Abstract

Background

Activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of HER2 (ERBB2) have been described in a subset of lung adenocarcinomas (ADCs) and are mutually exclusive with EGFR and KRAS mutations. The prevalence, clinicopathologic characteristics, prognostic implications, and molecular heterogeneity of HER2-mutated lung ADCs are not well established in US patients.

Experimental Design

Lung ADC samples (n=1478) were first screened for mutations in EGFR (exons 19 and 21) and KRAS (exon 2) and negative cases were then assessed for HER2 mutations (exons 19–20) using a sizing assay and mass spectrometry. Testing for additional recurrent point mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, MEK1 and AKT was performed by mass spectrometry. ALK rearrangements and HER2 amplification were assessed by FISH.

Results

We identified 25 cases with HER2 mutations, representing 6% of EGFR/KRAS/ALK-negative specimens. Small insertions in exon 20 accounted for 96% (24/25) of the cases. Compared to insertions in EGFR exon 20, there was less variability, with 83% (20/24) being a 12bp insertion causing duplication of amino acids YVMA at codon 775. Morphologically, 92% (23/25) were moderately or poorly differentiated ADC. HER2 mutation was not associated with concurrent HER2 amplification in 11 cases tested for both. HER2 mutations were more frequent among never-smokers (p<0.0001) but there were no associations with sex, race, or stage.

Conclusions

HER2 mutations identify a distinct subset of lung ADCs. Given the high prevalence of lung cancer worldwide and the availability of standard and investigational therapies targeting HER2, routine clinical genotyping of lung ADC should include HER2.

Keywords: HER2, ERBB2, lung adenocarcinoma, EGFR, driver oncogenes

INTRODUCTION

The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2 / ERBB2) is a receptor tyrosine kinase of the ERBB family which includes three additional members: EGFR (HER1/ERBB1), HER3 (ERBB3) and HER4 (ERBB4). Ligand binding to the extracellular domain of EGFR, HER3 and HER4, results in the formation of catalytically active homo and heterodimers which, in turn, activate several downstream pathways involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis (1–3). Despite extensive structural homology with all other members of its family, both along the catalytic intracellular domain and the extracellular putative ligand binding region, HER2 has no identified direct ligand. Instead, it functions as the preferred dimerization partner for all other ERBB family receptors (4–6). This observed superior ability for heterodimerization, coupled with a unique basal tyrosine kinase activity, confers to HER2 a pivotal role in signal transduction with corresponding significant roles in cancer development and progression when its function is deregulated.

Deregulation of the HER2 gene, through protein over-expression and/or gene amplification, is found in many human cancers most notably breast, ovarian, gastric and some biologically aggressive forms of uterine carcinomas (7–10). In most cases, over-expression correlates with poor prognosis and, in breast and gastric cancers, it can also predict benefit from HER2 targeted therapy. Trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the extracellular domain of HER2, has shown significant survival advantage in the treatment of HER2 over-expressing breast cancer (8, 11) when combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Similar findings have also been recently reported in a phase III study of patients with HER2-positive gastric carcinoma (12). In contrast, while over-expression and amplification of HER2 has been reported in up to 1/3 of non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs) (13, 14), statistically significant differences in survival have not been observed (15) and trials exploring the advantage of treatment with trastuzumab have shown only modest or minimal clinical benefits (13, 16).

In 2004, activating mutations within the tyrosine kinase domain of the HER2 gene were discovered in a small subset of NSCLCs (17–22). Their prevalence is reported to be up to 4% (20, 22) and both in-vitro and in-vivo studies confirm the oncogenic potential of these mutations (23–25). In vitro studies have shown that tumor cells harboring the most prevalent HER2 insertion (YVMA) not only exhibit ligand-independent tyrosine phosphorylation and stronger association with downstream signal transducers that mediate cell survival and proliferative processes, but also potently induce EGFR transphosphorylation, even in the presence of a kinase-dead EGFR (23). Tumor cells harboring HER2 mutations are resistant to EGFR inhibitors but remain sensitive to both HER2 inhibitors and dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitors (25–27). The most commonly encountered mutations are in-frame insertions in exon 20, but point mutations along the tyrosine kinase domain have also been identified; all are mutually exclusive with common activating mutations in EGFR and KRAS (17, 20, 28). Based on published studies, the clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with HER2 mutations have been reported to be very similar to those with EGFR mutations, being more common in women, Asians, never smokers, and in adenocarcinoma (compared to squamous carcinoma) (20). To date, however, only a few studies focusing on HER2 mutations have been published (17–22) and most were performed in predominantly Asian patient populations. The incidence, clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic implications of HER2 mutant lung cancer in the US population remain to be more thoroughly defined.

