Abstract

Purpose

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been identified as the cause of the increasing oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) incidence in some countries. To investigate whether this represents a global phenomenon, we evaluated incidence trends for OPCs and oral cavity cancers (OCCs) in 23 countries across four continents.

Methods

We used data from the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents database Volumes VI to IX (years 1983 to 2002). Using age-period-cohort modeling, incidence trends for OPCs were compared with those of OCCs and lung cancers to delineate the potential role of HPV vis-à-vis smoking on incidence trends. Analyses were country specific and sex specific.

Results

OPC incidence significantly increased during 1983 to 2002 predominantly in economically developed countries. Among men, OPC incidence significantly increased in the United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, and Slovakia, despite nonsignificant or significantly decreasing incidence of OCCs. In contrast, among women, in all countries with increasing OPC incidence (Denmark, Estonia, France, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, and United Kingdom), there was a concomitant increase in incidence of OCCs. Although increasing OPC incidence among men was accompanied by decreasing lung cancer incidence, increasing incidence among women was generally accompanied by increasing lung cancer incidence. The magnitude of increase in OPC incidence among men was significantly higher at younger ages (< 60 years) than older ages in the United States, Australia, Canada, Slovakia, Denmark, and United Kingdom.

Conclusion

OPC incidence significantly increased during 1983 to 2002 predominantly in developed countries and at younger ages. These results underscore a potential role for HPV infection on increasing OPC incidence, particularly among men.

INTRODUCTION

Cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx are among the most common cancers worldwide, with an estimated 400,000 incident cases and 223,000 deaths during 2008.1 Tobacco and alcohol are strong risk factors for both oral cavity cancers (OCC) and oropharyngeal cancers (OPC).2,3 In contrast, the association of human papillomavirus (HPV) is heterogeneous; HPV is an established cause of OPC (including the tonsil, base of the tongue, and other parts of the pharynx)4,5 whereas its etiologic role in OCC is unclear.5–7

The incidence of OCC has declined in recent years in most parts of the world, consistent with declines in tobacco use.8,9 In contrast, OPC incidence has increased over the last 20 years in several countries,10–13 including Australia,14 Canada,15 Denmark,16 the Netherlands,17 Norway,18 Sweden,19 the United States,20 and the United Kingdom.21 These divergent incidence patterns for OCC and OPC led to the hypothesis that an exposure other than tobacco, perhaps HPV infection, was responsible for increasing OPC incidence. Consistent with this hypothesis, subsequent molecular studies in Australia,14 Sweden,19 and the United States22 reported dramatic increases in the proportion of HPV-positive OPCs since the 1980s, particularly among men and individuals younger than age 60 years.

These observations highlight the utility of comparisons of incidence trends between OCC and OPC to evaluate the potential impact of HPV, particularly in geographic regions without historical data on HPV prevalence in oropharynx tumors. Although characterized as a virus-related epidemic,10,11 given the predominantly country-specific nature of recent publications, it is unclear whether increasing OPC incidence overall as well as in subgroups (eg, men) is a global phenomenon or whether it is restricted to certain countries.

Understanding the burden of HPV-associated OPC worldwide could have important implications for prevention, potentially through prophylactic HPV vaccination, and could inform male vaccination policy. Therefore, we evaluated global patterns in incidence trends for OCC and OPC by using cancer registry data from 23 countries across four continents. We compared and contrasted incidence trends for OPC with those of OCC and lung squamous cell carcinomas to understand the impact of HPV vis-à-vis smoking on observed incidence patterns.

METHODS

Data Sources

We used data from the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Volumes VI to IX (1983 to 2002) maintained by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.23 Each volume of CI5 compiles cancer incidence data from population-based, country-specific, or region-specific cancer registries. Cancers were coded according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). We included cancer incidence data by individual calendar year and 5-year age groups from 70 registries in 23 countries across four continents (Table 1), as follows: Asia—India, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand; Australia; Europe—Austria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, and United Kingdom; and North and South/Central America—Canada and United States (nine Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries), Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador. These registries were selected based on of having at least 15 years of data published in CI5 including the last volume, a marker of high-quality data given the stringent review process involved. United Nations definitions were used to classify countries as economically developed or developing.6

Table 1.

