Abstract

Background

TMPRSS2:ERG is a hormonally regulated gene fusion present in about half of prostate tumors. We investigated whether obesity, which deregulates several hormonal pathways, interacts with TMPRSS2:ERG to impact prostate cancer outcomes.

Methods

The study included 1243 participants in the prospective Physicians’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1982 and 2005. ERG overexpression (a TMPRSS2:ERG marker) was assessed by immunohistochemistry of tumor tissue from radical prostatectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate. Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, measured on average 1.3 years and 5.3 years before diagnosis, respectively, were available from questionnaires. Data on BMI at baseline was also available. We used Cox regression to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 12.8 years, 119 men developed lethal disease (distant metastases or prostate cancer death). Among men with ERG-positive tumors, the multivariable hazard ratio for lethal prostate cancer was 1.48 (95% CI = 0.98 to 2.23) per 5-unit increase in BMI before diagnosis, 2.51 (95% CI = 1.26 to 4.99) per 8-inch increase in waist circumference before diagnosis, and 2.22 (95% CI = 1.35 to 3.63) per 5-unit increase in BMI at baseline. The corresponding hazard ratios among men with ERG-negative tumors were 1.10 (95% CI = 0.76 to1.59; P interaction = .24), 1.14 (95% CI = 0.62 to 2.10; P interaction = .09), and 0.78 (95% CI = 0.52 to 1.19; P interaction = .001).

Conclusions

These results suggest that obesity is linked with poorer prostate cancer prognosis primarily in men with tumors harboring the gene fusion TMPRSS2:ERG.

Prostate cancer patients who are overweight have greater risk of disease recurrence and cancer-specific mortality (1,2). In the United States, 238590 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2013, and two-thirds of the adult male population is overweight or obese (3,4). Thus, understanding the mechanisms linking excess bodyweight with worse prostate cancer outcomes has important public health implications. Obesity deregulates multiple pathways that could influence disease outcomes. For example, circulating levels of insulin, free insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1), adiponectin, and sex hormones are altered in obese vs normal-weight men (5,6).

The common gene fusion TMPRSS2:ERG is present in half of prostate cancers (7,8). TMPRSS2 is regulated by androgens and possibly estrogens (9), and the oncogene ERG is a member of the ETS transcription factor family. Its discovery in 2005 was notable both because it was the first identification of a common gene fusion in a common solid tumor and because it represents a model of hormonal regulation of an oncogene. Based on experimental and clinical data, TMPRSS2:ERG-positive tumors may define a distinct subgroup of prostate cancers (8). Gene fusions involving ETS transcription factors are also present in other cancers. Notably, the ETS fusion EWS/FLI-1 occurs in 90% of Ewing sarcomas and is linked with increased IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) activity (10,11).

Given its influence on several hormonal pathways (5,6), obesity could potentially interact with TMPRSS2:ERG to differentially impact prostate cancer outcomes. In this study, we examined in a cohort of 1243 US men with prostate cancer whether the associations of body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and waist circumference with prostate cancer recurrence and death differ among men whose tumors overexpressed ERG [a marker of TMPRSS2:ERG (12)] compared with men whose tumors did not. We also explored whether tumor expression of key metabolic proteins IGF-1R, insulin receptor (IR), adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2), and fatty acid synthase (FASN) differs in ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors.

Methods

Study Cohort

The study consisted of men with prostate cancer enrolled in the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS), a randomized primary prevention trial of aspirin and supplements among 29067 US physicians followed with annual questionnaires since 1982 (13), or the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), a prospective study of causes of cancer and other diseases among 51529 US health professionals followed with biannual questionnaires since 1986 (14). All participants were initially free of diagnosed cancer except nonmelanoma skin cancer. Incident prostate cancers were confirmed through medical record review. The study was approved by institutional review boards at the Harvard School of Public Health and Partners Health Care. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

In both cohorts, archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded prostate tissues collected during radical prostatectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) were acquired from treating hospitals after informed consent. Study pathologists (R. T. Lis, R. Flavin, M. Fiorentino, S. Finn, and M. Loda) performed a standardized histopathological review that included uniform Gleason grading of hematoxylin and eosin slides from tumor blocks (15). Tissue microarrays were constructed from the archival materials with at least three 0.6-mm cores of tumor tissue per case from the primary tumor nodule or the nodule with the highest Gleason grade. The study included 1151 prostatectomy specimens and 92 TURP specimens.

Immunohistochemistry

We performed immunohistochemistry on 5-μm tissue microarray sections. A detailed description of the immunohistochemical methods is provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Tumors were classified as ERG-positive or -negative. IR, IGF-1R, and AdipoR2 receptor staining intensity was scored manually by the pathology team from 0 to 3. FASN expression intensity was scored quantitatively using image analysis from 0 to 255. For IR, IGF-1R, and AdipoR2, expression in tumor-adjacent “normal” prostate tissue was assessed in a subset of the samples. Proliferation was measured using the percentage of nuclei staining positive for Ki67, and apoptosis was measured using the TUNEL assay.

Anthropometric Measures

PHS participants provided weight and height at baseline in 1982, then weight again at 8 years follow-up and annually thereafter. Waist circumference was provided at 9 years follow-up. Weight at prostate cancer diagnosis has been collected through biannual questionnaires sent since 2000. HPFS participants provided weight and height in 1986 and weight information biannually thereafter. They provided waist circumference in 1987 and 1996. Self-reported weight and waist circumference values have previously been validated against technician-measured values in HPFS with Pearson correlations of 0.97 and 0.95, respectively (16).

