Abstract

Joint attention between hearing children and their caregivers is typically achieved when the adult provides spoken, auditory linguistic input that relates to the child’s current visual focus of attention. Deaf children interacting through sign language must learn to continually switch visual attention between people and objects in order to achieve the classic joint attention characteristic of young hearing children. The current study investigated the mechanisms used by sign language dyads to achieve joint attention within a single modality. Four deaf children, ages 1;9 to 3;7, were observed during naturalistic interactions with their deaf mothers. The children engaged in frequent and meaningful gaze shifts, and were highly sensitive to a range of maternal cues. Children’s control of gaze in this sample was largely developed by age two. The gaze patterns observed in deaf children were not observed in a control group of hearing children, indicating that modality-specific patterns of joint attention behaviors emerge when the language of parent-infant interaction occurs in the visual mode.

The child’s ability to engage in joint attention with people and objects in the world is a fundamental cognitive process requiring perceptual, memory, categorization, and information processing abilities. Much research grounded in a social interactional framework (Tomasello, 1988) has shown that language input that is directly relevant to the child’s current focus of attention has a facilitative effect on language acquisition. This shared focus on objects and people, referred to as joint attention, is typically achieved when the caregiver provides spoken, auditory linguistic input about an object on which the infant is currently focusing visual attention. A radically different situation arises when the linguistic input co-occurs with the object of focus in the visual modality. Infants and caregivers interacting through sign languages such as American Sign Language (ASL) must also use the visual channel to perceive language. Their joint attention to objects and language occurs within a single modality, vision. Deaf children must have visual access to both the object and the interlocutor in order to temporally link linguistic input with the non-linguistic context. Understanding the nature and development of visual joint attention in this unique situation of language development is the goal of the current study.

From the earliest months of life, caregivers engage in face-to-face interactions with their infants, responding to their vocalizations, displaying positive affect, and speaking in a special register known as motherese, or child-directed speech (Fernald, 1992). In these early face-to-face interactions, infants gain experience with turn-taking and other discourse skills. As infants become increasingly mobile and begin to attend more to objects in the environment, interactions often involve the caregiver commenting on or labeling objects on which the infant’s attention is currently focused (Adamson & Chance, 1998). From this point forward, infants gradually take on a more active role in controlling the focus of attention, for example by pointing to an object and then checking their interaction partner’s gaze direction after pointing (Bretherton et al., 1981). This three-way coordination of attention between infant, caregiver, and objects is typically known as triadic or coordinated joint attention (Dunham & Moore, 1995), and it is during this type of interaction that language input is most closely linked to the child’s acquisition of new vocabulary (Tomasello & Farrar, 1986).

In signed languages such as ASL, all linguistic information is presented visually, through signs, facial expressions, and subtle body movements. Perceiving language in the visual mode poses a challenge to the typical developmental course of joint attention. Language cannot be perceived without visual attention to the interlocutor; however, if a child’s attention is drawn away from an object or event to which he or she is attending, the relationship between the linguistic input and the object may not be apparent. A system that is typically based on multimodal input must therefore adapt to a situation in which all input is uni-modal. Understanding how each partner’s behavior during dyadic interaction differs when all information is perceived through the visual mode can inform theories of development of joint attention across a range of situations revealing adaptive skills in both adults and children.

Prior work on interactions between deaf children and their caregivers has focused primarily on how the mothers adapt to interaction in the visual mode. For example, studies of interactions with young deaf infants have established that deaf mothers alter their sign language input in systematic ways using a unique register known as child-directed signing (Maestas y Moores, 1980; Harris, Clibbens, Chasin, & Tibbitts, 1989; Spencer, Bodner-Johnson, & Gutfreund, 1992; Swisher, 2000). Features of child-directed signing include a longer duration of individual signs (Masataka, 2000), greater cyclicity, duration, and size than signs in typical citation form, and more frequent sign repetition. In addition, deaf mothers tend to modify their own sign language input to make it accessible to their infants. They accomplish this using strategies such as touching the infant to attract attention, signing on the infant’s body, establishing eye gaze with their infant while signing, or displacing signs to produce them in the infant’s visual field (Holzrichter & Meier, 2000). Thus over the first year, deaf mothers make substantial modifications in their own sign language input to make their language both attractive and accessible to their children.

A few studies have also examined changes in maternal signing strategies that occur with development. Specifically, over the child’s second year, deaf parents have been found to use less explicit attention-getting strategies, and instead rely more upon the deaf child’s developing ability to interact in the visual mode (Harris et al., 1989). These less explicit strategies include waiting for the child to look up, or beginning to sign in conventional signing space with the expectation that the child will look up in response (Baker and van den Bogaerde, 1996; Waxman & Spencer, 1997). These strategies have been shown to be effective in achieving joint visual attention and are thought to foster linguistic development (Harris, 2001).

A further complication in studying deaf children’s joint attention is the fact that the vast majority are not exposed to language on a typical time course, due to the fact that approximately 95% of children are born to hearing parents who have no prior experience communicating through sign language (Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004). Deaf children with deaf parents have clear advantages over deaf children with hearing parents with regard to development of visual attention. First, deaf parents are experienced with the linguistic conventions and modality-specific discourse features that facilitate signed interaction (Koester, Papoušek, & Smith-Gray, 2000). In contrast, hearing parents often struggle to attract and maintain their deaf child’s attention long enough to provide meaningful linguistic input (Spencer & Lederberg, 1997), and as a result tend to be less successful at creating episodes of symbol-infused joint attention (Gale & Schick, 2009; Prezbindowski, Adamson, & Lederberg, 1998). Another advantage for deaf children with deaf parents is the fact that they have been socialized through interactions in which looking towards the caregiver is linked to rewarding linguistic input. Deaf children with hearing parents may be less likely to look up at their parents during play, because such looks have not been sufficiently reinforced over time and there may be little language visually available when they do look up (Waxman & Spencer, 1997).

