Abstract

Suicide is a preventable public health problem and a leading cause of death in the United States. Despite recognized need for community-based strategies for suicide prevention, most suicide prevention programs focus on individual-level change. This article presents seven first person accounts of Finding the Light Within, a community mobilization initiative to reduce the stigma associated with suicide through public arts participation that took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from 2011 through 2012. The stigma associated with suicide is a major challenge to suicide prevention, erecting social barriers to effective prevention and treatment and enhancing risk factors for people struggling with suicidal ideation and recovery after losing a loved one to suicide. This project engaged a large and diverse audience and built a new community around suicide prevention through participatory public art, including community design and production of a large public mural about suicide, storytelling and art workshops, and a storytelling website. We present this project as a model for how arts participation can address suicide on multiple fronts—from raising awareness and reducing stigma, to promoting community recovery, to providing healing for people and communities in need.

Keywords: Suicide, Stigma, Community engagement, Recovery, Public art

Introduction

Suicide is a preventable public health problem. In the United States, almost 37,000 people died by suicide in 2009 (American Association of Suicidology 2012) and annually over 650,000 people receive emergency services after a suicide attempt (Goldsmith 2002). Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 24–35 years olds and the third leading cause of death among 15–24 years olds (CDC 2010); in 2010, suicide was the only leading cause of death to show a significant increase (Kochanek et al. 2011). Furthermore, research indicates that the prevalence of suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation are all underestimated (Crosby et al. 2011). The national response to this major public health problem received greater attention in 1999 with the U.S. Surgeon General’s report on suicide (US Public Health Service 1999), which was recently updated with the 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (US Department of Health and Human Services and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention 2012).

Despite the national recognition in both of those reports of the need for community-based responses to suicide, suicide remains largely addressed as an individual issue rather than a social or public health problem (Knox et al. 2004). In particular, suicide continues to carry a stigma for those who struggle with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors, as well as for family and friends who have survived the death of a loved one by suicide (Sudak et al. 2008). We use the term stigma to refer to a blemish or mark indicative of diminished moral character or of a person being less than whole (Corrigan et al. 2005; Livingston and Boyd 2010), with social stigma referring to a publically acknowledged mark of devaluation. The stigma of suicide heightens key risk factors for suicide, including feelings of isolation (Joiner Jr. et al. 2009), guilt (Sudak et al. 2008), and shame (Scocco et al. 2012), and impedes individual help seeking and community-based prevention (Corrigan 2004; Knox et al. 2004, 2003). Yet, suicide prevention efforts continue to be dominated by interventions that are focused on recognizing warning signs and referring individuals to clinical services (Wexler and Gone 2012), rather than addressing the social and community contexts in which suicide occurs or can be prevented.

In this paper, we describe a community mobilization effort to address the issue of suicide. The initiative focused on suicide prevention and reduction of the stigma of suicide through public arts participation over an 18-month period in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This effort sought to address the issue of suicide by initiating a public narrative focused on the shared experiences of suicide survivors as well as stories of individual and community healing and resilience in the aftermath of suicide.

The focus on Philadelphia was prompted in part by the elevated suicide rate in Pennsylvania and, especially, in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania’s suicide rate (11 per 100,000) is significantly higher than neighboring New York (6.91) and New Jersey (6.71) (CDC 2011), and in Philadelphia, the rate of suicide attempts per 100,000 among African American youth (12.1) is significantly higher than that of nearby New York City (6.5) and Baltimore (7.8) (CDC 2011). Prompted by a recent surge of local suicides and recognizing the need for enhanced community-wide suicide prevention programming, the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and disAbility Services (DBHIDS), the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program (MAP), and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) partnered to address the crisis of suicide in their community by starting the Finding the Light Within project. Similar to the reorientation of a community in the aftermath of disaster (Cox and Perry 2011; Norris et al. 2008), Finding the Light Within sought to stimulate individual and community recovery from suicidal ideation, attempt, or death, through a process of community mobilization that moved from recognition and dialog to individual and collective healing. This effort sought public acknowledgement of suicide and its related stigma so as to promote community building, community resilience, and reduction of suicide stigma.

We describe this innovative community initiative by presenting a series of seven, brief first person accounts. Each first person account is the personal statement of the individual or pair who is listed as its author, thus providing testimony about their experiences in this project. We believe this format offers a unique 360° perspective on how participatory public art can be used as a mechanism for social change and community mobilization to address what is historically considered to be an individual mental health problem—suicide and its aftermath. We use the term “participatory public art” to refer to a creative process that relies on the active participation of community members in the collective production of art for public display or presentation, and often for permanent installation as in the case of a mural. Finding the Light Within represents such a process, in that it included the creation of a large permanent public mural about suicide that engaged more than 1,200 community members in its production. Research into art therapy has demonstrated that visual arts has numerous positive psychological and health outcomes (Stuckey and Nobel 2010), suggesting that large scale community involvement in a healing arts project could have substantial benefit. In addition, the initiative supported numerous storytelling and art workshops with community-wide participation and created a storytelling website for members of the community to share stories about their bereavement or mural-making experiences. And finally, Finding the Light Within resulted in considerable local publicity that promoted a public narrative of suicide and its aftermath that contained both stories of pain and suffering and ones of collective healing, resilience, and hope.