Description of Cancer Registries (1983 to 2002)

| Country | No. of Registries | Incidence Rate per 100,000 During 1998 to 2002, Standardized to the World Standard Population |

Available Age Range for Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropharyngeal Cancers* |

Oral Cavity Cancers† |

||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Asia | |||||||

| India | 2 | 9.1 | 1.8 | 16.4 | 10.6 | 25-79 | 25-79 |

| Japan | 2 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Philippines | 1 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 4.3 | 25-80 | 25-80 |

| Singapore | 2 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 25-84 | 25-84 |

| Thailand | 1 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 25-79 | 25-79 |

| Australia | 5 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Europe | |||||||

| Austria | 1 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Denmark | 1 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Estonia | 1 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 10.4 | 2.0 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| France | 8 | 17.8 | 2.7 | 15.6 | 3.8 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Italy | 7 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Poland | 2 | 5.2 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 1.9 | 25-84 | 25-84 |

| Slovakia | 1 | 15.4 | 0.8 | 15.2 | 1.5 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Spain | 5 | 5.7 | 0.4 | 9.8 | 2.7 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| Switzerland | 2 | 9.9 | 2.9 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 3.5 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| North America | |||||||

| Canada | 9 | 5.3 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

| United States | 9 | 7.3 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 4.2 | 25-84 | 25-84 |

| South and Central America | |||||||

| Brazil | 1 | 9.1 | 1.1 | 13.7 | 3.3 | 25-84 | 25-84 |

| Colombia/Costa Rica/Ecuador‡ | 3 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 25-89 | 25-89 |

Oropharyngeal cancer sites: base of tongue, lingual tonsil, tonsil, oropharynx, pharynx not otherwise specified, and Waldeyer ring.

Oral cavity cancer sites: oral tongue, gum, floor of mouth, palate, and other and unspecified parts of the mouth.

Registries in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador were combined for analyses because of sparse sample sizes.

Classification of Anatomic Sites

OPC sites included base of tongue (ICD-10 code C01), lingual tonsil (C2.4), tonsil (C9.0 to C9.9), oropharynx (C10.0 to C10.9), pharynx not otherwise specified (C14.0), and Waldeyer ring (C14.2). OCC sites included oral tongue (ICD-10 codes C2.0 to 2.3, C2.8, and C2.9), gum (C3.0 to C3.9), floor of mouth (C4.0 to C4.9), palate (C5.0 to C5.9), and other and unspecified parts of the mouth (C6.0 to C6.9).20 The following sites were excluded from all analyses: lip (ICD-10 code C00), salivary gland (C07 to C08), nasopharynx (C11), pyriform sinus (C12), and hypopharynx (C13). Results were similar when soft palate and uvula (C5.1 and C5.2, which are part of the oropharynx, but are not etiologically related to HPV infection) were included with OPC as well as when overlapping lesions (C14.0, C2.8, C2.9, and C5.9) were excluded from the respective oropharyngeal/oral categories (data not shown). All histologies were included. However, we note that an overwhelming majority (approximately 95%) of head and neck cancers are squamous cell histologies.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted separately among men and women. Country-specific analyses were conducted by combining data from all cancer registries within a country. Results were similar when country-specific analyses were restricted to registries with equal calendar period coverage (eg, Canada, United Kingdom; data not shown). We initially evaluated trends in age-standardized (world standard population24) OPC and OCC incidence by individual calendar year (1983 to 2002) using weighted least squares log-linear regression. These models incorporated cubic regression splines, and the number of segments/splines was selected based on the Akaike information criterion. Temporal trends were quantified through the estimated annual percent change, calculated as follows: (the antilog of the regression coefficient for calendar year − 1) × 100, as described by Kim et al.25

We used age-period-cohort modeling using 5-year age groups (25 to 29, 30 to 34, …, 80 to 84 years, varying by registry; Data Supplement), 5-year calendar periods (1983 to 1987, 1988 to 1992, …, and 1998 to 2002), and 10-year partially overlapping birth cohorts (midyear of birth, 1903, 1908, …, 1973, varying by registry) to simultaneously evaluate the effects of age, calendar year (period), and birth year (cohort) on incidence rates.26,27 From these models, we estimated the net drift parameter, which represents the net sum of the log-linear temporal trend arising from period effects and birth cohort effects. The interpretation of the net drift is analogous to that of the estimated annual percent change, but the net drift simultaneously adjusts for nonlinear birth cohort effects. To evaluate whether temporal trends significantly differed between OPCs and OCCs, we compared the respective net drifts using a 1-df Wald test.27

To evaluate whether changing incidence across calendar years was specific to certain age groups, we used age-period-cohort models to estimate age-specific net drifts, which were then compared with the global net drift using a Wald test for heterogeneity.27 In the age-period-cohort model, age-specific net drifts are a function of birth cohort effects. Furthermore, under the null hypothesis of no age interaction, all age-specific net drifts are equal to the global net drift.