As a measure of prediagnosis BMI (total obesity) and waist circumference (central obesity), we used anthropometric information from questionnaires returned closest to the prostate cancer diagnosis. BMI and waist circumference were measured on average 1.3 and 5.3 years before diagnosis, respectively. The Pearson correlation between BMI and waist circumference was 0.74. To minimize the risk of reverse causation, we also ran analyses using BMI information from the baseline questionnaires. BMI at baseline was measured on average 11.0 years before diagnosis. The Pearson correlation between BMI at baseline and prediagnosis BMI was 0.81.

Clinical Data

Information on tumor stage, prostate-specific antigen at diagnosis, and treatments was abstracted from medical records. Since 2000, prostate cancer patients have been followed for biochemical recurrence and development of metastatic disease through questionnaires. For HPFS participants, treating physicians were contacted to collect information about clinical course and to confirm development of metastases. For PHS participants, approximately 80% of participant-reported metastases were confirmed by medical record review, so we relied on self-report from the physician participants. Biochemical recurrence was participant or physician reported or abstracted from medical records and defined as prostate-specific antigen greater than 0.2ng/mL after surgery sustained over two measures. Study physicians assigned cause of death after a centralized review of medical records. Mortality follow-up is greater than 95%.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses included 1243 men (404 participants in PHS and 839 participants in HPFS) with a prediagnosis BMI between 18.5 and 50kg/m2. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between anthropometric measures and lethal prostate cancer (distant metastases or prostate cancer death) as well as biochemical and clinical recurrence (biochemical recurrence, lymph node metastases, distant metastases, or prostate cancer death). We tested the proportional hazard assumption in the main models (i.e., all models presented in Table 2) by creating interaction terms between BMI before diagnosis, waist circumference before diagnosis and BMI at baseline, respectively, and time since diagnosis in years, and we used Wald tests to assess their statistical significance. All P values were greater than .05, indicating that the proportional hazard assumption was met. Follow-up started on the date of prostate cancer diagnosis. Men were censored at death from other causes or at end of follow-up: March 2011 for PHS and December 2011 for HPFS. In both cohorts, because of questionnaire timing, follow-up for recurrence and metastases ended approximately 2 years before mortality follow-up. In sensitivity analyses, biochemical recurrence was the only outcome considered. We ran separate analyses only among men treated with prostatectomy, as prior data have suggested that the prevalence of TMPRSS2:ERG is lower in cancers identified in TURP vs prostatectomy tumor tissue and that TMPRSS2:ERG may be associated with poorer prognosis among men treated with noncurative intent but not among men treated with prostatectomy (17,18).

Table 2.

Anthropometric measures and hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for lethal prostate cancer (n = 119) among all men and by ERG tumor status among 1243 men with prostate cancer in the Physicians’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts

| Measures | All men | ERG negative | ERG positive | P interaction § | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | ||

| Body mass index before diagnosis, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5 to <25 | 56 | 7353 | Referent | Referent | 33 | 3407 | Referent | Referent | 23 | 3946 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25 to <27.5 | 34 | 5093 | 0.97(0.63 to 1.48) | 0.86(0.56 to 1.32) | 18 | 2734 | 0.77(0.43 to 1.38) | 0.65(0.36 to 1.17) | 16 | 2358 | 1.21(0.64 to 2.30) | 1.25(0.66 to 2.38) | |

| ≥27.5 | 29 | 3484 | 1.33(0.85 to 2.09) | 1.27(0.80 to 1.99) | 14 | 1833 | 0.97(0.52 to 1.80) | 0.96(0.51 to 1.80) | 15 | 1652 | 1.80(0.94 to 3.48) | 1.68(0.86 to 3.28) | |

| P trend║ | .27 | .43 | .78 | .67 | .08 | .13 | .38 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 119 | 15930 | 1.41(1.06 to 1.86) | 1.25(0.95 to 1.65) | 65 | 7974 | 1.21(0.81 to 1.79) | 1.10(0.76 to 1.59) | 54 | 7956 | 1.57(1.07 to 2.30) | 1.48(0.98 to 2.23) | .24 |

| Body mass index at baseline, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5 to <25 | 59 | 8370 | Referent | Referent | 36 | 3912 | Referent | Referent | 23 | 4458 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25 to <27.5 | 38 | 4909 | 1.09(0.72 to 1.63) | 1.17(0.78 to 1.76) | 21 | 2602 | 0.93(0.54 to 1.59) | 0.88(0.51 to 1.52) | 17 | 2307 | 1.35(0.72 to 2.54) | 1.71(0.91 to 3.24) | |

| ≥27.5 | 20 | 2433 | 1.07(0.64 to 1.77) | 0.88(0.53 to 1.47) | 7 | 1355 | 0.50(0.22 to 1.13) | 0.38(0.17 to 0.87) | 13 | 1078 | 2.19(1.11 to 4.32) | 2.08(1.04 to 4.17) | |

| P trend | .74 | .80 | .11 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .04 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 117 | 15712 | 1.34(0.98 to 1.84) | 1.15(0.84 to 1.56) | 64 | 7869 | 0.92(0.60 to 1.43) | 0.78(0.52 to 1.19) | 53 | 7843 | 2.17(1.35 to 3.50) | 2.22(1.35 to 3.63) | .001 |

| Waist circumference before diagnosis, in | |||||||||||||

| ≤37 in | 34 | 5900 | Referent | Referent | 20 | 2889 | Referent | Referent | 14 | 3011 | Referent | Referent | |

| ≤40 in | 30 | 3827 | 1.36(0.83 to 2.22) | 1.69(1.03 to 2.78) | 14 | 1787 | 1.25(0.63 to 2.47) | 2.05(0.99 to 4.25) | 16 | 2040 | 1.59(0.77 to 3.26) | 1.64(0.79 to 3.41) | |

| >40 in | 23 | 2844 | 1.59(0.93 to 2.70) | 1.83(1.05 to 3.18) | 12 | 1649 | 1.13(0.55 to 2.33) | 1.57(0.74 to 3.33) | 11 | 1196 | 2.37(1.07 to 5.24) | 2.26(0.98 to 5.21) | |

| P trend | .08 | .02 | .70 | .20 | .03 | .05 | .30 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 8 in | 87 | 12571 | 1.51(0.92 to 2.46) | 1.62(1.03 to 2.55) | 46 | 6324 | 0.94(0.48 to 1.84) | 1.14(0.62 to 2.10) | 41 | 6247 | 2.49(1.27 to 4.91) | 2.51(1.26 to 4.99) | .09 |

* Number of lethal events.

