Abstract

SH2B1 is an SH2 and PH domain-containing adaptor protein. Genetic deletion of SH2B1 results in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver diseases in mice. Mutations in SH2B1 are linked to obesity in humans. SH2B1 in the brain controls energy balance and body weight at least in part by enhancing leptin sensitivity in the hypothalamus. SH2B1 in peripheral tissues also regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, presumably by enhancing insulin sensitivity in peripheral metabolically-active tissues. However, the function of SH2B1 in individual peripheral tissues is unknown. Here we generated and metabolically characterized hepatocyte-specific SH2B1 knockout (HKO) mice. Blood glucose and plasma insulin levels, glucose tolerance, and insulin tolerance were similar between HKO, albumin-Cre, and SH2B1f/f mice fed either a normal chow diet or a high fat diet (HFD). Adult-onset deletion of SH2B1 in the liver either alone or in combination with whole body SH2B2 knockout also did not exacerbate HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. Adult-onset, but not embryonic, deletion of SH2B1 in the liver attenuated HFD-induced hepatic steatosis. In agreement, adult-onset deletion of hepatic SH2B1 decreased the expression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2) and increased the expression of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL). Furthermore, deletion of liver SH2B1 in SH2B2 null mice attenuated very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion. These data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is not required for the maintenance of normal insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism; however, it regulates liver triacylglycerol synthesis, lipolysis, and VLDL secretion.

Introduction

The liver is an essential metabolic organ which produces glucose through both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. During fasting, liver-produced glucose provides an essential metabolic fuel for extrahepatic tissues, including red blood cells and the brain, to meet their metabolic demands. In the fed state, insulin is released from pancreatic β cells and suppresses hepatic glucose production, thus maintaining blood glucose levels within a narrow arrange during fasting-feeding cycles. In type 2 diabetes, the ability of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose production is impaired (referred to hepatic insulin resistance), so the liver produces excessive glucose, contributing to hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance [1]. In contrast, glucagon and other counterregulatory hormones stimulate hepatic glucose production to increase blood glucose levels. Aberrant hyperglycemic responses to counterregulatory hormones may also contribute to hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in obesity and type 2 diabetes [2].

Obesity prevalence has increased rapidly. Obesity is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [3]. The liver plays a critical role in lipid metabolism. During fasting, adipose tissue releases free fatty acids which are taken up by hepatocytes and converted into ketone bodies. Ketone bodies serve as a major metabolic fuel for extrahepatic tissues in the fasted state. When carbohydrates are abundant, the liver converts glucose into fatty acids which are used to synthesize triacylglycerol (TAG). TAG is packaged into very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles which deliver lipids (i.e. fatty acids and cholesterol) to extrahepatic tissues through the circulation [4]. Abnormal VLDL secretion is a risk factor for atherosclerosis [5]. Alternatively, TAG is stored in lipid droplets within hepatocytes, or is used as an intracellular energy source. Hepatic steatosis is a key risk factor for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [3], [6], [7]. Increased lipid content reduces hepatocyte viability and increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in hepatocytes [8]. Additionally, abnormal lipid accumulation impairs insulin sensitivity in the liver, contributing to increased hepatic glucose production, hyperglycemia, and glucose intolerance in obesity-associated type 2 diabetes [9].

The SH2B family contains three members of adaptor proteins (SH2B1, 2 and 3) [10]. SH2B1 and SH2B2 are ubiquitously expressed, and SH2B3 expression is restricted to the immune system [11]–[13]. SH2B1 directly binds to JAK2 and stimulates JAK2 activity, thereby enhancing JAK2 signaling in response to growth hormone, leptin, erythropoietin, and prolactin [11], [14]–[17]. SH2B1 also binds to IRS1 and IRS2 and enhances IRS protein-mediated activation of the PI 3-kinase pathway in response to leptin, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor -1 [18]–[20]. SH2B1 was also reported to mediate cell signaling in response to fibroblast growth factor, nerve growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor [21]–[24]. Genetic disruption of the SH2B1 gene results in severe leptin resistance, insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and NAFLD in mice [25], [26]. We previously reported that neuron-specific restoration of SH2B1β transgenes (Tg) into SH2B1 knockout (KO) mice (called TgKO mice) fully corrects leptin resistance, hyperphagia, and obesity in TgKO mice [27]. SH2B1 directly enhances leptin signaling in cultured cells [14], [18]; therefore, neuronal SH2B1 exerts anti-obesity action at least in part by enhancing leptin sensitivity. Importantly, the metabolic function of SH2B1 is evolutionarily conserved. Deletion of drosophila SH2B results in obesity phenotypes in flies [28], [29]. Many SH2B1 SNPs and missense SH2B1 mutations have been reported to be linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes in humans [30]-[34].