The first person accounts below are personal statements from leaders of the three sponsoring agencies, the lead muralist, a suicide researcher, and two community members who are suicide survivors. Each account describes the program from a unique perspective, and notably, each account independently discusses the need to reduce the stigma associated with suicide and how doing so promotes healing and furthers suicide prevention. Several accounts discuss how a community mobilization process centered on participatory public art can result not only in stigma reduction for suicide, but also offer an alternative healing and support mechanism for those grieving the loss of a loved one to suicide. Finally, a number of accounts discuss how participatory public art can serve as a catalyst for community-based change. Details of the program activities for this initiative are provided in Table 1 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Description of Finding the Light Within program activities

| Program elements | Description |

|---|---|

| Mural design | |

| Community engagement meetings | Mural Arts Program (MAP) facilitated multiple “town-hall” style meetings of up to 40 people to aide with the development of the design to bring the discussion of suicide to larger audiences |

| Art, photography, writing and collage workshops | MAP held art workshops and photo shoots for interested participants. These workshops served to build community and dialog around suicide and to shape the design |

| Mural painting | |

| Open studio | MAP provided times when people could drop in and help paint the mural in a central accessible studio location. MAP also included painting on the Finding the Light Within mural on some of its public mural tours for visitors to Philadelphia. This allowed for the engagement with the project and the topic of suicide to reach many more people, including people from outside of Philadelphia |

| Community paint days | Project organizers held community paint days to target specific groups, including firefighters, high school youth, and clients of a local behavioral health agency, among others. These paint days provided opportunities for people to come together, acknowledge suicide, heal, and begin to remove social taboos about suicide |

| Installation and dedication | A public dedication ceremony took place in fall 2012 to celebrate completion of the mural. The ceremony included talks from prominent area leaders |

| Related arts activities | |

| Storytelling workshop | The storytelling workshop was run by a licensed clinical psychologist who is a professional creative writer. The workshop provided an opportunity for survivors and attempters to develop and share their stories of suicide in an environment safe from the stigma attached to suicide |

| First person arts festival | Professional actors adapted participant’s stories and performed them at the Philadelphia First Person Arts festival. This provided a public venue to expand the project’s impact |

| Storytelling website | The website (http://www.storytellingmural.org/) provides a forum to read other people’s stories about suicide, develop and post their own story, and find links to suicide resources. The website provides guidelines and tips for developing and writing one’s story |

Fig. 1.

Completed Finding the Light Within mural

Perspectives on Finding the Light Within

Arthur C. Evans and Samantha Matlin, City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services

Since 2004 Philadelphia’s behavioral health system of care has been guided by principles of individual and community recovery (Evans et al. 2012). Whereas individual recovery focuses on the reconstruction of citizenship for individuals struggling with mental health problems and addictions, a community recovery framework recognizes that entire communities may be in need of healing and that the individuals who have traditionally been branded as having harmed the community can themselves become healing forces within their communities (White et al. 2010). We began partnering with the Mural Arts Program after learning about their community-based process for mural creation, through which old relationships are rekindled and new relationships formed, creating a connected and empowered community. Over the past 4 years, we have partnered to complete murals that focus on mental health and substance use, as well as faith and spirituality, homelessness, trauma, and building community relations. Consistent with community psychology principles, the transformation that a community goes through due to Mural Arts Program projects is exactly what we are trying to do in terms of community recovery, particularly around reducing stigma and mobilizing communities for positive change.

The mural arts processes can educate people about behavioral health conditions in a nonthreatening fashion and engage people that we would otherwise not be able to engage. Compared to a typical public forum on mental illness, many more people participate in a mural project. The process is also different from the traditional therapeutic model and has the ability to destigmatize behavioral health issues both for people with behavioral health challenges and the broader community. The heart of this work is to give expression to the concerns and aspirations of those who have been silenced, traumatized, or excluded. The original intention for Finding the Light Within was to reduce stigma and educate communities. Suicide affects many different people from all walks of life, yet people usually do not talk about suicide in the way someone would talk of a death by car accident or illness. As a result, people often suffer in isolation. Through Finding the Light Within people have reported experiencing a healing process because they have been able to honor a loved one who passed away due to suicide and make personal connections with others with similar experiences. In addition to individual benefits, we sought to have an impact on the broader community and to raise people’s awareness.

One example of engaging a community in need was the participation of the city’s firefighters. The public safety community in general is not known for sharing feelings. It can be difficult for those communities where people have to be strong for everyone else to think about how their work impacts them on a personal level. Last year there were three firefighters that committed suicide in Philadelphia, and so we invited the city’s firefighter community to be a part of this project. Dozens of firefighters and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) came to the paint days where those firefighters were being honored. The project became a part of the city’s healing process around these three individuals.

The project was not just about the completion of the mural, but really proceeded through various engagement opportunities. Each community paint day drew large crowds and we reached physical capacity at all of our workshop spaces. We had storytelling workshops led by a psychologist, who was able to draw from the group some of the themes that went into the mural, but also, as a psychologist, understood and managed the feelings that were raised. We engaged a social worker who focuses on suicide. He helped develop a storytelling website to accompany the workshop and mural, to give voice to more individuals around this experience, and to provide expanded opportunities for healing. We connected with a festival here called the First Person Arts Festival. The people who participated in the storytelling workshop developed scripts for the festival that talked about the lives of the people they lost to suicide, and then professional actors presented those scripts. Outlets like that help this work live beyond the mural.

Having listened to people talk about the project, it is apparent that it has been an extraordinary healing process. Each person featured in the mural either passed away because of suicide, is a survivor of suicide, that is, a family member or friend of someone who passed away, or is someone who has struggled with depression and suicide in their own life. Many of the participants have decided that the relationships they made through this project are important to continue outside of the project. In this way we have seen enhanced social support come from this project. One participant shared that she had come to a paint day and someone was working on her panel, and she thought that it was wonderful that someone cared enough to help paint her child. That interplay of personal healing and expression with a way for people to connect with others has characterized this project and made it a success.

