Abstract

Social and demographic trends are placing an increasing number of adults at risk for loneliness, an established risk factor for physical and mental illness. The growing costs of loneliness have led to a number of loneliness reduction interventions. Qualitative reviews have identified four primary intervention strategies: 1) improving social skills, 2) enhancing social support, 3) increasing opportunities for social contact, and 4) addressing maladaptive social cognition. An integrative meta-analysis of loneliness reduction interventions was conducted to quantify the effects of each strategy and to examine the potential role of moderator variables. Results revealed that single group pre-post and non-randomized comparison studies yielded larger mean effect sizes relative to randomized comparison studies. Among studies that used the latter design, the most successful interventions addressed maladaptive social cognition. This is consistent with current theories regarding loneliness and its etiology. Theoretical and methodological issues associated with designing new loneliness reduction interventions are discussed.

The formation of meaningful social connections is an integral part of human nature (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). Some individuals have difficulty forming meaningful social connections whereas others form such social connections but lose them through separation, widowhood, or other vagaries of life. Individuals without meaningful social connections are at risk for loneliness, an aversive experience that all humans experience at one time or another. Although the health consequences of persistent loneliness are on par with that of many psychiatric illnesses, our understanding of the origins and treatment of loneliness is still limited (O’Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008). To properly treat loneliness, a better understanding of the nature and mechanisms underlying loneliness is needed. Therefore, the goals of this paper are to review the definitions, prevalence, health effects, and current theories regarding loneliness, to describe the relationship between these theories and previous studies of loneliness reduction strategies, and to use meta-analytic techniques to quantify the loneliness-reducing effects of studies which meet our analysis criteria.

Definitions

Loneliness is typically defined as the discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual social relationships (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). Although sometimes considered synonymous with social isolation, loneliness and social isolation are related but distinct concepts. The latter reflects an objective measure of social interactions and relationships, whereas loneliness reflects perceived social isolation or outcast. Accordingly, loneliness is more closely associated with the quality than the number of relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Wheeler, Reis, & Nezlek, 1983). The importance of relationship quality takes origin in the fundamentally social nature of the human species. Both phylogenetically and ontogenetically, humans require not simply the presence of others but the presence of others who value them, whom they can trust, and with whom they can communicate, plan, and work together to survive, prosper, and care for our offspring sufficiently long that they too reproduce (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). As a result, an individual may be lonely in a crowd or socially contented while alone.

Loneliness was traditionally thought to be a gnawing sensation or chronic distress without redeeming features (Weiss, 1973), but more recently loneliness has been conceptualized as a biological construct, a state that has evolved as a signal to change behavior – very much like hunger, thirst, or physical pain – that serves to help one avoid damage and promote the transmission of genes to the gene pool (Cacioppo et al., 2006). That is, loneliness has been posited to be an aversive signal that motivates us to become sensitive to potential social threats and to renew the connections needed to survive and prosper. Like hunger, thirst, and pain, loneliness is typically mild and transient because it contributes to the maintenance or repair of meaningful social connections – as occurs when a child is reunited with his or her parent following separation or a spouse returns home following a trip. When meaningful social connections are perceived as severed or unavailable, however, loneliness can produce deleterious effects on cognition and behavior (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2005) that, in turn, increase the likelihood that loneliness becomes chronic (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; Young, 1982). Interventions to reduce loneliness have been developed because the chronic form of loneliness is highly aversive (Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Weiss, 1973), is a significant risk factor for mental and physical health problems (Danese et al., 2009; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2007), and adversely affects others around them (Berscheid & Reis, 1998; Cacioppo, Fowler, & Christakis, 2009).

Weiss distinguished between emotional and social loneliness on theoretical grounds (Weiss, 1973). Various factor analytic studies have provided some evidence that the experience of loneliness can be partitioned into separable dimensions (Hawkley, Browne, & Cacioppo, 2005; Knight, Chisholm, Nigel, & Godfrey, 1988; McWhirter, 1990a), but these factors have also been found to be highly correlated and their antecedents and consequences have been found to be sufficiently overlapping that loneliness is generally conceptualized and measured as a unidimensional construct (Hawkley, Browne, & Cacioppo, 2005; Russell, 1996; Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980).

Prevalence

Research reveals a significant prevalence of loneliness among both children and adults. In a study of kindergarteners and first graders, 12% reported feeling lonely at school (Cassidy & Asher, 1992). Among third through sixth-grade children, 8.4% scored in the lonely range using the Asher et al. Loneliness Scale (Asher, Hymel, & Renshaw, 1984; Asher & Wheeler, 1985). Among middle-aged and older adults, from five to seven percent report feeling intense or persistent loneliness (Steffick, 2000; Victor, Scambler, Bowling, & Bondt, 2005) and up to 32% of adults over age 55 report feeling lonely at any given time (De Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 1999). According to the 2002 Health and Retirement Survey, 19.3% of U.S. adults over age 65 reported feeling lonely for much of the previous week (Theeke, 2009). Several factors suggest the prevalence of loneliness could increase in the coming decades. One is the aging of the U.S. population. In 1900, 4.1% of Americans were 65 years or older. By 2006, that percentage had increased to 12.4%, representing 37.3 million Americans (Administration on Aging, 2008). Older age is associated with disability-related obstacles to social interaction as well as with longer periods of time living as widows or widowers. Moreover, delayed marriage (Goldstein & Kenney, 2001), increased dual career families (Schneider & Waite, 2005), increased single-residence households (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2003), and reduced fertility rates (Taylor et al., 2010) may also contribute to an increased prevalence of loneliness and its associated health effects.

Health Effects

The associations between loneliness and physical and mental health indicate that loneliness influences virtually every aspect of life in our social species. For example, loneliness not only involves painful feelings of isolation, disconnectedness from others and not belonging (Hawkley, Browne, & Cacioppo, 2005) but it is also a risk factor for myriad health conditions, including increased vascular resistance in young adults (Cacioppo, Hawkley, Crawford et al., 2002; Hawkley, Burleson, Berntson, & Cacioppo, 2003), elevated systolic blood pressure in older adults (Cacioppo, Hawkley, Crawford et al., 2002; Hawkley, Masi, Berry, & Cacioppo, 2006; Hawkley, Thisted, Masi, & Cacioppo, 2010), less restorative sleep (Cacioppo, Hawkley, Berntson et al., 2002; Hawkley, Preacher, & Cacioppo, 2010), increased hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical activity (Adam, Hawkley, Kudielka, & Cacioppo, 2006), diminished immunity (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984; Pressman et al., 2005), under-expression of genes bearing anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid response elements (Cole et al., 2007), and abnormal ratios of circulating white blood cells (e.g., neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes) (Cole, 2008). In addition, longitudinal analysis reveals that adults who were socially isolated as children are more likely to have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including overweight, high blood pressure, high total cholesterol, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high glycated hemoglobin, and low maximum oxygen consumption (Caspi, Harrington, Moffitt, Milne, & Poulton, 2006), as well as elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (Danese et al., 2009).

Compared to non-lonely individuals, lonely people are also more likely to suffer from cognitive decline (Tilvis et al., 2004) and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (Wilson et al., 2007). Animal studies are beginning to shed light on the mechanism by which these effects may occur. Among mice, social isolation reduces central anti-inflammatory responses and increases infarct size following induction of stroke (Karelina et al., 2009). In addition, socially isolated animals demonstrate less dendritic arborization in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Silva-Gomez, Rojas, Juarez, & Flores, 2003) as well as decreased production of brain-derived neurotropic factors (Barrientos et al., 2003). Whereas it is unknown whether similar effects occur in humans, experimental manipulation that leads people to believe they face a future of social isolation has been shown to impair executive functioning. Compared to controls, the “future alone” group performed similarly on a rote memorization task but consumed more delicious but unhealthy foods (Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005) and were more aggressive toward others (Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001). Therefore, perceived future isolation did not reduce routine mental ability but rather impaired higher order executive functioning related to food consumption and social interaction.