We have reported that TgKO mice, which lack SH2B1 only in peripheral tissues, have normal body weight, but they are still predisposed to high fat diet (HFD)-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [19], [20]. These observations raise the possibility that peripheral SH2B1 may also regulate insulin sensitivity and nutrient metabolism. In agreement, we recently reported that pancreas-specific deletion of SH2B1 impairs HFD-induced cell expansion, thereby reducing insulin secretion capacity [35]. In this study, we examined the function of SH2B1 in the liver by generating and characterizing hepatocyte-specific SH2B1 knockout (HKO) mice. We observed that HKO mice have relatively normal insulin sensitivity, body weight, and glucose metabolism. However, both liver lipid levels and VLDL secretion are lower in HFD-fed mice with adult-onset deletion of SH2B1 in the liver.

Results

Deletion of SH2B1 in peripheral tissues promotes hepatic steatosis

TgKO mice, which lack endogenous SH2B1 but express rat SH2B1β transgenes under the control of the neuron-specific enolase promoter, were generated and verified previously [27]. SH2B1 protein was detected in the brain but not in peripheral tissues [27]. We have reported that TgKO mice are more prone to HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [20]. To determine whether SH2B1 deficiency in peripheral tissues promotes NAFLD, TgKO male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 16 weeks. Both body weight (Fig. 1A) and fat content (TgKO: 36.6%, n = 7; WT: 38.0%, n = 9; p = 0.54) were similar between TgKO and wild type (WT) mice. The sizes of individual white adipocytes were also similar between TgKO and WT mice (Fig. 2B). By contrast, liver TAG levels were 66% higher in TgKO mice than in WT mice (Fig. 1C). The livers of TgKO mice had larger lipid droplets as revealed by H & E staining of liver sections (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that peripheral SH2B1 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism independently of its action on body weight.

Figure 1. Deletion of SH2B1 in peripheral tissues augments HFD-induced hepatic steatosis.

Male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 16 weeks. (A) Fasting body weight. WT: n = 9, TgKO: n = 7. (B) A representative H & E staining of epididymal fat depots. (C) Liver TAG levels (normalized to liver weight). WT: n = 6; TgKO: n = 6. (D) A representative H & E staining of liver sections. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

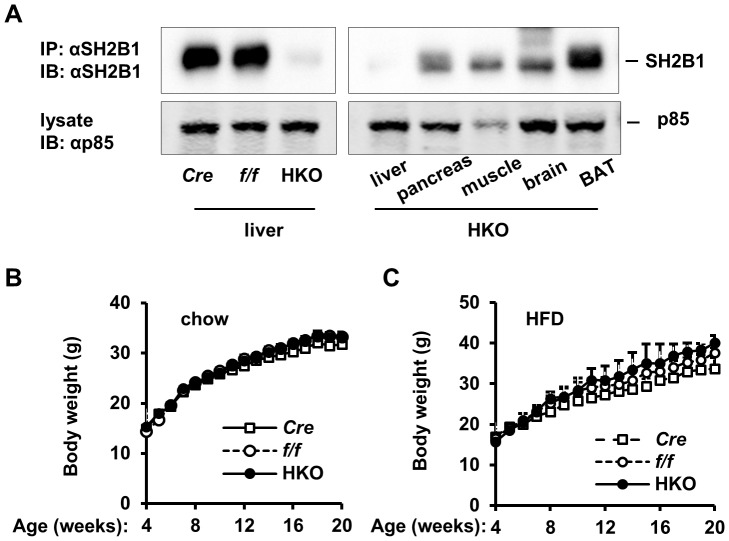

Figure 2. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not increase body weight.

(A) Tissue extracts were prepared from the indicated male mice (7 weeks of age) and immunoprecipitated (IP) and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-SH2B1 antibody (upper panels). Tissue extracts were also directly immunoblotted with antibody against the p85 subunit of the PI 3-kinase (lower panels). (B) Growth curves of male mice fed a normal chow diet. f/f: n = 9; Cre: n = 5; HKO: n = 9. (C) Growth curves of male mice were fed a HFD (from 7–20 weeks of age). f/f: n = 5; Cre: n = 5; HKO: n = 6. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

Liver-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not increase HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance

To determine whether hepatic SH2B1 regulates glucose metabolism, we generated HKO mice using the albumin-Cre/loxp system. SH2B1 protein was abundant in the livers of both albumin-Cre and SH2B1f/f mice, but barely detectable in the livers of HKO mice (Fig. 2A). In HKO mice, SH2B1 expression was normal in the pancreas, skeletal muscle, brain, and brown adipose tissue (BAT) (Fig. 2A). HKO mice were grossly normal, and growth curves were similar between albumin-Cre, SH2B1f/f, and HKO mice (Fig. 2B), indicating that hepatic SH2B1 is unlikely to mediate the effect of growth hormone on promoting somatic growth. Liver-specific deletion of SH2B1 also did not affect HFD-induced obesity in HKO mice (Fig. 2C).