In the current study, we aimed to 1) determine the frequency and spectrum of HER2 mutations in a large cohort of US patients with adenocarcinoma, 2) assess the clinical and histopathologic characteristics of HER2-mutant tumors, 3) confirm the mutually exclusive nature of mutations in other genes, including major and minor mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, MEK1 and AKT as well as ALK-rearrangements and 4) compare the survival of patients with HER2-mutant tumors to those harboring other mutually exclusive mutations.

METHODS

Patient selection and mutation analysis (Supplemental figure 1)

Clinical cases of lung adenocarcinoma received for routine, reflex clinical EGFR and KRAS testing (29) at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2010 were selected for the study. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue were reviewed for each sample to identify and circle the areas of highest tumor density. Macro-dissection was performed on corresponding unstained sections to ensure at least 25% tumor content. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Clinical testing for EGFR mutations was carried out using fragment analysis for the detection of small indels in exons 19 and 20 and the L858R mutation in exon 21 using previously described methods (30, 31). KRAS testing was performed by a combination of standard sequencing and mass spectrometry genotyping (Sequenom) based on methods previously described (32). As part of our standard panel of mutation analysis by mass spectrometry, all samples were also concurrently tested for other recurrent point mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, AKT, MAPK1 and PIK3CA (supplemental table 1)(33, 34). When sufficient tissue was available, samples that were EGFR/KRAS wild type were tested for ALK rearrangements by fluorescent in-situ hybridization (Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe Kit) using standard protocols.

HER2 mutation analysis

Cases which were negative for the predominant activating EGFR (Exon 19 deletion and L858R) and KRAS (G12 and G13) mutations were selected for HER2 testing, given the known mutually exclusive nature of these mutations. HER2 molecular analysis was carried out by 2 methods: a sizing assay to detect small indels in exon 20 and a Sequenom assay panel to detect specific point mutations including L755S, D769H, V777L and V777M. Testing by fragment analysis followed a protocol similar to EGFR testing with fluorescently labeled HER2 primers (30, 35, 36). Briefly, a 300-bp genomic DNA fragment encompassing the entire coding region of exon 20 was amplified using the primers FW1: 5′-GTT TGG GGG TGT GTG GTC T - 3′ and REV: 5′-Hex - CCT AGC CCC TTG TGG ACA TA - 3′. PCR products were subjected to capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Testing for recurrent point mutations was incorporated into the standard Sequenom testing panel with procedures as previously described using primers. All positive cases were confirmed and further characterized by Sanger sequencing using the above primers without fluorescent label.

To confirm the mutually exclusivity of HER2 exon 20 insertions with major EGFR and KRAS mutations, as well as other rarer mutations not well represented in our cohort, we also tested a separate set of adenocarcinomas with a known positive mutation profile and sufficient DNA. Also, to confirm that HER2 mutations were confined to adenocarcinomas, we also tested a separate set of squamous and small cell carcinomas following similar protocols.

Analysis of HER2 gene copy number alterations by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Assessment of HER2 gene copy number was performed on the same formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens used for DNA extraction. The Vysis PathVysion HER2 DNA Probe Kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) was used following standard manufacturer’s protocol. At least 40 cells were analyzed for each case by two reviewers and were classified according to published criteria (37, 38) as disomy, low polysomy (≤4 copies of HER2 in ≤40% of cells), high polysomy (>4 copies of HER2 in >40% of cells) or amplified (HER2/CEP17 ratio per cell ≥ 2, or homogeneously staining regions with ≥15 copies in ≥10% of the cells). Cases with a ratio between 1.8 and 2.2 were reviewed and wider areas recounted to confirm their status as amplified or not amplified.