In additional analyses, for each sex and country, we estimated net drifts for lung squamous cell carcinomas to evaluate the potential impact of trends in cigarette smoking on observed incidence patterns. The lung cancer net drifts were then statistically compared with the net drifts for OPCs and OCCs using a 1-df Wald test. To evaluate whether improved anatomic site classification over time could have led to increasing incidence, we assessed trends over time (5-year periods) in the proportion of OCCs and OPCs without an anatomic site specification (overlapping lesions of the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx [ICD-10 C14.8]). Temporal trends in incidence of OPC, OCC, and lung cancers and formal comparisons of temporal trends across OPC, OCC, and lung cancers were based on two-sided statistical tests, and P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The study included 182,736 OPCs and OCCs that occurred during 1983 to 2002 across 23 countries around the world, including 69,592 OPCs (54,700 among men and 14,892 among women) and 113,144 OCCs (74,771 among men and 38,373 among women). During the most recent calendar period (1998 to 2002), incidence of both OPCs and OCCs varied widely across countries (Table 1). Among men, the highest incidence of OPCs was observed in France, Slovakia, and Switzerland, whereas the highest incidence rates of OCCs were observed in India, France, Slovakia, and Brazil. Among women, the rates were two to 17 times lower than the rates in men, with highest OPC incidence in Switzerland, France, and Denmark and highest OCC incidence in India, the Philippines, and Denmark/France/Switzerland.

Incidence Trends Among Men (1983 to 2002)

