Abstract

Objectives. We investigated trends in the educational gradient of US adult mortality, which has increased at the national level since the mid-1980s, within US regions.

Methods. We used data from the 1986–2006 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File on non-Hispanic White and Black adults aged 45 to 84 years (n = 498 517). We examined trends in the gradient within 4 US regions by race–gender subgroup by using age-standardized death rates.

Results. Trends in the gradient exhibited a few subtle regional differences. Among women, the gradient was often narrowest in the Northeast. The region’s distinction grew over time mainly because low-educated women in the Northeast did not experience a significant increase in mortality like their counterparts in other regions (particularly for White women). Among White men, the gradient narrowed to a small degree in the West.

Conclusions. The subtle regional differences indicate that geographic context can accentuate or suppress trends in the gradient. Studies of smaller areas may provide insights into the specific contextual characteristics (e.g., state tax policies) that have shaped the trends, and thus help explain and reverse the widening mortality disparities among US adults.

The inverse association between education level and mortality risk in the United States is pervasive and enduring.1–3 Education provides numerous resources that tend to lower mortality, including higher incomes, stable employment, social ties, health-promoting behaviors, a sense of personal control, and safe neighborhoods.4 The educational gradient in mortality has been a long-standing concern of researchers, policymakers, and public health organizations.5,6

Despite initiatives such as Healthy People to reduce mortality disparities,6 the gradient has increased over the past half-century.7–13 The pace and size of the increase has varied across population subgroups. For example, the gradient grew during the 1960s and 1970s more among White men than women.8,11,13 Since the mid-1980s it seems to have grown more among women than men.14,15 Among non-Hispanic White and Black women, this recent growth reflected declining mortality among the higher-educated alongside increasing mortality among the low-educated.14,15 Among their male peers, the recent growth reflected declining mortality across education levels, with the higher-educated experiencing the largest declines.14,15

The reasons for the increasing gradient are poorly understood. Studies investigating the reasons have largely focused on national trends in causes of death by education level.14,16–18 They have found that smoking-related causes played an important role, especially among women. Though informative, those studies have drawn attention to individual-level behavioral explanations. A complete explanation must incorporate contextual factors that lie upstream in the causal chain,19 such as economic and geographic contexts. In other words, the search for explanations may benefit by moving away from methodological individualism (the notion that mortality inequalities can be explained exclusively by individual characteristics) and toward an approach that integrates the broader contexts that constrain individuals’ lives.20

The contextual factor of interest in this study is geographic area. It is important to investigate geographic variation in how the gradient has changed because it can shed light on the causes of the trends. If the gradient widened (or narrowed) in certain geographic areas, this suggests that characteristics unique to those areas—for example, economic policy or social welfare—played an important role. If the gradient widened similarly across areas, this suggests that the underlying causes transcend areal characteristics. In addition, examining trends in the gradient within areas helps decouple contextual and compositional explanations. For instance, the mortality increase among low-educated women at the national level could simply reflect a growing proportion of low-educated women from high-mortality areas of the Deep South.

Although previous studies have not examined whether geographic context shapes trends in the gradient, they have shown that geographic context shapes mortality, net of individual factors,21–28 and mortality trends.22,26,29,30 For instance, during the 1980s and 1990s, gains in life expectancy occurred mainly in the Northeast and West coast, and declines occurred mainly in the Deep South, in Appalachia, along the Mississippi River, and in parts of the Midwest and Texas.22

Explanations for the geographic pattern in mortality trends remain elusive. The salient features of geographic context and their pathways to health are complex, although material infrastructure and collective social functioning are especially important.24,25,31–34 Ezzati et al.22 found that county-level gains in life expectancy were positively related to county-level income but not to the Gini coefficient or the percentage completing high school. Murray et al.26 found that life expectancy gaps among 8 geographic areas could not be explained by race, income, or health care access and utilization. Despite these informative comparisons of mortality trends across areas, it remains unclear whether morality disparities have changed within areas.

The geographic areas we examined in this study are the 4 US regions: Northeast, North Central and Midwest (hereafter Midwest), South, and West.35 The Census Bureau defines regions on the basis of historical development, economic structures, political systems, topography, population composition, and other factors.35 Regions also differ in educational development and levels. The West was a leader in the secondary education movement whereas the South has trailed behind.36 Regional variation in economic characteristics has also emerged and may have shaped mortality disparities. For instance, whereas the Northeast has increasingly had the most progressive tax policies, the South and more recently the West have implemented regressive policies that disproportionately hurt the poor and elevate mortality.37 The Northeast has also emerged as the region with the highest social expenditures per capita.37 Creative occupations have become concentrated in the Northeast and West.38 Cigarette prices have risen most sharply in the Northeast and West.39 Because of the large variation in regional characteristics, and the spatial clustering of mortality trends, it is important to examine the gradient within regions.