Loneliness impairs executive functioning in part because it triggers implicit hypervigilance for social threats (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Heightened sensitivity to social threats results in biases in attention and cognition toward negative aspects of the social context. These social cognitions subtly influence behaviors, social interactions, and affect in a confirmatory fashion that exacerbates feelings of sadness and loneliness. Maladaptive social cognitions have consequences for mental health and well-being. Loneliness has been shown to predict depressive symptoms (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, in press; Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006) and suicidal ideation and behavior (Rudatsikira, Muula, Siziya, & Twa-Twa, 2007). The impact of loneliness on such diverse aspects of physical and mental health provides justification for interventions to mitigate this experience.

Theories of Loneliness

As described above, loneliness can be a fleeting, unpleasant mood for some individuals or a persistent, aversive experience for others. Most people are capable of feeling loneliness acutely, but some are unable to escape the grip of loneliness. Research indicates that loneliness is approximately 50% heritable and 50% environmental (Boomsma, Willemsen, Dolan, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2005; McGuire & Clifford, 2000). For a species to survive, not only must one generation procreate, but the offspring of that generation must procreate as well. Human offspring have the longest period of dependency of any species and rely upon their parents to feed and protect them for many years. During hunter-gatherer times, survival of children to reproductive age would have depended on parents sharing food and resources with their children even if at cost to themselves. Parents who felt no ‘pangs’ of loneliness when parted from their children would have been less likely to maintain nurturing and protective parental connections compared to parents who experienced distress when separated from the family and tribe. Thus, whereas loneliness is unpleasant for the individual, it may be essential for species survival (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Because infant attachment is not predictive of adult attachment and adult attachment can change, childhood attachment appears not to be a major determinant of loneliness in most adults (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008; Shaver, Furman, & Buhrmester, 1985).

Of course, having a gene or genes for loneliness does not mean an individual will be lonely. What appears to be inherited is the level of distress aroused by social disconnection. For individuals of all ages, loneliness may arise upon moving to a new city, losing a friend, or losing a loved one. Analysis of data from a population-based, racially diverse sample of men and women aged 50 through 68 revealed several factors were positively associated with loneliness. These included number of physical symptoms, chronic stress from employment, and chronic stress from social life and recreation. Factors negatively associated with loneliness included social network size, satisfaction with social network, and having a spousal confidant (Hawkley et al., 2008). These results suggest that the success of interventions to reduce loneliness may hinge upon the degree to which one’s social environment and social interactions are improved.

Research over the past several decades has shaped our understanding of the nature of loneliness. Early studies focused on individual differences between lonely and non-lonely people. This research demonstrated that compared to the non-lonely, lonely individuals approach social encounters with greater cynicism and interpersonal mistrust (Brennan & Auslander, 1979; Jones, Freemon, & Goswick, 1981; Moore & Sermat, 1974), rate others and themselves more negatively, and are more likely to expect others to reject them (Jones, 1982). In addition, lonely people have lower feelings of self-worth (Peplau, Miceli, & Morasch, 1982), tend to blame themselves for social failures (Anderson, Horowitz, & French, 1983), are more self-consciousness in social situations (Cheek & Busch, 1981), and adopt behaviors that increase, rather than decrease, their likelihood of rejection (Horowitz, 1983). This “individual differences” model of loneliness has influenced loneliness reduction interventions to date. Specifically, these interventions have attempted to correct deficits in social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, and/or maladaptive social cognition.

More recent research suggests that loneliness is not an immutable trait but rather can be exacerbated or ameliorated by social interactions. In an illustrative study, hypnosis was successfully used to induce participants to feel high and low levels of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Increasing feelings of loneliness also increased feelings of shyness, anxiety and anger, and decreased feelings of social skills, optimism, self-esteem, and social support, suggesting that loneliness is syndrome-like in carrying with it a range of attributions, expectations, and perceptions that reinforce feelings of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Conversely, these findings suggest that interventions that enhance a feeling of social connectedness can alter self-and other-perceptions along dimensions that have the potential to improve the quality of social interactions and relationships and keep loneliness at bay.

To examine the role of the social context in loneliness, investigators studied loneliness in the Framingham Heart Study (Cacioppo, Fowler, & Christakis, 2009). Using social network analysis and self-reported data from over 6,000 participants between 1983 and 2001, the authors identified several unique phenomena. Specifically, they found that lonely people tend to be linked to other people who are lonely, an effect that is stronger for geographically proximal friends but extends to three degrees of separation. In addition, non-lonely individuals who are around lonely individuals tend to grow lonelier over time. This suggests that loneliness can be induced and operates not unlike a biological contagion. Finally, analysis revealed that lonely individuals were consistently moved to the periphery of social networks, as if they had been metaphorically pushed there by others in the network. From an evolutionary perspective, such marginalization may protect the structural integrity of the network. These findings also go beyond the individual differences model of loneliness and demonstrate the power not only of social networks but the ability of people who become lonely to have a negative effect on non-lonely people.

A mechanism for the contagion of loneliness may lie in the reciprocal effects of social interaction quality and affect. In an experience sampling study, 134 undergraduates were queried regarding their psychosocial and behavioral states at nine random times during the day on seven consecutive days (Hawkley, Preacher, & Cacioppo, 2007). Information regarding the positivity or negativity of their affect and their interactions (if they were interacting with someone at the time their programmable watched beeped) was collected via diary entries. Of primary interest was the ability of loneliness to predict variability in affect and interaction quality and their interrelationship. Using multilevel modeling, the authors found that loneliness was associated with decreased positivity and increased negativity in affect and interaction quality across all measurement occasions. In longitudinal analysis, positive and negative interaction quality predicted subsequent positive and negative affect, and in a reciprocal causal fashion, positive and negative affect predicted subsequent interaction quality. Moreover, the influence of interaction negativity on negative affect persisted over a longer duration than the influence of interaction positivity on positive affect. In addition, negative affect influenced subsequent interaction positivity and negativity, whereas positive affect influenced only subsequent interaction positivity. Finally, loneliness was characterized by greater negative affect and more negative interactions. Together, this pattern of results suggests that lonely individuals not only communicate negativity to others but also elicit it from others and transmit it through others. This perpetuates a cycle of negative interactions and affect in the lonely individual and also transmits negativity to others to affect their interactions as well. These results may explain the mechanism by which lonely individuals increase feelings of loneliness among those with whom they interact. The authors concluded that interventions that reduce perceptions of negativity in interactions or affect have the potential to break the cycle of negativity that people experience when lonely.

Taken together, these studies suggest that when individuals feel lonely, they think and act differently than when they do not feel lonely. Accordingly, their perceptions of the social environment, their social cognitions, and their interpersonal actions have all been targeted in interventions to reduce loneliness.

Previous Reviews of Loneliness Interventions

Since 1984, six papers have reviewed the literature regarding strategies to reduce loneliness, social isolation, or both. Of these reviews, all are qualitative, rather than quantitative, and most explicitly or implicitly discuss four primary strategies of loneliness reduction interventions: 1) improving social skills, 2) enhancing social support, 3) increasing opportunities for social interaction, and 4) addressing maladaptive social cognition. Because the number of friends or social interactions is not as predictive or loneliness as the quality of their relationships, increasing opportunities for social interaction and enhancing social support may address social isolation more than loneliness. In contrast, improving social skills and addressing maladaptive social cognition focus on quality of social interaction and therefore address loneliness more directly. All of the reviews identified both successful and unsuccessful loneliness reduction strategies, and five of the six reviews concluded that loneliness can be mitigated with specific interventions. However, all of the reviews concluded that questions remain regarding the efficacy of interventions and that more rigorous research is needed in this area.

The earliest review cited over 40 loneliness reduction interventions dating back to the 1930’s (Rook, 1984). Most of these interventions fell into the four categories described above. Depending upon the study, interventions to improve social skills emphasized one or several of the following: conversational skills, speaking on the telephone, giving and receiving compliments, handling periods of silence, enhancing physical attractiveness, nonverbal communication methods, and approaches to physical intimacy. In one study, a social skills intervention among lonely college students was associated with decreased loneliness, self-consciousness, and shyness compared to two control groups (Jones, Hobbs, & Hockenbury, 1982). Among interventions that enhanced social support, professionally-initiated interventions for the bereaved (Vachon, Lyall, Rogers, Freedman-Letofsky, & Freeman, 1980), for the elderly whose personal networks had been disrupted by relocation (Kowalski, 1981), and for children whose parents had divorced (Wallerstein & Kelly, 1977) all demonstrated loneliness reductions. Increasing opportunities for social interaction also reduced loneliness in some studies. An example is a blood pressure evaluation program conducted in the lobbies of single-room occupancy hotels that housed older individuals. Although the residents tended to stay in their rooms due to physical disability and fear of crime, the program increased social interaction in the lobbies, and over time, helped participants identify shared interests (Pilisuk & Minkler, 1980). Another example involved isolated seniors working together to collect and distribute food for the needy. As the study progressed, the seniors formed informal support networks (Pilisuk & Minkler, 1980). Finally, programs that focused on maladaptive social cognition through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) appeared somewhat successful in reducing loneliness (Young, 1982). The cornerstone of this intervention was to teach lonely individuals to identify automatic negative thoughts and regard them as hypotheses to be tested rather than facts. Rook (1984) acknowledged that many of the studies in her review were not successful or lacked experimental rigor but indicated that interventions that focused on social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, and social cognition held promise for reducing loneliness.

