Abstract

Nucleoporin Nup98 is a component of the nuclear pore complex, and is important in transport across the nuclear pore. Many studies implicate nucleoporin in cancer progression, but no direct mechanistic studies of its effect in cancer have been reported. We show here that Nup98 specifically regulates nucleus–cytoplasm transport of galectin-3, which is a β-galactoside-binding protein that affects adhesion, migration, and cancer progression, and controls cell growth through the β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer cells. Nup98 interacted with galectin-3 on the nuclear membrane, and promoted galectin-3 cytoplasmic translocation whereas other nucleoporins did not show these functions. Inversely, silencing of Nup98 expression by siRNA technique localized galectin-3 to the nucleus and retarded cell growth, which was rescued by Nup98 transfection. In addition, Nup98 RNA interference significantly suppressed downstream mRNA expression in the β-catenin pathway, such as cyclin D1 and FRA-1, while nuclear galectin-3 binds to β-catenin to inhibit transcriptional activity. Reduced expression of β-catenin target genes is consistent with the Nup98 reduction and the galectin-3–nucleus translocation rate. Overall, the results show Nup98’s involvement in nuclear–cytoplasm translocation of galectin-3 and β-catenin signaling pathway in regulating cell proliferation, and the results depicted here suggest a novel therapeutic target/modality for cancers.

Keywords: Nucleoporin, Nuclear pore complex, Galectin-3, Nuclear transport, Cancer progression

1. Introduction

Cancer development and progression is a complex process that involves functional and genetic abnormalities, which lead to altered gene expression and overall cell function. Recently some nucleoporins have been linked to cancers [1,2]. Nucleoporins are the main components of the nuclear pore complex (NPC), which bridge the nuclear envelope to form a transport channel between the nucleus and the cytoplasm [3]. Several cellular processes, including molecular nucleocytoplasmic transport, are controlled by nucleoporins. Interestingly, several nucleoporins were linked to cancer; Nup88 was found to be overexpressed in ovarian, breast, colorectal cancer, etc. [4]. Rae1 expression was abberant in breast cancer [5], and Nup98 and translocated promoter region (Tpr) were observed as chimeric fusion proteins by chromosomal translocations in leukemia, gastric, and thyroid cancer [6,7]. Although nucleoporins have been the objects of much investigation, very little is known of their function in cancer progression.

A key factor in cancer progression is galectin-3—a member of an evolutionary conserved family of β-galactoside-binding proteins, which is ubiquitously expressed and involved in diverse biological functions [8]. Galectin-3 plays several significant roles in cancer progression, involving cell growth, adhesion, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and apoptosis [9]. Interestingly, galectin-3 shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus and its nuclear import involves karyopherins (importins) [10]. Galectin-3’s localization in two cellular compartments is associated with cancer progression; reportedly, cytoplasmic galectin-3 promotes tumor progression, whereas nuclear galectin-3 suppresses malignancy [11]. Galectin-3 expression in the nucleus is greatly decreased in colon and prostate cancer; marked reduction of nuclear galectin-3 was seen in tongue cancer progression [12,13]. Cytoplasmic galectin-3 expression translocated from the nucleus also exhibits anti-apoptotic activity [14]. Galectin-3 localization in the nucleus or cytoplasm is critical for cancer progression, although the mechanism of translocation is yet to be determined.

Karyopherins mediate nuclear protein transport in association with nuclear pore complex proteins—mainly, the nucleoporin Nup98 [15]. Thus, here we examined the mechanism of galectin-3 translocation regulation by Nup98 and established critical roles for Nup98 and galectin-3 in cancer progression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and antibodies

Anti-Nup98 antibody was kindly donated from Dr. Günter Blobel (Rockefeller University). Anti-galectin-3 antibody was described elsewhere [14]. Anti-α-tubulin and Nup62 antibodies were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-Nup88 and β-catenin antibodies were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Anti-Nup358 and CRM1 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Nup214 and Nup153 antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-GFP antibody was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Casein kinase 1 (CK1) inhibitor D4476 was purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI).

