Abstract

Objective

To determine the genetic cause of congenital ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, facial paralysis and mild hypotonia segregating in two pedigrees diagnosed with atypical Moebius syndrome or congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles (CFEOM).

Methods

Homozygosity mapping and whole-exome sequencing were conducted to identify causative mutations in affected family members. Histories, physical examinations, and clinical data were reviewed.

Results

Missense mutations resulting in two homozygous RYR1 amino acid substitutions (E989G and R3772W) and two compound heterozygous RYR1 substitutions (H283R and R3772W) were identified in a consanguineous and a non-consanguineous pedigree, respectively. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed marked hypoplasia of extraocular muscles and intraorbital cranial nerves. Skeletal muscle biopsies revealed non-specific myopathic changes. Clinically, the patients’ ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness were far more significant than their hypotonia and limb weakness, and were accompanied by an unrecognized susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia.

Conclusions

Affected children presenting with severe congenital ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness in the setting of only mild skeletal myopathy harbored recessive mutations in RYR1, encoding the ryanodine receptor 1, and were susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. While ophthalmoplegia occurs rarely in RYR1-related myopathies, these children were atypical because they lacked significant weakness, respiratory insufficiency, or scoliosis.

Clinical relevance

RYR1-associated myopathies should be included in the differential diagnosis of congenital ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness, even without clinical skeletal myopathy. These patients should also be considered susceptible to malignant hyperthermia, a life-threatening anesthetic complication avoidable if anticipated pre-surgically.

Introduction

The RYR1 gene (OMIM 180901) on chromosome 19q13.1 encodes the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor RYR1, the principal sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca+2 release channel that plays a pivotal role in excitation-contraction coupling in muscle. Both recessive and dominant mutations in RYR1 are increasingly recognized to cause a spectrum of congenital myopathies, including central core,1–4 multi-minicore,5, 6 nemaline7 and congenital fiber-type disproportion myopathy.8 Congenital ophthalmoplegia can segregate with RYR1 mutations and, in particular, with multi-minicore myopathy.9, 10 Children with RYR1 mutations and ophthalmoplegia typically have severe skeletal myopathy accompanied by respiratory insufficiency, and develop scoliosis.6,11 Some RYR1 mutations cause susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia,12–15 and ophthalmoplegia and malignant hyperthermia can also be co-inherited.16,17

We previously reported three children within a consanguineous pedigree with congenital bilateral complete ophthalmoplegia, facial diplegia, and only mild hypotonia, who had been diagnosed with atypical Moebius syndrome.18 Subsequently, we identified a non-consanguineous pedigree in which two children have a similar phenotype and had been diagnosed with congenital fibrosis of extra-ocular muscles (CFEOM). Utilizing next-generation exome sequencing (NGS), we identify recessive RYR1 mutations in affected members of both families, and also discover that these individuals are susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. These findings highlight the importance of recognizing RYR1-related myopathies in the differential diagnosis of congenital ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by Boston Children’s Hospital and University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Boards. Written informed consent was obtained from participating family members or from their guardians. All investigations were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Pedigree OH is a consanguineous pedigree of Mexican ethnicity (Figure 1A), and we previously reported the medical histories and ophthalmic examinations of the affected subjects, III:3, III:4 and IV:1.18 Pedigree DR is a previously unreported non-consanguineous pedigree of Portuguese origin with two affected children who are dizygotic twins (Figure 1B).

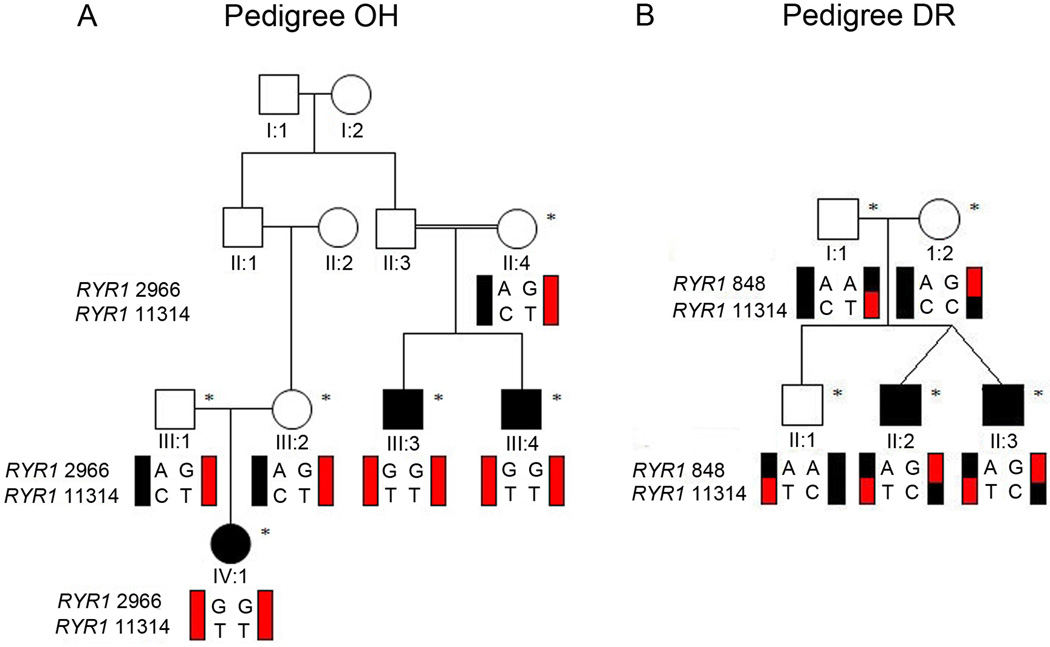

Figure 1. Pedigree structures of OH and DR.

