Abstract

The development of rapid, low cost, point-of-care approaches for the quantitative detection of antibodies would drastically impact global health by shortening the delay between sample collection and diagnosis, and by improving the penetration of modern diagnostics into the developing world. Unfortunately, however, current methods for the quantitative detection of antibodies, including ELISAs, western blots and fluorescence polarization assays, are complex, multiple step processes reliant on well-trained technicians working in well-equipped laboratories. In response we describe here a versatile, DNA-based electrochemical “switch” for the rapid, single-step measurement of specific antibodies directly in undiluted, whole blood at clinically relevant, low-nanomolar concentrations.

The development of rapid, low cost, point-of-care approaches for the quantitative detection of antibodies would drastically impact global health by allowing more frequent testing, narrowing the delay between diagnostic and treatment and improving the penetration of molecular diagnostics into the developing world1–3. The primary obstacle to achieving these ends, however, is that existing single-step methods for the quantitative detection of antibodies generally fail when deployed directly in complex clinical samples. For example, due to the confounding effects of non-specific adsorption to sensor surface, approaches that monitor adsorbed mass or in refractive index, such as microcantilevers and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), are not selective enough to work directly in undiluted blood serum, much less in whole blood4–6.

In response to the selectivity problem encountered by adsorption-based approaches, we and others have recently described electrochemical platforms that, in approximate analogy to fluorescence polarization assays7, detect antibody binding to a DNA-attached epitope8 (or to an epitope only9), which reduces the efficiency with which an attached redox reporter collides with -and thus exchanges electrons withan underlying electrode. The selectivity of this collision-based mechanism, however, is not perfect; while such sensors perform reasonably well in undiluted blood serum, they fail when challenged in undiluted whole blood10. Given that dilution requires operator intervention and, ultimately, reduces detection limits (by the dilution factor), it would be best to develop a signalin mechanism that is selective enough to transduce the presence of antibodies directly in whole blood, an effort that we explore here.

Inspired by the impressive selectivity of naturally occurring chemosensory systems, recent years have seen the emergence of a new class of synthetic biosensors that mimic nature by coupling target recognition with a robust structure-switching mechanism11–16. These typically employ nucleic acids or proteins re-engineered to undergo a large-scale, binding-induced conformational change that separates (or brings together) two reporter moieties to produce an optical or electrochemical output17–22. Of particular note, electrochemical “switch-based” sensors have proven selective enough to employ directly in complex clinical samples20. They are also rapid, reagentless, and easily multiplexed23. Motivated by these arguments, we have developed a versatile electrochemical switch that supports the rapid, quantitative detection of antibodies directly in whole blood at clinically relevant, low-nanomolar concentrations.

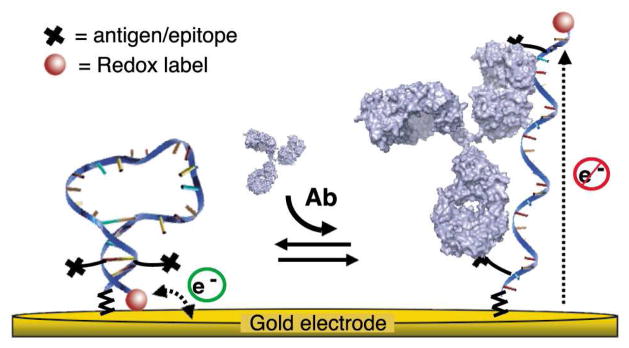

The design of our switch takes advantage of the two binding sites present on each antibody15, which are separated by ~12nm [ref24] (Figure 1). Specifically, we engineered the DNA switch such that it forms a stem-loop, placing the two antigens, epitopes or haptens (hereafter referred to as an “antigen” for simplicity), which are covalently linked in the middle of the two strands of the stem, in close proximity (< 4 nm) (Figure 1 and 2a). Upon binding of the antibody to one of these antigens the high effective concentration of the second antigen provides the driving force to open the switch and enable the more favorable bi-dentate binding25. Our motivation for using DNA as the scaffold for our switch is several fold. First, the chemistry of DNA supports the addition of a variety of antigens ranging from small molecules to polypeptides and proteins, either during its automated chemical synthesis or through post-synthesis conjugation26. Second, DNA-based switches are robust (i.e., are not triggered by nonspecific interactions), and relatively stable against degradation20,23. Finally the base-pairing code of DNA renders it easy to tune the switch’s thermodynamics so that the sensor achieves optimal detection limits27.

