Abstract

During the 2009 A(H1N1) influenza pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) asked all Member States to provide case-based data on at least the first 100 laboratory-confirmed influenza cases to generate an early understanding of the pandemic and provide appropriate guidance to affected countries. In reviewing the pandemic surveillance strategy, we evaluated the utility of case-based data collection and the challenges in interpreting these data at the global level. To do this, we assessed compliance with the surveillance recommendation and data completeness of submitted case records and described the epidemiological characteristics of up to the first 110 reported cases from each country, aggregated into regions. From April 2009 to August 2011, WHO received over 18 000 case records from 84 countries. Data reached WHO at different time intervals, in different formats and without information on collection methods. Just over half of the 18 000 records gave the date of symptom onset, which made it difficult to assess whether the cases were among the earliest to be confirmed. Descriptive epidemiological analyses were limited to summarizing age, sex and hospitalization ratios. Centralized analysis of case-based data had little value in describing key features of the pandemic. Results were difficult to interpret and would have been misleading if viewed in isolation. A better approach would be to identify critical questions, standardize data elements and methods of investigation, and create efficient channels for communication between countries and the international public health community. Regular exchange of routine surveillance data will help to consolidate these essential channels of communication.

Résumé

Pendant la pandémie de grippe à virus A(H1N1) de l'année 2009, l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS) a demandé à tous les États membres de fournir les données par cas sur au moins les 100 premiers cas de grippe confirmés en laboratoire afin d'obtenir une compréhension précoce de la pandémie et de fournir les directives appropriées aux pays touchés. En examinant la stratégie de surveillance de la pandémie, nous avons évalué l'utilité de la collecte des données par cas et les défis à relever dans l'interprétation de ces données au niveau mondial. Pour ce faire, nous avons évalué le respect des recommandations en matière de surveillance et l'exhaustivité des données des dossiers des cas soumis, et nous avons décrit les caractéristiques épidémiologiques des 110 premiers cas signalés de chaque pays, regroupés en régions. Sur la période allant d'avril 2009 à août 2011, l'OMS a reçu plus de 18 000 dossiers de cas fournis par 84 pays. Les données sont parvenues à l'OMS à différents intervalles de temps, sous différents formats et sans informations sur les méthodes de collecte. À peine plus de la moitié des 18 000 dossiers a donné la date d'apparition des symptômes, ce qui ne permet pas d'évaluer si les cas reçus faisaient partie des premiers cas à être confirmés. Les analyses épidémiologiques descriptives se sont limitées à synthétiser les rapports d'âge, de masculinité et d'hospitalisation. L'analyse centralisée des données par cas n'a que très peu de valeur dans la description des principales caractéristiques de la pandémie. Les résultats sont difficiles à interpréter et pourraient induire en erreur s'ils sont pris isolément. Une meilleure approche consisterait à identifier les questions essentielles, à normaliser les éléments des données et les méthodes d'investigation, et à créer des canaux efficaces de communication entre les pays et la communauté de la santé publique internationale. Les échanges réguliers de données de surveillance de routine aideront à consolider ces canaux de communication essentiels.

Resumen

Durante la pandemia de gripe A (H1N1) del año 2009, la Organización Mundial de la salud (OMS) pidió a todos los Estados miembros que proporcionaran datos de hasta los primeros 100 casos de gripe confirmados en laboratorios con objeto de comprender con rapidez la pandemia y proporcionar orientación adecuada a los países afectados. Con objeto de examinar la estrategia de vigilancia de la pandemia, hemos evaluado la utilidad de la recogida de datos sobre casos y los desafíos que supuso la interpretación de esos datos a nivel internacional. Para ello, evaluamos el cumplimiento con las recomendaciones de vigilancia y la integridad de los datos de los registros enviados y describimos las características epidemiológicas de, como mucho, los 110 primeros casos de cada país, agrupados por regiones. Entre abril de 2009 y agosto de 2011, la OMS recibió más de 18 000 registros de casos de 84 países en intervalos de tiempo y formatos distintos, y sin información alguna sobre los métodos de recogida. Solo algo más de la mitad de los 18 000 registros indicaba la fecha de aparición de los síntomas, lo que dificultó evaluar si los casos se encontraban entre los primeros que se confirmaron. Los análisis epidemiológicos descriptivos se limitaron a resumir las proporciones por edad, sexo y hospitalización. Los análisis centralizados de datos sobre casos tuvieron poco valor en la descripción de las características fundamentales de la epidemia. Fue difícil interpretar los resultados, que habrían resultado engañosos si se hubieran observado de forma aislada. Un enfoque más apropiado permitiría identificar las cuestiones críticas, estandarizar los datos y los métodos de investigación, y crear canales de comunicación entre los países y la comunidad sanitaria internacional. El intercambio regular de datos de vigilancia rutinarios ayudará a consolidar dichos canales de comunicación fundamentales.

