Abstract

Purpose

Dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors are known to increase insulin secretion and beta cell proliferation in rodents. To investigate the effects on human beta cells in vivo, we utilize immunodeficient mice transplanted with human islets. The study goal was to determine the efficacy of alogliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, to enhance human beta cell function and proliferation in an in vivo context using diabetic immunodeficient mice engrafted with human pancreatic islets.

Methods

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic NOD-scid IL2rγnull (NSG) mice were transplanted with adult human islets in three separate trials. Transplanted mice were treated daily by gavage with alogliptin (30 mg/kg/day) or vehicle control. Islet graft function was compared using glucose tolerance tests and non-fasting plasma levels of human insulin and C-peptide; beta cell proliferation was determined by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation.

Results

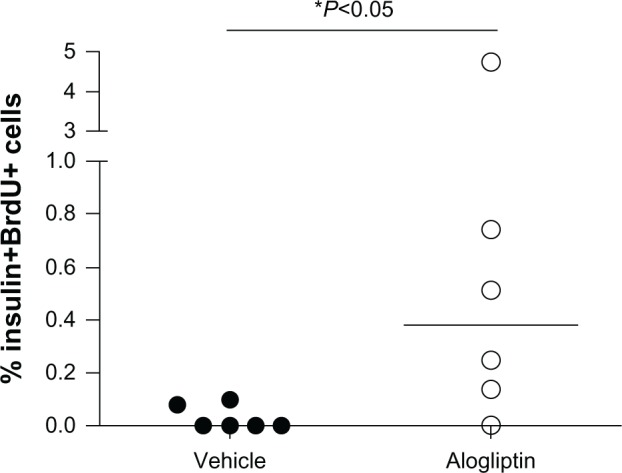

Glucose tolerance tests were significantly improved by alogliptin treatment for mice transplanted with islets from two of the three human islet donors. Islet-engrafted mice treated with alogliptin also had significantly higher plasma levels of human insulin and C-peptide compared to vehicle controls. The percentage of insulin+BrdU+ cells in human islet grafts from alogliptin-treated mice was approximately 10-fold more than from vehicle control mice, consistent with a significant increase in human beta cell proliferation.

Conclusion

Human islet-engrafted immunodeficient mice treated with alogliptin show improved human insulin secretion and beta cell proliferation compared to control mice engrafted with the same donor islets. Immunodeficient mice transplanted with human islets provide a useful model to interrogate potential therapies to improve human islet function and survival in vivo.

Keywords: human islet transplant, DPP-4 inhibitor, glucose tolerance, plasma insulin

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and GLP-1 receptor agonists increase glucosedependent insulin secretion, beta cell viability, and activate proliferative pathways that lead to increased beta cell mass in rodents.1,2 In clinical trials with type 2 diabetic patients, GLP-1 receptor agonists lowered both fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations,3,4 although no improvement (as measured by C-peptide secretion) was observed in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes.5 Glycemic control of patients taking metformin or sulfonylurea was also improved in conjunction with GLP-1 receptor agonists.6–8 In clinical trials with agents that block GLP-1 degradation, such as dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, fasting and postprandial glucose levels of patients are also lowered, consistent with improved pancreatic beta cell function.9–11 However, human islet function remains difficult to assess directly due to inaccessibility of relevant tissues, as well as inherent variability between patients. An alternative method to investigate human islet function in vivo is to transplant human islets into streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic NOD-scid IL2rγnull (NSG) mice.12,13

Recently, a new DPP-4 inhibitor, alogliptin, has been developed14 and its safety and efficacy in treating type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients is being investigated.15–17 Alogliptin was found to improve glycemic control in patients with poorly controlled diabetes as evidenced by reduced fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels.17 We hypothesized that alogliptin treatment of diabetic immunodeficient mice engrafted with human islets will measurably enhance the proliferation and insulin secretory function of human beta cells in an in vivo setting. The goal of this study was to utilize STZ-induced diabetic NSG mice transplanted with human pancreatic islets to determine the ability of alogliptin to enhance human beta cell function and proliferation.