Statistical Analysis

The association between HER2 status and clinical and biological characteristics was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Age differences were compared using the t test for independent samples. The two-sided significance level was set at p less than 0.05. Overall survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients were followed from date of diagnosis of Stage IIIb/IV disease to date of death or last follow-up. Survival data were obtained through medical records and the Social Security Death Index and were updated as of November 2011. Group comparisons were performed using the log-rank test.

RESULTS

Initial screening

A total of 1478 ADC were screened under the clinical assays and Sequenom mass spectrometry based genotyping assays. Of these, 894 (60%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 58–63%) were mutation positive (non-HER2) with a distribution as outlined in supplemental table 2. Among the remaining 584 “point mutation-negative” samples, 437 were tested by FISH for ALK rearrangements; 36 cases (8%) were positive (36/437, 95% CI 6–11%).

HER2 mutations

Five hundred and sixty (560) ADC samples that were negative for the predominant activating EGFR and KRAS mutations were tested for HER2 insertions. This group included 80 cases with point mutations detected by the extended Sequenom panel, 26 cases with ALK rearrangement, and 454 samples with no mutations. Ninety four cases (out of the above 584 “point mutation-negative” samples) could not be tested further due to insufficient DNA.

Among the 560 ADCs tested, we detected 26 HER2 mutations in 25 cases (5%, 25/560, 95% CI 3–7%). All mutations were mutually exclusive with point mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, MEK1 and AKT mutations as well as ALK rearrangements. An additional 53 EGFR and KRAS mutations were detected with Sequenom testing, therefore the HER2 mutation rate among ADC negative for both major and minor EGFR and KRAS mutations was 5% (26/507, 95% CI 3–7%). The incidence among the group negative for EGFR, KRAS, and ALK was 6% (20/335, 95% CI 3–8%). No HER2 mutations were identified among 104 squamous cell carcinomas and 6 small cell carcinomas tested.

Testing of a separate set of adenocarcinomas with a known positive mutation profile (n=330, 80 EGFR ex 19 del, 79 L858R, 120 KRAS G12&G13, 7 NRAS, 3 MAPK, 2 AKT, 30 BRAF) confirmed the mutually exclusive nature of HER2 exon 20 insertions with these mutations.

The vast majority of HER2 mutations, 92% (24/26), were in-frame insertions in exon 20 which ranged from 3 to 12bp, all nested in the most proximal region of the exon, between codons 775 and 881 (Figure 1). The 12bp insertion was the most common mutation (83%, 20/24) with all cases showing a duplication / insertion of 4 amino acids (YVMA) at codon 775. The 3bp insertion was the second most common (8%), 2/24) and was characterized as a complex insertion-substitution G776>VC by Sanger sequencing in the 2 identified cases. Two point mutations were also detected, L755S and G776C, corresponding to 8% (2/26) of all HER2 mutations identified. The G776C mutation was found concurrently with the HER2 V777_G778insCG. Figure 3

Figure 1. Summary of ERBB2 / HER2 mutations identified in the current study (26 mutations, 25 patients).

(2A) Schematic organization of ERBB2 kinase domain and detailed structure of the proximal region of Exon 20. Open black arrows flank the beginning and the end of exon 20. Solid black arrows mark the specific locations of the identified mutations. Mutation hotspot is demarcated by the box. 2B. Spectrum of mutations - Detailed description of all mutations identified. Insertion sequences are demarcated by the box; Black cross marks the point mutations.

Figure 3. Representative case harboring the most common ERBB2 mutation.

A775_G776insYVMA. (3A) Morphologically, this tumor showed a mixed phenotype with papillary, micropapillary and solid components. (3B) Standard sequencing (reverse) shows further characterization of the mutation as A775_G776insYVMA (2325_2336ins12 [ATACGTGATGGC]), bottom tracing. The arrow marks the beginning of the insertion sequence. Top tracing demonstrates the reverse WT sequence for comparison (3C) ABI tracing of the sizing assay shows a heterozygous 12bp insertion (arrow); asterisk marks the adjacent wild-type peak (*). This case was concurrently tested for indels in exon 19 and 20 of EGFR using a multiplex assay and illustrates the mutually exclusive nature of these mutations.

