Abstract

Objective

This study’s objective was to develop a measure of social health using item response theory as part of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

Methods

After candidate items were generated from review of prior literature, focus groups, expert input, and cognitive interviews, items were administered to youth aged 8–17 as part of the PROMIS pediatric large scale testing. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were used to assess dimensionality and to identify instances of local dependence. Items that met the unidimensionality criteria were subsequently calibrated using Samejima’s Graded Response Model. Differential item functioning was examined by gender and age.

Results

The sample included 3,048 youth who completed the questionnaire (51.8% female, 60% white, and 22.7% with chronic illness). The initial conceptualization of social function and sociability did not yield unidimensional item banks. Rather, factor analysis revealed dimensions contrasting peer relationships and adult relationships. The analysis also identified dimensions formed by responses to positively versus negatively worded items. The resulting 15-item bank measures quality of peer relationships and has strong psychometric characteristics as a full bank or an 8-item short form.

Conclusions

The PROMIS pediatric peer relationships scale demonstrates good psychometric characteristics and addresses an important aspect of child health.

Keywords: item response theory, peer relationships, PROMIS, social health

The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) was developed to advance the science and application of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) in chronic diseases (Ader, 2007). The PROMIS pediatrics projects have focused on the development of self-report PRO item banks across several health domains for youth ages 8–17 (Dewitt et al., 2011; Irwin, Stucky, Langer, et al., 2010; Irwin et al., 2012; Irwin, Stucky, Thissen, et al., 2010; Irwin, Varni, Yeatts, & DeWalt, 2009; Varni et al., 2010; Walsh, Irwin, Meier, Varni, & DeWalt, 2008; Yeatts et al., 2010). This study describes the development of an item bank within the social health domain.

Social health is considered an important aspect of overall quality of life for children and adults (World Health Organization, 1946). Youth who suffer from a range of psychological and behavior challenges, such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, and conduct disorder, often have difficulty managing interpersonal relationships and situations (Dirks, 2007). In addition, pediatric patients with chronic illnesses face unique challenges in their social development and adjustment, especially if they require frequent hospitalizations, intrusive medical procedures, and/or absences from school (Spieth, 1996). As such, PROMIS investigators have included social health as part of an overall domain framework of health (Cella et al., 2007).

In the broadest sense, social health refers to a child’s quality and quantity of social roles and functions with peers, family, and other adults at home, school, and in community activities, as perceived by themselves and others (Denham, Wyatt, Bassett, Echeverria, & Knox, 2009; Dirks, 2007; Rose-Krasnor, 1997; Varni, Burwinkle, Seid, & Skarr, 2003; Wigelsworth, Humphrey, Kalambouka, & Lendrum, 2010). However, this definition is general and difficult to quantify and has led to various representations of social health in the literature. Researchers have used a number of terms to describe social health, such as social functioning, social competence, perceived competence, social adjustment, social support, and belongingness, and there is little consensus about how to define and measure it in children or adults (Dirks, 2007; Rose-Krasnor, 1997). Despite the use of different terms and disagreement about conceptual definitions, there is general consensus that there are a set of behaviors and feelings that enable individuals to successfully engage in interpersonal relationships and navigate social situations (Merrell & Gimpel, 1998).

In the PROMIS domain framework, social health encompasses participation in activities with others, carrying out one’s usual roles and responsibilities, and relationships and connections with important others (PROMIS Cooperative Group, n.d.). These relationships, roles, and responsibilities can include individuals, groups, communities, and society as a whole. The term “social health” refers to a higher order component, with measurable subcomponents, including social function (e.g., performance of one’s usual roles and responsibilities) and social relationships (e.g., understanding and communication; companionship; and the quality, reciprocity, and size of an individual’s social network).

Based on reviews of other proposed models of social health (Denham et al., 2009; Landgraf, Abetz, & Ware, 1996; Ravens-Sieberer & European KIDSCREEN Group, 2006) and comments from focus groups (Walsh et al., 2008), the PROMIS pediatrics team proposed two subdomains for initial item bank development: social function and sociability. Social function is defined as involvement in and satisfaction with an individual’s usual roles in life’s situations and activities (PROMIS Cooperative Group, n.d.). For the pediatric social health framework, social function was categorized into four areas: (a) school, (b) friends/peers, (c) family, and (d) activities. Sociability, defined as the ability to get along and foster relationships with others, was divided into three areas: (a) being a good friend and colleague, (b) getting along with parents, and (c) relationships with teachers. Many items developed to measure social function, such as “I was able to count on my friends” and “I was able to have fun with my friends,” also seemed to be measuring sociability. Based on this overlap between social function and sociability, a secondary aim of this study was to examine whether social function and relationships were distinct domains in this pediatric sample.

During mid to late childhood (6–12 years old), children spend an increasing amount of time interacting with peers as a result of formal schooling and participation in afterschool activities (Parker, Rubin, Erath, Wojslawowicz, & Buskirk, 2006). At this stage, peer interactions in group settings hold strict rules for participation, teaching children how to adjust to social norms (Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999). The nature of friendships allows children the opportunity to establish lasting relationships where they develop the ability to understand and appreciate other points of view and foster their sense of empathy. This, in turn, builds the capacity for intimate relationships later in life. During adolescence (ages 13–18), teenagers have fewer, more selective friends. These relationships have an increased emphasis on intimacy and self-disclosure, through which individuals begin to better understand themselves and other relationships (Parker et al., 2006).

Perceived reciprocity, the extent to which relational bonds are thought to be shared and friendships are reciprocated, is another important aspect of childhood relationship development (Hartup, 1989). Because of the importance of perceived reciprocity, the social health item bank included bidirectional questions such as “I was good at making friends” and “Other kids wanted to be my friend.” These items also provide further examples of ways in which social roles and sociability overlap in children. It is important to note that the social health bank was not designed to measure social support.