† For body mass index (BMI) before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and year of diagnosis (continuous). For BMI at baseline, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous).

‡ For BMI before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), clinical tumor stage (ordinal: T1/T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8). For BMI at baseline, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous), clinical tumor stage (ordinal: T1/T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8).

§ P interaction was tested by including an interaction term between BMI and waist circumference, respectively, and ERG tumor status in the multivariable models.

║ The median value of each BMI or waist circumference category was modeled as a continuous variable to test for evidence of linear trends across categories.

¶ Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

BMI and waist circumference were modeled as continuous variables (per 5-kg/m2 increments and per 8-in [20-cm] increments, respectively). Using linear regression, an 8-inch increase in waist circumference corresponded with a 5kg/m2 increase in BMI. We also modeled BMI and waist circumference categorically. Because few men (8%) were obese (BMI ≥30kg/m2), BMI was divided into the following categories: 18.5 to <25.0kg/m2 (normal weight), 25.0 to <27.5kg/m2 (preobese), and ≥27.5kg/m2 (preobese and obese) (19). Waist circumference was divided into ≤37 inches (≤94cm), 37 to ≤40 inches (94 to ≤102cm), and >40 inches (>102cm) (20). For prediagnosis BMI and waist circumference, we ran models adjusted for age and year of diagnosis. For BMI at baseline, we ran models adjusted for age at diagnosis and years between the baseline questionnaire and the date of diagnosis. We ran multivariable models additionally adjusted for tumor stage and Gleason score. Simple mean imputation was used for individuals missing clinical (n = 36) or pathological (n = 36) tumor stage.

The models above were run among all men and separately among men with ERG-negative and ERG-positive tumors. When BMI and waist circumference were continuous variables, the statistical interaction with ERG tumor status was tested by including an interaction term between BMI or waist circumference, respectively, and ERG tumor status and estimating the P value from the Wald test for the interaction term. When BMI and waist circumference were modeled as categorical variables, the median value of each BMI or waist circumference category was modeled as a continuous variable to test for evidence of linear trends across categories and was multiplied with ERG tumor status to create interaction terms. As a sensitivity analysis, we ran models excluding men with unknown clinical or pathological tumor stage. We also ran sensitivity analyses using competing risks regression (21), treating nonprostate cancer mortality as a competing event.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS institute, Cary, NC) and R free software version 2.15.0. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P values less than .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

The cohort was primarily white (92%), and the remaining men were 2% Asian, 1% black, and 5% other or unknown. The mean age at diagnosis was 66 years (range = 47–86). Mean prediagnosis BMI was 25.7kg/m2, mean prediagnosis waist circumference was 38.0 inches, and mean baseline BMI was 25.0kg/m2. ERG was overexpressed in half of the prostatectomy tumor specimens and in a quarter of the TURP tumor specimens (Table 1). Men with tumor tissue from TURP were generally older and had worse clinicopathologic features than men with prostatectomy tissue. Moreover, men with ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors had lower baseline BMI, lower TUNEL apoptosis index, and higher pathological stage.

Table 1.

Characteristics for all men and by ERG tumor status among 1243 men in the Physicians’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1982 to 2005*

| Characteristic | ERG tumor status assessed in radical prostatectomy | ERG tumor status assessed in transurethral resections of the prostate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.† | All men | ERG negative | ERG positive | P‡ | No.† | All men | ERG negative | ERG positive | P‡ | |

| Number (%) | 1151 | 1151 (100) | 576 (50) | 575 (50) | 92 | 92 (100) | 69 (75) | 23 (25) | ||

| Follow-up time, y, mean (SD) | 1151 | 13.0 (4.6) | 12.6 (4.3) | 13.4 (4.7) | <.01 | 92 | 10.1 (6.6) | 10.0 (6.2) | 10.2 (7.8) | .94 |

| Age at diagnosis, y, mean (SD) | 1151 | 65.5 (5.9) | 65.8 (5.8) | 65.1 (5.9) | .04 | 92 | 72.1 (6.3) | 72.5 (6.0) | 71.1 (7.1) | .37 |

| BMI before diagnosis, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 1151 | 25.7 (3.2) | 25.8 (3.1) | 25.5 (3.2) | .16 | 92 | 25.5 (3.0) | 25.5 (3.2) | 25.7 (2.2) | .78 |

| BMI at baseline, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 1135 | 25.0 (2.7) | 25.3 (2.8) | 24.8 (2.7) | <.01 | 91 | 25.1 (2.7) | 24.9 (2.9) | 25.7 (2.0) | .22 |

| Change in BMI between baseline and diagnosis, %, mean (SD) | 1135 | 2.6 (7.2) | 2.1 (6.3) | 3.0 (8.0) | .04 | 91 | 1.9 (9.2) | 2.6 (10.3) | -0.1 (2.1) | .22 |

| Waist circumference before diagnosis, inches, mean (SD) | 947 | 37.9 (3.5) | 38.1 (3.5) | 37.8 (3.5) | .25 | 58 | 39.0 (3.6) | 39.1 (4.0) | 38.8 (2.6) | .76 |

| PSA at diagnosis, median, ng/mL (q1, q3) | 1040 | 6.9 (4.8, 10.4) | 7.0 (5.0, 11.0) | 6.8 (4.6, 10.0) | .06 | 36 | 6.8 (3.9, 24.2) | 6.0 (3.8, 19.0) | 37.0 (10.0, 40.4) | .12 |