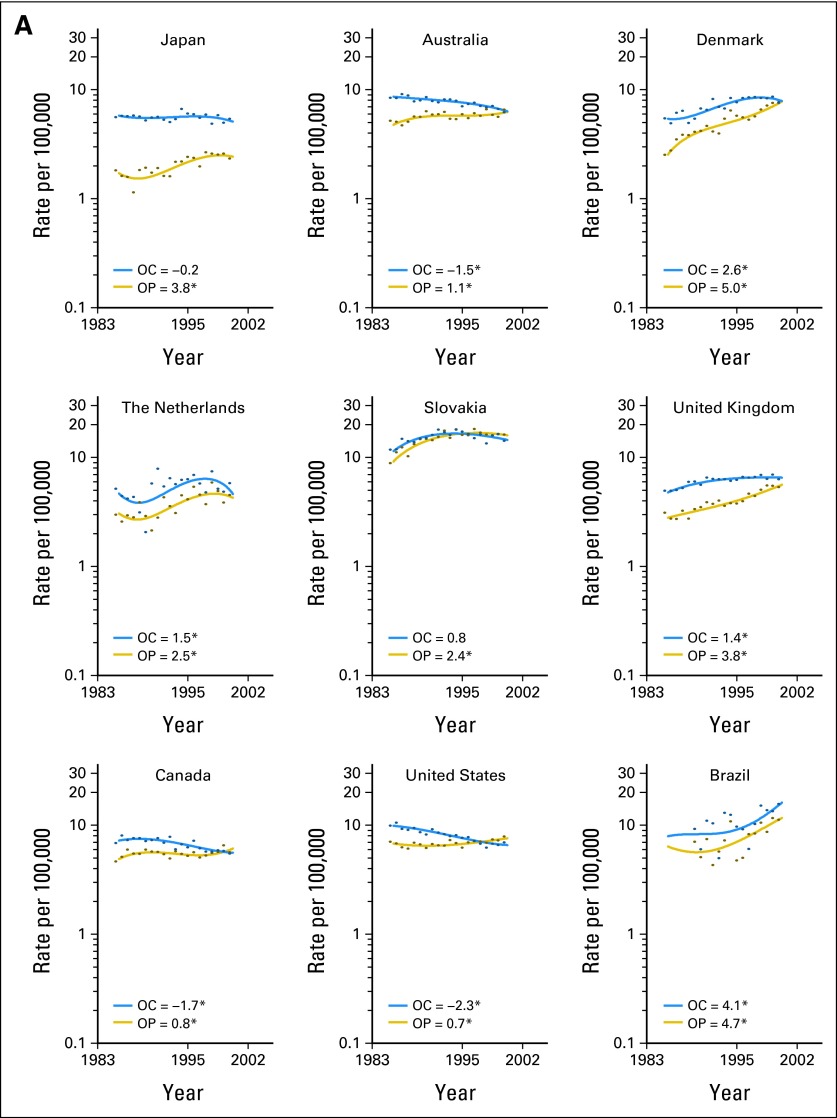

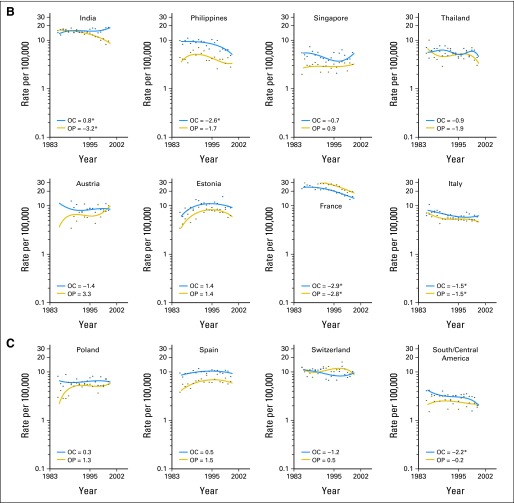

Among men, significant increases in OPC incidence during 1983 to 2002 were observed predominantly in economically developed countries (Fig 1A; Japan, Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Slovakia, United Kingdom, Canada, United States, and Brazil). No significant increases in OPC incidence were observed (Fig 1B-C) in economically developing countries in South/Central America (Colombia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador) and Asia (India, the Philippines, and Thailand). For OCC (Figs 1A-1C), incidence increased significantly during 1983 to 2002 in Denmark, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Brazil, and India.

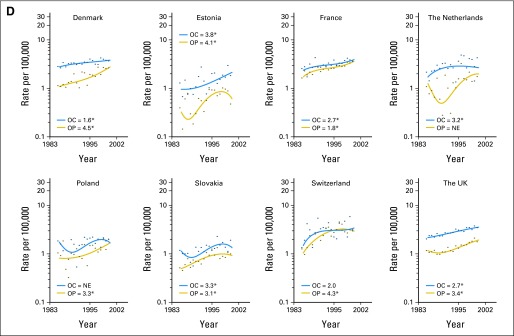

Fig 1.

Incidence trends for oropharyngeal (OP) cancers (shown in gold) and oral cavity (OC) cancers (shown in blue). Results are shown for (A) countries with significantly increasing OP cancer incidence among men. For all parts of Figure 1, filled circles represent observed incidence rates, and solid lines represent fitted incidence rates. The key in each graph shows estimated annual percent changes (EAPCs) in incidence during 1983 to 2002, which were calculated using weighted least squares log-linear regression. (*) EAPC statistically significant at P < .05. NE, not estimable. Results are shown for (B, C) countries with nonsignificant trends or significant declines in OP cancer incidence among men. Results are shown for (D) countries with significantly increasing OP cancer incidence among women. Results are shown for (E, F) countries with nonsignificant trends or significant declines in OP cancer incidence among women.

