Abstract

The extent and experiences of youths' caretaking of their adolescent sisters' children have been assessed in two longitudinal studies. The first study examines the caretaking patterns of 132 Latino and African American youth during middle and late adolescence. The second study involves 110 Latino youth whose teenage sister has recently given birth. Youth are studied at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum. In both studies, girls provide more hours of care than boys, and in Study 1, girls' hours of care significantly increase with age whereas boys' hours of caretaking decrease. Girls provide more care when their sisters are older and when their mothers provide many hours of care, whereas boys provide less care when their mothers provide more care and when they have many siblings. Results of both studies reveal age, gender, and across-time differences in the extent of care, type of caretaking activities, and experiences in providing care.

Keywords: adolescents, adolescent mothers, African Americans, caregiving, Mexican Americans, sibling caretaking

In families in which a teenager has a baby, all available family members are often pooled to help care for the adolescent's child (Burton, 1990). The marshalling of kinship support is a necessary social and economic adaptation to the unique conditions such families face (Bould, 1993; Burton, 1996), including little public support for the parent and child, single parenting, low male partner participation, and poverty. However, although the child care provided by the teenager and the teen's mother is often emphasized, the child care provided by the teenager's siblings is either overlooked entirely or noted only as auxiliary or backup care (Burton, 1995). Child care provided by siblings though may be favored over other strategies because it best uses available and affordable family personnel and because it frees the teen's mother of such work so she can engage in more economically productive work outside the home. Sibling care is also a preferred option because younger siblings are likely to be early or middle adolescent themselves and thus old enough to help with child care but not too old so that they are out of the house entirely (Polatnick, 2002).

The child care provided by the siblings of parenting teens, however, is virtually unstudied in the United States. Very little is known about the extent of youths' caregiving within these households or youths' experiences in this type of child care. Do they enjoy it? Are they learning about children and parenting by providing such care? What kinds of care activities do youth provide, and are there gender, age, or racial or ethnic patterns to this type of family care? Below we review the literature and discuss our expectations pertaining to the following four issues of sibling care: (a) gender, age, and racial or ethnic differences; (b) experiences gained in caretaking; (c) the context of providing care (whether it is provided alone or with others); and (d) familial–contextual factors related to care. Much of the literature cited pertains to sibling caregiving, or youth caring for their younger siblings. Although sibling caregiving is similar to niece or nephew care, there are nuances to each situation. For example, sibling caregivers are often supervised by their mothers (Bryant, 1992), whereas youth caregivers in teenage childbearing families may be jointly supervised by both their sisters and mothers, or they may be more likely to be unsupervised (Burton, 1995).

Gender, Age, and Racial or Ethnic Differences in Caretaking

Girls typically engage in more sibling caretaking than boys and begin a year or two earlier (Zukow-Goldring, 2002). Classic studies within the family work literature have noted that girls perform far more of the stereotypical female tasks within the family (which include caring for siblings) than do boys (Berk, 1985; Huber & Spitz, 1983). More recent developmental studies report that girls spend significantly more time than boys caring for family members (Call, Mortimer, & Shanahan, 1995) and that girls' hours of sibling care increase relative to boys across adolescence (Gager, Cooney, & Call, 1999). Girls may value and desire greater participation in the care of children than boys based on gender role expectations and gender socialization (Garey, Hansen, Hertz, & MacDonald, 2002). For example, testing a feminine care hypothesis, Kroska (2003) found that women considered child care empowering, satisfying, and an affirmation of their femininity. Thus, gender patterns likely exist in specific caregiving activities, with girls more apt to help directly with child care and boys to help more in activities that nevertheless facilitate family assistance (such as managing house maintenance or upkeep; Burton, 2006).

Regarding age effects, the enhanced competence and maturity of older adolescents increase the likelihood that they will take on, or be asked to provide, more caregiving responsibilities than younger children. However, with older age comes competing demands for youth to engage in their own activities (e.g., working at paid jobs, involvement in school activities, and more demanding school requirements), not to mention social activities with peers and in romantic relationships. It may be that early adolescent youths within the family are asked to take on a large share of the child care, with younger and older children not able, willing, or available to provide such care (Polatnick, 2002).

The cultural–ethnic context of the family is also important for understanding the extent of youth family care. There have been well-established findings from African American teenage childbearing families regarding child fostering, grandparental care, and socially distributed kin care (Burton, 1996; Stack, 1974). Similarly, Latino families are typically embedded within a large extended-kin network that engages in high rates of crossgenerational support (Luna et al., 1996; Zambrana, 1995). Kin-based child care systems have been found to be stronger in African American families and Latino families relative to Anglo-American families (Uttal, 1999; and reviewed in McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000), but less is known about whether sibling care patterns might differ between modern-day African American and Latino families.

Two sociocultural factors that might play a role in creating potential differences in sibling care between African American and Latino families are each group's different immigration patterns and differences in gender socialization and familistic values. Regarding the former, because of the migration patterns of Mexicans into the United States, many Mexican American Latino families are recent immigrants and still have key relatives living in Mexico (Buriel & DeMent, 1997). Having relatives—and therefore potential child care providers—residing in Mexico would likely boost the level of sibling care within these families. In contrast, African American families' kin are less likely to live outside the United States and thus conceivably more available to provide kin care (McAdoo, 1995). In addition, findings from an ethnographic study showed that children within recently immigrated families tend to take on more of their families' kin care needs than children from other ethnic groups who have not recently immigrated (Valenzuela, 1999).

Regarding differences in gender socialization, there is some evidence that Latina girls hold more traditional gender norms and values than African American girls (East, 1998) and that Latino families have more traditional gender roles—with women deferring to men and with “women's work” centered around child care and family care—than non-Latino families (Saldana, Dassori, & Miller, 1999; Valenzuela, 1999). Latino adolescents also typically place a strong emphasis on family duty and responsibility and hold strong familistic values (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). Such values and attitudes, as well as the greater family dispersion patterns and recent immigrant status within many Latino families, may act to increase Latino youths' level of family care relative to that of African American youths.

Experiences Gained in Providing Care

Youths' experiences in providing care are also important in assessing its impacts. For example, researchers in the family work literature have noted that children's feelings about their work contributions to the family are often more important for their development than the actual work itself (Call, 1996; Goodnow & Lawrence, 2001). Is it provided willingly and spontaneously, or begrudgingly and resentfully? Positive experiences would support the prosocial and altruistic role of children cooperating and helping their family in ways in which they are able (Bryant, 1992). But resentful care (youth arguing about it or feeling mad about having to do it), with coercion on the part of family members, would indicate that adolescents are obliged (or “conscripted”) to respond to their family's needs (Stack & Burton, 1993). The qualitative work of Dodson and Dickert (2004) keenly portrays the often coercive nature of girls' family labor in low-income households in the United States, with deceptive methods often used to instill girls' help. Certainly the amount of kin care relates to experiences in caretaking, with excessive amounts likely linked to feeling used or unappreciated.