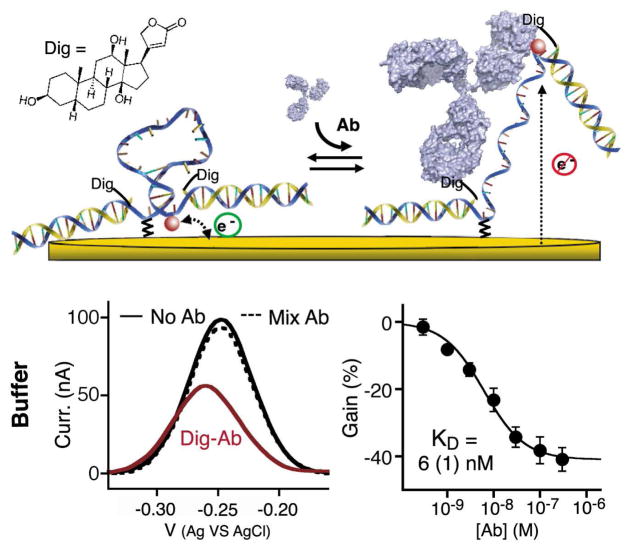

Figure 1.

An antibody (Ab)-activated electrochemical “switch” that uses a redox-modified DNA scaffold conjugated with two antigens or epitopes and specifically triggered by bi-dentate antibody binding. The switch is composed of a single stranded DNA probe containing two identical, covalently-linked antigens (black crosses) and modified at the two ends with a redox label (MB: methylene blue) and a thiol group for convenient attachment to a gold electrode surface. In absence of the target antibody, the DNA adopts a stem-loop conformation that brings the redox label near the gold electrode thus enabling rapid electron transfer. Upon binding of the relevant cognate antibody, the DNA probe opens, which brings the redox label far from the electrode thus resulting in lower electron transfer rate and Faradaic current. By coupling recognition to a large-scale conformational change this mechanism renders the sensor largely insensitive to the non-specific adsorption that takes place when the sensor is deployed directly in complex biological samples4–6.

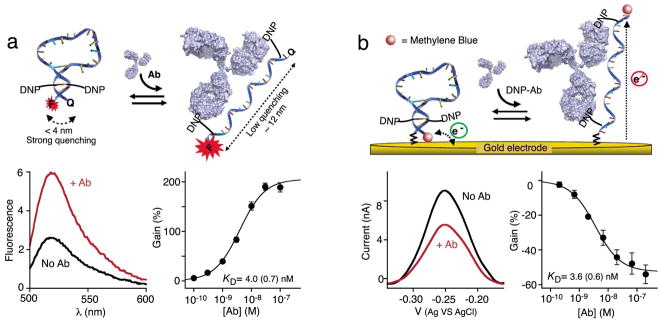

Figure 2.

As initial validation of the antibody-activated switch architecture we used the well-characterized hapten 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP)28, thus targeting anti-DNP antibodies (DNP-Ab). To do so we designed a tetra-modified DNA stem loop that contains two DNP moieties attached in the middle of the 5 base-pair double-stranded stem and a 18-base poly-thymine loop (~10 nm). The stability of the stem was “tuned” to slightly favor the closed state (switching equilibrium constant of ~ 0.5 –see Figure S1), as this represents the optimal trade off between low background (linked to higher stem stability) and high affinity (achieved at lower stem stability)27. Using either (a) fluorescent reporters (5′-FAM and 3′BHQ-1) or (b) an electrochemical readout (5′-C6-thiol group for attachment to the gold electrode and a 3′-methylene blue redox reporter), we observe robust responses to the addition of the sensor’s specific antibody target (~200% fluorescence gain and ~ 50% signal current reduction). Both sensors exhibit similar detection limits (0.3 nM and 0.6 nM respectively, at a coefficient of variation of 3). The titrations shown in this figure represent the average of measurements conducted with three sensors (independently fabricated in the case of the electrochemical sensor), with error bars reflecting the standard deviation.