Material and methods

Mice and diabetes induction

NOD.cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (abbreviated as NOD-scid IL2rγnull or NSG) mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility and maintained12 in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School; the NSG is an immunodeficient mouse that can be engrafted with functional human cells and tissues for in vivo studies.18

Male NSG mice (8–12 weeks old) received a single intraperitoneal injection of 160 mg/kg STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MI, USA) to induce diabetes (blood glucose >300 mg/dL on two consecutive days). Blood glucose was monitored with an ACCU-CHEK Aviva Plus glucometer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IL, USA). After diabetes was confirmed, mice were given insulin implants (LinShin Canada, Inc, Toronto, ON, Canada) until human islets were available for transplant.

Human islet transplantation

Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Insulin implants were removed upon transplant of 2000 human islet equivalents (IEQs). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized and prepared for surgery. The skin and muscle layer over the spleen was incised, and the kidney was gently externalized with forceps. The human islets (suspended in Connaught Medical Research Laboratories plus 1% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) were injected into the subrenal capsular space using a SURFLO winged infusion set (23 g × 3/4 inch; Terumo Medical Corporation, Somerset, NJ, USA). The kidney was then replaced in the abdominal cavity, the muscle was sutured, and the skin was closed with an Autoclip wound closure system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX, USA).

Alogliptin treatment

One day post-transplant, diabetic mice that received islets from a single donor were randomized into two groups of five mice each and treated daily by oral gavage with 30 mg/kg/day alogliptin (provided by Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Deerfield, IL, USA) or equivalent volume of vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). The 30 mg/kg/day dosage is mid-range between doses (15 and 45 mg/kg) that have previously been shown to be effective in restoring beta cell mass and islet function in two different mouse models of diabetes.19,20 Daily treatments were continued until graft removal at 32–39 days post-transplant.

Glucose tolerance test

Mice were fasted overnight and blood glucose was measured following intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2.0 g/kg body weight). Glucose area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by the trapezoidal rule.

Human insulin and C-peptide analysis

Heparinized blood from nonfasting mice was collected with protease inhibitor (aprotinin; Sigma-Aldrich) at 3–4 weeks post-transplant; plasma was stored at −80°C until analyzed by human-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH, USA).

Bromodeoxyuridine treatment, histology, and immunofluorescence staining

Human islet-engrafted mice were provided drinking water containing 0.8 mg/mL of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) ad libitum for 7 days prior to recovery of the graft-bearing kidney. Islet graft-bearing kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Paraffin-embedded sections were dualstained with guinea pig anti-insulin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and rat anti-BrdU (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NJ, USA); secondary Alexa-Fluor and Cy-5 antibodies and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Insulin+ and insulin+BrdU+ cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, New York, NY, USA); counts were performed with MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA, USA).

Statistical analyses

Time-course data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc test; remaining data were analyzed with Mann-Whitney or t-test as appropriate (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA, USA). P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

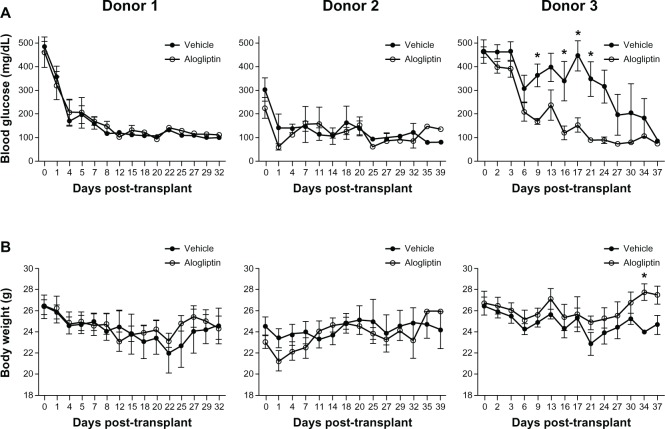

Normoglycemic NSG mice (blood glucose <150 mg/dL) were made chemically diabetic with STZ treatment. After diabetes was confirmed, mice were given subcutaneous insulin implants to maintain the health of the animals until human islets were available for transplant. Three independent studies were performed with human islets from three different donors. The islet donor characteristics are shown in Table 1. Daily alogliptin (or vehicle control) treatments were started at day 1 post-transplant. Normoglycemia was restored within 1 week for diabetic mice transplanted with 2000 IEQs from both Donors 1 and 2, regardless of treatment status (Figure 1A). In contrast, mice transplanted with 2000 IEQs from Donor 3 and treated with alogliptin showed a significant acceleration in the lowering of blood glucose levels relative to mice receiving vehicle alone. At the end of the study period, all mice in all groups were normoglycemic. As expected, the body weights (Figure 1B) of alogliptintreated mice transplanted with Donor 3 islets significantly improved compared to the vehicle control mice.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of human islet donors

