Abstract

Background and Aims

The Campanulaceae is a large cosmopolitan family, but is understudied in terms of germination, and seed biology in general. Small seed mass (usually in the range 10–200 µg) is a noteworthy trait of the family, and having small seeds is commonly associated with a light requirement. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of light on germination in 131 taxa of the Campanulaceae family, from all five continents of its distribution.

Methods

For all taxa, seed germination was tested in light (8 or 12 h photoperiod) and continuous darkness under constant and alternating temperatures. For four taxa, the effect of light on germination was examined over a wide range of temperatures on a thermogradient plate, and the possible substitution of the light requirement by gibberellic acid and nitrate was examined in ten taxa.

Key Results

For all 131 taxa, seed germination was higher in light than in darkness for every temperature tested. Across species, the light requirement decreased significantly with increasing seed mass. For larger seeded species, germination in the dark reached higher levels under alternating than under constant temperatures. Gibberellic acid promoted germination in darkness whereas nitrates partially substituted for a light requirement only in species showing some dark germination.

Conclusions

A light requirement for germination, observed in virtually all taxa examined, constitutes a collective characteristic of the family. It is postulated that smaller seeded taxa might germinate only on the soil surface or at shallow depths, while larger seeded species might additionally germinate when buried in the soil if cued to do so by fluctuating temperatures.

Keywords: Campanulaceae, germination, light requirement, seed mass, constant vs. alternating temperatures, gibberellic acid, nitrate

INTRODUCTION

Seed responses to light can control the timing of germination in the field, impacting seedling survival, as well as growth and fitness in subsequent life stages (Pons, 2000). Seeds requiring light for germination are usually small in size (Pons, 2000; Fenner and Thompson, 2005). Milberg et al. (2000) suggested that a light response and seed mass coevolved as an adaptation to ensure germination of small-seeded species only when close to the soil surface. On the other hand, a phylogenetic component of light-promoted germination – regardless of seed size – has been postulated (Fenner and Thompson, 2005).

Temperature is a major factor modulating seed responses to light: a seed may require light to germinate at a given temperature but not at other temperatures (Pons, 2000). Moreover, for some species, temperature fluctuations can fully or partially substitute for the light requirement (Baskin and Baskin, 1998). The amplitude of soil temperature fluctuations is highest on or close to the surface of bare soil and in vegetation gaps (Probert, 2000; Daws et al., 2002).

Phytochromes are well known to mediate light-promoted germination; they are also known to increase the amount of bioactive gibberellins in seeds (Bewley et al., 2013). Thus, exogenously applied gibberellins promote germination of photorequiring seeds in darkness. Conversely, nitrates which are naturally occurring in the soil, can also substitute for the light requirement in some cases (Hilhorst and Karssen, 2000; Daws et al., 2002).

The Campanulaceae sensu lato (APG III, 2009) is the 26th largest plant family (Stevens, 2001 onwards) and comprises 85 genera (including Halacsyella; Stefanović et al., 2008) and approx. 2300 species (Lammers, 2007a). It is divided into five subfamilies following morphological data: Lobelioideae, Campanu-loideae, Cyphioideae, Nemacladoideae and Cyphocarpoideae (Brummitt, 2007; Lammers, 2007a). Campanulaceae is cosmopolitan in distribution; taxa are most often herbaceous perennials that form capsular fruits with usually numerous small seeds (Lammers, 2007b). Ecologically, the family is extremely diverse, occurring in a variety of habitats except the major deserts. Though exceptions are numerous, there is a discernible trend among Campanuloideae for more open habitats, while many Lobelioideae tend to be associated with forested areas (Lammers, 2007b).

The Campanulaceae is highly understudied in terms of germination. The effect of light on the induction of seed germination has been studied for just 20 species, spanning ten genera (Brightmore, 1968; Linhart, 1976; Baskin and Baskin, 1979, 1984; Grime et al., 1981; Farmer and Spence, 1987; Lesica, 1992; Mariko and Kachi, 1995; Teketay and Granström, 1997; Morgan, 1998; Teketay, 1998; Bachmann et al., 2005; Baskin et al., 2005; Jankowska-Blaszczuk and Daws, 2007; Carta et al., 2013). For all species tested to date, exposure to light promotes germination, except for Howellia aquatilis (Lesica, 1992).

In this study, we aim to determine the effect of light on germination for 131 taxa in the Campanulaceae. Specifically we (1) tested germination in light and darkness at constant and alternating temperatures; (2) associated the response to light with seed mass and alternating vs. constant temperatures; and (3) examined whether gibberellic acid and nitrate can substitute for the light requirement. Although the Campanulaceae representatives studied here were collected across a broad range of habitats globally, the majority of seed samples were collected from Europe and predominantly Greece (50 taxa). From the biodiversity conservation point of view, it is noteworthy to mention that Campanulaceae is the family with the highest degree of endemism (54 %, approx. 63 taxa) in Greece (Georghiou and Delipetrou, 2010).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Seed material

Seeds of 131 taxa of Campanulaceae were either collected specifically for this study or provided from seed banks and collaborators. Seed mass ranged between 5 and 1060 µg. The taxa are classified to 27 genera and three subfamilies, and are native to all five continents of distribution: Africa (four taxa), America (26 taxa), Asia (13 taxa), Europe (75 taxa), Oceania (13 taxa). The vast majority of seed collections (121 out of 131) derive from wild-growing populations and the remainder from botanical gardens. Information on these 131 taxa is presented in Table 1. Germination experiments were carried out at least 2 months after seed collection, which would have satisfied any after-ripening requirements. Seeds were stored initially at room temperature and then, after a few months, at 10 °C with silica gel. Seed samples obtained from seed banks were also stored at 10 °C with silica gel.

Table 1.