Schematic of pedigrees OH (A) and DR (B). Genotypes of RYR1 variants c.2966A>G and c.11314C>T in pedigree OH, and of variants c.848A>G and c.11314C>T in pedigree DR are shown under genotyped family members; black schematic haplotype bars denote wildtype sequence, while red schematic haplotype bars denote mutant sequence. Note that the clinically unaffected parents in pedigree OH each harbor the same two RYR1 mutations on one allele (red), and have one wild-type allele (black). The clinically unaffected parents in pedigree DR each harbor a single, different RYR1 mutation on one allele (half red and half black) and have one wild-type allele (black). DR I:1 harbors the identical c.11314C>T mutation also harbored as one of the two mutations carried by OH II:4, III:1, and III:2. Squares, males; circles, females; filled symbol, affected; asterisk, enrolled in the study.

Mutation identification in pedigree OH

Homozygosity mapping

To identify the genetic etiology for the clinical phenotype in pedigree OH, DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of three affected family members (III:3, III:4 and IV:1) and three unaffected parents (II:4, III:1 and III:2) using the Puregene kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genotyping was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip Mapping 10k Xba array (Affymetrix Inc.)19 based on previously published protocols.20 Given consanguinity in the family, we assumed a recessive mode of inheritance and predicted the causative variant would fall in a region of shared homozygosity. Homozygosity mapping was performed using dChip software.21, 22

Exome Capture and Sequencing, Read Mapping and Variant Annotation

We performed whole-exome sequencing on DNA from individuals III:3, III:4 and IV:1. Three μg of genomic DNA was processed with the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit v.1 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).23 Captured libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiScanSQ (Illumina, San Diego, CA).24 After sequencing, high-quality reads were aligned to the human reference genome sequence (UCSC hg18, NCBI build 36.1) via the ELAND v2 program (Illumina). Variant calling of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels) was done with CASAVA software (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Data analysis and mutation identification

ANNOVAR annotation Package25 was used for variant annotation. Polymorphisms were excluded by filtering high-quality variants against dbSNP13026 and 1000 Genomes Project data27 as well as by excluding variants with >1% frequency in Exome Variant Server (EVS), NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Seattle, WA. Only novel coding splice site, missense, nonsense variants and indels were retained for final variant analysis. Prediction of functional consequences of non-synonymous mutations was done using SIFT,28 PolyPhen-229 and Pmut30 algorithms. Putative mutations were then confirmed and segregation with affection status was tested among family members using Sanger sequencing.

Mutation identification in pedigree DR

Whole exome sequencing was performed on a DNA sample from the affected individual DR II:2. Three μg of genomic DNA was processed with the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit v.4 plus UTRs. Captured libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000. High-quality reads were aligned to the human reference genome sequence (UCSC hg19, NCBI build 37.1) via BWA program.31 Variant calling of SNPs and indels was done using Samtools.32 Resulting data was analyzed assuming recessive inheritance where both homozygous and compound heterozygous variants were investigated. The methodologies described above for mutation identification and to confirm segregation were followed.

Clinical, radiological, and pathological assessment

Following analysis of the genetic results, 11-year old subject OH IV:1 underwent confirmatory clinical diagnostic DNA testing and a battery of clinical procedures including muscle biopsy, electromyography, nerve conduction velocity, electrocardiography, pulmonary function tests and blood and CSF analyses. Available medical histories of the other two affected subjects in pedigree OH were reviewed.

Full ophthalmic and neurological examinations were conducted when DR II:2 and DR II:3 were 8 months old. Individual DR II:2 had had cytogenetic analysis, and underwent real-time sonographic imaging and non-enhanced computerized tomography of the brain, as well as MR imaging of the brain and orbits as previously described.18 Their available subsequent medical histories were reviewed.

Muscle specimens from individuals OH IV:1 and DR II:2 were obtained for clinical diagnostic studies from the quadriceps muscle under local anesthesia. Specimens were frozen immediately in isopentane-cooled liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Sections of fresh-frozen muscle were stained for hematoxylin and eosin, modified trichrome, myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) at pH 4.3, 4.6, and 9.4, periodic acid-Schiff (without and with diastase), Oil Red O, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase-tetrazolium reductase, succinic dehydrogenase, cytochrome oxidase, alkaline phosphatase, and acid phosphatase. Samples for electron microscopy were fixed in 5% glutaraldehyde and 1% osmium tetraoxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer.