ملخص

طلبت منظمة الصحة العالمية أثناء جائحة الأنفلونزا A (H1N1) في عام 2009 من جميع الدول الأعضاء تقديم البيانات المستندة إلى الحالات بشأن أول مائة حالة أنفلونزا على الأقل تم التأكد منها مختبرياً لإصدار تفاهم مبكر عن الجائحة وتقديم الإرشاد الملائم للبلدان المتأثرة. ولدى استعراض استراتيجية ترصد الجائحة، قمنا بتقييم فائدة جمع البيانات المستندة إلى الحالات وتحديات تفسير هذه البيانات على الصعيد العالمي. ولإجراء هذا، قمنا بتقييم الامتثال بتوصيات الترصد واكتمال بيانات سجلات الحالة المقدمة ووصف الخصائص الوبائية لأول 110 حالة تم الإبلاغ عنها من كل بلد، مجمعة حسب الأقاليم. وفي الفترة من نيسان/ أبريل 2009 إلى آب/ أغسطس 2011، تلقت منظمة الصحة العالمية ما يزيد عن 18000 سجل حالة من 84 بلداً. ووصلت البيانات منظمة الصحة العالمية على فترات مختلفة، بتنسيقات مختلفة ودون معلومات عن طرق جمع البيانات. وذكر تقريباً ما يزيد عن نصف السجلات البالغ عددها 18000 سجل تاريخ ظهور الأعراض، الأمر الذي أدى إلى صعوبة تقييم ما إذا كانت الحالات بين الحالات الأولى التي تم تأكيدها. واقتصرت التحليلات الوبائية الوصفية على تلخيص العمر والجنس ونسب الإدخال إلى المستشفيات. وكانت قيمة التحليل المركزي للبيانات المستندة إلى الحالات منخفضة في وصف السمات الرئيسية للجائحة. وكان من الصعب تفسير النتائج وكانت ستكون مضللة إذا تم استعراضها بشكل منعزل. وكان النهج الأفضل هو تحديد الأسئلة الحرجة وتوحيد عناصر البيانات وأساليب التحري وإنشاء قنوات فعالة للاتصال بين البلدان ومجتمع الصحة العمومية الدولي. وسوف يساعد تبادل بيانات الترصد الروتينية على نحو منتظم في توطيد قنوات الاتصال الأساسية تلك.

摘要

在2009 年甲型H1N1 流感大流行期间,世界卫生组织(WHO)要求所有成员国提供有关至少前100 例实验室确诊流感基于病例的数据,以形成对流感的早期理解,为受影响的国家提供适当的指导。在回顾流行病监测策略方面,我们对基于病例的数据收集进行了效用评估,并探讨了在全球层面解释这些数据的挑战。为此,我们评估了对监视建议的符合性以及所提交的病例记录数据的完整性,并描述了按地区累计每个国家早期最多达110 个报告病例的流行病学特征。从2009 年4 月到2011 年8 月,世卫组织收到84 个国家超过1.8 万例记录。数据以不同时间间隔、不同的格式上报世卫组织,但没有提供收集方法的信息。在1.8 万例记录中,仅有超过一半的记录给出症状出现的日期,这样就很难评估这些病例是否属于最早确认的病例。描述性流行病学分析仅限于总结年龄、性别和住院比率。对基于病例的数据进行的集中分析在描述流行病关键特性方面几乎没有价值。这些结果很难解释,如果独立看待,会产生误导。更好的方法是识别关键问题,规范数据元素和调查方法,并在各个国家和国际公共卫生社区之间建立高效的沟通渠道。定期交流常规监测数据将有助于巩固这些必要的沟通渠道。