| Donor 1 | Donor 2 | Donor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 51 | 53 | 65 |

| Sex (M/F) | F | nr | M |

| Body weight, kg | 69.0 | nr | nr |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 | 27.3 | 24.5 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; F, female; M, male; nr, not recorded.

Figure 1.

Comparison of blood glucose and body weights of control and alogliptin-treated mice engrafted with human islets.

Notes: Diabetic NSG mice were transplanted with human islets from three individual donors and treated daily by gavage with alogliptin (n=5, each donor) or vehicle control (n=5, each donor). (A) Blood glucose and (B) body weight of the mice were monitored over the treatment period on the days indicated; shown are mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: NSG, NOD-scid IL2rγnull.

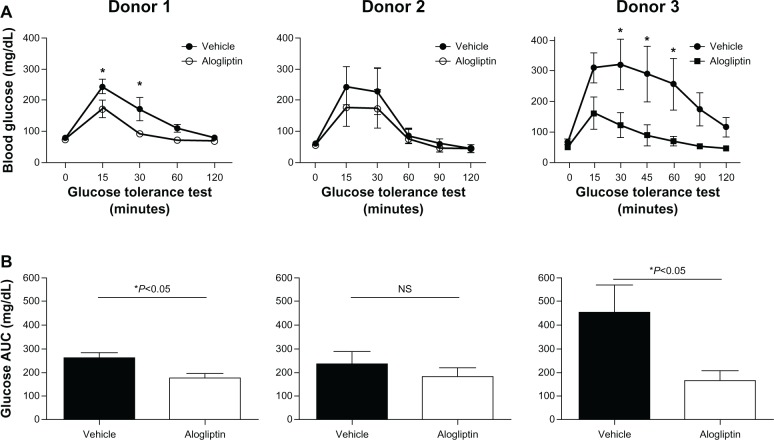

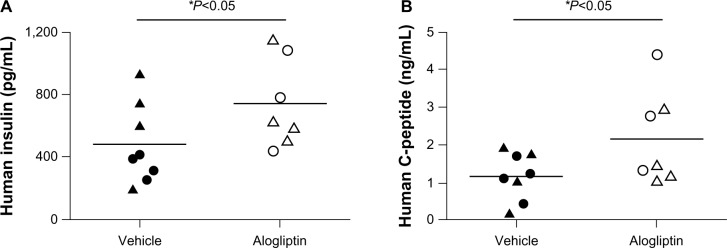

Daily alogliptin treatment also significantly improved glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) in mice engrafted with islets from two of the three human donors (Figure 2A); this was also demonstrated with glucose AUC measurements (Figure 2B). Consistent with improved GTTs, the non-fasting plasma levels of both human insulin (Figure 3A) and C-peptide (Figure 3B) were significantly higher in islet-engrafted mice treated with alogliptin compared to vehicle-treated mice. When comparing individual donors, human insulin and C-peptide values following alogliptin treatment were similar between Donors 2 and 3, consistent with the recipient mice blood glucose levels (mean =89 and 82 mg/dL, respectively) obtained at the time of analysis. Interestingly, although blood glucose levels were higher in control mice engrafted with islets from Donor 3 (mean =198 mg/dL) than from Donor 2 (mean =87 mg/dL), human insulin values from Donor 3 engrafted mice were somewhat elevated compared to Donor 2 (Figure 3A), whereas C-peptide levels were similar (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Comparison of glucose tolerance tests in control and alogliptin-treated mice engrafted with human islets.