Finally, deaf children with deaf parents have had more opportunities to learn about specific attention-getting behaviors and appropriate responses. For example, children must learn that a tap on the child’s body is a form of symbolic communication meant to direct attention to the interlocutor (Swisher, 2000). Deaf children with deaf parents have had greater opportunities to observe these signals not only on themselves but also as they are used by other family members. Thus in studies directly comparing deaf children with deaf vs. hearing mothers, children with deaf parents appear to have more finely developed visual attention skills. Chasin & Harris (2008) compared deaf children between the ages of 9 and 18 months, and found that children with deaf parents had more spontaneous looks to the mother at all ages than children with hearing parents, and that of those looks, a greater proportion were to the mother’s face. As a consequence of this looking behavior, deaf children with deaf mothers spend proportionately longer amounts of time in coordinated joint attention than the children with hearing mothers (Spencer, 2000). However the timing, frequency, and motivation behind deaf children’s spontaneous looks and other behaviors during parent-child interaction has not yet been systematically examined.

Among hearing children, one type of interaction that has received much study is joint book reading, due to the established links between the frequency and quality of caregiver-child book reading and children’s language and literacy outcomes (Bus, Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994). Joint book reading in deaf dyads presents a unique set of challenges requiring adaptation on the part of both the mother and the child. Beyond the demands of providing input that is relevant to the child’s attention, parents reading a book in sign language must also translate passages from the written text (e.g. English) to the particular sign language being used (e.g. ASL). Not surprisingly, deaf parents have been shown to use specific strategies to set up a visual literacy environment for their deaf children. For example, instead of signing in the normal signing space, deaf parents will often sign directly on the book, allowing the child to connect the pictured information with verbal information without having to shift gaze from the book to the adult signing (Lartz & Lestina, 1995). Parents may even use the book as part of the sign (Schleper, 1995). There is some evidence that, using this array of approaches to achieve joint attention and create an engaging interaction, joint book reading predicts linguistic skills in deaf children (Aram, Most, & Mayafit, 2006).

Despite the well-documented strategies used by deaf mothers, the way in which deaf children acquire the ability to interact in the visual mode remains largely undocumented. Studies have yet to reveal the types of skills that enable deaf children to engage in coordinated joint attention with their caregivers. That is, there is little understanding of how children adapt to the cognitive requirements of continuously alternating their own visual attention in order to achieve joint attention with their interlocutors. Harris et al. (1989) describe the development of an “attentional switching strategy,” but there is no clear account of when and how children develop such a strategy, and how this may fundamentally differ from the development of attention in the typical, bimodal situation of children who hear. The goal of the present study was to provide a detailed account of children’s development of joint attention in the single modality of vision. This study builds on previous work in two important ways. First, while earlier studies have focused only on maternal modifications and strategies, in the present study we conducted a micro-level analysis of children’s own gaze switching patterns. Second, while earlier research includes deaf children up to the age of two, the participants in the current study were between the ages of two and four. This allowed us to track development of joint attention after infancy and observe interactions at a time period in which children are typically acquiring and producing language at a rapid rate.

We investigated joint visual attention by analyzing deaf children’s gaze behavior during two types of dyadic interactions with their deaf mothers—a joint book reading interaction and an interaction centered around a set of toys. We chose book reading because it represents a complex and linguistically rich setting in which joint attention is crucial for a successful interaction. The toy interactions were included as a contrastive interaction so that we could determine whether the observed gaze patterns were specific to book reading or instead whether they would generalize across settings. We then compared deaf children’s gaze patterns to those of a control group of hearing children to determine which patterns of gaze are unique to joint attention in the visual mode. We hypothesized that there would be significant modality-specific behaviors in deaf children’s gaze patterns that would enable them to engage in joint attention episodes with their mothers. Beyond the adaptations that have been previously documented in deaf mothers, we predicted that the deaf children would make specific adaptations allowing them to coordinate and control their own visual attention from an early age. Finally, we sought to discover features of interactions among deaf dyads that might further our understanding of the resilience of the joint attention system in a range of situations.

Methods

Participants

Deaf Dyads

Deaf participants were recruited through direct contact with families in an early intervention program at a large school for the deaf. Four deaf children and their deaf mothers participated. The children in the dyads each had two deaf parents, were identified as deaf at birth, had hearing losses ranging from moderate to profound, and had at least one deaf sibling. All of the mothers reported that ASL was the primary language used in the home. All of the children also attended a center-based early intervention program in which ASL was the primary mode of instruction. Thus the children were immersed in ASL exposure both at home and in the classroom setting.

Hearing Dyads

A control group of hearing participants was obtained from the Providence Corpus (Demuth, Culbertson, & Alter, 2006) within the CHILDES database (MacWhinney, 2000). The Providence Corpus is a longitudinal corpus of spontaneous child-adult speech interactions of monolingual English speakers. The children in this corpus were videotaped during naturalistic and spontaneous interaction in their homes, and most were recorded for approximately one hour every two weeks, beginning with the onset of first words. One session from each of four different children was identified such that their ages could be matched as closely as possible to the deaf children in the present study. An additional requirement was that the videotaped interactions contain at least five minutes of continuous book reading where the parent was reading either a single book or a set of books to the child. Finally, in order to be included, the child’s eye gaze throughout the book reading session had to be easily observable from the videotape. Following these criteria, the final sample of hearing dyads was obtained. Demographic characteristics for all participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mother-Child Dyads

| Group | Dyad # | Child’s Gender | Age | Hearing Loss | Sibling Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaf | DD1 | F | 1;9 | Profound | One deaf brother (age 4 yrs) |

| DD2 | F | 2;1 | Moderate-Severe | Sibling of DD4 | |

| DD3 | F | 3;6 | Severe-Profound | Two deaf sisters (ages 7 yrs, 11 yrs) | |

| DD4 | M | 3;7 | Profound | Sibling of DD2 | |

| Hearing | HH1 | F | 1;10 | none | not available |

| HH2 | F | 1;11 | none | not available | |

| HH3 | M | 3;4 | none | not available | |

| HH4 | F | 3;6 | none | not available |

Data collection

Mother-Child Interaction

The deaf mothers and children were videotaped in their homes reading from a set of books and engaging in free play around a variety of toys and objects provided by the experimenter. In the book reading sessions, the mothers were instructed to read the books with their children as they typically would. The books were selected to match the general age-level and interests of the children, and included the following titles: Taking Care of Mom (Mayer & Mayer, 1993); Spot Goes to the Farm (Hill, 1987); and A Mother for Choco (Kasza, 1996). The toys were selected by the experimenter to engage the children’s interest and promote interaction between mother and child. The toys consisted of a picnic set, a school bus, a set of miniature figures, and a doll with feeding accessories. The mothers and children picked from the array of toys provided. The mother was instructed to play with each of the toys for as long as the child’s interest was maintained, at which point she would introduce the next toy.

