This report discusses the association of ovarian lymphoma and hydroureteronephrosis managed by laparoscopic surgery and endoscopy.

Keywords: Ovarian lymphoma, Ureterolysis, Laparoscopic surgery

Abstract

Introduction:

Ovarian lymphoma is a rare entity, and hydronephrosis from lymphoma is even rarer. Most reports describe a laparoscopic approach to the disease, but we report a case of hydroureteronephrosis associated with ovarian lymphoma managed completely by mini-invasive techniques.

Case Report:

A 51-year-old woman was referred to us for back pain and renal colic and computed tomography scan findings of right hydroureteronephrosis and a mass in the right mesorectum and uterosacral ligament.

After magnetic resonance imaging was performed, the patient underwent laparoscopic adnexectomy and ureterolysis after ureteroscopy and stenting. Histology results showed diffuse B-cell lymphoma of the ovary occluding the ureter without infiltration. The patient has undergone 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

Discussion:

This is the first report to describe ovarian lymphoma and hydroureteronephrosis managed completely by laparoscopic surgery and endoscopy. Frequency in clinical practice, differential diagnosis, and endoscopic approach are discussed. The advantages of a multidisciplinary endoscopic team are underlined.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian lymphoma is a rare disease presenting in approximately 0.5% of all patients undergoing surgery for ovarian mass and accounting for approximately 1.5% of all ovarian tumors.1–3 Most of the literature relies on case reports of large masses that are managed like ovarian cancer.4–6 Furthermore, lymphomas involving the ureter precociously are even rarer.7,8

We report a case of lymphoma involving the ovary and the ureter, presenting with hydroureteronephrosis, which was managed exclusively by combined endoscopic surgery and chemotherapy.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old patient was referred to us for back pain and hydroureteronephrosis. She was still menstruating regularly and had already been treated for renal colic and complained about weight loss, but was completely free of other symptoms. A previous computed tomography (CT) scan had visualized hydroureteronephrosis with a 4-mm possible stone within the right ureter and solid tissue at the level of the mesorectum and uterosacral ligament on the same side.

Abdominal examination did not show any mass or swelling. However, pelvic examination revealed an approximately 2-cm nodule in the rectovaginal septum on the right side that was not painful on palpation, as well as 2 smaller nodules in the vesicovaginal septum located below the bladder-vescical trigonum. Transvaginal ultrasound showed the nodules and thickened endometrium, suggesting the secretory phase and that the right ovary was only slightly enlarged. A magnetic resonance imaging scan was requested, which showed the nodules and more lesions located in the mesorectum. Small lymph nodes (7–8 mm) were visible in the pelvis. The right ureter was thickened in the pelvic part and dilated in the upper part. Magnetic resonance imaging findings also showed an endoureteral mass, suggesting either endometriosis or a transitional epithelial tumor, but not a stone. On visualization, the ovaries were considered normal.

Chest radiography revealed no abnormalities. Blood counts were normal, with the exception of iron deficiency, and were negative for the CA-125 antigen.

We decided to access the pelvis laparoscopically to perform ureterolysis and biopsies in the rectovaginal septum, while ureteroscopy and eventual stenting could be performed during the same surgery.

At surgery, ureteroscopy was performed and no lesion was found in the ureteral lumen, so stenting was done. Meanwhile, laparoscopy was performed and the right ovary was found to be strictly adherent to the ovarian fossa infiltrated from the infundibulopelvic ligament by whitish fibrous tissue that also infiltrated the broad ligament peritoneum and the retroperitoneum placed below, between the gonadal vessels to the uterine artery and the anterior parametrium. Then laparoscopic right adnexectomy and ureterolysis were completed, freeing the ureter from the surrounding tissue up to the point where the ureter was healthy and below the uterine artery. The infundibulopelvic ligament was severed well above the pelvic brim to cut into healthy tissue. The peritoneum of the broad ligament, that of the ovarian fossa, and the solid retroperitoneal tissue surrounding the ureter were removed together with the ovary. The ureter was actually compressed by the fibrous tissue but not infiltrated, and no other procedure was accomplished. The abdomen, the uterus, and the contralateral ovary did not show any lesion, so they were not removed. No endometriosis was visible in the pelvis, so we ended the procedure with the belief that an infiltrating tumor was the cause of stenosis and then waited for a positive diagnosis.

The patient's postoperative course was normal, and she was discharged with the stent on the fourth postoperative day because of hematuria.