We metabolically characterized HKO mice using multiple approaches. Fasting blood glucose levels and plasma insulin concentrations were comparable between albumin-Cre, SH2B1f/f, and HKO mice (Fig. 3A). In insulin tolerance tests (ITT), exogenous insulin similarly decreased blood glucose in albumin-Cre, SH2B1f/f, and HKO mice (Fig. 3B). In glucose tolerance tests (GTT), glucose injection increased blood glucose to comparable levels among these three genotypes (Fig. 3C). To estimate hepatic glucose production, we performed pyruvate tolerance tests (PTT). Administration of pyruvate, a gluconeogenic precursor, increased blood glucose to a similar extent between these three groups (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not exacerbate HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

(A-D) Mice were fed a normal chow diet. (A) Overnight fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels (18 weeks of age). f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 9; HKO: n = 10. (B) ITT was performed on male mice at 18 weeks of age (insulin: 1 unit/kg body weight). f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 7; HKO: n = 10. (C) GTT was performed on male mice at 19 weeks of age (D-glucose: 2 g/kg body weight). f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 7; HKO: n = 10. (D) PTT was performed on mice at 19 weeks of age (pyruvate: 2 g/kg body weight). f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 7; HKO: n = 10. (E-H) Mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD. f/f: n = 9; Cre: n = 6; HKO: n = 8. (E) Overnight fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin (HFD for 11 weeks). (F) ITT (HFD for 11 weeks). (G) GTT (HFD for 12 weeks). D-glucose: 1 g/kg body weight. (H) PTT (HFD for 12 weeks). Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

To determine whether hepatic SH2B1 is involved in HFD-induced insulin resistance, we fed HKO and control male mice a HFD. Overnight fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were similar between albumin-Cre, SH2B1f/f, and HKO mice (Fig. 3E). Insulin tolerance (Fig. 3F), glucose tolerance (Fig. 3G), and pyruvate tolerance (Fig. 3H) were also indistinguishable between these three genotypes.

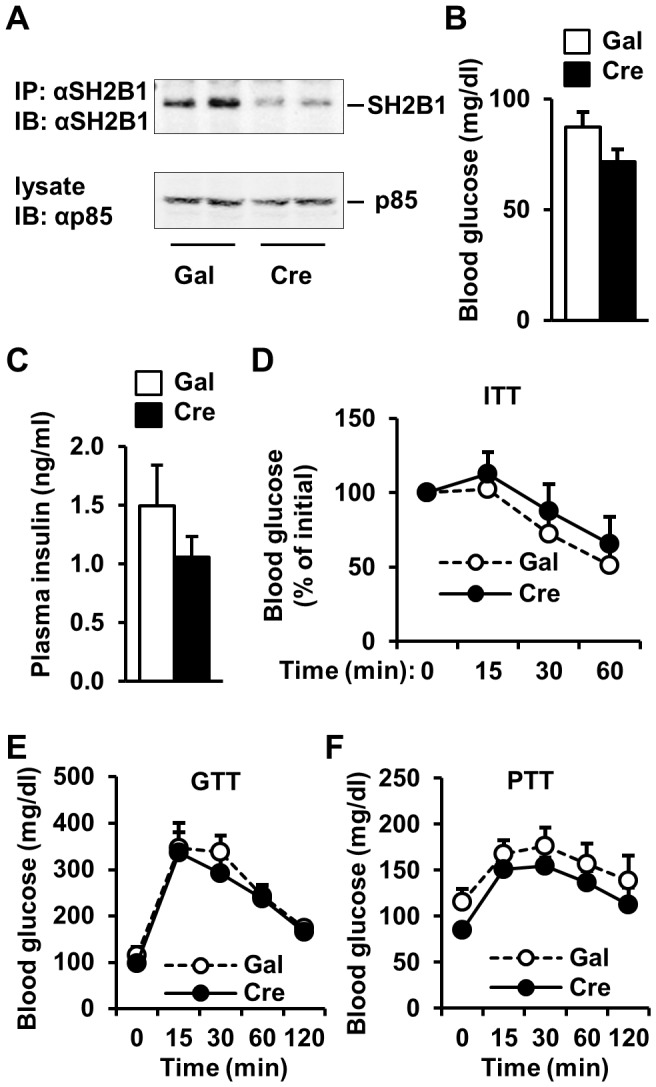

Embryonic onset deletion of hepatic SH2B1 may cause a developmental adaptation in HKO mice. To address this concern, we deleted SH2B1 in the livers of adult SH2B1f/f mice using Cre adenoviral infection. SH2B1f/f male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks, and infected with Cre or β-glactosidase (Gal) adenoviruses via tail vein injection. Cre but not Gal adenoviral infection markedly reduced SH2B1 protein levels in the liver (Fig. 4A). Fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were similar between Cre and Gal groups 10 days after infection (Figs. 4B, C). Insulin, glucose, and pyruvate tolerance tests were also indistinguishable between Cre and Gal adenovirus-infected mice (Figs. 4D-F). Taken together, these data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is dispensable for insulin regulation of glucose metabolism in mice under either normal or obese conditions.