In each session, two cameras were placed in the room to capture head-on views of both the mother and the child. The book reading sessions ranged from approximately 8 minutes to over 30 minutes, and the free play sessions ranged from approximately 15 to 30 minutes. The time was not controlled by the experimenter, but instead was determined by the amount of time that the child remained engaged in the activity. Although two of the participants were siblings (DD2 and DD4), they were filmed on separate occasions and did not participate in the interaction in which they were not the focus child.

Vocabulary measure

For three of the four deaf children, ASL vocabulary was assessed using the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Developmental Inventory for ASL (ASL-CDI; Anderson & Reilly, 2002). The ASL-CDI is a parent-report vocabulary checklist consisting of 537 signs in 20 semantic categories. One mother did not fill out the ASL-CDI.

Coding and Analysis

For the deaf dyads, a five-minute segment of book reading and a five-minute segment of free play were identified for each child from the videotapes. The book reading segments were obtained by identifying the onset of the first observed interaction around one of the provided books that lasted for at least five minutes. From this interaction, the first five minutes during which both the mother’s and child’s eyes and hands were clearly visible were extracted for analysis. The rationale for choosing a five minute sample was that this represented the length of time for which each dyad had at least one continuous interaction centered around books. This enabled comparison of the interactions across dyads and situations while keeping the time window constant.

To obtain the free play sample, the videotapes were reviewed to identify a sustained interaction that lasted for at least five minutes and centered around a single toy or set of toys. As with the book reading episodes, the first five-minute segment of sustained play during which both the mothers’ and child’s eyes and hands were clearly visible were extracted for coding.

For the hearing dyads, a five-minute segment of book reading was identified for each child from the videotaped interactions, beginning at the onset of reading in which the child’s gaze was clearly visible. Book reading was chosen as the comparative analysis for the hearing dyads as it was thought to represent a linguistically-rich joint attention interaction.

The identified segments were coded using the linguistic annotation system ELAN (the Eudico Linguistic Annotator; Crasborn, Sloetjes, Auer & Wittenburg, 2006). In the ELAN interface, transcription and coding are entered into a hierarchy of tiers, and annotations are time-linked to the video file. ELAN was used to complete a frame-by-frame analysis of each interaction. Linguistic information (ASL signs) was transcribed according to a modified version of the Berkeley Transcription System (Slobin et al., 2001). Eye gaze of both the mother and the child was then documented using frame-by-frame analysis of the digitized clips.

For the deaf mothers and children, all ASL signs were transcribed, and all accompanying non-linguistic activity (i.e. manual gestures, actions, and object manipulation) were coded by a deaf native-user of ASL or by a hearing, highly skilled user of ASL. In addition, the locus of the child’s gaze as well as all shifts in gaze were coded at each point in time. The locus of gaze was coded as partner, book/object, or away. Gaze to the partner refers specifically to looks to the interlocutor’s face, which is the typical locus of gaze for signers during comprehension (Emmorey, Thompson, & Colvin, 2009)1. Gaze to the object refers to looks to a picture in the book or to an object or toy. Gazes away included looks that were off-task, e.g. looks to the camera, the researcher, or to an unrelated object. Following these gaze categories, a gaze shift was coded as any shift in gaze from one locus to another. Using this coding scheme, a total of 618 gaze shifts were identified for the deaf children. For the mothers, all of the above categories were coded, as well as modified signs (i.e. signs that were produced outside the typical signing space) and attention-getters (i.e. taps and waves that are conventionally used in ASL interaction).

For the hearing dyads, the child’s locus of gaze and all gaze shifts were coded. Maternal gaze was not coded as the hearing-dyad interactions were used to compare child gaze patterns only.

Reliability

A portion of the interactions (roughly 25%) were coded by a second coder to determine inter-rater agreement. A portion of each dyad’s data was re-coded by selecting a random sample that represented approximately 25% of that dyad’s total data. Reliability scores were calculated as percent agreement (A/A+D). Percent agreement scores ranged from 82% to 96%. Any disagreements in coding were discussed until a consensus was reached. In cases where it was not possible to reach a consensus, the native signer’s codes were used. Percent agreement scores for specific analyses were: locus of child gaze: 87%; number of gaze shifts: 89%; modified signs: 96%; prompts for gaze shifts: 82%.

Results

Gaze Patterns

Mutual Gaze

To determine whether deaf mothers and children spent the majority of their dyadic interactions in mutual gaze, defined as mother and child directing gaze towards one another’s eyes, we analyzed gaze patterns. For each dyad, we computed the percent of total interaction time that was spent in mutual gaze for both the book and toy conditions, as well as the average duration of mutual gaze episodes. The percent of time spent in mutual gaze ranged from 4% to 39%, with a mean of 22% of total interaction time spent in mutual gaze. Individual episodes of mutual gaze were extremely short, lasting only 1.4 seconds on average (range .8 to 2.2 seconds). This suggests that parent-child interaction among deaf dyads is not primarily achieved through prolonged mutual gaze, and that other gaze patterns are employed. Similarly, in the toy condition, an average of 15% of interaction time was spent in mutual gaze (range 10% to 23%), and mutual gaze episodes lasted 1.3 seconds (range 1.1 to 1.5 seconds). There were no significant differences in the book vs. toy conditions with regard to either the amount of time spent in mutual gaze (Wilcoxon signed rank t-test, S = −3.0, p = .38), or the duration of mutual gaze episodes (S = 0, p = 1.0). The hearing dyads spent significantly less time in mutual gaze than the deaf dyads (Wilcoxon rank sum t-test, Z = −2.17, p = .03), with an average of only 1% of interaction time spent in mutual gaze (range 0% to 4%). Mean gaze duration for the hearing dyads was 0.9 seconds (range 0 to 1.8 seconds); the mean duration of mutual gaze episodes did not differ between the hearing and deaf dyads (Z = −.44, p = .66).