RESULTS

Genetic analysis

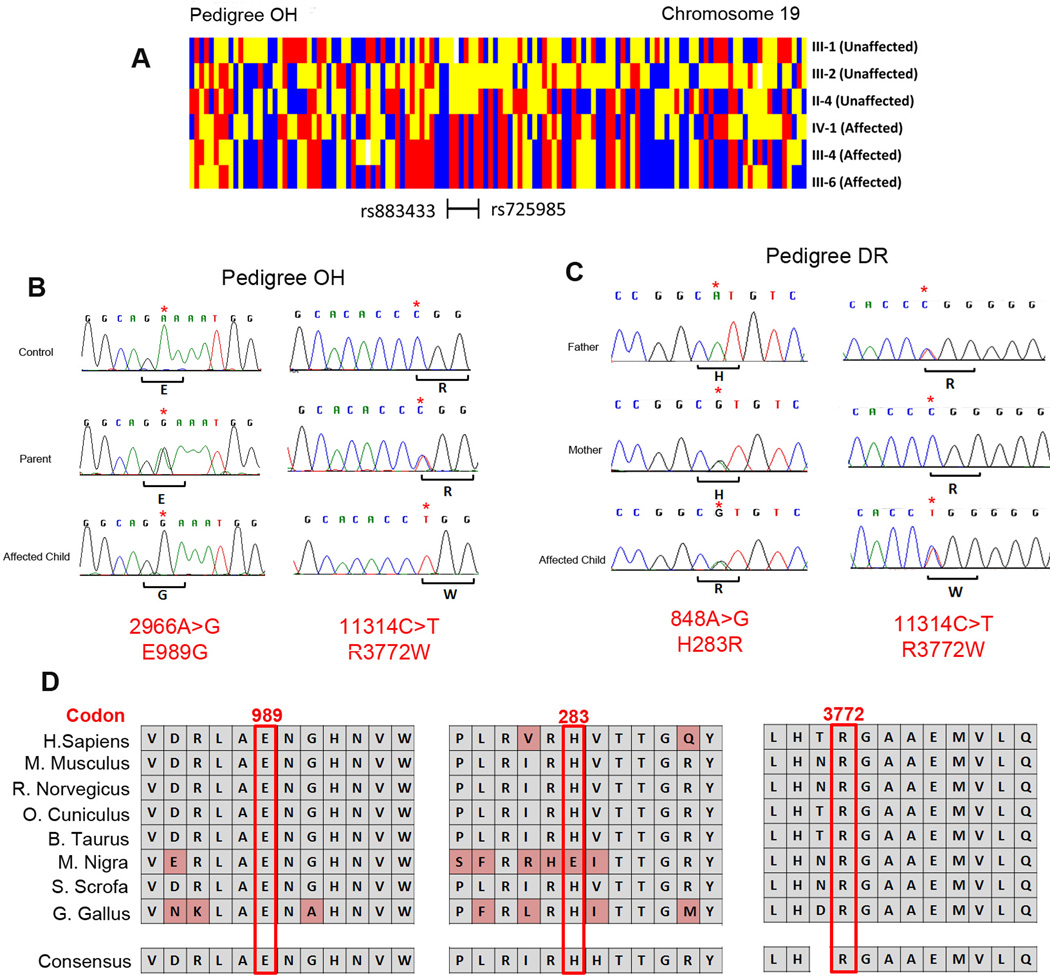

Homozygosity mapping in pedigree OH revealed only one homozygous region greater than 2Mb that was shared among the three affected individuals and not the unaffected parents. This ~3Mb region on chromosome 19q13.12-19q13.2 was flanked by markers rs725985 and rs883433 (Figure 2A). Because there were more than 150 genes in the region, we proceeded to whole-exome sequencing (WES) for causative variant identification. We obtained mean coverage of 88% at 10X resulting in ~18000 exonic variants in each sample. Since we hypothesized a recessive mode of inheritance, we investigated the homozygous novel variants falling within the shared region of homozygosity (19q13.12-19q13.2) that were not in dbSNP, 1000 genomes or EVS databases. This analysis resulted in only 2 homozygous missense variants, both of which fell within the RYR1 gene (OMIM: 180901, ryanodine receptor 1 (skeletal)): c.2966A>G; p.E989G and c.11314C>T; p.R3772W (Table 1). Both residues are highly conserved (Figure 2D) and in silico analysis predicted both to be damaging. Both variants were absent from control DNA samples and segregated with affection status; unaffected parents were heterozygous and the affected individuals were homozygous for the mutant alleles (Figure 2B). Neither of the mutations fell in any of the dominant ‘hotspot’ regions of RYR1 mutations, consistent with previously reported recessive RYR1 mutations which appear to alter residues anywhere along the length of RYR1 protein.33

Figure 2. Homozygosity mapping and mutation analysis.

(A) Schematic showing regions of shared homozygosity on chromosome 19 in pedigree OH created by genotypes from individuals III:1, III:2, II:4, IV:1, III: 4 and III:6 by dChip software.22 Red or blue denotes homozygous AA or BB; yellow denotes heterozygous AB, and white denotes absent call. The homozygous region shared by the 3 affected children and no parent is bordered by single nucleotide markers rs725985 and rs886466. (B) Sanger sequencing chromatograms from an unrelated control individual (top), and from an unaffected parent (middle) and affected child (bottom) of pedigree OH. Note that the parent is heterozygous and the affected children are homozygous for RYR1 c.2966A>G (left) and RYR1 c.11314C>T (right) nucleotide substitutions. The wild-type and the predicted amino acid substitutions are provided below each sequence. (C) Sanger sequencing chromatograms from unaffected father (top), unaffected mother (middle) and an affected child (bottom) of pedigree DR. The father has wild-type sequence at RYR1 c.848 and a heterozygous RYR1 11314C>T nucleotide substitution, the mother has a heterozygous RYR1 848A>G nucleotide substitution and is wild-type at RYR1 c.11314. The affected child is heterozygous at both nucleotides. The wild-type and the predicted amino acid substitutions provided below each sequence. (D) Evolutionary conservation of RYR1 glutamic acid 989, histidine 283 and arginine 3772 residues in 8 species.