Germination data, seed mass and country of provenance for the 131 taxa studied

| ID no. | Taxon | Constant |

Alternating |

PGIconst | PGIalt | Seed mass (μg) | Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | FGL | FGD | T | FGL | FGD | ||||||

| 1 | Adenophora remotiflora | 20 | 76 | 4 | 0·95 | 209 | China | ||||

| 2 | Asyneuma chinense | 25 | 88 | 0 | 1·00 | 48 | China | ||||

| 3 | Asyneuma giganteum | 10 | 93 | 77 | 20/10 | 92 | 53 | 0·17 | 0·43 | 330 | Greece |

| 4 | Asyneuma limonifolium subsp. limonifolium | 10 | 90 | 86 | 20/10 | 87 | 54 | 0·04 | 0·40 | 185 | Greece |

| 5 | Asyneuma pilcheri | 15 | 59 | 0 | 20/10 | 91 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 14 | Greece |

| 6 | Campanula aizoides | 5 | 19 | 0 | 1·00 | 203 | Greece | ||||

| 7 | Campanula aizoon | 5 | 20 | 0 | 1·00 | 275 | Greece | ||||

| 8 | Campanula albanica subsp. albanica | 5 | 48 | 0 | 20/10 | 1 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 87 | Greece |

| 9 | Campanula americana | 25 | 5 | 0 | 25/15 | 56 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 149 | U.S.A. |

| 10 | Campanula andrewsii subsp. andrewsii | 15 | 93 | 26 | 20/10 | 96 | 31 | 0·72 | 0·67 | 28 | Greece |

| 11 | Campanula asperuloides | 5 | 86 | 0 | 20/10 | 30 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 19 | Greece |

| 12 | Campanula barbata | 25 | 80 | 0 | 25/15 | 87 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 61 | France |

| 13 | Campanula calaminthifolia | 15 | 63 | 0 | 20/10 | 59 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 75 | Greece |

| 14 | Campanula camptoclada | 20 | 56 | 0 | 25/15 | 96 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·98 | 32 | Jordan |

| 15 | Campanula celsii subsp. carystea | 15 | 97 | 0 | 25/15 | 87 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 26 | Greece |

| 16 | Campanula celsii subsp. celsii | 15 | 87 | 0 | 25/15 | 87 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·99 | 24 | Greece |

| 17 | Campanula celsii subsp. parnesia | 10 | 100 | 0 | 20/10 | 87 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 26 | Greece |

| 18 | Campanula celsii subsp. spathulifolia | 15 | 99 | 0 | 20/10 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 27 | Greece |

| 19 | Campanula cervicaria | 15 | 100 | 59 | 20/10 | 100 | 75 | 0·41 | 0·25 | 55 | France |

| 20 | Campanula chalcidica | 25 | 67 | 0 | 25/15 | 16 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 21 | Greece |

| 21 | Campanula cochleariifolia | 15 | 67 | 0 | 25/15 | 86 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 63 | France |

| 22 | Campanula cretica | 15 | 99 | 24 | 20/10 | 97 | 7 | 0·76 | 0·93 | 104 | Greece |

| 23 | Campanula creutzburgii | 15 | 45 | 0 | 20/10 | 88 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 18 | Greece |

| 24 | Campanula cymaea | 15 | 85 | 1 | 25/15 | 85 | 4 | 0·99 | 0·95 | 65 | Greece |

| 25 | Campanula drabifolia | 15 | 90 | 0 | 30/20 | 91 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 9 | Greece |

| 26 | Campanula dulcis | 15 | 93 | 0 | 20/10 | 98 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·99 | 15 | Saudi Arabia |

| 27 | Campanula elatinoides | 15 | 80 | 0 | 20/10 | 71 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 51 | Italy |

| 28 | Campanula erinus | 15 | 97 | 0 | 20/10 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 11 | Morocco |

| 29 | Campanula formanekiana | 15 | 94 | 2 | 0·98 | 138 | Greece | ||||

| 30 | Campanula garganica subsp. cephallenica | 15 | 44 | 0 | 25/15 | 33 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 27 | Greece |

| 31 | Campanula glomerata subsp. glomerata | 25 | 62 | 0 | 25/15 | 47 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 114 | England |

| 32 | Campanula goulimyi | 15 | 96 | 0 | 20/10 | 97 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 30 | Greece |

| 33 | Campanula hagielia | 15 | 97 | 0 | 20/10 | 98 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 25 | Greece |

| 34 | Campanula incurva | 15 | 98 | 0 | 20/10 | 85 | 3 | 1·00 | 0·97 | 58 | Greece |

| 35 | Campanula lanata | 15 | 84 | 0 | 20/10 | 86 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 21 | Bulgaria |

| 36 | Campanula latifolia subsp. latifolia | 10 | 96 | 10 | 20/10 | 94 | 25 | 0·90 | 0·74 | 201 | Italy |

| 37 | Campanula lingulata | 15 | 91 | 8 | 20/10 | 91 | 0 | 0·91 | 1·00 | 136 | Greece |

| 38 | Campanula lyrata subsp. lyrata | 15 | 97 | 0 | 25/15 | 84 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 27 | Greece |

| 39 | Campanula merxmuelleri | 25 | 99 | 0 | 25/15 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 33 | Greece |

| 40 | Campanula mollis | 15 | 98 | 0 | 25/15 | 94 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | Spain |

| 41 | Campanula oreadum | 5 | 7 | 0 | 1·00 | 160 | Greece | ||||

| 42 | Campanula pangea | 25 | 91 | 0 | 25/15 | 85 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 47 | Greece |

| 43 | Campanula patula | 20 | 3 | 0 | 25/15 | 46 | 2 | 1·00 | 0·33 | 20 | Bulgaria |

| 44 | Campanula pelviformis | 15 | 98 | 11 | 20/10 | 97 | 12 | 0·89 | 0·88 | 35 | Greece |

| 45 | Campanula peregrina | 20 | 74 | 0 | 25/15 | 82 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 23 | Lebanon |

| 46 | Campanula persicifolia subsp. persicifolia | 15 | 97 | 0 | 20/10 | 83 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 30 | Greece |

| 47 | Campanula prenanthoides | 5 | 53 | 0 | 1·00 | 77 | USA | ||||

| 48 | Campanula punctata | 20 | 79 | 0 | 25/15 | 67 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 67 | South Korea |

| 49 | Campanula pyramidalis | 20 | 72 | 9 | 20/10 | 94 | 92 | 0·88 | −0·28 | 136 | Croatia |

| 50 | Campanula raineri | 5 | 12 | 0 | 1·00 | 51 | Italy | ||||

| 51 | Campanula ramosissima | 10 | 87 | 37 | 25/15 | 74 | 2 | 0·57 | 0·98 | 10 | Greece |

| 52 | Campanula rapunculoides | 15 | 100 | 0 | 20/10 | 100 | 46 | 1·00 | 0·54 | 207 | Bulgaria |

| 53 | Campanula rapunculus | 20 | 83 | 8 | 20/10 | 87 | 23 | 0·90 | 0·72 | 25 | Jordan |

| 54 | Campanula rhodensis | 20 | 47 | 0 | 20/10 | 74 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·98 | 15 | Greece |

| 55 | Campanula rhomboidalis | 5 | 19 | 0 | 1·00 | 72 | France | ||||

| 56 | Campanula rotundifolia | 15 | 90 | 1 | 20/10 | 80 | 11 | 0·99 | 0·88 | 53 | England |