| Clinical tumor stage, No. (%) | 1116 | 91 | ||||||||

| T1/T2, Nx/N0 | 1061 (95) | 529 (95) | 532 (95) | 65 (71) | 55 (80) | 10 (45) | ||||

| T3, Nx/N0 | 43 (4) | 19 (3) | 24 (4) | 7 (8) | 3 (4) | 4 (18) | ||||

| T4, N1/M1 | 12 (1) | 8 (1) | 4 (1) | .73 | 19 (21) | 11 (16) | 8 (36) | .01 | ||

| Pathological tumor stage, No. (%) | 1115 | NA | ||||||||

| T2, Nx/N0 | 796 (71) | 413 (75) | 383 (68) | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| T3, Nx/N0 | 285 (26) | 128 (23) | 157 (28) | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| T4, N1/M1 | 34 (3) | 12 (2) | 22 (4) | .01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Gleason score, No. (%) | 1151 | 92 | ||||||||

| 4–6 | 245 (21) | 126 (22) | 119 (21) | 23 (25) | 20 (29) | 3 (13) | ||||

| 3+4 | 425 (37) | 197 (34) | 228 (40) | 22 (24) | 17 (25) | 5 (22) | ||||

| 4+3 | 267 (23) | 141 (24) | 126 (22) | 16 (17) | 9 (13) | 7 (30) | ||||

| 8–10 | 214 (19) | 112 (19) | 102 (18) | .42 | 31 (34) | 23 (33) | 8 (35) | .21 | ||

| Ki67 proliferation index, median, % (q1, q3) | 784 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.4) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.5) | .21 | 63 | 0.7 (0.0, 2.6) | 0.7 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.9 (0.3, 1.7) | .99 |

| TUNEL apoptosis index, median, % (q1, q3) | 659 | 0.5 (0.0, 2.0) | 0.5 (0.5, 3.0) | 0.5 (0.0, 2.0) | <.01 | 34 | 0.5 (0.5, 2.0) | 0.5 (0.5, 3.5) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.5) | .01 |

* BMI = body mass index; NA = not applicable; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; q1 = lower quartile; q3 = upper quartile; SD = standard deviation.

† Number of men with data available on the respective characteristic.

‡ P values are based on the t test for follow-up time, age at diagnosis, BMI before diagnosis, BMI at baseline, and waist circumference before diagnosis; the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for PSA at diagnosis, Ki67 proliferation index, and TUNEL apoptosis index; and the Cochran–Armitage trend test for clinical tumor stage, pathological tumor stage, and Gleason score. All statistical tests were two-sided.

During a mean of 12.8 years of follow-up, 96 men died of prostate cancer, and an additional 23 men developed distant metastases. In the simple models, the hazard ratio for lethal prostate cancer among all men was 1.41 (95% CI = 1.06 to 1.86) per 5-kg/m2 increase in prediagnosis BMI, 1.51 (95% CI = 0.92 to 2.46) per 8-inch increase in prediagnosis waist circumference, and 1.34 (95% CI = 0.98 to 1.84) per 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI at baseline. The corresponding hazard ratios were 1.57 (95% CI = 1.07 to 2.30), 2.49 (95% CI = 1.27 to 4.91), and 2.17 (95% CI = 1.35 to 3.50) among men with ERG-positive tumors and 1.21 (95% CI = 0.81 to 1.79), 0.94 (95% CI = 0.48 to 1.84), and 0.92 (95% CI = 0.60 to 1.43) among men with ERG-negative tumors. These associations were somewhat attenuated in multivariable models additionally adjusted for tumor stage and grade (ERG-positive tumors: HR for lethal prostate cancer = 1.48, 95% CI = 0.98 to 2.23 per 5-unit increase in BMI before diagnosis; HR = 2.51, 95% CI = 1.26 to 4.99 per 8-inch increase in waist circumference before diagnosis; and HR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.35 to 3.63 per 5-unit increase in BMI at baseline; ERG-negative tumors: HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.76 to 1.59 per 5-unit increase in BMI before diagnosis; HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.62 to 2.10 per 8-inch increase in waist circumference before diagnosis; and HR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.19 per 5-unit increase in BMI at baseline) (Table 2). P values for interaction between anthropometric measures and ERG tumor status were .24 for prediagnosis BMI, .09 for prediagnosis waist circumference, and .001 for baseline BMI in multivariable models. Findings were similar in analyses restricted to men treated with prostatectomy (Table 3). Although the risk estimates were generally smaller, similar patterns were seen when the outcomes were biochemical and clinical recurrence (Table 4) or biochemical recurrence alone (data not shown). Excluding men with unknown clinical or pathological tumor stage did not materially change the results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Anthropometric measures and hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for lethal prostate cancer (n = 84) among all men and by ERG tumor status among 1151 men with prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy in the Physicians’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts

| Measures | All men | ERG negative | ERG positive | P interaction § | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | ||

| Body mass index before diagnosis, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5 to <25 | 41 | 6931 | Referent | Referent | 21 | 3071 | Referent | Referent | 20 | 3860 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25 to <27.5 | 24 | 4709 | 0.95(0.57 to 1.57) | 0.82(0.49 to 1.36) | 13 | 2467 | 0.84(0.42 to 1.67) | 0.60(0.30 to 1.21) | 11 | 2242 | 1.01(0.48 to 2.12) | 1.00(0.47 to 2.11) | |

| ≥27.5 | 19 | 3364 | 1.11(0.65 to 1.92) | 1.08(0.63 to 1.88) | 9 | 1744 | 0.86(0.39 to 1.89) | 0.77(0.35 to 1.69) | 10 | 1620 | 1.33(0.62 to 2.85) | 1.36(0.62 to 2.99) | |