Jane Golden and Cathy Harris, Philadelphia Mural Arts Program

We see art as a catalyst for healing because when people are engaged in creating they no longer feel alone. At first people engage with others, but then by engaging in the process, by painting over and over, they start to see themselves differently. This shift is helpful in itself because it represents change in how you perceive yourself and how other people perceive you. If you’re depressed, if you’re struggling with suicide, you feel like an outsider. But being part of a large community project helps people feel like they are part of the world and that they are not standing on the periphery. We see this work as providing an alternative therapeutic model to individuals, but also as a tool for brokering community discourse around difficult issues.

Every year we do mural projects with the Department of Behavioral Health that deal with an issue such as mental illness, addiction, homelessness, and trauma. Not only is suicide a tragedy anywhere, but Philadelphia was recently struck by a series of high profile suicides in the public safety community and our rate of youth suicide attempts is nearly twice that of the national average (CDC 2011). As a result of this crisis, we decided to do a project with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. In particular, we decided to try to reach diverse audiences, including African American youth who have a significantly higher suicide attempt rate in Philadelphia than in other comparable cities (CDC 2011). What we didn’t realize is that there was quite a large community interested in this particular topic, and over the last few years the work has created even a larger community. We estimate that over 1,200 people have worked on the project at some point, whether for 15 min or by coming to every activity.

At the center of this project was providing a safe environment for people to grieve and heal, to talk about their feelings, to meet other people, and to not feel alone. Also, people understood that what they brought to the project would be translated visually into something large scale and tangible, which will become a tool of inspiration to many others. They knew that they were working on something beautiful, as well as connecting to a greater good beyond themselves and their individual pain.

We try to use art to talk about difficult issues to the broader the community and to challenge people to think about our common humanity. People who are in a state of despair or people who have lost loved ones to suicide are not an aberration. We have a tendency to segregate people we see as different from us, but when you dig deeper, we’ve all had darker moments, we’ve all had pain, we’ve all suffered from trauma, and we’ve all been at a point where we questioned ourselves and our lives. When there is an honest, productive discourse, people can talk about what works, where the services are, and how do I get help. People can talk about how to assume some responsibility for others’ pain in the world, so that people do not just close the door, but look at each others’ worlds and see where they cross.

Murals are tools to get people to talk about their differences, find communalities, and engage in conversation that is meaningful and sometimes life altering. Suicide is going on, and the longer the issue stays in the dark, the more it stays in the dark, and we are not getting anywhere. If an art project inspires people to seek help, to get services, to connect with others, if that is our limit, then that is a wonderful thing. These are the best kinds of projects because they push the envelope about what public art can mean—it truly is “community-based public art social practice.” A community around creating the work is as important as the work itself. The process of creating art is noble, wonderful, rich, and difficult.

Catherine Siciliano, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

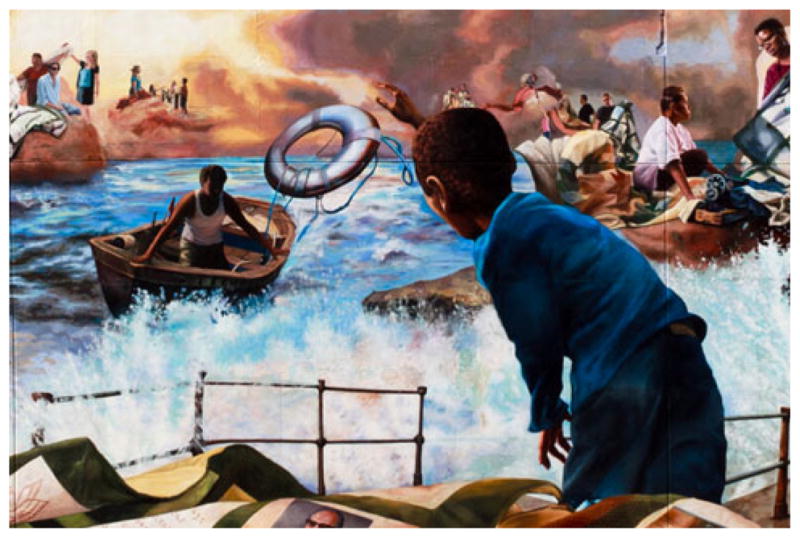

After losing my son Anthony, in 2008, I felt that the life preserver, the symbol of the AFSP and depicted in the mural being thrown to a boat in stormy seas, personifies exactly what survivors and attempters need to know. If you have been touched by the tragedy or if you are surrounded in that darkness, you need to be able to identify what your life preserver is and when to reach for it. Faith, family, friends and support groups are just a few of the life preservers that keep me afloat. The emotions and anxieties that surface with suicide are like a storm out at sea. You know it is coming, you can feel the waves get bigger and bigger and start crashing the shore. Those waves get so big you don’t know if they are just going to knock you over or if they are going to drown you. That’s why the life preserver is prominent in the mural, signifying what survivors and attempters need to be able to do—to reach for help (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Close-up of the center image in the Finding the Light Within mural

The Philadelphia Fire Department was headline news when a 22 year old firefighter took his life in 2011. There was so much turmoil surrounding his loss. So we organized a paint day for the Firefighters. I didn’t realize just how powerful it was going to be until I was watching these guys line up, some of them in full uniform, to join in painting the mural. The camaraderie and the support that you felt there was so incredible, not only for them, but also for myself and other survivors who were there. My son’s panel was ready that day and I was there painting with the support of my family and friends. Everyone there had the support of family, friends, and those who walk this path with them; surrounded by people who know and understand exactly what we are thinking and feeling and the difficult task of managing this unfathomable pain.

At first, I thought of the project as getting the message out; a permanent billboard that would break the silence and stigma. However, I now realize it was a healing process, not just for me, but for everyone who came out and painted a portion of the mural. The healing was evident in the hugging, the tears, and the friendships that were built. When I look at that mural I can identify the many faces on the mural, those lost and their survivors. It was not just one paint-day; it was paint-day after paint-day that these relationships formed. People built a lifeline of support. The project created an extended family. It was one of the most healing processes I have ever witnessed in the 3 years that I have been healing from this tragedy.

