Abstract

Anthroposophic medicine is an integrative multimodal treatment system based on a holistic understanding of man and nature and of disease and treatment. It builds on a concept of four levels of formative forces and on the model of a three-fold human constitution. Anthroposophic medicine is integrated with conventional medicine in large hospitals and medical practices. It applies medicines derived from plants, minerals, and animals; art therapy, eurythmy therapy, and rhythmical massage; counseling; psychotherapy; and specific nursing techniques such as external embrocation. Anthroposophic healthcare is provided by medical doctors, therapists, and nurses. A Health-Technology Assessment Report and its recent update identified 265 clinical studies on the efficacy and effectiveness of anthroposophic medicine. The outcomes were described as predominantly positive. These studies as well as a variety of specific safety studies found no major risk but good tolerability. Economic analyses found a favorable cost structure. Patients report high satisfaction with anthroposophic healthcare.

Key Words: Anthroposophic medicine, integrative, patient-centered, holistic

摘要

人智医学是一种综合性的多模式治疗体系,它建立在对人类与大自然,以及对病症和治疗的整体理解之上。其基础为四层构成力概念和三重人体体质模型。在大型医院以及实际的医疗实践中,人智医学与传统医学是结合在一起使用的。它采用从植物、矿物和动物中提取的药物;采用艺术疗法、精神疗法和节律性按摩;采用咨询、心理治疗和特种护理技术,比如外用搽剂等。人智医疗由医生、治疗师和护士提供。一项卫生技术评估报告及其最近的更新文档列举了 265 项针对人智医学效用和效益的临床研究。其研究结果被阐述为这种疗法具有压倒性的正面优势。这些研究以及其他各种特定的安全性研究并没有发现其重大的风险,而是提示具有很好的耐受性。经济分析也发现它具有有利的成本构 成。人智医疗在患者报告中获得 了很高的满意度。

SINOPSIS

La medicina antroposófica es un sistema de tratamiento multimodal integrador que se basa en un entendimiento holístico del hombre y la naturaleza, así como de la enfermedad y del tratamiento. Se desarrolla sobre un concepto de cuatro niveles de fuerzas formativas y sobre el modelo de una constitución humana en tres partes. La medicina antroposófica se integra con la medicina convencional en grandes hospitales y en consultorios médicos. Aplica medicamentos de origen vegetal, mineral y animal; terapias artísticas, euritmia curativa y masaje rítmico; orientación, psicoterapia y técnicas de enfermería específicas, tales como la frotación externa. La atención sanitaria antroposófica es realizada por médicos, terapeutas y personal de enfermería. En un informe de evaluación de la tecnología sanitaria y en su reciente actualización se identificaron 265 estudios clínicos sobre la eficacia y la efectividad de la medicina antroposófica. Los resultados se describieron como predominantemente positivos. Estos estudios, así como diversos estudios de seguridad específicos, no encontraron ningún riesgo importante y sí una buena tolerabilidad. Los análisis económicos revelaron una estructura de costes favorable. Los pacientes indican una alta satisfacción con la atención sanitaria antroposófica.

Anthroposophic medicine is an integrative medical system, an extension of conventional medicine incorporating a holistic approach to man and nature and to illness and healing. It was founded in the early 1920s by Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman. It is established in 80 countries worldwide, most significantly in Central Europe. It is practiced by physicians, therapists, and nurses and provides specific treatments and therapies including medication, art, movement, and massage therapies and specific nursing techniques. The entire range of all acute and chronic diseases is being treated, with a focus on children's diseases, family medicine, and particularly chronic diseases necessitating long-time complex treatments. Patients are highly satisfied with this holistic form of healthcare.

ANTHROPOSOPHY AS A SPIRITUAL SCIENCE

Anthroposophic medicine is based on the cognitive methods and cognitive results of anthroposophy.1 Anthroposophy was established by Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925).2 After studying empirical sciences, mathematics, and philosophy in Vienna, Steiner was commissioned at the age of 22 to publish Johann Wolfgang Goethe's scientific writings in Kürschners Deutscher Nationalliteratur (German National Literature) and collaborated on the Sophie Edition of Goethe's works in Weimar.3,4 Steiner began developing anthroposophy in 1901.5 Anthroposophy is a view on humanity and nature that is spiritual and that at the same time regards itself to be profoundly scientific.6 Steiner considered anthroposophy a consequential evolutionary step in the development of Western thought.7 In anthroposophy, three traditions are integrated and enhanced: the empirical tradition of modern science as started by Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo; the cognitional tradition of philosophy as initiated by Plato and Aristotle and as brought to a culmination in so-called German idealism by Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Schiller and Goethe; and finally the esoteric tradition of Christian spirituality. The stability of this integration was reflected in Steiner's critique and rejection of the philosophy of Kant8 and of materialistic reductionism.3 Kant had propagated the idea that there were definite limitations to scientific knowledge,9 and the materialistic reductionism movement had declared the interactions of material particles to be the basic principle of all scientific explanation.10–12 In contrast, Steiner proposed and described how human beings could expand their cognitive capacities and how these expanded capacities6 could be implied to investigate a variety of formative forces that are, beyond particle interactions, effective in organisms (Sidebar 1).13

Sidebar 1. Anthroposophic Concept of the Human Organism and Pathogenesis.

The Four-level Concept of Formative Forces13

The anthroposophic concept of the human being claims that the human organism is not only formed by physical (cellular, molecular) forces but by a total of four levels of formative forces: (1) formative physical forces; (2) formative growth forces that interact with physical forces and bring about and maintain the living form, as in plants; (3) a further class of formative forces (anima, soul) that interact with the growth forces and physical forces, creating the duality of internal-external and the sensory, motor, nervous and circulatory systems as seen in animals; (4) an additional class of formative forces (Geist, spirit) that interacts with the three others and supports the expression of the individual mind and the capacity for reflective thinking, which is unique for humans.

The Three-fold Model of the Human Constitution14,15

When the four levels of formative forces are integrated with the human polarity of active motor movement and passive sensory perception, the three-fold constitution of the human being comes into being. It embraces three major systems: two being polar to each other (nerve-sense system and motor-metabolic system), and one being intermediate (rhythmic system). These subsystems are spread over the entire organism but predominate in certain regions: the nerve-sense system in the head region, the motor-metabolic system in the limb region, the rhythmic system in the respiratory and circulatory organs and thus in the “middle” region.

In these three subsystems, the four levels of formative forces are considered to interrelate differently. In the nerve-sense system, the upper two levels of forces (spirit, soul) are relatively separate from the lower two levels, thus providing the conditions for the origination of self-consciousness, conscious perceptions, and conscious thought processes. In the motor-metabolic system, the interpenetration is closer, thus providing the conditions for the execution of personally intended bodily movements. In the rhythmic system, the interrelations of the upper and lower levels fluctuate between increasing and decreasing connection and are associated with the origination of emotion; the interpenetration increases during the rhythmical lung process of inspiration and decreases during expiration.

The model of the three-fold human constitution leads to distinct re-interpretations of the conventional teachings of physiology.