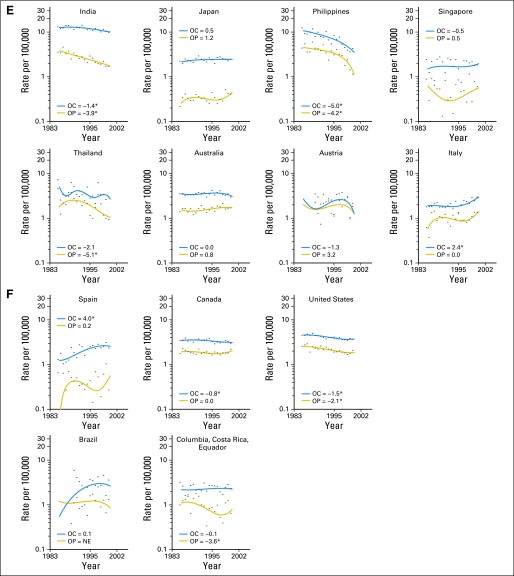

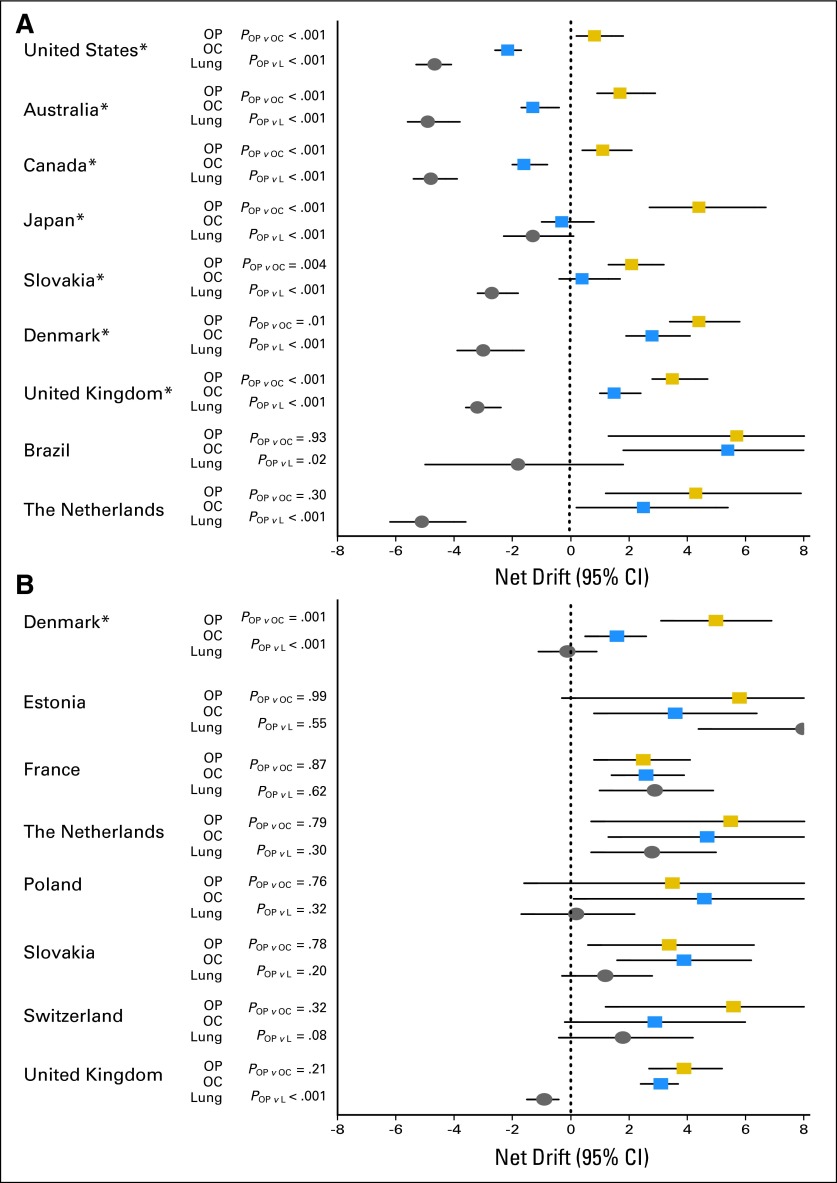

Comparisons of incidence trends between OPC and OCC using age-period-cohort modeling showed the following three prominent patterns (Fig 2A): countries with statistically significant divergent trends, with significant increases in OPC incidence and nonsignificant trends or significant declines in OCC incidence (United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, and Slovakia); countries with significant increases in incidence for both OPC and OCC but statistically significantly stronger increases for OPC (Denmark and United Kingdom); and countries with statistically similar incidence trends for OPC and OCC (Brazil and the Netherlands). With the exception of India, no significant differences in incidence trends between OPC and OCC were observed in countries with nonsignificant trends or significantly decreasing trends in OPC incidence (Data Supplement).

Fig 2.

The net drifts and 95% CIs from age-period-cohort models are shown for oropharyngeal (OP) cancers (gold squares), oral cavity (OC) cancers (blue squares), and lung cancers (gray circles). Results are shown separately for (A) men and (B) women. The net drift represents the net sum of the linear trend in period and cohort effects. P values for the comparison of net drifts for OP versus OC cancers, as well as for comparisons of OP versus lung (L) cancer, are also shown in each panel. Results are presented for countries with significant increases in OP cancer incidence. Results for all other countries are presented in the Data Supplement. (*) Countries with significant differences between OP versus OC cancers. UK, United Kingdom.