Assessment Format

Measures of social health in the pediatric population have typically been presented using one or more of the following formats: (a) proxy reporting by a parent/guardian or teacher, (b) sociometric scales or peer ratings, and (c) child self-reporting (Dirks, 2007; Rose-Krasnor, 1997; Wigelsworth et al., 2010). Proxy reporting is often used when a child, because of cognitive or physical limitations, cannot complete a survey him/herself. Studies examining child and proxy social health measures have found discrepancies between child and proxy responses (Cremeens, Eiser, & Blades, 2006). One reason for this disagreement may be that parents and teachers are not knowledgeable about the dynamics of children’s friendships and personal satisfaction with their peer relationships (Anderson-Butcher, Iachini, & Amorose, 2007). Sociometric scales, which are based on peer rating systems, tend to measure popularity as opposed to a child’s ability to initiate or maintain friendships (Rose-Krasnor, 1997). Certainly, measures of social health that take into account peer and proxy ratings offer a vital perspective (Gerhardt et al., 2012; Mackner, Vannatta, & Crandall, 2012; Noll, Kiska, Reiter-Purtill, Gerhardt, & Vannatta, 2010; Noll, Reiter-Purtill, Vannatta, Gerhardt, & Short, 2007), but self-report ratings are also important because they reflect how individuals feel about their own social health. The aim of this research was to create self-report item banks measuring social roles and sociability in four areas: (a) school, (b) friends/peers, (c) family, and (d) activities.

Item Response Theory

The majority of scales developed to assess social health have used classical test theory (Reise & Waller, 2009). Item response theory (IRT), with its close attention to local dependence and differential item functioning (DIF), can yield a clearer understanding of dimensionality within a measure. The primary objective of this study is to describe the psychometric analyses of the PROMIS pediatric social health item banks and the measurement properties of the resulting PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale, including scale dimensionality, sources of local dependence, and differential item functioning (DIF).

Method

Item Development

PROMIS methodology was used to create potential items for a pediatric social health scale. This methodology has been described in detail elsewhere and is summarized briefly here (DeWalt, Rothrock, Yount, & Stone, 2007). After the subdomains were defined, the next step was to identify and compile social health items from existing scales. Content experts categorized items as measuring social function or sociability. Items were eliminated that were redundant, vague, confusing, or disease specific. New items were written to ensure that there were items that measured a range of functioning across the construct. For example, the research team created items in areas that were not well represented in existing scales, such as social functioning in school and activities as well as with peers and family.

Focus groups provided additional input on domain coverage (Walsh et al., 2008) and individual items, and response options were reviewed in cognitive interviews with children in the target age range (including at least two children under age nine; Irwin et al., 2009). During cognitive interviews, children were asked to complete sets of items and then debrief on what the items meant to them and what information they used to answer the item. Cognitive interviews also covered the response options and time frames of items to ensure they made sense to the children. Items were revised as needed after the cognitive interviews and then underwent further cognitive review. Cognitive interviews were also conducted with items derived from existing scales that passed the selection process. These items were included in the final testing pool only if permission was granted from the developer.

There were initially 74 social health items classified as either social function (53 items) or sociability (21 items). All items included the context statement “In the past 7 days,” a statement in the past tense (e.g., “I was able to have fun with my friends”), and a standard 5-point set of response options: never, almost never, sometimes, often, and almost always.

Sampling Plan

Participants from North Carolina and Texas were recruited in hospital-based outpatient general pediatrics and subspecialty clinics and in public school settings between January 2007 and May, 2008. To be eligible to participate in the large-scale study, subjects were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: be 8 to 17 years; able to speak and read English; and able to see and interact with a computer screen, keyboard, and mouse. Parental informed consent and minor assent were obtained for all children taking the survey. The study received IRB approval from regulatory boards at participating institutions. A more detailed description of the survey methods and the study population has been published previously (Irwin, Stucky, Thissen, et al., 2010).

The 74 social health items (53 social function, 21 sociability) were computer administered on four different test forms along with items from other domains (emotional distress, fatigue, pain, and physical functioning) and a small number of items from legacy scales (Irwin, Stucky, Thissen, et al., 2010). As a result of a study design that included several items from each of the item banks under development, no participant was administered the entire bank of social health items. This sampling plan was intended to avoid undue respondent burden (Irwin, Stucky, Thissen, et al., 2010). Table 1 shows the distribution of the social health items across the four forms; constraints imposed by the numbers of items in other domains led to the concentration of the social health items on forms 3 and 4.

Table 1.

Distribution of Social Health Items Across Four Item Test Forms

| Subdomain | Form 1 | Form 2 | Form 3 | Form 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social function | 6 | 9 | 19 | 19 |

| Sociability | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Other (& Legacy) | 57 | 55 | 43 | 43 |

| Total | 69 | 69 | 67 | 67 |

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. A standardized PROMIS framework was followed for the psychometric item analyses (described in Dewitt et al., 2011; Reeve et al., 2007). After initial verification of data quality, analyses were conducted to ensure that IRT model assumptions were met. Dimensionality of the item pool was examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). All factor analyses used interitem polychoric correlation matrices; EFA used the ULS estimation and oblique CF-Varimax rotation algorithms implemented in the CEFA software (Browne, Cudeck, Tateneni, & Mels, 2004), whereas CFA used either the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) algorithm in the computer program LISREL (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2003) or the weighted least squares with robust standard errors, mean- and variance-adjusted (WLSMV) algorithm (B. Muthén, du Toit, & Spisic, 1997) implemented in the software Mplus (L. Muthén & Muthén, 2004). Investigation of local dependence (LD) included use of the CFA models to identify significant error covariances between pairs or small clusters of items (Hill et al., 2007). If LD was identified, only one of the items was selected from the subset to remain in the item bank and the others were removed.

Items that met the unidimensionality criteria were subsequently calibrated using Samejima’s (1970, 1997) graded response model (GRM) using the Multilog software (du Toit, 2003). For each item, the GRM estimates a slope or discrimination parameter (a), which indicates the degree of association between the item responses and the underlying construct, social health, and four thresholds (bk) for five-category items that reflect the degree of social health at which the most probable response occurs in a given item response category or higher. The fit of the IRT model was evaluated using the SS χ2 statistic (Bjorner et al., 2007; Orlando & Thissen, 2000; Orlando & Thissen, 2003), for which a nonsignificant result is an indicator of adequate model fit; significant values suggest that the underlying table of frequencies should be examined to determine the reason the statistic is large, which may or may not be lack of model fit.