We need to break the silence and let people know that it is OK to talk about suicide. When you look at the mural, you see bright clouds and you see dark clouds. Some of those dark clouds were given to us by attempters, depicting how they feel when they are surrounded in darkness. The very reason they pull down the shades and turn out the lights is because the light hurts. That is why we called the project Finding the Light Within—you need to be able to find that light, to reach for the life preserver, to get past that darkness.

It is my hope and belief that this project will continue to bring about healing through the relationships that we formed. Survivors need to find a way to heal in order to find peace in their lives and the mural provided that path. It gives survivors a voice, a voice to say, “Hey, pay attention. This is going on and you’re not paying attention until it hits you. We want you to pay attention now. We need your attention now. Don’t wait until it is at your door.” Society thinks that eventually our lives just go on after our loss but they don’t—we’re stuck. We don’t have those anniversaries or birthdays. My nephew got married recently; he and my son were only a few months apart. I felt like the freak in the room that couldn’t stop crying. I wasn’t crying because I know I will never see my son get married, but because I don’t have those days for him anymore. No Birthdays, or moments to share. But those paint days were ours. They were days that we got to say, “We haven’t forgotten them, this pain is still with us.” They were days that we got support and did not have to mask our sadness.

James Burns, Lead Muralist

In mid-2011 I was asked to work on a project to help raise awareness about suicide. My first thought was what does that look like? And how do you create an image around suicide that gets the message across without being too graphic? Immediately I started to think of how this project could reach people. I talked to my mother who had lost her father to suicide at an early age, and soon after agreeing to the project I found out that a friend from graduate school had taken his life. Toward the end of the mural installation I also heard news of a friend from high school who had taken his own life—it was truly heartbreaking.

We engaged in a number of activities to move toward building a community of individuals involved in the project. We had a storytelling workshop of seven to eight people who had either struggled with depression and suicide, but were no longer in crisis, or had lost someone to suicide. From those stories we developed multiple scripts that were acted out in another community engagement venue where we had a full crowd. We also developed the website so that individuals could share their stories as a resource for others dealing with or contemplating suicide. We set up collage workshops with families who had lost someone and individuals at risk. There were photo shoots at the behavioral health clinic where the mural is and with the families involved in the project at our painting studio. These photos were used as source material for the mural. There was also a community conversation series where we invited the community at large to come and be a part of the dialogue. I showed sources of inspiration and my sketches and used the images to facilitate conversation about the topic. The design took months to take shape and evolved through a process that allowed for a lot of community input.

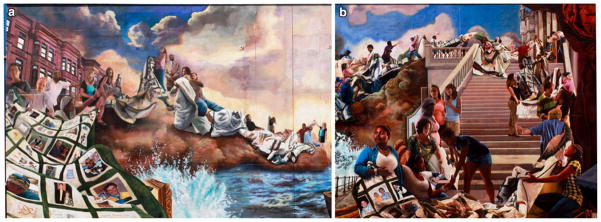

The inspiration for the design came from an image that I tore out of a magazine years prior. It was The Apotheosis of Spain by Tiepello, a Roccoco era painter whose paintings had figures dancing through the clouds. I greatly enjoyed the dissolve between the earthly and what seemed like the afterlife. I was excited by the air in these paintings and how the here and now and the afterlife became one. I thought this would be a good place to start for a project that was so emotionally charged. Through the meetings with the community members, the design evolved. The idea of water became important. People dealing with depression often talk about being under water with the tumultuousness of waves crashing. The image of a boy who is throwing a life preserver to someone who is in troubled water is the central image. The idea of the quilt, though, emerged as the foundation for the design. As part of their Out of the Darkness Walk, AFSP creates quilts with the images people submit of their loved ones who have been lost to suicide. I wanted the quilt to appear to go on infinitely, moving in a circular fashion. The quilt manifests as a second life-ring in the composition and a metaphor for the survivors and support network that exists for those struggling with loss and with mental health issues—community encapsulates the crisis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a Close-up of the left side of the Finding the Light Within mural showing the quilt and community of people carrying the quilt. b Close-up of the right side of the Finding the Light Within mural showing the quilt and community of people carrying the quilt

Once the design was completed, we held a number of community paint days to engage people in Philadelphia and abroad in the painting process. We worked out of store fronts that had been vacant and were in high traffic areas to help raise awareness. We did 6 public events, and at each one there were roughly 100 people in attendance. We also worked with our tours program. Mural Arts does trolley tours where people can take a ride through the city and see the murals and some tours involve people in the painting process when possible and help to raise awareness. We did a number of engagements with the tour group. We had local schools involved and alumni groups from the University of Pennsylvania, as well as a number of other groups big and small. In total there were 1,200 volunteer hands involved in the painting of the mural through the tours program and public paint days.

I enlisted people involved in the project to submit images of the loved ones that they lost. With each passing event we added more images. One of the young women involved sent me a bunch of images of her and her boyfriend who committed suicide; so they actually appear in the mural in different modes, one where they are together and another where she is by herself and he is by himself on the other side of the composition sitting in the clouds. I took a little bit of personal liberty by including my grandfather and two friends. As an artist and public servant, I felt a responsibility to offer participation in the project and representation on the mural to as many people as possible, to have them and their loved ones be part of it.

Many people expressed gratitude to me to be able to be around other people who were dealing with similar issues. I saw the project helping with the shame that is attached to suicide. One woman whose son had committed suicide, for example, was very hesitant at first, but later on sent me an email saying that she really appreciated being around other family members who have dealt with this. I invited her to paint whenever she wanted, but she wanted to be there when the other families were there. Families would say that they were not sure they wanted to be there, then as the project took hold, they would start to overcome the stigma. The project became an opportunity for the families to come together and celebrate the person.