Figure 4. Adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1 does not exacerbate HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

(A) Tissue extracts were prepared from male mice (7 weeks of age) 7 days after adenoviral infection. Tissue extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-SH2B1 antibody (upper panel). Tissue extracts were also immunoblotted with anti-p85 antibody (lower panel). (B-E) SH2B1f/f male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with β-gal (n = 7) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6) via tail vein injection. (B-C) Overnight fasting blood glucose (B) and plasma insulin levels (C) 10 days after adenoviral infection. (D) ITT (13 days after adenoviral infection). (E) GTT (16 days after adenoviral infection). (F) PTT (19 days after adenoviral infection).

Deletion of both SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver does not increase HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance

In HKO mice, SH2B2 (also called APS) may have a similar metabolic function and compensate for SH2B1 deficiency. To address this possibility, we deleted hepatic SH2B1 in SH2B2 knockout (SH2B2KO) mice. SH2B2KO mice were generated previously and reported to have slightly enhanced insulin sensitivity [12], [36]. SH2B2KO mice were crossed with SH2B1f/f to generate SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO double mutant mice. SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks, and infected with Cre or Gal adenoviruses via tail vein injection. Overnight fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were similar between Cre and Gal groups 10 days after infection (Fig. 5A). Responses to insulin (ITT), glucose (GTT), and pyruvate injection (PTT) were also indistinguishable between Cre and Gal adenovirus-infected mice (Figs. 5B, C, D). These data indicate that SH2B1 and SH2B2 in hepatocytes are not required for insulin suppression of hepatic glucose production and systemic glucose homeostasis even under HFD conditions.

Figure 5. Deletion of both SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver does not exacerbate HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with β-gal (n = 6) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6) via tail vein injection. (A) Overnight fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels 10 days after adenoviral infection. (B) ITT (13 days after adenoviral infection). (C) GTT (16 days after adenoviral infection). D-glucose: 1 g/kg body weight. (D) PTT (19 days after adenoviral infection). Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not protect against dietary liver injury

In cultured cells, SH2B1 promotes both the JAK/STAT and the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathways [14], [15], [18], [20]. These two pathways play a critical role in protecting against hepatocyte injury and promoting liver regeneration [37], [38]. To determine whether hepatic SH2B1 protects against liver injury, we fed HKO male mice (7 weeks of age) a methionine- and choline-deficient diet (MCD). MCD is commonly used to induce liver injury and NASH. Both MCD-fed HKO and SH2B1f/f mice similarly lost their body weights (Fig. 6A). MCD feeding reduced fasting blood glucose levels to a similar degree between SH2B1f/f and HKO mice (Fig. 6B). Responses to insulin (ITT) and glucose (GTT) injection were also indistinguishable between SH2B1f/f and HKO mice (Figs. 6C, D). Blood alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities are commonly used as biomarkers to estimate liver injury. MCD feeding similarly increased the activities of blood ALT and ALP in both SH2B1f/f and HKO mice (Figs. 6E, F). Blood bilirubin levels and liver TAG content were also similar between SH2B1f/f and HKO mice (Figs. 6G, H). These data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is not required for the maintenance of liver integrity and protection against liver injury.

Figure 6. Liver-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not augment MCD-induced liver injury.

Male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a MCD. (A) Growth curves. f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 7. (B) Overnight fasting blood glucose. f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (C) ITT (MCD for 7 weeks). f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (D) GTT (MCD for 6 weeks). f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (E) Plasma ALT activity. f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (F). Plasma ALP activity. f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (G) Plasma bilirubin levels (MCD for 8 weeks). f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. (H) Liver TAG levels (MCD for 8 weeks). f/f: n = 5; HKO: n = 5. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

Adult-onset, acute deletion of SH2B1 in the liver attenuates HFD-induced hepatic steatosis

To examine the role of hepatic SH2B1 in liver lipid metabolism, we measured liver weight and liver TAG levels. Both liver weight and TAG content were similar between albumin-Cre, SH2B1f/f, and HKO mice fed either a normal chow diet (Fig. 7A) or a HFD for 14 weeks (Fig. 7B).