| P trend║ | .75 | .92 | .66 | .40 | .50 | .49 | .77 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 84 | 15003 | 1.35(0.97 to 1.89) | 1.27(0.90 to 1.79) | 43 | 7281 | 1.13(0.67 to 1.89) | 1.03(0.63 to 1.68) | 41 | 7722 | 1.48(0.96 to 2.27) | 1.51(0.94 to 2.43) | .15 |

| Body mass index at baseline, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5-<25 | 42 | 7929 | Referent | Referent | 21 | 3503 | Referent | Referent | 21 | 4425 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25-<27.5 | 28 | 4541 | 1.21(0.75 to 1.95) | 1.24(0.77 to 2.00) | 16 | 2395 | 1.13(0.59 to 2.17) | 0.91(0.47 to 1.75) | 12 | 2146 | 1.21(0.60 to 2.47) | 1.42(0.69 to 2.93) | |

| ≥27.5 | 13 | 2324 | 1.01(0.54 to 1.88) | 0.89(0.48 to 1.66) | 5 | 1278 | 0.57(0.21 to 1.52) | 0.38(0.14 to 1.02) | 8 | 1046 | 1.58(0.70 to 3.58) | 1.72(0.75 to 3.95) | |

| P trend | .81 | .93 | .37 | .07 | .26 | .17 | .40 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 83 | 14794 | 1.48(1.03 to 2.14) | 1.36(0.95 to 1.94) | 42 | 7176 | 1.03(0.61 to 1.77) | 0.85(0.50 to 1.46) | 41 | 7617 | 2.14(1.26 to 3.63) | 2.21(1.29 to 3.80) | .01 |

| Waist circumference before diagnosis, in | |||||||||||||

| ≤37 in | 27 | 5709 | Referent | Referent | 15 | 2722 | Referent | Referent | 12 | 2987 | Referent | Referent | |

| ≤40 in | 21 | 3649 | 1.30(0.73 to 2.30) | 1.47(0.82 to 2.61) | 10 | 1691 | 1.25(0.56 to 2.79) | 1.69(0.74 to 3.85) | 11 | 1958 | 1.47(0.64 to 3.35) | 1.54(0.66 to 3.59) | |

| >40 in | 16 | 2655 | 1.50(0.81 to 2.79) | 1.91(1.01 to 3.61) | 8 | 1471 | 1.09(0.46 to 2.58) | 1.35(0.57 to 3.23) | 8 | 1184 | 1.96(0.80 to 4.84) | 2.53(0.98 to 6.54) | |

| P trend | .18 | .04 | .80 | .42 | .13 | .05 | .22 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 8 in | 64 | 12013 | 1.48(0.84 to 2.62) | 1.91(1.08 to 3.40) | 33 | 5885 | 0.86(0.38 to 1.95) | 1.11(0.49 to 2.53) | 31 | 6129 | 2.27(1.07 to 4.83) | 2.88(1.29 to 6.43) | .06 |

* Number of lethal events.

† For body mass index (BMI) before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and year of diagnosis (continuous). For BMI at baseline, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous).

‡ For BMI before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), pathological tumor stage (ordinal: T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8). For BMI at baseline, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous), pathological tumor stage (ordinal: T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8).

§ P interaction was tested by including an interaction term between BMI and waist circumference, respectively, and ERG tumor status in the multivariable models.

║ The median value of each BMI or waist circumference category was modeled as a continuous variable to test for evidence of linear trends across categories.

¶ Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Table 4.

Anthropometric measures and hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for biochemical and clinical recurrence (n = 266) among all men and by ERG tumor status among 1151 men with prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy in the Physicians’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts

| Measures | All men | ERG negative | ERG positive | P interaction § | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | No.* | Person- years | HR (95% CI) for Model 1† | HR (95% CI) for Model 2‡ | ||

| Body mass index before diagnosis, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5 to <25 | 117 | 6084 | Referent | Referent | 61 | 2660 | Referent | Referent | 56 | 3424 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25 to <27.5 | 88 | 3976 | 1.18(0.89 to 1.55) | 1.13(0.86 to 1.49) | 44 | 2084 | 0.96(0.65 to 1.41) | 0.89(0.61 to 1.32) | 44 | 1891 | 1.39(0.94 to 2.07) | 1.35(0.91 to 2.02) | |

| ≥27.5 | 61 | 2889 | 1.15(0.84 to 1.56) | 1.05(0.77 to 1.43) | 29 | 1513 | 0.92(0.59 to 1.43) | 0.83(0.53 to 1.29) | 32 | 1376 | 1.42(0.92 to 2.19) | 1.32(0.85 to 2.06) | |

| P trend║ | .33 | .68 | .69 | .39 | .09 | .17 | .36 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 266 | 12949 | 1.21(1.01 to 1.46) | 1.13(0.94 to 1.37) | 134 | 6257 | 1.04(0.78 to 1.37) | 0.96(0.74 to 1.26) | 132 | 6692 | 1.37(1.08 to 1.74) | 1.32(1.03 to 1.71) | .06 |

| Body mass index at baseline, kg/m2 | |||||||||||||

| 18.5-<25 | 124 | 7024 | Referent | Referent | 61 | 3106 | Referent | Referent | 63 | 3919 | Referent | Referent | |

| 25-<27.5 | 89 | 3856 | 1.30(0.99 to 1.71) | 1.23(0.94 to 1.62) | 49 | 1988 | 1.27(0.87 to 1.85) | 1.10(0.75 to 1.61) | 40 | 1868 | 1.29(0.87 to 1.92) | 1.30(0.87 to 1.94) | |

| ≥27.5 | 49 | 1878 | 1.35(0.97 to 1.88) | 1.28(0.92 to 1.78) | 23 | 1059 | 1.02(0.63 to 1.66) | 0.89(0.55 to 1.45) | 26 | 819 | 1.77(1.12 to 2.80) | 1.77(1.12 to 2.80) | |