2.2. Cell culture

Human cervical cancer cell line HeLa and human breast cancer cell line MCF7 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Human breast cancer cell lines BT-549 and MDA-MB-231 were kindly provided by Dr. Erik W. Thompson (University of Melbourne). The establishment of stable BT-549-galectin-3 clones was described previously [14]. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

2.3. Transfections

The plasmid encoding full-length human Nup98 tagged with GFP was described previously [16,17]. The Nup981–505 domain (Nup98-N) and the Nup98506–920 domain (Nup98-C) were sub-cloned by PCR into the pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). The full-length Nup62 coding region was PCR-amplified from cDNA and subcloned into pEGFP-C1 vector. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All cloning procedures were essentially carried out as described previously [17]. Cells were transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). siRNA duplexes targeting Nup98 (sc-43535), Nup62 (sc-36107), and control siRNA (sc-37007) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. siRNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Equal amounts of the proteins were separated on SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to 0.2 μm polyvinylidene fluoride membrane at 15 V, 30 mA overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibody and secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence system.

2.5. Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were pre-cleared and then mixed together with protein A/G bead slurry (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) adding various antibodies as specified, and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with rocking. The beads were then washed five times with lysis buffer. After extensive washing with lysis buffer, proteins were eluted with SDS–PAGE blue loading buffer, followed by boiling, and subjected to immunoblotting.

2.6. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). The cDNA for PCR template was generated by using ThermoScript™ RT-PCR System for First-Strand cDNA Synthesis (Invitrogen). Each PCR cycle consisted of: 1 min at 95 °C, 1 min at 55 °C and 2 min at 72 °C for cyclin D1, FRA-1 and GAPDH. PCR-amplified products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The primer sets were as follows: for cyclin D1, forward: 5′-AACTACCTGGACCGCTTCCT-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCACTTGAGCTT GTTCACCA-3′; for FRA-1, forward: 5′-AGCTGCAGAAGCAGAAG-GAG-3′ and reverse: 5′-GGAGTTAGGGAGGGTGTGGT-3′; for GAPDH, forward: 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′ and reverse: 5′-TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG-3′. Each expression was standardized using GAPDH as an internal control. Density of each band was quantitated with ImageJ software.

2.7. Immunofluorescence

Cells seeded on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed thrice with PBS and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. The cells were blocked with 4.0% BSA in PBS for 30 min and then labeled with primary antibody for overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, the cells were washed with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorophores for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After washing with PBS, samples were mounted onto coverslips with Pro-Long Gold Antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and were examined on a Zeiss LSM5 EXCITER confocal microscope, and all images were acquired using an aplan-Apochromat 63× or 100× with a 1.4-N.A. objective.

2.8. Cell growth

Cell growth was determined by Trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Cells were plated into 12-well culture dishes. After incubation, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, centrifuged, and cell pellets were then resuspended in PBS. Cells were stained with trypan blue, and counted using a hematocytometer.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD for triplicate determinations. Comparisons between groups was determined using unpaired Student’s t tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Nup98 interacts with galectin-3