The concept of a multilevel organism with diverse subsystems is compatible with modern system approaches in developmental biology and with holistic models of cancer.16–18 In anthroposophy, the concept of the formative forces is rather elaborate and is also accompanied by a corresponding concept of material matter. The physical structures of matter are considered only one level, and when a substance is absorbed into the context of an organism, the substance becomes “enlivened” or even “ensouled.”1 The investigation of the formative forces and their material correspondences and of the diverse interrelations among these forces provides the basis for the anthroposophic worldview. This view brings spiritual dimensions to the natural sciences.6

Steiner provided anthroposophy with a deeply reflected epistemology.3–5,7,8,19–21 On the other hand, anthroposophy has proven to be not only a philosophy or a new orientation in science but also to be practically applicable. It induced a large variety of developments in different fields: a School of Spiritual Science with various specialized sections, founded in 1924 in Dornach, Switzerland; a new method of education (Waldorf schools, also known as Rudolf Steiner schools), currently with more than 1000 schools and approximately 2000 kindergartens, home programs, child care centers, and preschools worldwide; the curative education movement, which currently has more than 600 centers for curative education and social therapy worldwide for children, young people, and adults with disabilities and developmental problems; a new direction in agriculture, biodynamic farming; the creation of an art of movement, eurythmy; a renewal of various artistic practices such as recitation, dramatic art, painting, sculpture, and architecture; and attempts to reshape social life (three-fold social order22,23). One anthroposophic enterprise, Sekem, in Egypt,24 has been honored with the alternative Nobel Prize and with the Schwab Foundation Prize. Anthroposophic insights have been integrated into modern culture; numerous people in public life, commerce, banking, politics, culture, theatre and film, literature, the fine arts, music, fashion, and medicine have emerged from the anthroposophic scene.

BASIC PERSPECTIVES OF ANTHROPOSOPHIC MEDICINE

The etiologies and pathogeneses of diseases are concretely understood as abnormal interactions among the different levels of the human organism and its three subsystems (Sidebar 1).25,26 Reflecting upon these interactions is the basis for specific anthroposophic medical and treatment schedules. An example of such a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure has recently been outlined in a case report on anxiety and eurythmy therapy.27

Another basic aspect comes from the following: Once the existence and effectiveness of formative forces are taken into account, another view on the evolution of humanity and nature emerges, with specific relationships between the generating processes of the forms and substances in external nature and in the human body. Pathological deviations in the human organism can thus be seen in correspondence with formative processes and substances in nature. These correspondences are like those between keys and keyholes. Such or similar relations have been recognized in all cultures, even in humanity's earliest times. Assessing these relationships can enable rational medicinal therapies.1

Guiding principles of anthroposophic healthcare are recognizing the autonomy and dignity of the patient and helping people to help themselves. Self-responsibility is addressed, and therapeutic goals are to stimulate different forms of self-healing—to stimulate hygiogenesis,28 which means to create a coherent autonomic regulation of the organism; and salutogenesis,29 which means to create a coherent psycho-emotional and spiritual self-regulation.30 The treatments do not merely intend to restore a former healthy condition, a “restitution ad integrum,” but to provoke a new level of the organism's and the individual's inner strength.13

Anthroposophic medicine thus pursues a holistic approach. Rather than focusing on a singular pathological datum, the aim is to strengthen the whole constitution of the sick patient, taking into account all dimensions: physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and social. Treatments therefore often are multimodal. They are individually tailored in an attempt to synergize the effects of the different therapeutic components and so to enhance the chances for health improvement. Such treatment is conceived as a therapeutic system.31–33

PRACTICE AND FACILITIES OF ANTHROPOSOPHIC MEDICINE

Anthroposophic medicine is practiced in both inpatient and outpatient settings by trained medical doctors. Currently there are approximately 24 anthroposophic medical institutions, which include hospitals, departments in hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and other inpatient healthcare centers in Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, The Netherlands, and the United States (Sidebars 2 and 3 and Figure 1). In Germany, three large anthroposophic hospitals provide accident and emergency services within the requirement plans of the German Federal States (Bundesländer); two of them are academic teaching hospitals linked to neighboring universities (Sidebar 3). They provide specialty training for physicians. In 1983, the first private, nonstate university in Germany was founded out of one of these hospitals (University of Witten/Herdecke). In addition to the anthroposophic hospitals, there are more than 180 anthroposophic outpatient clinics worldwide in which anthroposophic physicians and therapists work together. Anthroposophic physicians also work in their own practices. Additionally, a variety of outpatient departments at large hospitals provide anthroposophic healthcare and consultation service (eg, Center for Integrative Medicine, Cantonal Hospital St Gallen, Switzerland; Institute of Complementary Medicine, University of Berne, Switzerland; Center for Complementary Medicine, University of Freiburg, Germany). Practitioners of anthroposophic medicine were decisively involved in the implementation of the liberal and pluralistic healthcare in Germany and in the relevant formulation of the German Medicines Act in 1976. Since 1976, anthroposophic medicine in Germany has been defined, alongside homeopathy and phytotherapy, as a distinct “special therapy system” (besondere Therapierichtung) in the Medicines Act34 and is represented in Germany by its own committee at the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. Also, Switzerland and Latvia have recognized anthroposophic medicine as a distinct therapy system. In some countries, legal recognition is restricted to pharmaceutical regulation. The authorization, registration, and supervision of the profession of anthroposophic doctors are delegated to national medical associations.

Sidebar 2. Anthroposophic Hospitals, Hospital Departments, Rehabilitation Centers.

Acute Hospitals

Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhöhe, D-Berlin (Sidebar 3)

Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, D-Herdecke (Sidebar 3)

Filderklinic, D-Filderstadt: Internal medicine, oncology, cardiology, gastroenterology, emergency and intensive care medicine, gynecology and obstetrics, pediatric medicine, pediatric psychiatry, neonatology, surgery, anesthesia, radiology, psychosomatic medicine

Ita Wegman Klinik, CH-Arlesheim: Internal medicine (with oncology, cardiology, neurology, respiratory medicine, geriatrics), psychiatry, psychosomatic medicine

Paracelsus-Spital, CH-Richterswil: Surgery, urology, internal medicine, oncology, gastroenterology, respiratory medicine, cardiology, gynecology and obstetrics, radiology, anesthesia, emergency department, palliative care

Vidarkliniken, S-Järna: Rehabilitation (cancer, stress-related diseases, chronic pain), palliative care (cancer)

Specialty Hospitals and Departments

Asklepios – West Hospital Hamburg, Center for Holistic Medicine, D-Hamburg: Internal medicine, psychosomatic medicine

Lahnhöhe Hospital, D-Lahnstein: Psychosomatic medicine

Öschelbronn Hospital, D-Öschelbronn: Internal medicine, oncology

Paracelsus Hospital, D-Bad Liebenzell-Unterlengenhardt: Internal medicine

Klinikum (Hospital) Heidenheim, D-Heidenheim: General medicine

Friedrich-Husemann-Klinik, D-Buchenbach: Psychiatry

Lukas Clinic, CH-Arlesheim: Integrative tumor therapy and supportive care

Hospital Emmental – Department of Complementary Medicine, CH-Langnau i.E.: General, oncology, palliative, and psychosomatic medicine.

Hospital Scuol – Department of Complementary Medicine, CH-Scuol: General, oncology, palliative and psychosomatic medicine, perioperative care

Lievegoed Klinik, NL-Bilthoven: Psychiatry

Rehabilitation and Other Inpatient Healthcare Centers

Alexander von Humboldt Klinik, D-Bad Steben: Geriatric rehabilitation center

Sanatorium Sonneneck, D-Badenweiler

Reha-Klinik Schloss Hamborn, D-Borchen über Paderborn

Haus am Stalten, D-Steinen

Höfe am Belchen, D-Kleines Wiesental – Neuenweg: Therapeutic Community for Children and Young Persons' Psychiatry

Heilstätte Sieben Zwerge, D-Salem-Oberstenweiler: Drug-related diseases,

Mutter und Kind Kurheim Alpenhof, D-Rettenberg

Casa di Cura Andrea Cristoforo, CH-Ascona

Casa die Salute Rapael, I-Roncegno (Trento)

Rudolf Steiner Health Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States: Therapy and training center for chronic illnesses

Abbreviations: CH, Switzerland (Confoederatio Helvetica); D, Germany (Deutschland); I: Italy; NL, Netherlands; S, Sweden.

Sidebar 3. Examples of Integrated Healthcare in Two Anthroposophic Hospitals.

Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, a tertiary care center and academic teaching hospital founded in 1969, is responsible for providing acute inpatient services for the town of Herdecke and its immediate and more distant surrounding areas, including emergency medical services (level II and level III care). Anthroposophic medical care—medication, nursing care, physiotherapy, therapeutic baths, rhythmical massage, therapeutic riding, ergotherapy, speech therapy, psychotherapy, eurythmy therapy, art therapies (using music, painting, sculpture, speech therapy)—is integrated into the following specialty departments:

Anesthesia, including pain therapy.

Surgery: general, abdominal, trauma surgery including endoprosthesis, plastic, vascular and thoracic, oncological surgery, minor pediatric surgical procedures.

Gynecology and obstetrics: approximately 900 births/year.

Interdisciplinary early rehabilitation.

Internal medicine: cardiology, gastroenterology, respiratory medicine, psychosomatic medicine.

Interdisciplinary oncology: ward, day clinic, outpatient department, patient counseling, psychooncology.

Pediatrics: pediatric diabetes and endocrinology, diabetes training, therapy center; neuropediatrics with a special focus on epilepsy with digital electroencephalogram (EEG), EEG monitoring, video EEG; developmental retardation services; pediatric oncology and hematology, collaboration with the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology; neonatology, pediatric intensive care medicine; pediatric and adolescent psychiatry, day hospital and secure ward with compulsory care, psychotraumatology (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, family therapy, psychosomatic medicine.

Neurology, including a department for spinal cord injuries, stroke, paraplegia.

Neurosurgery.

Emergency admission/intensive care medicine/intermediate care unit.

Adult psychiatry: acute and intensive care ward, secure ward with compulsory care, day hospital.

Radiology: x-ray, ultrasound, computer tomography, digital subtraction angiography, magnetic resonance imaging.

Various departments provide outpatient consultations and treatment.

Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhöhe, taken over in 1995 and reorganized as a hospital for anthroposophic medicine, is an acute hospital with 304 beds providing acute inpatient services for the surrounding area.

Anthroposophic medical care—including medication, nursing care, eurythmy therapy, art therapies (using music, painting, sculpting), rhythmical massage, massage using the Dr Pressel method, psychotherapy, physiotherapy, exercises, and manual lymph drainage—is integrated into the following specialty departments, with further interdisciplinary competence centers and interdisciplinary cooperation in the treatment of tumors:

Internal medicine: General, oncology, diabetes (with a diabetes education center, type I and II), gastroenterology (endoscopy: gastroscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ballon-enteroscopy, endosonography, all interventional therapeutic procedures—such as polypectomy, mucosectomy, sclerotherapy, banding, stenting, ultrasound-guided drainage, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration, pH determination in esophagus and stomach, manometry, multipolare radiofrequency—cardiology (invasive and noninvasive investigations including cardiac catheter laboratory, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, stent implantation, pacemakers, Havelhöhe Heart School).

Palliative ward and pain ward including port insertion, feeding catheters, stents, epidural catheters, pumps, neurolytic blocks.

Respiratory medicine, including whole body plethysmography, sleep apnea investigations, flexible video-bronchoscopy, thoracoscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, filling of pneumonectomy cavities, allergen provocation and challenge testing and hyposensitization, determining the indications for long-term and domestic oxygen therapy).

Surgery: general and oncological, visceral, hand, orthopedics, trauma, center for minimally invasive surgery including natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, vascular surgery, colorectal cancer center, outpatient and inpatient operations.

Gynecology and obstetrics (approximately 1200 births/year).

Breast center.

Drug withdrawal therapy (multiple drug users, heroin, alcohol).

Psychotherapeutic medicine, psychosomatic medicine.

Developmental pediatrics.

Anesthesia, including pain therapy.

Interdisciplinary intensive care ward, including hemodialysis.

Radiology, myelography, angiography, and computed tomography, nuclear medicine (single-photon emission computed tomography camera, myocardial scintigraphy, brain perfusion scintigraphy).

Various departments provide outpatient consultations. Fifty percent of the patients are from outside the region, which is regarded as a manifestation of high acceptance by patients. Havelhöhe Hospital is an academic teaching hospital of the Charité.

Figure 1.

Filderklinik, an anthroposophic hospital in Filderstadt, Germany. Source: Filderklinik; reprinted with permission.

Physicians

Anthroposophic medicine is practiced by physicians with specialized training in anthroposophic as well as conventional medicine, and anthroposophic therapies are also prescribed by many other physicians with varying levels of training. Anthroposophic physicians often work in primary care, but anthroposophic medicine is not limited to general practice. It also is practiced in more specialized realms (Figure 2; Sidebar 3).

Figure 2.

Anthroposophic physician performing surgery at an anthroposophic hospital. Source: Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhöhe; reprinted with permission.

The certification requirements to become an anthroposophic physician are defined and regulated on national levels, which share similar curriculum. In Germany, for instance, the curricula requires 3 years of postgraduate medical practice, 1 year's study of anthroposophic medicine according to a predefined program, and 2 years of medical practice under the guidance of a mentor. In addition, specific training courses are available in certain specialties. A further International Postgraduate Medical Training (IPMT) in anthroposophical medicine consists of a series of yearly week-long training and enables registered medical doctors to acquire a certificate of anthroposophic doctor after 3 years. Full curriculum training is available in several countries including Argentina, Australia, Austria, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, The Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and the United States. Several professorships for anthroposophic medicine exist, and postgraduate training is offered at a variety of universities/medical schools.

Guidelines for good professional practice set standards for anthroposophic physicians regarding ethical principles, training, certification, continuous medical education, professional conduct, relationship with colleagues and therapists, and social commitments. Internationally, anthroposophic physicians are represented by the International Federation of Anthroposophical Medical Associations (IVAA), which functions as an umbrella organization with regard to political and legal affairs.

ANTHROPOSOPHIC THERAPIES

Anthroposophic medicine employs, in addition to conventional treatments, special medications and special therapeutic procedures, including eurythmy therapy, rhythmical massage, anthroposophic art therapy, and counseling. In addition, there are special anthroposophic nursing techniques. The therapies can be used as monotherapy or combined with other anthroposophic therapies.

Medications

Plant, mineral, and animal substances are used in anthroposophic medications. Anthroposophic medications are conceived, developed, and produced in accordance with the anthroposophic knowledge of the human being, nature, and substance and are sometimes potentized. The method of production is specified in the German homeopathic pharmacopoeia, in the Swiss Pharmacopoeia, and in the Anthroposophic Pharmaceutical Codex and follows good manufacturing practice. The medications are administered orally, rectally, vaginally, parenterally (intracutaneously, subcutaneously, or intravenously), or topically (applied to the skin, conjunctival sac, or nasal cavity). Several pharmaceutical companies produce anthroposophic medicines (eg, Weleda, Arlesheim, Switzerland; Wala Heilmittel, Eckwälden, Germany; Abnoba Heilmittel, Pforzheim, Germany). In anthroposophic medical practice, homeopathic and herbal medicine preparations are also used, in addition to conventional pharmaceuticals if appropriate. The nonprofit, independent European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products (ESCAMP) investigates issues of system evaluation of anthroposophic medicine for regulatory purposes.

External Applications

External applications—such as embrocation, compresses (Figure 3), hydrotherapy, and medicinal baths—are used as elements of nursing care and therapy to stimulate, strengthen, or regulate hygiogenic processes. For this purpose, etheric or fatty oils, essences, tinctures, and ointments are used, as well as carbon dioxide in baths. Of particular importance is rhythmical massage (described below).

Figure 3.

Nursing packs. Source: Jürg Buess, Hiscia; reprinted with permission.

Nursing

In nursing care, the intention is to become acquainted with the whole patient and perceive the patient in his or her physical, psychological, and spiritual being. A caring bond is developed, which aims at developing a personal, accompanying, and mediating relationship with the patient. In affiliation with two anthroposophic hospitals (Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke and Filderklinik, Filderstadt; Sidebar 2) state-recognized training institutes provide 3-year courses in anthroposophically extended nursing. In addition, several institutions provide further training opportunities.