Резюме

Во время пандемии вируса гриппа А (H1N1) в 2009 году Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) обратилась ко всем государствам-членам с просьбой предоставить поименные данные по крайней мере по первым 100 лабораторно подтвержденным случаям заражения гриппом, с целью формирования раннего понимания пандемии и обеспечения соответствующими рекомендациями затронутых пандемией стран. При рассмотрении стратегии эпиднадзора за пандемией оценивалась полезность сбора поименных данных и проблемы интерпретации этих данных на глобальном уровне. Для этого оценивалось выполнение рекомендаций по эпиднадзору и полнота данных в представленных историях болезни, а также описывались эпидемиологические характеристики по первым 110 зарегистрированным случаям из каждой страны, которые были сгруппированны по регионам. С апреля 2009 г. по август 2011 г. ВОЗ получила более 18 000 историй болезни из 84 стран. Данные поступали в ВОЗ с разными временными интервалами в разных форматах и без информации о методах сбора данных. Лишь более чем в половине из 18 000 случаев указывалась дата появления симптомов, что затрудняло определение самых ранних подтвержденных случаев заболевания. Описательные эпидемиологические анализы ограничивались данными по возрасту, полу и коэффициентам госпитализации. Централизованный анализ поименных данных принес мало пользы для описания ключевых особенностей пандемии. Испытывались трудности в интерпретации данных, рассмотрение которых по отдельности могло привести к неверному истолкованию. Лучшим подходом было бы определение важнейших проблем, стандартизация элементов данных и методов исследования, а также создание эффективных каналов взаимодействия между странами и международным сообществом специалистов здравоохранения. Регулярный обмен данными повседневного эпиднадзора будет способствовать консолидации этих важных каналов взаимодействия.

Introduction

Pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 illustrated the importance of several aspects of pandemic preparedness and response. One was the need for timely surveillance data to inform policy decisions about public health response and mitigation activities. Throughout the entire course of the pandemic there was a critical need for data to describe the clinical presentation and course of the illness, estimate the epidemiological parameters related to the spread of the virus and the clinical severity of infection, and assess the impact of the pandemic on health-care systems. The sharing of these data with the international public health community by countries affected in the course of the pandemic made it possible for countries to learn about the behaviour of the virus and for the World Health Organization (WHO) to modify recommendations for surveillance and response.

From 2004 to 2007, WHO coordinated a series of global consultations to design a pandemic surveillance strategy.1–3 These consultations culminated in the publication of the Global surveillance during an influenza pandemic manual on the WHO web site on 28 April 2009.4 A comprehensive early assessment was an important part of the strategy designed to generate a preliminary understanding of the severity of the pandemic, identify the affected populations, and estimate hospitalization rates for the planning of health services. The guidelines described the data elements to be collected and shared with WHO as part of the early assessment. These included individual case reports containing clinical and demographic data on at least 100 of the earliest laboratory-confirmed cases and describing the methods that countries used to collect these data.

With the spread of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, an adapted interim surveillance manual containing a link to the suggested data collection form was published on the WHO web site on 29 April 2009.5 Following the declaration of the pandemic, this guidance was updated on 10 July 2010 with a suggested form for the collection of data on at least the first 100 laboratory-confirmed cases. The form included data variables for: demographics; date of symptom onset and type of symptoms experienced; medical history, including vaccination and pre-exposure antiviral treatment; pneumonia and its complications; treatment, including hospitalization, admission to an intensive care unit and need for mechanical ventilation; and outcome (Fig. 1).6

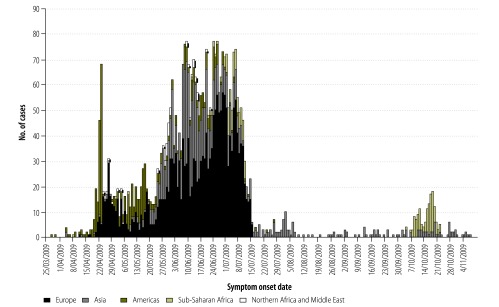

Fig. 1.

Earliera cases of A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic influenza, by region, 25 March to 4 November 2009 (n = 3710)

a Defined as the first 110 cases by date of symptom onset.

In this paper, we examine whether case-based data reporting was useful in meeting the stated objectives of the comprehensive early assessment component of pandemic surveillance guidelines. We do so by evaluating the level of country participation, the resulting data quality and completeness of the data, and the challenges in analysing and interpreting such data at the global level. The results of this evaluation are intended to inform future pandemic surveillance recommendations.

Individual case-based data collection was only one part of the WHO pandemic surveillance strategy, which also included early case detection and investigation and the collection and dissemination of virological surveillance data and of other critical data from a wide variety of sources.7–13 These surveillance components are not evaluated in this paper.

Collecting and collating case-based data

From 29 April 2009 to August 2010, WHO International Health Regulations (IHR) contact points at each of the six WHO regional offices collaborated with the IHR National Focal Points to facilitate collection of paper and/or electronic case-based clinical and epidemiological data from early laboratory-confirmed cases. This information was sent to WHO headquarters in Geneva to produce the global case-based dataset. However, data reached WHO at different time intervals and in different formats. No countries reported exactly the same variables and all reported them in slightly different formats.