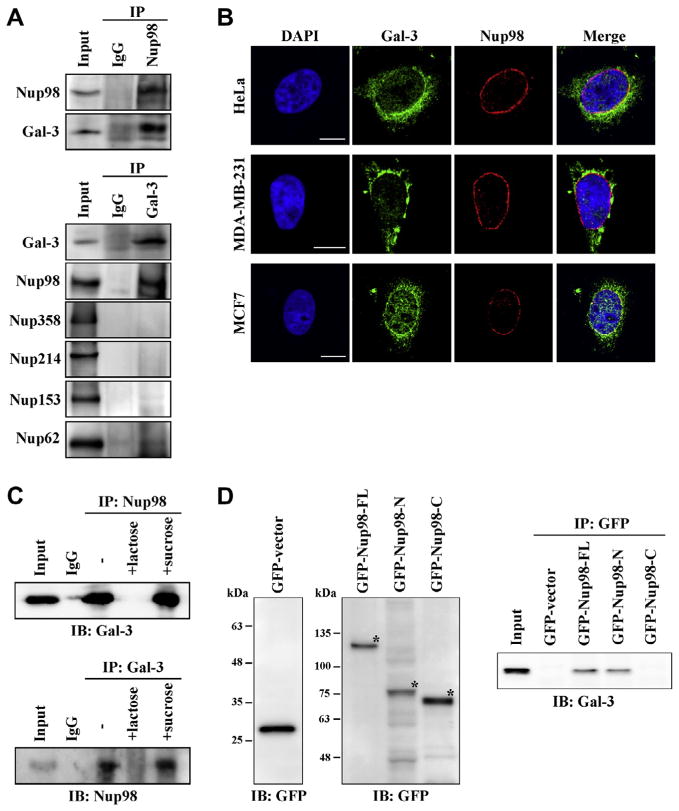

We have reported that galectin-3 is transported into the nucleus by karyopherins, and it has also been suggested that karyopherins bind to some nucleoporins, including Nup98 [10,15]. These findings prompted us to investigate a possible link between nucleoporins and galectin-3. To examine whether galectin-3 associated with nucleoporins in HeLa cells, we used immunoprecipitation assays to detect coprecipitating Nup98, along with galectin-3; conversely, we immunoprecipitated Nup98 using anti-galectin-3 antibodies (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the immunoprecipitation data, we found that Nup98 colocalized with galectin-3 on the nuclear membrane in HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 cells (Fig. 1B). We also found the Nup98 and galectin-3 complex was inhibited by 50 mM lactose treatment but not by 50 mM sucrose, suggesting the carbohydrate recognition binding domain of galectin-3 is important to this interaction (Fig. 1C). Reciprocally, the N-terminal domain of Nup98 (1–505aa) interacted with galectin-3 (Fig. 1D). Nup98 N-terminal contains Phe–Gly (FG) repeats, and Nup98 is thus a member of FG nucleoporins such as Nup62, Nup153, Nup214, and Nup358 [1–3]. Therefore we also checked other FG nucleoporins to interact with galectin-3, and found that no other FG nucleoporins could coprecipitate though Nup62 showed slight interaction (Fig. 1A). These data suggest that Nup98 specifically interacts with galectin-3.

Fig. 1.

Nup98 colocalizes with galectin-3. (A) HeLa cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nup98, -galectin-3, or nonspecific rabbit antibodies (IgG) followed by immunoblot analysis for Nup98, galectin-3 and FG nucleoporins expression. Cell lysates were also immunoblotted as a control (Input). IP, immunoprecipitation. (B) HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 cells were stained with anti-galectin-3 and anti-Nup98 antibodies for immunofluorescence visualization and examined by confocal microscopy. Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bars: 10 μm. (C) Cell lysates were treated with 50 mM lactose (+lactose) or sucrose (+sucrose), immunoprecipitated with anti-Nup98, -galectin-3, or IgG, and then analyzed via immunoblot for Nup98 and galectin-3 expression. IB: immunoblot. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with Nup98 (full-length) or Nup98 fragments (Nup98-N and Nup98-C) expression plasmid tagged with GFP. After 48 h, the cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-galectin-3 antibody. Asterisks indicate the GFP fusion proteins. FL: full-length.

3.2. Nup98 transports galectin-3 into cytoplasm

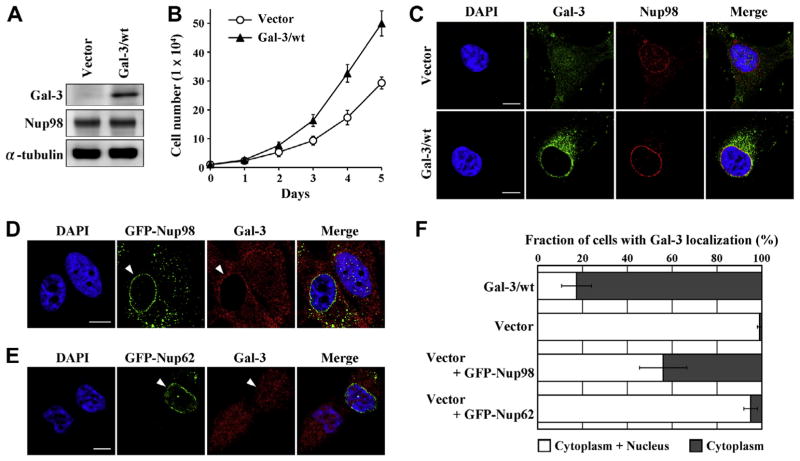

To study galectin-3 transportation by Nup98, BT-549 cells with vector control and wild-type galectin-3-overexpressing BT-549 cells (Vector and Gal-3/wt, respectively) were stably established. Galectin-3 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting. BT-549-galectin-3 cells expressed galectin-3 protein whereas vector cells did not express detectable levels of galectin-3 (Fig. 2A). Galectin-3-overexpressing clones grew faster than those of vector-transfected control cells (1.7-fold at 3 day, 1.9-fold at 4 day and 1.8-fold at 5 day; Fig. 2B). Immunocytochemistry showed BT-549-galectin-3 cells to have colocalized Nup98 and galectin-3—similar to HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 cells—whereas vector cells showed very little galectin-3 staining (Fig. 2C). Moreover, galectin-3 was found almost exclusively in the cytoplasm in BT-549-galectin-3 cells (Fig. 2C and F). To determine whether Nup98 regulated localization of galectin-3, we analyzed overexpression of GFP-Nup98 in BT-549 vector cells. BT-549 vector cells displayed galectin-3 staining dispersed throughout the cell although the cell contained low levels of galectin-3; also, Nup98 overexpression promoted galectin-3 cytoplasmic translocation (Fig. 2D and F), whereas Nup62 and Tpr overexpression did not (Fig. 2E and F and data not shown). These data indicate that Nup98 specifically regulates galectin-3 transportation from nucleus to cytoplasm.