| P trend | .04 | .10 | .70 | .76 | .01 | .02 | .09 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 5kg/m2 | 262 | 12758 | 1.35(1.09 to 1.66) | 1.25(1.02 to 1.53) | 133 | 6152 | 1.13(0.85 to 1.52) | 1.02(0.77 to 1.35) | 129 | 6606 | 1.63(1.20 to 2.21) | 1.54(1.14 to 2.09) | .04 |

| Waist circumference before diagnosis, in | |||||||||||||

| ≤37 in | 108 | 4844 | Referent | Referent | 61 | 2234 | Referent | Referent | 47 | 2611 | Referent | Referent | |

| ≤40 in | 61 | 3145 | 0.91(0.66 to 1.24) | 0.95(0.70 to 1.31) | 23 | 1520 | 0.60(0.37 to 0.96) | 0.63(0.39 to 1.02) | 38 | 1624 | 1.30(0.84 to 2.00) | 1.37(0.89 to 2.12) | |

| >40 in | 50 | 2284 | 1.03(0.73 to 1.44) | 1.07(0.76 to 1.50) | 27 | 1246 | 0.82(0.52 to 1.29) | 0.84(0.53 to 1.32) | 23 | 1038 | 1.28(0.78 to 2.12) | 1.43(0.86 to 2.38) | |

| P trend | .97 | .75 | .27 | .31 | .27 | .13 | .10 | ||||||

| Continuous, per 8 in | 219 | 10273 | 0.99(0.72 to 1.35) | 1.07(0.79 to 1.45) | 111 | 5000 | 0.69(0.44 to 1.08) | 0.75(0.48 to 1.16) | 108 | 5273 | 1.39(0.90 to 2.14) | 1.55(1.01 to 2.38) | 0.02 |

* Number of biochemical and clinical recurrences.

† For body massindex (BMI) before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and year of diagnosis (continuous). For BMI at baseline, Model 1 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), and years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous).

‡ For BMI before diagnosis and for waist circumference before diagnosis, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), pathological tumor stage (ordinal: T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8). For BMI at baseline, Model 2 is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), years between baseline and diagnosis (continuous), pathological tumor stage (ordinal: T2,NX/N0, T3,NX/N0, T4,N1/M1) and Gleason score (ordinal: ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, ≥8).

§ P interaction was tested by including an interaction term between BMI and waist circumference, respectively, and ERG tumor status in the multivariable models.

║ The median value of each BMI or waist circumference category was modeled as a continuous variable to test for evidence of linear trends across categories.

¶ Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

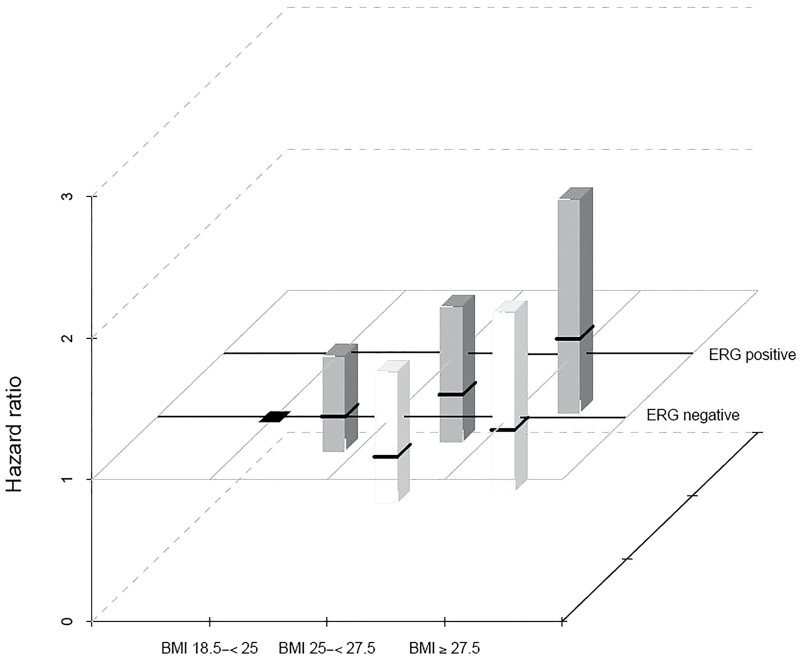

We examined the association between categories of prediagnosis BMI and lethal prostate cancer stratified by ERG status using normal-weight men with ERG-negative tumors as the reference category (Figure 1). In this analysis, normal-weight men with ERG-positive tumors had a 40% decreased risk of lethal prostate cancer (HR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.35 to 1.03). The hazard ratio among men with ERG-negative tumors and BMI ≥27.5kg/m2 was 0.95 (95% CI = 0.51 to 1.78), and the hazard ratio among men with ERG-positive tumors and BMI ≥27.5kg/m2 was 1.15 (95% CI = 0.62 to 2.13) (P interaction = .24). Among men treated with prostatectomy, the overall multivariable hazard ratio of lethal disease among men with ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors was 0.83 (95% CI = 0.54 to 1.29).

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios (HR) for lethal prostate cancer by cross-classified categories of body mass index (BMI) and ERG tumor status. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models and are represented by black squares. Men with ERG-negative tumors and BMI of 18.5 to <25kg/m2 is the reference category. Column heights represent the 95% confidence intervals.