Clinical characteristics of patients with HER2 mutations

Comparison of HER2 mutants with the HER2 wild-type (WT) group

The clinical characteristics of patients with HER2 mutations are summarized in Table 1. After establishing the mutually exclusivity of HER2 mutations with other driver gene mutations, we defined a HER2 WT comparison group by combining all cases confirmed HER2 negative by testing with all cases harboring a mutation in any other gene. This group of 1359 cases is specified in Table 1 as the HER2 WT group. Comparison to this group shows the patients with HER2 mutations presented at a slightly younger age, with a median age of 64 years versus 66 years. The proportion of HER2 mutant patients presenting at age 64 or younger (64%) was greater than that of the HER2 WT population (46%, p=0.04). Significantly more never-smokers harbored HER2 mutations (5% vs. 1%, p<0.0001) but there were no significant differences in sex ratios (female 2% vs male 2%, p=0.83) or in the stage at presentation. HER2 mutations were not significantly more common among Asian patients (2/59, 3%) vs Caucasian patients (23/1267, 2%) (p=0.31).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of HER2 mutant patients vs other molecularly defined subsets

| HER2 (n=25) | HER2 WT (n=1359) | EGFR (n=359) | KRAS (n=495) | EML4-ALK (n=35) | BRAF (n=25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | (female/male) | 17/8 | 862/497 | 260/99 | 326/169 | 19/16 | 17/8 |

| Median age | (range) | 64 (51–84) | 66 (32–90) | 66(32–90) | 67 (38–86) | 56 (39–78) | 70 (54–79) |

| pts <64 / ≥66 yrs | 16/9 | 588/771(p=0.04) | 158/201 | 205/290 (p=0.04) | 21/14 | 12/13 | |

| Smoking Status | (never/smoker) | 17/8 | 340/1019 (p<0.0001) | 192/167 | 30/465 (p<0.0001) | 21/14 | 3/22 (p=0.0001) |

| Stage | (I–II / III–IV) | 15 / 10 | 631/728 | 147 / 212 | 246 / 249 | 7/28 (p=0.0025) | 11/14 (p=0.03) |

| Ethnicity | Asian /Caucasian | 2/23 | 59/1267 |

p values in parentheses based on comparison with HER; only significant values are annotated

Comparison of HER2 mutants vs. specific molecular subsets

When the HER2 WT group is stratified into molecular subsets (Table 1), we find that the younger age association is lost with most groups but remains significant only when compared to the cohort with KRAS mutations (p=0.04). Significant differences were identified in the smoking status of HER2-positive patients when compared to both KRAS and BRAF (p<0.0001). Similar smoking differences were observed when HER2 mutated patients were compared to the EGFR/KRAS/ALK negative and the negative for all mutations assayed groups (p<0.0001). In contrast, no significant differences in smoking were identified between the HER2-mutated and the EGFR-mutated groups. The stratification by molecular subtype also uncovered differences in the stage at presentation of the HER2 mutated group compared to both ALK-rearranged and BRAF-mutated cohorts, the latter two being associated with later stage (III–IV) presentation (p=0.003 and 0.03, respectively).

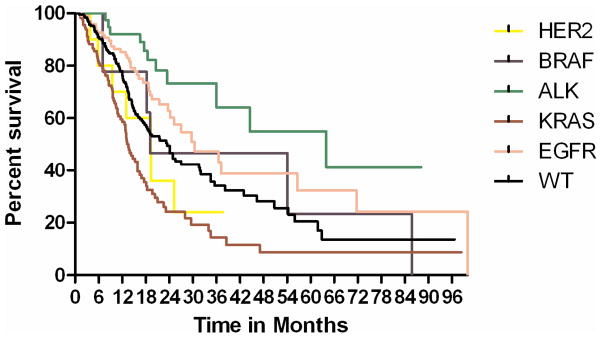

Clinical Outcomes (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival in patients with advanced stage (IIIB/IV) disease. The overall survival of the HER2 cohort was not statistically different from the other molecularly defined cohorts.