Comparisons of OPC incidence with lung cancer incidence revealed statistically significant divergent patterns (Fig 2A). With the exception of Brazil, where incidence trends were nonsignificant, lung cancer incidence significantly declined in all other countries with significant increases in OPC incidence (United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, Slovakia, Denmark, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands).

Substantial increases in OPC were observed among younger birth cohorts in most countries with significantly increasing overall incidence, resulting in the increasing incidence being statistically significantly stronger at ages younger than 60 years (Data Supplement; United States, Australia, Canada, Slovakia, Denmark, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands; P < .05 for heterogeneity of net drifts). For OCC, a similar statistically significant increase at younger ages was observed only in the United Kingdom, whereas incidence decreased significantly at younger ages in the United States, Australia, and Canada.

Incidence Trends Among Women (1983 to 2002)

Among women, significant increases in OPC incidence were observed exclusively in European countries (Denmark, Estonia, France, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, and United Kingdom; Fig 1D). Likewise, OCC incidence significantly increased during 1983 to 2002 in Europe (Denmark, Estonia, France, the Netherlands, Slovakia, United Kingdom, Italy, and Spain; Figs 1E and 1F).

In contrast to the divergent patterns observed among men, incidence trends for OPC and OCC were statistically similar in a majority of countries among women. With the exception of Denmark, in all other countries with significant increases in OPC incidence among women (France, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Switzerland, and United Kingdom; Fig 2B), incidence of OCC also increased significantly. In Denmark, the magnitude of the increase for OPC was significantly stronger than the increase for OCC. With the exception of India, no significant differences in incidence trends between OPC and OCC were observed among women in countries with nonsignificant trends or significantly decreasing trends in OPC incidence (Data Supplement).

Comparisons of OPC incidence with lung cancer incidence among women again indicated the lack of statistically divergent incidence patterns (Fig 2B). In almost all countries with significant increases in OPC incidence, lung cancer incidence increased either significantly (France and the Netherlands) or nonsignificantly (Denmark, Slovakia, and Switzerland). An exception to this general phenomenon was the United Kingdom, where OPC incidence significantly increased despite significant declines in lung cancer incidence.

We observed evidence for birth cohort effects in a few countries with significant increases in OPC incidence among women (Data Supplement). Significantly stronger increases in OPC incidence at ages less than 60 years were observed in France, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom. For OCC, significantly stronger increases at younger ages were observed in France and Slovakia.

Indices of Data Quality Across CI5 Volumes VI to IX

The combined proportion of OCCs and OPCs classified as other, ill-defined sites in the oral cavity and pharynx generally decreased over calendar time. Nonetheless, across CI5 volumes, less than 4% of these cancers were classified as ill-defined (Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

In a comprehensive analysis of worldwide trends in incidence of OPC and OCC, our key observation was that incidence of OPC significantly increased during 1983 to 2002 in several countries around the world. Notably, increasing OPC incidence was most apparent in a number of developed countries, among both men and women and in younger individuals (age < 60 years). Our results underscore the potential for increasing global relevance of HPV as a cause of OPC.

We exploited the etiologic heterogeneity in HPV's association with OPC versus OCC to evaluate the potential impact of HPV versus smoking on observed incidence trends. We interpreted two statistically significant patterns as indicative of a dominant role for HPV on the observed incidence trends—significantly increasing incidence for OPC, accompanied by nonsignificant trends or significant declines in incidence for OCC; and a statistically stronger increase in incidence of OPC compared with OCC. In contrast, increasing incidence of both OPC and OCC to a statistically similar magnitude was interpreted as a potential effect of tobacco use/smoking. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by evaluating trends in lung squamous cell carcinomas, a cancer strongly related to smoking.

Using this paradigm, we identified countries in which HPV infection potentially contributed to increasing OPC incidence; these countries were the United States, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Slovakia, and United Kingdom among men and Denmark among women. Notably, lung cancer incidence significantly declined during the same period among men in the United States, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Slovakia, and United Kingdom, and lung cancer incidence was stable among women in Denmark. These observations suggest a role for a factor other than smoking, notably HPV infection, as a potential explanation for increasing OPC incidence.