A 1990 review also identified social skills training, opportunities for social interaction, and CBT as potentially effective in reducing loneliness (McWhirter, 1990b). The author noted that whereas social skills training was initially developed to reduce anxiety and shyness, it has been successfully adapted to treat loneliness (Twentyman & Zimering, 1979). Other programs have achieved success by providing individuals with opportunities to find others with common goals and by arranging activities of interest for small groups of lonely individuals (Cutrona & Peplau, 1979). McWhirter (1990b) referred to several CBT-based studies that succeeded in reducing loneliness (Anderson & Arnoult, 1985; Anderson, Horowitz, & French, 1983; Young, 1982). Some studies even showed that combining CBT with social skills training was more effective in treating lonely and socially anxious adults than either treatment alone (Glass, Gottman, & Shmurak, 1976; Rook & Peplau, 1982).

A third review examined twenty-one interventions designed to reduce loneliness among older individuals (Cattan & White, 1998). Although references to the specific interventions were not provided, the authors grouped them into four categories: 1) group activities, 2) one-to-one interventions 3) service delivery, and 4) whole community approaches. Taking design quality into consideration, the authors concluded that the most effective interventions included group activities, self-help, or bereavement support, targeted specific groups (e.g., women and widowers), used more than one intervention strategy, had an evaluation that coincided with the intervention, and gave participants some level of control. The lone study that evaluated a community approach was deemed inconclusive due to poor study design.

A subsequent review identified 17 loneliness reduction interventions published between 1982 and 2002 (Findlay, 2003). This report used a classification scheme similar to that of Cattan & White (1998) (e.g., group interventions, one-to-one interventions, service provision, and Internet usage). Although this typology does not perfectly match that of Rook (1984) or McWhirter (1990), most of the studies addressed social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, or social cognition. For example, the one-to-one interventions included telephone-based and gatekeeper programs designed to enhance social interaction and social support, respectively. Similarly, the group interventions included teleconferencing, support groups, and friendship enrichment training, which were also designed to improve social interaction and social skills. The service provision interventions focused on social support whereas the Internet programs represented an approach to increasing opportunities for social interaction. Whereas some of the programs in this review showed benefit, Findlay (2003) noted that many were flawed by weak study design. For example, only six of the 17 studies were randomized controlled trials. As a result, this review concluded there was little evidence to support the notion that interventions can reduce loneliness among older people.

Cattan et al. (2005) conducted a qualitative review of studies published between 1970 and 2002 and found 30 papers that evaluated loneliness prevention interventions among older adults (Cattan, White, Bond, & Learmouth, 2005). In this review, the authors used their previous typology (e.g., group activities, one-to-one counseling, service provision, and community development). These categories were further refined to include group activities with an educational component; group interventions to provide social support; home visits to provide assessment, information, or social services; home visits or telephone contact to provide directed support or problem solving; and one-on-one interventions to provide social support. As in previous reviews, these interventions addressed social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, and social cognition. Because only 16 of the 30 studies were randomized controlled trials, Cattan et al. (2005) also highlighted the dearth of methodological rigor among loneliness reduction interventions. Nonetheless, of the 13 studies considered to be of high quality, six were considered effective, one was considered partially effective, five were considered ineffective, and one was considered inconclusive. Consistent with their previous review, Cattan et al. (2005) concluded that the most effective programs were group interventions that included an educational component or a targeted activity, targeted specific groups (e.g., women, care-givers, the widowed, the physically inactive, or people with serious mental health problems), tested a representative sample of the intended target group, and enabled some level of participant and/or facilitator control.

The final review examined 36 studies and focused on persons with severe mental illness, a population whose prevalence of loneliness is approximately twice that of the general population (Perese & Wolf, 2005). Interventions to reduce loneliness in this group were similar to those developed for the general population, including social skills training, enhanced social support, increased opportunities for social interactions, and cognitive behavioral training. Support groups were noted to be the primary method for social skills training in this population. In one study, this approach was associated with a decline in unmet needs for friends (Perese, Getty, & Wooldridge, unpublished). In contrast, mutual-help groups represented the primary strategy for enhancing social support among those with mental illness. Although few studies have evaluated this approach, one study found mutual-help groups reduced psychiatric symptoms, hospitalizations, and social isolation among the mentally ill (Galanter, 1988).

According to Perese & Wolfe (2005), one way to increase opportunities for social interaction is befriending, which “aims to develop a relationship between individuals that is distinct from professional/client relationships”(Cox, 1993). Originally developed to reduce loneliness, its goals have grown to include improving quality of life, reducing social isolation, helping people meet emotional needs, and promoting and maintaining mental health (Andrews, Gavin, Begley, & Brodie, 2003). Although befriending appears to reduce social isolation, studies to date have not assessed the effect of befriending on loneliness among individuals with mental illness or the general population. Finally, deficits in social cognition were addressed through self-help groups, which attempted to change thinking from negative and fearful to positive and self-supportive (Murray, 1996). The self-help groups in this review focused on problems brought up by members and on coping techniques taught by professional group leaders. The review noted that little research has assessed the efficacy of this approach. However, one study found that family members who attended self-help groups reported improvements in their relationships with mentally ill family members (Heller, Roccoforte, Hsieh, Cook, & Pickett, 1997).

In summary, six previous qualitative reviews of loneliness reduction studies identified both successful and unsuccessful interventions. Five of the reviews concluded loneliness could be reduced with certain interventions but one concluded there was little evidence that current techniques can reduce loneliness, especially among lonely elders (Findlay, 2003). In three of the reviews, interventions were explicitly classified as addressing social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, or impairments in social cognition (McWhirter, 1990b; Perese & Wolf, 2005; Rook, 1984). In the other three reviews, this classification was implicit, although not all reviews included studies that addressed impaired social cognition (Cattan & White, 1998; Cattan, White, Bond, & Learmouth, 2005; Findlay, 2003). All of the reviews noted a dearth of randomized controlled trials and all called for increased rigor in evaluating loneliness reduction interventions.

Purpose of the Meta-Analysis

The goal of this meta-analysis is to provide the rigor called for by previous reviews and quantify the efficacy of the primary intervention strategies. Although previous reviews suggested that certain interventions can reduce loneliness, the results were mixed and a significant number of interventions were not associated with loneliness reduction. It may be that the success of certain interventions was due more to study design than to the quality of the intervention. For example, pre-post studies, non-randomized group comparison studies, and randomized group comparison studies are inequivalent designs in terms of comparing effect sizes (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Using meta-analysis, mean effect sizes can be compared across study designs and within groups of studies of the same design. Within study design, heterogeneity of effect sizes can be assessed and, when evident, examined to determine whether efficacy varies as a function of intervention format (group-based versus individual-based), intervention mode (technology-based versus non-technology-based), the type of loneliness measure used, the frequency and duration of the intervention, and the age and sex of the study participants. Each of these variables has the potential to influence intervention efficacy and the studies we reviewed provided data regarding these characteristics. We did not evaluate marital status as a potential moderator because very few studies provided data on this variable.

Interventions to date have relied upon an “individual differences” model, in which the lonely were considered to have deficits in social skills, social support, opportunities for social interaction, and/or social cognition. Given recent insights regarding the centrality of social cognition to loneliness (Cacioppo, Fowler, & Christakis, 2009; Cacioppo et al., 2006; Hawkley, Preacher, & Cacioppo, 2007), we hypothesized that interventions that address maladaptive social cognition will have a greater impact than those which address social skills, social support, or opportunities for social interaction.