Due to the small sizes of stage- and mutation-specific cohorts, only overall survival was assessed. During follow-up, 468 patients presented with or developed advanced disease (stage IIIb or IV). This included 102 EGFR, 117 KRAS, 28 ALK, 10 BRAF, and 16 HER2 patients. The median follow-up after the diagnosis of advanced disease for all patients was 19 months. The median overall survival by molecular cohort was: HER2 19 months, EGFR 30 months, KRAS 14 months, ALK 25 months, and BRAF 21 months. In this series, the overall survival of the HER2 cohort did not differ significantly from the other molecularly defined cohorts.

Morphologic spectrum of HER2 mutant lung adenocarcinomas (Figure 3)

The vast majority of tumors harboring HER2 mutations (92%, 23/25) were moderate (11) to poorly (12) differentiated and most (80%, 20/25) had high grade morphology. Eighty percent (80%, 20/25) were tumors of mixed phenotype with papillary, acinar, solid and micropapillary, components as the most predominant patterns. Three cases had a mucinous component. A bronchoalveolar component was present in 6 tumors but it was minimal in most cases (67%, 4/6). Only 3 tumors showed a pure phenotype (1 papillary, 1 micropapillary, 1 solid) but all were small samples and may reflect limited sampling. Two cases were classified as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, NOS due to limited sampling, both with high grade cytologic features.

HER2 gene copy alterations by FISH (Table 2)

Table 2.

HER2 copy number alterations in HER2 mutant tumors

| HER2 copy number alterations | HER2 mutant (n=11) | HER2 WT (n=39) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplified | 0 | 1 (3%) | NS |

| High polysomy | 2 (18%) | 4 (10%) | NS (p=0.29) |

| Low polysomy | 8 (73%) | 27(69%) | NS |

| Disomy (or near disomy) | 1 (9%) | 7 (18%) | NS |

Analysis for HER2 gene copy number alterations by FISH was performed on 11 of the 25 HER2 mutated cases based on tissue availability and in 39 HER2 WT cases. None of the mutant cases showed HER2 amplification. Instead, 2 cases (18%) showed high polysomy (>4 copies of both HER2 and CEP17) and 8 (73%) had low polysomy. Among the WT group, one case was amplified (3%, 1/39) with a HER2/ CEP17 ratio of 5.9). In this group, 4 cases (10%) had high polysomy and 27 (69%) had low polysomy. Of note, the HER2 amplified case was also found to harbor an EGFR exon 19 deletion.

DISCUSSION

The management of lung adenocarcinomas has been transformed in the past decade by the identification of key genetic alterations that activate driver oncogenes. These alterations allow the assignment of patients to targeted treatments based on the specific molecular lesions detected in their tumors.

Mutations in the HER2 gene identify a distinct subset of lung adenocarcinomas. Although less common than EGFR and KRAS, these mutations represent an additional target with already proven sensitivity to HER2 inhibitors in preclinical models (23–25, 39) and anecdotal clinical reports (35, 40). Both trastuzumab and lapatinib are available and newer agents, such as dacomitinib and afatinib, are in clinical trials specifically for this indication (39, 41, 42). Given the high prevalence of lung adenocarcinomas, the targeting these mutations could benefit thousands of patients each year in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic implications of HER2 mutated lung adenocarcinoma remain poorly defined. Previous studies report attributes that parallel those seen with EGFR mutations, including associations with female sex, Asian ethnicity, never-smoker status, and adenocarcinoma subtype. Most studies, however, have been conducted in Asia. Only 2 studies have included Caucasian patients, a single study of 157 US patients in whom no mutations were detected (20), and a study of 402 European patients in which a mutation rate of 2% was identified (17). To our knowledge, our study represents largest assessment for HER2 mutations in a predominantly Caucasian population and the most comprehensive analysis for other mutations in the same cohort.

As HER2 mutations have been previously shown to be mutually exclusive with major mutations in EGFR and KRAS, we selected this negative group as our target for testing, allowing us to enrich for mutant cases. In this subset, we identified 25 HER2-positive cases, all mutually exclusive with other recurrent point mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA, MEK1 and AKT, as well as ALK rearrangements. Additional testing of a separate set of cases known to be positive for major EGFR and KRAS, further confirmed the mutually exclusive nature of these mutations. The incidence of HER2 mutations was 5 and 6% among the EGFR/KRAS negative and the EGFR/KRAS/ALK negative groups, respectively. Based on these mutually exclusive relationships, the proportion of tumors negative for EGFR, KRAS, and ALK, and the prevalence of HER2 mutations in the latter group, we estimate the overall prevalence in the entire group (1478 patients) to be approximately 2%, which is similar to that observed by Buttita et al (17), in their smaller study of European patients.