Increases in OPC incidence during 1983 to 2002 were observed almost exclusively in economically developed countries. For example, eight of nine countries among men and all countries among women with significant increases in OPC incidence were economically developed. This specific increase in economically developed countries likely reflects geographic differences in sexual behaviors relevant for oral HPV exposure (eg, oral sex and multiple sex partners). Using cancer registry data and HPV prevalence in tumors, recent studies in Australia,14 Sweden,19 and the United States22 have suggested that changes in sexual behaviors among recent birth cohorts have led to increased oral HPV exposure and, as a consequence, increasing incidence of OPC. It is likely that these changes in sexual behaviors have occurred predominantly in more developed countries than in less developed countries.14,28 Furthermore, consistent with the hypothesis of changes in sexual behaviors among recent birth cohorts, in a majority of countries with increasing OPC incidence among men (United States, Australia, Canada, Slovakia, Denmark, and United Kingdom), the increase was most apparent in those younger than age 60 years.

Although published data are sparse, reports of HPV prevalence in oropharynx tumors also support a dominant role for HPV in economically developed versus developing countries.29 For example, contemporary estimates indicate that approximately 60% to 70% of OPCs are caused by HPV infection in the United States,4,22,30 compared with less than 10% in less economically developed regions.29,31 Similarly, in a comprehensive review of the global burden of infection-associated cancers, de Martel et al6 recently estimated that HPV infection accounted for 38% to 56% of OPCs in Australia, Japan, North American, and Northern and Western Europe compared with 13% to 17% of OPCs in other parts of the world.

Our results suggest significant sex differences in the potential impact of HPV on incidence trends for OPC. OPC incidence significantly increased in several countries among men, despite nonsignificant trends or significant declines in incidence of OCCs and lung cancers. In contrast, in all countries with significant increases in OPC incidence among women, there was a concomitant increase in incidence of both OCCs and lung cancers. These results suggest that smoking could partially explain the increasing OPC incidence observed among women. However, we note the possibility that a potential effect of HPV among women could have been masked by smoking-related increases in OPC incidence.

Our observation of a potentially stronger role for HPV on increasing OPC incidence among men is supported by higher prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal tumors among men compared with women in some geographic regions. For example, in a recent study of tumors collected by population-based cancer registries in the United States, HPV prevalence was significantly higher among men compared with women.22 This male predominance is also supported by higher oral HPV prevalence among men than women in the US general population.32

We observed a significant increase in OCC incidence despite significant declines in lung cancer incidence in Brazil, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom among men and in the United Kingdom among women. We could not attribute this increase in OCC incidence to HPV infection (given current etiologic understanding), smoking (given lung cancer incidence trends noted herein), or improved data quality over time (given historically low proportions of ill-defined sites). An alternative explanation for increasing OCC (as well as OPC) incidence could be an increase among recent birth cohorts in alcohol use,8 which interacts with smoking multiplicatively to increase risk of both OCC and OPC. Likewise, the prevalence of chewing tobacco, another strong risk factor for both OCC and OPC, could also have increased among recent birth cohorts.29,33 Although data are sparse, it is possible that migration of populations from regions with an elevated incidence of head and neck cancer could also have contributed to increasing OCC and OPC incidence in some countries.34,35

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. Importantly, we did not have information on HPV status of tumor tissues or on other important risk factors, such as chewing tobacco, smoking, and alcohol use. We statistically compared and contrasted incidence trends across OPCs, OCCs, and lung cancers to delineate the potential influence of HPV infection versus smoking on observed incidence trends. However, these comparisons are ecologic in nature and should be interpreted with caution. Finally, despite the inclusion of 23 countries in our study, our analyses were restricted by the availability of high-quality cancer registry data and thus included a minor proportion of the worldwide burden of OCC and OPC.

Our observations of increasing OPC incidence in several countries around the world have important research and public health implications. The reasons underlying a male predominance of HPV's potential role on observed incidence trends are currently unclear and need confirmation and further investigation. This male predominance also has important implications for male HPV vaccination policy in several countries. If proven efficacious, prophylactic HPV vaccines could be an effective primary prevention strategy for HPV-associated OPCs among men,36 particularly in countries with low vaccine coverage among women.37 However, tobacco and alcohol use remain the major risk factors for both OPC and OCC worldwide,33 and the burden of OCC remains two- to four-fold higher than that of OPC in most parts of the world, underscoring the need for prevention strategies targeted toward tobacco and alcohol use.