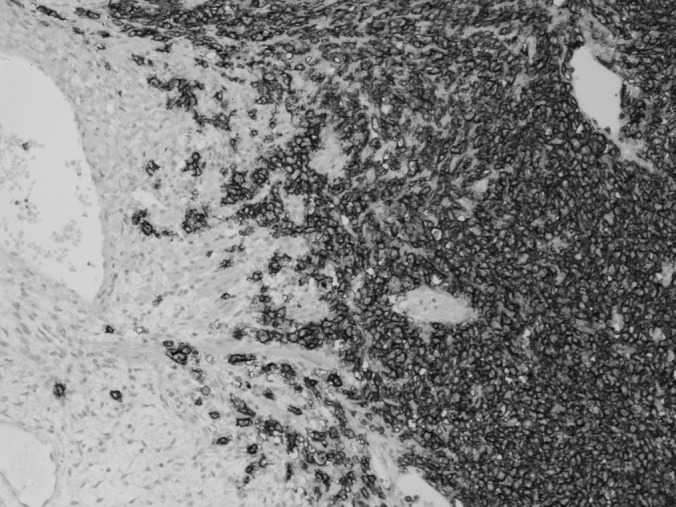

Histology demonstrated B-cell lymphoma (Figure 1) with germinal-like phenotype infiltrating the ovary with diffuse growth. B-cell lymphoma originated from the peripheral fraction. Cytology results of the peritoneal washing were negative. Immunohistochemistry findings demonstrated reactivity to CD20 and BCL-6 and weak reactivity to CD10. No reactivity was shown to CD3, CD30, IRF4, IRTA1-, and BCL-2. The proliferative fraction was evaluated to be 60% to 70%.

Figure 1.

Histology of the B-cell lymphoma infiltrating the ovary.

Staging was performed by computed tomography scan of the thorax and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. No lesions could be visualized using either diagnostic tool.

According to the American Joint Commission on Cancer classification system,9 the disease was confirmed to be stage IIE.

The patient has undergone 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION

Lymphoma of the ovary is a rare condition, and most of the reported series are case reports.4–8 Furthermore, the majority of patients with ovarian lymphoma are in the advanced stages of the disease2,10 or have large ovarian masses.1,2 Thus, most of the patients with large masses also undergo laparoscopic staging for ovarian cancer,1,4,5,6 but lymphoma requires medical treatment more than surgical treatment. In addition, hydronephrosis as a first symptom of lymphoma is rarely reported,7,8 but this is the first time we have seen the association between hydronephrosis and ovarian lymphoma. The question about the origin of primary ovarian lymphoma is debated,2 and in this case, the exact origin of the disease is unknown. However, the involvement of the ovary as a secondary site is believed to be a late symptom of the disease.2,10

We want to underline that complete endoscopic access (both urological and gynecological) can limit the aggressiveness of surgery primarily in patients for whom the diagnostic challenge is great. The choice for laparoscopy instead of a direct biopsy of the palpable nodules was made because of the difficulty in performing such biopsies at the level of the vesicovaginal fascia at the trigonal level and in the rectovaginal septum from below. Ureteral reimplantation was planned in case the disease directly infiltrated the ureter. No consensus was obtained for complete staging in the case of ovarian malignancy.

Laparoscopic ureterolysis is a difficult procedure that is mostly indicated in retroperitoneal fibrosis.11–13 Keehn et al12 reported 3 cases of ureterolysis in lymphoma. However, minimally invasive surgery is now becoming the standard approach for ureterolysis.11–13 In gynecology, the most frequent disease associated with ureteral stenosis is endometriosis, so ureterolysis is frequently performed.14

In our experience, freeing the ureter from endometriosis does not routinely require stenting. We have almost never recommended ureteral catheterization in these patients, but in this case, placing a stent in the ureter was a precautionary procedure because we were uncertain about the presence of a stone or of an endoureteric lesion, and because in tumors the catheter can protect the ureter in cases that involve radiotherapy. Some authors suggest that routine prophylactic stenting may be beneficial in gynecological procedures,15,16 but most of the literature17,18 and a large prospective study19 do not show the benefits of the procedure.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are most frequently seen in the genital tract, accounting for approximately 90% of the cases.1,2 In our case, histology and histochemistry demonstrated B-cell lymphoma. A frozen section taken for biopsy was not requested because the surgery suggested sarcoma or lymphoma as a possible diagnosis. A frozen biopsy section is limited in diagnosing diseases, and complete staging and debulking is requested only for sarcoma.

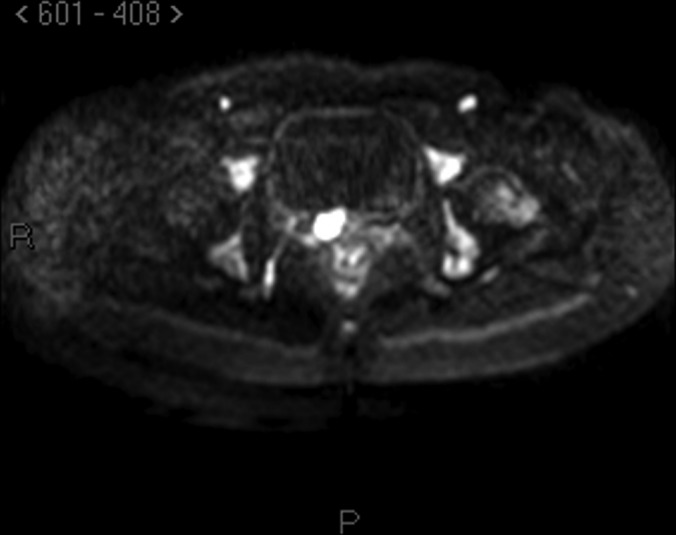

There are also problems in the staging procedure. Now the standard use of PET scan in lymphoma is suggested20 for staging and for follow-up of patients, even if not all authors agree on this.21 Reported sensitivity for lymphoma is approximately 80% to 90% also according to the subtype of lymphoma and to its metabolic activity. In this case, however, PET scan was negative in the pelvis, and, according to our pelvic examination, magnetic resonance with diffusion-weighted imaging, which enhances the sensitivity of the technique, was much more accurate in describing the lesions (Figures 2–4).