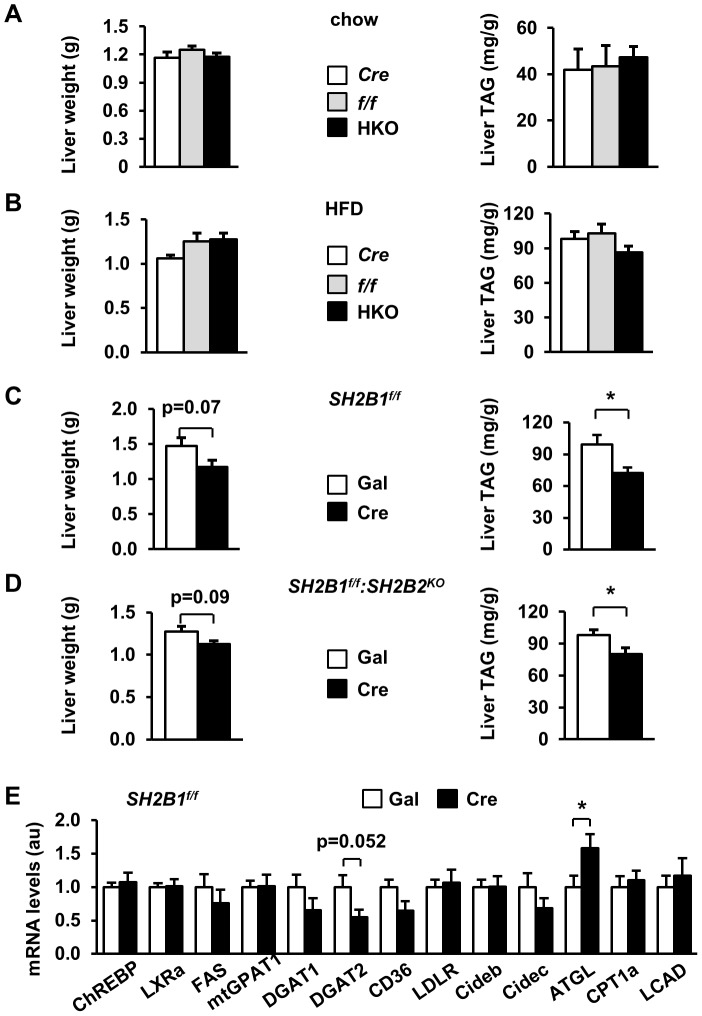

Figure 7. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 attenuates HFD-induced hepatic steatosis.

(A) Liver weight and liver TAG levels (normalized to liver weight) of overnight-fasted male mice (21 weeks of age). f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 7; HKO: n = 10. (B) Male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 14 weeks. Liver weight and TAG levels of overnight-fasted mice. f/f: n = 10; Cre: n = 7; HKO: n = 10. (C) SH2B1f/f male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with β-gal (n = 7) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6) via tail vein injection. Liver weight and TAG levels were measured in fasted mice 29 days after adenoviral infection. (D) SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with β-gal (n = 6) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6). Liver weight and TAG levels were measured in fasted mice 29 days after adenoviral infection. (E) Total liver mRNA was prepared from the mice described in (C) and used to measure mRNA levels of the indicated genes by qPCR and normalized to β-actin expression. The values were further normalized to the β-gal group. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

Embryonic deletion of hepatic SH2B1 in HKO mice may cause a developmental adaptation to compensate for SH2B1 deficiency. Therefore, we measured liver weight and TAG levels in mice with adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1. SH2B1f/f male mice were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and then infected with Cre adenoviruses to delete SH2B1 in the liver as described in Fig. 4. Liver weight was lower in the Cre group than in the Gal group (p = 0.07) 29 days after adenoviral infection; accordingly, liver TAG levels were significantly lower in mice with adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1 (Fig. 7C). In a separate mouse model, adult SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with Cre or Gal adenoviruses. Adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1 similarly attenuated HFD-induced hepatic steatosis in SH2B2 KO mice 29 days after infection (Fig. 7D). Together, these data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 promotes hepatic lipid accumulation in adult mice fed a HFD, which may contribute to obesity-associated NAFLD.

To gain insights into the potential mechanisms of SH2B1 action, we measured the expression of key genes that regulate lipid metabolism in the liver. The expression of most lipogenic genes (e.g. ChREBP, LXRa, FAS, mtGPAT1, and DGAT1) as well as the genes that regulate lipid uptake (e.g. CD36 and LDLR), lipid droplet activity (Cideb and Cidec), and fatty acid β oxidation (e.g CPT1a and LCAD) was similar between Cre and Gal adenovirus-infected SH2B1f/f mice (Fig. 7E). However, the expression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), an enzyme which synthesizes TAG, was lower in Cre adenovirus-infected SH2B1f/f mice (Fig. 7E). In contrast, the expression of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), a key lipolytic enzyme, was significantly higher in Cre adenovirus-infected SH2B1f/f mice (Fig. 7E). These data suggest that deletion of hepatic SH2B1 may decrease TAG synthesis and increase lipolysis, leading to lower hepatic lipid content in mice with adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1.

Deletion of both SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver attenuates VLDL secretion

High TAG levels promote VLDL secretion from hepatocytes [39]. To examine the role of hepatic SH2B1 in VLDL secretion, HKO, albumin-Cre, and SH2B1f/f male mice were fed either a chow diet or a HFD for 14 weeks. Mice were treated with Triton WR1339 to block VLDL clearance, and VLDL secretion was estimated by measuring blood TAG levels after Triton WR1339 treatment. VLDL secretion was similar between HKO, albumin-Cre, and SH2B1f/f male mice fed either a normal chow (Fig. 8A) or a HFD (Fig. 8B). Even though adult-onset deletion of liver SH2B1 attenuated HFD-induced hepatic steatosis in obese SH2B1f/f mice as described in Fig. 7C, it did not decrease VLDL secretion (Fig. 8C). Systemic deletion of SH2B2 also did not decrease VLDL secretion in SH2B2KO mice fed a HFD (Fig. 8D). To determine whether deletion of both SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver affect VLDL secretion, SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice were fed a HFD for 5 weeks and infected with Cre or Gal adenoviruses as described in Fig. 7D. Simultaneous deletion of both SH2B1 in the liver and SH2B2 in the whole body significantly reduced VLDL secretion (Fig. 8E). These data suggest that SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver may have a redundant function in promoting VLDL secretion; therefore, deletion of both, but not SH2B1 or SH2B2 alone, impairs VLDL secretion.