The Context of Providing Care

In describing the extent of youth's child care, it is important to distinguish between primary and secondary caretaking (Weisner, 1982). Primary care is carried out alone wherein the primary or exclusive responsibility of caring for the child is assumed. Primary child care undertaken by a family member other than the mother typically occurs in situations where the mother is unable, unfit, or unwilling to care for her child (because of work demands, drug or alcohol use or addiction, or chronic illness; Burton, 2007; Sears & Sheppard, 2004). In such cases, primary–solitary care is typically carried out by older daughters within the family (Burton, 1996).

In contrast, secondary or backup, ancillary care is provided in the presence of others and is perceived of as child care “help” (Burton, 1995). Backup or ancillary child care is often engaged in with the intent to provide caretaking instruction or socialization for future parenting (Weisner, 1987). Backup care typically involves younger children who can assist in child care but not manage it independently. The second study presented in this article distinguishes between primary and secondary caretaking provided by youth at two time points, with the expectation that secondary (or collaborative) care will decrease across time whereas primary care (provided alone) will increase.

Familial–Contextual Factors Related to Care

Family structural–household factors, such as family size and the presence of grandparents, most certainly influence the extent of children's involvement in family care. Within teenage parenting families, grandparents, aunts, and even great-grandparents often take on large portions of the caretaking of the teen's child (Burton, 1995, 1996). The presence of all such kin would likely reduce the child care involvement by adolescent siblings. The influence of family size though on youths' child care is not a straight forward case. Although larger families have a greater availability of kin to provide care, they also create more housework than smaller families (Shelton & John, 1996). Because girls typically perform more sibling care than boys (Zukow-Goldring, 2002), one would expect that the number of sisters within a household would be negatively related to youths' level of child care. Similarly, the number of brothers would be expected to be positively related to any one sibling's hours of care (because boys contribute to the family's workload but less often partake in its management; Gager et al., 1999). Finally, the presence of a father figure in the household would be expected to lessen youths' level of niece or nephew care if only because it may free the teen's mother of needing to work outside the home and thereby allow her to help care for the teen's child. The first study presented in this report has information on family size and family composition, as well as the extent of caregiving provided by youths' mothers. The second study also has information on family size and household composition, as well as the extent of caregiving provided by youths' mothers and sisters. We expected that sibling child care will be greatest in larger families (particularly those with many male children in the household), in families in which youths' mothers and sisters provide minimal child care, and in households that lack a father or grandparent.

This Research

This article presents results of two longitudinal studies of youths' care-taking of their adolescent sisters' children. This research is from one group of investigators who conducted two separate studies approximately 4 years apart. In the first study, we examined associations between youths' hours of child care, their race or ethnicity, and several family contextual factors when youth were middle adolescent and late adolescent. In the second study, we examined associations among youths' hours of care (provided alone and in the presence of others), several features of the family's household composition, and youths' experiences in providing care (whether they liked it or were learning about children by providing such care). These relations were examined when the niece or nephew was on average 6 weeks old and 6 months old. In both studies, we also examined trends related to youths' gender, age, and across-time effects for the extent of care provided, experiences in providing care, and the specific child care activities undertaken.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants in the first study were part of an overall research investigation involving 146 early adolescents who had an older teenage childbearing sister. All youth were recruited into the study by first identifying eligible older sisters. Older sisters were primigravida, between 15 and 19 years of age, either Mexican American Latina or African American, and were recruited during their pregnancy or within 3 months postpartum. Only Latino and African American families were the focus of this study because these groups have the highest teenage birth rates (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2007). Eligible older sisters were identified at several local Planned Parenthood Clinics and a university hospital Teen Obstetric Clinic in a metropolitan area in southern California. The younger siblings of the pregnant or parenting teen were eligible to participate in the study if they were between 11 and 15 years of age (at enrollment) and they were currently living with their older sister. In all study families, only one teenager was either currently pregnant for the first time or parenting her first child; no other child had experienced or caused a teenage pregnancy. Thus, in all families, the older sister's pregnancy (and subsequent childbearing) was the first to occur within the family. Ninety percent of all eligible families invited to participate did so.

The data presented in this report were gathered at a first and second follow-up of the initial intake. (The primary variable of interest [i.e., siblings' time in child care] was not assessed at intake because many families were recruited while the older teenage sister was still pregnant.) Follow-Up 1 was conducted 1.5 years after the initial intake, and Follow-Up 2 occurred 3.3 years after Follow-Up 1. Data for the follow-ups were collected between 1996 and 1999. Of the 146 younger siblings who participated at intake, 140 were relocated at Follow-Up 1 and reinterviewed (or 96%). Of these, 132 were still living with their teenage sister and her child and provided information on the number of hours of child care. At Follow-Up 2, 124 youth were relocated and reinterviewed (or 94% of those who participated at Follow-Up 1). All of these 124 youth were living with their sister and her child at the second follow-up. These youth comprise the study sample for the current analyses, or 132 youth at Follow-Up 1 and 124 youth at Follow-Up 2.

Younger sibling participants were an average age of 13.6 years at intake (SD = 1.9), 15.1 years at Follow-Up 1, and 18.4 years at Follow-Up 2. At Follow-Up 1, 55% of participants were female, 65% were Latino, and 35% were African American. Youth who participated at Follow-Up 2 did not differ significantly in background characteristics (e.g., race or ethnicity, age, family income) from youth who did not participate at Follow-Up 2. Twenty-four younger sisters had become mothers themselves by Follow-Up 2, but this was unrelated to the extent of caregiving provided to their older sister's child (r =−.10). Older sisters were an average age of 17.6 years at the birth of their child (SD =1.4), 20 years at Follow-Up 1, and 23 years at Follow-Up 2. At the second follow-up, many older sisters were working (40%), some were attending school (13%), some were doing both (17%), and a sizeable percentage was doing neither (30%). The older sisters' children were on average 15 months old at Follow-Up 1 (age range: 6 months to 19 months) and 4.6 years at Follow-Up 2 (SD =1.5). Fifty-three percent of the older sisters' children were boys. Most study families were economically disadvantaged. At Follow-Up 1, 53% of families were receiving some form of governmental financial assistance, and the total annual family income was $16,750 for an average household size of six individuals. Fifty-six percent of households had a father or father figure present, and 12% had a grandparent present.