In this study, we addressed the following questions among US adults aged 45 to 84 years in 1986 through 2006: (1) To what extent has the educational gradient of mortality changed over time within regions?; (2) Do any regions exhibit especially wide or narrow gradients and has this changed over time?; and (3) To what extent has the increase in low-educated women’s mortality occurred across regions? Then we explored what the patterns imply about the causes of the widening gradient.

METHODS

We used the public-use National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File (NHIS-LMF) downloaded from the Minnesota Population Center.40 It links adults in the 1986 through 2004 annual cross-sectional waves of the NHIS with death records in the National Death Index through December 31, 2006. The link is mainly based on a probabilistic matching algorithm, which correctly classifies the vital status of 98.5% of eligible survey records.41 Two strengths of the NHIS-LMF are that its education data are self-reported and available earlier than in the vital statistics. Self-reported education appears to be more accurate than education data on death certificates.42 The NHIS-LMF starts in 1986; the standard US death certificate included an item about education in 1989 but completion rates did not reach 80% for many years.42

We focused on non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks to minimize the potential for education to have been obtained abroad. We selected adults aged 25 to 84 years at interview to ensure that most were old enough to have completed their education through a bachelor’s degree and to account for the top-coding of ages at 85 years starting in 1997. We created a person-year file by aging respondents by 1 year starting with their interview year and ending with their year of death or 2006 if they survived. We then retained person-year observations for our age range of interest, 45 to 84 years. We set the lower limit at 45 because there are few deaths to those aged younger than 45 years in the NHIS-LMF and because ages 25 to 44 years contributed little to the widening gradient during this period14; we set the upper limit at 84 because mortality matches are less reliable among older women.43

Region, Education, and Time

We investigated trends in the gradient within 4 US regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.35 In addition to the substantive reasons for examining these regions, regional analyses minimize migration effects (e.g., individuals have historically been about half as likely to move regions than states in a given year)44 and circumvent complexities in classifying adults who live and work in different states or counties. However, there is no consensus about which geographic level to use to track health inequalities.45 Each level has strengths and weaknesses. The main downside of regional analyses is that they, like national analyses, may mask heterogeneity across states and counties. A full understanding of trends in the gradient requires investigating multiple geographic levels.

In defining time and education, our goal was to assess as many categories as possible but to ensure that each contained enough observations to estimate reliable death rates. For Whites, we examined 4 periods (1986–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001, and 2002–2006) and 4 education levels (0–11 years, high-school credential, some college or associate’s degree, and bachelor’s degree or higher). Because of the smaller sample of Black respondents, we collapsed time periods and education levels to obtain reliable rates. We examined 2 periods (1986–1996 and 1997–2006) and 3 education levels (0–11 years, high-school credential, and some college or higher).

Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows the number of person-years and deaths in our sample by region, period, and education. The total sample contained 230 710 White women who experienced 42 436 deaths during the follow-up, 199 904 White men with 50 690 deaths, 39 896 Black women with 9265 deaths, and 28 007 Black men with 9128 deaths. The table also shows the education distribution within regions. As expected, education levels were lowest in the South and highest in the West.36 For example, during 2002–2006, 16% of White women aged 45 to 84 years in the South had 0 to 11 years of education versus 8% in the West and 12% in other regions.

Analysis

For each region, we estimated death rates by education level within each period. The rates were standardized to the age and education distribution of the 2000 US population of non-Hispanic White women by 10-year age groups (45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84) with data from the Current Population Survey.46 We then used the standardized rates to calculate absolute and relative measures of the gradient within each period. The standardized rate difference (SRD) is the absolute difference between the death rate of adults with 0 to 11 years of education and adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher (among Whites) or adults with at least some college education (among Blacks). The standardized rate ratio (SRR) is the ratio of the 2 rates.

We examined trends in the gradient by plotting the age-standardized death rates across periods. For Whites, we also tested for linear trends in the SRD and ln(SRR) by regressing each measure on period using ordinary least squares to obtain the P value for period.18,47 The x-values for the 4 periods were −8.0, −2.5, 2.5, and 7.5. Trends with P < .05 are statistically significant. We did not formally test trends among Blacks because their trends were based on 2 data points.

Our third research question focused on low-educated women. Here, we dichotomized education into 0 to 11 years versus 12 years or more. We first tested whether mortality trends of low-educated women differed from other women by estimating the ln(odds) of death from age (time varying from 45 to 84 years), period, education, and an education-by-period interaction. A significant and positive interaction indicates the mortality gap widened over time. We then tested whether the mortality of low-educated women increased over time by estimating the ln(odds) of death from age and period among the subset of low-educated women. We stratified all models by region, gender, and race; weighted them with the eligibility-adjusted sample weights; adjusted them for survey design; and estimated with PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We addressed each of our 3 research questions in turn. First, we examined the extent to which the educational gradient of mortality changed within each US region across 1986 through 2006 by race–gender subgroup.

Changes in the Educational Gradient of Mortality by Time and Region

Non-Hispanic Whites.