Among patients with HER2 mutations, insertions in exon 20 represented the vast majority of the alterations detected (96%, 24/25 patients). As a group, these mutations resemble activating mutations found within exon 20 of EGFR (non-T790M) which have been associated with primary resistance to both first and second generation TKIs (43). In both cases, insertions are in-frame, ranging from 3 to 12 base pairs and confined to a short stretch within the most proximal region of the exon (between the 7th and the 12th codon of the exon). Compared to EGFR, HER2 insertions are less heterogeneous, with over 80% of cases showing the A775_G776insYVMA insertion/duplication (figure 4). Two of the mutations detected in our series, have not been reported in previous studies (V777_G778insCG and G776C). The significance of the G776C mutation found concurrently with a 6 bp insertion is unknown.

Figure 4.

Positions of the HER2 exon 20 insertions identified in the present study and comparison with the spectrum of EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations identified at our institution over a 3 year period. Insertions in HER2 show significantly less heterogeneity compared to EGFR with over 80% of HER2 alterations being represented by the A775_G776insYVMA.

Having confirmed the mutually exclusive nature of HER2 mutations with other driver oncogenes, we then compared the clinical characteristics of HER2 positive patients with the WT group (cases confirmed HER2-negative by testing plus cases with mutations in another gene). In agreement with other groups (17, 20, 44), we found a significant association with never-smoker status (p<0.0001). In contrast, we did not identify a significant difference by sex or race, although the low number of Asian patients (59) limited the power of this analysis. Patients with HER2 mutations presented at a slightly younger age compared to the overall HER2 WT group and patients with KRAS mutations. While we noted differences in stage at presentation between the HER2 and both the BRAF and ALK subsets, this is difficult to explain biologically and of unclear clinical significance. In this cohort of patients with HER2-mutated lung cancers, survival was numerically similar to other molecularly-defined cohorts.

Previous studies have shown that HER2 mutations are confined to the adenocarcinoma subtype of NSCLCs but specific histologic subtype associations have only been assessed by a single group (17). In this study, Buttita et al reported that HER2 mutations are significantly more frequent in ADC with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma features.(45) In our study, we do not find this association. Instead we observe significant heterogeneity and a predominance of high grade morphologic features. Most tumors (82%) were of mixed phenotype with papillary, acinar, solid and micropapillary patterns representing the most common components, in decreasing order. The vast majority of tumors (92%) were moderately or poorly differentiated, as also reported in an Asian cohort (28).

In our analysis of HER2 copy number status, we did not find an association of HER2 mutations and gene amplification. While copy number gains were present in most of the cases studied, either as high or low polysomy, this finding was also present among the WT group without significant differences. Although the number of samples studied is small, this suggests that the presence of a HER2 mutation does not necessarily drive copy number gains of the mutated allele. By comparison, a recent study by Li et al reports a significant association with 7 of 8 mutant tumors showing HER2 gains (4 amplification and 3 high polysomy). While copy number variations in their WT group was not reported, previous studies in unselected patients report the presence of HER2 gene amplification by FISH in up to 23% of unselected NSCLC cases (14, 37, 38), suggesting that both amplification and high copy number gains can be present in a significant proportion of cases in the absence of mutations. Although discrepancies could be attributed to the limited number of cases, the combined findings would seem to suggest that, similar to what has been found in EGFR-mutated lung cancer, amplification cannot serve as a surrogate marker for activating HER2 mutations.

In summary, mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of HER2 identify a distinct subset of lung adenocarcinomas with a higher prevalence among never smokers. HER2 mutations are mutually exclusive with other activating mutations and independent of HER2 gene amplification. Given the high incidence of lung adenocarcinomas, there may be several thousand patients with this uncommon yet important mutation diagnosed every year in the United States, and their identification will allow for assignment to one of many investigational agents targeting this pathway. Testing for activating HER2 kinase domain aberrations, both point mutations and exon 20 insertions, should therefore be incorporated into standard multiplex molecular screening in lung adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The incidence, clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic implications of activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of HER2 in lung adenocarcinomas (ADCs) are not well established.

