Abstract

Here we demonstrate multiple, complementary approaches by which to tune, extend or narrow the dynamic range of aptamer-based sensors. Specifically, we have employed both distal site mutations and allosteric control to tune the affinity and dynamic range of a fluorescent aptamer beacon. We show that allosteric control, achieved by using a set of easily designed oligonucleotide inhibitors that competes against the folding of the aptamer, allows to rationally and finely tune the affinity of our model aptamer across three orders of magnitude of target concentration with greater precision than that achieved using mutational approaches. Using these methods we generate sets of aptamers varying significantly in target affinity, which we then combined to recreate several of the mechanisms employed by nature to both narrow and broaden the dynamic range of biological receptors. Such ability to finely control the affinity and dynamic range of aptamers may find many applications in synthetic biology, drug delivery and targeted therapies, fields in which aptamers are of rapidly growing importance.

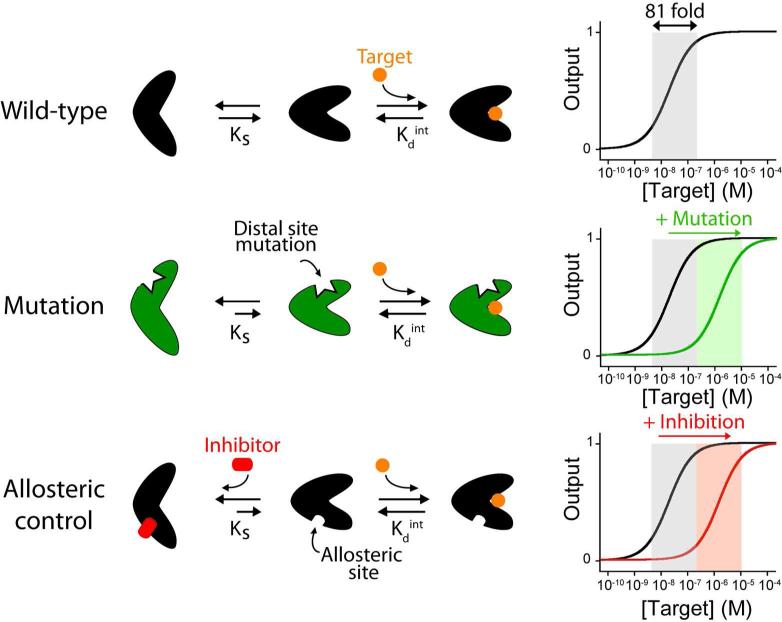

The impressive affinity and specificity with which biomolecules recognize their targets has led to the widespread use of proteins and nucleic acids in molecular diagnostics1. Despite the well-demonstrated utility of biological recognition, however, its use in artificial technologies is not without a potentially significant limitation: the single-site binding characteristic of most biological receptors produces a hyperbolic dose-response curve with a fixed dynamic range (defined here as the interval between 10% and 90% of total activity) spanning almost two orders (81-fold) of magnitude (Figure 1, top)2. This fixed dynamic range limits the usefulness of such receptors in applications requiring the measurement of target concentration over many orders of magnitude. Other applications, such as molecular logic gates, biomolecular systems programmed to integrate multiple inputs (i.e., multiple disease biomarkers) into a single output3, could likewise benefit from strategies that provide steeper, more “digital” input-output response curves4.

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of some of the strategies used by nature to tune the affinity of her receptors. (Top) For many receptors target binding shifts a pre-existing equilibrium between a binding competent state and a non-binding state10. The affinity of the receptor for its target is a function of both the intrinsic affinity of the binding-competent state (Kdint) and the switching equilibrium constant, Ks. (Middle) Mutations at the distal site of the receptor can stabilize the non-binding state thus shifting the dynamic range towards higher target concentrations. (Bottom) The binding of an allosteric inhibitor can also be used to stabilize the non-binding state, reducing Ks and thus raising the overall dissociation constant.