As initial proof-of-principle validation of these new molecular switches we first fabricated and tested a switch employing the well-characterized hapten 2,4-dinitrophenol, DNP (thus targeting anti-DNP antibodies28), which can be easily conjugated to DNA during commercial chemical synthesis (Figure 2 and Materials and Methods). We designed the stem loop sequence to remain largely closed in the absence of the antibody but without being overly stabilized, which would harm affinity27 and possibly favor the binding of two antibodies to a single switch. As described previously, to optimize the detection limit of such switch sensors, a switching equilibrium constant of ~ 0.5 (66% closed) represents the optimal trade off between low background and high affinity27. We achieved this equilibrium constant by linking a stem containing four Watson-Crick base pairs and a T-T mismatch to an unstructured, 18-base poly-thymine loop (~ 10 nm) (Figure S1). This linker is long enough to span the ~12 nm between the two antigen binding sites on one antibody24 (the DNP linkers each providing an extra ~1.5nm) but short enough to ensure the cooperative binding of a single antibody to a single switch25.

For this “first-look” proof-of-principle we converted the above switch into an optically reporting sensor by modifying its two termini with fluorescein (FAM) and Black Hole Quencher (BHQ-1), a well-characterized Forster resonance energy transfer pair with a convenient, 5 nm Forster radius29. Consistent with its design principles, this optical switch responds in seconds to anti-DNP antibodies (Figure S2), producing a 3-fold increase in fluorescence at saturating target (Figure 2a) and achieving a sub-nanomolar detection limit (Figure 2a). Of note, this gain is lower than that seen for molecular beacons11, an analogous optical sensor for the detection of specific oligonucleotides; to ensure that one switch does not bind two antibodies simultaneously (remaining closed) we employ a low-stability stem than is optimal for molecular beacons, raising the background and reducing the observed gain. In support of the proposed sensing mechanism, the binding of anti-DNP antibodies to the switch is inhibited by free DNP (Figure S2).

While the fluorescent read-out described above is convenient for laboratory studies, the reduced equipment overhead of electrochemistry and its convenience for measurement directly in whole blood30 renders electrochemical- readouts better suited to point of care diagnostic applications20,23. To adapt antibody switches to this more promising mechanism we attached the DNA stem loop to a gold electrode by replacing the 5′-FAM with a 5′-C6-thiol group (which enables easy attachment via a the formation of sulfur self-assembled monolayer when co-deposited with 6- mercaptohexanol) and by replacing the 3′-BHQ-1 with the redox reporter methylene blue (Figure 2b). As expected, in absence of its target antibody the switch produces a significant Faradaic current. In the presence of saturating amount of anti-DNP antibody (30 nM), this current falls by ~50% within a few minutes (Figure 2b). The detection limit of this electrochemical switch displays similar subnanomolar detection limit than the optical switch suggesting that surface attachment does not significantly alter the binding-induced structural change taking place upon antibody binding31. Of note, this detection limit is well below clinically relevant antibody concentrations35,36.

A potential limitation of the switch architectures described above is that they require the synthesis of a tetra-modifed DNA strand (e.g., the two antigens, the anchor moiety and the redox label -or with fluorophore and quencher for the optical switch). In response, we have also designed a modular DNA switch that reduces the cost and complexity of synthesis by introducing the two antigens via the hybridization of two copies of a single, antigen-modified oligonucleotide (Figure 3, top). As a test bed for developing this modular design we used the well-characterized digoxigenin (Dig) hapten as our antigen (Figure 3). We find that the gain (~ 45%) and detection limit of this modular switch (~ 1 nM) compare closely to those of the tetra-modified DNA strand switch described above (Figure 2b). The modular switch is also highly specific, remaining “unactivated” even upon the addition of a 100-fold higher concentration of random human antibodies (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In order to simplify switch synthesis (i.e. to avoid the synthesis of a tetra-modified DNA probe), we have designed a modular architecture in which the two antigens are attached via the hybridization of two copies of a 17-base DNA strand (yellow strands) each modified only via the addition of the antigen (here the hapten digoxigenin, Dig). The modular stem-loop scaffold contains a frame inversion near one end to allow for symmetrical labeling of two copies of the same modified recognition strand, reducing fabrication cost and complexity (Figure S1C). The gain and affinity of this modular switch compare closely to those of our non-modular electrochemical sensor (Fig. 2b). As is its specificity: the modular sensor is, as shown, insensitive to the addition of 3 μM of human-mixed antibodies (dashed line). The titrations shown in this figure represent the average of measurements conducted with three independently fabricated sensors, with error bars reflecting standard deviation.

Unlike previously reported, single-step antibody measurement methods8,9,15,32–34 the structure switching mechanism underlying this new antibody sensor architecture is selective enough to employ directly in whole blood (Figure 4). Indeed, the gain and detection limit observed when the sensor is deployed directly in whole blood (Figure 4, top) are very close to those observed when the sensor is employed in simple buffer solutions. This close similarity suggests that the electrochemical switch should remain relatively insensitive to sample-to-sample variations other than those associated with a change in the specific antibody concentration (e.g. change in pH, ionic strength, etc).