Interim analyses of the global dataset were conducted in July 2009, February 2010, August 2010 and August 2011 – upon receipt of final submission of individual country case-based data. This paper assesses the final global dataset as of 31August 2011. We assumed that case records represented only laboratory-confirmed cases, as specified in the surveillance recommendation.

The global case-based dataset

We examined the global case-based dataset from two perspectives. First we assessed the uptake of the recommendation to collect and submit case-based data and the degree of compliance4–6 by evaluating the total number of countries reporting and the total number of case records submitted from different geographic regions. We then examined the value of using a limited number of earlier case reports to identify population groups at risk of infection and severe disease. Since the original intent of the comprehensive assessment segment of pandemic surveillance was to use the first 100 or so cases from each country to characterize the pandemic, we summarized the epidemiological characteristics of up to 110 of the earliest cases, obtained only from case records that included the date of onset of illness. We did this to represent cases collected in conformity with the guidance. For example, if a country submitted 234 records, the first 110 by date of symptom onset were defined as “earlier cases”. Cases for which no date of onset was given were excluded from this evaluation.

The epidemiological characteristics we evaluated included age and sex distribution, hospitalization ratios, complications and illness outcome (Table 1). We also evaluated clinical features, defined by symptom fields (Table 2). These characteristics were assessed by region and globally.

Table 1. Earliera cases of A(H1N1) pandemic influenza, by region, 2009.

| Characteristic | Region |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Americasb | Europec | Asiad | Northern Africa and Middle Easte | Sub-Saharan Africaf | All | |

| No. of countries | 6 | 38 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 81 |

| No. of case records (% of all early cases) | 464 (12) | 1961 (53) | 1026 (28) | 44 (1) | 215 (6) | 3710 |

| No. with age data (% complete) | 464 (100) | 1937 (99) | 1018 (99) | 41 (93) | 212 (99) | 3672 (99) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 17 (11–28) | 24 (17–34) | 23 (14–36) | 27 (21–35) | 18 (8–25) | 23 (14–33) |

| No. with sex data (%) | 460 (99) | 1942 (99) | 1026 (100) | 43 (98) | 215 (100) | 3686 (99) |

| Males (%) | 230 (50) | 1046 (54) | 544 (53) | 19 (44) | 109 (49) | 1945 (53) |

| No. with imported case data (% complete) | 153 (33) | 1901 (97) | 975 (95) | 25 (57) | NA | 3054 (82) |

| No. imported (%) | 75 (50) | 1377 (72) | 502 (51) | 20 (80) | NA | 1974 (65) |

| No. with hospital data (% complete) | 374 (81) | 1548 (79) | 920 (90) | 28 (64) | 110 (51) | 2980 (80) |

| No. hospitalized (%) | 131 (35) | 513 (33) | 667 (73) | 23 (82) | 2 (2) | 1336 (45) |

| No. of hospitalized cases with age data | 131 | 510 | 662 | 23 | 2 | 1328 |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 21 (10–31) | 24 (18–34) | 23 (14–37) | 29 (24–42) | 14 (4–24) | 23 (15–35) |

| No. with fatal outcome data (% complete) | 295 (64) | NA | 43 (4) | 2 (5) | 105 (49) | 445 (12) |

| No. of fatal cases (%) | 2 (0.6) | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available.

a Defined as the first 110 cases by date of symptom onset.

b Bahamas, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Panama and the United States of America.

c Andorra, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

d Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China (with Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [SAR] and Macao SAR), the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, India, Japan, Kiribati, Laos, Malaysia, Micronesia (Federated States of) Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, New Zealand, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Samoa, Singapore, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, Tonga, Vanuatu, Viet Nam.

e Israel, Lebanon, Morocco, Qatar and the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

f Rwanda and South Africa.

Note: Case data missing date of onset were excluded. Therefore, not all countries that contributed data are listed. Geographic grouping was used rather than the official WHO regions as this better reflects the spread of the virus.