As it is true in artificial technologies, the fixed dynamic range of single-site binding also represents a potentially significant limitation in nature and thus, in response, evolution has invented a number of mechanisms by which to tune, extend, or narrow the dynamic range of biomolecular receptors. Binding-site mutations, for examples, are often used to produce receptors of varying affinity, optimizing the dynamic range of a sensor over the course of many generations5. Alternatively, nature often tunes the dynamic range of its receptors in real time using allosteric effectors6, which bind to distal sites on a receptor to change its target affinity7. Using still other mechanisms nature modulates the shape of the input-output curves of its receptors. For example, nature often couples sets of related receptors spanning a range of affinities to achieve broader dynamic ranges than those observed for single site binding8. Nature also similarly combines signaling-active receptor with a non-signaling, high affinity receptor (a “depletant”) to create ultrasensitive dose-response curves characterized by very narrow dynamic ranges9.

In previous work we have shown that the above mechanisms can be employed to extend, narrow or otherwise tune the dynamic range of molecular beacons, a commonly employed fluorescent DNA sensor comprising of a double-stranded stem linked by a single-stranded loop1,11. For example, by “mixing and matching” sets of molecular beacons varying in target affinity we have produced sensors with input-output (target concentration/signal) response curves spanning a range of widths and shapes2. However, the simple, easily modeled structure of molecular beacons renders the tuning of their affinity an almost trivial exercise. In contrast, the process of altering the affinity of more complex biomolecules (often of unknown structure) is more challenging. In response, we demonstrate here the use of distal-site mutations and allosteric control (Figure 1) to extend, narrow or otherwise tune the dynamic range of an important, broader class of biosensors: those based on the use of nucleic acid aptamers.

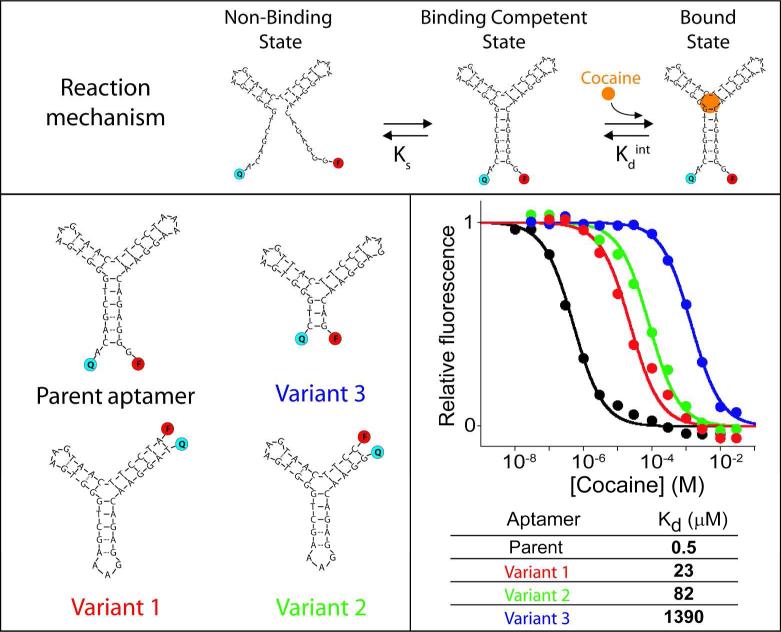

As a test bed for our studies we have employed the classic cocaine-binding DNA aptamer, which is thought to fold into a three-way junction upon binding to its target analyte (Figure 2, Top)13. Because this binding-induced folding brings the aptamer's ends into proximity, the attachment of a fluorophore (FAM) and a quencher (BHQ) to these termini is sufficient to generate a fluorescent sensor13a (Figure 2, Top). As expected, the output of this sensor exhibits the classic hyperbolic binding curve (the so-called “Langmuir isotherm”) characteristic of single site binding, for which the useful dynamic range (again, defined here as the interval between 10% and 90% of total activity) spans almost two orders of magnitude (Figure 2, black curve).

Figure 2.

Tuning affinity of an aptamer by using distal site mutations to alter its conformational switching equilibrium constant. We designed variants of the cocaine-binding aptamer that likely display lower switching equilibrium constant (and thus weaker overall affinity) by changing the parent oligonucleotide sequence to destabilize the aptamer's target-binding conformation. By doing so we obtained a series of aptamers (only four shown here; see other variants in Figure S1), with affinity constants spanning more than 3 orders of magnitude. Variant 1: a circular permutant; variant 2: a truncation of that circular permutant; variant 3: a truncation of the parent sequence. As expected for single-site binding, the useful dynamic ranges of all these variants span the characteristic 81-fold range of target concentration.