Table 1.

Exome sequence data (Pedigree OH)

| OH III:3 | OH III:4 | OH IV:1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Coverage at 10X | 91 | 84 | 89.9 |

| Total SNPs | 18494 | 17115 | 18662 |

| Novel SNPs | 1302 | 1098 | 632 |

| (+) pathogenic | 921 | 725 | 471 |

| (+) homozygous | 60 | 120 | 42 |

| (+) chromosome 19q13.12-19q13.2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| (+) shared by other 2 affected | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Upon identification of RYR1 mutations in pedigree OH, we reviewed the cohort of families referred to us with ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness, and identified a second pedigree, DR, with a phenotype similar to pedigree OH. We hypothesized that RYR1 mutations could also be causative in this pedigree and, because RYR1 gene is a very large gene encoded by 106 exons, we performed whole-exome sequencing on affected individual DR II:2 and targeted our sequence analysis to the RYR1 gene. We obtained an average coverage of >95% at 10X resulting in 23236 exonic variants. Data was analyzed as described for pedigree OH except, due to absence of consanguinity, we assumed a compound heterozygous model of inheritance. We identified two heterozygous RYR1 missense mutations, a novel c. 848A>G; p.H283R that falls in the first RYR1 hotspot mutation region, and the recurrent mutation c.11314C>T; p.R3772W (Figure 2B). Neither variant existed in any of the common databases or were present in control individuals, both were predicted to be damaging, both altered highly conserved residues, and segregation analysis confirmed that one mutation was inherited from each parent. The unaffected sibling DR II:1 carried the heterozygous missense c. 11314C>T mutation (Figure 2C).

Clinical Assessments

Pedigree OH

As previously reported,18 the three affected members of pedigree OH had normal gestational and birth histories, were born full term. Each had congenital complete ophthalmoplegia. At near central gaze, OH III:3 had exotropia of 18∆, OH III:4 had exotropia of 18∆ and 10∆ hypertopia, and OH IV:1 showed alignment between orthotropia to 10∆ exotropia. All 3 children had in addition bilateral ptosis, and bilateral facial diplegia, while hypotonia was reported for III:3 and IV:1. MR imaging of the affected children had revealed apically-narrowed bony orbits, marked extraocular muscle hypoplasia, abnormally small motor nerves within the orbit, yet normal-appearing brainstems and subarachnoid portions of the cranial nerves innervating the extraocular muscles.18 The children were diagnosed with atypical Moebius syndrome.

The proband, IV:1, underwent additional clinical evaluations at age 11. Intellectual and social development was normal. She had nonprogressive complete ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, and facial weakness. She had mild hypotonia, deep tendon reflexes were +1, and she had normal axial and limb muscle strength apart from weak ankle dorsiflexion. She had ankle contractures and toe-walked; otherwise her gait was normal. Sensory examination and coordination were normal and she had no history of respiratory compromise or scoliosis. Nerve conduction velocity and repetitive nerve stimulation were normal, while electromyography revealed decreased motor unit duration and early recruitment in the anterior tibialis consistent with a myopathic process. Electrocardiography and echocardiography were normal while pulmonary function tests showed a low maximum expiratory pressure. Creatine kinase levels were normal. Tests for metabolic and mitochondrial diseases including genetic screening were found to be normal except for low free and total carnitine levels. IV:1 is receiving carnitine and vitamin supplements, and physiotherapy for her ankle contractures.

Review of the intervening medical histories of her two affected cousins revealed nonprogressive ophthalmoplegia, ptosis and facial weakness, mild hypotonia and 1+ deep tendon reflexes, with normal sensory testing. Subject III:3 has a history of delayed motor milestones. III:4 had undergone an emergency surgery for a ruptured appendix, complicated by malignant hyperthermia requiring hospitalization with intensive care for 2 weeks.