Procedure

At each assessment, study families were visited in their homes by two female research assistants who were fluent in Spanish. All youth completed a short interview and a self-administered questionnaire (in English). The home visit at both follow-ups lasted about 1 hr. All participants were paid $10 at each assessment and all were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Measures

The study questionnaire contained approximately 200 questions at Follow-Up 1 and 250 questions at Follow-Up 2, with several skip patterns so that most participants did not complete all questions. The questionnaires at both times of assessment had an approximate third-grade reading level (as ascertained by the Flesch–Kincaid readability method). Scale scores were formed by averaging all of the items unless otherwise noted. The study interview (at both follow-ups) included questions about who was living in the household at that time and the age of coresiding family members.

Hours of child care

The number of hours per week that youth cared for their teenage sister's child was asked in the interview with younger siblings at both follow-ups. After the appropriate sister and child had been identified, the interviewer asked participants, “How many hours a week do you take care of or look after your teenage sister's child (even in the presence of others)?” Youths' mothers also responded to this question at both study follow-ups.

Experiences in providing child care

Youth who indicated that they cared for their sister's child at least some of the time were asked on the questionnaire to respond to the following questions: “How much do you like taking care of your sister's child?” “Do you ever feel mad about having to look after your sister's child?” “Do you ever argue with your sister about having to look after her child?” and “Does looking after your sister's child ever interfere with the things you want to do?” Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with high scores indicating liking a lot, frequent arguing, feeling mad often, and frequent interfering. Participants were also asked how true the following two statements were for them: “I feel like I'm learning a lot about children by looking after my sister's child,” and “I feel like I'm learning a lot about parenting by looking after my sister's child.” Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 = no, really not true and 5 = yes, really true. These items were asked at Follow-Up 2 only.

Results

Hours of child care across age and by gender and race or ethnicity

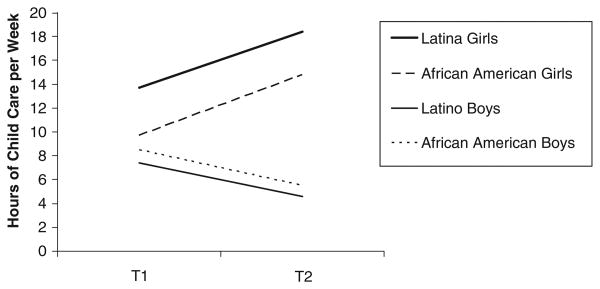

The average hours of child care per week at Follow-Ups 1 and 2 for Latino and African American boys and girls are shown in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1. There was large variability in the number of hours of care at both time points, or between 0 and 85 hr per week at Follow-Up 1, and between 0 and 90 hr per week at Follow-Up 2. Most youth however provided some level of care, with only two girls and four boys at Follow-Up 1 and one girl and three boys at Follow-Up 2 providing zero hours of care. Significant percentages of youth provided large amounts of care; that is, 27% reported providing 20 hr or more of child care a week at Follow-Up 1, and 25% reported providing 20 hr or more of caretaking a week at Follow-Up 2.

Table 1. Mean Number of Hours per Week Younger Siblings Cared for Their Teenage Sister's Child (Study 1).

| Follow-Up 1 | Follow-Up 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Younger Sibling | M | N | M | N |

| Female | 12.2 | 72 | 17.1 | 67 |

| Latina | 13.7 | 49 | 18.4 | 45 |

| African American | 9.7 | 23 | 14.8 | 22 |

| Male | 7.6 | 60 | 5.1 | 57 |

| Latino | 7.4 | 37 | 4.6 | 35 |

| African American | 8.5 | 23 | 5.5 | 22 |

| Latino | 11.2 | 86 | 12.5 | 80 |

| African American | 9.2 | 46 | 10.0 | 44 |

| Total | 10.3 | 132 | 11.6 | 124 |

| Mean age (years) | 15.1 | 18.4 | ||

| SD | 1.9 | 1.7 | ||

Figure 1. Average Hours of Child Care per Week Across Age by Gender and Race or Ethnicity.

Note: Youths' mean age at Time 1 was 15.1 years (n =132), and their mean age at Time 2 was 18.5 years (n =121) (Study 1).

To determine whether levels of child care varied across time, by gender, and by race or ethnicity, a 2 (time) × 2 (gender) × 2 (race or ethnicity) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was computed on the hours of child care provided. Youths' age was not associated with their level of care at either follow-up, so age was not included as a covariate in these analyses. The F value for the three-way repeated measures ANOVA (Time × Gender × Race or ethnicity) was not significant, F(3, 114) < 1. Results of each of the three two-way interaction effects indicated a significant gender × across-Time effect, F(2, 115) = 19.39, p < .001, with girls significantly increasing their hours of care across time relative to boys, who decreased their hours of care. Results of the three main effects indicated a significant gender effect, F(2, 115) = 9.63, p < .001, with girls providing significantly more hours of care than boys at both time points. Results also indicated that Latina girls tended to provide more care than African American girls at both time points, F(1, 66) = 3.80, p < .06.