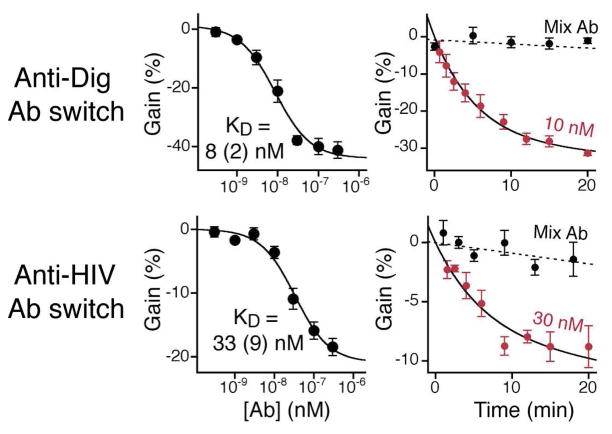

Figure 4.

Antibody-switches support the rapid detection of various specific antibodies directly in whole blood with response time constants of less than 5 minutes. Top: The anti- Dig antibody sensor performs similarly well when challenge directly in whole blood and produces a rapid decrease in the current signal with 10 nM of the relevant antibody targets (response time of less than 5 min), but not when the blood is doped with a mixture of 30 nM of an anti-HIV antibody (see below) and a 100-fold higher concentration of random, pooled human IgGs (dotted line). We also tested a switch containing a 14-residue polypeptides epitope taken from the HIV-1 protein gp41 that is specifically recognized by the clinically relevant anti-HIV-antibody AF5. The switch also performed robustly in whole blood with gain (20%), detection limit (10 nM) and response time that compare to those of the anti-Dig-antibody switch. The titrations and kinetics shown in this figure represent the average of measurements conducted with three independently fabricated sensors, with error bars reflecting the standard deviation.

The modular switch improves the ease with which we can attach and employ more complex and clinically relevant antigens, including polypeptide epitopes. To demonstrate this we fabricated and tested a switch presenting an 14- residue epitope from the HIV-1 protein gp41 that binds the clinically relevant anti-HIV-antibody AF5. Again the switch performed robustly in whole blood (gain ~20%, detection limit ~10 nM) with a response time that is similar to that of the anti-Dig-Ab switch (Figure 4, bottom). The origins of the smaller gain display by the anti-HIV-antibody sensor is unclear, but it could arise due to the larger recognition element (~ 18 amino acids) employed in this sensor as this will likely destabilize the stem-loop via steric repulsion, which in turn will raise Ks and reduce the population-shift seen upon antibody addition. Alternatively, the average distance between the epitope binding sites may differ from antibody to antibody, which could effect the extent to which the open, target-bound state is “off”.

Here we have described a new class of bio-electrochemical switches for the detection of specific antibodies. These respond rapidly (< 5 min) and sensitively to their targets at low nanomolar concentrations and perform well even when challenged directly in undiluted whole blood. Moreover, this new class of electrochemical switches is versatile; here we have shown that they support the use of both small-molecule haptens and polypeptide epitopes for antibody detection, but, we believe, they can likely be engineered to support the detection of even non-antibody targets as long as the target presents two or more recognition sites spaced enough apart to induce the required stem opening.

As the basis for sensors the switches described may provide significant advantages relative to existing antibody detection technologies. Despite the recent development of innovative homogeneous immunoassays37, for example, current methods for the quantitative detection of antibodies still mostly rely on ELISAs and Western Blots, multi-step, wash- and reagent-intensive processes that necessitate specialized technicians and require several hours. Immunochemical dipsticks, in contrast, are far more convenient and are well suited for point-of-care applications, but they are qualitative38. Switch-based sensors, in contrast, are quantitative and laboratory-based assays but can likely also be adapted to convenient point-of-care formats39. Finally, due to the high selectivity of their structure-switching signaling mechanism, the antibody-activated switches are relatively insensitive to the non-specific absorption of interferents even when challenged with samples as complex as undiluted whole blood. Given the advantages the switches presented here offer over existing technologies they appear to be well positioned for adaptation as, for example, point-of-care diagnostic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Kevin Cash, Dr. Ron Cook and Mr. Brett Cook (the latter two of Biosearch Technologies), Dr Frédéric Sauvé, Dr. Alexandre Benoît, and members of the lab for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant R01EB007689 (KWP), by the Fond Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies (AVB), by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Grand Challenges Explorations Grant Number: OPP1061203 (FR), by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR) through the project FIRB “Futuro in Ricerca” (FR) and partially by the IMI Program of the National Science Foundation under Award No. DMR 0843934 (AVB).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Supporting methods, figures and references. This material is available free of charge at HTTP://PUBS.ACS.ORG.