Art Therapy

Anthroposophic art therapy was developed mainly by Margarethe Hauschka,35 who also founded the first training institution for this form of therapy in 1962.36 Anthroposophic art therapy employs the following techniques:

Sculptural forming: Stone, soapstone, wood, clay, beeswax, plasticine, and sand are all used as sculpting materials.

Therapeutic drawing and painting: The materials used include paints and brushes, chalk, crayons, and paper.

Music therapy: Instruments used include percussion instruments such as the glockenspiel, xylophone, cymbals, resonant wooden blocks, drums and kettledrums; various wind instruments such as flute, crumhorn, shawm, trumpet, and alpenhorn; string instruments such as the chrotta (a simplified cello), violin, viola, and double-bass; and plucked instruments such as the harp, lyre and kantele. Melodies, sounds, and rhythms are improvised with the therapist or simply listened to. The choice of instrument depends on the individual circumstances of the patient, according to the severity and stage of the illness.

Anthroposophic speech therapy: This involves using articulation, consonants, vowels, text rhythms, and hexameters. Breathing plays a particular role in speaking (speech is formed exhalation). The indications for anthroposophic speech therapy are not only disorders of the voice but also general medical diseases, psychosomatic and psychiatric diseases, and learning and developmental difficulties.

Art therapy is provided as individual therapy, as individual therapy in small groups, or as group therapy. The patients learn to work specifically with the particular medium (such as painting or sculpture). Before the first treatment, there is a special session for obtaining an art-therapeutic anamnesis and diagnosis. Each succeeding therapy session usually lasts for 50 minutes and takes place once a week. Qualification as an anthroposophic art therapist requires 4 years' college training and a 2-year period of professional experience under a mentor. In Germany and The Netherlands, master of arts degrees are possible.

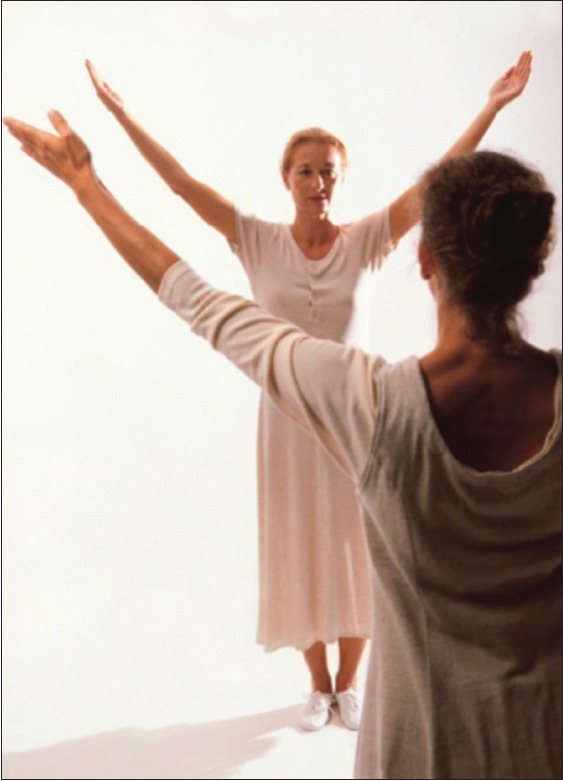

EURYTHMY THERAPY

Eurythmy therapy (In Greek, eurythmy means “harmonious rhythm”; Figure 4) is an exercise therapy involving cognitive, emotional, and volitional elements. It is provided by eurythmy therapists in individual or small group sessions during which patients are instructed to perform specific movements with the hands, the feet, or the whole body. Eurythmy therapy movements are related to the sounds of the vowels and consonants, to music intervals, or to soul gestures (eg sympathy-antipathy). For each patient, one movement is or several movements are selected depending on the patient's disease, his constitution, and on the therapist's observation of the patient's movement pattern.27 This selection is based on a core set of principles, prescribing specific movements for specific diseases, constitutional types, and movement patterns.37,38 A therapy cycle usually consists of 12 to 15 sessions, each usually lasting 30 to 45 minutes; between sessions, patients practice the exercises daily. Qualification as an eurythmy therapist requires 5 and a half years of training according to an international standardized curriculum. Eurythmy therapy is believed to have both general effects (eg, improving breathing patterns and posture, strengthening muscle tone, enhancing physical vitality39) and disease-specific effects.38

Figure 4.

Eurythmy therapy. Source: Professional Association for Eurythmy Therapy; reprinted with permission.

Rhythmical Massage

Rhythmical massage was developed from Swedish massage by Wegman, who was a physician and physiotherapist. Traditional massage techniques are augmented by lifting movements, rhythmically undulating or gliding movements, and complex movement patterns such as lemniscates and by using special loosening techniques from the deeper areas out to the periphery. In addition to effects on the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and muscles, rhythmical massage is believed to have both general effects (eg, enhancing physical vitality) and disease-specific effects. Rhythmical massage is practiced by physiotherapists with additional 1.5 to 3 years of rhythmical massage training according to a standardized curriculum.

Anthroposophic Psychotherapy and Counseling

Psychotherapy has been extended by anthroposophic perspectives to anthroposophic psychotherapy. Full training is available in different countries, and a master's/bachelor's degree in anthroposophic psychotherapy is available in Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Counseling on biographical-existential, lifestyle, nutritional, social, mental, and spiritual issues is a central element of anthroposophic medical care.

RESEARCH ON ANTHROPOSOPHIC MEDICINE

Since its development in the 1920s and early 1930s, anthroposophic medicine has been associated with extensive research activities. After World War II, when anthroposophic medicine was re-established in Europe, the focus was on founding practices, clinics, and hospitals rather than on research. In the 1970s and 1980s, research was again performed but also restrained by the predominant paradigm of the double-blind randomized trial, which is difficult to implement for nonpharmacological treatments, counseling, and whole system treatment. Randomization and blinding often have been rejected by anthroposophic physicians and their patients due to strong therapy preferences and the focus on the physician-patient relationship and highly individualized treatment approaches.40,41 During the past 30 years, research activities have grown steadily, including laboratory work, preclinical studies, clinical trials and observational studies, epidemiological research, safety assessments, economic analyses, patient's perspective assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and Health-Technology Assessment (HTA) reports. Intense work has been done on methodological issues, with a major focus on individualized therapy assessment, including systematic improvements of case report assessments.13 Research centers were set up at anthroposophic hospitals and universities. At present, research is particularly focused on the evaluation of the total system of anthroposophic medicine and, on the other hand, on individualized, personalized therapeutic approaches.

Clinical Efficacy and Effectiveness

The most comprehensive review of clinical efficacy and effectiveness of anthroposophic treatments—an HTA report and its update13,42—identified 265 studies. Thirty-eight of these studies were randomized controlled trials, 36 were prospective studies, and 49 were retrospective nonrandomized controlled studies. The remaining 142 studies were observational, without a comparison group.

The studies investigated a wide spectrum of anthroposophic treatments in a multitude of diseases: 38 evaluated the whole system of anthroposophic healthcare, 10 examined nonpharmacological therapies, 133 were devoted to anthroposophic mistletoe extracts in cancer, and 84 to other anthroposophic medication treatments. Methodological quality differed substantially; some studies showed major limitations and hardly allow valid conclusions regarding efficacy/effectiveness, while others were reasonably well-conducted.

Two-hundred fifty-three of the 265 studies (including 32 of the 38 randomized trials) described a positive outcome for anthroposophic treatments—meaning a comparable or a better result than with conventional treatment or a clinically relevant improvement of the condition, often in chronic disease and after unsuccessful conventional treatments. Twelve studies found no benefit, one of them with a negative trend. In one of these 12 studies,43 the standard treatment in the comparison group—intravesical instillation of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in superficial bladder cancer—was superior.