Items were analyzed for differential item functioning (DIF) between males and females, and between younger (8–12) and older (13–17) children, using an IRT-LR DIF detection procedure implemented in the IRTLRDIF software (Thissen, 2001; Thissen, Steinberg, & Wainer, 1993). In this case, DIF would indicate that a factor related to gender or age, but different than social health, affects the item responses; that is a violation of the assumption of unidimensionality. A nonsignificant test statistic indicates an absence of DIF. If statistically significant DIF were detected, the magnitude of the effect size was evaluated graphically using methods outlined by Steinberg and Thissen (2006), and a decision was made to exclude or retain the item.

For both the DIF and item goodness of fit test statistics, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to make inferential decisions in the context of the multiple comparisons (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Williams, Jones, & Tukey, 1999).

A short form was created by selecting items based on the information curves and the item content. Because these items had multiple response choices, the information curves for individual items had substantial overlap. In most cases, the items that were most informative at T = 50 were also most informative at T = 30. As such, the short form was created by selecting items that qualitatively covered the content of the bank and also maximized information for a reliable short form. Although IRT scale scores may be computed for either response patterns or summed scores, summed scores tend to be more widely used for the practical reason that special software is needed to calculate the response pattern scores. When response pattern scores are available, they should be used because they are more precise. The data supplement contains IRT scale scores computed for the short form summed scores (Thissen, Nelson, Rosa, & McLeod, 2001).

Results

The potential social health items were administered to 3,048 children. Each item was administered to at least 754 respondents. The sample was diverse. The group was 51.8% female. The participants reported belonging to the following racial and ethnic groups: 60% white, 21.1% black, 5.6% multiracial, 10.1% other races (Asian, Pacific Islanders, Native American, other), 3.2% race not reported, and 17.5% Hispanic or Latino. Approximately 23% had a chronic medical condition within the past 6 months. The age distribution was split between the younger and older children, with 53% between the ages of 8–12 years old and 47% 13–17 years old (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Participant Characteristics

| Form 1 n = 759 (%) |

Form 2 n = 770 (%) |

Form 3 n = 754 (%) |

Form 4 n = 765 (%) |

Total Forms 1 to 4 n = 3,048 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s gender | |||||

| Male | 382 (50.3) | 351 (45.6) | 355 (47.1) | 382 (49.9) | 1,470 (48.2) |

| Female | 377 (49.7) | 419 (54.4) | 399 (52.9) | 383 (50.1) | 1,578 (51.8) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Child’s age (yrs) | |||||

| 8–12 | 446 (58.8) | 441 (56.4) | 303 (40.2) | 426 (55.7) | 1,616 (53.0) |

| 13–17 | 312 (41.1) | 326 (42.3) | 451 (59.8) | 337 (44.0) | 1,426 (46.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) |

| Child’s race | |||||

| White | 457 (60.2) | 452 (58.7) | 457 (60.6) | 462 (60.4) | 1,828 (60.0) |

| Black or African-American | 154 (20.2) | 168 (21.8) | 172 (22.8) | 150 (19.6) | 644 (21.1) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 (0.6) | 10 (1.3) | 7 (0.9) | 10 (1.3) | 32 (1.0) |

| Asian | 12 (1.6) | 13 (1.7) | 6 (0.8) | 10 (1.3) | 41 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian Other Pacific Is | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) |

| Other | 58 (7.6) | 50 (6.5) | 58 (7.7) | 64 (8.4) | 230 (7.5) |

| Multiple races | 47 (6.2) | 54 (7.0) | 27 (3.6) | 43 (5.6) | 171 (5.6) |

| Missing | 26 (3.4) | 22 (2.9) | 25 (3.3) | 24 (3.1) | 97 (3.2) |

| Child’s ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 614 (80.9) | 641 (83.2) | 617 (81.8) | 619 (80.9) | 2,491 (81.7) |

| Hispanic | 141 (18.6) | 121 (15.7) | 131 (17.4) | 141 (18.4) | 534 (17.5) |

| Missing | 4 (0.5) | 8 (1.1) | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 23 (0.8) |

| Child’s chronic conditions past 6 mo | |||||

| No | 600 (79.0) | 580 (75.3) | 569 (75.5) | 592 (77.4) | 2,341 (76.8) |

| Yes | 157 (20.7) | 187 (24.3) | 180 (23.9) | 169 (22.1) | 693 (22.7) |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | 14 (0.5) |

| Guardian’sa Relationship to Child | |||||

| Parent | 696 (91.7) | 717 (93.1) | 695 (92.2) | 708 (92.6) | 2,816 (92.4) |

| Grandparent | 32 (4.2) | 30 (3.9) | 32 (4.2) | 43 (5.6) | 137 (4.5) |

| Guardian or other | 31 (4.1) | 21 (2.7) | 26 (3.5) | 13 (1.7) | 91 (3.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| Guardian’sa education level | |||||

| ≤8th grade | 12 (1.6) | 16 (2.3) | 13 (1.8) | 16 (2.1) | 57 (1.9) |

| Some high school | 39 (5.1) | 34 (4.4) | 54 (7.2) | 55 (7.2) | 182 (6.0) |

| High school degree/GED | 151 (19.9) | 153 (19.7) | 163 (21.6) | 159 (20.8) | 626 (20.5) |

| Some college/technical degree | 255 (33.6) | 245 (31.8) | 251 (33.2) | 260 (34.0) | 1011 (33.2) |

| College degree | 179 (23.6) | 214 (27.8) | 183 (24.3) | 180 (23.5) | 756 (24.8) |

| Advanced degree | 121 (15.9) | 105 (13.6) | 86 (11.4) | 95 (12.4) | 407 (13.4) |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 0 | 9 (0.3) |

| Data collection site | |||||

| Schools – NC | 57 (7.5) | 57 (7.4) | 49 (6.5) | 51 (6.7) | 214 (7.0) |

| Clinics – NC | 349 (46.0) | 350 (45.5) | 343 (45.5) | 351 (45.9) | 1,393 (45.7) |

| Clinics – TX | 353 (46.5) | 363 (47.1) | 362 (48.0) | 363 (47.4) | 1,441 (47.3) |

Guardian, parent, or caregiver completing sociodemographic form and signing consent documents.