Experiences in providing care

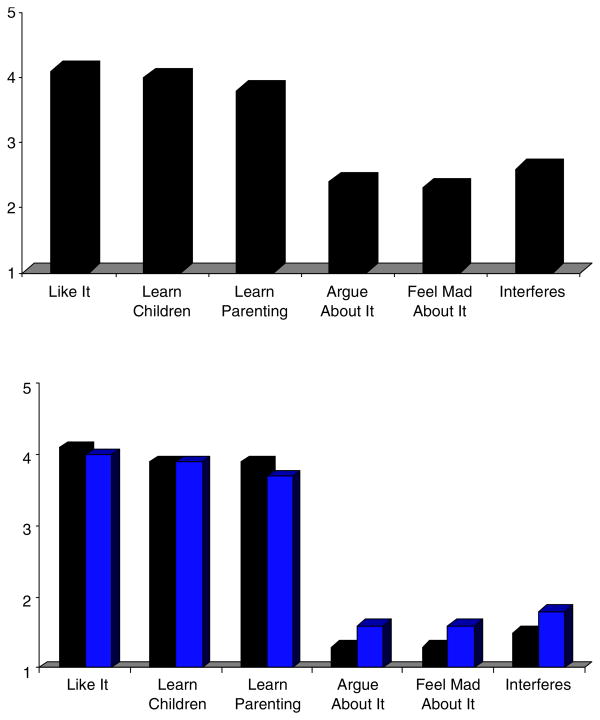

Figure 2 shows the mean ratings of youths' responses to their experiences in providing care as reported during late adolescence (top graph). Most youth indicated that they liked providing care and that they were learning about children and parenting by providing such care. However, 34% of youth indicated that they argued with their sister sometimes, often, or a lot about providing care; 27% responded that they felt mad sometimes, often, or a lot about having to provide care; and 43% indicated that providing care interfered with their own activities at least sometimes. Multiple analyses of variance testing gender, age, and race or ethnicity effects revealed significant gender differences, F(6, 118) = 2.26, p < .05, and a tendency for a significant age group effect, F(6, 118) = 2.09, p < .06, and racial or ethnic differences, F(6, 118) = 1.92, p < .10. Specifically, girls were more likely than boys to report arguing about providing care, F(1, 120) = 4.63, p < .05, and to feel mad about having to provide it, F(1, 120) = 9.27, p < .01. Younger adolescents (those ≤18.5 years) and older adolescents (>18.5 years) were categorized based on a median split. Younger adolescents were more likely than older adolescents to report feeling mad about providing care, F(1, 120) = 4.14, p < .05, and that it interfered with their own activities, F(1, 120) = 4.67, p < .05. When racial or ethnic differences were examined, Latino youth were more likely than African American youth to report that they were learning about children by providing care, F(1, 120) = 4.85, p < .05.

Figure 2. Average Ratings of Youths' Experiences in Providing Child Care During Late Adolescence (top figure; mean age 18.5 years, Study 1) and at 6 Weeks and 6 Months Postpartum (bottom figure; mean age 14 years, Study 2).

Results of partial correlations between hours of care provided during late adolescence and youths' experiences in providing care (controlling for gender and race or ethnicity) revealed two significant associations: Many hours of care was associated with feeling that one was learning about children and that one was learning about parenting by providing such care (r = .25, p < .05, and r = .32, p < .01, respectively).

Associations between youths' hours of care and family context factors

Table 2 shows the correlations between boys' and girls' hours of care (at each follow-up) and several household composition factors, such as the number of siblings and grandparents who lived in the household and whether the youths' father was present. Three significant associations emerged for both boys and girls. Specifically, boys provided fewer hours of care (at both study time points) when their mothers provided more hours of care. In addition, boys provided fewer hours of care during late adolescence when they had more coresiding siblings. Girls however provided more hours of care when their mothers also provided many hours of care and when their parenting sister was older (during middle adolescence only).

Table 2. Correlations Between Sibling Care and Family Context Factors (Study 1).

| Hours of Child Care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Males | Females | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Follow-Up 1 | Follow-Up 2 | Follow-Up 1 | Follow-Up 2 | |

| Older sister's age at delivery | −.06 | .21 | .43** | .03 |

| Hours of care mother provides | ||||

| Follow-up 1 (n = 87) | −.32* | −.12 | .39** | .17 |

| Follow-up 2 (n = 76) | −.10 | −.34* | .07 | .30* |

| Number of sisters one lives witha | .01 | −.15 | .14 | .17 |

| Number of brothers one lives witha | −.07 | −.20 | −.11 | −.02 |

| Number of siblings one lives witha | −.05 | −.29* | .11 | .13 |

| Lives with a fatherb | −.23 | −.21 | .05 | .04 |

| Lives with a grandparentc | .20 | .16 | −.16 | −.13 |

Note: n = 132 at Follow-Up 1, and n = 124 at Follow-Up 2. All correlations are partial correlations controlling for race or ethnicity.

Six years of age and older.

Whether the youths' father was present. Coded as 1 = yes, 0 = no.

Coded as 0 = none, 1 = one grandparent, 2 = lives with two grandparents.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants of the second study were 110 Mexican American younger siblings of parenting teens. Youth were recruited when their older teenage sister was in her last trimester of pregnancy. Youth in this study were assessed at four time points: during their sister's third trimester of pregnancy, at 6 weeks postpartum, 6 months postpartum, and 12 months postpartum. Only data from the 6-week and 6-month postpartum assessments are presented here. Similar to the first study, youth participants were recruited by first identifying eligible older sisters. Eligible older sisters were primigravida Latina teenagers who were recruited predominantly from high schools, Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program Centers, and community clinics located throughout southern California. Older sisters were between 15 and 18.9 years of age and were eligible for the study if they had a (coresiding) younger sibling between 12 and 17 years of age and no other teenager in the household had had or caused a teenage pregnancy. Thus, as in Study 1, the older sister's pregnancy (and subsequent childbearing) was the first to occur within the family. Data were collected between 2004 and 2006.

One hundred twenty youth were assessed during their sister's final stages of pregnancy, 110 of whom participated at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum (or 92% of those originally enrolled). Youth were an average age of 14.0 years at 6 weeks postpartum (SD = 1.8) and 14.4 years at 6 months postpartum. Of the 110 youth participating, 66 were female (60%). Most youth were born in the United States (85%); the rest were born in Mexico. Older sisters were an average age of 16.9 years at birth (SD = 1.3, range: 15-19 years). At 6 months postpartum, most older sisters were going to school (70%), some were working (10%), and some were both working and going to school (17%). Sixty two of the older sister's babies were girls (56%). Most study families were low income. At intake, the total annual family income was $18,500 for an average household size of six individuals, and 66% of families were receiving some sort of governmental financial assistance at 6 weeks postpartum. Sixty-six percent of households had a father or father figure present, and 10% of families included a coresident grandparent.

Procedure

At each assessment, study families were visited in their homes by a female research assistant who was fluent in Spanish. All youth completed a short interview and a self-administered questionnaire (in English). The home visit at both study time points lasted about 1 hr. All participants were paid $10 at each time point, and all were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Measures

The study questionnaire contained approximately 100 questions at both the 6 week and 6 month postpartum visits. The questionnaires at both study time points had an approximate third-grade reading level (as ascertained by the Flesch–Kincaid readability method). All areas were assessed using identical items and response options at both study points, and the Cronbach alphas of all scales exceeded .81.

Hours of child care

The number of hours per week that youth cared for their teenage sister's child was asked in the questionnaire using the following two questions: “How many hours a week do you take care of or look after your older sister's baby alone – with no one else helping you?” and “How many hours a week do you take care of or look after your older sister's baby while your sister, mother or another family member is there with you?” A blank was provided after each question for youth to indicate the number of hours respectively. Youths' mothers and older sisters (the infant's mother) also answered these questions at both study time points.

Type of child care activities provided

Using the response options of don't do at all (1), do a little of (2), do some of (3), do a lot of (4), and do the most of (5), youth indicated on the questionnaire how often they did various caretaking activities for their sister's baby. Activities included feeding, bathing, dressing, changing diapers, etc. (shown in Table 4).