The project has been both incredibly startling and rewarding. Startling to learn how big this problem is and meet so many people who have dealt with such untimely loss. Rewarding to have been involved in bringing together individuals who have dealt with suicide and providing a venue for acknowledging the problem together and attacking the stigma that exists. Through face to face conversations and local media outlets, we were able to take something that is hard to talk about and often seen as shameful into the public in a way that allows the social structure to acknowledge the problem in a different way. The work is not just on the wall. It was working with people and inspiring them to get involved in their respective communities in new ways.

We need to continue to do more to destigmatize suicide, whether it is a mural or a walk, a public forum or dialog. I don’t think there is any one way to do it—the important thing is to maintain a public dialog and not allow it to remain a counseling room discussion. We can’t let the conversation pass behind closed doors. It has to be a public dialog.

Jonathan Singer, Project Consultant and Suicide Researcher

I have worn two hats in this project: suicide prevention consultant, and developer and moderator of the storytelling website. [The lead muralist] contacted me early in the project to talk about suicide prevention and intervention. During our conversation, he asked me a question that inspired the idea of the storytelling website: “Where do you think would be a good place to put a suicide prevention mural?” My first thought was, nowhere and everywhere. There is no one place that represents suicide prevention or loss. Suicide prevention should be everywhere because suicide touches the lives of people everywhere. But, “everywhere” is not realistic. While we were talking about this conundrum, he mentioned that there was going to be a writing component to the project. I had the idea that we could create a storytelling website to go along with the mural. It would be a place where people could share their stories about being a survivor of suicide, of helping someone through a suicidal crisis, or of struggling with their own ideation or behaviors. The idea of a web-based storytelling companion to the mural addressed the issue of suicide prevention being everywhere, because the internet is everywhere. Someone could access the website at 2 a.m. during a suicidal crisis, or noon on the day of the 25th anniversary of a partner’s suicide. People are not going to go out and look at a mural at 2 a.m., but they can hop on the web and be reminded that they are part of a community.

My hope for the storytelling website was that it would be a tool for healing and connection. There’s a small body of research that suggests that “expressive writing” can help people process traumatic events, including suicide (Penne-baker and Chung 2011; Whiteford et al. 2012). While the storytelling website is not an expressive writing project, I hope that after writing and sharing stories of surviving the suicide of a loved one or moving through a suicidal crisis people will feel less lonely, more connected, and more comfortable “going public.” Someone who is currently suicidal could read these stories and find hope, knowing that others have been there and survived. It is important to mention that because stories that glorify suicide can exacerbate suicide risk, rather than reduce it (Hassan 1995), we have strict guidelines on the website about story content. Dr. Terri Erbacher of the Delaware County Suicide Prevention Task Force and I also moderate the stories to make sure they follow the media reporting guidelines for suicide (www.sprc.org/library/sreporting.pdf).

One of the critiques of first-generation suicide awareness programs was that they normalized suicide by telling youth that “everybody has these thoughts.” That is not true. While well-intended, a better message—and the one that we hope to convey through this project—is “when you are in a suicidal crisis, or have lost a loved one to suicide, know that you are not alone; there is a community waiting to support you.” This message has been used to reduce stigma associated with diabetes and cancer. But, it has been very hard to have that conversation because suicide is seen as an individual problem.

One of the ways that change will happen is through conversation. Having this public arts project around suicide moves the conversation from being within the domain of professionals and survivors to the public domain and all of those informal networks. I can’t imagine that people could look at the mural and not talk about it. “Why is someone throwing a life preserver? Why is that person a boy? Is suicide a big problem among youth? Why is he black? Is suicide an issue among Black Americans? Who are the people on the quilt? Does the quilt really exist or is it a metaphor?” From there the conversation might become personal, “Do you know anyone who has ever been suicidal? Have you ever thought that your life isn’t worth living?” Ideally, there would be a ripple-effect. Conversations would happen because of newspaper articles about the mural and the website, when schools get their students involved in telling their stories, and when people see the mural as part of the Mural Arts Tour. For the first time people would have water cooler conversations about suicide prevention in the office, the bedroom, on Facebook and Twitter.

If the mural is a way to start conversations about suicide, then the website is a venue for telling the story of suicide. At a societal level, the story of suicide isn’t told, and this creates a lethal feedback loop: isolation increases suicide risk; people don’t talk about feeling suicidal because of shame and stigma; not talking increases the sense of isolation, which in turn increases suicide risk. The project gives those who are suicidal, or who are survivors, legitimacy in expressing their experience. Several people during the creation of the mural and website went public for the first time about their own experiences of either being suicidal or losing somebody that they loved to suicide. The project has potential to take conversation about suicide from being an individual stigma and personal problem to making it a public or social issue. That is an important shift for suicide prevention.

Guy Kiernan, Community Member and Suicide Survivor

One of the biggest challenges with suicide is how much it affects the people surviving, outside of even the direct survivors. I had a close uncle who had committed suicide, but had never thought about how my uncle’s suicide had affected me. When I first got involved in this project, I felt almost like I didn’t have a right to be at the workshops because it wasn’t my parent, my best friend, or my child that died. Through the project, especially the writing workshop, I started to find out how my uncle’s suicide had influenced me and my relationships with people. I came to see how the suicide and my reaction to it had trickled down without my being as conscious of that one event as I thought I was. If nothing else, being part of this project has brought me together with a group of people who all can relate to the same thing. Suicide is not something you want to talk about with your buddies out at the bar. So to have all these people affected by the same thing in a room where we could talk about it was really good.