To tune the dynamic range of the cocaine sensor we first generated a set of sequence-altered aptamers (variants, Figure 2 and Figure S1). Guided by the predicted secondary structure (and target binding site) of the aptamer13, the variants we designed were intended to affect the affinity of the aptamer by destabilizing its folded, binding-competent, state rather than by directly interfering with the target binding itself10. The alterations we explored included simple nucleotide substitutions (Figure S1), shortening the length of the terminal stem (Figure 2: variant 2 and 3), and circular permutation of the sequence (Figure 2: variant 1). Using this approach we obtained aptamers with dissociation constants ranging from 23 to 1390 μM (versus 0.5 μM for the parent sequence). The mutational approach thus allowed us to produce receptors with affinities spanning ~3 orders of magnitude. In characterizing these variants, however, we found that, in the absence of detailed structural information, it is difficult to predict how any given alteration would change the affinity of the aptamer, rendering this approach to affinity tuning semi-rational at best (see, e.g., Figure S1).

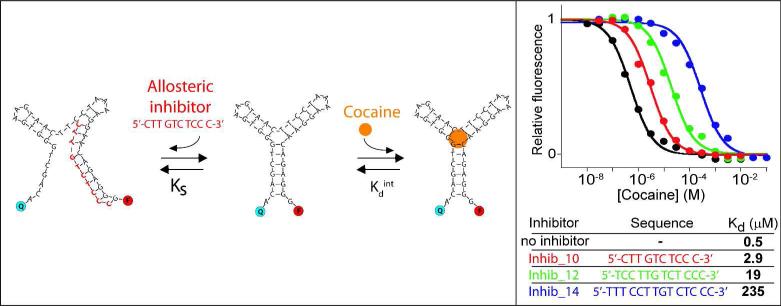

As the above examples illustrate, in the absence of detailed, three-dimensional structural knowledge (as opposed to the predicted secondary structure) it is difficult to ensure that a given mutation will significantly alter affinity, rendering mutagenesis approaches to generate aptamers of a given affinity an inefficient, “hit-or-miss” proposition. A second, potentially equally important concern is that in the absence of detailed structural knowledge it is difficult to ensure that the alterations change the affinity by modifying the conformational equilibrium rather than modifying target binding directly14. For this reason the mutational approach may lead to variant aptamers differing in specificity from the parent sequence and, in turn, lead to changes in the specificity profile of the resultant sensor. Given this we explored an alternative strategy to rationally tune the affinity of an aptamer: the use of allosteric inhibitors (Figure 1, bottom). To do this we designed unlabeled DNA oligonucleotides complementary to portions of the aptamer (here, complementary to its 5'-terminal region) that reduce affinity by stabilizing a non-binding conformation. As expected, the extent of inhibition is related to the concentration and length (and thus binding affinity) of the inhibitor (Figure S2), with longer (i.e., more tightly binding) inhibitors and higher inhibitor concentrations producing greater inhibition. Using this approach we can fine tune the dynamic range of our aptamer over ca. 3 orders of magnitude (Figures 3 and Figure S3). Thus, in comparison to the “mutation” approach described above, the use of allosteric control provides a more predictable route to altering target affinity. Moreover, because it alters affinity by altering the conformational equilibrium constant of the aptamer, the allosteric approach does not alter the structure of the aptamer's binding site and thus does not alter the aptamer's specificity11a.

Figure 3.

The affinity of the cocaine-binding aptamer can be efficiently and precisely tuned using allosteric inhibition. To do this we designed oligonucleotides complementary to a sequence within the parent aptamer such that hybridization with the inhibitor competes with folding of the aptamer into its binding-competent conformation. By varying the length and/or concentration (and thus hybridization energy) of the inhibitor we can then tune the affinity of the aptamer over many orders of magnitude. As expected for single-site binding the useful dynamic range of the inhibited aptamer still spans the classic 81-fold of target concentration as the presence of the inhibitor only affects the switching equilibrium thermodynamics and not the signalling mechanism. Here the inhibitor concentration was held at 100 nM concentration except for shortest inhibitor (inhib_10) which was set at 300 nM (see also Figure S3).