The data from forms 3 and 4 were used for the initial EFAs because those forms included most of the potential social health items. These EFAs revealed two results: (a) The “social function” and “sociability” items did not resolve themselves into factors, or clusters of items representing dimensions of individual differences, and (b) the item sets were factorially complex. Guided by significant changes in the goodness-of-fit statistic and its associated root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the analysts extracted and rotated five factors for the form 3 data and four factors for the form 4 data. Inspection of the items with large loadings on each factor revealed three factors that appeared on both forms. The first of these had large loadings for the positively worded items, the second had large loadings for the negatively worded items, and the third had large loadings for items that asked about relationships with adults (parents, teachers) as opposed to peers. In addition to those three factors common to forms 3 and 4, each form also had factors that involved smaller numbers of items that either reflected closely related content (e.g., “teased other kids” and “was mean to other people”) or wording similarity (e.g., items that included the phrase “got along”).

The analysts abandoned the distinction between “social function” and “sociability” because those did not appear to be dimensions of individual differences supported by the data. Instead, the analysts used the results of the EFAs of the data from forms 3 and 4 to guide the development of CFA models for all four forms. As an illustration of these analyses, Table 3 shows the factor loadings and residual correlations for the four-factor model (with five residual correlations) that was ultimately fitted to the data from form 3. The model shown in Table 3 includes a general factor (which would be the only dimension if the items measured a single construct), and three additional orthogonal factors for the positively worded items, the negatively worded items, and items that involved adults or family. The latter three factors indicate that there are dimensions of individual differences related to endorsement of positively worded items, negatively worded items, and items involving relations with adults. This four-factor model is almost a bifactor model; it would be a bifactor model if each item had nonzero loadings on only one factor in addition to the general factor. That rule is violated by the items on the “Adult” factor and by the residual correlations, so it is an augmented bifactor or two tier model.

Table 3.

Factor Loading Estimates for a CFA Model for the Items on Form 3

| Item stem | Factor loadings

|

Residual correlations

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Positive | Negative | Adult | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| I could talk with my friends. | 0.52 | 0.54 | |||||||

| I felt good about how I got along with classmates. | 0.59 | 0.48 | |||||||

| I felt comfortable with other kids my age. | 0.60 | 0.46 | |||||||

| I felt loved by my parents or guardians. | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.50 | ||||||

| I was good at making friends. | 0.56 | 0.43 | |||||||

| Other kids wanted to be with me. | 0.53 | 0.42 | |0.33| | ||||||

| I did things with other kids my age. | 0.51 | 0.40 | |||||||

| I felt accepted by other kids my age. | 0.56 | 0.41 | |||||||

| My teachers understood me. | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.27 | ||||||

| I wanted to spend time with my family. | −0.03 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||||||

| I was good at talking with adults. | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.12 | |−0.25| | |||||

| I got along better with adults than with other kids my age. | 0.45 | 0.14 | |||||||

| I had problems getting along with my parents or guardians. | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.54 | ||||||

| I got into a yelling fight with other kids. | 0.33 | 0.47 | |||||||

| I had trouble getting along with my family. | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.45 | |0.3| | |||||

| I had trouble getting along with other kids my age. | 0.60 | 0.14 | |||||||

| Other kids made fun of me. | 0.61 | 0.34 | |0.53| | ||||||

| Other kids were mean to me. | 0.72 | 0.21 | |||||||

| I felt different from other kids my age. | 0.65 | 0.30 | |||||||

| I felt bad about how I got along with my friends. | 0.53 | 0.30 | |||||||

| I felt nervous when I was with other kids my age. | 0.61 | 0.20 | |0.27| | ||||||

| I was afraid of other kids my age. | 0.58 | 0.08 | |||||||

| I did not want to be with other kids. | 0.63 | 0.18 | |||||||

| I wished I had more friends. | 0.64 | −0.06 | |||||||

Note. Italicized factor loadings are not significantly different from 0.

The model shown in Table 3 also includes significant residual correlations between five locally dependent pairs of items. Some of these pairs have similar content (“kids wanted to be with me” and “I did things with other kids” or “kids made fun of me” and “kids were mean to me”); others have similar words (“getting along”). This model fit the data for form 3 reasonably well. The goodness of fit χ2 was 338 on 113 df, with associated RMSEA of 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.98. The latter three values are at levels considered to reflect satisfactory fit. Generally, similar models fit the data for the other three forms. The model for form 1 included a general factor and positive and negative second tier factors, and three doublet residual correlations, with a goodness of fit χ2 value of 71 on 32 df, with associated RMSEA of 0.04, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.98 (Table A1 in the online data supplement). The model for form 2 included a general factor and two second-tier factors for items about interactions with peers (that were largely negatively phrased) and with adults (largely positively phrased), and three doublet residual correlations, with a goodness of fit χ2 value of 112 on 42 df, with associated RMSEA of 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.98 (Table A2 in the online data supplement). The model for form 4 was considerably more complex, with a general factor and four second-tier factors for positively and negatively worded items, and for items about interactions with friends and items that reflected meanness or bullying, and three doublet residual correlations, with a goodness of fit χ2 value of 194 on 85 df, with associated RMSEA of 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.99 (Table A3 in the online data supplement).

Using these results as a guide, the pediatric scale development group rethought the measurement goal and concluded that the test item pool would support the development of a scale focused on the quality of peer relationships, using largely positively worded items. Although it appeared there could be another dimension tapping children’s interaction with adults, there were not sufficient items in the pool to make a separate scale for that construct. For the most part, negatively worded items appeared to measure individual differences in the propensity to endorse negative statements; as that propensity was not the target domain, the negatively worded items were removed from the bank.