Method

Selection of Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

Applying recently published guidelines for meta-analysis (APA Publications and Communications Board Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards, 2008), the literature review identified trials that specifically targeted loneliness among adults, adolescents, and/or children. PubMed and PsycINFO were searched for relevant studies using combinations of the following keywords: loneliness, intervention, treatment, prospective, medication, and pharmacology. Eligible studies had to be published from 1970 through September 2009, in English, in a peer-reviewed journal or doctoral dissertation, designed as an intervention specifically to lower loneliness, and had to measure loneliness quantitatively.

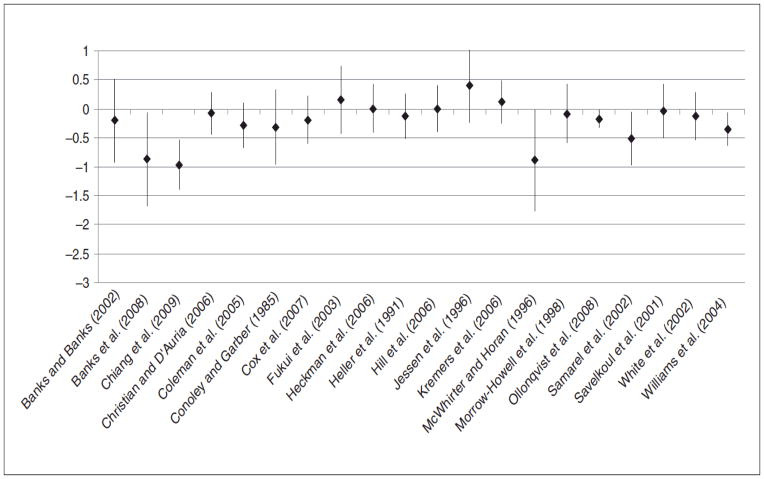

The initial search produced a total of 818 references in Medline and 777 references in PsycINFO, with significant duplication in references between the sources. As shown in Figure 1, the abstracts of 928 unique references were reviewed and 772 were excluded for lack of relevance based upon the abstract. The remaining 156 studies were reviewed in detail. Of these, 12 studies were excluded because they were descriptive reviews that did not assess loneliness interventions either qualitatively or quantitatively. However, two additional studies were identified in these reviews. This resulted in 146 studies that were further evaluated. Of these, 78 did not meet our initial inclusion criteria. A request for relevant studies posted on the listserv for the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (spsp-announce-l@list.cornell.edu) failed to generate any additional eligible studies. E-mail requests to individual authors in North America and Europe known to conduct research on loneliness elicited only one positive response. T. Fokkema indicated that a paper had been published in 2007, in the Dutch language, that reported the results of 18 loneliness interventions conducted among older adults in the Netherlands (Fokkema & van Tilburg, 2007). The authors forwarded an English version of the manuscript (Fokkema & van Tilburg, unpublished) and nine of the studies described met our initial inclusion criteria. Adding these studies to the others that met our initial criteria yielded 77 studies, which were then evaluated to determine whether they met established meta-analytic criteria.

Figure 1.

Identification of eligible studies for meta-analysis

Meta-Analytic Criteria

The first criterion for inclusion in the meta-analysis was that the intervention had to directly target loneliness. Seven studies were excluded because the interventions were directed at stress relief (Whitehouse et al., 1996), anxiety and/or depression (Mynatt, Wicks, & Bolden, 2008; Ransom et al., 2008), or health behaviors (de Craen, Gussekloo, Blauw, Willems, & Westendorp, 2006; Hedberg, Wikstrom-Frison, & Janlert, 1998; Hopman-Rock & Westhoff, 2002; Soholt Lupton, Fonnebo, Sogaard, & Fylkesnes, 2005). One study (Hu, 2009) examined the effect of an intervention on an induced state of loneliness, and was excluded from the analysis because induced loneliness is not comparable to the loneliness targeted in other included studies. In addition, the Wish Fulfillment study (Fokkema & van Tilburg, 2007) was excluded for lack of adequate information regarding the nature of the intervention. The second criterion was that the intervention effect had to be measured and reported quantitatively to enable the calculation of effect size. Although twelve studies originally failed to meet this criterion (Andersson, 1985; Brown, Allen, Dwozan, Mercer, & Warren, 2004; Clarke, Clarke, & Jagger, 1992; Evans & Jaureguy, 1982; Evans, Smith, Werkhoven, Fox, & Pritzl, 1986; Jones, Hobbs, & Hockenbury, 1982; McLarnon & Kaloupek, 1988; Routasalo, Tilvis, Kautiainen, & Pitkala, 2009; Seepersad, 2005; Stewart, Reutter, Letourneau, & Makawarimba, 2009; van Kordelaar, Stevens, & Pleiter, 2004; van Rossum et al., 1993), attempts to recover quantitative data from the authors were successful in two cases (Evans, Smith, Werkhoven, Fox, & Pritzl, 1986; Seepersad, 2005). The third criterion was that each study had to report original data not reported in another paper to avoid inflating effect sizes. Two studies were excluded based on this criterion. One study (Stevens, Martina, & Westerhof, 2006) was excluded because it duplicated data and because more complete results were reported in Martina and Stevens (2006), which was already included as an eligible study. Similarly, the other study (Add LUSTRE to your life, in Fokkema & van Tilburg, 2007) was excluded because a more detailed data of the same intervention was reported in Kremers, Steverink, Albersnagel, & Slaets (2006), which was already included. The fourth criterion was that the intervention had to involve a treatment group, not individual cases. On this basis, one study was excluded because the study focused on only two participants (Guevremont, MacMillan, Shawchuck, & Hansen, 1989). A total of 50 studies ultimately qualified for meta-analysis.