What people are going to get out of the project is different for everyone—whatever it can do for you, whether it helps you heal, or move on, or try to understand. The writing process helped me gain some clarity and have more understanding of things I hadn’t thought of before. We might like the project to solve all the world’s problems, with people realizing suicide is not the answer, but in reality I think that is a lot to expect. It may be kind of cliché, but if it helps one person to decide that maybe there is a better way to go about their problems, or if it helps another person think about and come to terms with why someone killed themselves, if it helps heal someone or gives them a little bit of understanding, then it has done its job.

Margaret Pelleritti, Community Member and Suicide Survivor

Being involved in Finding the Light Within has just been phenomenal. It has been so touching for me to know that there will be something lasting and life-long that will be a memory for my son. I heard about the project through my involvement with AFSP—I lost my son Michael to suicide. At the first meeting with the City of Philadelphia and the Mural Arts Program, we were told that there was going to be a mural to depict people who had died by suicide in Philadelphia. It was like a town hall meeting, with people just throwing different ideas around. After the initial meeting, we met at the Gallery [a downtown mall] with [the lead muralist]. People brought pictures of their loved ones that had died by suicide. [The lead muralist] provided an overall scenario of what was going to happen. He didn’t have the whole canvas laid out, but he explained how different pictures might be. I had sent him a few pictures of my son at different ages, and the one that he chose for the mural is of my son and daughter.

I heard about the writing workshop through AFSP too. I had seen a flier that they were going to do four or five closed writing workshops and that you had to commit to all of the workshops. Even though my son has been gone for a long time in society’s eyes, I had never written about it. I’ve done public speaking and talked to other survivors, but I thought that it would be healing to actually put pen to paper. When I lost my son I had to go to counseling, and counseling saved my life. Counseling was very healing one-on-one, but to be in a room with complete strangers, except that we shared the core theme of suicide, whether losing someone or someone attempting it, there was this common denominator. I wouldn’t say it was like taking a band-aid off because when you lose someone to suicide the scar is always there, especially with the stigma in our society. But that writing was the most powerful, most moving, most positive thing for me because what we would write we would share. The leader of the group helped each of us to bring out different aspects of our stories. For me, when my son died by suicide he was 16 and my daughter was 13, and one of the questions she asked me that I had never addressed was, “What kept you going?” When you lose someone to suicide, personally, you give up, you don’t want to go further, and to realize my will to go on was my daughter, to add that to the story was a life opener moment. It would have been easier to say I can’t go any further, but from doing these things around suicide—whether it’s the mural arts, whether it’s the writing memoirs, whether its public speaking—it gives a voice to help other people realize that if they are in that same situation they can pick up keep going.

The bond we formed in the writing workshop was like a rope tied around us. When we saw each other at the paint days it was like little kids out on the playground—this is my little group here. We had shared so much. To actually hear someone share their writing about their lowest moment when they had attempted or had tried to commit suicide or from someone who had lost someone, it was such an eye opener. The bonds are so tight.

The painting was very permanent. When you put the brush into the paint, you know that what you are doing is something very lasting for someone that you love. My daughter and I went together for a few paint days. The last one was my son’s face. It was overwhelming for me, and my daughter finished his face. Even though I have photographs and mementos, to see his face painted was breathtaking. It is not that it finalizes anything because you know your loved one is gone. But it is like fireworks to see that yes it did happen, but here is a mural that says that this person was here, and all the other faces too.

I hope this project can help spread the word. It used to be you couldn’t say the word “suicide,” you couldn’t say it because people assumed you were going give people ideas. When my son passed away you couldn’t even go into schools and talk about suicide. To see now that you can do that, the doors are opening a little, is refreshing. By sharing anyone’s story, whether it is someone who attempted or someone who lost someone, by sharing these stories we are hopefully creating a light bulb moment for someone to realize I feel this way, or I don’t want my mother to feel this way. It is important to create some kind of exclamation point that people will realize I do want to live, whether it is something like the Out of the Darkness Walk or the Finding the Light Within mural, to save lives so that there are not more survivors.

My son has been gone now 19 years. Along the way I have grown. When I lost my son I was married and my highest level of education was a high school diploma. A few years later we divorced and I went back to college and got my bachelors and masters and now I am working on my Ph.D. So I keep going forward, always trying to keep my son’s memory alive, through me and my daughter. Trying to get society’s support is usually empty, so it is through programs like this that we can create or increase society’s awareness. The project helps me to keep my son’s memory alive because there are no grandchildren, daughter-in-laws, or anything in that way. It helps me to remember also this young man was here, this young man mattered, this young man had a life. For anyone who goes by and sees the mural, or reads what we wrote, they may realize, “Wow, there was a life that mattered.”

Discussion

Finding the Light Within was a multi-faceted approach to suicide stigma reduction and collective healing through public art. The permanent mural will remain a fixture of Philadelphia for years to come. The first person accounts we present suggest that the process of creating the mural reduced stigma, built community, and contributed to individual and collective healing. The mural’s design is a symbolic representation of AFSP’s central message: identify your life-saver and know when to reach for it. In addition, the mural depicts the lives of people touched by suicide as well as and the community of support that they form and by which they are surrounded. The image embodies the mutual aid axiom of “we’re in the same boat.” Both the mural design and the painting of the mural came together through numerous large community engagement events, thereby opening dialog with diverse audiences in Philadelphia, the region, and beyond. The storytelling workshops also shaped the design, while providing a powerful healing space for participants to share their stories and emotions around suicide in a setting free from the social stigma. And the storytelling website extends the space of the workshop to a virtual environment, providing not only opportunity for learning and sharing, but also access to resources for people in need from anywhere in the world, any time of the day.