Based on this redefinition of the measurement goal, 24 items were selected as the potential new item pool. All of the items involve interactions with peers, and almost all are positively worded. Another set of CFA models were fitted to the data for these items (four items on form 1, five on form 2, and eight on form 3, and seven on form 4). Unidimensional CFA models, with error covariances indicating two LD pairs of items on form 3, and one LD pair on form 4, fit the data reasonably well. For form 1, the goodness of fit χ2 value was 7.8 on 2 df, with associated RMSEA of 0.064, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.98; for form 2, χ2 = 7.2 on 5 df, associated RMSEA = 0.025, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99; for form 3, χ2 = 37.1 on 15 df, associated RMSEA = 0.044, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99; and for form 4, χ2 = 76.1 on 10 df, associated RMSEA = 0.098, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97. Before IRT calibration, four additional items were withdrawn because they appeared to be very similar to items that appeared on other forms; given the multiform design, LD could not be detected statistically for items on different forms, so pairs of items that were judged likely to be locally dependent were reduced to a single item.

The remaining 20 items (with the stems listed in Table 4) were calibrated with the graded response model. To avoid potential influence of LD on the item parameter estimates, parameter estimation was calculated twice for the items on forms 3 and 4, once including only one of the items in each pair the CFA had indicated to be locally dependent and a second time including the other item in each pair. The items were checked for DIF between boys and girls; three items exhibited significant gender DIF after the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiplicity. After examining the size of the DIF for each of these items, two were removed from the final item pool [“I could talk with my classmates” (higher scores for boys) and “I was able to stand up for myself with other kids my age” (higher scores for boys)]. For the third item, “Other kids wanted to be my friend,” the DIF was primarily attributable to the fact that the item is slightly more discriminating for girls than for boys; this “nonuniform” DIF was less than one point at any point on the scale. Given this relatively low level of DIF and the usefulness of the item, it was retained. Only one item (“I spent time with my friends”) exhibited significant DIF between younger and older children, and the effect size was very small (i.e., a fraction of a point at all levels of the latent variable) so that item was also retained.

Table 4.

Items in the Peer Relationships Item Bank, With GRM Parameter Estimates and Goodness of Fit Statistics, Along With Items Removed Because of LD or DIF

| Item stem | SFa | a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | SS-χ2 | d.f. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I was able to count on my friends. | x | 2.69 | −1.99 | −1.72 | −0.88 | −0.19 | 24 | 28 | 0.70 |

| I felt accepted by other kids my age. | x | 2.00 | −1.93 | −1.57 | −0.80 | −0.05 | 58 | 29 | <0.01 |

| I was able to talk about everything with my friends. | x | 1.94 | −2.18 | −1.76 | −0.59 | 0.10 | 42 | 29 | 0.06 |

| Other kids wanted to talk to me. | x | 1.90 | −2.96 | −2.25 | −1.00 | −0.06 | 28 | 20 | 0.12 |

| Other kids wanted to be with me. | x | 1.83 | −2.51 | −2.15 | −0.70 | 0.37 | 43 | 28 | 0.03 |

| I was good at making friends. | x | 1.76 | −2.69 | −2.19 | −1.08 | −0.15 | 51 | 28 | 0.01 |

| Other kids wanted to be my friend. | x | 1.54 | −2.65 | −2.11 | −0.78 | 0.44 | 26 | 18 | 0.10 |

| My friends and I helped each other out. | x | 1.74 | −3.01 | −2.53 | −1.36 | −0.48 | 37 | 22 | 0.02 |

| I felt good about my friendships. | 1.76 | −3.04 | −2.61 | −1.56 | −0.58 | 20 | 17 | 0.30 | |

| I was a good friend. | 2.06 | −3.17 | −2.92 | −1.74 | −0.78 | 30 | 17 | 0.03 | |

| I shared with other kids (food, games, pens, etc.). | 1.42 | −2.62 | −2.16 | −0.84 | 0.13 | 33 | 21 | 0.04 | |

| I liked being around other kids my age. | 1.49 | −3.00 | −2.66 | −1.40 | −0.59 | 40 | 29 | 0.09 | |

| I was able to have fun with my friends. | 1.69 | −2.84 | −2.60 | −1.81 | −0.83 | 28 | 16 | 0.03 | |

| I spent time with my friends. | 1.27 | −3.27 | −2.80 | −1.48 | −0.13 | 32 | 29 | 0.31 | |

| I played alone and kept to myself. | 0.65 | −4.94 | −3.47 | −1.38 | 0.22 | 34 | 29 | 0.45 | |

| LD items removed | |||||||||

| I did things with other kids my age. | |||||||||

| I wished I had more friends. | |||||||||

| I was good at talking with other kids my age. | |||||||||

| DIF items removed | |||||||||

| I could talk with my classmates. | |||||||||

| I was able to stand up for myself with other kids my age. | |||||||||

Note. Italicized p values are significant after Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiplicity.

Items marked with “x” in the “SF” column constitute the short form.

The less discriminating items from each of the three LD pairs identified in the CFA analysis were also removed, leaving the 15-item PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships item pool shown in Table 4. The GRM item parameters are shown in Table 4, along with the SS-χ2 item-level diagnostic statistics and their associated d.f. and p values. Two of the values of the SS-χ2 item level diagnostic statistics were significant after Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiplicity; however, examination of the underlying tables of frequencies suggested that those χ2 values were large, not because of poor model fit, but rather because of confluences of small observed and expected values. As this is common in the large contingency tables, summed-scores by five response alternatives, on which those statistics are based, those items were retained.

A suggested short form of eight items was selected based on maximizing information over the latent trait using information curves and considering the item content to make sure the items represent several facets of social health. The short form items are identified with “x” in the “SF” column of Table 4. The online data supplement provides a table of the IRT scaled scores that correspond with each summed score for the short form (Table A4 in the online data supplement).