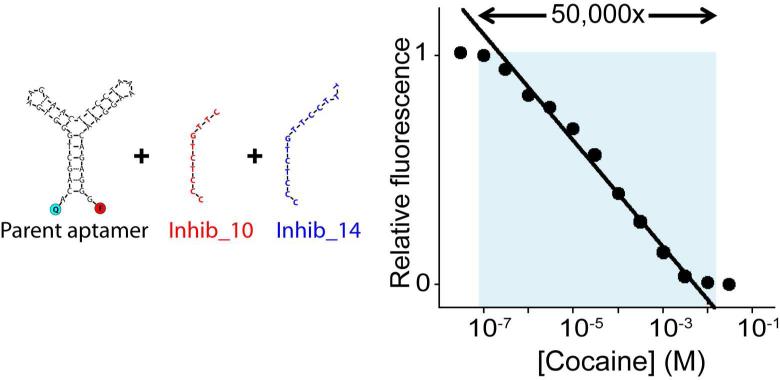

The possibility to tune the affinity of our aptamer over a wide range of concentration provides a means of modulating the shape of the input-output curve. For example we have extended the dynamic range of the cocaine sensor via the addition of a mixture of allosteric inhibitors acting on a single labelled aptamer sequence. More specifically, by using a combination of two inhibitors differing in length (10mer and 14mer) that shift the affinity of the parent aptamer (0.5 μM) to 2.9 μM and 235 μM, respectively, we extended the 81-fold useful dynamic range of the parent aptamer to 50,000-fold (Figure 4). Of note, the precise control achievable via allosteric tuning renders it possible to generate affinities differing by 82.4-fold, which is close to the optimal 100-fold difference that generates the longest possible log-linear range2.

Figure 4.

Extending the dynamic range with allosteric control. We have extended the useful dynamic range of our model cocaine sensor to 50,000-fold using a single aptamer sequence (the parent sequence) and a mixture of two allosteric inhibitors of different length (10mer and 14mer). Here concentration of the aptamer was 125 nM and the two inhibitors (inhib_10 and inhib_14) were used at 44 nM and 56 nM respectively.

We have also extended the dynamic range of the cocaine aptamer sensor via the use of the variants achieved with the mutational approach. For example, by combining (in one test tube) four variants of the fluorescent cocaine sensor with affinities spanning some three orders of magnitude we produced a sensor with a dynamic range of 330,000-fold across which the sensor exhibits excellent log-linearity (R2 = 0.987; Figure S4). We note that the relative concentration of each aptamer in this “sensor” (Figure S4) must be tuned depending on its gain (Figure S5) to achieve good log-linearity. That is, simple equimolar combinations of receptors leads to deviations from ideal, log-linear behaviour, an effect that we can correct by optimizing the relative amount of each in the solution (optimal ratios obtained via simulation)2.