Mistletoe in Cancer.

Mistletoe treatment for cancer originated within anthroposophic medicine. It is one of the most commonly prescribed complementary cancer therapies in Central Europe44,45 and has been investigated intensely.46,47 Mistletoe (Viscum album L, not to be confused with Phoradendron, the American mistletoe) is a shrub that grows on different host trees. Extracts are made from specific parts of the plant (eg, fresh leafy shoots and berries). Anthroposophic mistletoe preparations (Abnobaviscum, Helixor, Iscador [labeled as “Iscar” in the United States], and Iscucin) are available from different host trees such as oak, apple, and pine. The harvesting procedure is standardized, and the juices from both summer and winter harvests are mixed together.

Mistletoe extract (ME) contains a variety of biologically active compounds,46,47 such as lectins, viscotoxins, other low molecular weight proteins, VisalbCBA (Viscum album chitin-binding agglutinin), oligo- and polysaccharides, flavonoids,48 vesicles,49 triterpene acids,50 and others. ME and several of its compounds are cytotoxic, and the lectins in particular have strong apoptosis-inducing effects.51–53 They also have an effect on multidrug-resistant cancer cells54 and enhance the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs.55,56 In mononuclear cells, ME possesses DNA-stabilizing properties. ME and its compounds stimulate the immune system (in vivo and in vitro activation of monocytes/macrophages, granulocytes, natural killer cells, T-cells, dendritic cells) and induce a variety of cytokines.46,47 The cytotoxicity of killer cells can also be markedly enhanced by a bridging effect through rhamnogalacturonans.57,58 Injected into tumor-bearing animals, ME and several of its compounds inhibit and reduce tumor growth.46,47 ME also enhances endorphins in vivo.46,47

Clinical studies on mistletoe in cancer describe rather consistently positive effects on quality of life: improved coping, sleep, appetite, energy, ability to work, and emotional and functional well-being, as well as reduced fatigue, exhaustion, nausea, vomiting, depression, and anxiety. Less consistently, the studies describe reduced pain and diarrhea.59 Regarding survival, study results were inconclusive until recently,60,61 and best evidence had rested mainly on epidemiological studies. A well conducted, large, randomized controlled trial has just been concluded; it investigated mistletoe therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who were not eligible for chemotherapy. The first interim analysis with 220 patients found a statistically significant benefit for survival (primary outcome parameter), with a median survival of 4.8 months in mistletoe-treated patients vs 2.7 months in control patients. Also, quality of life measured as a secondary outcome was superior regarding the functional scales and the symptoms of fatigue, sleep, pain, nausea, vomiting, and appetite. As expected, body weight decreased in control patients but increased in mistletoe-treated patients.62

Tumor remissions are rare in the common low-dose subcutaneous mistletoe therapy.60,61,63 However, they have repeatedly been described following local and high-dose applications of mistletoe extracts, eg, in liver cancer,64 pancreatic cancer,65 Merkel cell carcinoma,66 breast cancer,66 primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma,67 cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,68 and others.46,61 Local inflammatory response and fever often are observed at the beginning of treatment, and the tumor then regresses during the next couple of months.

Frequent side effects are dose-dependent local skin reactions and flu-like symptoms. Allergic reactions have been reported. Overall, mistletoe treatment is considered to be safe.13,46,69

System Evaluations.

The largest clinical studies on anthroposophic medicine were two system evaluations, together consisting of more than 2700 patients. The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS) is an observational cohort study of German outpatients treated for mental, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and other chronic conditions.70 One hundred fifty-one qualified anthroposophic physicians, 275 therapists, and 1631 patients aged 1 to 75 years participated. At study entry, patients had been ill for 3 years (median) or 6.5 years (mean). Following anthroposophic treatment (art therapy, rhythmical massage, eurythmy therapy, physician-provided counseling, anthroposophic medications), substantial and sustained improvements of disease symptoms and quality of life were observed. The improvements were found in adults70 and children71 in all therapy modality groups72–76 and in all evaluable diagnosis groups (anxiety disorders, asthma, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, low back pain, migraine77–83), and the effects were retained after 4 years. The improvements in quality of life were at least of the same order of magnitude as improvements following other (nonanthroposophic) treatments.84 In sensitivity analyses (combined bias suppression), maximally 37% of the improvement could be explained by natural recovery, regression to the mean, adjunctive therapies, and non-response bias.85 In a nested prospective nonrandomized comparative study, AMOS patients with low back pain had comparable or significantly more improvements than patients receiving conventional care.81

The International Integrative Primary Care Outcomes Study on anthroposophic medicine was conducted in four European countries and the United States and compared primary care patients who were treated by anthroposophic or conventional physicians for acute respiratory and ear infections. Compared to conventional therapy, anthroposophic treatment was associated with much lower use of antibiotics and antipyretics as well as quicker recovery, fewer adverse reactions, and greater therapy satisfaction. These differences remained after adjustment for country, age, gender, and four markers of baseline severity. Only 3% of the anthroposophic patients would have agreed to randomization.40

A complex project on anthroposophic healthcare in advanced cancer funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation demonstrated the difficulties of recruiting patients for randomized system comparison even in a university hospital patient population. Although anthroposophic medicine was well integrated into the University Hospital setting and patient compliance with anthroposophic therapy was good, the randomized controlled trial component of the project ultimately had to be abandoned. Still, in the observational part of the study, anthroposophic treatment showed an improvement in physical, psychic, cognitive-spiritual, and social dimensions of quality of life and was perceived by patients as having beneficial effects on physical recovery and well-being, emotional and cognitive-spiritual quality of life, and the quality of human relations and care, while conventional therapy was perceived as beneficial mainly through effects on tumors with alleviation of symptoms and pain.86–89

A system comparison of anthroposophic and conventional healthcare in cancer patients was performed at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. Randomization could not be financed with public funds; therefore, a prospective matched-pair design was implemented. Prior to treatment, quality of life was more compromised in the anthroposophic patients. During and after the anthroposophic treatment, the quality of life improved, whereas the control group treated with conventional medicine showed no change.90,91

Another observational study investigated patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic conditions receiving anthroposophic healthcare over a 12-month period. They achieved a relevant reduction in the local and systemic inflammatory activity, relief of disease symptoms, and an improvement in functional capacity including the psychosocial dimension. Patient satisfaction was high and conventional therapy could largely be avoided or reduced.92 This study gave rise to a large comparative effectiveness study, comparing anthroposophic with conventional healthcare for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; it has concluded but has not yet been published.

Another study investigated chronic facial pain (mostly trigeminal neuralgia, present for more than 10 years in half of patients) that had been conventionally treated to no avail. Anthroposophic treatment was followed by clinical improvement (one-fifth of patients became pain-free and almost two-thirds experienced a clear improvement), and conventional therapeutic agents were reduced.93 A retrospective study showed a favorable cure rate of anorexia nervosa following inpatient anthroposophic therapy.94

Clinical Studies on Single or a Fixed Set of Interventions.

A variety of studies has investigated monotherapies or fixed combination therapies, for instance mistletoe treatment in cancer (see above) and in hepatitis,95–97 betulin-based oleogel in actinic keratosis,98,99 rhythmic embrocation (with Solum oil) in chronic pain,100 hepar magnesium in seasonal fatigue symptoms,101 arnica/echinacea in care of umbilical cords of newborns,102,103 eurythmy therapy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder104, body-temperature enemas in febrile children,105 mistletoe combined with Articulatio coxae or genus D30 in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee,106 Gelsemium comp. in acute occipital muscular pain,107 and many others. Most studies, except one on migraine,108 one on postoperative wound care,109 and one on actinic keratosis,99 showed positive results. Four recent new randomized controlled trials—on Disci/Rhus toxicodendron comp. in chronic low back pain,110 on Articulatio genus D5 in ostheoarthritis of the knee,111 on calendula cream in skin care during radiation,112 and on Ovaria comp. in menopausal symptoms113—found no benefit compared to placebo treatment.