Fig. 2.

Nup98 regulates galectin-3 export from nucleus. (A) BT-549 cells were stably transfected with plasmids containing galectin-3 cDNA (Gal-3/wt) or control plasmids (Vector). Cells were analyzed by immunoblot analysis for galectin-3 and Nup98 expression; α-tubulin expression is shown as loading control. (B) Cell growth was determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. BT-549-galectin-3 clones were seeded at low density and grown for 5 d. (C) Cells were stained with anti-galectin-3 and anti-Nup98 antibodies. Scale bars: 10 μm. (D) Representative images of BT-549-Vector cells transfected with plasmids overexpressing GFP-Nup98 (full-length). At 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed, stained with anti-galectin-3 antibody, and analyzed by confocal laser microscopy. White arrowhead: GFP-Nup98-transfected BT-549-Vector cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. (E) Representative images of BT-549-Vector cells transfected with plasmids overexpressing GFP-Nup62 (full-length). White arrowhead: GFP-Nup62-transfected BT-549-Vector cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. (F) Quantitation of subcellular localization of the galectin-3 proteins. Localization was classified as in cytoplasm or cytoplasm plus nucleus. Data are presented as percentage of cells in each location class (means ± S.D.) for triplicate determinations, counting ≥100 transfected cells in each experiment.