Locus of Gaze

Given that the majority of the five-minute interaction was not spent with mother and child looking directly at one another, we asked how gaze was allocated for each interaction partner in the dyad. Specifically, we measured the proportion of maternal and child gaze to either the interaction partner, the object (book or toy), or off-task, (i.e., to a non-related object or to a person other than the interaction partner). For maternal gaze during book reading, there was a fourth potential gaze direction, namely signing space. This refers to a particular gaze in which the mother looks in a specific direction, often straight ahead, as part of ASL discourse, with an accompanying non-manual marker and/or body shift to show character inflection or reported speech (Reilly, McIntire, & Anderson, 1994).

Analysis revealed that, although there was individual variation among the deaf dyads, on average both partners were on-task (i.e., looking at either the interlocutor or the joint focus of attention) over 90% of the time, see Table 2. During the book condition, maternal gaze was directed to the child 44% of the time on average, and to the book for 48% of the time. In the same condition, children’s gaze was directed to the mother 39% of the time, and to the book 54% of the time. In the toy condition, mothers looked at the toys 50% of the time, and the child 45% of the time. The children looked at their mother 27% of the time, and to the toys 69% of the time. Children’s proportion of gaze to the mother did not differ in book vs. toy conditions (Wilcoxon signed rank, S = 4.0, p = .25). In striking contrast, the hearing children spent on average only 1% of the time looking at their mother, 86% of the time looking at the book, and the remaining 12% of the time off-task (i.e., looking away). Deaf children looked to the mother for a significantly greater proportion of the time than did hearing children (Wilcoxon rank sum test, Z = −2.17, p = .03).

Table 2.

Locus of Gaze by Interaction Partner and Condition Across Five-Minute Interaction

| Group | Partner | Condition | Gaze to partner1 | Gaze to object | Gaze away | Gaze to signing space |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaf | Mother | Books | .44 (.23) | .48 (.19) | .03 (.04) | .05 (.06) |

| Mother | Toys | .50 (.14) | .45 (11) | .05 (.06) | n/a | |

| Child | Books | .39 (.22) | .54 (.23) | .07 (.06) | n/a | |

| Child | Toys | .27 (.06) | .69 (.09) | .04 (.04) | n/a | |

| Hearing | Child | Books | .01 (.02) | .86 (.18) | .12 (.18) | n/a |

mean proportion of time (standard deviation)

Gaze Shifts and Duration

Next we asked how the children attended to both the mother and the book simultaneously. We calculated the total frequency of gaze shifts, including those from the book or toy to the interaction partner and those from the partner to the book or toy. Gaze shifts “away,” defined as those shifts to or from other objects or people in the room were not included, as those shifts were considered off-task. In addition, as a measure of sustained attention, the duration of each gaze to the book or toy and the mother was computed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean Gaze Duration by Location and Total Gaze Shifts by Child

| Dyad | Mean gaze duration to books/toys (secs) | Mean gaze duration to mother (secs) | Total gaze shifts between partner and object (in 5 mins) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Books | Toys | |||

| DD1 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 67 | 65 |

| DD2 | 8.0 | 1.8 | 36 | 57 |

| DD3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 112 | 99 |

| DD4 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 105 | 77 |

| Naima | 147.8 | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Violet | 23.1 | 2.1 | 12 | n/a |

| William | 56.5 | 0.8 | 4 | n/a |

| Lily | 4.5 | 1.3 | 4 | n/a |

Children’s gazes were generally very short, lasting on average 4.2 seconds to the book and 2.6 seconds to the mother (in the book condition). There were no significant differences in mean gaze duration to either the mother or object for the deaf dyads in book vs. toy conditions (Wilcoxon signed rank, S = 4.0, p = .25 for both mother and object). As expected, the hearing children had longer mean gazes to the book than deaf children, approaching significance (Wilcoxon rank sum, Z = 1.88, p = .06). Conversely, hearing children had shorter mean gaze duration to the mother than did the deaf children, although the differences were not significant (Z = −1.74, p = .08). Hearing children’s gazes to the book averaged 58.0 seconds long, while gazes to the mother averaged only 1.4 seconds long.

Analysis of gaze shifts by the deaf children revealed extremely frequent shifts between the object and the mother. In each five-minute interaction, deaf children shifted gaze approximately every three to eight seconds. The total number of gaze shifts in the five-minute interaction averaged 80 shifts (range 36 to 112 shifts) in the book condition, or approximately 16 gaze shifts per minute. The deaf children shifted gaze an average of 75 times (range 57 to 99 shifts) in the toy condition, or 15 gaze shifts per minute. As predicted, this pattern was unique to the deaf children. The hearing children shifted gaze only 5 times in the five minute interaction on average, or one gaze shift per minute, which was significantly less frequent than the deaf children (Wilcoxon rank sum t-test, Z = −2.18, p = .03). One hearing child never shifted gaze towards the mother during the interaction, and the other three shifted gaze 4–12 times throughout the entire episode. Thus, in the present sample frequent and rapid gaze shifting was a behavioral adaptation unique to deaf children who sign to achieve joint attention in the visual mode.

Developmental differences

The four deaf dyads represented two different ages; DD1 and DD2 were roughly 24 months, and DD3 and DD4 were roughly 42 months. Developmental trends, as indicated by contrasts between the younger and older dyads, were most apparent in the total number of gaze shifts during the book reading sessions. In the younger dyads, DD1 shifted gaze between the book and the mother 67 times, and DD2 shifted gaze 36 times in the five-minute interaction. In the older dyads by contrast, DD3 shifted gaze 112 times, and DD4 shifted gaze 105 times in five minutes. In the toy condition, there was a less pronounced but still sizeable age-related increase in gaze shifting: in the younger dyads DD1 shifted gaze 65 times and DD2 shifted gaze 57 times, while in the older dyads DD3 shifted gaze 99 times, and DD4 shifted gaze 77 times. Age effects were also observed in the percent of time off-task (i.e. looking away), which was higher for the two younger dyads (15% and 8%) than for the older dyads (6% and 1%), but only in the book reading condition. This suggests that the older children may have been more engaged during these interactions than the younger children. The number of gaze shifts by child also patterned with vocabulary score, although as all deaf children had been exposed to ASL from birth, age and vocabulary were closely related in this sample.