Supplementary Material

Glossary Terms

- Akaike information criterion:

Measure of the goodness of fit of a statistical model that discourages overfitting and is used as a tool for model selection. For a given data set, competing models are ranked according to their Akaike information criterion value, and the one with the lowest value is considered the best. However, there is no established value above which a given model is rejected.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Cancer Institute and by a grant from the Institut National du Cancer (SPLIT project Grant No. 2011/196).

Terms in blue are defined in the glossary, found at the end of this article and online at www.jco.org.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Maura L. Gillison, GlaxoSmithKline (C), Bristol-Myers Squibb (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Patents: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Anil K. Chaturvedi, William F. Anderson, Maura L. Gillison

Financial support: Anil K. Chaturvedi

Administrative support: Anil K. Chaturvedi

Collection and assembly of data: William F. Anderson, Joannie Lortet-Tieulent, Jacques Ferlay, Silvia Franceschi, Freddie Bray

Data analysis and interpretation: Anil K. Chaturvedi, William F. Anderson, Joannie Lortet-Tieulent, Maria Paula Curado, Jacques Ferlay, Silvia Franceschi, Philip S. Rosenberg, Freddie Bray, Maura L. Gillison

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–615. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingen MW, Xiao W, Schmitt A, et al. Low etiologic fraction for high-risk human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franceschi S, Bidoli E, Herrero R, et al. Comparison of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx worldwide: Etiological clues. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:106–115. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blot WJ, Devesa SS, McLaughlin JK, et al. Oral and pharyngeal cancers. Cancer Surv. 1994;19–20:23–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marur S, D'Souza G, Westra WH, et al. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: A virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:781–789. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramqvist T, Dalianis T. Oropharyngeal cancer epidemic and human papillomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1671–1677. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaturvedi AK. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of HPV in head and neck cancers. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(suppl 1):S16–S24. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillison ML, Alemany L, Snijders PJ, et al. Human papillomavirus and diseases of the upper airway: Head and neck cancer and respiratory papillomatosis. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F34–F54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong AM, Grulich AE, Jones D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx in Australian males induced by human papillomavirus vaccine targets. Vaccine. 2010;28:3269–3272. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auluck A, Hislop G, Bajdik C, et al. Trends in oropharyngeal and oral cavity cancer incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related and HPV-unrelated sites in a multicultural population: The British Columbia experience. Cancer. 2010;116:2635–2644. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blomberg M, Nielsen A, Munk C, et al. Trends in head and neck cancer incidence in Denmark, 1978-2007: Focus on human papillomavirus associated sites. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:733–741. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braakhuis BJ, Visser O, Leemans CR. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the Netherlands between 1989 and 2006: Increasing incidence, but not in young adults. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:e85–e89. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mork J, Møller B, Dahl T, et al. Time trends in pharyngeal cancer incidence in Norway 1981-2005: A subsite analysis based on a reabstraction and recoding of registered cases. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1397–1405. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammarstedt L, Lindquist D, Dahlstrand H, et al. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2620–2623. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, et al. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy VM, Cundall-Curry D, Bridger MW. Trends in the incidence rates of tonsil and base of tongue cancer in England, 1985-2006. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:655–659. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12699663904871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Volumes I to IX: IARC CancerBase No. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doll R, Payne P, Waterhouse J. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1996. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents: A Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. II: Age-period-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987;6:469–481. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Age-period-cohort models in cancer surveillance research: Ready for prime time? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1263–1268. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehtinen M, Kaasila M, Pasanen K, et al. Seroprevalence atlas of infections with oncogenic and non-oncogenic human papillomaviruses in Finland in the 1980s and 1990s. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2612–2619. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: The International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribeiro KB, Levi JE, Pawlita M, et al. Low human papillomavirus prevalence in head and neck cancer: Results from two large case-control studies in high-incidence regions. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:489–502. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambert R, Sauvaget C, de Camargo Cancela M, et al. Epidemiology of cancer from the oral cavity and oropharynx. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:633–641. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283484795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW, Linklater KM, et al. Cancer of mouth, pharynx and nasopharynx in Asian and Chinese immigrants resident in Thames regions. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:471–475. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangtani P, Maringe C, Rachet B, et al. Cancer mortality in ethnic South Asian migrants in England and Wales (1993-2003): Patterns in the overall population and in first and subsequent generations. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1438–1443. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Reducing HPV-associated cancer globally. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:18–23. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brisson M, van de Velde N, Franco EL, et al. Incremental impact of adding boys to current human papillomavirus vaccination programs: Role of herd immunity. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:372–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.