Table 4. Frequency of Child Care Activities by Gender and Across Time (Study 2).

| Child Care activities | 6 Weeks Postpartum | 6 Months Postpartum | Across-Time Effectsb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Females | Males | Effectsa | Females | Males | Effectsa | ||

| Play with baby | 3.1 | 3.0 | – | 3.3 | 3.4 | – | T |

| Feed baby | 2.5 | 2.0 | G | 2.4 | 1.7 | G | – |

| Soothe when cries | 3.0 | 2.3 | G | 2.7 | 2.5 | A | G × T |

| Bathe | 1.3 | 1.2 | – | 1.5 | 1.3 | – | T |

| Put down for nap | 2.7 | 2.1 | G | 2.4 | 1.8 | G | – |

| Put down for bed | 2.0 | 1.6 | G | 1.8 | 1.5 | – | – |

| Dress baby | 2.3 | 1.5 | G | 2.5 | 1.6 | G | T |

| Change diapers | 2.1 | 1.3 | G | 2.2 | 1.4 | G | – |

| Take baby places | 1.7 | 1.3 | G | 2.0 | 1.6 | G, A | T |

| Buy things for baby | 1.5 | 1.4 | – | 1.6 | 1.3 | G | – |

Note: Response options were 1 = don't do at all, 2 = do a little of, 3 = do some of, 4 = do a lot of, and 5 = do the most of. Dashes indicate that no gender, age, or across-time effects were found.

G = gender difference; A = an age effect.

T = a significant across-time increase; G × T = a significant Gender × Across-Time effect.

Experiences in providing care

Younger sibling participants in the second study completed the same set of questions about their experiences in providing care to their sister's child as in the first study. Response options were also identical to the first study (range 1-5), with high scores indicating liking a lot, learning a lot about children, learning a lot about parenting, frequent arguing, feeling mad often, and frequent interfering.

Results

Hours of child care by age, gender, and across time

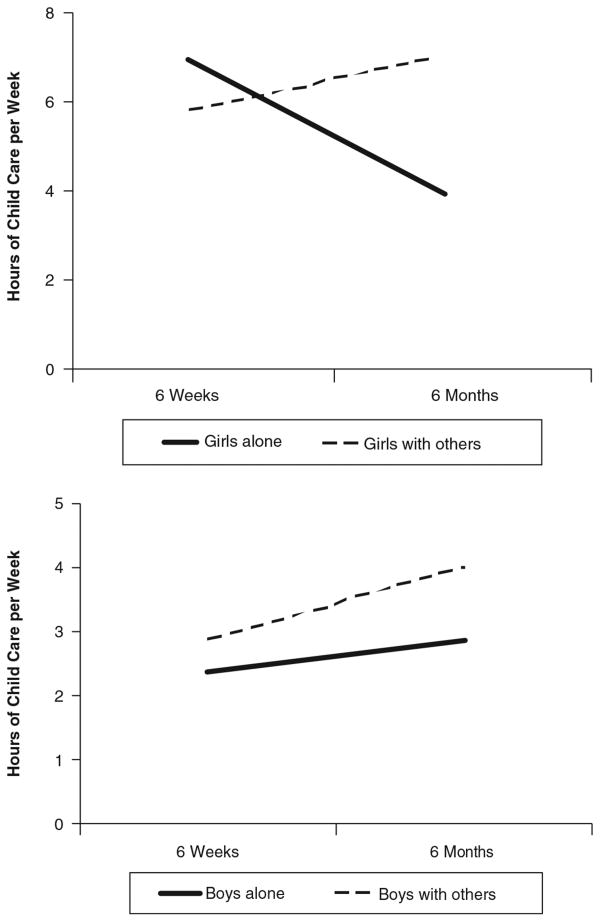

The average hours of child care provided alone was 5.2 hr per week at 6 weeks postpartum and this declined slightly to 3.6 hr per week at 6 months postpartum (shown in Table 3). The average hours of care provided in the presence of others was 4.7 hr per week at 6 weeks postpartum, and this increased to 6.4 hr per week at 6 months postpartum. Both of these differences were not statistically significant. It should be noted that unlike the levels of care observed in Study 1, relatively more youth provided no care in Study 2. At 6 weeks postpartum, 10% of youth provided zero hours of care, and 13% provided no child care at 6 months postpartum. This is probably due to the newness and fragility of the teen's baby. However, as in Study 1, significant portions of youth provided large amounts of care, with 15% of siblings reporting providing 20 hr or more of child care a week at each time point.

Table 3. Mean Hours per Week Younger Siblings Cared for Their Teenage Sister's Infant (Study 2).

| 6 Weeks | 6 Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Younger Sibling | Alone | With Others | Total | Alone | With Others | Total |

| Female (n = 66) | 7.2 | 6.0 | 13.2 | 4.1 | 7.4 | 11.5 |

| Male (n = 44) | 2.4 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 6.7 |

| Total sample | 5.2 | 4.7 | 9.9 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 10.0 |

Note: n = 110 youth. Mean age = 14 years.

To examine age and gender differences and across-time trends, a 2 × 2 × 2 (Age × Gender × Across-Time) ANOVA was computed on the hours of care provided alone and with others. Younger (≤14 years) and older (≥15 years) youth were categorized based on a median split. The three-way ANOVAs (for hours of care provided alone and hours of care provided with others) were not statistically significant. Results of each of the two-way interaction effects indicated a significant Gender × Across-Time interaction for hours of care provided alone, F(2, 108) = 3.70, p < .05, and a significant Gender × Age interaction for hours of care provided with others, F(1, 109) = 5.51, p < .05. The mean number of hours of child care provided by girls and boys alone and with others across time is shown in Figure 3. The hours of child care provided alone significantly decreased across time for girls, whereas it increased slightly for boys. Analysis of the Gender × Age interaction revealed that older girls provided significantly more hours of care while with others (8.9 hr/week) than both younger girls (2.9 hr/week; p < .001) and older boys (1.8 hr/week; p < .001). Results of the three main effects indicated a significant gender effect on hours of care provided in the presence of others, F(1, 109) = 5.18, p < .05, and a significant age effect for total hours of care provided at 6 months, F(2, 108) = 5.72, p < .01. Specifically, girls provided more hours of care in the presence of others than boys at both time points, and older youth provided more total hours of care than younger youth at 6 months postpartum (13.4 hr/week vs. 5.4 hr/week, respectively). Being foreign versus U.S.-born was not significantly related to level of child care at either time point.

Figure 3. Average Hours of Child Care per Week Provided Alone and With Others by Girls (top figure) and Boys (bottom figure) (Study 2).