The current study represents the largest assessment for HER2 mutations (n=1478) in a predominantly Caucasian population and the most comprehensive concurrent analysis for other recurrent oncogene mutations. We show that mutations in HER2 identify a distinct subset of lung ADCs with highest prevalence among never smokers (5%) and which are mutually exclusive with other known driver oncogene mutations, making up 6% of lung ADCs lacking EGFR, KRAS, and ALK alterations.

Given the high incidence of lung ADC, it is estimated that there are between 1,000 and 2,000 patients with HER2 mutated lung ADC diagnosed every year in the United States and their identification would allow for assignment to one of many investigational agents targeting this pathway.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH: P01 CA129243 (to M.L., M.G.K.)

The authors thank Dr. Laetitia Borsu and Angela Marchetti for assistance with the Sequenom assays; Talia Mitchell, Justyna Sadowska and Jacklyn Casanova for technical assistance with EGFR and KRAS assays and Edyta B. Brzostowski for help with the MSKCC Lung Cancer Mutation Analysis Project database.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none to disclose

REFFERENCES

- 1.Daly JM, Jannot CB, Beerli RR, Graus-Porta D, Maurer FG, Hynes NE. Neu differentiation factor induces ErbB2 down-regulation and apoptosis of ErbB2-overexpressing breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3804–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Hynes NE. Single-chain antibody-mediated intracellular retention of ErbB-2 impairs Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1182–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riese DJ, 2nd, Stern DF. Specificity within the EGF family/ErbB receptor family signaling network. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 1998;20:41–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199801)20:1<41::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, Levkowitz G, Alroy I, Klapper L, et al. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. Embo J. 1996;15:2452–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzahar E, Waterman H, Chen X, Levkowitz G, Karunagaran D, Lavi S, et al. A hierarchical network of interreceptor interactions determines signal transduction by Neu differentiation factor/neuregulin and epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5276–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klapper LN, Glathe S, Vaisman N, Hynes NE, Andrews GC, Sela M, et al. The ErbB-2/HER2 oncoprotein of human carcinomas may function solely as a shared coreceptor for multiple stroma-derived growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4995–5000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–12. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gravalos C, Jimeno A. HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1523–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slomovitz BM, Broaddus RR, Burke TW, Sneige N, Soliman PT, Wu W, et al. Her-2/neu overexpression and amplification in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3126–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer CJ, Stephenson P, Thor A, Vangel M, Johnson DH. Trastuzumab in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: is there a role? Focus on Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study 2598. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1180–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellegrini C, Falleni M, Marchetti A, Cassani B, Miozzo M, Buttitta F, et al. HER-2/Neu alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive evaluation by real time reverse transcription-PCR, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3645–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA, Veve R, Chen L, Helfrich B, et al. Evaluation of HER-2/neu gene amplification and protein expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1449–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatzemeier U, Groth G, Butts C, Van Zandwijk N, Shepherd F, Ardizzoni A, et al. Randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine-cisplatin with or without trastuzumab in HER2-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:19–27. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buttitta F, Barassi F, Fresu G, Felicioni L, Chella A, Paolizzi D, et al. Mutational analysis of the HER2 gene in lung tumors from Caucasian patients: mutations are mainly present in adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2586–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies H, Hunter C, Smith R, Stephens P, Greenman C, Bignell G, et al. Somatic mutations of the protein kinase gene family in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7591–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki H, Shimizu S, Endo K, Takada M, Kawahara M, Tanaka H, et al. EGFR and erbB2 mutation status in Japanese lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:180–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shigematsu H, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Majmudar K, Suzuki M, Lee H, et al. Somatic mutations of the HER2 kinase domain in lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1642–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonobe M, Manabe T, Wada H, Tanaka F. Lung adenocarcinoma harboring mutations in the ERBB2 kinase domain. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:351–6. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephens P, Hunter C, Bignell G, Edkins S, Davies H, Teague J, et al. Lung cancer: intragenic ERBB2 kinase mutations in tumours. Nature. 