| 57 | Campanula sartorii | 15 | 63 | 0 | 20/10 | 62 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 56 | Greece |

| 58 | Campanula saxatilis subsp. saxatilis | 15 | 74 | 6 | 25/15 | 91 | 9 | 0·92 | 0·88 | 56 | Greece |

| 59 | Campanula scheuchzeri | 15 | 15 | 0 | 20/10 | 28 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 63 | France |

| 60 | Campanula sparsa | 15 | 96 | 12 | 20/10 | 95 | 3 | 0·88 | 0·97 | 19 | Greece |

| 61 | Campanula spatulata subsp. filicaulis | 15 | 75 | 8 | 20/10 | 89 | 9 | 0·89 | 0·88 | 30 | Greece |

| 62 | Campanula spatulata subsp. spatulata | 10 | 92 | 63 | 20/10 | 92 | 37 | 0·32 | 0·60 | 18 | Greece |

| 63 | Campanula spatulata subsp. spruneriana | 15 | 90 | 60 | 25/15 | 60 | 52 | 0·33 | 0·42 | 22 | Greece |

| 64 | Campanula spicata | 15 | 76 | 0 | 20/10 | 73 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 36 | Italy |

| 65 | Campanula strigosa | 5 | 12 | 0 | 1·00 | 59 | Jordan | ||||

| 66 | Campanula thessala | 20 | 100 | 0 | 1·00 | 45 | Greece | ||||

| 67 | Campanula thyrsoides subsp. thyrsoides | 20 | 97 | 0 | 25/15 | 92 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·99 | 114 | France |

| 68 | Campanula topaliana subsp. cordifolia | 15 | 100 | 0 | 25/15 | 94 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·99 | 22 | Greece |

| 69 | Campanula topaliana subsp. topaliana | 15 | 100 | 2 | 20/10 | 91 | 0 | 0·98 | 1·00 | 19 | Greece |

| 70 | Campanula trachelium subsp. athoa | 15 | 96 | 0 | 25/15 | 96 | 24 | 1·00 | 0·75 | 80 | Bulgaria |

| 71 | Campanula tubulosa | 15 | 92 | 1 | 25/15 | 96 | 4 | 0·99 | 0·96 | 30 | Greece |

| 72 | Campanula versicolor | 15 | 85 | 38 | 25/15 | 87 | 72 | 0·55 | 0·15 | 48 | Greece |

| 73 | Canarina canariensis | 15 | 98 | 58 | 20/10 | 98 | 61 | 0·41 | 0·38 | 1060 | Spain |

| 74 | Clermontia hawaiiensis | 20 | 99 | 0 | 20/10 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 116 | USA |

| 75 | Clermontia kakeana | 20 | 98 | 0 | 20/10 | 93 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 69 | USA |

| 76 | Clermontia oblongifolia | 20 | 83 | 0 | 20/10 | 79 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 39 | USA |

| 77 | Clermontia parviflora | 20 | 95 | 0 | 20/10 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 36 | USA |

| 78 | Codonopsis clematidea | 15 | 61 | 11 | 20/10 | 62 | 22 | 0·82 | 0·64 | 699 | Kyrgyzstan |

| 79 | Cyananthus inflatus | 25 | 85 | 2 | 25/15 | 91 | 0 | 0·98 | 1·00 | 47 | China |

| 80 | Cyanea angustifolia | 15 | 95 | 0 | 20/10 | 76 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 98 | USA |

| 81 | Delissea rhytidosperma | 20 | 96 | 5 | 25/15 | 95 | 80 | 0·95 | 0·17 | 158 | USA |

| 82 | Delissea subcordata | 15 | 74 | 0 | 20/10 | 96 | 6 | 1·00 | 0·92 | 268 | USA |

| 83 | Downingia bacigalupii | 15 | 52 | 0 | 15/5 | 81 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 55 | USA |

| 84 | Downingia bicornuta | 5 | 80 | 0 | 15/5 | 94 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 28 | USA |

| 85 | Downingia cuspidata | 15 | 72 | 0 | 15/5 | 68 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 22 | USA |

| 86 | Downingia elegans | 15 | 98 | 0 | 20/10 | 96 | 3 | 1·00 | 0·97 | 40 | USA |

| 87 | Edraianthus graminifolius subsp. graminifolius | 5 | 84 | 1 | 0·99 | 397 | Greece | ||||

| 88 | Halacsyella parnassica | 5 | 22 | 4 | 0·82 | 563 | Greece | ||||

| 89 | Hippobroma longiflora | 25 | 93 | 0 | 30/20 | 93 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 60 | Mexico |

| 90 | Isotoma axillaris | 25 | 56 | 0 | 1·00 | 74 | Australia | ||||

| 91 | Isotoma hypocrateriformis | 10 | 6 | 0 | 20/10 | 7 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | Australia |

| 92 | Isotoma luticola | 20 | 70 | 0 | 1·00 | 5 | Australia | ||||

| 93 | Isotoma scapigera | 20 | 5 | 0 | 1·00 | 8 | Australia | ||||

| 94 | Jasione heldreichii | 20 | 87 | 19 | 20/10 | 80 | 14 | 0·78 | 0·84 | 29 | Greece |

| 95 | Jasione montana subsp. montana | 15 | 98 | 0 | 20/10 | 99 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | Italy |

| 96 | Jasione orbiculata | 15 | 87 | 4 | 0·95 | 31 | Greece | ||||

| 97 | Legousia falcata | 5 | 100 | 0 | 20/10 | 9 | 2 | 1·00 | 0·98 | 149 | Greece |

| 98 | Legousia pentagonia | 5 | 42 | 0 | 1·00 | 274 | Jordan | ||||

| 99 | Lobelia anceps | 15 | 1 | 0 | 20/10 | 96 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 15 | Australia |

| 100 | Lobelia appendiculata | 15 | 26 | 0 | 35/20 | 2 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | USA |

| 101 | Lobelia cardinalis | 10 | 78 | 0 | 25/15 | 97 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 37 | USA |

| 102 | Lobelia djurensis | 20 | 97 | 0 | 20/10 | 85 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 10 | Mali |

| 103 | Lobelia fenestralis | 15 | 13 | 0 | 30/15 | 39 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 10 | USA |

| 104 | Lobelia grayana | 15 | 78 | 0 | 25/15 | 64 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 20 | USA |

| 105 | Lobelia hypoleuca | 25 | 90 | 0 | 25/15 | 94 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 20 | USA |

| 106 | Lobelia inflata | 25 | 59 | 0 | 20/10 | 40 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 27 | USA |