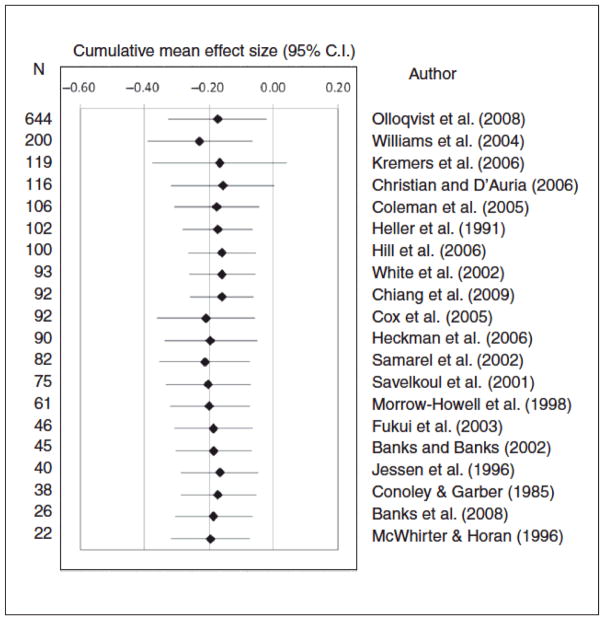

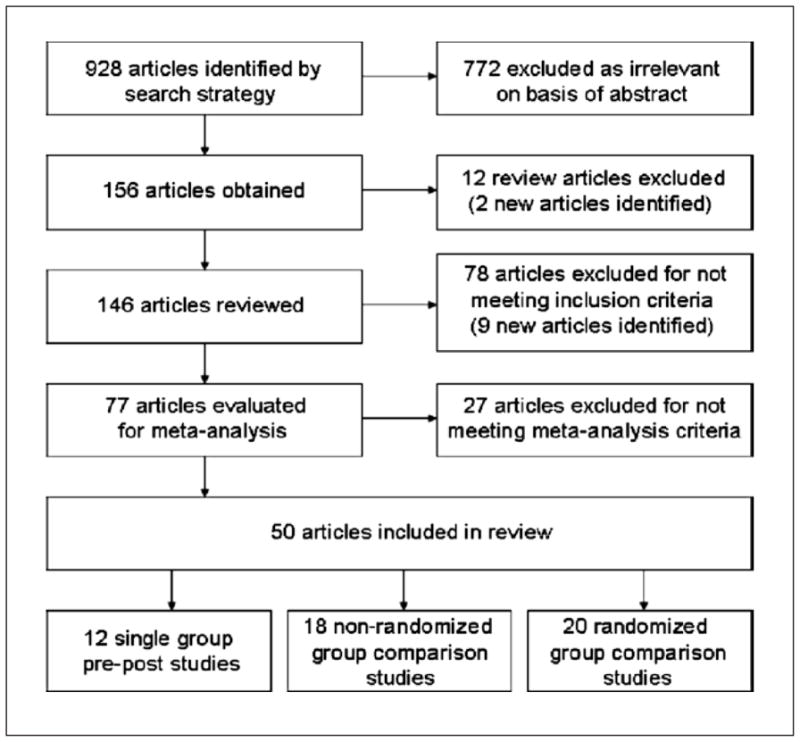

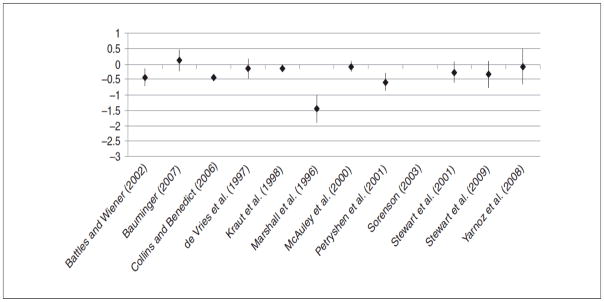

Because the effect size obtained from a single group pre-post study has a different meaning than the effect size calculated as the difference between two separate groups (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001), and because the effect size from a non-randomized group comparison often provides a less satisfactory estimate of the true effect size than a randomized group comparison study, the studies were categorized based on research design and a meta-analysis was conducted within each research design type. Of the 50 interventions, 12 were single group pre-post studies, 18 were non-randomized group comparison studies, and 20 were randomized group comparison studies.

Coded Variables

Key characteristics of the included studies are provided, by design type, in Tables 1–3. These tables provide effect sizes and information employed in moderator analyses, including mean age of the sample (as reported1 or as inferred when means were not reported2), gender composition (percent females, as reported or calculated3), intervention duration (in weeks, available for all but four studies4), intervention frequency (which was converted to total number of sessions for analysis purposes, and was calculable for all but fourteen studies5), type of loneliness measure (e.g., UCLA Loneliness Scale, DeJong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, other6), intervention format and mode (e.g., individual- or group-based and non-technology or technology-based, respectively), and intervention type (social skills training, enhanced social support, increased opportunity for social interaction, or social cognitive training). Intervention format was categorized as individual-based if the intervention was implemented on a one-on-one basis, and as group-based if more than one person participated in the intervention at the same time or if the intervention involved asynchronous interactions such as Internet-based chat room exchanges. Intervention mode was classified as technology-based if a telephone or computer was used to facilitate the intervention. Intervention type was categorized as 1) social skills training if the intervention focused on improving participants’ interpersonal communication skills, 2) as enhancing social support if the intervention offered regular contacts, care, or companionship, 3) as social access if the intervention increased opportunities for participants to engage in social interaction (e.g., online chat room or social activities), and 4) as social cognitive training if the intervention focused on changing participants’ social cognition. Importantly, intervention type was not confounded with study design: each intervention type was represented in each study design group (with the one exception that pre-post studies did not include a social skills intervention).

TABLE 1.

Single Group, Pre-Post Studies (N = 12)

| Authors | Enrollment Eligibility and Sample Size | Intervention Type and Duration | Effect Size (95% CI) | Intervention format | Intervention mode | Sample age | Sample % female | Loneliness Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Battles & Wiener, 2002) | Seriously ill children visiting the National Institutes of Health for treatment of chronic medical conditions. Participants recruited from NIH playrooms by a recreation therapist, principal investigator, or research assistant. N=32. | Social access: Virtual environment designed to provide an interactive online community in which children played games, learned about their medical condition, or talked with other chronically ill children. Participants completed four 1-hour sessions over a period of 6 to 9 months. | −0.43 (−0.72, −0.14) | Individual | TECH | 8–19 yrs; mean=14 | 47% | 8 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Bauminger, 2007) | Children who attended schools in middle-class, large urban areas and who had a prior clinical diagnosis of either high functioning autism or Asperger’s Syndrome. Schools and children were recruited through the Special Education Department in the Israeli Ministry of Education. N=19. | Social cognitive training: Cognitive-behavioral-ecological program conducted in each child’s school, implemented by the child’s main teacher, and involved one typically developing older peer and the child’s parents. Each child completed a cognitive behavioral-educational program, met with their assigned peer twice weekly, and the parents completed social tasks with their children over a 7 month period. | 0.12 (−0.23, 0.47) | Individual | NON-TECH | 7–11 yrs; mean= 9 | 5% | 16 item Asher Loneliness Scale. |

| (Collins & Benedict, 2006) | Using newsletters and promotional flyers, participants were recruited from senior centers and senior housing developments in Las Vegas and rural Clark County Virginia. N=339. | Social support: Small-group class led by paraprofessionals, volunteer peer educators, and on-site staff. Topics included nutrition and food, personal safety, reducing accidents in the home, financial strategies to manage limited resources, general wellness, and productive aging. Class met weekly for 4 months. | −0.45 (−0.54, −0.36) | Group | NON-TECH | 52–93 yrs; mean= 73 | 80% | 4 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (de Vries et al., 1997) | Eligibility required a histologically-confirmed diagnosis of malignant neoplasm, measurable disease with documented progression prior to protocol therapy, no options for further medical treatment, an acceptable clinical condition (Karnofsky at least 80), and no concomitant somatic disease which might influence length of survival and physical or psychosocial functioning. N=35. | Social support: Patients were offered 12 sessions of individual psychosocial counseling once a week, each session lasting 1.5 to 2 hours. Patients also participated in fortnightly group meetings. These group sessions were guided by two psychotherapists and lasted 2.5 hours. Partners of the patients were also invited to participate in the individual and group sessions. | −0.14 (−0.46, 0.18) | Group | NON-TECH | 27–73 yrs; mean= 55 | 54% | 11 item De Jong Gierveld loneliness questionnaire. |

| (Kraut et al., 1998) | 1995 cohort comprised of families with teenagers participating in journalism classes in four Pittsburgh high schools. 1996 cohort comprised of families in which an adult was on the Board of Directors of one of four community development organizations. Households with active Internet connections were excluded and children younger than 10 years of age were excluded. N=169. | Social access: Families received a personal computer and software, a free telephone line, and free access to the Internet. Program lasted 2 years for the 1995 cohort and 1 year for the 1996 cohort. | −0.14 (−0.26, −0.02) | Individual | TECH | Not reported | 56% | 3 items from the UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Marshall, Bryce, Hudson, Ward, & Moth, 1996) | Non-familial male child molesters incarcerated in a medium security Canadian penitentiary participated in the study. They had volunteered for treatment in the Bath Institution Sex Offenders’ Program, a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral program. N=32. | Social cognitive training: Topics discussed in group meetings were benefits of being in a relationship, sexual relations, jealousy, development of relationship skills, and dealing with loneliness. This curriculum was part of an overall treatment package offered as a group therapy program. Duration of program not described. | −1.46 (−1.91, −1.01) | Group | NON-TECH | 24–53 yrs; mean= 37 | 0% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (McAuley et al., 2000) | Sedentary, older, U.S. community-dwelling adults were recruited using fliers, advertisements in the local newspapers and announcements on local radio shows and local television news programs. N=174. | Social access: Aerobic intervention group classes were conducted by trained exercise specialists and employed brisk walking for up to 40 minutes 3 times per week for 6 months. Stretching and toning intervention group exercised under supervision for 40 minutes 3 times per week for 6 months. | −0.08 (−0.25, 0.08) | Group | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean=67 | 72% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Petryshen, Hawkins, & Fronchak, 2001) | Community-dwelling adults who were socially isolated and living with a serious and persistent mental health problem and were eligible for a social recreation program within a Canadian community mental health center. N=36. | Social access: Social recreation intervention, which included information sessions about opportunities and resources in the community, workshops on relationship development, workshops on healthy lifestyles, self-help groups, weekly community walks, and community forums on mental illness. Approximately 200 group activities were offered per year. Participation varied considerably. The median number of activities completed by participants was 18. | −0.59 (−0.88, −0.30) | Group | NON-TECH | 18–65 yrs; mean=43 | 61% | 4 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Sorenson, 2003) | Women who reported significant psychological disruption after a traumatizing provider interaction during a birth experience unrelated to the baby’s physical outcome. Sample was recruited in conjunction with an International Cesarean Awareness Network (ICAN) state affiliate, ICAN referral agencies and midwifery practices in a U.S. metropolitan area. N=9. | Social cognitive training: 5 monthly group cognitive behavioral therapy sessions, each lasting 4 hours. Group leader was a psychiatric mental health clinical nurse specialist who encouraged the development of positive interpersonal relationships and provided support to confront issues and develop new cognitive and relationship skills. | −4.81 (−7.09, −2.53) | Group | NON-TECH | 26–45 yrs; mean=33 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Stewart, Craig, MacPherson, & Alexander, 2001) | Canadian widows over age 55 with no neurological deficits who spoke and wrote English and who were not currently attending a bereavement self-help or support group. N=23. | Social support: Four support groups comprised of 5–9 participants met for 1–1.5 hours weekly for a maximum of 20 weeks. Each group was led by a peer (widow) and a professional facilitator. Participants were invited to discuss their priority needs and relevant issues. Discussions were augmented by guest lecturers, case studies, audiovisual aids, and role-playing exercises. | −0.27 (−0.60, 0.06) | Group | NON-TECH | 54–77 yrs; mean=66 | 100% | 15 item Emotional/Social Loneliness Inventory. |