Maternal Scaffolding of Visual Attention

There were two broad ways in which the deaf mothers attempted to ensure that their signs were visible to the child. The first way was to modify signs by producing them outside of the typical signing space such that they were visible to the child. For example, the mothers occasionally signed on the book or near an object on which the child was currently focusing attention. Each of these modifications was coded. In the book condition, mothers modified an average of 8% of their utterances (range 3% to 15%) either by signing on or near the book, or by leaning in to sign in the child’s visual focus of attention. In the toy condition, mothers modified an average of 12% of their utterances (range 2% to 25%), again by signing on or near the toy, or in the child’s visual focus of attention. However in both conditions the majority of maternal utterances were produced in the conventional signing space. This meant that, in order to perceive maternal utterances, the child had to either maintain an existing focus on or shift gaze towards the mother.

The second way mothers made their signs visible was to elicit a gaze shift in the child using an overt or non-overt prompt. To identify these maternal prompts, the events and actions immediately preceding each gaze shift by the child were coded. These maternal behaviors were found to fall into three categories of behavior that served to adapt to the child’s current focus and/or prompt a gaze shift. The categories were as follows:

Physical prompts: attention-getters (e.g. a tap or a wave directed towards the child), or a point on or near the book.

Linguistic prompts: maternal utterance onset as a prompt to look up, or maternal end of utterance as a prompt to look down. In order to count as a linguistic prompt, the child’s gaze shift had to occur within the temporal space of one sign, i.e. the child looked up at or during the first sign in the mother’s utterance, or looked down at or within one sign following the end of her utterance.

Gaze-based prompts: maternal gaze shifts to or from the book or child that prompt the child to follow her gaze.

Gaze and linguistic prompts often occurred together, when the mother simultaneously began an utterance and looked up, or ended an utterance and looked down. These combinations were noted and coded as “Linguistic + Gaze” prompts.

In addition to child gaze shifts that were preceded by a maternal prompt, some gaze shifts were initiated by the child, such that the child’s gaze shift was either immediately preceded by, or co-occurred with, the child’s own sign or point, indicating the child’s desire to communicate with the mother. These were coded as “child-initiated” shifts. Finally, any child gaze shift that occurred spontaneously in the middle of a maternal utterance without any observable prompt or associated child action was coded as “no prompt.”

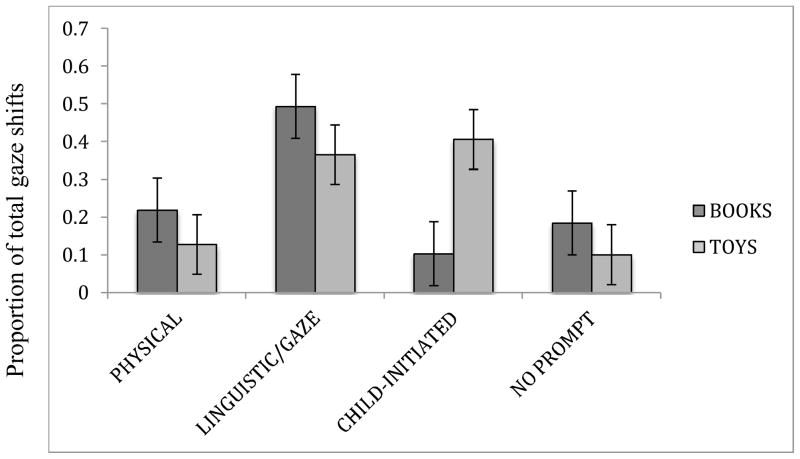

The distribution of the children’s gaze shifts were analyzed according to the type of maternal prompt (or lack thereof) that directly preceded them (see Figure 1). Gaze patterns in the book and toy conditions were highly similar, with one exception: in the book condition, only 10% of prompts were child-initiated, while in the toy condition, 41% of prompts were child-initiated. This is likely due to the fact that while in book reading, there was a clear maternal goal of getting from the beginning of the book to the end, during free play the activity was open-ended and typically driven by the child’s level of interest in a particular toy. Of the maternal prompts, a majority consisted of either the mother’s own gaze shift, an utterance onset or offset, or some combination therein. This category of prompt accounted for 49% of prompts in the book condition and 37% of prompts in the toy condition. In both conditions, there were more linguistic than physical prompts, although the difference was not significant (Wilcoxon signed rank, S = 5.0, p = .13). Thus, maternal prompts were most often congruent with conventional signing and involved little additional, overt behavior specifically intended to direct the child’s gaze.

Figure 1.

Gaze-shift prompt types used by the deaf dyads in the joint-attention conditions (books, n = 320; and toys, n = 298).

To further investigate the specific maternal behaviors that prompted the children to look at the mother in order to perceive her signing, we looked at the subset of child gaze shifts from the book to the mother. In the book condition, there were 165 gaze shifts that fell into this category. Across all four dyads, 18% were prompted by an attention-getter (i.e. a wave or a tap), 14% were prompted by the mother’s utterance onset, and 20% were prompted by a simultaneous maternal gaze up and an utterance onset. Only 8% of shifts were prompted by maternal gaze shift alone, and 3% were preceded by maternal contact with the book (i.e. pointing or turning the page). The remaining gaze shifts to the mother were either child-initiated (17%), or were not preceded by a prompt (19%). Thus, mothers were most effective in getting the child to look up at them when they tapped or waved at the child, or when the mother began a new utterance. In the toy condition, of the 144 gaze shifts to the mother, 24% were prompted by an attention-getter, 22% were prompted by an utterance onset, 42% were child-initiated, and 12% had no prompt. Maternal gaze shift alone was never a prompt for the child to look up, perhaps because it was too subtle to draw children’s attention away from the toys.