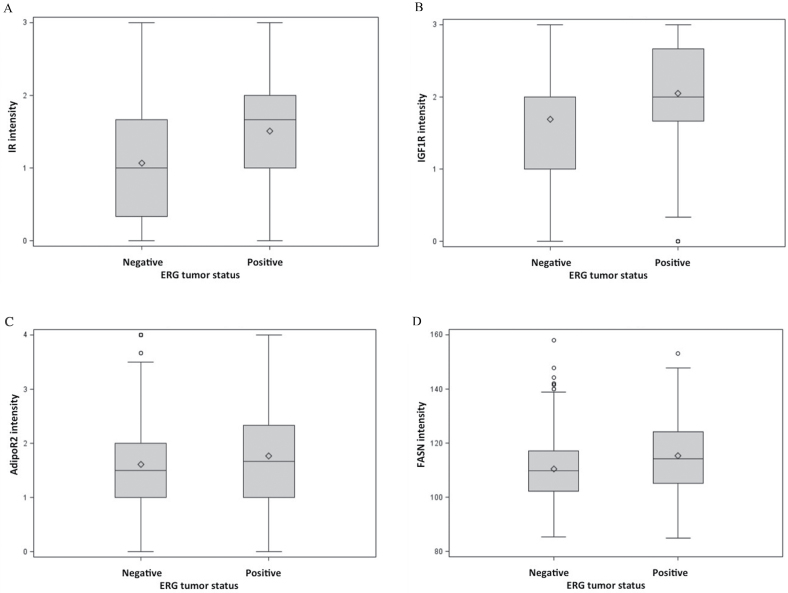

The expression of IR, IGF1-R, AdipoR2, and FASN were statistically significantly (Ps < .01) higher in ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors (Figure 2, A–D). IR, IGF-1R, and AdipoR2 expression were higher in tumor tissue than tumor-adjacent normal tissue; the expression of these proteins in normal tissue did not differ by ERG tumor status (data not shown). There were no statistically significant correlations between anthropometric measures and marker expression in tumor or normal tissue (data not shown). Among men with ERG-positive tumors, adjustment for these four markers did not attenuate the association between prediagnosis BMI and lethal disease or biochemical and clinical recurrence (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Distributions of tumor protein expression intensity by ERG tumor status. A) Insulin receptor (IR). B) IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R). C) Adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2). D) Fatty acid synthase (FASN).

In sensitivity analyses using competing risks regression, results were similar to those from the standard Cox regressions. Among men with ERG-positive tumors, the multivariable hazard ratio for lethal prostate cancer was 1.38 (95% CI = 0.93 to 2.04) per 5-kg/m2 increase in prediagnosis BMI, 2.07 (95% CI = 1.01 to 4.23) per 8-inch increase in prediagnosis waist circumference, and 1.89 (95% CI = 1.18 to 3.04) per 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI at baseline. The corresponding hazard ratios among men with ERG-negative tumors were 1.09 (95% CI = 0.79 to 1.51), 0.98 (95% CI = 0.60 to 1.60), and 0.77 (95% CI = 0.49 to 1.21).

Discussion

In this large, prospective study of prostate cancer patients, we observed statistically significant or borderline statistically significant positive associations between both total and central obesity measures before diagnosis and risk of prostate cancer recurrence and death among men with ERG-positive tumors but not among men with ERG-negative tumors. Moreover, ERG-positive tumors were characterized by higher expression of IR, IGF-1R, AdipoR2, and FASN compared with ERG-negative tumors. The findings suggest that ERG-positive tumors are characterized by altered metabolic signaling pathways and that obesity interacts with ERG tumor status to influence prostate cancer outcomes.

Although the interactions between obesity measures and ERG tumor status were mostly non-statistically significant, the trends suggest that 1) excess bodyweight is associated with poorer prognosis primarily in men with ERG-positive tumors, 2) the prognostic utility of ERG tumor status depends on the bodyweight of the patient/study cohort, and 3) the association between bodyweight and prostate cancer outcome depends on the prevalence of ERG tumor status of the study cohort, which varies by, for example, ethnicity (18). ERG-positive status vs ERG-negative status would be associated with a favorable prognosis among normal-weight men, no substantial difference in prognosis among moderately overweight men, and poorer prognosis among obese men. We also observed that among both all men and men with ERG-positive tumors, waist circumference increased risk of lethal prostate more than BMI before diagnosis did. This may be because waist circumference is a more accurate measure of adiposity in older men or because the primary drivers of lethal prostate cancer are linked more strongly with central than total adiposity.

We observed higher IR and IGF-1R expression in ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors. In Ewing sarcomas, the EWS/FLI-1 gene fusion upregulates IGF-1 and IGF1-R and downregulates IGF binding protein 3 by directly or indirectly targeting the expression of these genes (10,11,22). Similar mechanisms may cause upregulation of IGF-1R in ERG-positive prostate tumors. IR and IGF-1R signaling leads to activation of cancer-relevant pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, and PI3K pathway activation cooperates with TMPRSS2:ERG in mouse models to promote prostate tumorigenesis (23–25). Higher IGF-1R and IR expression in ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors suggests a mechanism by which obesity, through higher circulating levels of insulin and free IGF-1, could be associated with disease progression primarily among men with ERG-positive tumors. FASN facilitates de novo syntheses of fatty acids (26). It is overexpressed in many cancers, including prostate cancer, where it can act as an oncogene (27). We found a slightly higher expression of FASN in ERG-positive vs ERG-negative tumors, which may partly explain the positive association between BMI and waist circumference and risk of lethal prostate cancer among men with ERG-positive tumors. We have previously reported that high FASN tumor expression is associated with an increased risk of lethal prostate cancer among overweight men but not among normal weight men (28). Similar findings of an interaction between BMI and FASN expression and cancer mortality have been found in colorectal cancer patients, and it has been speculated that colon tumor cells with upregulated FASN depend on excess energy for growth, leading to a more aggressive behavior among obese patients (29). It should be noted, however, that the association between BMI before diagnosis and cancer outcomes among men with ERG-positive tumors was not attenuated after adjustment for IR, IGF1-R, AdipoR2, and FASN, arguing somewhat against the hypothesis that the expression of these markers explains the association between BMI and cancer outcomes among men with ERG-positive tumors.