Note: Youth were an average age of 14 years.

Associations between youths' hours of care and family context factors

Correlations were computed between boys' and girls' total hours of caretaking (at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum) and the following features of their family context: hours of care provided by mothers, hours of care by the older sister, older sister's age, number of sisters present within the household, number of brothers present, whether a father or father figure was present within the household, and the presence of a grandparent. Although the results indicated only 3 significant relations (out of 28 possible), all significant associations corroborate those found in Study 1. Specifically, boys provided fewer hours of care at 6 weeks postpartum when their mothers provided high amounts of care (r = −.35, p < .05), and girls provided more hours of care (at both time points) when their sisters were older (r = .30, p < .05, at 6 weeks; and r = .34, p < .05, at 6 months).

Specific child care activities by gender, age, and across time

Table 4 shows the mean frequency of particular child care activities youth provided at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum by gender. The most common child care activities engaged in were playing with the baby, feeding the baby, and soothing the baby when he or she cried. Several significant gender and age effects were found, with girls and older youth engaging in specific caregiving activities more frequently than boys and younger youth (as indicated in Table 4). Across-time tests showed that the frequency of the following activities increased for all youth across time: playing with baby, F(1, 109) = 6.75, p < .01; bathing baby, F(1, 109) = 6.05, p < .01; dressing baby, F(1, 109) = 3.53, p < .05; and taking the baby places, F(1, 109) = 13.78, p < .001. Only one significant Gender × Across-Time interaction emerged and this was for soothing the baby when he or she cried, F(2, 108) = 3.23, p < .05. Girls soothed their sisters' children less across time, whereas boys' soothing increased from 6 weeks to 6 months postpartum. However, girls still soothed their niece or nephew more than boys did at both time points.

Experiences in providing care

The mean scores of youths' experiences in providing child care are shown for the two study time points in the bottom half of Figure 2. as in Study 1, most youth reported enjoying child caretaking and learning about children and parenting by providing such care. However, in Study 2, there was a trend for youth to report stronger negative feelings about providing care at 6 months postpartum than at 6 weeks postpartum. This occurred for arguing about having to provide care, F(1, 109) = 3.93, p < .05, feeling mad about having to provide care, F(1, 109) = 9.72, p < .01, and care interfering with one's own activities, F(1, 109) = 6.02, p < .05. Youths' ratings of the learning benefits associated with child care (learning about parenting) also decreased slightly across time, F(1, 109) = 3.63, p < .06. Analyses of gender effects revealed no gender differences at 6 weeks postpartum, but at 6 months postpartum, girls were more likely than boys to report feeling mad about providing care (p < .05) and that it interfered with their own activities (p < .01). No significant associations with age were found at either time point.

Associations between youths' hours of care and experiences in providing care

The correlations between hours of care (provided alone and with others) and experiences in caretaking are shown in Table 5. Partial correlations were computed, controlling for age and gender. Consistent with our expectations, providing many hours of child care alone was associated with strong negative experiences (arguing about it, care interfering with one's own activities) at both time points. Also as hypothesized, providing many hours of child care in the presence of others was generally associated with positive experiences (liking it and learning benefits) at both 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum. Contrary to these trends, however, many hours of child care provided in the presence of others was associated with more arguing about child care at 6 weeks postpartum (r = .29, p < .01) and reports that the child care interfered with one's own activities at 6 months postpartum (r = .22, p < .05). In addition, many hours of child care provided alone at 6 months postpartum was associated with feeling that one was learning a lot about children and parenting (r = .35 and .34, respectively, p < .01). (Correlations between total hours of care and caretaking experiences from Study 1 are similar to those shown in Table 5 and can be obtained from the authors on request.)

Table 5. Correlations Between Hours of Child Care Provided Alone and With Others and Feelings About Providing Care (Study 2).

| 6 Weeks Postpartum | 6 Months Postpartum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Feelings Aout Care | Hours Aone | Hours With Others | Hours Aone | Hours With Others |

| Ague about it | .42*** | .29** | .37*** | −.00 |

| Feel mad about | .52*** | .02 | .16 | .18 |

| It interferes | .34*** | .07 | .28** | .22* |

| Like it | .10 | .33** | .14 | .41*** |

| Learn about children | −.03 | .26** | .35** | .42*** |

| Learn about parenting | −.06 | .17 | .34** | .39*** |

Note: n = 110. Correlations are partial correlations controlling for age and gender.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Sibling child care is a significant practice within families that have a teenage childbearing daughter. Results from Study 1 showed that younger siblings spent approximately 10 hr a week during middle adolescence and 12 hr a week during late adolescence caring for their teenage sister's child. Results from Study 2 indicated that youth spent 10 hr a week on average caring for their young infant niece or nephew, approximately evenly divided between care done alone and care provided in the presence of others. However, there was wide variability in the extent of caretaking in both studies, with many youth spending as much as 20 hr or more a week looking after their niece or nephew.

Results from both studies indicated that girls spent more time in child care than boys at all study time points. Results from Study 1 also showed that girls increased their hours of caretaking across adolescence, whereas boys decreased their hours of care. Results from Study 2 indicated that compared with boys, girls provided more child care in the presence of others (at both time points), and girls provided more specific child care activities (feeding, dressing, putting down for nap, changing diapers). The fact that girls spent more time in child care than boys is not surprising. Across cultures, as well as in the United States, girls almost always engage in more sibling caregiving than boys (Weisner, 1982, 1987; Weisner, Garnier, & Loucky, 1994; Zukow-Goldring, 2002). Gender norms and gender socialization likely compel girls to take a larger role in all forms of kin care than boys (Huber & Spitz, 1983; Kroska, 2003), and family obligations that stress family duty and responsibility are stronger for girls than for boys (Fuligni & Pederson, 2002). Adolescent girls' child care involvement may be consistent with some families' socialization goals, to prepare girls for their own eventual parenting, and consistent with the importance of family obligation and social interdependence, as well as to provide direct assistance to the household.

Results from Study 2 also suggested, however, that girls argued more and were more likely to feel mad about having to provide care than boys. Thus, girls' relatively higher levels of caretaking may not be completely voluntary but rather reflect an obligatory nature to girls' family care. Resentful care suggests that youth are compelled (or “conscripted”) to respond to their family's needs (Stack & Burton, 1993). Given the high-stress nature of many families that have teenage childbearing daughters (Furstenberg, 1980), girls within these families may be asked to forego their own activities to attend to family kin care needs (Dodson & Dickert, 2004). In fact, findings from Study 1 suggest that sibling care continues over the course of the young niece's or nephew's childhood. There are numerous implications of long-term sibling care, one of which is that the sibling caregiver remains in the household perhaps longer than he or she would otherwise and becomes the designated family care provider (Burton, 2007; Stack & Burton, 1993). Another ramification of long-term sibling care is that the young child has an additional consistent attachment figure so, should the teen mother or another care provider within the household leave, the younger sibling may still be present to help raise the youngster.