Notes: Human islet engrafted mice were treated daily with alogliptin or vehicle control. (A) A glucose tolerance test was administered to mice engrafted with islets from Donors 1 and 2 at days 21 and 19, respectively, following islet transplantation. The glucose tolerance test on mice engrafted with Donor 3 islets was administered at day 31 when the blood glucose of vehicle control mice was approaching normoglycemia. *P<0.05. (B) Glucose AUC for the 120 min glucose tolerance test shown in (A); n=4 mice per group for each donor; shown are mean ± standard error of the mean.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; NS, not significant.

Figure 3.

Comparison of human insulin and C-peptide levels in control and alogliptin-treated mice engrafted with human islets.

Notes: Non-fasting blood was collected from NSG mice engrafted with human islets from Donors 2 and 3 on days 26 and 24, respectively, following transplant. Plasma levels of (A) human insulin and (B) human C-peptide from individual vehicle control (n=8 total, 4 per islet donor) or alogliptin-treated (n=7 total, 4 from Donor 2, and 3 from Donor 3) mice are shown. Plasma samples from mice engrafted with islets from Donor 1 were not available for analysis. Each dot or triangle represents data obtained from an individual mouse engrafted with human islets from Donors 2 or 3, respectively; horizontal bar indicates the mean for each group.

Abbreviation: NSG, NOD-scid IL2rγnull.

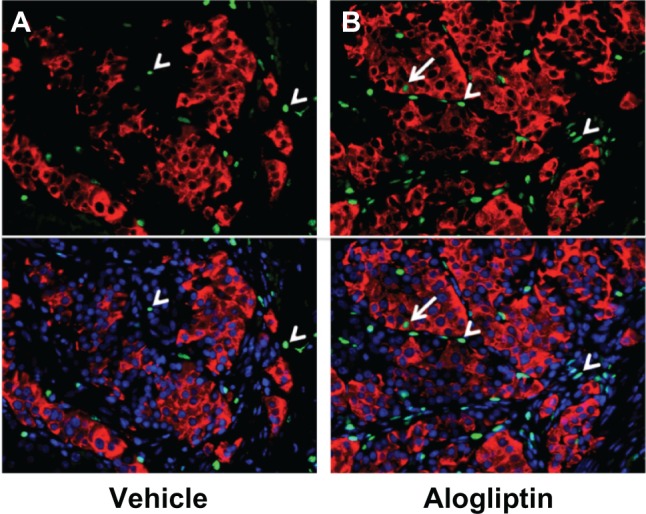

To determine whether alogliptin treatment enhances beta cell proliferation within the human islet grafts, the mice were supplied with BrdU in their drinking water. Upon surgical removal of the graft-bearing kidney all mice became acutely hyperglycemic (blood glucose >500 mg/dL), thus documenting that the human islet graft was responsible for maintaining normoglycemia. The recovered islet grafts were subsequently immunostained for insulin and BrdU. Immunofluorescent analysis of human islet grafts from all three donors demonstrated that the percentage of insulin+BrdU+ cells from alogliptin-treated mice was significantly higher than from vehicle control mice (Figure 4). Representative islet graft sections from a vehicle control and an alogliptin-treated mouse engrafted with islets from Donor 1 are shown in Figure 5A and B, respectively. Although BrdU+ staining indicative of proliferating cells was readily detectable in all islet graft sections (Figure 5A), only two of six human islet grafts analyzed from control mice (one each from Donors 1 and 3) had any detectable insulin+BrdU+ cells. In contrast, insulin+BrdU+ cells (Figure 5B) were present in five of six islet grafts analyzed (from all three human islet donors) in alogliptin-treated mice. When totaled, the average proliferation of human beta cells in all islet grafts analyzed from alogliptin-treated mice was 0.58% (44 of 7591 insulin+ cells), a 10-fold increase from that observed in islet grafts from vehicle control mice (0.056%, 2 of 3542 insulin+ cells).

Figure 4.

Induction of human beta cell proliferation with alogliptin treatment of islet engrafted mice. Percent human beta cell proliferation in islet grafts from vehicle control (n=6 total, 2 per islet donor) and alogliptin-treated (n=6 total) mice.

Note: Each dot represents data obtained from a single islet graft from one mouse.

Abbreviation: BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine.

Figure 5.