The age-standardized death rates for Whites are listed in Table 1. The trends for the United States corroborate previous studies. Death rates among women with 0 to 11 years of education increased over time (e.g., from 2350 deaths per 100 000 women in 1986–1991 to 2840 deaths per 100 000 women in 2002–2006), remained steady among women with a high-school credential or some college, and declined slightly among college-educated women. Tests for linear trends in the absolute and relative gradients indicate that between 1986–1991 and 2002–2006 the SRD significantly grew from 1691 to 2249 deaths per 100 000 women (P = .002) and the SRR significantly grew from 3.55 to 4.82 (P = .035). Among men, death rates declined for all education levels. The SRD remained stable but the SRR significantly grew from 3.84 to 4.57 (P = .030).

TABLE 1—

Age-Standardized Death Rates, Standardized Rate Differences, and Standardized Rate Ratios Across Time and Education Level Among White Women and Men Aged 45–84 Years: 1986–2006 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File

| Education Level,a

Death Rate |

||||||

| Region and Time | 0–11 Years | HS | SC | CO | SRDa | SRRa |

| White women | ||||||

| United States | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0235 | 0.0133 | 0.0088 | 0.0066 | 1691 | 3.55 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0255 | 0.0133 | 0.0097 | 0.0069 | 1858 | 3.69 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0270 | 0.0140 | 0.0097 | 0.0065 | 2046 | 4.14 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0284 | 0.0136 | 0.0092 | 0.0059 | 2249 | 4.82 |

| P for trend | .002 | .035 | ||||

| Northeast | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0232 | 0.0135 | 0.0082 | 0.0071 | 1614 | 3.28 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0251 | 0.0134 | 0.0095 | 0.0062 | 1898 | 4.08 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0253 | 0.0132 | 0.0092 | 0.0056 | 1977 | 4.55 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0259 | 0.0132 | 0.0086 | 0.0053 | 2066 | 4.91 |

| P for trend | .045 | .023 | ||||

| Midwest | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0242 | 0.0130 | 0.0101 | 0.0070 | 1716 | 3.44 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0245 | 0.0130 | 0.0101 | 0.0070 | 1748 | 3.50 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0281 | 0.0138 | 0.0091 | 0.0068 | 2121 | 4.10 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0279 | 0.0133 | 0.0083 | 0.0057 | 2213 | 4.86 |

| P for trend | .058 | .051 | ||||

| South | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0231 | 0.0132 | 0.0078 | 0.0062 | 1684 | 3.71 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0268 | 0.0127 | 0.0101 | 0.0071 | 1968 | 3.77 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0269 | 0.0146 | 0.0098 | 0.0073 | 1962 | 3.68 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0301 | 0.0140 | 0.0096 | 0.0066 | 2349 | 4.58 |

| P for trend | .059 | .256 | ||||

| West | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0239 | 0.0138 | 0.0092 | 0.0064 | 1743 | 3.70 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0243 | 0.0146 | 0.0091 | 0.0073 | 1696 | 3.31 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0278 | 0.0147 | 0.0105 | 0.0061 | 2169 | 4.58 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0285 | 0.0140 | 0.0099 | 0.0057 | 2277 | 4.99 |

| P for trend | .098 | .177 | ||||

| White men | ||||||

| United States | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0436 | 0.0236 | 0.0160 | 0.0113 | 3223 | 3.84 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0418 | 0.0238 | 0.0167 | 0.0107 | 3115 | 3.92 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0416 | 0.0225 | 0.0160 | 0.0098 | 3188 | 4.27 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0403 | 0.0212 | 0.0153 | 0.0088 | 3144 | 4.57 |

| P for trend | .546 | .03 | ||||

| Northeast | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0403 | 0.0244 | 0.0179 | 0.0119 | 2842 | 3.38 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0416 | 0.0238 | 0.0171 | 0.0102 | 3142 | 4.08 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0428 | 0.0212 | 0.0160 | 0.0089 | 3386 | 4.80 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0373 | 0.0197 | 0.0143 | 0.0084 | 2890 | 4.44 |

| P for trend | .785 | .152 | ||||

| Midwest | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0420 | 0.0223 | 0.0146 | 0.0118 | 3017 | 3.55 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0407 | 0.0222 | 0.0164 | 0.0106 | 3011 | 3.85 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0383 | 0.0226 | 0.0148 | 0.0100 | 2833 | 3.84 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0388 | 0.0202 | 0.0152 | 0.0085 | 3035 | 4.58 |

| P for trend | .826 | .087 | ||||

| South | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0467 | 0.0251 | 0.0154 | 0.0126 | 3417 | 3.72 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0434 | 0.0254 | 0.0180 | 0.0117 | 3172 | 3.72 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0442 | 0.0236 | 0.0168 | 0.0105 | 3369 | 4.22 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0436 | 0.0234 | 0.0167 | 0.0097 | 3393 | 4.51 |