Findings from both studies also indicated that certain aspects of the family context were important for youths' kin care, with different factors related to girls' and boys' level of care. In both studies, boys provided less care when their mothers provided large amounts of care and (in Study 1) when boys had more siblings. In contrast, girls provided more care when their mothers provided large amounts of care (found in Study 1), and girls' hours of care was higher when their teenage childbearing sister was older (in both studies). As demonstrated in other studies, the availability of coresident kin appears to influence girls' and boys' level of care differently (Call et al., 1995; Gager et al., 1999). Daughters may be more understanding than sons to their mothers' household work and strive to relieve some of their burden (Crouter, Head, Bumpus, & McHale, 2001). Or alternatively, mothers may rely more on daughters than sons when their workload becomes excessive. In either case, these findings highlight the cooperative and dynamic nature of family kin care and corroborate the results of other studies that show the importance of family structure for youths' kin care involvement (Burton, 1995, 1996; Gager et al., 1999).

Regarding age effects, only the results from Study 2 showed that older youth provided more total hours of care than younger adolescents, or 13 hr per week on average for those age 15 and older versus only 5 hr per week for those 14 years and younger (at 6 months postpartum). Results from Study 2 also indicated that older adolescents were more likely to take their infant niece or nephew places (at both 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum) and to provide more soothing (at 6 months postpartum). In contrast, results of Study 1 showed that younger adolescents (at Follow-Up 2 or when youth participants were an average age of 18.5 years) were more likely than older adolescents to report feeling mad about caretaking and that it interfered with their own activities. Thus, although older siblings within the family are more likely entrusted with child caretaking duties, such obligations may more likely infringe on younger adolescents' time for social and/or recreational activities. Certainly, no child care arrangement is without opportunity costs and emotional burdens, and such costs should be considered even for young adult siblings (Burton, 2007; Chase, 1999).

Only one racial or ethnic difference emerged in the extent of sibling care. Specifically, results from Study 1 showed that Latina girls tended to provide more hours of care than African American girls during both middle and late adolescence. It is possible then that within Latino families, girls are more strongly socialized for kin care than are African American girls. The relatively small sample size (particularly of African American girls and boys in Study 1) precluded us from fully exploring racial or ethnic differences in sibling care and its developmental trajectories. It would be important to know the sibling care patterns of Latina and African American girls as established during early and middle childhood; the current study offers a view of their caretaking experiences only from middle adolescence onward. Perhaps Latina girls participate more in the care of their own younger siblings than African American girls and thus would quite naturally adopt this role with their older sister's children. Alternately, African American girls might take on more adult kin care tasks (caring for grandparents) and this would limit their time available for niece or nephew care (Burton, 1996). Further longitudinal research is needed to follow siblings across time to answer these questions.

When questioned about their caretaking experiences, most siblings responded that they liked providing care and that they were learning about children and parenting by providing such care. In fact, the more hours of child care provided, the more youth reported learning about children and parenting. Certainly, a supportive and instructive caretaking environment helps to engender positive caretaking experiences (Robertson, Zarit, Duncan, Rovine, & Femia, 2007; Saldana et al., 1999), particularly when children and adolescents are the caretakers. However, as we hypothesized, providing many hours of child care alone (as opposed to in the presence of others) was associated with negative caretaking experiences (more arguing, interfering with one's activities), whereas many hours of caretaking provided in the presence of others was associated with learning benefits and more positive experiences. However, many hours of caretaking provided alone was also associated with some learning benefits, and providing many hours of caretaking in the presence of others was associated with arguing about having to do it and reports that it interfered with one's activities. Across-time trends observed in Study 2 showed that youth reported weaker positive caretaking experiences and stronger negative caretaking experiences from 6 weeks to 6 months postpartum. The newness of the caretaking experience during the very early postpartum weeks may be losing its luster and the harsh reality of how difficult parenting a young infant can be may be settling in (Cowan & Cowan, 2000). There are clearly strong and ongoing negotiations occurring among the teenager, her siblings, and their mother and grandparents as they cope with the extra work brought about by the teen's baby. How youths' caretaking experiences continue to change across time as the baby gets older and the siblings become more used to—and perhaps less interested in over time—their caretaking role is an area for future research. Similarly, qualitative and ethnographic research will be needed to capture many of the dynamics, mechanisms, and cultural models and beliefs about kin care suggested by our survey questions and questionnaires.

Finally, results from Study 2 indicated that youths' caretaking was approximately evenly divided between care provided alone and care done in the presence of others. This suggests that younger siblings do, to some extent, collaborate with others in providing care, with older girls doing so to a larger extent than both younger girls and older boys. The extent of collaborative care also tended to increase across time, suggesting that youths' experiences in family care may develop as a coconstructed, joint family practice in which all family members participate. Group identity theory suggests that participating in daily family routines can help adolescents feel a valued and connected part of the family and serve to consolidate and solidify family values and attitudes (Weisner, Matheson, Coots, & Bernheimer, 2005). Certainly, family caregiving can provide important socialization functions and serve key affilliative needs, particularly for children and adolescents as they learn the nuances of family cooperation and interdependence through the act of caregiving (Bould, 1993; Garey et al., 2002).

Limitations and Directions for Future Study

The limitations of this research should be noted when interpreting its findings. Foremost among them was the reliance on only self-reports of time spent in child care. Youth may over- or underestimate their level of care (Dodson & Dickert, 2004). It is quite likely, for example, that even the hours youth reported underestimate actual coparticipation in care, casual help, watching with others, and so forth. Observational assessments or random time sampling methods (e.g., Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson, 2002) would have helped verify self-reports.

The sample of Study 1 focused only on younger siblings who lived continuously with their teenage sister and her children across a 3-year period. Families in which sibling care is shorter-lived or less continuous (because of the teen, her child, or the sibling moving out of the household) may offer another view of sibling care that was not provided in this study. Perhaps such households are more conflictual and less stable, but such households were not included for study. Furthermore, the eligibility criteria for both studies specified that all families were composed of a mother, a teenage older sister, and an (eligible aged) younger sibling. This necessitated that other family constellations (mother-absent families, families in which a grandparent or other relative is the primary parental figure) were excluded. The eligibility criteria increased comparability for the study, but prevented us from capturing the full diversity and complexity of kin caregiving patterns within families in which teens have babies.