Patient's Perspective.

Patient satisfaction was generally high, and therapeutic expectations were fulfilled.13,42,114 For instance, in a recently completed Dutch survey (Consumer Quality Index, a national standard to measure healthcare quality from the perspective of healthcare users), 2.099 patients reported very high satisfaction with anthroposophic primary care practices (8.4 and 8.3 on a scale of 0 to 10, 10 being the best possible score).115

Safety

A variety of investigations specifically assessed the safety of anthroposophic treatments.13,69,72–74,116–119 In general, the tolerability is good. Adverse reactions are infrequent and mostly mild to moderate in severity. Three types of adverse reactions to anthroposophic medications are commonly described: local reactions from topical application, systemic hypersensitivity including very rare cases of anaphylactic reactions, and aggravation of preexisting symptoms in sensitive patients. In a detailed safety analysis from the AMOS study, the incidence of confirmed adverse reactions to anthroposophic medications was 3% of users and 2% of the medications used116; adverse reactions in eurythmy therapy, art therapy, and rhythmical massage were reported in 3%, 1%, and 5% of the patients, respectively72–74; and no serious adverse reactions were found.116 Theoretically, avoidance of necessary conventional treatment in anthroposophic healthcare settings might pose a risk, but no evidence has been found for this.13,42 Comparative studies found similar81 or lower40,114,120 rates of side effects in anthroposophic than in conventional healthcare.

Cost

Several economic analyses assessed costs of anthroposophic medicine. They point to a favorable cost structure and found cost savings partly due to lower drug costs, fewer specialist referrals, and fewer hospital days and admissions. This cannot be explained by a reduced disease burden—on the contrary, in most studies, anthroposophically treated patients are more severely affected or have been ill for a longer period before starting therapy.13,121–125

Case Reports

Case report methodology has been developed to provide validated and transparent information from the point of care with special focus on individualized healthcare.126–130 Case reports describe the specific anthroposophic treatment approach in detail (eg, see references 27, 67, 68, 131, and 132). Methods for systematic and critical appraisal still have to be worked out.

CONCLUSION

Anthroposophic medicine is an example of a multimodal treatment system—based on a holistic paradigm of the organism, disease, and treatment—that can be fully integrated with conventional medicine in medical practices and hospitals. Great emphasis is put on individualized healthcare. Assessing this healthcare system, an integrative evaluation strategy has been applied, including system approaches as well as studies in isolated treatment components with regard to efficacy, effectiveness, safety, and costs, as well as qualitative methods and high-quality case reports on individual treatment.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest and had no conflicts related to this work to disclose.

Contributor Information

Gunver S. Kienle, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany.; European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products (ESCAMP), Freiburg, Germany.

Hans-Ulrich Albonico, Clinic for Family and Complementary Medicine, Langnau im Emmental, Switzerland..

Erik Baars, European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products (ESCAMP), Freiburg, Germany.; University of Applied Sciences Leiden, The Netherlands; Louis Bolk Institute, Driebergen, The Netherlands.

Harald J. Hamre, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany, Norway.; European Scientific Cooperative on Anthroposophic Medicinal Products (ESCAMP), Freiburg, Germany.

Peter Zimmermann, Department of Gynecology, Plusterveys, Nastola Medical Center, Finland..

Helmut Kiene, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany..

REFERENCES

- 1.Kienle G: Anthroposophische Medizin. Seidler E, editor Wörterbuch medizinischer Grundbegriffe Freiburg, Basel, Wien, Germany: Herder Verlag; 1979: 33–9 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindenberg C. Rudolf Steiner—a biography Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner R. Goethe's theory of knowledge: an outline of the epistemology of his worldview (1886) Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steiner R. Goethe's conception of the world (1897) London: The Anthroposophical Publishing Company; 1928 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner R. The story of my life London: The Anthroposophical Publishing Company; 1928 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiner R. An outline of esoteric science (1910) Great Barrington, MA: Anthroposophic Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner R. The riddles of philosophy (1900/1901) Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner R. Truth and knowledge (1892) Great Barrington, MA: Steiner Books; 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kant I. Critique of pure reason (1781) Mineola, NY: Dover Publications; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.du Bois-Reymond E. Jugendbriefe an Eduard Hallmann Berlin: Reimer Verlag; 1918 [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Helmholtz H. Über die Erhaltung der Kraft Leipzig, Germany: Engelmann Ver-lag; 1915 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virchow R. Über das Bedürfnis und die Richtigkeit einer Medizin vom mechanischen Standpunkt. Arch Path Anat. 1907;7:188 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kienle GS, Kiene H, Albonico HU. Anthroposophic medicine: effectiveness, utility, costs, safety Stuttgart, NY: Schattauer Verlag; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel L. Der dreigliedrige Mensch Dornach: Verlag am Goetheanum; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner R. Wesensglieder und Dreigliederung. In:Anthroposophische Leitsätze (32-34). Dornach 1925. Der Merkurstab. 2007;(4):381 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kienle GS, Kiene H. “Beyond reductionism”—zur Notwendigkeit komplexer, organ-ismischer Ansätze in der Tumorimmunologie und Onkologie; Kienle GS, Kiene H, Die Mistel in der Onkologie. Stuttgart, NY: Schattauer Verlag; 2003: 333–432 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kienle G, Kiene H. From reductionism to holism: systems-oriented approaches in cancer research. Global Adv Health Med. 2012;1(5):68–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosslenbroich B. Outline of a concept for organismic systems biology. Sem Cancer Biol. 2011;21(3):156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner R. Philosophy and anthroposophy (1904-1918) Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, LLC; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner R. Monism and the philosophy of spiritual activity Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner R. The philosophy of freedom: the basis for a modern world conception (1894) Forrest Row, UK: Rudolf Steiner Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner R. Der Kernpunkte der Sozialen Frage in den Lebensnotwendigkeiten der Gegenwart und Zukunft (1919). Dornach, Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner R. Aufsätze über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus und zur Zeitlage 1915-1921 Dornach, Switzerland: Rudolf Steiner Verlag; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abouleish I. Sekem: A sustainable community in the Egyptian Desert Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiner R. Spiritual science and medicine (1920) Forrest Row, UK: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner R, Wegman I. Fundamentals of therapy (1925) Forrest Row, UK: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwab JH, Murphy JB, Andersson P, et al. Eurythmy therapy in anxiety—a case report. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17(4):58–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heusser PH. Akademische Forschung in der Anthroposophischen Medizin Beispiel Hygiogenese: Natur- und geisteswissenschaftliche Zugänge zur Selbstheilungskraft des Menschen. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonovsky A. Salutogenese Tübingen, Germany: Dgvt Verlag; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutenbrunner C, Hildebrandt G, Moog R, et al. Chronobiology and Chronomedicine: Basic Research and Applications. Proceedings of the 7th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Chronobiology, Marburg 1991 Frankfurt am Main, Berlin: Peter Lang; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girke M. Innere Medizin Grundlagen und therapeutische Konzepte der Anthroposophischen Medizin. Berlin: Salumed-Verlag GmbH; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soldner G, Stellmann HM. Individuelle Pädiatrie: Leibliche, seelische und geistige Aspekte in Diagnostik und Beratung Anthroposophisch-homöopathische Therapie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine Integrative medicine and the health of the public: a summary of the February 2009 summit Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burkhardt R, Kienle G: Die Zulassung von Arneimitteln und der Widerruf von Zulassungen nach dem Arzneimittelgesetz von 1976; Stuttgart: Verlag Urachhaus; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauschka M. Zur künstlerischen Therapie Bd.II. Wesen und Aufgabe der Maltherapie Nürnberg, Germany: Karl Ulrich & Co; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mees-Christeller E. Künstlerische Therapie ausgewählter Krankheitsbilder. Merkurstab. 1995;3:261–269 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steiner R. Curative eurythmy (1921). Bristol, UK: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirchner-Bockholt M. Fundamental principles of curative eurythmy London: Temple Lodge Press; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie J, Wilkinson J, Gantley M, et al. A model of integrated primary care: anthroposophic medicine January 2011: the seven-practice study. http://www.ivaa.info/anthroposophic-medicine/research-in-am/the-seven-practice-study/ Accessed October 15, 2013