Maternal prompts to look up were also examined by individual dyad (Table 4). There were a few notable age-related differences. In the book condition, attention-getters (a highly overt prompt) comprised a higher proportion of prompts for the two younger children than for the two older children. In contrast, maternal gaze shift without an accompanying utterance onset (a highly subtle prompt) only resulted in a gaze shift for the two older children. However, when the mother lifted her hands to begin an utterance, with our without an accompanying gaze shift, both younger and older children responded to this prompt to look up at the mother, suggesting that the children understood that signs were about to be produced, and they looked up to perceive the input. Similarly, in the toy condition, the two younger children had a higher proportion of looks to the mother in response to an attention-getter than any other maternal prompt, while the two older children had a higher proportion of looks in response to a maternal utterance onset than any other prompt. Thus there were observable developmental differences in the types of prompts to which children responded, with an increase in responsiveness to subtle prompts (i.e. maternal gaze shifts) and linguistic cues (i.e. maternal utterance onset) in the older two children.

Table 4.

Number of maternal prompts (and proportion of total prompts) that preceded a gaze shift to the mother, by dyad and condition

| Condition | Dyad | Child-Initiated | No Prompt | Attn-getter | Point | Gaze only | Ling Only | Gaze & Ling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Books | DD1 | 10 (.29) | 4 (.12) | 9 (.26) | 0 | 0 | 5 (.15) | 6 (.18) |

| DD2 | 2 (.11) | 4 (.21) | 8 (.42) | 0 | 0 | 5 (.26) | 0 | |

| DD3 | 13 (.22) | 8 (.13) | 9 (.15) | 4 (.07) | 4 (.07) | 9 (.15) | 13 (.22) | |

| DD4 | 3 (.06) | 16 (.31) | 4 (.08) | 1 (.02) | 10 (.19) | 4 (.08) | 14 (.27) | |

| Toys | DD1 | 13 (.41) | 3 (.09) | 11 (.34) | 0 | 0 | 5 (.15) | 0 |

| DD2 | 9 (.32) | 7 (.25) | 9 (.32) | 0 | 0 | 3 (.11) | 0 | |

| DD3 | 29 (.62) | 2 (.04) | 5 (.11) | 0 | 0 | 11 (.23) | 0 | |

| DD4 | 11 (.30) | 5 (.14) | 9 (.24) | 0 | 0 | 12 (.32) | 0 |

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to determine how the development of joint attention, which is typically distributed across both auditory and visual channels, is adapted to a situation in which language and visual information is perceived within a single modality. We analyzed the gaze behavior of four deaf mother-deaf child dyads in two settings, comparing this to a control group of hearing mother-hearing child dyads. Significant modality-based differences in gaze behavior were found at every level of analysis. Deaf mothers and children spent more time gazing directly at one another’s faces than hearing dyads, although the majority of the interaction in both groups was not spent in mutual gaze. Whereas hearing children directed gaze almost entirely to the book, deaf children’s gaze was divided between the book or object and the mother. Deaf children gazed to the book in short bouts lasting only a few seconds, while hearing children maintained gaze to the book for a minute or longer. Most strikingly, deaf children shifted gaze between the mother and the book every few seconds throughout the interaction, whereas hearing children rarely shifted gaze. The deaf children’s gaze shifts were largely synchronized with specific maternal behaviors, ranging from overt, physical attention-getting devices, to more subtle prosodic and non-manual cues in the sign language stream. Gaze control was largely in place by the age of two, however there were important increases in the degree of sophistication of gaze shifting that occurred after this age. Below we discuss each of these findings with regard to how they might further our understanding of development of joint attention in deaf and hearing populations.

The first major finding of this study concerns the unique patterns of gaze observed in deaf children during dyadic interaction. In order to achieve the type of simultaneous attention to both linguistic and non-linguistic information that hearing children receive through two modalities, in a signed interaction both partners must carefully and continually monitor one another’s actions, and react to them by shifting gaze at appropriate times. In the joint book reading interactions observed, the hearing children could easily engage in joint attention by maintaining gaze to the book while perceiving auditory language input and rarely if ever looked towards their mothers. The deaf children could not employ the same strategy, as sustained gaze to the book would preclude receiving language input. While mutual gaze comprised a small proportion of the interaction among the deaf dyads, this was not an effective strategy to establish joint attention, as it would not allow the children to make visual connections with objects and pictures. Instead, coordinated joint attention was actively achieved by the children with frequent and carefully timed shifts to the mother and the book or toy. These gaze shifts enabled the child to perceive linguistic input and connect it to the non-linguistic context in a sequential but organized and dynamic fashion. Despite the small sample size of the current study, the findings were robust and consistent across dyads, and we speculate that similar behaviors would be observed in a larger group of deaf children. Thus it appears that joint attention can be achieved in the visual modality through a key adaptation in children’s gaze behavior that enables them to coordinate input with their caregivers.

The deaf children’s gaze shifts were meaningful in that they were largely executed in response to cues provided by their mothers. While maternal gaze shifts alone were rarely sufficient to prompt a child’s gaze shift, maternal utterance boundaries (with or without an accompanying gaze shift) did serve as an effective cue. Furthermore, the greater number of child gaze shifts that occurred at maternal utterance onset (i.e. with a prompt) relative to those that occurred mid maternal utterance (i.e. with no maternal prompt) suggests that children may have been learning to coordinate their gaze shifts with the timing of maternal linguistic input. This required knowledge of both the physical behavior that tends to precede a signed utterance (i.e. lifting the hands into signing position), as well as a cognitive awareness that meaningful linguistic information would be provided at that moment. The children also responded successfully to overt bids for attention, i.e. taps and waves, which suggests that children at this age had learned that these pragmatic devices in ASL are intended to direct attention to the mother (Swisher, 2000). This pattern of responses accords with the findings of Chasin & Harris (2008) in younger deaf dyads, in which children’s looks to the mother were increasingly executed in response to an elicited bid for attention between 9 and 18 months. The children studied here had clearly acquired this highly controlled, visual-perceptual ability through built-up experiences interpreting maternal linguistically-grounded prompts.