| P for trend | .876 | .06 | ||||

| West | ||||||

| 1986–1991 | 0.0446 | 0.0223 | 0.0166 | 0.0088 | 3583 | 5.08 |

| 1992–1996 | 0.0402 | 0.0241 | 0.0153 | 0.0100 | 3017 | 4.02 |

| 1997–2001 | 0.0388 | 0.0224 | 0.0161 | 0.0094 | 2938 | 4.12 |

| 2002–2006 | 0.0383 | 0.0215 | 0.0144 | 0.0083 | 2992 | 4.59 |

| P for trend | .194 | .637 | ||||

Note. CO = bachelor’s degree or higher; HS = high-school credential; SC = some college or associate’s degree; SRD = standardized rate difference; SRR = standardized rate ratio.

The SRD is the difference (and the SRR the ratio) of the death rate for 0 to 11 years of education vs a bachelor’s degree or higher, per 100 000 adults.

The death rates by region are also shown in Table 1. Among women, the linear increase in the SRD was statistically significant in the Northeast (P < .05) and approached significance in other regions (P < .1). Because the trend test is based on 4 data points, P < .1 is meaningful. The SRR significantly grew in the Northeast and Midwest during the study; it began to grow toward the end of the study in the West and South. Among men, the SRD was fairly stable in all regions (P > .1), although it shrunk in the West after the first period. The SRR was also fairly stable within all regions, although it marginally increased in the Midwest and South (P < .1).

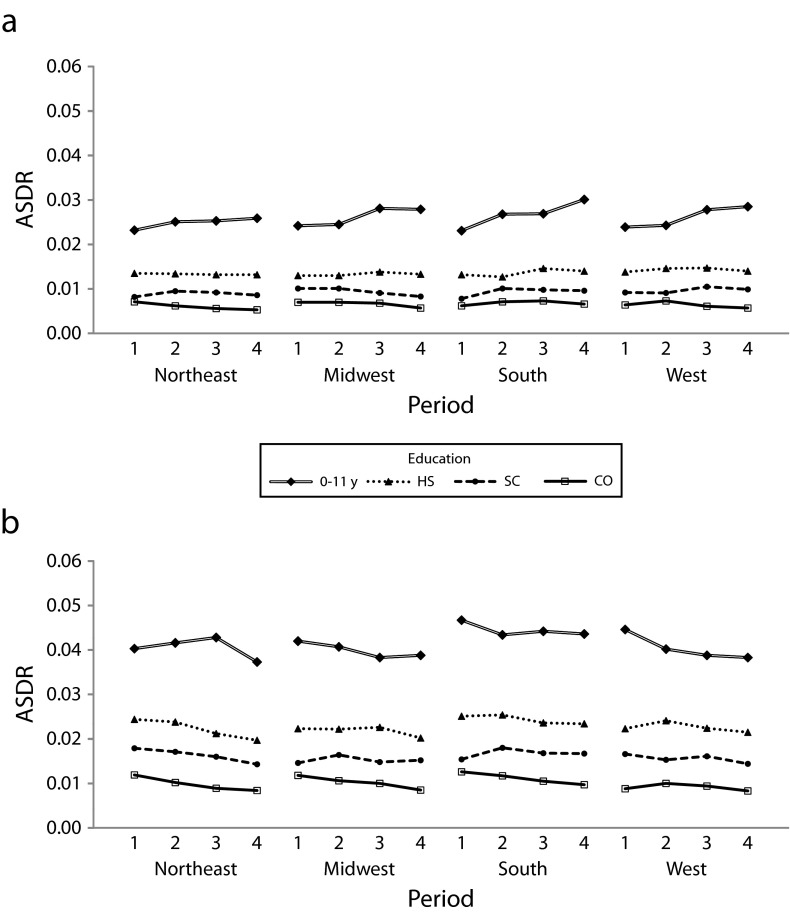

Figure 1 displays the death rates from Table 1. Several findings are noteworthy. Trends in death rates by education level were fairly similar across regions. However, despite the overall similarity, some interesting nuances exist. One nuance was that the mortality increase among women with 0 to 11 years of education in the Northeast was comparatively shallow. The Northeast also had the largest mortality declines among college-educated women. Women’s mortality did not decline for any education level we examined in the South.

FIGURE 1—

Age-standardized death rates (ASDRs) across time period by education level among (a) White women aged 45–84 years and (b) White men aged 45–84 years: 1986–2006 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File.

Note. CO = bachelor’s degree or higher; HS = high-school credential; SC = some college or associate’s degree. Period 1 = 1986–1991; period 2 = 1992–1996; period 3 = 1997–2001; period 4 = 2002–2006.

Among men, Figure 1 reveals few regional differences, although the West was somewhat unusual. College-educated men’s mortality was low in the West in the mid-1980s and changed little. Because their mortality changed little while less-educated men’s mortality declined, the SRD and SRR in the West narrowed to a small degree (the trend was not statistically significant). By 2002–2006 the mortality of college-educated men in the Northeast and Midwest, but not in the South, had declined to levels statistically indistinguishable from the West (confirmed in ancillary tests).