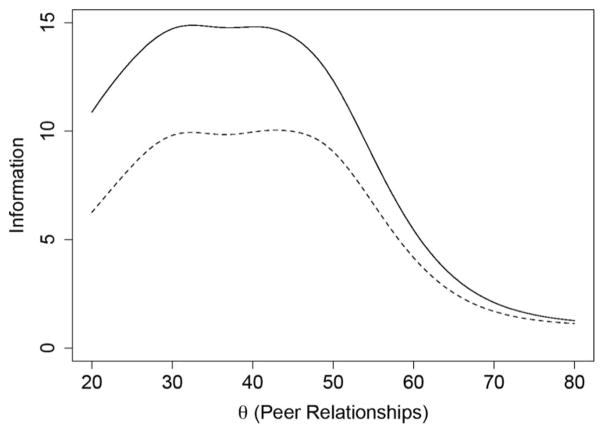

Figure 1 shows the total information curve for the 15-item pool (solid curve) and the information curve for the 8-item short form (dashed curve) plotted against the score continuum on the T score (mean 50, standard deviation 10) scale that is standard for PROMIS measures. Measurement precision is good for the lower range of individual differences in peer relationships, up to nearly a standard deviation above the mean for the entire pool, and somewhat less for the short form.

Figure 1.

The total information curve for the 15-item pool (solid curve) and the information curve for the 8-item short form (dashed curve).

Discussion

This study led to the development of a new self-report item bank measuring peer relationships for children 8 to 17 years old. Using factor analysis, these data did not confirm the initial hypothesis that there would be two subdomains, social function and sociability. Rather, the items that showed unidimensionality shared content related to the child’s relationships with target groups, including peers and adults. This analysis resulted in a unidimensional, self-report peer relationships item bank with associated item response theory-based calibrations.

The research team initially hypothesized that social health involved social function and sociability across several different types of relationships. During item development, the team recognized that many of children’s predominant social functions are reflected in their relationships with peers and adults. Indeed, in the focus groups leading to the development of the item banks, children with asthma commented on differential effects of illness on parental relationships versus peer relationships (Walsh et al., 2008). Factor analysis supported this, but the initial forms did not have sufficient items about relationships with adults to create an item bank. In the future, researchers could pursue adult relationships as a possible social health item bank. Regardless, peer relationships are critical for the development of good social health.

Peer relationships play a pivotal role in social development. Through peer relationships, children learn about social roles and gain invaluable interpersonal skills. The inability to develop healthy peer relationships is associated with a variety of behavioral problems, such as low academic achievement, substance use, depression, and difficulties with social adjustment and functioning in adulthood (Denham et al., 2009; Dirks, 2007; Hartup, 1989).

A child’s perception of the quality of peer relationships is one indicator of healthy social development. The study team’s aim was to design an item bank to assess children’s perceptions about their relationships across developmental stages. In doing this, the nature of the relationships (i.e., emotion vs. activity based) was not specified. As the factor analysis showed no differentiation by age, it appears that the PROMIS item bank is measuring an underlying foundation of peer relationships across development.

Reciprocity is present in peer relationships across developmental stages and is reflected in the peer relationships item bank (Hartup, 1989). In early and middle childhood, reciprocity means the sharing of toys and the ability to engage in play activities together. As people develop, reciprocity evolves to the capacity for a mutual exchange of emotional trust and loyalty (Hartup, 1989; Parker et al., 2006). Across developmental stages, reciprocity reflects the extent to which relational bonds are shared. Questions such as “Other kids wanted to be with me” and “I liked being around other kids my age” reflect both how the child perceives relationships with others as well as how the child feels others perceive the relationship. The PROMIS items on perceived reciprocity address the extent to which a child feels she or he belongs within the social context. A sense of social belongingness has a powerful effect on individuals throughout life, influencing the development of brain structure, immune function, and behavior, whereas a lack of perceived reciprocity in peer relationships, also viewed as a lack of belongingness, is a risk factor for later social and emotional issues (Bevans, Riley, & Forrest, 2010; Hartup, 1989).

Ultimately, the PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships item bank measures the youth’s perception of the quality of peer relationships. The bank of items was designed for use across the stages of social development. Other pediatric QOL self-report scales measure peer relationships, but through a slightly different lens. The KIDSCREEN-52 includes two social health scales, social support (six items) and social acceptance/bullying (three items), which measure an individual’s feelings of being included and supported as well as the experience of feeling tormented and rejected by peers (Ravens-Sieberer & European KIDSCREEN Group, 2006). The social functioning scale of the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales includes five items asking children and teens to report on the frequency of problems getting along with others their age (Varni et al., 2003). Finally, the child form of the CHQ (Children’s Health Questionnaire) contains three items about the extent to which a child’s behavior problems limit schoolwork or activities with friends (Landgraf et al., 1996). In choosing to use the PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships scale over one of these other scales, a researcher would be asking for a more focused look at children’s perceptions of their relationships with other kids their age.

Strengths of the Current Study

The PROMIS peer relationships item bank is unique in that it includes a pool of 15 positively framed items focused on the perceived quality and reciprocity of an individual’s peer relationships. Given the importance of peer relationships on social development, this bank makes an important contribution to the field, as it provides a comprehensive way of examining this aspect of social health. Systematic, rigorous psychometric analyses found that this bank effectively measured peer relationships for both children (ages 8–12) and teens (ages 13–17). The analytic advantage to having one item bank for all ages is that it allows for the comparison of results across age groups as well as the longitudinal use of the bank.

Utilizing IRT analysis to identify final items ultimately offers more flexibility for future users of the item bank. This approach allows researchers to select the most useful items for their study. The research team proposes an eight-item short form; however, a smaller subset of items from the item bank can also be used and scored on the same metric as the larger set. When using a smaller set of items, the precision of measurement will decrease, but the respondent burden is lower.