The second major finding of the present study is that children’s control of gaze appears to be largely in place by the age of two. The four children in the deaf dyads represented two ages, approximately two years and three-and-a-half years. Across all dyads, mothers produced the majority of signs in conventional signing space and only modified a small proportion of signs into the child’s existing focus of attention, which places the burden of attention shifting largely on the child. This suggests that by the age of two, children were already directing their own gaze and switching gaze between the focus of attention and the interlocutor in order to coordinate visual attention to objects and to language. This remarkable control exhibited by children as young as 21 months is likely due to the fact that in their early interactions, their deaf mothers provided visually accessible language, modeled appropriate attention-getting prompts, and supported the children’s development of these important skills (Harris et al., 1989; Spencer et al., 1992). The present results reveal that children who are exposed to this kind of visually embedded interaction develop a high degree of sensitivity to maternal linguistic and non-linguistic cues along with an ability to respond with precision to the dynamic demands of both a visual language and a visual environment.

Although the two younger children showed sophisticated gaze control, the behavior of the two older children suggests that there is continued development and refinement of children’s control of visual attention beyond the age of two. The two older children showed a marked increase in the number of meaningful gaze shifts between the book or toy and the mother, producing roughly twice the number of purposeful gaze shifts as the younger children. Thus in the developmental time span from 24 to 48 months, deaf children engaged in the interaction and controlled their own attention with increased sophistication. The younger children, while still shifting frequently, had more shifts away from the interaction, and were still learning when and how to optimally shift attention between the mother and the visual scene of joint attention. Furthermore, the two younger children had either the same number or fewer shifts during the book vs. toy conditions, while the two older children both shifted gaze more frequently during the book than the toy conditions. Joint book reading represents a complex type of visual interaction that is language-dependent. Thus the finding that the older children increased their gaze shifts in this language-laden situation provides further evidence that the cognitive skills that underlie joint attention co-develop with language. Finally, only the two older children appeared to be sensitive to the most subtle maternal cue of shifting her own gaze as a signal that input was forthcoming.

In the children studied here, age, vocabulary, and number of gaze shifts during both book and toy conditions were closely related. While age and vocabulary were confounded in the current sample, we hypothesize that this relationship would bear out in a larger group of deaf children with more diverse language experience. As deaf children learn to look between their interlocutors and visual scenes more effectively, they are likely to become better able to connect linguistic input in a meaningful way to the world around them. This is an important direction for future work, particularly in light of the diverse situations in which deaf children are first exposed to language.

The present findings highlight the ways in which children and adults engage in joint attention in a visual language in an environment where parents draw on their own abilities and experiences to support development in their children. This careful scaffolding appears to occur on a natural timeline that coincides with the child’s developing physical, cognitive, and linguistic skills. Mothers provide more overt and directive cues, such as touching the infant or actively obtaining their attention, during the first 9 to 12 months (Chasin & Harris, 2008). This is the same time period during which infants typically begin to engage in triadic visual attention with people and objects (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; Carpenter, Nagell, & Tomasello, 1998). By the time they are two years old, deaf children with deaf parents are able to effectively control their own gaze behavior in order to achieve optimal attention to both people and visual scenes, in a manner that is qualitatively different from behaviors observed in hearing children (Richmond-Welty & Siple, 1999). By this point, mothers do not make as many overt bids for attention, but rather sign in a conventional style while the child actively switches attention.

The ability to coordinate attention to both objects and people is a fundamental skill that develops over the first years of life, and paves the way for meaningful language exchange between caregivers and children. It has been hypothesized that deaf children will show delays in visual attention due to their lack of auditory input (Kelly et al.,1993; Smith, Quittner, Osberger, & Miyamoto, 1998). The results of the current study provide evidence that this is not the case. When exposed to accessible language input from birth, deaf children show no deficits in development of specific elements of visual attention (Spencer, 2000), namely the ability to monitor and respond to input from their interaction partners. We speculate that young deaf children with finely tuned control of visual joint attention exhibit precocious development, and this may even manifest as advantages in some cognitive domains in later adolescence and adulthood (Dye, Hauser, & Bavelier, 2009; Bélanger, Slattery, Mayberry, & Rayner, 2012). Further investigation of gaze control in a larger sample of deaf infants beginning at younger ages will help illuminate the origins and precursors to development of these specialized cognitive abilities.

The current results expand our understanding of how joint attention adapts to a unique situation in which all language input is perceived visually. While hearing infants perceive auditory language input while visually attending to objects and events, deaf infants achieve a parallel level of coordinated information through meaningful and frequent gaze shifts and through careful monitoring of adult cues. Although hearing children are certainly active participants in directing their own attention, deaf children appear to be particularly active in that they must execute an overt behavior, namely gaze shifting, in order to engage in coordinated joint attention. The ability of children to engage in complex gaze shifting may be necessary in order for deaf children to receive relevant language input. The fact that deaf children gaze shift so frequently and deftly at such a young age suggests that joint attention is a highly robust and resilient cognitive skill that adapts to a range of communicative and interactive settings.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the NSF Visual Language and Visual Learning Science of Learning Center (SBE 0541953), an NIDCD award to the first author (DC 011615), and the UCSD Division of Social Sciences. The authors thank Jenny Kan, Reyna Lindert, Katherine Demuth, and all the families who participated in this research. Portions of this work were presented at the Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD 35), November, 2010.

Footnotes

There was one exception to this, which occurred when a mother produced a classifier sign for STRIPES, in which she signed on her own foot to indicate that the character had striped feet. In this instance, the child looked down to the mother’s hands and not her face.