Each co-author addressed in their first person accounts two simultaneous functions of the project: (1) reduce the stigma around suicide and engage a broad community in dialog; and (2) create a safe space for individual and collective healing in the aftermath of suicide. Arthur Evans and Samantha Matlin of DBHIDS highlighted the goals of the project as stigma reduction and enhanced community engagement, and cited program impacts of reduced sense of isolation, increased social support and connectedness, and individual and collective healing. Catherine Siciliano from AFSP noted that, although the original goal was stigma reduction and “breaking the silence,” the project became a powerful healing journey for individuals and entire communities, especially for survivors. Jane Golden and Cathy Harris of the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program spoke to the ability of art to act as a catalyst for healing, but also focused on how this project established a safe space to engage in a dialog about suicide and establish a common sense of humanity around this tragedy. Lead muralist James Burns expressed his hope that the process and mural would establish a public dialog about suicide so that the topic did not remain “behind closed doors.” He also observed a reduced shame in participants from when they first engaged in the project. Suicide researcher Jonathan Singer discussed how the project connected to stigma reduction and suicide prevention theory, in particular by reducing people’s sense of isolation, emphasizing suicide as a social issue, and establishing a public dialog.

Although many of the project’s leaders were themselves survivors of suicide and participants in the project, the two community member accounts highlight a slightly different focus. Whereas the project organizers all emphasized stigma reduction and collective healing, Guy Kiernan and Margaret Pelleritti singled out the opportunity for personal healing that the project provided. Guy discussed how his participation in the storytelling workshop led to new insights and helped him heal by finding a sense of commonality with others. For Margaret, healing came in two forms: first, the storytelling workshop and paint days helped her better understand her own healing journey through connections with others; and second, the mural functioned as a memorial honoring and celebrating her son. Catherine Siciliano also noted how the mural created an opportunity to remember and honor her son. What exactly it means to heal from a permanent loss is always a difficult question. For the people who participated in this project, healing came in the form of an enhanced social network, freedom to talk about their experience with others who could understand them, and an opportunity to honor those who died.

Implications

Finding the Light Within engaged a large and diverse audience and communicated critical messages about suicide that may strengthen suicide prevention efforts. As noted in a recent review of suicide prevention programs, such efforts often encounter institutional and social barriers that hinder successful interventions and pose challenges to implementing methodologically rigorous designs (Miller et al. 2010). This review, which focused on school based interventions, emphasizes that reducing the stigma of suicide may be a critical first step before successful implementation of prevention programs (Miller et al. 2010). As is well-documented in the literature and evident in each of these first person accounts, the stigma associated with suicide remains a significant impediment to community-based suicide prevention; reduction of this stigma and education of the community are critical to achieving reduction in suicide risk (Knox et al. 2003).

A number of co-authors identified the participation of the firefighters as particularly significant. Asking for help may be taboo among professionals whose job it is to be strong in the face of crisis (Woodfill 2012). Despite the fact that there are evidence-based prevention programs for adults, groups at higher risk for suicide, such as firefighters, may not access those services. One of the barriers suicide prevention programs within a traditional behavioral health framework is that an intervention requires that someone ask for help (Knox et al. 2003). Although it may be hard for many of us to admit when we need help, many first responders and military personnel do not disclose suicidal ideation for fear of losing their jobs (Hoge and Castro 2012). Therefore, when the firefighters participated in this community-wide public arts program they were able to not only to publicly acknowledge and grieve the suicide death of one of their coworkers, but they were able to do so without needing to seek mental health services. Taking a community arts approach is a non-threatening way to bring suicide prevention activities to people who typically do not access behavioral health services. Although there are no data to suggest that the Finding the Light Within project prevented suicides, it adds a dimension to suicide prevention efforts that encourages connection to the community and publicly owning a possibly shameful or stigmatizing experience.

The project also appears to have had a profound impact on participants’ sense of connectedness and social support, which aligns with existing research that links community-based arts participation to improved social connectedness and mental health (Hacking et al. 2006). Research on community resilience in the face of disaster, highlights the critical role of social capital to enhancing resilience, including networking, social support, and community bonds (Norris et al. 2008), all of which appear to have been enhanced by this project according to the first person accounts. Sense of social connectedness is a protective factor for suicide (CDC 2008), whereas a sense of being isolated is a risk factor that is empirically linked to social and internalized stigma (Corrigan et al. 2005; Scocco et al. 2012). Furthermore, research suggests that family and social connectedness is especially critical to suicide prevention among African American youth (Matlin et al. 2011). For Finding the Light Within participants, the new-found social support provided a social network free of the social stigma around suicide and reduced feelings of isolation.

Public art is an activity that can draw interest from diverse groups of people, thereby enhancing the reach of community engagement efforts. The direct participation of over one thousand people from in and around Philadelphia testifies to this potential. Furthermore, Finding the Light Within generated significant and positive press, from interviews during the course of the project to news coverage of the mural dedication event. Positive and sensitive media communication is an important element of community recovery (Norris et al. 2008). Public art draws attention and can, thereby, heighten the visibility of challenging social issues.

Participatory public art also provides a model for engaging communities in recognizing and rejecting harmful public narratives, such as the social stigma around suicide. Cross-cultural suicide research suggests that suicidology not only may differ from cultural group to cultural group (Goldston et al. 2008), but that suicide may for some groups be better conceptualized as a social process that is best addressed through community-wide efforts (Chandler and Lalonde 1998; Wexler and Gone 2012). Finding the Light Within was just such a community-wide effort, utilizing participatory public art to attend to the social dimensions of suicide. Rappaport (2000) calls on community psychologists to identify the “tales of terror,” those stereotyping or stigmatizing public narratives that harm our communities, and turn them into “tales of joy,” such as community narratives portraying and promoting recovery, resilience, and social capital. Sarason (1972) emphasized the importance of creating settings that promote recovery and well-being. A public mural is an opportunity to do both—to change the physical and social environment through participatory public art and promote healing community narratives.