Table 2. Number and proportion of earlier cases of A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic influenza in which influenza symptoms were reported, all regions, 2009.

| Symptom | No. (%) of earlier casesa (n = 3710) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Completeb | Symptom | |

| Fever | 2791 (75) | 1905 (68) |

| Cough | 2764 (75) | 1703 (62) |

| Sore throat | 2075 (56) | 1041 (41) |

| Coryza | 2515 (68) | 841 (33) |

| Headache | 2501 (67) | 791 (32) |

| Myalgia | 2462 (66) | 693 (28) |

| Productive cough | 1878 (51) | 374 (20) |

| Shortness of breath | 2489 (67) | 223 (9) |

| Diarrhoea | 2435 (66) | 165 (7) |

a Defined as the first 110 cases by date of symptom onset.

b Indicates that the symptom data field was filled (i.e not blank).

Ethics

This was an observational global surveillance programme in which case data contained no personal identifiers. Countries voluntarily submitted the data to WHO. During development of surveillance guidelines, WHO sought legal and ethical advice on the collection of these data. Prior to submitting this paper for publication, WHO sought and received consent to publish these findings from all countries included in this analysis.

Uptake of recommendation

As of 6 July 2009, a total of 94 512 cases and 429 deaths attributed to pandemic influenza had been reported to WHO by 135 countries and overseas territories.7 By that time, WHO had received individual case data for 2774 of the reported cases from 43 of the 135 countries; 2139 (86%) of the cases were reported by 21 countries.

From April 2009 to August 2011, a total of 18 311 individual case reports of laboratory-confirmed influenza caused by the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus were received at WHO headquarters from 84 of its 193 Member States. The majority were submitted from January to March 2010, but the last case reports arrived in August 2011. The 84 countries represented all continents; however, European countries contributed 9177 (50%) of the case reports contained in the global dataset. One European country alone submitted 6002 case records – 33% of the total case records received. The fewest reports came from northern Africa and the Middle East, which, combined, submitted 47 case records. Information on the methods used to identify and select the cases for data collection was not included in any of the reports.

Inclusion of date of onset

Of the 18 311 case-based records available to WHO, 9932 (54%) included the date of symptom onset and 3710 cases met our definition for “earlier” cases (Table 1). Data from three countries were excluded because date of onset was missing. Date of onset for the earlier cases from 81 countries ranged from 28 March to 8 November 2009. The earliest cases were reported from countries in the Americas and Asia (Fig. 1).

For the epidemiological characteristics that we evaluated, data completeness ranged from 4% for illness outcome to 99% for age and sex (Table 1). Nine of the 17 symptom fields on the WHO case summary form (Appendix A, available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/caseformadapted20090508.pdf) were reported by all regions. Completeness of these symptom fields ranged from 51% (productive cough) to 75% (fever) (Table 2).

Global age and sex distribution

The median age of early cases was relatively consistent regionally and globally. It was 23 years (interquartile range, IQR: 14–33) overall, and slightly lower in the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa (Table 1). There were slightly more males (53%) than females among the earlier cases.

Adequacy of data to assess severity

Of 3710 earlier case records, 2980 (80%) included hospitalization data; of which 1336 cases (45%) had been hospitalized. The Americas and Europe reported lower rates of hospitalization among earlier cases than countries in Asia, Northern Africa and the Middle East (Table 1). Of 28 cases in northern Africa and the Middle East with hospitalization data, 23 (82%) were hospitalized (Table 1). Information on the reason for the hospitalization was seldom provided in the explanatory notes accompanying the data.

Of 3495 earlier case records from the Americas, Asia, Europe, northern Africa and the Middle East, 1764 (50%) included information about pneumonia. Pneumonia had been diagnosed in 69 (4%) of these 1764 cases. Data on mechanical ventilation were complete for only 177 (13%) of the 1336 hospitalized cases, of which 53 (30%) received mechanical ventilation.

Symptoms and clinical outcomes

The most common signs and symptoms recorded in all regions were fever, cough and sore throat (Table 2). However, the regions reported symptoms in different ways, so the denominators for case reports with symptom information were different, which makes comparisons difficult. Only 445 (12%) case records included outcome data. Two deaths were reported among the earlier cases (both in the Americas) and 6 among subsequent cases (all in sub-Saharan Africa) (Table 1).

Discussion

When assessing a new infectious disease outbreak, it is of utmost importance – but enormously difficult – to quickly estimate its key characteristics, such as clinical severity, clinical presentation, the course of the illness and the risk factors associated with infection. All such information is critical for decision-making. Although it is encouraging that 84 of WHO’s 193 Member States shared case-based data, as recommended, reporting was less than timely and declined as the pandemic progressed. Of the 84 affected countries, a little over half had submitted case-based data by early July 2009. However, the conclusions that could be reached from analysis of the data were limited by the absence of information about data collection methods and degree of data completeness. WHO anticipated data reporting to vary somewhat, but substantial differences in data formatting hindered efficient processing. Furthermore, the large proportion of report forms with incomplete data limited the usefulness of the information derived. This was especially true for records that were missing the dates of onset, since the case-based component of the surveillance strategy relied on the assessment of the first few hundred cases.