Pedigree DR

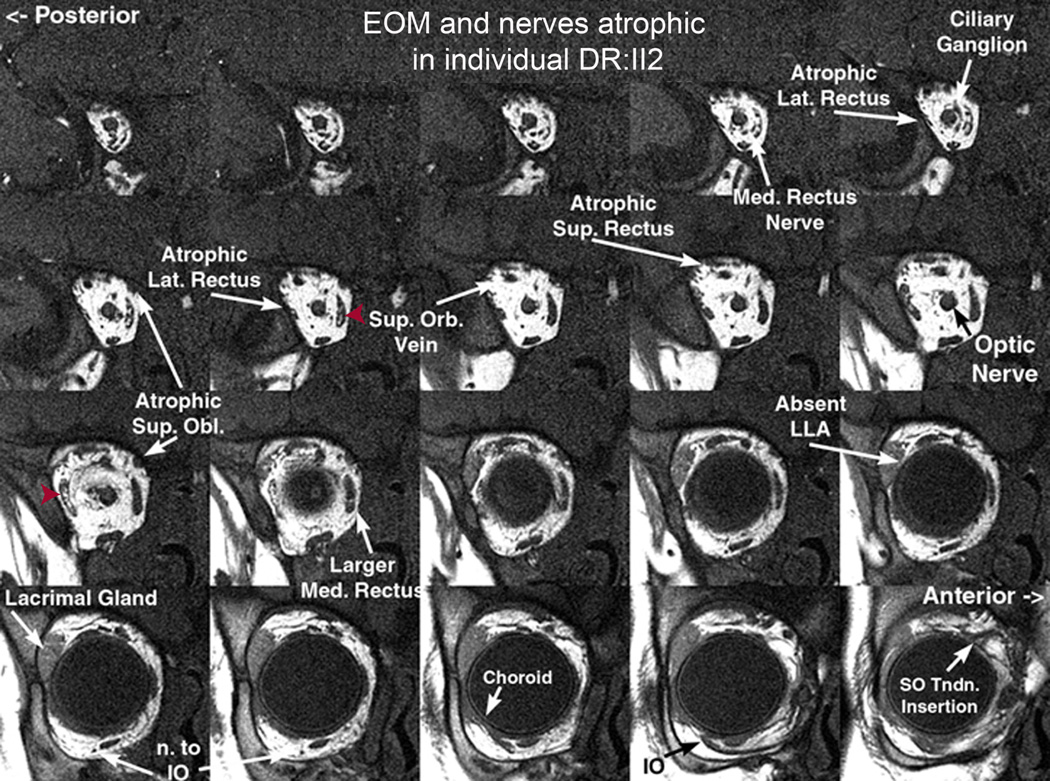

The dizygotic twins were born full term following a pregnancy remarkable only for in-vitro fertilization. The first twin was born vaginally and the second required caesarean section. Both infants had severe neonatal hypotonia and axial weakness. When examined at 8 months of age, tone and muscle strength had improved significantly since birth, but they remained hypotonic; both boys could sit without support for 30 seconds and could pull to stand. They had complete ophthalmoplegia with 16∆ exotropia in central gaze at near, bilateral ptosis, and facial weakness. Deep tendon reflexes were 2+ and symmetric, with no pathological reflexes. At age 12, intellectual and social development was normal. Ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness were unchanged, and both boys had been diagnosed with CFEOM and undergone ptosis surgery. Inability to fully close their eyes has led to drying and corneal perforation in one twin, requiring corneal transplantation. Both boys had difficulties with chewing and swallowing. Both boys had absent patellar reflexes, yet muscle tone was only mildly decreased in one and normal in the other. Neither boy has had respiratory compromise or scoliosis. Laboratory and genetic investigations revealed no metabolic or mitochondrial abnormalities. High-resolution MR imaging of the orbit performed for DR II:2 at 8 months of age revealed atrophy of extraocular muscles with intramuscular fat; the inferior rectus muscles were partially spared. The posterior halves of the superior oblique muscles were more affected than their anterior halves. The intra-orbital nerves to the extraocular muscles were thin and appeared hypoplastic while the optic nerve appeared normal (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Quasi-coronal MRI of the right orbit of individual DRII:2.

Note severe hypoplasia of the lateral and medial rectus muscles, moderate hypoplasia of the superior and inferior obliques, and apparent sparing of the inferior rectus. There is central high-intensity material seen within muscles suggestive of fat deposition (red arrowheads). Nerves to the extraocular muscles appear hypoplastic, while the optic nerve, superior orbital vein and intracoronal fat appear normal. Med, medial; Lat, lateral; Sup, Superior; Orb, orbital; Obl, oblique; LLA, lateral levator aponeurosis; n., nerve; IO, inferior oblique; SO, superior oblique; Tndn, tendon.