References

- 1.Urdea M, Penny LA, Olmsted SS, Giovanni MY, Kaspar P, Shepherd A, Wilson P, Dahl CA, Buchsbaum S, Moeller G, Hay Burgess DC. Nature. 2006;444(Suppl 1):73–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malkin RA. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:567–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yager P, Domingo GJ, Gerdes J. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;10:107–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mrksich MS, GB, Whitesides GM. Langmuir. 1995;11:4383–4385. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glidle A, Yasukawa T, Hadyoon CS, Anicet N, Matsue T, Nomura M, Cooper JM. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2559–70. doi: 10.1021/ac0261653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walt DR. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2876–80. doi: 10.1021/nn901295n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heyduk T, Ma Y, Tang H, Ebright RH. Methods Enzymol. 1996;274:492–503. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cash KJ, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6955–7. doi: 10.1021/ja9011595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerasimov JY, Lai RY. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:8688–90. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12783g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White RJ, Kallewaard HM, Hsieh W, Patterson AS, Kasehagen JB, Cash KJ, Uzawa T, Soh HT, Plaxco KW. Anal Chem. 2012;84:1098–103. doi: 10.1021/ac202757c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:303–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson DE, Conrad DW, de Lorimier RM, Trammell SA, Hellinga HW. Science. 2001;293:1641–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1062461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stojanovic MN, de Prada P, Landry DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4928–31. doi: 10.1021/ja0038171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan C, Plaxco KW, Heeger AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9134–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golynskiy MV, Rurup WF, Merkx M. Chembiochem. 2010;11:2264–7. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallee-Belisle A, Bonham AJ, Reich NO, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13836–9. doi: 10.1021/ja204775k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho EJ, Lee JW, Ellington AD. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2009;2:241–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Tang Z, Yang CJ, Kim Y, Fang X, Li W, Wu Y, Medley CD, Cao Z, Li J, Colon P, Lin H, Tan W. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:856–70. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Cao Z, Lu Y. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1948–98. doi: 10.1021/cr030183i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vallée-Bélisle A, Plaxco KW. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stratton MM, Loh SN. Protein Sci. 2011;20:19–29. doi: 10.1002/pro.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golynskiy MV, Koay MS, Vinkenborg JL, Merkx M. Chembiochem. 2011;12:353–61. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubin AA, Plaxco KW. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:496–505. doi: 10.1021/ar900165x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sosnick TR, Benjamin DC, Novotny J, Seeger PA, Trewhella J. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1779–86. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian L, Heyduk T. Biochemistry. 2009;48:264–75. doi: 10.1021/bi801630b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haugland RP. The Handbook. A guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies. 10. San Diego: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallée-Bélisle A, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eshhar Z, Ofarim M, Waks T. J Immunol. 1980;124:775–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marras SA, Kramer FR, Tyagi S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J. Chem Rev. 2008;108:814–25. doi: 10.1021/cr068123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins HM, Vallee-Belisle A, Ricci F, Makarov DE, Plaxco KW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2120–6. doi: 10.1021/ja208436p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGiven JA, Tucker JD, Perrett LL, Stack JA, Brew SD, MacMillan AP. J Immunol Methods. 2003;278:171–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian L, Heyduk T. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5218–25. doi: 10.1021/ac900845a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolduc OR, Pelletier JN, Masson JF. Anal Chem. 2011;82:3699–706. doi: 10.1021/ac100035s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper HM, Paterson Y. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 2(Unit 2):4. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0204s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manz RA, Arce S, Cassese G, Hauser AE, Hiepe F, Radbruch A. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:517–21. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith DS, Eremin SA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:1499–507. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1897-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong R. Lateral Flow Immunoassay. Humana Press; New-York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowe AA, Chuh KN, Lubin AA, Miller EA, Cook B, Hollis D, Plaxco KW. Anal Chem. 2011;83:9462–6. doi: 10.1021/ac202171x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.