| (Stewart, Reutter, Letourneau, & Makawarimba, 2009) | Homeless youths in Edmonton were referred from employment programs, drop-in centers, and a Community Advisory Committee. N=14. | Social support: 20 week intervention program consisting of 4 support groups, which included one-on-one support, group recreational activities, and meals. | −0.34 (−0.77, 0.08) | Group | NON-TECH | 16–24 yrs; mean=19 | 46% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Yarnoz, Plazaola, & Etxeberria, 2008) | Long-term separated or divorced adults with children. N=7. | Social support: Attachment-based intervention, encouraging people to elaborate, through shared narratives with peers and the therapists, a representation of the events, the self, the other, and the relationships that contribute to a better adjustment to the situation of divorce. Participants met for a two-hour session each week for 8 months. Each session was led by a psychoanalyst and an attachment-oriented professional on an alternating basis. | −0.09 (−0.66, 0.49) | Group | NON-TECH | 50–60 yrs; mean=54 | 43% | 15 item Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale. |

TABLE 3.

Randomized Group Comparison Studies (N = 20)

| Authors | Enrollment Eligibility and Sample Size | Intervention Type and Duration | Effect Size (95% CI) | Intervention format | Intervention mode | Sample age | Sample % female | Loneliness Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Banks & Banks, 2002) | Recruited from three nursing homes in a city in southern Mississippi. Inclusion criteria included no cognitive impairment, no history of psychiatric disorder, and a score of 30 or greater on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. N=45. | Social support: Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) consisted of an attendant bringing a leashed dog to the participant’s room for 30 minutes. Participants were allowed to hold, stroke, groom, talk to, play with, or walk the dog in the hallway. Interaction with attendant was minimized. AAT-1 group members had one session per week while AAT-3 members had three sessions per week. Control group received no AAT sessions. Duration of study was 6 weeks. | −0.20 (−0.92, 0.52) | Individual | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean inferred=78 | 80% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Banks, Willoughby, & Banks, 2008) | Recruited from three nursing homes in St. Louis, Missouri. Inclusion criteria included no cognitive impairment, no history of psychiatric disorder, and a score of 30 or greater on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. N=26. | Social support: Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) consisted of a weekly 30 minute visit from either a living dog or a robot dog (AIBO) for 8 weeks. Sessions occurred in the resident’s room and consisted of the resident sitting in his or her chair or upright in bed with the dog or AIBO next to the resident. Control group received no AAT sessions. | −0.88 (−1.68, −0.07) | Individual | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean inferred=75 | Inferred as 80% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Chiang et al., 2009) | Participants were recruited from a nursing home in the Taipei area. Inclusion criteria were 1) conscious and able to speak Mandarin or Taiwanese, 2) aged 65 years or over, and 3) scored greater than 20 on the Mini Mental State Examination. N=92. | Social cognitive training: Intervention consisted of 8 weekly sessions of individual reminiscence therapy. Each session focused on a different topic, including sharing memories and greeting each other, increasing participant awareness of their feelings and helping them to express their feelings, and identifying positive relationships from their past and how to apply positive aspects of past relationships to present relationships. | −0.97 (−1.40, −0.54) | Individual | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean=77 | 0% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Christian & D’Auria, 2006) | Recruited from four university-based cystic fibrosis centers in North Carolina. N=116. | Social skills training: Educational problem-solving and social skills intervention designed to help children with cystic fibrosis (CF) deal with specific problems, including finding out about their CF diagnosis, explaining their CF related differences, dealing with teasing about CF, and keeping up with peers during physical activity. Intervention included an individual home visit and a structured, small-group (4 children) session approximately two weeks later. Control group did not receive intervention. | −0.08 (−0.44, 0.29) | Group | NON-TECH | 8–12 yrs; mean=9 | 49% | 16 item Asher Loneliness Scale. |

| (Coleman et al., 2005) | Women referred from hospitals in urban and rural communities in Arkansas and from the Arkansas Division of the American Cancer Society who were English-speaking and diagnosed with TNM stage 0, I, II, or III non-metastatic breast cancer, had no major underlying medical problems or previous history of cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancer) and who entered the study two to four weeks post-surgery. N=106. | Social support: In Phase I, oncology nurses provided weekly telephone social support from 2–3 weeks post-surgery through 3 months. In Phase II, weekly calls were continued through 5 months post-surgery and participants received a resource kit regarding adaptation to disease and treatment. In Phase III, calls were decreased to twice per month through 8 months post-surgery. In Phase IV, calls decreased to once per month until the one year anniversary of diagnosis. Control group received the same resource kit but no telephone social support. | −0.29 (−0.67, 0.09) | Individual | TECH | Range not reported: mean=57 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Conoley & Garber, 1985) | U.S. undergraduate students who scored one SD above the mean on UCLA Loneliness Scale and scored as moderately depressed on the Beck Depression Inventory. N=38. | Social cognitive training: Two 30-minute individual counseling sessions (1 week apart) which emphasized either reframing perception of loneliness or self-control (i.e., trying harder to overcome loneliness). Control group did not receive counseling sessions. | −0.32 (−0.96, 0.32) | Individual | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean inferred=20 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Cox, Green, Hobart, Jang, & Seo, 2007) | Community-dwelling older adults from the Denver area who were 55 years or older and required a minimum of 6 hours of personal care per week due to stroke, heart disease, osteoporosis, mild dementia, cancer, or severe arthritis. N=92. | Social support: 10 biweekly sessions of 1.5 to 2 hours related to specific themes and 2 review sessions. The goal was to increase the capacity of elderly care receivers to effectively manage their own care, including optimizing the relationship with their caregiver. Comparison group received needs assessment, referral and assistance, monthly follow-up and ongoing telephone assistance at the request of the participant. | −0.19 (−0.60, 0.22) | Individual | NON-TECH | 51–96 yrs; mean=79 | 77% | Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale on Lonely Dissatisfaction. |