| 107 | Lobelia oahuense | 25 | 95 | 0 | 25/15 | 96 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | USA |

| 108 | Lobelia physaloides | 15 | 93 | 0 | 20/10 | 93 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 89 | New Zealand |

| 109 | Lobelia seguinii | 20 | 98 | 0 | 25/15 | 100 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 16 | China |

| 110 | Lobelia simplicicaulis | 20 | 82 | 0 | 1·00 | 28 | Australia | ||||

| 111 | Lobelia siphilitica | 20 | 4 | 0 | 20/10 | 85 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 30 | USA |

| 112 | Lobelia spicata | 25 | 3 | 0 | 20/10 | 17 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 21 | USA |

| 113 | Michauxia campanuloides | 15 | 100 | 6 | 20/10 | 100 | 2 | 0·94 | 0·98 | 96 | Lebanon |

| 114 | Monopsis debilis | 15 | 89 | 0 | 20/10 | 87 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | Australia |

| 115 | Musschia aurea | 20 | 92 | 0 | 25/15 | 91 | 1 | 1·00 | 0·99 | 16 | Portugal |

| 116 | Nemacladus glanduliferus | 10 | 4 | 0 | 30/15 | 2 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 53 | USA |

| 117 | Petromarula pinnata | 20 | 76 | 3 | 25/15 | 61 | 22 | 0·96 | 0·71 | 17 | Greece |

| 118 | Phyteuma betonicifolium | 15 | 87 | 0 | 20/10 | 94 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 41 | Italy |

| 119 | Phyteuma hemisphaericum | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1·00 | 44 | Italy | ||||

| 120 | Solenopsis minuta subsp. annua | 15 | 91 | 16 | 20/10 | 92 | 34 | 0·82 | 0·63 | 7 | Greece |

| 121 | Trachelium caeruleum | 20 | 90 | 0 | 25/15 | 93 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 11 | Spain |

| 122 | Triodanis perfoliata | 15 | 58 | 4 | 0·93 | 19 | USA | ||||

| 123 | Wahlenbergia capillaris | 15 | 4 | 0 | 1·00 | 12 | Australia | ||||

| 124 | Wahlenbergia ceracea | 20 | 2 | 0 | 1·00 | 22 | Australia | ||||

| 125 | Wahlenbergia gracilis | 30 | 64 | 0 | 1·00 | 26 | Australia | ||||

| 126 | Wahlenbergia hederacea | 20 | 20 | 0 | 1·00 | 26 | England | ||||

| 127 | Wahlenbergia linarioides | 15 | 97 | 6 | 20/10 | 89 | 3 | 0·94 | 0·97 | 40 | Chile |

| 128 | Wahlenbergia luteola | 20 | 55 | 0 | 20/10 | 47 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 19 | Australia |

| 129 | Wahlenbergia perrottetii | 30 | 80 | 0 | 35/20 | 60 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 17 | Burkina Faso |

| 130 | Wahlenbergia preissii | 15 | 81 | 0 | 20/10 | 85 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 12 | Australia |

| 131 | Wahlenbergia undulata | 25 | 80 | 0 | 35/20 | 90 | 0 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 14 | Swaziland |

T, temperature (°C); FGL and FGD, final germination percentage in light and darkness, respectively; PGI, photorequirement germination index at constant temperatures (PGIconst) and alternating temperatures in the dark and constant temperatures in the light (PGIalt).

Effect of light on germination

The role of light was examined at constant and alternating temperatures with daily illumination of 8 or 12 h per day (light treatment) and in continuous darkness (dark treatment). The temperatures presented in Table 1 correspond either to the single temperature applied or to the optimal temperature (among several tested); the experiments were planned depending on seed availability. Only one constant or alternating temperature was tested in 19 and 37 taxa, respectively. Light exposure in alternating temperatures regimes coincided with the period with the elevated temperature. Seeds were placed in Petri dishes containing either 1 % agar or filter paper wetted with distilled water. To ensure there was no effect of germination media on germination results, a preliminary experiment was conducted on both media using Campanula andrewsii subsp. andrewsii and C. drabifolia. The results of these tests were not statistically different. There were five samples of 20 seeds each for the light treatment and one sample with 100 seeds for the dark treatment. The single sample used in the dark was due to experimental space limitations and, mainly, to the difficulties in handling these tiny seeds in complete darkness. Seeds germinated in the light treatment were counted and removed regularly. For incubation in darkness, seeds were sown in the dark, then Petri dishes were wrapped in double aluminium foil and placed in metal boxes or black plastic bags; seed germination was scored with a single final measurement, after no further germination had been observed for at least 1 week in the concurrent experiment with seeds in the light. Germination percentages were corrected for viable seeds, based on post-experiment cut-tests and morphological examinations of the embryo. For the majority of the taxa studied, empty seeds constituted less than approx. 10 % of each seed sample, except for three taxa (4, 13 and 41; Table 1), probably a result of poor seed quality.

For each species, we derived an index of light requirement for germination at constant temperatures (photo-requirement germination index; PGI) such that:

| (1) |

where FGDconst is the percentage germination at constant temperatures in the dark and FGLconst is the percentage germination at constant temperatures in the light.

The PGI results in values between 0 and 1: a value of 0 corresponds to the germination percentage being equal in both light and darkness, while a value of 1 corresponds to germination only occurring in the light. A relative light germination (RLG) index has also been used previously (e.g. Milberg et al., 2000; Jankowska-Blaszczuk and Daws, 2007), and also results in values of 0–1. However, RLG index values from 0 to <0·5 refer to the situation where germination in the dark is greater than in the light. This situation did not occur for any of the species tested in the current study. The PGI had the advantage of resulting in a larger spread of values. However, RLG values were also calculated and compared with the PGI, and resulted in quantitatively similar overall results (data not shown).

The PGI was also calculated using germination at alternating temperatures in the dark and constant temperatures in the light. This enabled the hypothesis that alternating temperatures are able to substitute for a light requirement in dark conditions to be tested. Thus:

| (2) |

where FGDalt is the percentage germination at alternating temperatures in the dark and FGLconst is the percentage germination in constant temperatures in the light.