3.3. Nup98 depletion leads to nuclear localization of galectin-3 and retardation of cell growth

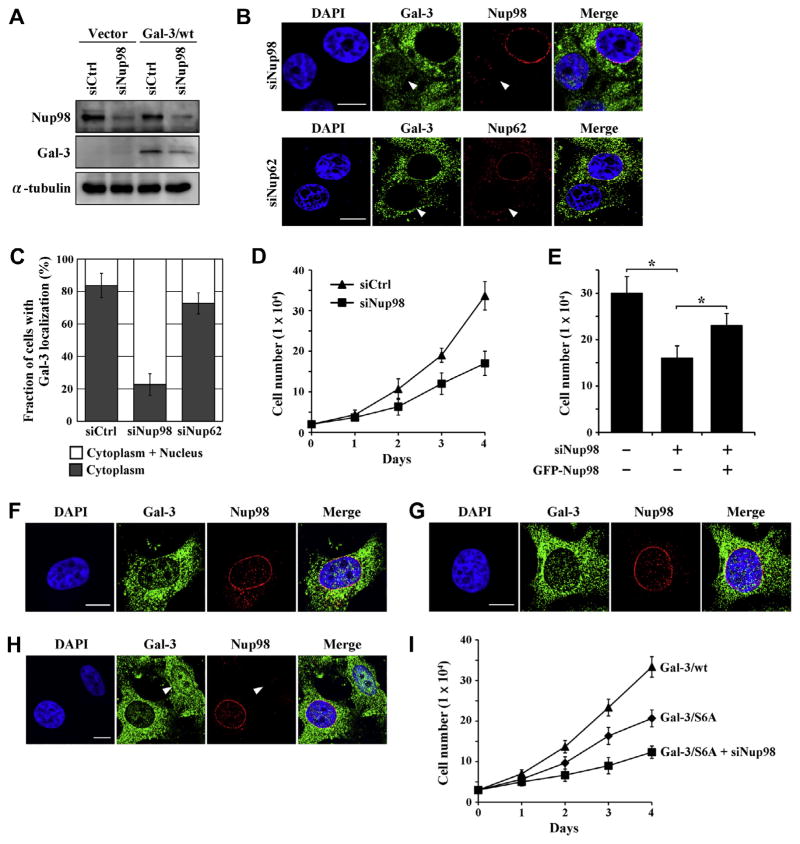

We next performed a Nup98 siRNA knockdown assay to investigate the effect of Nup98 on galectin-3 transportation. To verify silencing of Nup98, we detected protein expression levels in siRNA-transfected BT-549-galectin-3 clones (Fig. 3A). Immunoblot data showed that Nup98 was decreased in Nup98 siRNA-transfected cells, by approximately 90%, compared to control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 3A). Galectin-3 in BT-549-galectin-3 cells was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, whereas nuclear galectin-3 could be seen after Nup98 depletion (Fig. 3B and C). Nup62 and Tpr depletion did not affect galectin-3 localization (Fig. 3B and C and data not shown). We further investigated the effect of CRM1, which mediates export from the nucleus of numerous proteins, and no major changes were found in galectin-3 localization in CRM1-depleted cells (data not shown). These findings also suggest that Nup98 is important for exit of galectin-3 from the nucleus.

Fig. 3.

Nup98 depletion leads to nuclear translocation of galectin-3 and growth inhibition. (A) BT-549-galectin-3 clones transfected with control siRNA duplex (siCtrl) or Nup98 siRNA (siNup98) for 72 h were analyzed by immunoblot analysis for Nup98 and galectin-3 expression. (B) BT-549-galectin-3 cells were transfected with Nup98 (upper panel) or Nup62 (lower panel) siRNA for 72 h. Galectin-3, Nup98 and Nup62 were then visualized. White arrowhead: Nup98 or Nup62-depleted BT-549 cells. Scale bars: 10 μm. (C) Quantitation of subcellular localization of galectin-3 proteins. BT-549-galectin-3 cells were transfected with control, Nup98 or Nup62 siRNA for 72 h; cells from each indicated transfection condition were scored. Data are presented as in Fig. 2F. (D) Cell growth after Nup98-depletion was determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. BT-549-galectin-3 cells were transfected with control or Nup98 siRNA. (E) Numbers of BT-549-galectin-3 cells transfected with control, Nup98 siRNA, or Nup98 siRNA followed by GFP-Nup98 expression were analyzed. Cells were counted by a trypan blue dye exclusion assay on day 4. Bars: SD. *P < 0.05. (F) BT-549 cells were stably transfected with plasmid containing phosphomutant galectin-3 cDNA (Ser6 → Ala, Gal-3/S6A). Cells were stained with anti-galectin-3 and anti-Nup98 antibodies. Scale bar: 10 μm. (G) BT-549-galectin-3 cells were exposed to selective casein kinase 1 inhibitor D4476 (50 μM) for 48 h, and then were stained with anti-galectin-3 and anti-Nup98 antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (H) BT-549-phosphomutant-galectin-3 clone was transfected with Nup98 siRNA for 72 h, and then galectin-3 and Nup98 were visualized. White arrowhead: Nup98-depleted cell. Scale bar: 10 μm. (I) Cell growth after Nup98-depletion was determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. BT-549-galectin-3 clones (Gal-3/wt and /S6A) were transfected with control or Nup98 siRNA.

To investigate the effect of Nup98 knockdown on cell growth, a cell growth assay was performed. The results showed that knockdown of Nup98 slowed the cell proliferation rate, resulting in reduced cell numbers (0.63-fold at 3 day and 0.51-fold at 4 day; Fig. 3D. We further found that the retardation of cell growth by Nup98 depletion was partially rescued by transfection with GFP-Nup98 (Fig. 3E). These data show that Nup98 depletion followed by galectin-3 retention in the nucleus inhibits cell growth.

We further examined the effect of Ser 6 phosphorylation of galectin-3 on its translocation, as phosphorylation of galectin-3 is reportedly important for its nuclear export in normal mouse fibroblasts [18]. To study the role of galectin-3 phosphorylation in translocation, we used stable wild-type galectin-3 (Gal-3/wt) and Ser6 → Ala phosphomutant galectin-3 (Gal-3/S6A) transfectants [14]. As shown in Fig. 3F, Ser6 mutant galectin-3 was mostly located in the cytoplasm of cells, which displayed only a moderate level of nuclear staining. Since CK1 is reported to phosphorylate galectin-3 including Ser6, we tested the effect of the CK1 inhibitor D4476 on galectin-3 translocation. Similar to Fig. 3F, nuclear galectin-3 staining was obtained with D4476 treatment in BT-549-galectin-3 cells (Fig. 3G). Nup98-depleted cells in BT-549-Ser6 mutant galectin-3 clones also showed further increased nuclear galectin-3 (Fig. 3H). Growth assay revealed that BT-549-Ser6 mutant galectin-3 clones grow slower than wild type galectin-3 clones (0.69-fold at 3 day and 0.62-fold at 4 day); Nup98 depletion caused growth retardation in BT-549-Ser6 mutant galectin-3 cells (0.55-fold at 3 day and 0.59-fold at 4 day; Fig. 3I). These findings show Nup98 and also galectin-3 phosphorylation are critical for nuclear export of galectin-3, and also suggest that nuclear galectin-3 negatively regulates cell growth.