Although WHO had previously published pandemic preparedness guidance in 1999 and revised it in 2005 and 2009,14–16 specific surveillance guidance for the collection of case-based data on earlier laboratory-confirmed cases was not included until 28 April 2009.5 As a result, countries may not have had enough time to incorporate WHO recommendations into their pandemic surveillance plans. Data collection and compilation in such a large-scale acute event is also challenging in itself. At the national and regional levels, limited laboratory capacity contributed to delays in case confirmation and subsequent reporting. At the global level, challenges included the creation of novel data management systems and data handling processes. This contributed to the delay in analysing and reporting aggregated results.

The key epidemiological characteristics observed in the early stages of the pandemic did not persist throughout, either globally or in the individual regions, nor were observations based on the earlier cases in individual countries the same as those based on the cases reported later. The global case-based data on hospitalization – a key indicator of the clinical severity of infection – illustrated some of the problems involved in interpreting aggregated data. The proportion of cases hospitalized in the Americas and Europe, which were the earliest areas to be affected, was substantially lower than that observed in Asia. Our ability to interpret the data centrally was limited by the lack of a defined system for reporting on (i) patient selection methods; (ii) the case definitions used, (iii) the type of investigation being conducted when a given case was detected; and (iv) the screening and surveillance policies in place at the time of case detection. As a result, we were unable to determine with certainty the reasons for the wide inter-regional disparity in the proportions of hospitalized cases. It is now known, however, that hospitalization policies and testing practices changed over time and varied markedly between regions.17 The threshold for hospitalization and testing was lower at the beginning of the pandemic and many Asian countries adopted a conservative approach to case management by hospitalizing the majority of cases that tested positive, regardless of clinical severity.18,19 Differences in the reported proportion of cases hospitalized over time could have been misinterpreted as an indication of changes in severity without the benefit of other information sources. The patient outcome data needed to generate estimates of deaths from infection with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus proved difficult to obtain in many countries and was therefore not usually submitted to WHO as part of the early case-based data reports.

The overall age and sex distributions and the frequency of the clinical signs observed in the dataset were consistent with later published observations.20,21 However, we observed minor differences in age from region to region. The reasons for this are still unclear. In some countries, surveillance practices that initially targeted returning travellers could have biased the median age of reported cases downward early in the course of the pandemic. Similarly, the investigation of large school outbreaks that occurred, in some cases, as the initial source of community transmission may have led to the identification of predominantly younger cases in later case reports, and national testing policies may have also been a factor. As with hospitalization data, the lack of information about how cases were selected limited our ability to interpret the data.

Despite the fact that our dataset represents the largest number of individual pandemic influenza case reports analysed to date, we were unable to fully evaluate the utility of the surveillance recommendations. We defined the first 110 case reports from each country as “earlier” cases to evaluate the usefulness of this approach in describing key characteristics of a new influenza pandemic. However, we had no information on when data actually became available for analysis, a datum that could have allowed more realistic assessment of the usefulness of case-based data collection. We tried to overcome this limitation by comparing data from different regions. The Americas, for example, were affected earlier than Asia and much of sub-Saharan Africa. Other ways of analysing multinational data may yield more accurate representation of global trends. For example, we presented regionally aggregated data without adjusting for clustering of information within countries. However, even if we had statistically accounted for clustering, differences in transmission, laboratory capacity and reporting patterns between countries and regions would have probably still rendered us unable to draw firm conclusions from the analysis of regionally or globally aggregated data. In the end, the absence of local contextual information is what most hampered our ability to interpret the data. In contrast, the value of a globally aggregated, standardized, minimal case-based dataset has been demonstrated with less rapidly evolving events on a smaller scale, such as the avian influenza H5N1 epidemic.22,23 The global avian influenza case-based dataset has improved our understanding of this disease’s clinical features, risk factors and severity.