- 40.Hamre HJ, Fischer M, Heger M, et al. Anthroposophic vs conventional therapy of acute respiratory and ear infections: a prospective outcomes study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(7-8):258–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziegler R. Mistletoe preparation Iscador: are there methodological concerns with respect to controlled clinical trials? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009March;6(1):19–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kienle GS, Glockmann A, Grugel R, et al. Klinische Forschung zur Anthroposophischen Medizin—Update eines Health Technology Assessment-Berichts und Status Quo. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18:269–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hekal IA, Samer T, Ibrahim EI. Viscum Fraxini 2, as an adjuvant therapy after resection of superficial bladder cancer: prospective clinical randomized study. Presented at the43rd Annual Congress of The Egyptian Urological Association in conjunction with The European Association of Urology November 10-14, 2008, Hurghada, Egypt Abstract P8. 120 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molassiotis A, Fernandez-Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alterna-tive medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):655–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fasching PA, Thiel F, Nicolaisen-Murmann K, et al. Association of complementary methods with quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with gynecologic and breast malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2007;55(11):1277–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kienle GS, Kiene H. Die Mistel in der Onkologie: Fakten und konzeptionelle Grundlagen Stuttgart, NY: Schattauer Verlag; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Büssing A, editor Mistletoe: the genus Viscum Amsterdam: Hardwood Academic Publishers; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orhan DD, Kupeli E, Yesilada E, et al. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity of flavonoids isolated from Viscum album ssp. album. Z Naturforsch C. 2006;61(1-2):26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkler K, Leneweit G, Schubert R. Characterization of membrane vesicles in plant extracts. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2005;45(2):57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jager S, Winkler K, Pfuller U, et al. Solubility studies of oleanolic acid and betulinic acid in aqueous solutions and plant extracts of Viscum album L. Planta Med. 2007;73(2):157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eggenschwiler J, von BL, Stritt B, et al. Mistletoe lectin is not the only cytotoxic component in fermented preparations of Viscum album from white fir (Abies pectina-ta). BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007May10;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Büssing A, Schietzel M. Apoptosis-inducing properties of Viscum album L. extracts from different host trees, correlate with their content of toxic mistletoe lectins. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(1A):23–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsässer-Beile U, Lusebrink S, Grussenmeyer U, et al. Comparison of the effects of various clinically applied mistletoe preparations on peripheral blood leukocytes. Arzneim Forsch/Drug Res. 1998;48(II)(12):1185–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valentiner U, Pfüller U, Baum C, et al. The cytotoxic effect of mistletoe lectins I, II and III on sensitive and multidrug resistant human colon cancer cell lines in vitro. Toxicology. 2002;171(2-3):187–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siegle I, Fritz P, McClellan M, et al. Combined cytotoxic action of Viscum album agglutinin-1 and anticancer agents against human A549 lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(4A):2687–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bantel H, Engels IH, Voelter W, et al. Mistletoe lectin activates caspase-8/FLICE independently of death receptor signaling and enhances anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2083–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mueller EA, Anderer FA. Synergistic action of a plant rhamnogalacturonan enhancing antitumor cytotoxicity of human natural killer and lymphokine-activated killer cells: Chemical specificity of target cell recognition. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3646–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu HG, Zollner TM, Klein-Franke A, et al. Enhancement of MHC-unrestricted cyto-toxic activity of human CD56+CD3-natural killer (NK) cells and CD+T cells by rhamnogalacturonan: target cell specificity and activity against NK-insensitive targets. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1994;(120):383–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kienle GS, Kiene H. Influence of Viscum album L (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9(2):142–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kienle GS, Berrino F, Büssing A, et al. Mistletoe in cancer—a systematic review on controlled clinical trials. Eur J Med Res. 2003;8(3):109–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kienle GS, Kiene H. Complementary cancer therapy: a systematic review of prospective clinical trials on anthroposophic mistletoe extracts. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12(3):103–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tröger W, Galun D, Reif M, Schumann A, Stankovic N, Milicevic M. Viscum album [L.] extract therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a randomised clinical trial on overall survival. Eur J Cancer. 2013; In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Kienle GS, Glockmann A, Schink M, et al. Viscum album L. extracts in breast and gynaecologic cancers: a systematic review of clinical and preclinical research. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009June11;28:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mabed M, El-Helw L, Sharma S. Phase II study of viscum fraxini-2 in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(1):65–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matthes H, Buchwald D, Schad F, et al. Treatment of inoperable pancreatic carcinoma with combined intratumoral mistletoe therapy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 2):43315685554 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orange M, Fonseca M, Lace A, et al. Durable tumour responses following primary high dose induction with mistletoe extracts: two case reports. Eur J Integr Med. 2010;2(2):63–9 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Orange M, Lace A, Fonseca M, et al. Durable regression of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma following fever-inducing mistletoe treatment—two case reports. Global Adv Health Med. 2012;1(1):16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Werthmann P, Sträter G, Friesland H, et al. Durable response of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma following high-dose perilesional injections of Viscum album extracts—a case report. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(3-4):324–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kienle GS, Grugel R, Kiene H. Safety of higher dosages of Viscum album L. in ani-mals and humans - systematic review of immune changes and safety parameters. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamre HJ, Becker-Witt C, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Anthroposophic therapies in chronic disease: the Anthroposophic Medicine Outcome Study (AMOS). Eur J Med Res. 2004;9(7):351–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for children with chronic disease: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. BMC Pediatr 2009June19;9:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Eurythmy therapy in chronic disease: a four-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2007April23;7:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Anthroposophic art therapy in chronic disease: a four-year prospective cohort study. Explore NY. 2007;3(4):365–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Rhythmical massage therapy in chronic disease: a 4-year prospective cohort study. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(6):635–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Anthroposophic medical therapy in chronic disease: a four-year prospective cohort study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2007April23;7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, et al. Outcome of anthroposophic medication therapy in chronic disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009February6;2:25–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity: a two-year prospective study in outpatients. Int J Gen Med. 2010August30;3:239–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for anxiety disorders: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. Clin Med Insights: Psychiatry. 2009;2:17–31 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for asthma: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. J Asthma Allergy. 2009November24;2:111–28 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Anthroposophic therapy for chronic depression: a four-year prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2006December15;6:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, et al. Anthroposophic vs conventional therapy for chronic low back pain: a prospective comparative study. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12(7):302–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Long-term outcomes of anthroposophic therapy for chronic low back pain: A two-year follow-up analysis. J Pain Res. 2009June25;2:75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for migraine: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. Open Neurol J. 2010;4:100–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamre HJ, Glockmann A, Tröger W, Kienle GS, Kiene H. Assessing the order of magnitude of outcomes in single-arm cohorts through systematic comparison with corresponding cohorts: an example from the AMOS study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamre HJ, Glockmann A, Kienle GS, Kiene H. Combined bias suppression in single-arm therapy studies. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(5):923–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heusser P, Braun SB, Ziegler R, et al. Palliative inpatient cancer treatment in an anthroposophic hospital: I. Treatment patterns and compliance with anthroposophic medicine. Forsch Komplementmed. 2006;13(2):94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heusser P, Berger Braun S, Bertschy M, et al. Palliative inpatient cancer treatment in an anthroposophic hospital: II. Quality of life during and after stationary treatment, and subjective treatment benefits. Forsch Komplementmed 2006;13(3):156–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.von Rohr E, Pampallona S, van Wegberg B, et al. Experiences in the realisation of a research project on anthroposophical medicine in patients with advanced cancer. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000;130(34):1173–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.von Rohr E, Pampallona S, van Wegberg B, et al. Attitudes and beliefs towards disease and treatment in patients with advanced cancer using anthroposophical medicine. Onkologie 2000;23:558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carlsson M, Arman M, Backman M, Flatters U, Hatschek T, Hamrin E. Evaluation of quality of life/life satisfaction in women with breast cancer in complementary and conventional care. Acta Oncol. 2004;43(1):27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carlsson M, Arman M, Backman M, Flatters U, Hatschek T, Hamrin E. A five-year follow-up of quality of life in women with breast cancer in anthroposophic and conventional care. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2006;3(4):523–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simon L. Ein anthroposophisches Therapiekonzept für entzündlich-rheumatische Erkrankungen. Ergebnisse einer zweijährigen Pilotstudie. Forsch Komplementmed. 1997;4:17–27 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Astrup C, Astrup Sv, Astrup S, et al. Die Behandlung von Gesichtsschmerzen mit homöopathischen Heilmitteln. Erfahrungsheilkunde. 1976;3:89–96 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schäfer PM: Katamnestische Untersuchung zur Anorexia nervosa In: Bissegger M, editor Die Behandlung von Magersucht: ein integrativer Therapieansatz. Stuttgart: Verlag Freies Geistesleben; 1998:130–60 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huber R, Lüdtke R, Klassen M, et al. Effects of a mistletoe preparation with defined lectin content on chronic hepatitis C: an individually controlled cohort study. Eur J Med Res. 2001;6(9):399–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tusenius KJ, Spoek JM, Kramers CW. Iscador Qu for chronic hepatitis C: an exploratory study. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9(1):12–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tusenius KJ, Spoek AM, van HJ. Exploratory study on the effects of treatment with two mistletoe preparations on chronic hepatitis C. Arzneimittelforschung. 2005;55(12):749–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huyke C, Laszczyk K, Scheffler A, et al. Behandlung aktinischer Keratose mit Birkenkorkenextrakt: Eine Pilotstudie. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4(2):132–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huyke C, Reuter J, Rodig M, et al. Treatment of actinic keratoses with a novel betulin-based oleogel. A prospective, randomized, comparative pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Ostermann T, Blaser G, Bertram M, Michalsen A, Matthiessen PF, Kraft K. Effects of rhythmic embrocation therapy with solum oil in chronic pain patients: a prospective observational study. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):237–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Baars EW, Gans S, Ellis EL. The effect of hepar magnesium on seasonal fatigue symptoms: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(4):395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guala A, Pastore G, Garipoli V, Agosti M, Vitali M, Bona G. The time of umbilical cord separation in healthy full-term newborns: a controlled clinical trial of different cord practices. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(5):350–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Janke S, Seidler A, Schmidt E. Schnellere Nabelheilung durch WecesinÒ Streupuder. Die Hebamme. 1997;10:115–7 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Majorek M, Tüchelmann T, Heusser P. Therapeutic eurythmy—movement therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a pilot study. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2004February;10(1):46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ulbricht M. Antipyretische Wirkung eines körperwarmen Einlaufes. Inaugural-Dissertation. Tübingen; 1991