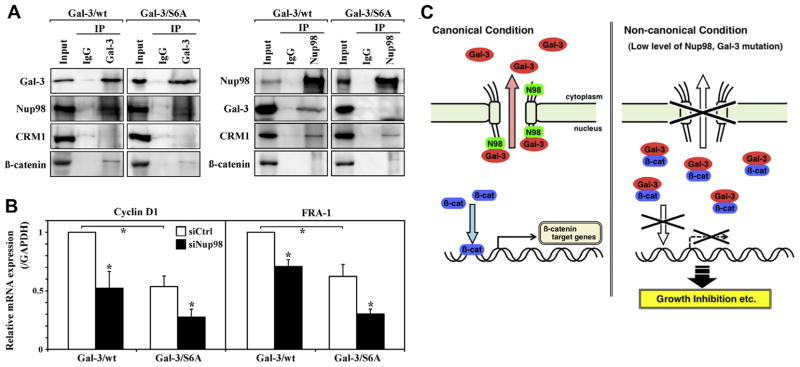

3.4. Involvement of Nup98 and galectin-3 in β-catenin pathway

The β-catenin signal pathway is required for development and is frequently activated in cancer. In the nucleus, β-catenin acts as a transcription factor and promotes expression of several target genes, such as cyclin D1. As galectin-3 can bind to β-catenin [19], we hypothesized that nuclear galectin-3 and Nup98, as a galectin-3’s regulator of translocation, could be involved in β-catenin pathway. Initially, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments in BT-549-galectin-3 cells. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-galectin-3 antibody, and β-catenin was detected as previously reported [19], but CRM1 was not detected (Fig. 4A). Conversely, Nup98 could immunoprecipitate CRM1 but not β-catenin (Fig. 4A). We further investigated using BT-549-Ser6 mutant galectin-3 clones, and found that Ser 6 mutant galectin-3 could still bind to β-catenin but lost the ability to bind to Nup98 (Fig. 4A). After Nup98 depletion, galectin-3 translocates to the nucleus and may colocalize with β-catenin in the nucleus. In addition, Nup98 siRNA retarded cell growth (Figs. 2B and 3I), suggesting nuclear galectin-3 binds to β-catenin to negatively regulate β-catenin pathway. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed β-catenin target gene expression after Nup98 knockdown, using semiquantitative RT-PCR. Nup98 knockdown reduced mRNA expression of β-catenin target genes, such as cyclin D1 and FRA-1, in BT549-galectin-3 clones (Fig. 4B). Our preliminary data in human colorectal cancer SW480 cells, which have mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) that renders β-catenin resistant to degradation, showed a similar observation on protein localization, cell growth and mRNA expressions (data not shown). Reduced mRNA expression rate is consistent with the galectin-3 translocation rate into the nucleus. Together, these data imply that Nup98 and galectin-3 are associated with β-catenin pathway, and nuclear galectin-3 negatively regulates the β-catenin pathway by disturbing β-catenin transcription.

Fig. 4.

Nup98-dependent galectin-3 nuclear translocation regulates β-catenin pathway. (A) BT-549-galectin-3 clones (Gal-3/wt and /S6A) lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-galectin-3, -Nup98, or IgG followed by immunoblot analysis for galectin-3, Nup98, CRM1 and β-catenin expression. (B) BT-549-galectin-3 clones (Gal-3/wt and / S6A) were transfected with control or Nup98 siRNA for 72 h; levels of cyclin D1 and FRA-1 mRNA were assayed by RT-PCR. *P < 0.05. (C) Schematic diagram of Nup98-galectin-3 interactions and cellular pathways. In the canonical condition (left), Nup98 interacts with galectin-3 to transport it to the cytoplasm. Nuclear β-catenin activates transcription of its target genes, including cyclin D1 and FRA-1. In the non-canonical condition, (e.g., low Nup98 levels or phosphorylation mutation in galectin-3 [right]), galectin-3 is not subject to export but remains in the nucleus. Nuclear galectin-3 “traps” β-catenin, which suppresses transcription of β-catenin target genes, followed by growth inhibition. N98: Nup98; Gal-3: galectin-3; β-cat: β-catenin.