Figure 8. Deletion of both SH2B1 and SH2B2 in the liver suppresses VLDL secretion.

(A) VLDL secretion in the mice (20 weeks of age) described in Fig. 7A. (B) Male mice (7 weeks of age) were fed a HFD for 13 weeks as described in Fig. 7B, and VLDL secretion was measured. (C) SH2B1f/f male mice were fed a HFD and infected with β-gal (n = 7) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6) as described in Fig. 7C. VLDL secretion was measured 22 days after adenoviral infection. (D) VLDL secretion was measured in SH2B2 knockout and WT males (11 weeks of ages). SH2B2KO: n = 5; WT: n = 5. (E-F) SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO male mice were fed a HFD and infected with β-gal (n = 6) or Cre adenoviruses (n = 6) as described in Fig. 7D. (E) VLDL secretion was measured 22 days after adenoviral infection. (F) The expression of the indicated genes was measured by qPCR and normalized to β-actin expression. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P<0.05.

To gain insights into the potential mechanisms of SH2B1 regulation of VLDL secretion, we measured the expression of key genes which regulate lipid metabolism and VLDL secretion in the livers of Cre or Gal adenovirus-infected SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO mice. In agreement with Fig. 7E, the expression of ChREBP, LXRa, FAS, mtGPAT1, DGAT1, CD36, LDLR, Cideb, Cidec, CPT1a, LCAD, ApoB, ApoE, and MTP was similar between Cre and Gal groups; DGAT2 expression was lower, whereas ATGL expression was higher, in the Cre group (Fig. 8F). Surprisingly, the expression of ApoB, ApoE, and MTP, which promote VLDL secretion, was similar between Cre and Gal groups (Fig. 8F).

Discussion

SH2B1, a ubiquitously expressed adaptor protein, is a key metabolic regulator, and its metabolic function is conserved from insects to humans [25], [28], [33]. Impaired SH2B1 function is associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes in humans [30]–[34]. In this study, we have elucidated a new function of SH2B1 in the liver.

SH2B1 was highly expressed in the liver. It binds to both insulin receptors and IRS proteins, and enhances IRS protein-mediated activation of the PI 3-kinase pathway in cultured cells [18]–[20], [40], [41]. We hypothesized that hepatic SH2B1 increases the ability of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose production. Surprisingly, hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 did not cause hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, or glucose intolerance in HKO mice. Unlike TgKO mice which are prone to HFD-induced insulin resistance, HFD-fed HKO mice developed insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and pyruvate intolerance to a similar degree as albumin-Cre and SH2B1f/f mice fed a HFD. Adult-onset deletion of hepatic SH2B1 also did not exacerbate HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Furthermore, simultaneous deletion of both hepatic SH2B1 and whole body SH2B2 neither caused insulin resistance nor exacerbated HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. These data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is dispensable for insulin regulation of glucose metabolism in either normal or obese mice. Since deletion of SH2B1 in the entire peripheral tissues exacerbates HFD-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in TgKO mice [20], SH2B1 in other peripheral tissues (e.g. skeletal muscle and/or adipose tissue) is likely to promote insulin regulation of glucose metabolism.

SH2B1 directly enhances growth hormone signaling and promotes activation of both the JAK2/STAT and the PI 3-kinase pathways in cultured cells [11], [18], [42]. The JAK2/STAT and the PI 3-kinase pathways regulate liver injury and regeneration [37], [38]. Thus, we hypothesized that hepatic SH2B1 may protect against liver injury as well as mediate growth hormone stimulation of somatic growth. However, HKO mice had normal growth rates and body weight. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SH2B1 also did not exacerbate MCD-induced liver injury in HKO mice. These results indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is not required for liver homeostasis and somatic growth.

We also hypothesized that hepatic SH2B1 directly promotes lipogenesis in hepatocytes by enhancing insulin action. However, liver size and liver TAG levels were similar between HKO, albumin-Cre, and SH2B1f/f mice fed either a normal chow or a HFD. Unlike embryonic deletion of hepatic SH2B1 in HKO mice, adult-onset deletion of hepatic SH2B1 attenuated HFD-induced hepatic steatosis in both SH2B1f/f and SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO mice. It is likely that embryonic deletion of hepatic SH2B1 causes a developmental adaptation which compensates for SH2B1 deficiency in the livers of HKO mice. Adult-onset deletion of hepatic SH2B1 did not decrease the expression of most insulin-regulated lipogenic genes, but it decreased DGAT2 expression and increased ATGL expression. These observations raise the possibility that hepatic SH2B1 stimulates DGAT2-mediated TAG synthesis and inhibits ATGL-mediated lipolysis, thus increasing hepatic lipid content and/or VLDL secretion.