Non-Hispanic Blacks.

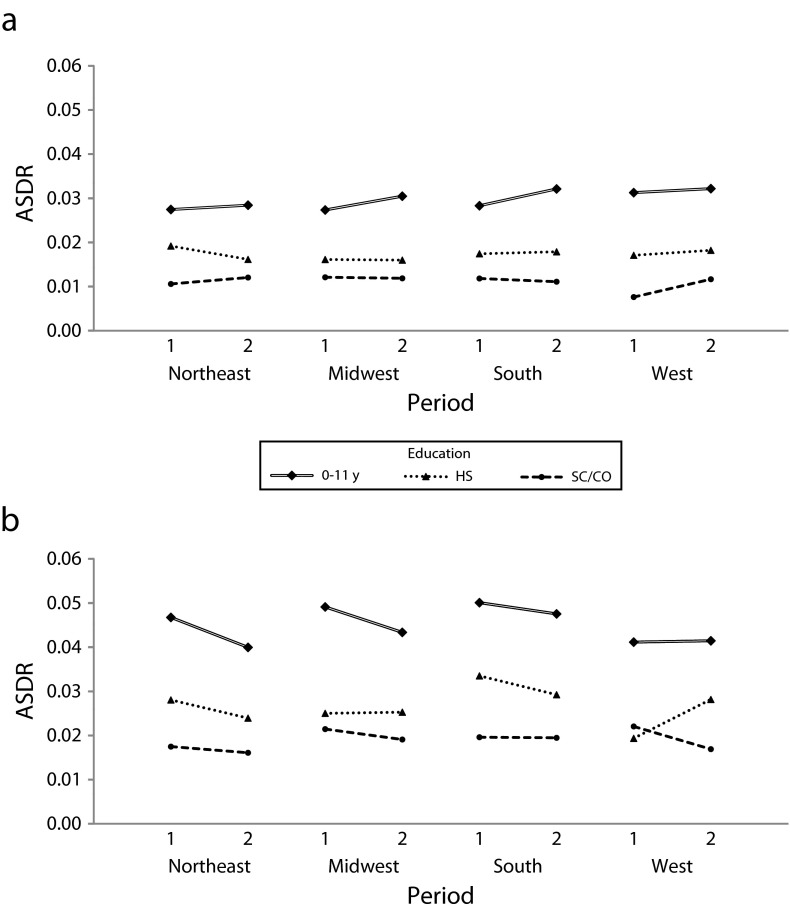

Figure 2 displays the death rates for Blacks (the rates, SRD, and SRR are provided in Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The trends in the West must be interpreted cautiously because of the small number of deaths. Outside the West, the trends mirror those among Whites: trends in the gradient were fairly similar across regions for men, and the mortality increase of low-educated women was comparatively shallow in the Northeast.

FIGURE 2—

Age-standardized death rates (ASDRs) across time period by education level among (a) Black women aged 45–84 years and (b) Black men aged 45–84 years: 1986–2006 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File.

Note. HS = high-school credential; SC/CO = at least some college education. Period 1 = 1986–1996; period 2 = 1997–2006.

Especially Wide or Narrow Gradients Among Regions and Changes Over Time

No region definitively and consistently exhibited the widest or narrowest gradient (measured by the SRD) throughout the study for women or men. However, some regional patterns were apparent.

Among White women, the Northeast often had the narrowest gradient and its distinction grew over time. The Northeast also had the narrowest gradient by the end of the study among Black women. Among men, the South generally had the widest gradient by a small margin.

Extent of Increase in Low-Educated Women’s Mortality Across Regions

Table 2 contains logistic nonstandardized parameter estimates predicting White women’s ln(odds) of death from age, period, education (dichotomized into less than high school vs all others), and an education-by-period interaction term. The significant and positive interaction coefficients indicate that the mortality gap between low-educated and other women widened in all regions. Moreover, the gap widened to a similar extent in each region (95% confidence intervals for the interaction coefficients overlap). Table 2 also contains coefficients predicting the ln(odds) of death across time among low-educated White women. The coefficients for time indicate that the mortality increase was significant within all regions except the Northeast. The mortality increase in the Northeast was about half as large as that in other regions. However, 95% confidence intervals for the period coefficients overlap in all regions.