Histochemistry and electron microscopy findings

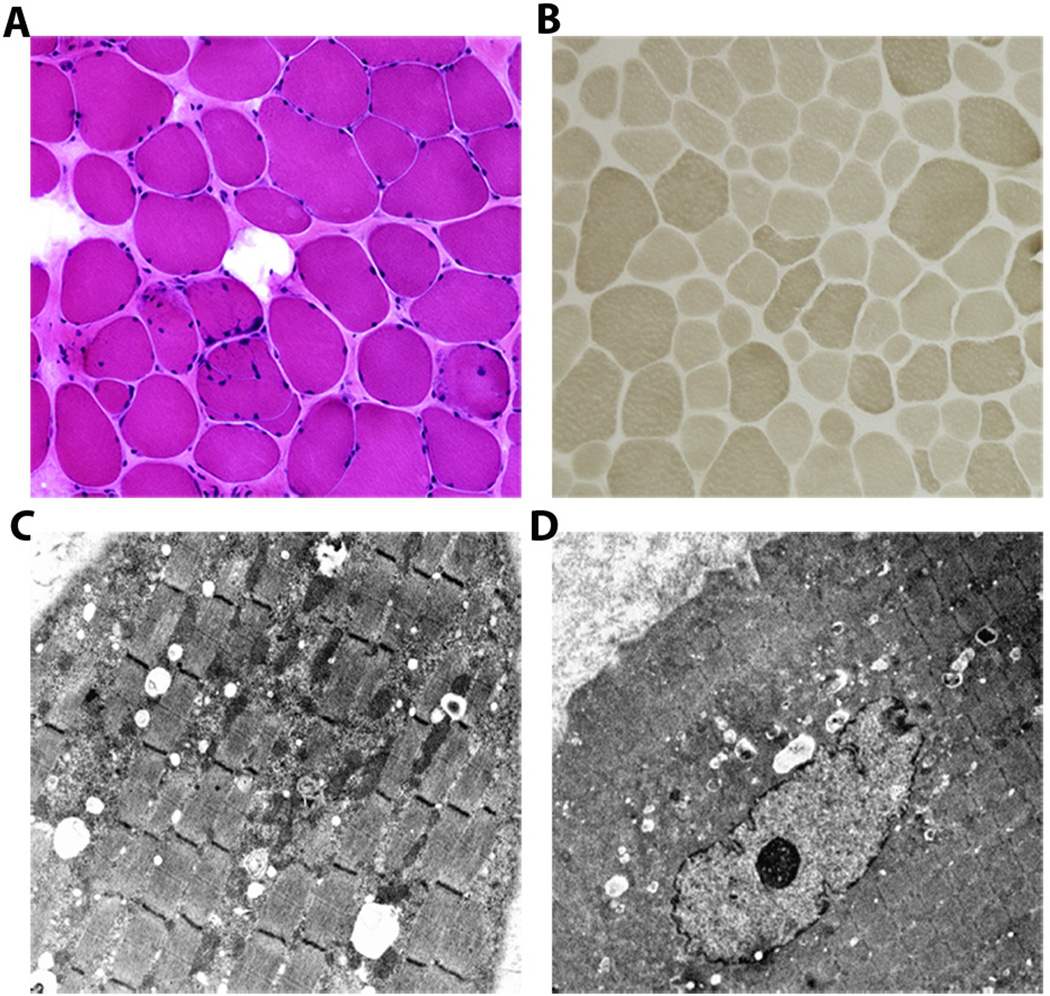

Histochemistry and electron microscopy of the muscle biopsies from individuals OH IV:1 and DR II:2 revealed non-specific myopathic changes (Figure 4). Histochemical analysis revealed variability in fiber size, increased endomysial connective tissue, and some internalized nuclei. Type I and type II fibers were observed with predominance of type I fibers. Multiminicores, central cores, and nemaline rods were not observed. Electron microscopy examination showed similar variation in fiber size with fatty infiltration. Some fibers contained degenerative material with focal accumulation of mitochondria with glycogen and lipid deposition. Focal areas of Z-disc streaming were observed.

Figure 4. Morphological findings of quadriceps muscle biopsy sections from affected individual OH IV:1.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing variability of fiber sizes with increased endomysial connective tissue and some internalized nuclei (20X). (B) Myosin adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) 9.4 stain demonstrating fibers of variable sizes with small type I (light) and II (dark) fibers (10X). Electron micrographs show focal accumulation of mitochondria accompanied by glycogen and lipid droplets (C; 4000X); with some fibers showing an internalized nucleus (D; 2500X).

DISCUSSION

We have studied the affected members of two pedigrees diagnosed with atypical Moebius syndrome or CFEOM and found them to harbor homozygous or compound heterozygous missense mutations in RYR1, leading to their re-diagnosis with RYR1-related myopathy with total ophthalmoplegia and susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia. These families highlight RYR1-related myopathies in the differential diagnosis of congenital ophthalmoplegia and facial weakness, and remind us that risk of malignant hyperthermia can segregate with congenital ophthalmoplegia. They also contribute to the broadening phenotypes associated with RYR1 mutations. Unlike what is typically found in patients with extraocular muscle involvement and RYR1 mutations,5,6, 34,5, 11, 17, 34 these patients had relatively mild hypotonia, quite good muscle strength, and no scoliosis or history of respiratory impairment.

We identified the disease-causing mutations in these patients using NGS, which appears to be a promising diagnostic tool particularly for this disorder. With 106 exons, RYR1 is expensive and time-consuming to Sanger sequence for clinical diagnostics. In addition, RYR1 mutations cause more than 70% of cases of malignant hyperthermia, which is often inherited as a dominant trait.35 To make a clinical diagnosis of susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia a patient must undergo a muscle biopsy for in vitro contraction test, which can yield false negative results. Thus, exome sequencing can be an important and efficient approach to identify recurrent or novel RYR1 mutations.

The three affected children in pedigree OH harbor two different homozygous RYR1 missense mutations. The first is a novel c.2966 A>G substitution replacing a glutamic acid with a glycine at the highly conserved residue 989. The negative charge of the wild-type residue is lost as a result of this mutation and this, together with the smaller size of the mutated residue, could disturb the function of RYR1 or alter its interaction with other molecules.36 The second homozygous mutation is a c.11314C>T substitution replacing an arginine for a tryptophan at residue 3772, which pedigree DR also harbors in the heterozygous state. R3772 is buried within the core of the protein. The pathologic neural tryptophan residue is larger than the negatively charged wild-type arginine residue, and thus may disrupt protein-protein interactions within the core structure.