Germination experiments on the two-way thermogradient plate

The effect of light at a wide range of constant and alternating temperatures was examined in seeds of four taxa (16, 22, 49 and 52; Table 1) on two thermogradient plates (Model GRD1, Grant Instruments, Cambridge, UK; Murdoch et al., 1989). One thermogradient plate was set with a 12 h/12 h photoperiod and one in continuous darkness. Thermoperiod was set to 14 h day/10 h night, ranging from 5 to 35 °C, and seeds were illuminated 1 h after the onset of the day temperature. Seeds were placed in Petri dishes with 1 % agar (a total of 36 dishes per taxon). The dishes were arranged on the surface of the thermogradient plate in a 12 × 12 array. Thus, the 144 individual Petri dishes were arranged uniformly for the four taxa such that there were 36 different temperature combinations for each taxon. Twenty seeds were used per Petri dish; seeds remained on the thermogradient plates for 30 d.

Substitution for light requirement

To determine if gibberellic acid and nitrates can substitute for the light requirement, seed germination of ten taxa (12, 28, 38, 42, 60, 62, 81, 94, 97 and 120; Table 1) was tested in continuous darkness with GA3 1000 ppm or KNO3 10 mm. Two controls with distilled water were used, one under daily illuminations (12 h per day) and one in continuous darkness. One Petri dish of 100 seeds was placed under each test condition. All experiments were conducted at 15 °C, except for taxa numbered 62 (20/10 °C), 81 (20 °C) and 97 (10 °C).

Statistical analysis

Across species, a generalized linear model implemented in Minitab 16 (Minitab Inc., Pennsylvania, USA) was used to test for an effect of alternating vs. constant temperatures on PGI (i.e. do PGIalt and PGIconst differ?). A total of 124 out of 131 taxa with percentage germination >10 % were included in the model. The model included log10 seed mass as a covariate and the seed mass × temperature regime interaction term. The inclusion of the interaction term allowed the test of the hypothesis that in larger seeded species, alternating temperatures can substitute for light requirement (i.e. across species does PGIalt decrease more rapidly with increasing seed mass than PGIconst?). The analyses were also run with a smaller data set, including only taxa with final germination >70 %. This gave quantitatively similar results to the analyses with the larger data set; therefore, the results are not presented separately.

For each one of the four Campanula species (16, 22, 49 and 52; Table 1) tested on the thermogradient plate, germination data were analysed using binary logistic regression implemented in Minitab 16. Data were examined with respect to (1) ‘day’ temperature; (2) ‘night’ temperature; (3) light; (4) the magnitude of the diurnal temperature fluctuation (i.e. |day–night temperature|); and (5) the light × alternating temperature interaction term. The inclusion of the light × alternating temperature interaction term allowed us to test whether the effect of alternating temperatures depended on the light regime, i.e. whether alternating temperatures can substitute for the light requirement. This approach assumes that each individual seed in the population is a statistically independent unit (since each individual seed can either germinate or not) and the goodness of fit of these models was assessed using Wald tests (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001).

RESULTS

Light requirement in incubators

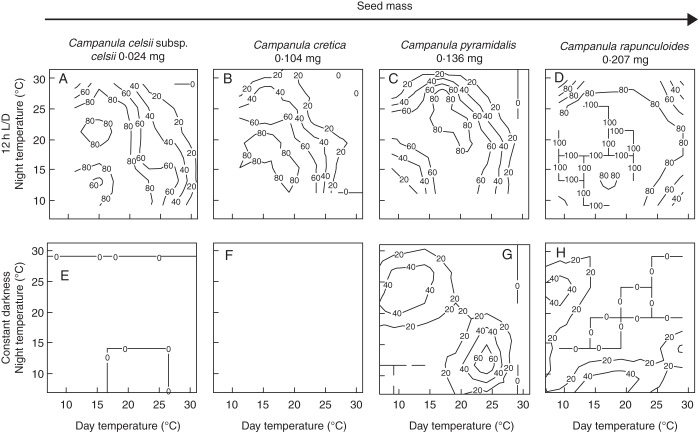

For all 131 taxa, seed germination was higher in light than in darkness at both constant and alternating temperatures. Successful germination (considered as such when final germination exceeded 70 %) was achieved for the majority of the taxa studied (97 taxa) while final germination in light was >30 % in 114 taxa (Fig. 1). The PGIconst values varied between 0·04 and 1·00, with 118 taxa having PGIconst >0·8 and 95 taxa with an absolute light requirement (PGIconst = 1·00).

Fig. 1.

Final germination percentage in the light (white) and dark (black) in the temperature regime with the highest germination for 114 taxa (FG ≥30 %). The outer circle corresponds to 100 % and the circle interval is set at 10 %. Taxa are arranged in order of increasing seed mass (clockwise from the starting point, vertical arrow).