2004;431:525–6. doi: 10.1038/431525b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang SE, Narasanna A, Perez-Torres M, Xiang B, Wu FY, Yang S, et al. HER2 kinase domain mutation results in constitutive phosphorylation and activation of HER2 and EGFR and resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perera SA, Li D, Shimamura T, Raso MG, Ji H, Chen L, et al. HER2YVMA drives rapid development of adenosquamous lung tumors in mice that are sensitive to BIBW2992 and rapamycin combination therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808930106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimamura T, Ji H, Minami Y, Thomas RK, Lowell AM, Shah K, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer and Ba/F3 transformed cells harboring the ERBB2 G776insV_G/C mutation are sensitive to the dual-specific epidermal growth factor receptor and ERBB2 inhibitor HKI-272. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6487–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Fujii A, Ohya J, Amano Y, Kitano Y, Abe D, et al. Pharmacological characterization of MP-412 (AV-412), a dual epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1977–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki T, Fujii A, Ohya J, Nakamura H, Fujita F, Koike M, et al. Antitumor activity of a dual epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB2 kinase inhibitor MP-412 (AV-412) in mouse xenograft models. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1526–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Sun Y, Fang R, Han X, Luo X, Wang R, et al. Lung Adenocarcinomas with HER2-Activating Mutations Are Associated with Distinct Clinical Features and HER2/EGFR Copy Number Gains. J Thorac Oncol. 7:85–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318234f0a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takano T, Ohe Y, Sakamoto H, Tsuta K, Matsuno Y, Tateishi U, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and increased copy numbers predict gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6829–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan Q, Pao W, Ladanyi M. Rapid polymerase chain reaction-based detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:396–403. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Y, Ren Y, Fang Z, Li C, Fang R, Gao B, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma from East Asian never-smokers is a disease largely defined by targetable oncogenic mutant kinases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4616–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arcila M, Lau C, Nafa K, Ladanyi M. Detection of KRAS and BRAF mutations in colorectal carcinoma roles for high-sensitivity locked nucleic acid-PCR sequencing and broad-spectrum mass spectrometry genotyping. J Mol Diagn. 13:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28 (Suppl 1):S24–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaft JE, Arcila ME, Paik PK, Lau C, Riely GJ, Pietanza MC, et al. Coexistence of PIK3CA and other oncogene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma - rationale for comprehensive mutation profiling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Greve J, Teugels E, Geers C, Decoster L, Galdermans D, De Mey J, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib (BIBW 2992) in patients with lung adenocarcinoma with mutations in the kinase domain of HER2/neu. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su Z, Dias-Santagata D, Duke M, Hutchinson K, Lin YL, Borger DR, et al. A platform for rapid detection of multiple oncogenic mutations with relevance to targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cappuzzo F, Varella-Garcia M, Shigematsu H, Domenichini I, Bartolini S, Ceresoli GL, et al. Increased HER2 gene copy number is associated with response to gefitinib therapy in epidermal growth factor receptor-positive non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5007–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, McCoy J, West H, Xavier AC, Gumerlock P, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization associates with increased sensitivity to gefitinib in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtypes: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6838–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale CM, Lifshits E, Gonzales AJ, Shimamura T, et al. PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11924–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cappuzzo F, Bemis L, Varella-Garcia M. HER2 mutation and response to trastuzumab therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2619–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross HJ, Blumenschein GR, Jr, Aisner J, Damjanov N, Dowlati A, Garst J, et al. Randomized phase II multicenter trial of two schedules of lapatinib as first- or second-line monotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 16:1938–49. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yap TA, Vidal L, Adam J, Stephens P, Spicer J, Shaw H, et al. Phase I trial of the irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor BIBW 2992 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 28:3965–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasuda H, Kobayashi S, Costa DB. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: preclinical data and clinical implications. The lancet oncology. 2012;13:e23–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cappuzzo F, Ligorio C, Janne PA, Toschi L, Rossi E, Trisolini R, et al. Prospective study of gefitinib in epidermal growth factor receptor fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive/phospho-Akt-positive or never smoker patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the ONCOBELL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2248–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomizawa K, Suda K, Onozato R, Kosaka T, Endoh H, Sekido Y, et al. Prognostic and predictive implications of HER2/ERBB2/neu gene mutations in lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 74:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.