In addition to the heterozygous R3772W substitution, the affected dizygotic twins in pedigree DR also harbor a novel heterozygous c.848A>G substitution that replaces a histidine for an arginine at residue 283. The wild-type residue is predicted to form hydrogen bonds with threonine and arginine at positions 286 and 256, respectively, and these bonds are predicted to be disrupted when a neutral histidine is replaced with the larger and positively charged arginine.36

The heterozygous R3772W substitution was previously reported to cause dominantly-inherited malignant hyperthermia.37 In our families, it occurs as a recessive mutation in the homozygous or compound heterozygous state, and contributes to a broader phenotype that extends beyond susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia. It is interesting that a similar observation was noted for the R3772Q substitution at the same residue: the heterozygous R3772Q substitution was reported to cause malignant hyperthermia,38 while the homozygous or compound heterozygous R3772Q substitution was found to cause a more severe phenotype including ptosis, facial weakness, non-specific myopathy, and/or malignant hyperthermia.37, 39, 40

The affected children in pedigree OH harbor two homozygous mutations which are both present in their parents in the heterozygous state; thus, both variant are present on the founder allele shared by the three parents. Double-variant mutations in RYR1 have been reported previously in recessively and dominantly inherited phenotypes,17, 37, 39–42 yet their significance remains controversial. In a study of malignant hyperthermia due to RYR1-mutations, there was no overt difference in the clinical presentation or muscle response to halothane or caffeine comparing patients with double mutations on the same allele to those with single mutations, except for a significantly higher level of creatinine kinase in the former group.28 On the other hand, as in our report, it appears that when malignant hyperthermia-causing RYR1 mutations are associated with a second RYR1 mutation, the resulting phenotype can be more extensive.37, 40, 43 Given these observations, the combination of the homozygous R3772W substitution with the novel homozygous E989G substitution in pedigree OH, or the combination of the heterozygous R3772W substitution with the heterozygous H283R substitution in pedigree DR, could explain the more extensive phenotypes seen in our patients. Moreover, the parents and other family members who harbor heterozygous mutations may, themselves, be at risk of malignant hyperthermia.

It is important for ophthalmologists to consider RYR1-myopathies in the differential diagnosis of total ophthalmoplegia. Recognizing the clinical associations presented in this report would protect patients and their asymptomatic relatives from the potential risk of malignant hyperthermia.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this study. We are grateful to the Broad Institute (funds from the National Human Genome Research Institute grant #U54 HG003067, Eric Lander, PI) and the Ocular Genomics Institute at Mass Eye and Ear Institute / Harvard Medical School for generating high-quality sequence data. We also thank Xiaowu Gai for his help with whole-exome data analysis. This study was supported by the Al-Habtoor Dubai-Harvard Foundation fellowship to SS, the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research to ECE, and National Institutes of Health R01EY12498 and R01EY08313. E.C.E. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Role of the Sponsors:

The funding organizations have played no role in the study design, conduct, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Web resources:

dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/

Exome Variant Server (EVS) Database, http://snp.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

1000 Genomes, http://www.1000genomes.org/

The nomenclature was based on the reference sequence RYR1 (RefSeq accession number NM_ 000540)

Contributor Information

Sherin Shaaban, Email: sherin.shaaban@childrens.harvard.edu.

Leigh Ramos-Platt, Email: lramosplatt@chla.usc.edu.

Floyd H. Gilles, Email: fgilles@chla.usc.edu.

Wai-Man Chan, Email: wchan@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

Caroline Andrews, Email: candrews@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

Umberto De Girolami, Email: udegirolami@partners.org.

Joseph Demer, Email: jld@ucla.edu.