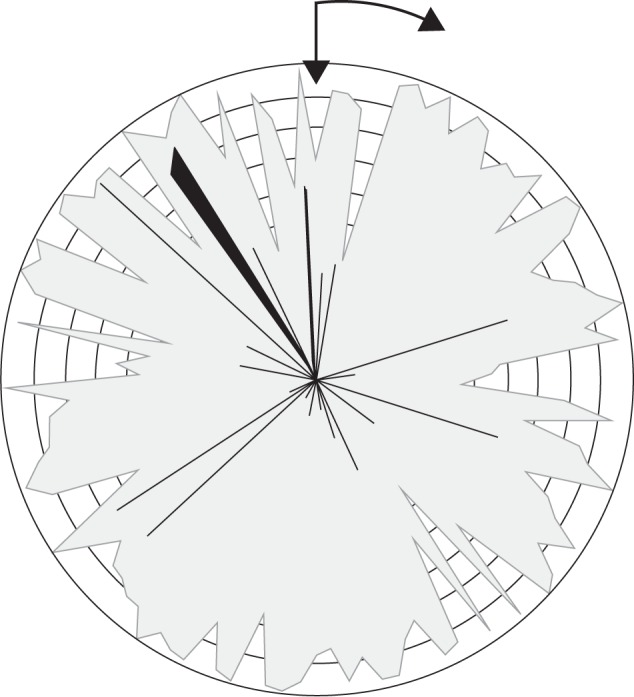

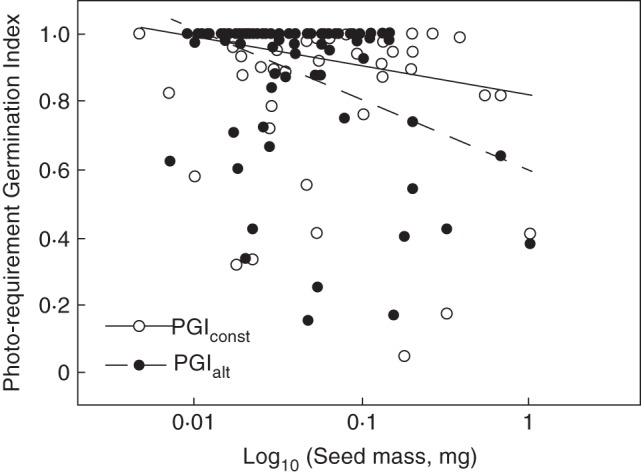

Across species, PGI decreased significantly with increasing seed mass: larger seeded species were less dependent on light for germination (generalized linear model, F1,224 = 24·10, P = 0·000; Fig. 2). In addition, across species, there was a significant difference between PGI calculated using constant temperatures in the dark (PGIconst) and alternating temperatures in the dark (PGIalt) (F1,224 = 6·04, P = 0·015) and a significant interaction between seed mass and the effect of alternating vs. constant temperatures in the dark (generalized linear model, F1,224 = 3·95, P = 0·048). This is manifest in Fig. 2 by the more negative slope for PGIalt [y = –0·089ln(x) + 0·603, R2 = 0·135, d.f. = 102, P < 0·001] than for PGIconst [y = –0·038ln(x) + 0·8174, R2 = 0·052, d.f. = 122, P < 0·02]. This result and Fig. 2 suggest that especially for larger seeded species, germination in the dark reached higher levels under alternating rather than under constant temperatures.

Fig. 2.

Effect of seed mass on the photorequirement germination index in constant (PGIconst) and alternating temperatures (PGIalt) for 124 and 104 Campanulaceae taxa, respectively, with FG >10 %.

Light requirement in the thermogradient plate

Germination for all four species reached ≥95 % in the 12 h light regime, with germination decreasing at the extreme low and high day and night temperatures. Germination was generally highest at approx. 20 °C (Fig. 3A–D). For the two smallest seeded species (C. cretica and C. celsii subsp. celsii), germination was ≤5 % at all temperatures in the constant dark treatment (Fig. 3E, F). For C. celsii subsp. celsii, there was a significant effect of light on germination (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = 5·25, P < 0·001), and neither an effect of alternating temperatures (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = 0·89, P > 0·05) nor an interaction between alternating temperatures and light was found (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = –1·28, P > 0·05). While light was clearly required for germination of C. cretica, this could not be tested in the logistic model due to a failure for model convergence resulting from a total absence of germination in the dark. For the two larger seeded species, there was also a significant light effect on germination (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = 16·01 and 9·26 for C. rapunculoides and C. pyramidalis, respectively, P < 0·001; Fig. 3). However, for these two species, up to 85 % germination was also recorded in the dark treatments, but only at temperature regimes with a difference between day and night temperature of approx. 10 °C (Fig. 3G, H): for both species there was a significant interaction between light and alternating temperatures (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = –8·74 and –4·15 for C. rapunculoides and C. pyramidalis, respectively, P < 0·001). The effect of alternating temperatures on germination was significant for C. rapunculoides (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = 4·63, P < 0·001) but not for C. pyramidalis (binary logistic regression, Wald test statistic = 1·72, P > 0·05).

Fig. 3.

Contour plots of the final germination percentage in the light (12 h photoperiod, A–D) and in continuous darkness (E–H) for four species of Campanula exposed to a wide range of combinations of day and night temperature on a two-way thermogradient plate. Species are arranged from left to right in order of increasing seed mass. The contour interval is set at 20 %.

Substitution for light requirement

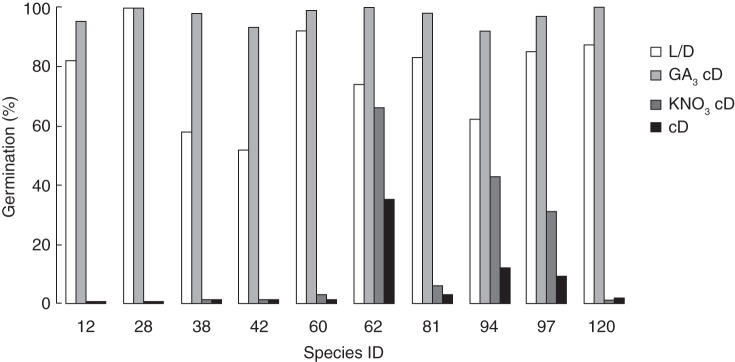

The gibberellin GA3 substituted for the light requirement in all ten species examined; moreover, its application resulted in even higher values of final germination compared with the light treatment (Fig. 4). On the other hand, KNO3 only partially promoted dark germination in three species (62, 94 and 97; Table 1), in which the percentage germination in darkness without KNO3 was >5 %.

Fig. 4.

Final germination percentage in the light (12 h photoperiod, L/D) and in continuous darkness with GA3 1000 ppm (GA3 cD), KNO3 10 mm (KNO3 cD) or distilled water (cD) for ten species (see Table 1 for species' ID numbers).

DISCUSSION

The effect of light on Campanulaceae seed germination has been studied in representatives of all five continents and for three out of five subfamilies. In this work, 19 previously unstudied genera and 123 unstudied taxa of the Campanulaceae were shown to have seeds with germination promoted by light. A light requirement for germination, observed in virtually all taxa examined, constitutes a collective characteristic of the family, apparently regardless of habitat type (sand dunes, wetlands, shrublands, forests, cliffs and rock crevices, montane and alpine meadows), life form (phanerophyte, nanophanerophyte, chamaephyte, hemicryptophyte, geophyte, therophyte) and climatic conditions (tropical–sub-tropical, mediterranean, temperate, continental, alpine). Statistical analysis aiming to discriminate variations of light requirement among different ecological factors have however proven unsuccessful (data not shown).

A light requirement for germination was stronger in smaller than in larger seeded species of the Campanulaceae: PGI decreased with increasing seed mass. Final germination of 27 of the taxa included in the analysis was <70 %. Since a portion of seeds in these seed samples may have failed to germinate due to dormancy, our data indicate that, at least for non-dormant seeds, small-seeded taxa are more likely to require light for germination. This relationship has been reported previously for local flora species (Grime et al., 1981; Pons, 1991), desert species (Hammouda and Bakr, 1969; Jiménez-Aguilar and Flores, 2010), temperate herbaceous species (Milberg et al., 2000), neotropical pioneer species (Pearson et al., 2002), herbaceous species of northern temperate deciduous forests (Jankowska-Blaszczuk and Daws, 2007) and pioneer tree species from the Central Amazon (Aud and Ferraz, 2012). In a study of 136 taxa of the Cactaceae family (Flores et al., 2011) seed mass was associated with the RLG index only when all taxa were included in the analysis and not when only taxa with germination >60 or 70 % were included in the analysis. However, for 28 temperate grassland species, seed mass and percentage germination in light or dark were not correlated (Morgan, 1998).