Insulin+BrdU+ beta cells in human islet grafts from alogliptin-treated mice.

Notes: Representative micrographs of human islets from a single donor (Donor 1) engrafted in (A) vehicle control or (B) alogliptin-treated mice are shown. Top panels show insulin (red) and BrdU (green) staining; bottom panels include nuclei staining with DAPI (blue). Similar results were seen with islet grafts from Donors 2 and 3. Arrows show insulin+BrdU+ cells; arrowheads indicate insulin-negative BrdU+ cells; cells were only counted as insulin+ if the staining was visible around the entire perimeter of the nucleus.

Abbreviations: BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Discussion

This study investigated the therapeutic efficacy of alogliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, on human beta cell function and proliferation in diabetic immunodeficient NSG mice engrafted with adult human islets. Because multiple cohorts of mice can be transplanted with islets from a single human donor, donor-specific beta cell function can be compared directly in islet-engrafted control and treated mice, thus eliminating variability in donor-to-donor islet isolation and handling, as well as differences due to age, sex, body mass index (BMI), lifestyle, or pre-existing disease. In this study, we utilized human islets derived from both male and female islet donors, aged 51–65 years, with BMI between 24–28. Here we report significant beneficial effects of alogliptin on human beta cell proliferation, circulating levels of human insulin and C-peptide, and glucose homeostasis of NSG mice transplanted with adult human islets.

A recent study in a mouse model of diabetes demonstrated similar beneficial effects of alogliptin to lower fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels in diabetic mice.19 This study also demonstrated an improvement in beta cell mass and insulin content in pancreata of alogliptin-treated mice.19 Recently, alogliptin in combination with pioglitazone has been reported to enhance regeneration of transplanted syngeneic mouse islets and endogenous islets of STZ-diabetic mice.20 Although informative, such studies on mouse beta cells may not accurately predict human beta cell responses due to differences in the architecture, signaling pathways, and relative proportions of endocrine cells, as well as beta cell proliferative capacity which is robust in young rodents but negligible in humans, especially in individuals >30 years old.21,22

To circumvent potential discrepancies in therapeutic outcome due to species differences, we utilized diabetic NSG mice engrafted with human islets. We observed improved glucose tolerance tests in alogliptin-treated versus control mice transplanted with human islets from two of three individual donors (including 65-year-old Donor 3). Because our immunodeficient mice are exposed to the same diet and housing conditions, we can effectively exclude the potential contribution of such factors to glucose homeostasis and suggest that alogliptin treatment directly enhances human islet function.

Indeed, the improved glucose tolerance in human islet engrafted mice treated with alogliptin is consistent with our finding that plasma levels of human insulin and C-peptide were also significantly increased in these alogliptin-treated mice. We observed a 1.5-fold increase in human insulin (742±106 versus 483±91 pg/mL) and a 1.8-fold increase in human C-peptide (2.17±0.47 versus 1.18±0.22 ng/mL) in alogliptin-treated versus control mice. This is strikingly consistent with data from obese diabetic ob/ob mice, where 4 weeks of treatment with alogliptin increased plasma insulin by 1.5–2.0 fold.23 Similar results were also reported in T2D patients, in whom the homeostasis model assessment of beta-cell function (HOMA-B) worsened with placebo, but improved with alogliptin treatment.17

In rodents, DPP-4 inhibitors were reported to increase the proliferation of beta cells.1,2,24 In our study, alogliptin treatment also stimulated human beta cell proliferation within the islet grafts by approximately 10-fold, a similar magnitude of induction that we and others have reported for engrafted human beta cells in response to hyperglycemia.25,26 Together these data may suggest that human beta cells, even from older individuals, can be induced to proliferate in vivo in response to certain inductive stimuli, albeit at a much lower level than observed in rodents. Nonetheless, the small numbers of proliferating beta cells cannot account for the significant increase in plasma levels of human insulin and improved glucose tolerance tests we observed. Speculatively, however, longer-term alogliptin treatment in patients with T2D may result in a small, but functionally relevant enhancement of human beta cell mass that may add to other ameliorative effects of alogliptin on islet function and survival to improve the total therapeutic benefit.