Elizabeth C Engle, Email: elizabeth.engle@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Lynch PJ, Tong J, Lehane M, et al. A mutation in the transmembrane/luminal domain of the ryanodine receptor is associated with abnormal Ca2+ release channel function and severe central core disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Mar 30;96(7):4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monnier N, Romero NB, Lerale J, et al. An autosomal dominant congenital myopathy with cores and rods is associated with a neomutation in the RYR1 gene encoding the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000 Nov 1;9(18):2599–2608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monnier N, Romero NB, Lerale J, et al. Familial and sporadic forms of central core disease are associated with mutations in the C-terminal domain of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Human Molecular Genetics. 2001 Oct 15;10(22):2581–2592. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis MR, Haan E, Jungbluth H, et al. Principal mutation hotspot for central core disease and related myopathies in the C-terminal transmembrane region of the RYR1 gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2003 Feb;13(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monnier N, Ferreiro A, Marty I, Labarre-Vila A, Mezin P, Lunardi J. A homozygous splicing mutation causing a depletion of skeletal muscle RYR1 is associated with multi-minicore disease congenital myopathy with ophthalmoplegia. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 May 15;12(10):1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jungbluth H, Zhou H, Hartley L, et al. Minicore myopathy with ophthalmoplegia caused by mutations in the ryanodine receptor type 1 gene. Neurology. 2005 Dec 27;65(12):1930–1935. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188870.37076.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo E, Nishimura T, Kosho T, et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations in a patient with severe congenital nemaline myopathy with ophthalomoplegia identified through massively parallel sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2012 Apr;158A(4):772–778. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke NF, Waddell LB, Cooper ST, et al. Recessive mutations in RYR1 are a common cause of congenital fiber type disproportion. Hum Mutat. 2010 Jul;317:E1544–E1550. doi: 10.1002/humu.21278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungbluth H, Sewry C, Brown SC, et al. Minicore myopathy in children: a clinical and histopathological study of 19 cases. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000 Jun;10(4–5):264–273. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(99)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreiro A, Estournet B, Chateau D, et al. Multi-minicore disease--searching for boundaries: phenotype analysis of 38 cases. Ann Neurol. 2000 Nov;48(5):745–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beggs AH, Agrawal PB. Multiminicore Disease. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLennan DH, Duff C, Zorzato F, et al. Ryanodine receptor gene is a candidate for predisposition to malignant hyperthermia. Nature. 1990 Feb 8;343(6258):559–561. doi: 10.1038/343559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benkusky NA, Farrell EF, Valdivia HH. Ryanodine receptor channelopathies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 Oct 1;322(4):1280–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monnier N, Procaccio V, Stieglitz P, Lunardi J. Malignant-hyperthermia susceptibility is associated with a mutation of the alpha 1-subunit of the human dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type voltage-dependent calcium-channel receptor in skeletal muscle. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Jun;60(6):1316–1325. doi: 10.1086/515454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson RL, Monnier N, Wolz W, et al. A genome wide search for susceptibility loci in three European malignant hyperthermia pedigrees. Hum Mol Genet. 1997 Jun;6(6):953–961. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strazis KP, Fox AW. Malignant hyperthermia: a review of published cases. Anesth Analg. 1993 Aug;77(2):297–304. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199308000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein A, Lillis S, Munteanu I, et al. Clinical and genetic findings in a large cohort of patients with ryanodine receptor 1 gene-associated myopathies. Hum Mutat. 2012 Jun;33(6):981–988. doi: 10.1002/humu.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumars S, Andrews C, Chan WM, Engle EC, Demer JL. Magnetic resonance imaging of the endophenotype of a novel familial Mobius-like syndrome. Journal of AAPOS. 2008 Aug;12(4):381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy GC, Matsuzaki H, Dong S, et al. Large-scale genotyping of complex DNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2003 Oct;21(10):1233–1237. doi: 10.1038/nbt869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuzaki H, Loi H, Dong S, et al. Parallel genotyping of over 10,000 SNPs using a one-primer assay on a high-density oligonucleotide array. Genome Res. 2004 Mar;14(3):414–425. doi: 10.1101/gr.2014904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudbjartsson DF, Thorvaldsson T, Kong A, Gunnarsson G, Ingolfsdottir A. Allegro version 2. Nat Genet. 2005 Oct;37(10):1015–1016. doi: 10.1038/ng1005-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004 May 22;20(8):1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gnirke A, Melnikov A, Maguire J, et al. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2009 Feb;27(2):182–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008 Nov 6;456(7218):53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. Sep;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001 Jan 1;29(1):308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. Oct 28;467(7319):1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. Apr;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrer-Costa C, Gelpi JL, Zamakola L, Parraga I, de la Cruz X, Orozco M. PMUT: a web-based tool for the annotation of pathological mutations on proteins. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jul 15;21(14):3176–3178. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009 Jul 15;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009 Aug 15;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zorzato F, Jungbluth H, Zhou H, Muntoni F, Treves S. Functional effects of mutations identified in patients with multiminicore disease. IUBMB Life. 2007 Jan;59(1):14–20. doi: 10.1080/15216540601187803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bevilacqua JA, Monnier N, Bitoun M, et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations cause unusual congenital myopathy with prominent nuclear internalization and large areas of myofibrillar disorganization. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011 Apr;37(3):271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg HSN, Riazi S, Dirksen R. GeneReviews™ [Internet] Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2003. Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptibility. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venselaar H, Te Beek TA, Kuipers RK, Hekkelman ML, Vriend G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levano S, Vukcevic M, Singer M, et al. Increasing the number of diagnostic mutations in malignant hyperthermia. Hum Mutat. 2009 Apr;30(4):590–598. doi: 10.1002/humu.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter D, Ismail A, Robinson RL, et al. A RYR1 mutation associated with recessive congenital myopathy and dominant malignant hyperthermia in Asian families. Muscle Nerve. 2009 Oct;40(4):633–639. doi: 10.1002/mus.21397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraeva N, Riazi S, Loke J, et al. Ryanodine receptor type 1 gene mutations found in the Canadian malignant hyperthermia population. Can J Anaesth. 2011 Jun;58(6):504–513. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guis S, Figarella-Branger D, Monnier N, et al. Multiminicore disease in a family susceptible to malignant hyperthermia: histology, in vitro contracture tests, and genetic characterization. Arch Neurol. 2004 Jan;61(1):106–113. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monnier N, Krivosic-Horber R, Payen JF, et al. Presence of two different genetic traits in malignant hyperthermia families: implication for genetic analysis, diagnosis, and incidence of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Anesthesiology. 2002 Nov;97(5):1067–1074. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero NB, Monnier N, Viollet L, et al. Dominant and recessive central core disease associated with RYR1 mutations and fetal akinesia. Brain. 2003 Nov;126(Pt 11):2341–2349. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeong SK, Kim DC, Cho YG, Sunwoo IN, Kim DS. A double mutation of the ryanodine receptor type 1 gene in a malignant hyperthermia family with multiminicore myopathy. J Clin Neurol. 2008 Sep;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2008.4.3.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]