TABLE 2—

Logistic Unstandardized Parameter Estimates Predicting the ln(Odds) of Death From Age, Period, and Education Among Women Aged 45 to 84 Years: 1986–2006 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File

| Models | United States | Northeast | Midwest | South | West |

| White women | |||||

| Model Aa | |||||

| Intercept, b | −11.152*** | −11.360*** | −11.206*** | −10.900*** | −11.359*** |

| Age, b | 0.091*** | 0.093*** | 0.092*** | 0.087*** | 0.094*** |

| Period,b b | −0.004** | −0.007* | −0.008** | 0.001 | −0.005c |

| LTHS,d b | 0.346*** | 0.307*** | 0.338*** | 0.389*** | 0.315*** |

| LTHS × period, b (SE)e | 0.015*** (0.002) | 0.011* (0.005) | 0.017*** (0.005) | 0.012*** (0.003) | 0.018** (0.006) |

| Deaths, no. | 42 436 | 9401 | 11 334 | 14 200 | 7501 |

| AIC (interaction)f | 31 515 217 | 6 997 655 | 8 227 466 | 10 779 599 | 5 504 274 |

| AIC (main)f | 31 518 459 | 6 998 086 | 8 228 611 | 10 780 381 | 5 504 951 |

| Model Ba | |||||

| Intercept, b | −9.584*** | −9.839*** | −9.450*** | −9.534*** | −9.771*** |

| Age, b | 0.074*** | 0.077*** | 0.073*** | 0.074*** | 0.077*** |

| Period, b (SE) | 0.011*** (0.002) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.010**(0.004) | 0.014*** (0.003) | 0.013* (0.006) |

| Deaths, no. | 14 156 | 3183 | 3787 | 5541 | 1645 |

| Black women | |||||

| Model Aa | |||||

| Intercept, b | −9.493*** | −9.508*** | −9.459*** | −9.374*** | −10.504*** |

| Age, b | 0.071*** | 0.071*** | 0.070*** | 0.070*** | 0.084*** |

| Period,b b | −0.038 | −0.074 | −0.001 | −0.076 | 0.171 |

| LTHS,d b | 0.336*** | 0.259*** | 0.373*** | 0.325*** | 0.414*** |

| LTHS × period, b (SE)e | 0.131* (0.056) | 0.105 (0.105) | 0.081 (0.132) | 0.195* (0.077) | −0.164 (0.240) |

| Deaths, no. | 9265 | 1657 | 1770 | 5092 | 746 |

| AIC (interaction)f | 4 802 330 | 858 189 | 876 010 | 2 746 223 | 320 669 |

| AIC (main)f | 4 802 655 | 858 226 | 876 030 | 2 746 615 | 320 701 |

| Model Ba | |||||

| Intercept, b | −8.628*** | −8.761*** | −8.417*** | −8.616*** | −9.040*** |

| Age, b | 0.063*** | 0.064*** | 0.060*** | 0.063*** | 0.070*** |

| Period, b (SE) | 0.098** (0.035) | 0.037 (0.084) | 0.086 (0.087) | 0.122** (0.045) | 0.020 (0.131) |

| Deaths, no. | 4974 | 776 | 866 | 3018 | 314 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; LTHS = less than high school education.

Model A includes all women regardless of education level. Model B only includes women with 0–11 years of education.

For White women, the 4 periods are 1986–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001, and 2002–2006, assigned x-values of −8.0, −2.5, 2.5, 7.5. For Black women, the 2 periods are 1986–1996 and 1997–2006, assigned x-values of −0.5, 0.5.

P < .1, which is meaningful because the trend test is based on 4 data points.

Less than high school education (i.e., 0–11 years), which is assigned a value of 1. All other education levels are assigned a value of 0.

Standard error of the LTHS × period interaction estimate.

AIC (interaction) refers to the model containing the interaction term. AIC (main) refers to the model without the interaction, not shown.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Among Black women, the widening mortality gap was statistically significant only in the South (Table 2). The increasing mortality among low-educated Black women was statistically significant only in the South; the increase was also sizable in the Midwest but the small number of deaths may have hindered statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

The educational gradient of US adult mortality has increased at the national level since at least the mid-1980s. Studies investigating the reasons have largely focused on national trends in causes of death by education level. Though informative, they have drawn attention to microlevel behavioral explanations and overlooked contextual factors that are the social and economic drivers of behaviors and health. This study began to address this gap by investigating regional trends in the gradient among non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks aged 45 to 84 years during 1986 to 2006.

Four findings are noteworthy. First, trends in the gradient differed little among regions. More research is needed to understand the extent to which this reflects a common core of causes or variation across smaller areas (e.g., states, counties) that is masked at the region level. Second, despite the overall consistency, trends in the gradient among women exhibited a few subtle differences. The gradient among women increased least in the Northeast and most in the South. In the Northeast, low-educated White women did not experience a significant mortality increase (unlike other regions) and college-educated women experienced slightly larger declines in mortality compared with other regions. The differences were subtle and should be interpreted cautiously. For instance, even though the mortality increase among low-educated women in the Northeast was visibly shallow and not statistically significant, it was not significantly different from the mortality increase in other regions. In the South, women’s mortality did not decline for any education level we examined. Third, the gradient shrunk to a small (but statistically insignificant) degree among White men in the West because college-educated men’s mortality was low in the mid-1980s and changed little, and low-educated men’s mortality declined. Fourth, the trends differed more by gender than by race. Within regions, the absolute gradient changed little among men but widened among women.