Interestingly, deletion of SH2B1 in the entire peripheral tissues augmented HFD-induced hepatic steatosis in TgKO mice. Hepatic steatosis in TgKO mice may be explained by SH2B1 regulation of crosstalk between different metabolic tissues. For instance, adipose SH2B1, which is present in HKO but not in TgKO mice, may regulate adipose lipolysis and/or endocrine function, thus indirectly regulating lipid metabolism in the liver. Unlike HKO mice, TgKO mice developed more severe insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia than WT control mice upon feeding a HFD. Hyperinsulinemia may counteract hepatic SH2B1-deficiency and stimulate lipogenesis and hepatic steatosis in TgKO mice.

Deletion of either SH2B1 in the liver or SH2B2 in whole body alone did not decrease VLDL secretion; however, simultaneous deletion of both significantly reduced VLDL secretion in SH2B1f/f:SH2B2KO mice. Therefore, hepatic SH2B1 and SH2B2 are likely to act redundantly to promote VLDL production and/or secretion. Lower liver TAG levels in the mutant mice are likely to contribute to reduced VLDL secretion. However, deletion of SH2B1 alone in SH2B1f/f mice decreased only hepatic TAG levels but not VLDL secretion, suggesting that hepatic SH2B1 and SH2B2 promote VLDL secretion by additional mechanisms. Insulin signaling is unlikely to mediate SH2B1/SH2B2-promotion of VLDL secretion, because insulin suppresses VLDL secretion. It will be interesting to determine whether JAK2 mediates SH2B1 and SH2B2 regulation of VLDL secretion in the future.

In summary, we report that liver-specific deletion of SH2B1 does not affect hepatic glucose production, systemic insulin sensitivity, and glucose intolerance. Adult onset, but not embryonic, deletion of hepatic SH2B1 attenuates HFD-induced hepatic steatosis. Deletion of both, but not hepatic SH2B1 or SH2B2 alone, impairs VLDL secretion. Our data indicate that hepatic SH2B1 is a novel regulator of TAG biosynthesis, lipolysis, and VLDL secretion.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Models

Animal experiments were conducted following the animal protocols approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) at the University of Michigan. TgKO mice were generated and verified previously [27]. Hepatocyte-specific SH2B1 knockout (HKO) mice were generated using the Cre/loxP system. SH2B1f/f mice have been generated and verified previously [35]. One loxP site was inserted into the intron between the second and third exons of SH2B1 and a second loxP site was inserted into the intron between the fifth and sixth exons. Exons 2–5 encode amino acids 1–436 of all four SH2B1 isoforms. HKO mice (genotype: SH2B1f/f;Cre+/−) were generated by crossing SH2B1f/f with albumin-Cre mice (C57BL/6 genetic background). Mice were housed on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle in the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of Michigan, and fed either a standard rodent chow diet (9% fat; Lab Diet, St. Louis, MO), HFD (60% fat, D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or MCD (A02082002B, New Brunswick, NJ) ad libitum with free access to water.

Animal experiments

Tail blood samples were collected. Plasma insulin levels were measured using a rat insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem Inc., Downers Grove, IL). Plasma ALT, ALP, and bilirubin levels were measured using an ALT reagent set, an ALP reagent set, and a total bilirubin reagent set (Pointe Scientific Inc., Canton, MI), respectively. Blood TAG levels were measured using a TAG assay kit (Pointe Scientific Inc., Canton, MI). Glucose tolerance tests (GTT), insulin tolerance tests (ITT), and pyruvate tolerance tests were conducted as previously described [2]. Mice were anesthetized with avertin (2.5 g tribromoethanol and 5 ml tert-amyl alcohol in 200 ml of water; 0.02 ml/g of body weight) and euthanized, and tissues were harvested and stored at −80°C.

H & E staining

Paraffin sections of liver and adipose tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and visualized using a BX51 microscope equipped with a DP70 Digital Camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

TAG concentrations

Liver samples were homogenized in 1% acetic acid. Cell lysates were extracted by chloroform:methanol (2∶1). The organic phase was transferred to a new tube and dried by evaporation. Lipid residues were dissolved in isopropanol and measured using a TAG assay kit (Pointe Scientific Inc., Canton, MI).

