TO THE EDITOR

Discussing preferences for care near the end of life increases the likelihood that patients will receive care consistent with their preferences.1–4 Recent work demonstrates that medical professionals infrequently ask about and document preferences for patients upon hospitalization.5 Since most end-of-life discussions occur in hospitals6, we implemented a quality improvement program incentivizing resident physicians to consistently document key information about inpatient advance care planning discussions in a timely manner in an accessible location.

METHODS

We conducted the project between July 2011 and May 2012 on the medical service at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where the Medical Center and Departments of Medicine and Graduate Medical Education collaborated to form the Housestaff Incentive Program. In this program, trainees choose quality improvement goals and faculty mentor trainee champions through design and implementation of projects. If goals are met, all trainees receive a financial incentive. Internal Medicine residents selected the goal of improving documentation of advance care planning discussions based on pilot work and experience that inconsistent documentation was a barrier to honoring patients’ wishes upon transitions of care. Input from key stakeholders, including emergency department, outpatient, hospital, and palliative care providers informed the intervention, especially location and content of documentation. The project included 3 key elements and the details of each of these are included in the Table. To assess documentation rates, program residents reviewed charts of a random sample of recently discharged patients on a bi-weekly basis. The UCSF Institutional Review Board approved the project.

TABLE. Key Program Elements.

Our intervention included 3 aspects: 1) a discharge summary template, 2), a financial incentive, and 3) staged performance feedback to residents.

| Element | Implementation Month |

|---|---|

| 1. Discharge Summary Template in the Electronic Medical Record | July (Month 1 of Program) |

| We incentivized two template fields: 1) whether the patient expressed wishes for care during the hospitalization, and 2) whether the patient identified a surrogate decision maker. Additional fields allowed residents to enter detailed information | |

| 2. Financial Incentive Program | July (Month 1 of Program) |

| For residents to receive the $400 financial incentive, documentation of the two incentivized fields was required within 48 hours of discharge for 75% of patients in at least 3 of 4 quarters of the year | |

| 3. Audit and Feedback | Varied (See below) |

| General information about the program, including targets and requirements, in monthly reminder emails and at education sessions | July (Month 1 of Program) |

| Feedback at the team level in bi-weekly emails | August (Month 2 of Program) |

| Standardized graphical and tabular data comparing overall, team, and individual residents’ documentation rates in bi-weekly emails | November (Month 5 of Program) |

RESULTS

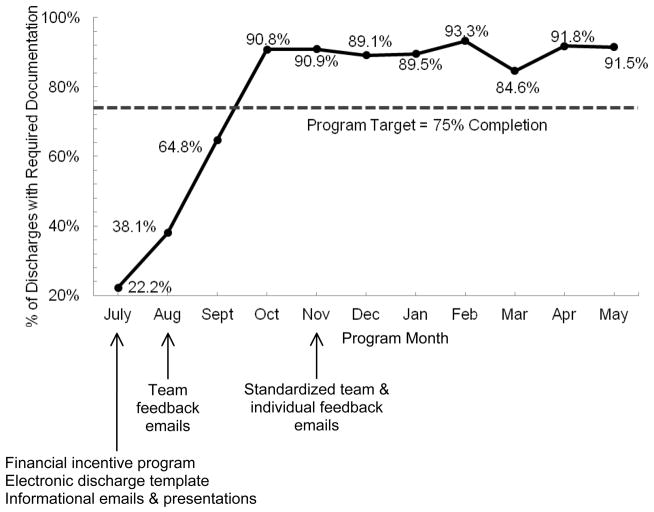

The Figure shows implementation of key aspects of the intervention and the percent of discharge summaries that included the required documentation by project month. Documentation rates are based on chart review of 1474 patients, 55.5% of those discharged from the medical service over the project period. Rates rose from 22.2% at the beginning of the program to over 90% by October and remained near this level through May. In comparison, documentation rates for patients discharged from an attending only service, which used the electronic template but did not receive the financial incentive or feedback, were 0–50% with a yearly average of 11.7%.

FIGURE. Percent of discharge summaries with required documentation of inpatient advance care planning discussions by project month, including when key aspects of the intervention were implemented.

Required documentation, completed within 48 hours of discharge, included whether the patient had expressed wishes for care and whether they identified a surrogate decision maker.

COMMENT

We implemented a multi-faceted intervention to improve resident documentation of advance care planning discussions in a consistent format and location. Over the first few months of the program, rates increased from 22% to greater than 90%, and remained near 90% for the remainder of the year. We believe that the discharge summary template and the financial incentive program provided the foundation for the observed increase in documentation rates. However, rates did not begin to increase until we implemented and refined performance feedback, indicating that this aspect was essential. Further work should be designed to demonstrate which specific interventions are most important.

Several limitations of this project warrant consideration. A key limitation of our project was that we did not measure patient outcomes and doing so will be critical in future work. Additionally, we did not track documentation rates after the end of the project. Future programs should focus on sustainability, for example by EMR automation of audit and feedback. Finally, it is possible that factors other than the intervention contributed to the increase in rates we observed over the course of the program.

In conclusion, our trainee-led quality improvement project, including a structured EMR template, a financial incentive, and performance feedback, increased timely documentation of inpatient advance care planning discussions. Our results highlight the effectiveness of engaging residents in quality improvement activities. Additionally, they present the possibility that such an incentive program could improve patient outcomes, by ensuring that their wishes are available across care transitions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sumant Ranji M.D., Krishan Soni M.D., and Rebecca Sudore M.D., all from UCSF, for their leadership and guidance in managing this program. Additionally, we would like to thank Ari Hoffman M.D., Jeffrey Dixson M.D., Ajay Dharia M.D., YinChong Mak M.D., Christopher Moriates M.D., Kara Bischoff M.D., and Aparna Goel M.D., also all from UCSF, for their work in building and refining this project as well their efforts in generating the required momentum to complete this incentive program.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center and Department of Graduate Medical Education funded this project. The UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute Career Development Program, supported by NIH grant number KL2 RR024130, funded Dr. Anderson. Dr. Lakin presented this work at the Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine on March 15, 2013. All other authors have nothing to disclose. Permission has been obtained by all persons named in this manuscript. Dr. Lakin had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1203–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneiderman JL, Kronick R, Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Langer RD. Effects of offering advance directives on medical treatments and costs. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:599–606. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silveria M, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance Directives and Outcomes of Surrogate Decision Making before Death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:13, 1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to Engage Hospitalized Elderly Patients and Their Families in Advance Care Planning [published online April 1, 2013] JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:204–10. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]