Our finding that low-educated women in the Northeast did not experience a significant mortality increase is intriguing. The reasons are likely complex. They may partly reflect the region’s economic policies and tobacco-control strategies if one considers that the rising importance of education for economic well-being and smoking were major contributors to women’s widening gradient at the national level,19 and the Northeast has become fairly distinct on these characteristics. Since the early 1980s, the Northeast has implemented economic policies that are particularly beneficial for the poor. The region has emerged as having the most progressive tax policies.37 Relatedly, states that have enacted their own Earned Income Tax Credit tend to cluster in the Northeast and Midwest.37 The Northeast has also emerged as the region with the highest social expenditures per capita.37 Northeastern states also tend to have the most generous Medicaid programs.48,49 In addition, during the 1980s and 1990s, cigarette prices climbed most steeply in the Northeast and West.39

Our finding that increases in the gradient among women were smallest in the Northeast and largest in the South concurs with regional trends in the occupational gradient in ischemic heart disease mortality during the 1970s.50 Our results also suggest that the longevity gains Murray et al.26 found in the Northeast reflect a relatively large mortality decline among college-educated women combined with a relatively shallow mortality increase among low-educated women. Our results also suggest that the longevity declines Murray et al. found in the South reflect stable or rising mortality among women across education levels.

Limitations and Next Steps

Despite the importance of regional analyses, they (like national analyses) may mask heterogeneity across smaller areas. Future studies should investigate trends in the gradient within states and counties to complement our findings. As Murray et al.26 noted, the United States will likely need a core strategy to reduce the inequalities but key interventions may differ across areas. Analyses of small areas may require vital statistics and thus must contend with inaccuracies of education data on death certificates42,51 and higher risks of misclassifying adults to geographic areas.

Another limitation is that country of birth was not available in all NHIS surveys, although ancillary results with the available years were similar. Unfortunately we did not have information about time lived in the region. However, regional migration is rare. For example, between 2011 and 2012, 1.9% of adults aged 25 years or older moved counties and just 0.8% moved regions.52 Moreover, among older adults, migration does not vary by education or women’s health, although it varies somewhat (in a U-shape) by men’s health.53 In sensitivity analyses, we restricted follow-up to 5 years to mitigate regional migration. The analyses generally corroborated our findings, with 1 exception: mortality of low-educated men did not decline in the Northeast in 2002–2006. However, their mortality did not decline nationally in the sensitivity analysis, which casts doubt on a migration explanation. The 2002–2006 period contained few deaths in the shortened follow-up so the estimates have a high margin of error.

Mortality rates from the NHIS-LMF are lower than vital statistics because the survey excludes institutionalized adults. We tested the extent to which this might affect our results by restricting the sample to adults who survived at least 1 year from interview,54 but we found a negligible impact. Also note that compositional changes among the low-educated might partly explain the trends. Previous studies have found limited support for this explanation, although more research is needed.14,54–56 Last, future studies may want to investigate geographic trends in the gradient for income and to decouple period and cohort effects.57

Conclusions

Trends in the educational gradient of mortality among US adults aged 45 to 84 years during 1986 to 2006 exhibited a few subtle regional differences. Women in the Northeast often had the narrowest gradient and the region’s distinction grew over time mainly because low-educated women in the Northeast did not experience a significant mortality increase like their counterparts in other regions (particularly for White women). Among men, trends in the gradient were similar across regions except in the West where the gradient marginally narrowed among White men. The subtle differences indicate that geographic context can accentuate or suppress trends in the gradient. Studies of smaller areas may provide insights into the specific contextual characteristics (e.g., state policies) that have shaped the trends, and thus help explain and reverse the widening mortality disparities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program at Harvard University, the National Institute on Aging (grant 1 R01 AG040248-02; Lisa F. Berkman, PI), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society.

The authors are grateful for the insightful critiques of 3 anonymous reviewers.

Human Participant Protection

This study is exempt from institutional review board approval because data were publicly available and de-identified.