Limitations and Future Directions

Because the items were administered across several test forms, factor analyses could not be performed across the entire bank. This limitation makes it impossible to ensure that items from different forms do not exhibit local dependence. Additionally, it is possible that the results of factor analyses would have been different if all items were analyzed together. Instead, factor analysis was conducted over the subgroups of items tested on each form. Because the items were created based on content from qualitative work and were then randomly allocated to test forms, the different test forms can be viewed as replicated factor analyses, which increases confidence in the factor analytic results. Cross-sectional testing using the entire item pool is currently underway to verify these results.

A limitation that may be inherent in this measure of social health is the convolution of the measurement of individual differences in the propensity to endorse positively worded statements with the measurement of peer relationships. The factor analytic results suggest this convolution exists, and further, that there is no obvious way to avoid it. The additional measurement of individual differences in the propensity to endorse positively worded statements cannot be “cancelled” by adding negatively worded statements, because the factor analytic results indicated that tendency to endorse such negative items reflected a separate dimension of individual differences.

Future research may consider the development of a separate measure of relationships with adults. As mentioned previously, there appeared to be a separate dimension measuring children’s interactions with adults; however, there were not enough items to make a separate scale. Although assessment of child–adult interactions is often overlooked in the measure of children’s social health, existing conceptualizations of children’s social development emphasize the importance of adult relationships (e.g., parents, grandparents, and teachers; Denham et al., 2009; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Hartup, 1989), especially in early and middle childhood. In the focus groups described earlier, children commented on how their physical health affected relationships with family members and friends, and these effects with both groups were perceived as important (Walsh et al., 2008). Future researchers should expand the pool of possible adult relationships items for testing. These items could also be examined further in focus groups or cognitive interviews to explore how children of different ages and developmental stages conceptualize relationships with adults.

Another potential area for future research would be to develop items that better measure the higher end of functioning in peer relationships. While some constructs have a true theoretical upper ceiling (e.g., depression), the PROMIS peer relationships measure extends approximately one standard deviation above the mean before reaching a ceiling effect. It is possible that this item bank could be enriched with items that could extend the range to differentiate individuals with very high levels of competence in peer relationships.

Implications for Practice

Youth with a variety of psychological, behavioral, and physical disorders can face challenges in their social health and peer relationships (Dirks, 2007; Spieth, 1996). As the prevalence of children who exhibit psychological problems has increased and survival rates for children with chronic illnesses has improved, there is an increasing need for clinicians to address deficits in social health. The PROMIS peer relationships measure provides a tool for determining who may be at risk for problems in this area as well as assessing how treatment course and disease characteristics may affect peer relationships. Lower scores on this measure can identify children who are candidates for interventions, such as social skills training groups or counseling services. The measure can then be readministered to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions on peer relationships.

The PROMIS pediatric item banks were developed to provide accurate and efficient assessment of important domains of HRQOL for children, including social health, and more specifically, peer relationships. This sample provides initial calibrations of the PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships item bank and the creation of the corresponding PROMIS pediatric instruments, version 1.0. This self-report scale is also complemented by the existence of a compatible parent proxy-report version (Varni et al., 2012).

Future research should also aim at validating this item bank and exploring potential uses for this item bank in clinical research. Currently, several studies are examining whether the item bank is responsive to changes in health status of children that are hypothesized to affect their peer relationships.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PROMIS II was funded by cooperative agreements with a Statistical Center (Northwestern University, PI: David Cella, PhD, 1U54AR057951), a Technology Center (Northwestern University, PI: Richard C. Gershon, PhD, 1U54AR057943), a Network Center (American Institutes for Research, PI: Susan (San) D. Keller, PhD, 1U54AR057926) and 13 Primary Research Sites which may include more than one institution (State University of New York, Stony Brook, PIs: Joan E. Broderick, PhD and Arthur A. Stone, PhD, 1U01AR057948; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Heidi M. Crane, MD, MPH, Paul K. Crane, MD, MPH, and Donald L. Patrick, PhD, 1U01AR057954; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD and Karon Cook, PhD, 1U01AR052171; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, PI: Darren A. DeWalt, MD, MPH, 2U01AR052181; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PI: Christopher B. Forrest, MD, PhD, 1U01AR057956; Stanford University, PI: James F. Fries, MD, 2U01AR052158; Boston University, PIs: Stephen M. Haley, PhD and David Scott Tulsky, PhD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), 1U01AR057929; University of California, Los Angeles, PIs: Dinesh Khanna, MD and Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, 1U01AR057936; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, 2U01AR052155; Georgetown University, PIs: Carol. M. Moinpour, PhD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) and Arnold L. Potosky, PhD, U01AR057971; Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, PI: Esi M. Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, 1U01AR057940; University of Maryland, Baltimore, PI: Lisa M. Shulman, MD, 1U01AR057967; and Duke University, PI: Kevin P. Weinfurt, PhD, 2U01AR052186). NIH Science Officers on this project have included Deborah Ader, PhD, Vanessa Ameen, MD, Susan Czajkowski, PhD, Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Lawrence Fox, MD, PhD, Lynne Haverkos, MD, MPH, Thomas Hilton, PhD, Laura Lee Johnson, PhD, Michael Kozak, PhD, Peter Lyster, PhD, Donald Mattison, MD, Claudia Moy, PhD, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, William Riley, PhD, Ashley Wilder Smith, PhD, MPH, Susana Serrate-Sztein, MD, Ellen Werner, PhD and James Witter, MD, PhD. This article was reviewed by PROMIS reviewers before submission for external peer review.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Darren A. DeWalt, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David Thissen, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Brian D. Stucky, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California

Michelle M. Langer, National Conference of Bar Examiners, Madison, Wisconsin

Esi Morgan DeWitt, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Debra E. Irwin, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Jin-Shei Lai, Northwestern University.