References

- Adamson LB, Chance S. Coordinating attention to people, objects, and symbols. In: Wetherby AM, Warren SF, Reichle J, editors. Transitions in prelinguistic communication: Preintentional to intentional and presymbolic to symbolic. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1998. pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Reilly J. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Normative Data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2002;7(2):83–119. doi: 10.1093/deafed/7.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aram D, Most T, Mayafit H. Contributions of mother-child storybook telling and joint writing to literacy development in kindergartners with hearing loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2006;37:209–223. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Adamson LB. Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant and peer-infant interaction. Child Development. 1984;55:1278–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AE, van den Bogaerde B. Language input and attentional behavior. In: Johnson Carolyn E, Gilbert John HV., editors. Children’s language. Vol. 9. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. pp. 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger NN, Slattery TJ, Mayberry RI, Rayner K. Skilled deaf readers have an enhanced perceptual span in reading. Psychological Science. 2012;23(7):816–823. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Bates E, McNew S, Shore C, Williamson C, Beeghly-Smith M. Comprehension and production of symbols in infancy. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:728–736. [Google Scholar]

- Bus A, Van Ijzendoorn M, Pellegrini A. Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research. 1995;65(5):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Nagell K, Tomasello M. Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for research in Child Development. 1998;63(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasin J, Harris M. The development of visual attention in deaf children in relation to mother’s hearing status. Polish Psychological Bulletin. 2008;39(10):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Crasborn O, Sloetjes H, Auer E, Wittenburg P. Combining video and numeric data in the analysis of sign languages with the ELAN annotation software. In: Vetoori C, editor. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign languages: Lexicographic matters and didactic scenarios. Paris: ELRA; 2006. pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth K, Culbertson J, Alter J. Word-minimality, epenthesis and coda licensing in the early acquisition of English. Language and Speech. 2006;49:137–174. doi: 10.1177/00238309060490020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham PJ, Moore C. Current themes in research on joint attention. In: Moore C, Dunham P, editors. Joint attention: Its origin and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dye M, Hauser P, Bavelier D. Is visual selective attention in deaf individuals enhanced or deficient? The case of the useful field of view. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Thompson R, Colvin R. Eye gaze during comprehension of American Sign Language by native and beginning signers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2009;14(2):237–243. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A. Meaningful melodies in mothers’ speech to infants. In: Papoušek H, Jurgens U, Papoušek M, editors. Nonverbal vocal communication: Comparative and developmental approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 262–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gale E, Schick B. Symbol-infused joint attention and language use in mothers with deaf and hearing toddlers. American Annals of the Deaf. 2009;153(5):484–503. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Clibbens J, Chasin J, Tibbitts R. The social context of early sign language development. First Language. 1989;9(25):81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. It’s all a matter of timing: sign visibility and sign reference in deaf and hearing mothers of 18-month-old deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2001;6(3):177–185. doi: 10.1093/deafed/6.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Eric. Spot Goes to the Farm. G. P. Putnam’s Sons; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Holzrichter AS, Meier RP. Child-directed signing in American Sign Language. In: Chamberlain C, Morford JP, Mayberry RI, editors. Language Acquisition by Eye. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kasza Keiko. A Mother for Choco. Puffin Books; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DP, Kelly BJ, Jones ML, Moulton NJ, Verhulst SJ, Bell SA. Attention deficits in children and adolescents with hearing loss. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1993;147:737–741. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160310039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester LS, Papoušek H, Smith-Gray S. Intuitive parenting, communication, and interaction with deaf infants. In: Spencer PE, Erting CJ, Marschark M, editors. The Deaf Child in the Family and at School. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lartz MN, Lestina LJ. Strategies deaf mothers use when reading to their young deaf or hard of hearing children. American Annals of the Deaf. 1995;140(4):358–362. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. 3. Vol. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. The Database. [Google Scholar]

- Maestas y Moores J. Early linguistic environment: Interactions of deaf parents with their infants. Sign Language Studies. 1980;26:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Masataka N. The role of modality and input in the earliest stage of language acquisition: Studies of Japanese Sign Language. In: Chamberlain C, Morford J, JP, Mayberry R, editors. Language acquisition by eye. Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G, Mayer M. Taking Care of Mom. Golden Books Publishing Company; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE, Karchmer MA. Chasing the mythical ten percent: parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing students in the U.S. Sign Language Stud. 2004;4:128–163. [Google Scholar]

- Prezbindowski AK, Adamson LB, Lederberg AR. Joint attention in deaf and hearing 22 month-old children and their hearing mother. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19(3):377–387. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly J, McIntire M, Anderson D. Look who’s talking! Point of view and character reference in mothers’ and children’s ASL narratives. Paper presented at the Boston Child Language Conference; Boston, MA. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond-Welty D, Siple P. Differentiating the use of gaze in bilingual-bimodal language acquisition. Journal of Child Language. 1999;26:321–328. doi: 10.1017/s0305000999003803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough H, Dobrich W. On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review. 1994;14(3):245–302. [Google Scholar]

- Schleper DR. Reading to deaf children: Learning from deaf adults. Perspectives in Education and Deafness. 1995;13(4):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Slobin DI, Hoiting N, Anthony M, Biederman Y, Kuntze M, Lindert R, Pyers J, Thumann H, Weinberg A. Sign language transcription at the level of meaning components: The Berkeley Transcription System (BTS) Sign Language & Linguistics. 2001;4(1/2):63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Quittner AL, Osberger JJ, Miyamoto R. Audition and visual attention: The developmental trajectory in deaf and hearing populations. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(5):840–850. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer PE. Looking without listening: Is audition a prerequisite for normal development of visual attention during infancy? Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2000;5(4):291–302. doi: 10.1093/deafed/5.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer PE, Bodner-Johnson BA, Gutfreund MK. Interacting with infants with a hearing loss: What can we learn from mothers who are deaf? Journal of Early Intervention. 1992;16(1):64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer PE, Lederberg A. Different modes, different models: Communication and language of young deaf children and their mothers. In: Adamson L, Romski M, editors. Communication and Language: Discoveries from atypical development. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1997. pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher V. Learning to converse: How deaf mothers support the development of attention and conversational skills in their young deaf children. In: Spencer P, Erting CJ, Marschark M, editors. The Deaf Child in the Family and at School. Mahwah, NH: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. The role of joint attentional processes in early language development. Language Sciences. 1988;10:69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Farrar MJ. Joint attention and early language. Child Development. 1986;57:1454–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman R, Spencer P. What mothers do to support infant visual attention: Sensitivities to age and hearing status. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 1997;2:104–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]