References

- 1.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hummer RA, Lariscy JT. Educational attainment and adult mortality. In: Rogers RG, Crimmins EM, editors. International Handbook of Adult Mortality. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2011. pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Groenhof F et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among women and among men: an international study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(12):1800–1806. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, Social Status, and Health. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitagawa EM, Hauser PM. Differential Mortality in the United States: A Study in Socioeconomic Epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/default.aspx. Accessed August 31, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Crimmins EM, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman JJ, Makuc DM, Kleinman JC, Cornoni-Huntley J. National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(5):919–933. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauderdale DS. Education and survival: birth cohort, period, and age effects. Demography. 2001;38(4):551–561. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and may not catch up. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1803–1813. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(2):103–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preston SH, Elo IT. Are educational differentials in adult mortality increasing in the United States? J Aging Health. 1995;7(4):476–496. doi: 10.1177/089826439500700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogot E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. Life expectancy by employment status, income, and education in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Public Health Rep. 1992;107(4):457–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):350–360. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montez JK, Hummer RA, Hayward MD, Woo H, Rogers RG. Trends in the educational gradient of US adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Res Aging. 2011;33(2):145–171. doi: 10.1177/0164027510392388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Murray T, Thun MJ. Widening of socioeconomic inequalities in US death rates, 1993–2001. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miech R, Pampel F, Kim J, Rogers RG. The enduring association between education and mortality: the role of widening and narrowing disparities. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76(6):913–934. doi: 10.1177/0003122411411276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montez JK, Zajacova A. Trends in mortality risk by education level and cause of death among US White women from 1986 to 2006. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):473–479. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montez JK, Zajacova A. Explaining the widening education gap in mortality among US White women. J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(2):165–181. doi: 10.1177/0022146513481230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson RT, Sorlie P, Backlund E, Johnson N, Kaplan GA. Mortality effects of community socioeconomic status. Epidemiology. 1997;8(1):42–47. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ezzati M, Friedman AB, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJL. The reversal of fortunes: trends in county mortality and cross-county mortality disparities in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):557–568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA. Poverty, time, and place: variation in excess mortality across selected US populations, 1980–1990. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(6):325–334. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.6.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, Lynch JW, Cohen RD, Balfour JL. Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. BMJ. 1996;312(7037):999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(9):1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray CJL, Kulkarni SC, Michaud C et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across race, counties, and race–counties in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steenland K, Henley J, Calle E, Thun M. Individual- and area-level socioeconomic status variables as predictors of mortality in a cohort of 179,383 persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(11):1047–1056. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waitzman NJ, Smith KR. Phantom of the area: poverty-area residence and mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):973–976. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kindig DA, Cheng ER. Even as mortality fell in most US counties, female mortality nonetheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(3):451–458. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137–1143. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):615–623. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ. 1996;312(7037):1004–1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7037.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klinenberg E. Heat Wave. A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Bureau of the Census. Statistical groupings of states and counties. In: Geographic Areas Reference Manual, 1994. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/pdfs/GARM/Ch6GARM.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2013.

- 36.Goldin C. America’s graduation from high school: the evolution and spread of secondary schooling in the twentieth century. J Econ Hist. 1998;58(2):345–374. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman KS, O’Brien RL. Taxing the Poor. Doing Damage to the Truly Disadvantaged. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Florida R. The Rise of the Creative Class. Revisited. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/statesystem. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- 40.Minnesota Population Center. Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. Available at: http://www.ihis.us. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- 41.Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. The National Health Interview Survey (1986–2004) Linked Mortality Files, mortality follow-up through 2006: matching methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rostron BL, Boies JL, Arias E. Education reporting and classification on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2. 2010;(151):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingram DD, Lochner KA, Cox CS. Mortality experience of the 1986–2000 National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality Files participants. Vital Health Stat 2. 2008;(147):1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeAre D. Geographical Mobility: March 1990 to March 1991, US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1992. pp. 20–463. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader M-J, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of U.S. socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–482. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement. Washington DC: US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blakely T, Tobias M, Atkinson J. Inequalities in mortality during and after restructuring of the New Zealand economy: repeated cohort studies. BMJ. 2008;336(7640):371–375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39455.596181.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erdman K, Wolfe SM. Poor Health Care for Poor Americans: A Ranking of State Medicaid Programs. Washington, DC: Public Citizen Health Research Group; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramírez de Arellano AB, Wolfe SM. Unsettling Scores: A Ranking of State Medicaid Programs. Washington, DC: Public Citizen Health Research Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wing S, Casper M, Hayes CG, Dargent-Molina P, Riggan W, Tyroler HA. Changing association between community occupational structure and ischaemic heart disease mortality in the United States. Lancet. 1987;2(8567):1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. Validity of education information on the death certificate. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):437–439. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199607000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.US Bureau of the Census. Geographical mobility: 2011 to 2012. Table 1. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/migration/data/cps/cps2012.html. Accessed April 22, 2013.

- 53.Halliday TJ, Kimmitt MC. Selective migration and health in the USA, 1984–93. Population Stud. 2008;62(3):321–334. doi: 10.1080/00324720802339806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cutler DM, Lange F, Meara E, Richards-Shubik S, Ruhm CJ. Rising educational gradients in mortality: the role of behavioral risk factors. J Health Econ. 2011;30(6):1174–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blau FD. Trends in the well-being of American women, 1970–1995. J Econ Lit. 1998;36(1):112–165. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martikainen P, Blomgren J, Valkonen T. Change in the total and independent effects of education and occupational social class on mortality: analyses of all Finnish men and women in the period 1971–2000. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(6):499–505. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.049940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masters RK, Hummer RA, Powers DA. Educational differences in US adult mortality: a cohort perspective. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):548–572. doi: 10.1177/0003122412451019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]