The low R2 values observed in this current study indicate a significant variation in light responses in relation to seed mass. One limitation of using light requirement indices (either the RLG index or PGI) is that data sets typically contain a preponderance of taxa with either an absolute light requirement (RLG index or PGI of 1) or no light requirement (RLG index of 0·5 or PGI of 0) (e.g. Milberg et al., 2000; Flores et al., 2011; this study): few taxa have intermediate requirements. Consequently, data are unlikely to fit along a single fitted line and low R2 values are likely, as found in this and other studies (e.g. Milberg et al., 2000; Flores et al., 2011). Nonetheless, the key point is that these analyses indicate a statistically significant, negative slope for the relationship between PGI and seed mass, i.e. a trend towards larger seeded species being less likely to require light for germination. This limitation could be addressed by simplifying the taxon level response to light to a binomial variable, i.e. seeds either do or do not respond to light. However, this would risk losing significant amounts of information present in the data.

Indifference to light or higher germination in dark conditions has only previously been reported in two Campanulaceae species. Willis and Groves (1991) reported higher germination of Wahlenbergia stricta in the dark than in the light. However, this contrasts with both Hitchmough et al. (1989) and McIntyre (1990) who reported light-stimulated germination in W. stricta, and our current study, where all nine Wahlenbergia species studied required light for germination (Table 1). Willis and Groves (1991) reported that, for the purpose of scoring germination, seeds were exposed to light every 2–3 d, which may have been sufficient to stimulate germination in their ‘dark’ treatment. For ‘dark’ treatments this highlights the importance of only scoring seeds at the end of the concurrent light treatment. For Howellia aquatilis, seed germination has been reported to be indifferent to light (Lesica, 1992). Although seed mass is not mentioned for this species, calculations based on seed dimensions (approx. 1 × 3 mm long) suggest a seed mass >300 µg. Consequently, H. aquatilis seems to be one of the largest seeded species in the Campanulaceae and its indifference to light is consistent with the results of the present study.

Light penetration falls below 0·01 % at a depth of 4 mm in sandy soil or 1 mm in dark soil, while increasing soil depth also leads to a gradual decline of the red:far red ratio (Benvenuti, 1995). Thus a light requirement for germination acts as a surface-sensing mechanism, enabling small seeds with limited nutrient reserves to germinate when found near the soil surface rather than from depths from which they are unable to emerge physically (Bond et al., 1999; Daws et al., 2007). In addition, species with light-requiring seeds can form soil seed banks and germinate at a subsequent stage, after soil disturbance (Grime et al., 1981).

Alternating temperatures can fully or partially substitute for light requirement in the Campanulaceae. This has been reported previously in various taxa, e.g. Rumex obtusifolius (Taylorson and Hendricks, 1972), Polygonum persicaria (Vincent and Roberts, 1977) and Chenopodium album (Tang et al., 2008). Substitution of light requirement by alternating temperatures in the Campanulaceae is mostly associated with larger seeded species. Fluctuating temperatures can act as a sensing mechanism for both soil depth and vegetation cover, due to greater fluctuation caused by direct sun exposure. Since soil temperature fluctuations can be experienced by seeds buried at depths greater than those from which small seeds can physically emerge (Jankowska-Blaszczuk and Daws, 2007), our data suggest that substitution of a light requirement by alternating temperatures is a characteristic of larger, light-promoted seeds, i.e. those with enough nutrients to emerge from greater soil depths, as has been previously reported by Thompson and Grime (1983). For neotropical tree species, Pearson et al. (2002) reported that while small seeds are generally light requiring, larger seeded non-light-promoted species were likely to germinate in response to fluctuating temperatures.

Substitution of the light requirement by nitrates, observed in three out of nine Campanulaceae, can be explained in terms of plant competition. Covering vegetation decreases the concentration of nitrates in the soil due to acquisition by plants; thus, an increase in soil nitrate concentration is typically the result of some kind of disturbance (Fenner and Thompson, 2005). Promotion of germination in darkness by nitrates in photorequiring Helichrysum stoechas subsp. barrelieri seeds is particularly important in fire-prone Mediterranean ecosystems (Doussi and Thanos, 1997). The active form of phytochrome is transferred to the cell nucleus where it is known to activate gibberellin biosynthesis (Oh et al., 2009); this fact may explain why exogenously applied gibberellins (such as those used here) can substitute for a light requirement in seed germination. Light requirement for germination was entirely substituted by gibberellic acid for all Campanulaceae taxa examined.

To conclude, most species of the Campanulaceae family have a light requirement for germination, substituted by gibberellic acid (although it is certainly not part of the natural environment of seeds) and partially also by nitrate (only in species that germinated to some extent in darkness). The influence of light on germination was much stronger in smaller than in larger seeded species; thus germination is prevented when seeds are buried deep in the soil. Larger seeded species can germinate in deeper soil depths in the presence of fluctuating temperatures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Seed Banks of the following Institutions for the seed material provided: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Paris Natural History Museum; Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Chania; Botanic Garden of Pavia University; General Directorate for Natural Heritage and Biodiversity Regional Ministry for Agriculture and Water, Region of Murcia; Canarian Botanical Garden ‘Viera y Clavijo’; Hawai'i Center for Conservation Research and Training; and the Botanical Garden of Cordoba. We are grateful to Dr Thomas Raus, Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem, for checking and correcting the Latin names of plants in Table 1. K.K. also thanks Apostolos Kaltsis (NKUA, for assistance in seed collections), Helen Everett and Lindsay Robb (Wakehurst Place, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for laboratory help) and Dr Robin Probert (RBGK, for advice). Part of the experimental work took place at the Institute of Mediterranean forest ecosystems and forest products technology, HAO (Demeter). This work was partially supported by a scholarship from the Greek Foundation of State Scholarships.