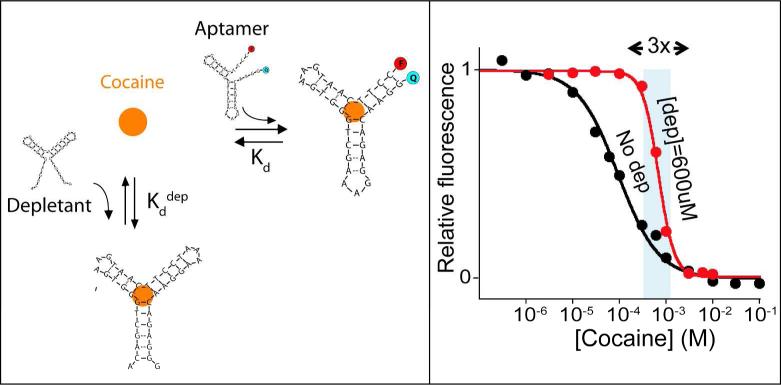

The availability of sets of aptamers varying in affinity also provides a means of achieving narrower dynamic ranges via the sequestration mechanism (Figure 5), a strategy employed by nature to achieve ultrasensensitive responses in genetic networks9,12,15. Specifically we have employed a lower-affinity signalling aptamer (variant 2, Kd = 82 μM) together with a higher-affinity non-signalling receptor (the unlabeled parent aptamer, Kd = 4 μM) that acts as a depletant, holding the concentration of free target low until the depletant is saturated12. When the total cocaine concentration surpasses the concentration of depletant (here 600 μM) any further addition drastically raises the relative concentration of free cocaine thus, in turn, saturating the signalling aptamer beacon and generating an ultrasensitive output. By doing so we can narrow the useful 81-fold dynamic range of a traditional aptamer to just 3-fold (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Narrowing the dynamic range of an aptamer using the sequestration mechanism. (Left) We have also narrowed the dynamic range of our model sensor using the sequestration mechanism. This mechanism employs a high affinity non-signalling “depletant” aptamer (here the unlabelled high-affinity parent aptamer) that acts as a “sink,” holding the concentration of free target low until it is saturated. Upon saturation the free target concentration rises very rapidly, activating a signalling-competent, but lower affinity aptamer (here variant 2). (Right) Using this strategy we have narrowed the 81-fold useful dynamic range of the cocaine sensor to just ~3-fold.

Here we have demonstrated multiple, complementary approaches by which we can tune, extend or narrow the dynamic range of a model aptamer-based sensor. Specifically, using distal site mutations and allosteric control we have generated sets of aptamers varying significantly in target affinity. Using combinations of these we then recreated several of the mechanisms employed by nature to narrow or broaden the dynamic range of biochemical receptors, showing that the strategies previously employed to rationally modify the dynamic range of molecular beacons2 can be generalized to more complex –and thus perhaps more useful- receptors.

As previously demonstrated, distal-site mutations can be used to alter the affinity of biomolecular receptors16. However, these strategies present cost and time limitations similar to those faced by nature's use of mutations to optimize function17. Indeed, as we have found, neither point mutation (Figure S1), circular permutation, nor stem truncation proved an efficient means to generate large changes in affinity for the cocaine aptamer. The allosteric approach to modulating affinity, in contrast, provides a more rational, efficient and likely reversible approach by which we can tune the affinity of an oligonucleotide-based receptor. Specifically, by varying the length and/or concentration of a set of easily designed oligonucleotide inhibitors we were able to finely tune the affinity of our model aptamer across three orders of magnitude of target concentration with great precision. A potential limitation of this approach, however, is that such strategy generates sensors with slower time response due to the slow release rate of the inhibitor from the aptamer. With the inhibitor 12mer, for example, the sensor's equilibration time constant is raised up to ~50 s while the time response of the parent aptamer for cocaine is as low as few tens of milliseconds (Figure S6).

Although it has been previously demonstrated that the catalytic activity of DNAzymes, ribozymes and enzymes can be allosterically controlled18,19, relatively few examples have been reported in which allostery has been used to rationally control ligand binding11,19,20. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge no previous examples have been reported where a short DNA oligonucleotide has been used to rationally modulate the switching thermodynamics of an aptamer in order to finely tune its affinity and dynamic range.