Karin B. Yeatts, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Heather E. Gross, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Olivia Taylor, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

James W. Varni, Texas A&M University

References

- Ader DN. Developing the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Medical Care. 2007;45:S1–S2. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000260537.45076.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Butcher D, Iachini A, Amorose A. Initial reliability and validity of the Perceived Social Competence Scale. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;18:47–54. doi: 10.1177/1049731507304364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bevans KB, Riley AW, Forrest CB. Development of the healthy pathways child-report scales. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care, & Rehabilitation. 2010;19:1195–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Smith KJ, Edelen MO, Stone C, Thissen D, Sun X. IRTFIT: A macro for item fit and local dependence tests under IRT models. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R, Tateneni K, Mels G. CEFA: Comprehensive exploratory factor analysis, Version 2. 2004 Retrieved from http://faculty.psy.ohio-state.edu/browne/software.php.

- Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Rose M. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Factors influencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) generic core scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-58. 1477-7525-4-58[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Wyatt TM, Bassett HH, Echeverria D, Knox SS. Assessing social-emotional development in children from a longitudinal perspective. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63:I37–I52. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.070797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care. 2007;45:S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e200005650-200705001-00003[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitt EM, Stucky BD, Thissen D, Irwin DE, Langer M, Varni JW, Dewalt DA. Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: Built using item response theory. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012. S0895-4356(10)00364-1[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks MA, Treat TA, Weersing VR. Integrating theoretical, measurement, and intervention models of youth social competence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:327–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M. IRT from SSI: Bilog-MG, Multilog, Parscale, Testfact. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.2307/1130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt CA, Fairclough DL, Grossenbacher JC, Barrera M, Gilmer MJ, Foster TL, Vannatta K. Peer relationships of bereaved siblings and comparison classmates after a child’s death from cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37:209–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. Social relationships and their developmental significance. American Psychologist. 1989;44:120–126. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CD, Edwards MC, Thissen D, Langer MM, Wirth RJ, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Practical issues in the application of item response theory: A demonstration using Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Medical Care. 2007;45:S39–S47. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000259879.05499.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Stucky B, Langer MM, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Lai JS, DeWalt DA. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2010;19:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Lai JS, Dewalt DA. PROMIS Pediatric Anger Scale: An item response theory analysis. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2012;21:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9969-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Stucky BD, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Lai JS, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Sampling plan and patient characteristics of the PROMIS pediatrics large-scale survey. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2010;19:585–594. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9618-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Varni JW, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-3. 1477-7525-7-3[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8.5. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mackner LM, Vannatta K, Crandall WV. Gender differences in the social functioning of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2012;19:270–276. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell KW, Gimpel GA. Social skills of children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment and treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, du Toit S, Spisic D. Unpublished Tech Rep No. Los Angeles, CA: 1997. Robust interference using weighted least squared and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. MPlus user’s guide. 2. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noll RB, Kiska R, Reiter-Purtill J, Gerhardt CA, Vannatta K. A controlled, longitudinal study of the social functioning of youth with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1453–1459. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll RB, Reiter-Purtill J, Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, Short A. Peer relationships and emotional well-being of children with sickle cell disease: A controlled replication. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence. 2007;13:173–187. doi: 10.1080/09297040500473706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Thissen D. Further investigation of the performance of S - X2: An item fit index for use with dichotomous item response theory models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2003;27:289–298. doi: 10.1177/0146621603027004004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Thissen D. Likelihood-based item-fit indices for dichotomous item response theory models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2000;24:50–64. doi: 10.1177/01466216000241003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Rubin KH, Erath SA, Wojslawowicz JC, Buskirk AA. Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method. 2. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Sons; 2006. pp. 419–493. [Google Scholar]

- PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS Domain Framework–Social Health. n.d Retrieved April 24, 2012, from http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/domainframework3.

- Ravens-Sieberer U European KIDSCREEN Group. The KIDSCREEN questionnaires: Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents handbook. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publisher; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Cella D. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Medical Care. 2007;45:S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Waller NG. Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:27–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L. The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development. 1997;6:111–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika. 1970;35:139. doi: 10.1007/BF02290599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Graded response model. In: van der Liden WJ, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of modern item response theory. New York, NY: Springer; 1997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spieth LE, Harris CV. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21:175–193. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA. One social world: The integrated development of parent-child and peer relationships. In: Collins WA, Laursen BP, editors. Relationships as developmental contexts. Vol. 30. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, Inc; 1999. pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Thissen D. Using effect sizes for research reporting: Examples using item response theory to analyze differential item functioning. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:402–415. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.402. 2006-22258-005[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D. Documentation for a computer program. Thurston Psychometric Laboratory, University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill: 2001. IRT-LR-DIF v2.0b: Software for the computation of the statistics involved in item response theory likelihood-ratio tests for differential item functioning. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Nelson L, Rosa K, McLeod LD. Item response theory for items scored in two categories. In: Thissen D, Wainer H, editors. Test scoring. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 73–140. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Wainer H. Detection of differential item functioning using the parameters of item response models. In: Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 67–113. [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2003;3:329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:TPAAPP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, Dewitt EM, Irwin DE, Lai JS, Dewalt DA. PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale: An item response theory analysis of the Pediatric Pain Item Bank. Journal of Pain. 2010;11:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.005. S1526-5900(10)00326-3[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, Liu Y, Gorder H, Irwin DE, Dewalt DA. PROMIS((R)) Parent Proxy Report Scales: An item response theory analysis of the parent proxy report item banks. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2012;21:1223–1240. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh TR, Irwin DE, Meier A, Varni JW, DeWalt DA. The use of focus groups in the development of the PROMIS Pediatrics Item Bank. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2008;17:725–735. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9338-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigelsworth M, Humphrey N, Kalambouka A, Lendrum A. A review of key issues in the measurement of children’s social and emotional skills. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2010;26:173–186. doi: 10.1080/02667361003768526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams V, Jones LV, Tukey JW. Controlling error in multiple comparisons, with examples from state-to-state differences in educational achievement. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:42–69. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Yeatts KB, Stucky B, Thissen D, Irwin D, Varni JW, DeWitt EM, DeWalt DA. Construction of the Pediatric Asthma Impact Scale (PAIS) for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Journal of Asthma. 2010;47:295–302. doi: 10.3109/02770900903426997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.