The effect of obesity on prostate cancer outcomes could also differ by ERG tumor status because of obesity-related alterations of circulating sex hormone levels because ERG expression is regulated by androgens and possibly estrogens (9). Furthermore, obesity is associated with lifestyle, dietary, and perhaps therapeutic-related factors (30) that may partly explain an association between obesity and poor prostate cancer outcomes. In addition, the association between BMI at baseline and cancer outcomes among men with ERG-positive tumors was generally stronger than for BMI before diagnosis in this study, suggesting that obesity many years before diagnosis may affect tumor aggressiveness and that prostate tumors developing in the hormonal environment of overweight or obese men may have innately poorer prognosis. Additional studies are needed to address the mechanisms by which obesity may be associated with poorer prognosis in patients with ERG-positive tumors.

Strengths of this study include its large sample size, long follow-up, validated data on anthropometric measures, and well-defined lethal prostate cancer outcomes. Still, a limitation is the relatively small number of events, which underscores the importance of replicating the study findings in large, independent cohorts. Another limitation of this study is that we defined TMPRSS2:ERG status by immunohistochemistry. Approximately 10% of prostate tumors harbor gene fusions involving an ETS transcription factor other than ERG (8). If the family of ETS fusions, rather than only ERG per se, defines a molecular subgroup of prostate cancers that interacts with obesity to impact progression, our risk estimates could have been biased among men with ERG-negative tumors.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the detrimental effects of obesity on prostate cancer outcomes are limited primarily to men with tumors harboring the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion. If confirmed, this finding advances the understanding of the molecular factors linking obesity and prostate cancer outcome and could potentially inform prostate cancer therapy development and secondary prevention strategies.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Specialized Programs of Research Excellence program in prostate cancer (5P50CA090381-08); the National Cancer Institute (T32 CA009001 to KLP; R25 CA098566 to REG; CA55075, CA141298, CA13389, CA-34944, CA-40360, CA-097193, EDRN U01 CA113913, and PO1 CA055075); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-26490 and HL-34595); the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to LAM, KLP, and NEM); the Swedish Research Council (Reg. No. 2009–7309 to AP), and the Royal Physiographic Society in Lund (to AP).

Supplementary Material

We are grateful to the participants and staff of the Physicians’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study for their valuable contributions. In addition we would like to thank the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Tissue Microarray Core Facility constructed the tissue microarrays in this project, and we would like to thank Chungdak Li for her expert tissue microarray construction.

References

- 1. Cao Y, Ma J. Body mass index, prostate cancer-specific mortality, and biochemical recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(4):486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ma J, Li H, Giovannucci E, et al. Prediagnostic body-mass index, plasma C-peptide concentration, and prostate cancer-specific mortality in men with prostate cancer: a long-term survival analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(11):1039–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(8):579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hursting SD, Berger NA. Energy balance, host-related factors, and cancer progression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(26):4058–4065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubin MA, Maher CA, Chinnaiyan AM. Common gene rearrangements in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3659–3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Setlur SR, Mertz KD, Hoshida Y, et al. Estrogen-dependent signaling in a molecularly distinct subclass of aggressive prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(11):815–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackintosh C, Madoz-Gurpide J, Ordonez JL, Osuna D, Herrero-Martin D. The molecular pathogenesis of Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9(9):655–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ho AL, Schwartz GK. Targeting of insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor in Ewing sarcoma: unfulfilled promise or a promising beginning? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(34):4581–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaux A, Albadine R, Toubaji A, et al. Immunohistochemistry for ERG expression as a surrogate for TMPRSS2-ERG fusion detection in prostatic adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(7):1014–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hennekens CH, Eberlein K. A randomized trial of aspirin and beta-carotene among U.S. physicians. Prev Med. 1985;14(2):165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Platz EA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Risk factors for prostate cancer incidence and progression in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(7):1571–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stark JR, Perner S, Stampfer MJ, et al. Gleason score and lethal prostate cancer: does 3 + 4 = 4 + 3? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3459–3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1(6):466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Demichelis F, Fall K, Perner S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion associated with lethal prostate cancer in a watchful waiting cohort. Oncogene. 2007;26(31):4596–4599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pettersson A, Graff RE, Bauer SR, et al. The TMPRSS2:erg rearrangement, erg expression, and prostate cancer outcomes: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(9):1497–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Global Database on Body Mass Index. Available at: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html Accessed November 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKinsey EL, Parrish JK, Irwin AE, et al. A novel oncogenic mechanism in Ewing sarcoma involving IGF pathway targeting by EWS/Fli1-regulated microRNAs. Oncogene. 2011;30(49):4910–4920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. King JC, Xu J, Wongvipat J, et al. Cooperativity of TMPRSS2-ERG with PI3-kinase pathway activation in prostate oncogenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):524–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zong Y, Xin L, Goldstein AS, Lawson DA, Teitell MA, Witte ON. ETS family transcription factors collaborate with alternative signaling pathways to induce carcinoma from adult murine prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(30):12465–12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carver BS, Tran J, Gopalan A, et al. Aberrant ERG expression cooperates with loss of PTEN to promote cancer progression in the prostate. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):619–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):763–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Migita T, Ruiz S, Fornari A, et al. Fatty acid synthase: a metabolic enzyme and candidate oncogene in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(7):519–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen PL, Ma J, Chavarro JE, et al. Fatty acid synthase polymorphisms, tumor expression, body mass index, prostate cancer risk, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):3958–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ogino S, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Cohort study of fatty acid synthase expression and patient survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5713–5720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keto CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, et al. Obesity is associated with castration-resistant disease and metastasis in men treated with androgen deprivation therapy after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. BJU Int. 2012;110 (4):492–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.