Conclusion

The influenza A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic clearly illustrated the challenges of identifying and promoting the appropriate tools for understanding a pandemic early in its course. It also provided an opportunity to evaluate the components of previously published pandemic surveillance strategies. Although the value of a globally aggregated, standardized, minimal case-based dataset has been demonstrated for events on a smaller scale, the value of this type of surveillance is less obvious during a large-scale event. However, health agencies in many countries did conduct case-based surveillance on early cases and, when these data were interpreted in their appropriate context by the countries themselves and the results were shared among WHO Member States through WHO network teleconferences and rapid publication, they provided valuable information that allowed countries subsequently affected to take preparatory steps.24–36

Future guidelines will need to take account of the factors that hinder early reporting. Some might be, for example, pressures on national health systems caused by response activities; differences in health system infrastructure and information systems; reluctance on the part of health authorities to submit incomplete data early in an investigation; and investigators’ eagerness to publish early findings in peer-reviewed publications before their public dissemination. Accordingly, the challenge for WHO is the provision of timely information about acute public health risks of international concern so that countries still unaffected by a pandemic can make informed decisions about prevention and mitigation in the face of constraints to data access.

Improving the comparability and utility of global epidemiological data on influenza requires continued attention to building surveillance and laboratory capacity in all countries. To this end, the WHO Interim Global Epidemiological Surveillance Standards for Influenza (July 2012)37 offers a set of proposed surveillance objectives for a minimal, basic respiratory disease surveillance system. These objectives include the establishment by all countries of minimum standards for case reporting, data collection and analysis as part of inpatient and outpatient respiratory disease surveillance. The Interim Standards include guidance on how to establish sentinel surveillance for influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) and suggest minimum datasets and ways in which countries can share aggregated routine influenza surveillance data with WHO. In the setting of a pandemic or outbreak situation, rates of reporting of influenza-like illness, SARI, pneumonia, hospitalizations and SARI deaths at sentinel sites compared with historical data from sentinel systems would likely give the first indication of the severity of a pandemic as it unfolds. These data are likely to be more reliable than case-based data on early laboratory-confirmed cases, as described in this paper, especially if case-based data were submitted as part of a system established during the pandemic. To further improve the comparability of these data, the Interim Standards include performance indicators for measuring the quality of influenza sentinel surveillance.

Continued development of routine influenza surveillance standards and capacities in all countries is likely to improve the timeliness of data reporting in a future pandemic. Another possible way to improve timeliness is to trial an online system of epidemiological data reporting in which countries can report directly into a database containing virological and demographic data. This might be particularly useful for countries without established influenza surveillance systems for tracking large events, but country pre-approval of the sharing of surveillance data during major events would be required.

The experience gathered during the 2009 pandemic has shown that trying to assemble a global, centralized dataset during a crisis is less effective and efficient than following the approach suggested by the Interim Standards of July 2012: to identify critical questions; standardize data collection methods, critical data elements and methods of investigation; and create efficient channels for the wide dissemination of results, as was done with several WHO networks established during the A(H1N1) pandemic of 2009. Routine exchange of surveillance information will help to establish and consolidate these channels. As recommended by the IHR Review Committee,38 early estimations of severity should remain a key component of pandemic surveillance despite their complexity.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank everyone who contributed to our work and acknowledge the people in the countries that collected the data and forwarded them to WHO headquarters.

The Case-based Surveillance Evaluation Group includes: Sylvain Aldighieri, Maria Almiron, Roberta Andraghetti, Sylvie Briand, Caroline Brown, Amy Cawthorne, Stephanie Davis, Thais DosSantos, Hassan El Bushra, Erika Garcia, Giovanna Jaramillo Gutierrez, Benido Impouma, Marten Kivi, Douglas MacPherson, Mamun Malik, Joshua Mott, Kazu Nakashima, Otavio Oliva, Martin Opoka, Dr Jean-Baptiste Roungou, Johannes Schnitzler, Maria D Van Kerkhove, Kaat Vandemaele, Zhou Weigong, Suzanne Westman, Celia Woodfill.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization [Internet]. WHO consultation on priority public health interventions before and during an influenza pandemic, 16–18 March 2004. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: http://apps.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/consultation/en/index.html [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 2.Report of the WHO consultation on surveillance for pandemic influenza Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO_HSE_GIP_2009.1_eng.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 3.Pandemic influenza preparedness and response: a WHO guidance document. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547680_eng.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013]. [PubMed]

- 4.Global surveillance during an influenza pandemic: version 1 updated draft, April 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/global_pandemic_influenza_surveilance_apr09.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 5.Interim WHO guidance for the surveillance of human infection with swine influenza A(H1N1) virus, 27 April 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/WHO_case_definitions.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 6.Human infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus: updated interim WHO guidance on global surveillance,10 July 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/WHO_case_definition_swine_flu_2009_04_29.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 7.World Health Organization [Internet]. Situation updates – pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/index.html [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 8.Global influenza surveillance network: laboratory surveillance and response to pandemic H1N1 2009. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New influenza A (H1N1) virus: global epidemiological situation, June 2009. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:249–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New influenza A(H1N1) virus infections: global surveillance summary, May 2009. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Considerations for assessing the severity of an influenza pandemic. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epidemiological summary of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus – Ontario, Canada, June 2009. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:485–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Transmission dynamics and impact of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Influenza pandemic plan: the role of WHO and guidelines for national and regional planning Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999 (WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/99.1). Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/whocdscsredc991.pdf [accessed 16 August 2013].