| (Fukui, Koike, Ooba, & Uchitomi, 2003) | Recruited from a group of outpatients with breast cancer who were surgically treated at a national cancer center hospital in Japan. All patients were younger than 65 years old, had surgery within the previous 4–18 months, and had no chemotherapy or had completed chemotherapy. N=46. | Social support: 3 intervention groups of 6–10 patients met for 1.5 hours weekly for six weeks. Intervention consisted of health education, coping skills training, stress management, and psychological support. Goals of the intervention were to provide within-group support by professionals and peers, lessen the psychological distress associated with having cancer, and assist patients in learning effective coping methods for cancer related concerns. Control group did not receive intervention. | 0.15 (−0.43, 0.73) | Group | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean=54 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Heckman & Barcikowski, 2006) | Eligibility criteria included 50 years of age or older, HIV infected or had AIDS by self report, diagnosed with major depressive disorder, partial remission of major depression, dysthymia, or minor depressive disorder, and score of 75 or higher on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination. N=90. | Social support: Twelve weekly 90 minute telephone conference calls emphasizing coping strategies to reduce psychological distress. Each group was comprised of 6–8 participants and 2 leaders. Topics included sharing personal histories, identifying life stressors, sharing personal coping strategies, a discussion of adaptive problem-focused coping, adaptive emotion focused coping, and ways to increase social resources. Intervention duration was 3 months. Control group did not participate in conference calls. | 0 (−0.41, 0.41) | Group | TECH | Range not reported; mean=54 | 32% | 10 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Heller, Thompson, Trueba, Hogg, & Vlachos-Weber, 1991) | Telephone calls were made to a random sample of residences in low-income housing tracts in three Indiana communities to identify women living alone or with one other person in the household. Selection criteria were annual household income below median for Indiana senior citizens and either below median perceived support or above median loneliness. N=102. | Social support: Initial randomization was to either 10 weeks of friendly staff telephone contact or control group. Staff called twice a week for 5 weeks then once a week for 5 weeks. Staff inquired about participant’s health and well-being, events of the week, and stressful life events. After 10 weeks, those receiving the staff contact were randomly assigned to continue that contact or were paired in dyads to continue phone contact with one another. Control group received no intervention. | −0.12 (−0.51, 0.27) | Individual | TECH | Range not reported; median=74 | 100% | 7 item Paloutzian and Ellison Loneliness Scale. |

| (Hill, Weinert, & Cudney, 2006) | Community-living, chronically ill women living in rural western U.S. Recruitment occurred through mass media, agency and service organization newsletters, and word of mouth. N=100. | Social access: 22 weeks of participation in an online, asynchronous, peer-led support group, and a health teaching unit. Participants received in-home Internet access to e-mail and an asynchronous chat room in which they exchanged feelings, expressed concerns, provided support, and shared life experiences. Intervention also included web-based health education modules. In addition, participants also engaged in expert-facilitated chat room discussions related to the health teaching unit activities. Control group did not receive intervention. | 0.004 (−0.39, 0.40) | Group | TECH | 35–65 yrs; mean inferred=52 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Jessen, Cardiello, & Baun, 1996) | Men and women ages 65 or older admitted to two Midwestern skilled rehabilitation units. All newly admitted persons were approached but participation was voluntary. N=40. | Social support: Caged bird (budgerigar) placed in participant’s room for 10 days. Participants received verbal and written instructions regarding the bird but participants did not provide care to the bird. Control group did not receive the intervention. | 0.40 (−0.23, 1.02) | Individual | NON-TECH | 65–91 yrs; mean=76 | 68% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Kremers, Steverink, Albersnagel, & Slaets, 2006) | Participants recruited through advertisement in local newspapers in two regions of the Netherlands. Single, community-dwelling women, 55 years and older, were asked by phone if they missed having people around them, wished to have more friends, participated in very few leisure activities, or had trouble initiating activities. N=119. | Social skills training: Intervention consisted of six weekly group meetings which included 8–12 participants and two facilitators. Each meeting lasted 2.5 hours and focused on one or more techniques, including taking initiative in making friends, investing in friendships, having a positive frame of mind, finding and maintaining multifunctionality in friendship, and having more than one friend. Control group did not participate in group meetings. | 0.12 (−0.25, 0.49) | Group | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean=64 | 100% | 11 item De Jong Gierveld loneliness questionnaire. |

| (McWhirter & Horan, 1996) | U.S. university students who responded to a publicized program at a university counseling center were accepted if they scored one standard deviation above the mean on the UCLA Loneliness Scale for college age populations, reported experiencing loneliness within the four week period prior to intake, and presented no clinical evidence of suicidal behavior or severe depression. N=22. | Social cognitive training: A counselor led each structured, small group (3–5 participants) experience, which met for two hours each week for 6 weeks. Intimate condition group used cognitive and behavioral techniques to focus on establishing and maintaining intimate relationships. Social condition group combined cognitive restructuring with modeling, role play, and homework assignments for developing better communication skills in social settings. Combined condition group included all elements of the intimate and social condition groups. Control condition met to express feelings and share experiences but counselor did not suggest ways to reduce loneliness. | −0.89 (−1.77, −0.01) | Group | NON-TECH | 18–38 yrs; mean=25 | 48% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale from which intimate and social loneliness subscales were derived. |

| (Morrow-Howell, Becker-Kemppainen, & Lee, 1998) | Older U.S. adults in the St. Louis area who either called a suicide crisis hotline or were referred from family members, friends, or professionals due to depression, social isolation, or unmet needs in activities of daily living. N=61. | Social support: Social worker made weekly telephone calls to administer three components of the program: multidimensional psychosocial evaluation, assistance with social services, and supportive therapy, through which the social worker encouraged the client to articulate problems, explore possible solutions, and take action. Median length of contact was 8 months. Control group did not receive intervention. | −0.09 (−0.59, 0.41) | Individual | TECH | 61–92 yrs; mean=76 | 85% | OARS Social Resource Rating Scale regarding loneliness frequency. |

| (Ollonqvist et al., 2008) | Working in collaboration with seven independent rehabilitation centers and 41 municipalities throughout Finland, the goal was to recruit a representative sample of frail older persons over age 65 who were living at home but faced a risk of institutionalization within two years due to progressively decreasing functional capacity. N=644. | Social support: Intervention consisted of a network-based group rehabilitation program which consisted of three separate inpatient periods at a rehabilitation center within eight months. Participants had individual visits with the physician, physiotherapist, social worker, and occupational therapist. In addition, participants engaged in group activities which focused on various exercises, as well as group discussions and lectures. Topics included promotion of self-care, psychological counseling, medical issues, social services, and recreational activities. | −0.17 (−0.33, −0.02) | Group | NON-TECH | 65–96 yrs; mean=78 | 86% | Do you feel yourself lonely? 0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always. |

| (Samarel, Tulman, & Fawcett, 2002) | English-speaking U.S. women who had had surgery for non-metastatic (TNM stage 0, I, II, or III) breast cancer within 4 weeks prior to study participation, had no previous cancer diagnosis except for non-melanoma skin cancer, and had no other major medical problems. N=82. | Social support: Experimental group received weekly 2-hour, group social support and education (topics included stress management, communication techniques, problem solving skills, and understanding emotions and needs) as well as weekly individual telephone social support and education over 13 months. Control group 1 received weekly individual telephone social support and education over 13 months. Social support and education were provided by either oncology nurse-clinicians or social workers. Control group 2 received educational resource kit via a one-time mailing. | −0.51 (−0.97, −0.05) | Group | TECH | 30–83 yrs; mean=54 | 100% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Savelkoul, de Witte, Candel, Van Der Tempel, & Van Den Borne, 2001) | Patients of rheumatology clinics in 2 regional hospitals in the Netherlands. Final sample was selected on the basis of chronic rheumatologic condition, duration of more than 1 year, age between 35 and 65 years, higher than median score on impact of rheumatic disease on functional health status, and a higher than median score on at least 1 of the following: loneliness, lack of social support, or impact of rheumatic disease on social behavior. N=75. | Social support: Aim of coping intervention group was to increase action-oriented directed coping and coping by seeking social support. Emphasized 4 steps: describe the problem, think about possible solutions, choose 1 or more solutions, implement the solution and evaluate the results. Aim of mutual support group was to exchange information, experiences, feelings, and emotions. No coping skills were taught. There were 10 weekly two-hour sessions in each intervention and each group was comprised of 10–12 participants. Control group did not receive the intervention. | −0.04 (−0.49, 0.41) | Group | NON-TECH | 35–65 yrs; mean=51 | 68% | 11 item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness questionnaire. |

| (White et al., 2002) | Residents of four U.S. congregate housing sites and two nursing facilities. Volunteers were solicited during information sessions open to all residents at each site. N=93. | Social access: 9 hours of training over a two week-period. Training covered basic computer operation, use of e-mail, and introduction to accessing the Internet. Each participant also received a training manual. Subsequently, the trainer was available at each site for about two hours per week for technical support. Trainer was also available by phone and e-mail. Duration of program was 5 months. Control group did not receive the intervention. | −0.13 (−0.54, 0.27) | Individual | TECH | Range not reported; mean=71 | 76% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

| (Williams et al., 2004) | Recruits at basic training at the Naval Recruit Training Command at Great Lakes, Illinois. Those who scored 18 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory of 30 or higher on the Perceived Stress Scale were classified as at-risk recruits. N=200. | Social cognitive training: Cognitive behavioral intervention consisted of 10–15 at-risk recruits meeting for 45 minutes each week for 9 weeks. Groups were facilitated by a psychologist. Participants read a manual each week, then discussed and practiced strategies for coping, increasing one’s sense of belonging, decreasing thought distortion, and stress management. Non-intervention and comparison groups participated in weekly meetings which focused on other topics, such as swimming skills and personal hygiene. | −0.36 (−0.64, −0.08) | Group | NON-TECH | Range not reported; mean=20 | 28% | 20 item UCLA Loneliness Scale. |

Effect Size Calculation

Established procedures were used to calculate the effect size for each of the qualified studies (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). The standard error of each effect size was calculated in order to derive the inverse variance that served as our weighting unit for the mean effect size across studies. For a better depiction of the relative weight given to each study, the percentage of weight was calculated by dividing each individual weight by the sum of weights from each group of studies.