LITERATURE CITED

- APG III. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2009;161:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Aud FF, Ferraz IDK. Seed size influence on germination responses to light and temperature of seven pioneer tree species from the Central Amazon. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) 2012;84:759–766. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652012000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann U, Hensen I, Partzsch M. Is Campanula glomerata threatened by competition of expanding grasses? Plant Ecology. 2005;180:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin CC, Baskin JM. Seeds: ecology, biogeography and evolution of dormancy and germination. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin CC, Baskin JM, Yoshinaga A. Morphophysiological dormancy in seeds of six endemic lobelioid shrubs (Campanulaceae) from the montane zone in Hawaii. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2005;83:1630–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin JM, Baskin CC. The ecological life cycle of the cedar glade endemic Lobelia gattingeri. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 1979;106:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin JM, Baskin CC. The ecological life cycle of Campanula americana in northcentral Kentucky. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 1984;111:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti S. Soil light penetration and dormancy of jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) Weed Science. 1995;43:389–393. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley JD, Bradford KJ, Hilhorst HWM, Nonogaki H. Seeds: physiology of development, germination and dormancy. 3rd edn. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bond WJ, Honig M, Maze KE. Seed size and seedling emergence: an allometric relationship and some ecological implications. Oecologia. 1999;120:132–136. doi: 10.1007/s004420050841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brightmore D. Lobelia urens L. Journal of Ecology. 1968;56:613–620. [Google Scholar]

- Brummitt RK. Campanulaceae. In: Heywood VH, Brummitt RK, Culham A, Seberg O, editors. Flowering plant families of the world. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; 2007. pp. 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Carta A, Bedini G, Müller JV, Probert RJ. Comparative seed dormancy and germination of eight annual species of ephemeral wetland vegetation in a Mediterranean climate. Plant Ecology. 2013;214:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Daws MI, Burslem DFRP, Crabtree LM, Kirkman P, Mullins CE, Dalling JW. Differences in seed germination responses may promote coexistence of four sympatric Piper species. Functional Ecology. 2002;16:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- Daws MI, Ballard C, Mullins CE, et al. Allometric relationships between seed mass and seedling characteristics reveal trade-offs for neotropical gap-dependent species. Oecologia. 2007;154:445–454. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussi MA, Thanos CA. Ecophysiology of seed germination in composites inhabiting fire-prone Mediterranean ecosystems. In: Ellis RH, Black M, Murdoch AJ, Hong TD, editors. Basic and Applied Aspects of Seed Biology: Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Seeds, Reading, 1995. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AM, Spence DHN. Flowering, germination and zonation of the submerged aquatic plant Lobelia dortmanna L. Journal of Ecology. 1987;75:1065–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner M, Thompson K. The ecology of seeds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Jurado E, Chapa-Vargas L, et al. Seeds photoblastism and its relationship with some plant traits in 136 cacti taxa. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2011;71:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Georghiou K, Delipetrou P. Patterns and traits of the endemic plants of Greece. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010;162:130–422. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Mason G, Curtis AV, et al. A comparative study of germination characteristics in a local flora. Journal of Ecology. 1981;69:1017–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda MA, Bakr ZY. Some aspects of germination of desert seeds. Phyton. 1969;13:183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hilhorst H, Karssen C. Effect of chemical environment on seed germination. In: Fenner M, editor. Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities. Wallingford: CAB International; 2000. pp. 293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchmough J, Berkeley S, Cross R. Flowering grasslands in the Australian landscape. Landscape Australia. 1989;4:394–403. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska-Blaszczuk M, Daws MI. Impact of red:far red ratios on germination of temperate forest herbs in relation to shade tolerance, seed mass and persistence in the soil. Functional Ecology. 2007;21:1055–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Aguilar A, Flores J. Effect of light on seed germination of succulent species from the southern Chihuahuan Desert: comparing germinability and relative light germination. Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development. 2010;12:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lammers TG. World checklist and bibliography of Campanulaceae. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Lammers TG. Campanulaceae. In: Kubitzki K, editor. The families and genera of vascular plants. Vol. 8. Berlin: Springer; 2007b. pp. 26–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lesica P. Autecology of the endangered plant Howellia aquatilis; implications for management and reserve design. Ecological Applications. 1992;2:411–421. doi: 10.2307/1941876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhart YB. Density-dependent seed germination strategies in colonizing versus non-colonizing plant species. Journal of Ecology. 1976;64:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Mariko S, Kachi N. Seed ecology of Lobelia boninensis Koidz. (Campanulaceae), an endemic species in the Bonin Islands (Japan) Plant Species Biology. 1995;10:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre S. Germination in eight native species of herbaceous dicots and implications for their use in revegetation. Victorian Naturalist. 1990;107:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Milberg P, Andersson L, Thompson K. Large-seeded species are less dependent on light for germination than small-seeded ones. Seed Science Research. 2000;10:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JW. Comparative germination responses of 28 temperate grassland species. Australian Journal of Botany. 1998;46:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch AJ, Roberts EH, Goedert CO. A model for germination responses to alternating temperatures. Annals of Botany. 1989;63:97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Kang H, Yamaguchi S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genes targeted by PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3-LIKE5 during seed germination in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:403–419. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson TRH, Burslem DFRP, Mullins CE, Dalling JW. Germination ecology of neotropical pioneers: interacting effects of environmental conditions and seed size. Ecology. 2002;83:2798–2807. [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL. Dormancy, germination and mortality of seeds in a chalk–grassland flora. Journal of Ecology. 1991;79:765–780. [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL. Seed responses to light. In: Fenner M, editor. Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities. Wallingford: CAB International; 2000. pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Probert RJ. The role of temperature in the regulation of seed dormancy and germination. In: Fenner M, editor. Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities. Wallingford: CAB International; 2000. pp. 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanović S, Lakušić D, Kuzmina M, Međedović S, Tan K, Stevanović V. Molecular phylogeny of Edraianthus (Grassy Bells; Campanulaceae) based on non-coding plastid DNA sequences. Taxon. 2008;57:452–475. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens PF. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. 2001 onwards Version 12, July 2012 [and more or less continuously updated since]. http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/ (accessed 10 June 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th edn. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tang D-S, Hamayun M, Ko Y-M, Zhang Y-P, Kang S-M, Lee I-J. Role of red light, temperature, stratification and nitrogen in breaking seed dormancy of Chenopodium album L. Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology. 2008;11:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Taylorson RB, Hendricks SB. Interactions of light and a temperature shift on seed germination. Plant Physiology. 1972;49:127–130. doi: 10.1104/pp.49.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teketay D. Germination ecology of three endemic species (Inula confertiflora, Hypericum quartinianum and Lobelia rhynchopetalum) from Ethiopia. Tropical Ecology. 1998;39:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Teketay D, Granström A. Germination ecology of forest species from the highlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 1997;14:793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Grime JP. A comparative study of germination responses to diurnally-fluctuating temperatures. Journal of Applied Ecology. 1983;20:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent EM, Roberts EH. Interactions of light, nitrate and alternating temperature in promoting the germination of dormant seeds of common weed species. Seed Science and Technology. 1977;5:659–670. [Google Scholar]

- Willis AJ, Groves RH. Temperature and light effects on the germination of seven native forbs. Australian Journal of Botany. 1991;39:219–228. [Google Scholar]