- 15.WHO global influenza preparedness plan: the role of WHO and recommendations for national measures before and during pandemics Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005 (WHO/CDS/CSR/GIP/2005.5). Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/WHO_CDS_CSR_GIP_2005_5.pdf [accessed 16 August 2013].

- 16.Pandemic influenza preparedness and response: a WHO guidance document, 2009 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/pandemic_guidance_04_2009/en/ [accessed 15 August 2013]. [PubMed]

- 17.Garske T, Legrand J, Donnelly CA, Ward H, Cauchemez S, Fraser C, et al. Assessing the severity of the novel influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. BMJ. 2009;339:b2840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao B, Li XW, Mao Y, Wang J, Lu HZ, Chen YS, et al. National Influenza A Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Clinical Investigation Group of China Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2507–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada T, Gu Y, Kamiya H, Komiya N, Odaira F, Sunagawa T, et al. Epidemiology of influenza A(H1N1)v virus infection in Japan, May–June 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19244. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.24.19244-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Harper SA, Shaw M, Uyeki TM, et al. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonsen L. The global impact of influenza on morbidity and mortality. Vaccine. 1999;17(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandun IN, Tresnaningsih E, Purba WH, Lee V, Samaan G, Harun S, et al. Factors associated with case fatality of human H5N1 virus infections in Indonesia: a case series. Lancet. 2008;372:744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bird SM, Farrar J. Minimum dataset needed for confirmed human H5N1 cases. Lancet. 2008;372:696–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infections – Chicago, Illinois, April–July 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:913–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infections – worldwide, May 6, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: swine influenza A (H1N1) infections – California and Texas, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archer B, Cohen C, Naidoo D, Thomas J, Makunga C, Blumberg L, et al. Interim report on pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infections in South Africa, April to October 2009: epidemiology and factors associated with fatal cases. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19369. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.42.19369-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker MG, Wilson N, Huang QS, Paine S, Lopez L, Bandaranayake D, et al. Pandemic influenza A(H1N1)v in New Zealand: the experience from April to August 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19319. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.34.19319-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciblak MA, Albayrak N, Odabas Y, Basak Altas A, Kanturvardar M, Hasoksuz M, et al. Cases of influenza A(H1N1)v reported in Turkey, May–July 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cullen G, Martin J, O’Donnell J, Boland M, Canny M, Keane E, et al. Surveillance of the first 205 confirmed hospitalised cases of pandemic H1N1 influenza in Ireland, 28 April – 3 October 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cutler J, Schleihauf E, Hatchette TF, Billard B, Watson-Creed G, Davidson R, et al. Nova Scotia Human Swine Influenza Investigation Team Investigation of the first cases of human-to-human infection with the new swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in Canada. CMAJ. 2009;181:159–63. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Silva UC, Warachit J, Waicharoen S, Chittaganpitch M. A preliminary analysis of the epidemiology of influenza A(H1N1)v virus infection in Thailand from early outbreak data, June–July 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19292. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.31.19292-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Description of the early stage of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Germany, 27 April–16 June 2009. Novel influenza A(H1N1) investigation team. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19295. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.31.19295-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surveillance Group for New Influenza A Virological surveillance of human cases of influenza A(H1N1)v virus in Italy: preliminary results. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19247. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.24.19247-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health Protection Agency and Health Protection Scotland New Influenza A(H1N1) Investigation Teams Epidemiology of new influenza A(H1N1) in the United Kingdom, April–May 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19213. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.19.19213-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.New influenza A(H1N1) investigation teams. New influenza A(H1N1) virus infections in France, April–May 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19221. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.21.19221-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO Interim Global Epidemological Surveillance Standards for Influenza (July 2012). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/INFSURVMANUAL.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013].

- 38.A64.10. Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005): report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. In: Sixty-fourth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16–24 May 2011 – documents Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_10-en.pdf [accessed 15 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]