Conclusion

Because Finding the Light Within did not include a rigorous evaluation, we cannot identify specific impacts the project had on individual- and community-level outcomes. However, the project did demonstrate the feasibility of using participatory public art as a basis for engaging large and diverse groups of community participants in a suicide prevention initiative, many of whom might not otherwise have participated, such as firefighters. The first person accounts also provide encouraging evidence among participants of individual and community healing, social connectedness, and reduced feelings of stigma due to suicide.

Finding the Light Within rejects the stigma of suicide but recognizes the tragedy of it, while providing hope, connection, resources, and telling the story of a community pulling together. The mural not only addresses the social and mental landscape of suicide stigma, but also creates a permanent installation, a space, to sustain the dialog long after the production processes and activities are completed. The wide diversity of involvement in Finding the Light Within is a testament to the success of this project in enhancing community engagement. We believe that Finding the Light Within can serve as a model for other communities to address suicide on multiple fronts—from raising awareness and reducing stigma, to promoting community recovery, to providing healing for people in need. We also believe that this model may be applicable to other behavioral and social challenges, such as mental illness, addiction, violence, and homelessness.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Thomas B. Scattergood Foundation, and a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) research training grant (T32 DA 019426) to Jacob Kraemer Tebes.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10464-013-9581-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Nathaniel V. Mohatt, Email: nathaniel.mohatt@yale.edu, Division of Prevention and Community Research and The Consultation Center, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University, School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511-2369, USA

Jonathan B. Singer, Temple University College of Health Professions and Social Work, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Arthur C. Evans, Jr., Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Samantha L. Matlin, Division of Prevention and Community Research and The Consultation Center, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University, School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511-2369, USA. Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Jane Golden, City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Cathy Harris, City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

James Burns, City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Catherine Siciliano, Greater Philadelphia Chapter, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Guy Kiernan, Finding the Light Within Community Artists, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Margaret Pelleritti, Finding the Light Within Community Artists, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Jacob Kraemer Tebes, Division of Prevention and Community Research and The Consultation Center, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University, School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511-2369, USA.

References

- American Association of Suicidology. Suicide in the USA based on current (2009) statistics. 2012;2012 [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Strategic direction for the prevention of suicidal behavior: Promoting individual, family, and community connectedness to prevent suicidal behavior. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/Suicide_Strategic_Direction_Full_Version-a.pdf.

- CDC. Suicide: Facts at a Glance. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/Suicide_DataSheet-a.pdf.

- CDC. Youth risk behavior survey. 2011 Retrieved Aug 28, 2012, from www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs.

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s first nations. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):191. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kerr A, Knudsen L. The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11(3):179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cox RS, Perry KME. Like a fish out of water: Reconsidering disaster recovery and the role of place and social capital in community disaster resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3):395–411. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby AE, Ortega L, Melanson C. Self-directed violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans ACJ, Golden Heriza J, White WL. A photographic essay the art of recovery in Philadelphia: Murals as instruments of personal and community healing. 2012 retrieved Apr 1, 2013, from http://www.congress60.org/AppData/Document/2011-The-Art-of-Recovery-in-Philadelphia.pdf.

- Goldsmith SK. Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB, Molock SD, Whitbeck LB, Murakami JL, Zayas LH, Hall GCN. Cultural considerations in adolescent suicide prevention and psychosocial treatment. American Psychologist. 2008;63(1):14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacking S, Secker J, Kent L, Shenton J, Spandler H. Mental health and arts participation: The state of the art in England. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 2006;126(3):121. doi: 10.1177/1466424006064301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan R. Effects of newspaper stories on the incidence of suicide in Australia: A research note. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;29(3):480–483. doi: 10.3109/00048679509064957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA. Preventing suicides in US service members and veterans. JAMA. 2012;308(7):671–672. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Rudd MD. The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox KL, Conwell Y, Caine ED. If suicide is a public health problem, what are we doing to prevent it? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox KL, Litts DA, Talcott GW, Feig JC, Caine ED. Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US air force: Cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327(7428):1376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7428.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek KD, Jianquan X, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung HC. Deaths: Final data from 2009. National Vital Statistics Report. 2011;60(3):1–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(12):2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin SL, Molock SD, Tebes JK. Suicidality and depression among African American adolescents: The role of family and peer support and community connectedness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DN, Eckert TL, Mazza JJ. Suicide prevention programs in the schools: A review and public health perspective. School Psychology Review. 2010;38(2):168. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, Pfefferbaum RL. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(1):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. In: Friedman HS, editor. Oxford handbook of health psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. Community narratives: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(1):1–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1005161528817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason SB. The creation of settings and the future societies. Cambridge: Brookline Books; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Scocco P, Castriotta C, Toffol E, Preti A. Stigma of suicide attempt (STOSA) scale and stigma of suicide and suicide survivor (STOSASS) scale: Two new assessment tools. Psychiatry Research. 2012;200(2–3):872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(2):254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudak H, Maxim K, Carpenter M. Suicide and stigma: A review of the literature and personal reflections. Academic Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):136–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services, & National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Washington, D.C: HHS; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Public Health Service. The surgeon general’s call to action to prevent suicide. DC: Washington: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, Gone JP. Culturally responsive suicide prevention in indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(5):800–806. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Evans AC, Lamb R. Community recovery. 2010 Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://congress60.org/AppData/Document/2010-Community-Recovery.pdf.

- Whiteford D, DeBrule DS, Drapeau C. Reducing depression and anxiety for suicide survivors with an innovative writing intervention. Paper presented at the 45th American Association on Suicidology Annual Conference; Baltimore, MD. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Woodfill DS. Alarm goes off over firefighter-suicide rate. Phoenix; Arizona Republic: 2012. [Google Scholar]