4. Discussion

Nucleoporin Nup98 is a component of the NPC. Nup98’s N-terminal contains FG and GLFG repeat motifs and is bisected by a small coiled-coil domain that binds to the β-propeller nucleoporin Rae1; its C terminus is a domain with a unique, β-sandwich structure that controls autoproteolytic activity and is also important for directing Nup98 to the NPC. The GLFG repeat region of Nup98 also associates with nuclear transport receptors including karyopherins/importins. Nup98/homeodomain translocations are often found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients but are also related to chronic myeloid leukemia and pre-leukemic myelodysplastic syndrome [2].

We have shown here that nucleoporin Nup98 specifically regulates nucleus–cytoplasm translocation of galectin-3, which is implicated in malignant transformation and progression of cancer cells. We found that (i) Nup98 interacts with galectin-3, (ii) Nup98 promotes nuclear export of galectin-3, (iii) Nup98 depletion induces nuclear localization of galectin-3 and cell growth inhibition, and (iv) Nup98 expression affects the β-catenin signaling pathway through galectin-3 localization (Fig. 4C).

Our data showed Nup98 to interact with the C-terminal domain of galectin-3, which is a carbohydrate-recognition domain with an affinity for β-galactoside-containing glycoconjugates [9]. We have reported that this domain is also involved in the interaction with β-catenin [19], suggesting competition between Nup98 and β-catenin for galectin-3 binding leads to the regulation of β-catenin pathway. We have also shown that nuclear import of galectin-3 is regulated by karyopherins [10], but galectin-3 nuclear export is mediated by Nup98, not by nuclear export factor CRM1. This translocation to cytoplasm was suppressed by Nup98 depletion and also by phosphomutation of galectin-3. It has been suggested that phosphorylation of galectin-3 is critical to cell proliferation, anti-apoptotic property, malignant transformation, cancer formation, and also translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [14,20,21]. Our results showed that nuclear galectin-3 induced by Nup98 depletion and/or phospho-mutated galectin-3 binds and interrupts β-catenin, followed by growth inhibition, and supports previous studies including the report that increased levels of phosphorylated galectin-3 were seen in cytoplasm of proliferating cells [20].

β-catenin is associated with the APC multi-protein complex; the β-catenin signal pathway is required for development, and is frequently activated in cancer. β-catenin is a downstream component of the Wnt signaling pathway; it enters the nucleus where it cooperates with the transcription factor TCF/LEF and promotes expression of several target genes, such as cyclin D1. In this study, we showed that nuclear galectin-3 interacts with β-catenin to disturb the β-catenin pathway, and Nup98 depletion downregulates β-catenin signaling with galectin-3 nuclear localization.

Nucleoporins have been implicated in several cancers and leukemias, but the mechanism of their role in cancer progression is still largely unknown. Several studies have shown individual nucleoporins to regulate NPC function and nucleus–cytoplasm translocation, in unique ways. We recently revealed a key possible mechanism in cancer progression by nucleoporins [2,16,17]. Most cancers exhibit a complex pattern of chromosomal abnormalities including aneuploidy—thought to be caused by aberrant chromosome segregation during mitosis. We found that proper expression of nucleoporin Tpr and Nup88 is critical in preventing aneuploidy formation and tumorigenesis; nucleoporin Rae1, which is the binding partner of Nup98, also orchestrates Nup98-mediated leukemogenesis by regulating chromosome segregation [2,16]. Moreover we recently demonstrated that Tpr interacts with tumor suppressor p53 and regulates autophagy in cancer cells [22]. The finding presented here revealed Nup98’s molecular interaction with several cancer-related factors, and offers new insight into the mechanism of nucleoporin-mediated cancer progression.

Nucleocytoplasmic transport is critical to fundamental biological processes in which nucleoporins have essential roles. As cancer-related proteins that shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus usually associate with nucleoporins, regulating nucleoporin function would be a new concept for cancer therapy. For example, some nucleoporins such as Nup98 might also potentially regulate nuclear export of tumor suppressors p53 or BRCA to promote cancer formation. Although further studies are required to examine the role of nucleoporins in the mechanism of cancer progression, understanding the mechanism and control of nucleoporin function in different cancers would provide a new therapeutic target/modality for treating cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Akiko Kobayashi and Eriko Tsuka for technical assistance. This study was supported by MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) 23701049 (to T.F.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 23310151 (to R.W.W.), the National Institute of Health grant R37CA46120 (to A.R.). This study was also supported by a grant from Takeda Science Foundation (to T.F.).