Figure 2.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: axial scan showing hydronephrosis.

Figure 3.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: transversal scan of the lesion in the vesico-vaginal septom.

Figure 4.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: diffusion weighted scan showing the same lesion of Figure 3.

In conclusion, a multidisciplinary endoscopic and laparoscopic team can manage cases in which the diagnosis is difficult, limiting the aggressiveness of surgery, but leaving all chances for therapeutic choice. Ovarian lymphoma is a rare disease, and its presentation with hydroureteronephrosis is even rarer. In this case, the mini-invasive approach has allowed precocious return to normal activity for the patient as well as commencement of chemotherapy.

Contributor Information

Eugenio Volpi, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ospedale S. Andrea, LA Spezia, Italy..

Luca Bernardini, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ospedale S. Andrea, LA Spezia, Italy..

Moira Angeloni, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ospedale S. Andrea, LA Spezia, Italy..

Paolo Gogna, Department of Urology, Ospedale S. Bartolomeo, Sarzana, LA Spezia, Italy..

Donatella Intersimone, Department of Pathology, Ospedale S. Andrea, LA Spezia, Italy..

Franco Fedeli, Department of Pathology, Ospedale S. Andrea, LA Spezia, Italy..

References:

- 1. Signorelli M, Maneo A, Cammarota S, et al. Conservative management in primary genital lymphomas: the role of chemottherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:416–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monterroso V, Jaffe ES, Merino MJ, Medeiros LJ. Malignant lymphomas involving the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 39 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:154–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dimopoulos MA, Daliani D, Pugh W, Gershenson D, Cabanillas F, Sarris AH. Primary ovarian non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: outcome after treatment with combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jung IS, Kim SY, Kim KS, et al. A case of primary ovarian lymphoma presenting as a rectal submucosal tumor. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28:111–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bambury I, Wharfe G, Fletcher H, Williams E, Jaggon J. Ovarian lymphoma. J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;31:653–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ambulkar J, Nair R. Primary ovarian lymphoma: report of cases and review of literature. Leuk Lymph. 2003;44:825–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haitani T, Shimizu Y, Inoue T, et al. A case of ureteral malignant lymphoma with concentric thickening of the ureteral wall. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2012;58:209–213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fujisawa H, Takagane H, Shimosegawa K, Sakuma T. Primary malignant lymphoma of the ureter: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004;50:721–724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed New York, NY: Springer; 2010: pp 607–611 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magri K, Riethmuller D, Maillet R. Pelvic Burkitt lymphoma mimicking an ovarian tumor. J Obstet Gynecol Biol Reprod. 2006;35:280–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stifelman MD, Shah O, Mufarrij P, Lipkin M. Minimally invasive management of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Urology. 2008;71:201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keehn AY, Mufarrij PW, Stiefelman MD. Robotic ureterolysis for relief of ureteral obstruction from retroperitoneal fibrosis. Urology. 2011;77:1370–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seixas-Mikelus SA, Marshall SJ, Stephens D, Blumenfeld A, Arnone ED, Guru KA. Robot-assisted laparoscopoic ureterolysis: case report and literature review on the minimally invasive surgical approach. JSLS. 2010;4:313–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Camanni M, Delpiano EM, Bonino L, Deltetto F. Laparoscopic conservative management of ureteral endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abu-Rustum N, Sonoda Y, Black D, et al. Cystoscopic temporary uretera catheterization during radical vaginal and abdominal trachelectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:729–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aungst MJ, Sears CLG, Fischer JR. Ureteral stents and retrograde studies: a primer for gynecologist. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuno K, Menzin A, Kauder HH, et al. Prophylactic ureteral catheterization in gynecologic surgery. Urology. 1998;52:1004–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schimpf MO, Gottenger EE, Wagner JR. Universal ureteral stent placement at hysterectomy to identify ureteral injury: a decision analysis. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;114:1151–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka Y, Asada H, Kuji N, Yoshimura Y. Ureteral catheter placement during laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2008;34:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imataki O, Tamai Y, Yokoe K, Furukawa T, Kawakami K. The utility of FDG-PET for managing patients with malignant lymphoma: analysis of data from a single cancer center. Intern Med. 2009;48:1509–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baba S, Abe K, Isoda T, Maruoka Y, Sasaki M, Honda H. Impact of FDG-PET/CT in the management of lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25:701–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]