Conclusion

In this study we demonstrate that human islet-engrafted NSG mice treated with alogliptin show improved glucose tolerance and increased human insulin secretion and beta cell proliferation compared to islet-engrafted control mice. Thus, immunodeficient mice transplanted with human islets provide a useful model to interrogate potential therapies to improve human islet function and survival in an in vivo setting without putting patients at risk. In addition, the ability to transplant multiple mice with human islets from a single donor provides a powerful experimental paradigm to assess potential mechanisms at play, which is limited in clinical studies with human patients.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program. We thank Linda Paquin for outstanding technical support.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptides: regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(2):161–171. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan JM, Bulotta A, Hui H, Perfetti R. GLP-1 receptor agonists are growth and differentiation factors for pancreatic islet beta cells. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19(2):115–123. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D, MacConell L, Zhuang D, et al. Effects of once-weekly dosing of a long-acting release formulation of exenatide on glucose control and body weight in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1487–1493. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilsbøll T, Zdravkovic M, Le-Thi T, et al. Liraglutide, a long-acting human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, given as monotherapy significantly improves glycemic control and lowers body weight without risk of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1608–1610. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rother KI, Spain LM, Wesley RA, et al. Effects of exenatide alone and in combination with daclizumab on beta-cell function in long-standing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2251–2257. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD, Exenatide-113 Clinical Study Group Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2628–2635. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1092–1100. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendall DM, Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1083–1091. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters A. Incretin-based therapies: review of current clinical trial data. Am J Med. 2010;123(Suppl 3):S28–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman GA, Stein PP, Thornberry NA, Wagner JA. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: focus on sitagliptin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81(5):761–767. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aschner P, Kipnes MS, Lunceford JK, Sanchez M, Mickel C, Williams-Herman DE, Sitagliptin Study 021 Group Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(12):2632–2637. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(10):6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(2):118–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng J, Zhang Z, Wallace MB, et al. Discovery of alogliptin: a potent, selective, bioavailable, and efficacious inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J Med Chem. 2007;50(10):2297–2300. doi: 10.1021/jm070104l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andukuri R, Drincic A, Rendell M. Alogliptin: a new addition to the class of DPP-4 inhibitors. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2009;2:117–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott LJ. Alogliptin: a review of its use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2010;70(15):2051–2072. doi: 10.2165/11205080-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeFronzo RA, Fleck PR, Wilson CA, Mekki Q, Alogliptin Study 010 Group Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor alogliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2315–2317. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brehm MA, Shultz LD, Greiner DL. Humanized mouse models to study human diseases. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(2):120–125. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328337282f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Wang Z, Huang Y, Wang J. Effects of chronic administration of alogliptin on the development of diabetes and β-cell function in high fat diet/streptozotocin diabetic mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(4):337–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin H, Park SY, Wang XJ, et al. Enhancing pancreatic Beta-cell regeneration in vivo with pioglitazone and alogliptin. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brissova M, Fowler MJ, Nicholson WE, et al. Assessment of human pancreatic islet architecture and composition by laser scanning confocal microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53(9):1087–1097. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5C6684.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perl S, Kushner JA, Buchholz BA, et al. Significant human beta-cell turnover is limited to the first three decades of life as determined by in vivo thymidine analog incorporation and radiocarbon dating. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(10):E234–E239. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moritoh Y, Takeuchi K, Asakawa T, Kataoka O, Odaka H. Chronic administration of alogliptin, a novel, potent, and highly selective dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, improves glycemic control and beta-cell function in obese diabetic ob/ob mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;588(2–3):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inaba W, Mizukami H, Kamata K, Takahashi K, Tsuboi K, Yagihashi S. Effects of long-term treatment with the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor vildagliptin on islet endocrine cells in non-obese type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;691(1–3):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitt HE, Cyphert TJ, Pascoe JL, et al. Glucose stimulates human beta cell replication in vivo in islets transplanted into NOD-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54(3):572–582. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1919-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diiorio P, Jurczyk A, Yang C, et al. Hyperglycemia-induced proliferation of adult human beta cells engrafted into spontaneously diabetic immunodeficient NOD-Rag1null IL2rγnull Ins2 Akita mice. Pancreas. 2011;40(7):1147–1149. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821ffabe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]