Besides the obvious applications in biosensor design explored in this work, the possibility to finely control the affinity of aptamers would appear to open the door to applications across synthetic biology, drug delivery and targeted cancer therapy, fields in which aptamers are of rapidly growing importance. Aptamers, for example, have been developed against a variety of cancer targets, including extracellular ligands and cell surface proteins21, and the possibility to finely tune and control their target affinity could be of utility in the fine control of therapies based on their use. Aptamers have also been employed as delivery agents of siRNAs, small-molecule chemotherapeutics, and nanoparticle-based therapies22, applications in which the ability to tune or otherwise edit their dynamic range could be used to better control their delivery. More generally, approaches similar to those demonstrated here could be employed to achieve the rational control of gene expression. This would result in protein expression and activity and gene regulation that are not just allosterically controlled (a feature that has been previously demonstrated23) but that can be rationally and finely regulated by controlling the concentration of the allosteric species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the MIUR (FIRB “Futuro in Ricerca”) (FR), by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Grand Challenges Explorations (OPP1061203) (FR), by the International Research Staff Exchange Scheme (IRSES) grant under the Marie Curie Actions program (FR), by the NIH through grant R01EB007689 (KWP) and by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec Nature et Technologies (FRQNT) (AVB). FR is supported by a Marie Curie Outgoing Fellowship (IOF) (Proposal No. 298491under FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IOF).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Supporting methods, figures. This material is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.a Cheng MM, Cuda G, Bunimovich YL, Gaspari M, Heath JR, Hill HD, Ferrari M. Curr. Op. Chem. Biol. 2006;10(1):11. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006;21:1887. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallée-Bélisle A, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(6):2876. doi: 10.1021/ja209850j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Halámek J, Zhou J, Halámková L, Bocharova V, Privman V, Wang J, Katz E. Anal. Chem. 2011;83(22):8383. doi: 10.1021/ac202139m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Katz E, Privman V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39(5):1835. doi: 10.1039/b806038j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafael PS, Vallée-Bélisle A, Fabregas E, Plaxco K, Palleschi G, Ricci F. Anal. Chem. 2012;84(2):1076. doi: 10.1021/ac202701c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Benner SA. Chemical Reviews. 1989;89(4):789. [Google Scholar]; b Huang CF, Ferrell JE., Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93(19):10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tsai C, Del Sol A, Nussinov R. Mol. BioSyst. 2009;5(3):207. doi: 10.1039/b819720b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Q, Karplus M. Protein Science. 2008;17(8):1295. doi: 10.1110/ps.03259908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a del Sol A, Tsai C, Ma B, Nussinov R. Structure. 2009;17(8):1042. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kar G, Keskin O, Gursoy A, Nussinov R. Curr. Op. Pharm. 2010;10(6):715. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom JD, Arnold FH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:9995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901522106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchler NE, Cross FR. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009:5. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallée-Bélisle A, Ricci F, Plaxco KW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:13802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Ricci F, Vallée-Bélisle A, Plaxco KW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(7):15177. doi: 10.1021/ja304672h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kang D, Vallee-Belisle A, Porchetta A, Plaxco KW, Ricci F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51(27):6717. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricci F, Vallée-Bélisle A, Plaxco KW. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2011;7(10):e1002171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a Stojanovic MN, de Prada P, Landry DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123(21):4928. doi: 10.1021/ja0038171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cekan P, Jonsson EÖ, Sigurdsson ST. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(12):3990. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Elowitz MB, Leibier S. Nature. 2000;403:335. doi: 10.1038/35002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kim J, White KS, Winfree E. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallée-Bélisle A, Plaxco KW. Curr. Opinion Struct. Biol. 2010;20(4):518. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a Mizoue LS, Chazin WJ. Curr. Opinion Struct. Biol. 2002;12(4):459. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Velazquez-Campoy A, Todd MJ, Vega S, Freire E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98(11):6062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Jäckel C, Kast P, Hilvert D. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Toscano MD, Woycechowsky KJ, Hilvert D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46(18):3212. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Choi B, Zocchi G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8541. doi: 10.1021/ja060903d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Choi B, Zocchi G, Canale S, Wu Y, Chan S, Jeanne Perry L. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:038103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.038103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Famulok M, Hartig JS, Mayer G. Chem. Rev. 2007;107(9):3715. doi: 10.1021/cr0306743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Liu J, Lu Y. Adv. Mat. 2006;18(13):1667. [Google Scholar]; e Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Famulok M. Blood Cell Mol. Dis. 2007;38(1):19. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Pelossof G, Tel-Vered R, Elbaz J, Willner I. Anal. Chem. 2010;82(11):4396. doi: 10.1021/ac100095u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Robertson MP, Ellington AD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(8):1751. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Tang J, Breaker RR. Chem. Biol. 1997;4(6):453. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Teller C, Shimron S, Willner I. Anal. Chem. 2009;81(21):9114. doi: 10.1021/ac901773b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2003;4(10):1024. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinkenborg JL, Karnowski N, Famulok M. Nature Chem. Biol. 2011;7(8):519. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida W, Sode K, Ikebukuro K. Anal. Chem. 2006;78(10):3296. doi: 10.1021/ac060254o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a Barbas AS, Mi J, Clary BM, White RR. Future Onc. 2010;6(7):1117. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ireson CR, Kelland LR. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5(12):2957. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a Hicke BJ, Stephens AW, Gould T, Chang Y, Lynott CK, Heil J, et al. J. Nucl. Med. 2006;47(4):668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Levy-Nissenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:442. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a Lefstin JA, Yamamoto KR. Nature. 1998;392(6679):885. doi: 10.1038/31860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Maung NW, Smolke CD. Science. 2008;322(5900):456. doi: 10.1126/science.1160311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vuyisich M, Beal PA. Chem. Biol. 2002;9(8):907. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Werstuck G, Green MR. Science. 1998;282(5387):296. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99(25):15908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.