- 106.Gärtner C. Therapie der Arthrosen grosser Gelenke. Merkurstab. 1999;1:48–51 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gärtner C. Der akute muskuläre Okzipitalschmerz. Therapiestudie mit lokalen Infil-trationen Gelsemium compositum. Merkurstab. 1999;4:244–9 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Krabbe AA, Olesen J. Ferrumkvarts som profylaktikum ved migræne. En dobbelt-blind undersøgelse. Ugeskr Laeger. 1980;142(8):516–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jeffrey SLA, Belcher JC. Use of Arnica to relieve pain after carpal-tunnel release surgery. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8(2):66–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pach D, Brinkhaus B, Roll S, et al. Efficacy of injections with Disci/Rhus Toxicodendron Compositum for chronic low back pain—a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e26166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Huber R, Prestel U, Bloss I, Meyer U, Lüdtke R. Effectiveness of subcutaneous in-jections of a cartilage preparation in osteoarthritis of the knee—a randomized, placebo controlled phase II study. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(3):113–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sharp L, Finnilä K, Johansson H, Abrahamsson M, Hatschek T, Bergenmar M. No differences between Calendula cream and aqueous cream in the prevention of acute radiation skin reactions—results from a randomised blinded trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013August;17(4):429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.von Hagens C, Schiller P, Godbillon B, et al. Treating menopausal symptoms with a complex remedy or placebo: a randomized controlled trial. Climacteric 2012;15(4):358–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Esch BM, Marian F, Busato A, Huesser P. Patient satisfaction with primary care: an observational study comparing anthroposophic and conventional care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Koster EB, Ong RRS, Heybroek-Bellwinkel R, et al. CQ-Index Antroposofische Gezondheidszorg Constructie en validering. Leiden: Lectoraat Antroposofische Gezondheidszorg; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Tröger W, Willich SN, Kiene H. Use and safety of anthroposophic medications in chronic disease: a 2-year prospective analysis. Drug Saf. 2006;29(12):1173–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Baars EW, Adriaansen-Tennekes R, Eikmans KJ. Safety of homeopathic injectables for subcutaneous administration: a documentation of the experience of prescribing practitioners. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(4):609–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hamre HJ, Glockmann A, Fischer M, et al. Use and safety of anthroposophic medications for acute respiratory and ear infections: a prospective cohort study. Drug Target Insights. 2007;2:209–19 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jeschke E, Ostermann T, Luke C, et al. Remedies containing Asteraceae extracts: a prospective observational study of prescribing patterns and adverse drug reactions in German primary care. Drug Saf. 2009;32(8):691–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Plangger N, Rist L, Zimmermann R, von Mandach U. Intravenous tocolysis with Bryophyllum pinnatum is better tolerated than beta-agonist application. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;124(2):168–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, et al. Health costs in patients treated for depression, in patients with depressive symptoms treated for another chronic disorder, and in non-depressed patients: a two-year prospective cohort study in anthroposophic outpatient settings. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11(1):77–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, Ziegler R, Willich SN, Kiene H. Health costs in anthroposophic therapy users: a two-year prospective cohort study. BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Studer HP, Busato A. Comparison of Swiss basic health insurance costs of complementary and conventional medicine. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(6):315–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Studer HP, Busato A. Development of costs for complementary medicine after provisional inclusion into the Swiss basic health insurance. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(1):15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kooreman P, Baars EW. Patients whose GP knows complementary medicine tend to have lower costs and live longer. Eur J Health Econ. 2012December;13(6):769–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kienle GS. Why medical case reports? Global Adv Health Med. 2012;1(1):8–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kienle GS, Kiene H. Clinical judgement and the medical profession. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):621–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kiene H, Schön-Angerer T. Single-case causality assessment as a basis for clinical judgment. Altern Ther Health Med. 1998;4(1):41–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kiene H. Komplementäre Methodenlehre der klinischen Forschung Cognition-based Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kiene H, Hamre HJ, Kienle GS. In support of clinical case reports: a system of causality assessment. Global Adv Health Med. 2013;2(2):28–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wode K, Schneider T, Lundberg I, Kienle GS. Mistletoe treatment in cancer-related fatigue: a case report. Cases J. 2009January22;2(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kienle GS, Meusers M, Quecke B, Hilgard D. Patient-centered diabetes care in children: an integrated, individualized, systems-oriented, and Multidisciplinary Approach. Global Adv Health Med 2013;2(2):12–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]