Abbreviations

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- CK1

casein kinase 1

- NPC

nuclear pore complex

- Nup

nucleoporin

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Tpr

translocated promoter region

References

- 1.Xu S, Powers MA. Nuclear pore proteins and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:620–630. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funasaka T, Wong RW. The role of nuclear pore complex in tumor microenvironment and metastasis. Cancer Metas Rev. 2011;30:239–251. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9287-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran EJ, Wente SR. Dynamic nuclear pore complexes: life on the edge. Cell. 2006;125:1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez N, Alonso A, Moragues MD, Ponton J, Schneider J. The nuclear pore complex protein Nup88 is overexpressed in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5408–5411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao J, Salari K, Bocanegra M, Choi YL, Girard L, Gandhi J, Kwei KA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wang P, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Pollack JR. Molecular profiling of breast cancer cell lines defines relevant tumor models and provides a resource for cancer gene discovery. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gough SM, Slape CI, Aplan PD. NUP98 gene fusions and hematopoietic malignancies: common themes and new biologic insights. Blood. 2011;118:6247–6257. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-328880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soman NR, Correa P, Ruiz BA, Wogan GN. The TPR-MET oncogenic rearrangement is present and expressed in human gastric carcinoma and precursor lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins as modulators of tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:29–41. doi: 10.1038/nrc1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takenaka Y, Fukumori T, Raz A. Galectin-3 and metastasis. Glycoconj J. 2004;19:543–549. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000014084.01324.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakahara S, Hogan V, Inohara H, Raz A. Importin-mediated nuclear translocation of galectin-3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39649–39659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Califice S, Castronovo V, Bracke M, van den Brûle F. Dual activities of galectin-3 in human prostate cancer: tumor suppression of nuclear galectin-3 vs tumor promotion of cytoplasmic galectin-3. Oncogene. 2004;23:7527–7536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellerhorst JA, Stephens LC, Nguyen T, Xu XC. Effects of galectin-3 expression on growth and tumorigenicity of the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Prostate. 2002;50:64–70. doi: 10.1002/pros.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honjo Y, Inohara H, Akahani S, Yoshii T, Takenaka Y, Yoshida J, Hattori K, Tomiyama Y, Raz A, Kubo T. Expression of cytoplasmic galectin-3 as a prognostic marker in tongue carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4635–4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takenaka Y, Fukumori T, Yoshii T, Oka N, Inohara H, Kim HR, Bresalier RS, Raz A. Nuclear export of phosphorylated galectin-3 regulates its antiapoptotic activity in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4395–4406. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4395-4406.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonifaci N, Moroianu J, Radu A, Blobel G. Karyopherin β2 mediates nuclear import of a mRNA binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5055–5060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funasaka T, Nakano H, Wu Y, Hashizume C, Gu L, Nakamura T, Wang W, Zhou P, Moore MA, Sato H, Wong RW. RNA export factor RAE1 contributes to NUP98-HOXA9-mediated leukemogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1456–1467. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakano H, Funasaka T, Hashizume C, Wong RW. Nucleoporin translocated promoter region (Tpr) associates with dynein complex, preventing chromosome lagging formation during mitosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10841–10849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsay YG, Lin NY, Voss PG, Patterson RJ, Wang JL. Export of galectin-3 from nuclei of digitonin-permeabilized mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:250–261. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimura T, Takenaka Y, Tsutsumi S, Hogan V, Kikuchi A, Raz A. Galectin-3, a novel binding partner of β-catenin. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6363–6367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowles EA, Agrwal N, Anderson RL, Wang JL. Carbohydrate-binding protein 35. Isoelectric points of the polypeptide and a phosphorylated derivative. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17706–17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazurek N, Sun YJ, Price JE, Ramdas L, Schober W, Nangia-Makker P, Byrd JC, Raz A, Bresalier RS. Phosphorylation of galectin-3 contributes to malignant transformation of human epithelial cells via modulation of unique sets of genes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10767–10775. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funasaka T, Tsuka E, Wong RW. Regulation of autophagy by nucleoporin Tpr. Sci Rep. 2012;2:878. doi: 10.1038/srep00878. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep00878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]