For single group pre-post studies, effect sizes were calculated by taking the difference between pre- and post-treatment loneliness scores and dividing by the pooled standard deviation of the two scores. Correlations between pre- and post-treatment loneliness values were required to calculate standard errors of the pre-post effect sizes using the formula:

where SE = standard error of the effect size, r = the correlation between pre- and post-treatment loneliness values, n = the sample size, and ES = effect size. With two exceptions (Christian & D’Auria, 2006; Cox, Green, Hobart, Jang, & Seo, 2007), these correlations were not provided by study authors. These correlations were estimated to be 0.7, which approximates the test-retest reliability for loneliness over periods of a year or more, and is consistent with test-retest correlations reported in the literature (Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006; Russell, 1996).

For randomized and non-randomized group comparison studies, effect sizes were calculated as the loneliness difference between the treatment and control group divided by the pooled standard deviation of the two scores. Standard errors of the effect sizes were calculated by multiplying the pooled standard deviation with the square root of the sum of the inverse of each sample size.

If a study didn’t provide enough information regarding the means and standard deviations of the post-treatment loneliness scores but provided chi-square, F, or t test results on the difference between the treatment and control group after the intervention, an online effect size calculator was accessed to determine the effect sizes from those test results (Wilson, 2002).7

When the authors reported the effect sizes but not other statistics for their intervention (Banks & Banks, 2002; Savelkoul, de Witte, Candel, Van Der Tempel, & Van Den Borne, 2001), those effect sizes were used.8 If the author reported subscale loneliness scores separately (McWhirter & Horan, 1996; Stewart, Craig, MacPherson, & Alexander, 2001), effect sizes were calculated for all sub-scales and their mean was reported as the effect size for the given study.

Effect sizes based on post-treatment group differences and their pooled standard deviations are known as Cohen’s g, which is said to be upwardly biased especially for small samples (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). To adjust for this bias, g was multiplied by a correction term of [1 – 3/(4N-9)] where N equals the sample size to get an unbiased estimator known as Hedge’s d (Hedges & Olkin, 1985), and this adjusted effect size was used for our analyses.

Studies were evaluated for baseline differences in loneliness between the treatment and control groups, especially studies with non-randomized group comparison designs. Four of the studies reported baseline differences in loneliness between the treatment and control groups: (Cohen et al., 2006; Hartke & King, 2003; Martina & Stevens, 2006; White et al., 1999). To avoid misleading effect sizes that would result from comparing only the post-treatment scores, the effect size was calculated as the difference between the changes of the treatment and the control groups. In addition, in one study (Kolko, Loar, & Sturnick, 1990), baseline differences in loneliness were not reported but were determined to be present because confidence intervals around treatment and control group loneliness means at baseline did not overlap. These groups were treated as statistically different at baseline and effect size was calculated accordingly.

Primary Effect Size

Effect sizes included in Tables 1–3 are “primary” effect sizes, which were calculated from the first available post-treatment measurement time point. In addition, in studies with more than one intervention group, the primary effect size was calculated for the intervention group that reflected the key feature of each intervention, or that incorporated the fewest design flaws. In studies with more than one control group, the control group that was theoretically expected to exhibit the greatest difference from the treatment group was used to calculate the primary effect size.

Five studies had more than one intervention group. For three of these studies, the primary effect size was based on the intervention that best represented the key features of the intervention. In Allen-Kosal (2008), the three intervention groups received, respectively, a pre-training session, an eight-week class, or both a pre-training session and a class. The group with both the pre-training and the eight-week class was selected to calculate the primary effect size. In Banks et al. (2008), animal-assisted therapy was provided to one intervention group with a robotic dog, and to a second group with a real dog. A sizeable literature documents the benefits of owning “real” pets (Keil, 1988), so the real dog intervention was included as the primary intervention. In McWhirter & Horan (1996), the three intervention groups—intimate condition, social condition, and combined condition—focused on a different set of skills and techniques for improving intimate, social, or both types of relationships, respectively. The combined condition included both the intimate and social components of the intervention and was therefore treated as the primary effect.

In two additional studies with more than one intervention group, the intervention with the fewest implementation failures was selected to calculate the primary effect size. In Cox et al. (2007), a small group-based version and an individual-based version of the “Care-Receiver Efficacy Intervention” were compared with a standard individual-based case management group. Randomization wasn’t fully implemented because only participants who were able to access and participate in the group-based intervention were eligible for the small-group treatment, and all eligible participants were assigned to the small-group treatment. All individual-eligible participants were randomly assigned to individual-based treatment or the case management control group condition. The effect size from the individual intervention group was therefore treated as the primary intervention. In Heller et al. (1991), the effect on loneliness and psychological well-being of telephone call support from staff was compared to that of telephone support from peers. Participants were first randomized into treatment or control groups. The treatment group received 10 weekly staff phone calls whereas the control group received no intervention. After 10 weeks of regular staff phone calls, participants in the treatment group were randomly assigned to one of three intervention conditions. In one intervention, staff phone calls continued. In the second and third intervention types, participants were assigned to either receive or initiate regular phone calls with a peer in the study. The frequency of phone calls was held constant across all intervention types. However, since 27 out of the 125 participants (22%) in the second and third intervention groups declined to participate after the randomization and all of the participants in the staff contact group remained, the staff contact group was used to calculate the primary effect size to avoid the potential self-selection problem in the other two groups. The control group used for the calculation of the primary effect size was the group that received nothing throughout the study.

Three studies included more than one control group. In Samarel et al. (2002), the treatment included telephone support and group social support along with a mailed education kit; one control group received telephone support with mailed materials, and the other control group received only the mailed materials. The primary effect size was calculated using the control group that received the mailed materials only (i.e., the group that was expected to exhibit the greatest difference relative to the treatment group). Conoley & Garber (1985) administered cognitive reframing as the main intervention. In addition to the control group that received no intervention, this study had another comparison group whose members were instructed “to try harder” to overcome loneliness. The primary effect size was calculated using the control group that received no intervention. Heckman & Barcikowski (2006) had two time-lagged intervention groups (immediate and delayed) serving as control groups for each other; effect sizes were calculated for both interventions but the immediate condition was treated as the primary intervention because its control group didn’t receive any intervention and thus was more comparable to the control groups of other included studies.

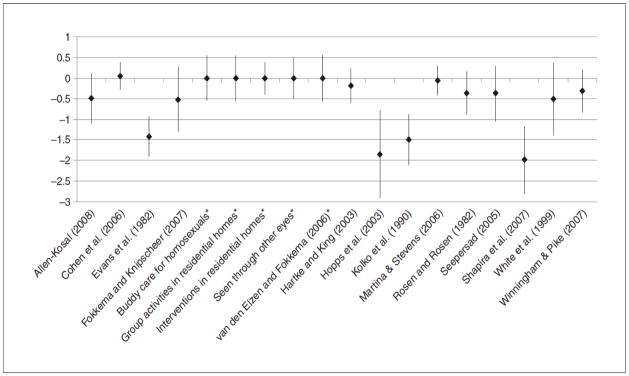

Analyses