In addition, although the participants in Study 2 were interviewed relatively recently (between 2004 and 2006), the participants in Study 1 were interviewed in the late 1990s. Teenage pregnancy rates have declined significantly since that time and this should be considered in both the interpretation of study findings and in comparisons of findings between studies.

Having shown the salience of sibling care within teenage childbearing families, impacts on the younger sibling would be an important area for further study. For example, previous research has shown that adolescent girls who are highly involved in their teenage sisters' children also want to have a baby as a teenager (East & Jacobson, 2001). Assuming a strong caregiving role within the family then may shape youths' future expectations and aspirations (Call, 1996).

Conclusions

In all, findings from both studies confirm that siblings are a key part of a dynamic and adaptive shared caregiving system within low-income Latino and African American families with teenage parenting daughters. The high frequency of sibling caregiving found in both studies highlights its significance in the family's adaptation to the unique demands of early parenting. Certainly, the findings described here suggest that social scientists need to move beyond the triad of the teen mother, her child, and the child's grandmother as the center of care and instead explore the complex, interdependent network of caregiving within the family. a full understanding of sibling caregiving within these types of families will require both a fuller description and analysis of the roles played by each family member and, more important, of the complex ways in which these roles support and interact with one another to ensure the continued functioning of the family.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grant R01 HD043221 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and grants APR-000970 and APR-006013 from the Office of Population affairs. We thank Beatriz Contreras, Renee Contreras, Emily Horn, and Barbara Reyes for interviewing the study participants.

Contributor Information

Patricia L. East, University of California, San Diego

Thomas S. Weisner, University of California, Los Angeles

Ashley Slonim, Columbia University, New York.

References

- Berk SF. The gender factory: The apportionment of work in American households. New York: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bould S. Familial caretaking: a middle-range definition of family in the context of social policy. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14:133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant BK. Sibling caretaking: Providing emotional support during middle childhood. In: Boer F, Dunn J, editors. Children's sibling relationships: Developmental and clinical issues. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R, DeMent T. Immigration and sociocultural changes in Mexican, Chinese, and Vietnamese American families. In: Booth A, Crouter A, Landale N, editors. Immigration and the family: Research and policy on US immigrants. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 165–200. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Teenage childbearing as an alternative life-course strategy in multigeneration Black families. Human Nature. 1990;1:123–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02692149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Intergenerational patterns of providing care in African American families with teenage childbearers: Emergent patterns in an ethnographic study. In: Bengtson VL, Schaie KW, Burton LM, editors. Adult intergenerational relations: Effects of societal change. New York: Springer; 1995. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Age norms, the timing of family role transitions, and intergenerational caregiving among aging African American women. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:199–208. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. “But what I do does matter”: Adolescent males’ kinwork in low-income urban and rural families; Paper presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence Meetings; San Francisco, CA. 2006. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Child adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations. 2007;56:329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Call KT. The implications of helpfulness for possible selves. In: Mortimer JT, Finch MD, editors. Adolescents, work, and family. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 63–96. [Google Scholar]

- Call KT, Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ. Helpfulness and the development of competence in adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:129–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase ND. Parentification: An overview of theory, research, and society issues. In: Chase ND, editor. Burdened children: Theory, research and treatment of parentification. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Head MR, Bumpus MF, McHale SM. Household chores: Under what conditions do mothers lean on daughters? In: Fuligni AJ, editor. Family obligation and assistance during adolescence: Contextual variations and developmental implications. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson L, Dickert J. Girls' family labor in low-income households: A decade of qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:318–332. [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Racial and ethnic differences in girls' sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Jacobson LJ. The younger siblings of teenage mothers: A follow-up of their pregnancy risk. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:254–264. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Pederson S. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:856–868. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. Burdens and benefits: The impact of early childbearing on the family. Journal of Social Issues. 1980;36:64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, Cooney TM, Call KT. The effects of family characteristics and time use on teenagers' household labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:982–994. [Google Scholar]

- Garey AI, Hansen KV, Hertz R, MacDonald C. Care and kinship. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:703–715. [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow JJ, Lawrence JA. Work contributions to the family: Developing a conceptual and research framework. In: Fuligni AJ, editor. Family obligation and assistance during adolescence: Contextual variations and developmental implications. New York: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2007;56(7):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber J, Spitz E. Sex stratification: Children, housework and jobs. New York: Academic Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kroska A. Investigating gender differences in the meaning of household chores and child care. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:456–473. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Moneta G, Richards MH, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73:1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna I, de Ardon E, Lim Y, Cromwell S, Phillips L, Russell C. The relevance of familism in cross-cultural studies of family caregiving. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1996;18:267–283. doi: 10.1177/019394599601800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. African-American families: Strengths and realities. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, Futrell JA, editors. Resiliency in ethnic minority families: African-American families. Vol. 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1995. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Polatnick MR. Too old for child care? Too young for self care? Negotiating after-school arrangements for middle school. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:728–747. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SM, Zarit SH, Duncan LG, Rovine MJ, Femia EE. Family caregivers' patterns of positive and negative affect. Family Relations. 2007;56:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana DH, Dassori AM, Miller AL. When is caregiving a burden? Listening to Mexican American women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sears HA, Sheppard HM. “I just wanted to be the kid”: Adolescent girls' experiences of having a parent with cancer. Canadian Oncology Journal. 2004;14(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton BA, John D. The division of household labor. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black community. New York: Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB, Burton LM. Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1993;24:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Uttal L. Using kin for child care: Embedment in the socioeconomic networks of extended families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:845–857. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela A. Gender roles and settlement activities among children and their immigrant families. American Behavior Scientist. 1999;42:720–742. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Sibling interdependence and child caretaking: A cross-cultural view. In: Lamb M, Sutton-Smith B, editors. Sibling relationships: Their nature and significance. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1982. pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Socialization for parenthood in sibling caretaking societies. In: Lancaster JB, Altman J, Rossi A, Sherrod L, editors. Parenting across the life span. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1987. pp. 237–270. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS, Garnier H, Loucky J. Domestic tasks, gender egalitarian values, and children's gender typing in conventional and nonconventional families. Sex Roles. 1994;30:23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS, Matheson C, Coots J, Bernheimer LP. Sustainability of daily routines as a family outcome. In: Maynard A, Martini M, editors. Learning in cultural context: Family, peers, and school. New York: Kluwer/Plenum; 2005. pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana R, editor. Understanding Latino families: Scholarship, policy, and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zukow-goldring P. Sibling caregiving. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 253–286. [Google Scholar]