, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic

Rayan K. Al Jurdi, Mental Health Care Line, Michael E. DeBakey, VA medical Center, Baylor College of Medicine

Laszlo Gyulai, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center and School of Medicine

Benoit H. Mulsant, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto

Robert C. Young, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

Martha Sajatovic, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

References

- 1.Leboyer M, et al. Can bipolar disorder be viewed as a multi-system inflammatory disease? Journal of Affective Disorders. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.049. In Press (0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leboyer M, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar disorder: new perspectives in health care and prevention. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1689–95. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06347yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wingo AP, et al. Factors associated with functional recovery in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(3):319–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey PD, et al. Cognition and disability in bipolar disorder: lessons from schizophrenia research. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):364–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1561–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. see comment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W. Premature mortality from general medical illnesses among persons with bipolar disorder: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):147–56. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sajatovic M, Blow FC. Bipolar Disorder in Later Life. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilbourne AM. The burden of general medical conditions in patients with bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(6):471–7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajatovic M, et al. Multisite, open-label, prospective trial of lamotrigine for geriatric bipolar depression: a preliminary report. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(3):294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gildengers A, et al. Correlates of treatment response in depressed older adults with bipolar disorder. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(1):37–42. doi: 10.1177/0891988712436685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowie CR, et al. Prediction of real-world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(9):1116–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JB, et al. The GRID-HAMD: standardization of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(3):120–9. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f948f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery S, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young RC, et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133(5):429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MD, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Research. 1992;41(3):237–48. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajji TK, et al. The MMSE is not an adequate screening cognitive instrument in studies of late-life depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43(4):464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epping-Jordan JA, Ustun TB. The WHODAS-II: level the playing field fo all disorders. Bull WHO. 2000;(6):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lala SV, Sajatovic M. Medical and psychiatric comorbidities among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder: a literature review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(1):20–5. doi: 10.1177/0891988712436683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151489.36347.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunes PV, Forlenza OV, Gattaz WF. Lithium and risk for Alzheimer's disease in elderly patients with bipolar disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190(4):359–360. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.029868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kales H. Medical Comorbidity in Late-Life Bipolar Disorder. In: Sajatovic M, Blow FC, editors. Bipolar Disorder in Later Life. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntyre RS, et al. Medical Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder: Implications for Functional Outcomes and Health Service Utilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1140–1144. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntyre RS, et al. Bipolar disorder and diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment implications. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;17(2):83–93. doi: 10.1080/10401230590932380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. Trends in aging--United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(6):101–4. 106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeste DV, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next 2 decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(9):848–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]