VLDL secretion assays

Mice were fasted for 5 h and then intravenously injected with Triton WR1339 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 600 mg/kg body weight. Blood samples were collected 0–3 h after injection and used to measure TAG concentrations.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Frozen tissue samples were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin). Tissue extracts were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Antibody dilution ratios for immunoblotting were: SH2B1 (Laboratory-generated): 1∶10,000; p80 (Laboratory-generated): 1∶10,000.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (qPCR)

qPCR was performed using absolute QPCR SYBR Green kits (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Mx3000P real-time PCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as described previously [2]. Primer sequences are: CPT-1a forward: 5′-CTGATGACGGCTATGGTGTTT-3′, reverse: 5′-GTGAGGCCAAACAAGGTGATA-3′; FAS forward: 5′-TTGACGGCTCACACACCTAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CGATCTTCCAGGCTCTTCAG-3′; ChREBP forward: 5′-CTGGGGACCTAAACAGGAGC-3′, reverse: 5′-GAAGCCACCCTATAGCTCCC-3′; LXRa forward: 5′-GAGTTCTCCAGAGCCATGAATG-3′, reverse: 5′-ATATGTGTGTTGCAGCCTCTCT-3′; mtGPAT1 forward: 5′-ACGCTGAGAGTGCCACATACT-3′, reverse: 5′-GAGAGATCGCTACAGCACCAC-3′; DGAT1 forward: 5′-CGTGGTATCCTGAATTGGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGCGCTTCTCAATCTGAAAT-3′; DGAT2 forward: 5′-ATCTTCTCTGTCACCTGGCT-3′, reverse: 5′-ACCTTTCTTGGGCGTGTTCC-3′; CD36 forward: 5′-GGAGTGGTGATGTTTGTTGCT-3′, reverse: 5′-GCACACACCACCATTTCTTCT-3′; LDLR forward: 5′-CAGAAGACCACAGAGGACGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-GGGAGGTCTGGAGAGAGTGTC-3′; Cideb forward: 5′-GACCCTTCCGTGTCTGTGAT-3′, reverse: 5′-GTAGCAGCAAGGTCTCCAGG-3′; Cidec forward: 5′-CCTATGACCTGCACTGCTACAAG-3′, reverse: 5′-CATGTAGCTGGAGGTGCCAAG-3′; ATGL forward: 5′-TTCACCATCCGCTTGTTGGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-AGATGGTCACCCAATTTCCTC-3′; ApoB forward: 5′-CCAGAGTGTGGAGCTGAATGT-3′, reverse: 5′-TTGCTTTTTAGGGAGCCTAGC-3′; ApoE forward: 5′-CTGAACCGCTTCTGGGATTAC-3′, reverse: 5′-TCCGTCATAGTGTCCTCCATC-3′; MTP forward: 5’-CTCCACAGTGCAGTTCTCACA-3′, reverse: 5′- AGAGACATATCCCCTGCCTGT-3′; LCAD forward: 5′-CACTCAGATATTGTCATGCCCT-3′, reverse: 5′-TCCATTGAGAATCCAATCACTC-3′; β-actin forward: 5′-AAATCGTGCGTGACATCAAA-3′, reverse: 5′-AAGGAAGGCTGGAAAAGAGC-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were determined by two-tailed Student's t tests. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Morris and Hong Shen and Ms Suqing Wang for their helpful discussions. Liang Sheng's current address: Department of Pharmacology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Nanjing Medical University, China.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK 065122, DK091591, and DK094014. This work utilized cores supported by the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (funded by NIH 5P60 DK20572), the University of Michigan's Cancer Center (funded by NIH 5 P30 CA46592), the University of Michigan Nathan Shock Center (funded by NIH P30AG013283), and the University of Michigan Gut Peptide Research Center (funded by NIH DK34933). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Postic C, Dentin R, Girard J (2004) Role of the liver in the control of carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis. Diabetes Metab 30: 398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sheng L, Zhou Y, Chen Z, Ren D, Cho KW, et al. (2012) NF-kappaB-inducing kinase (NIK) promotes hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in obesity by augmenting glucagon action. Nat Med 18: 943–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis JR, Mohanty SR (2010) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review and update. Dig Dis Sci 55: 560–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cole LK, Vance JE, Vance DE (2012) Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and lipoprotein metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821: 754–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiao C, Hsieh J, Adeli K, Lewis GF (2011) Gut-liver interaction in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301: E429–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larter CZ, Yeh MM (2008) Animal models of NASH: getting both pathology and metabolic context right. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23: 1635–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mendez-Sanchez N, Arrese M, Zamora-Valdes D, Uribe M (2007) Current concepts in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 27: 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheng L, Jiang B, Rui L (2013) Intracellular lipid content is a key intrinsic determinant for hepatocyte viability and metabolic and inflammatory states in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E1115–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI (2012) Diacylglycerol activation of protein kinase Cepsilon and hepatic insulin resistance. Cell Metab 15: 574–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maures TJ, Kurzer JH, Carter-Su C (2007) SH2B1 (SH2-B) and JAK2: a multifunctional adaptor protein and kinase made for each other. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rui L, Mathews LS, Hotta K, Gustafson TA, Carter-Su C (1997) Identification of SH2-Bbeta as a substrate of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 involved in growth hormone signaling. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6633–6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li M, Ren D, Iseki M, Takaki S, Rui L (2006) Differential role of SH2-B and APS in regulating energy and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 147: 2163–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Velazquez L, Cheng AM, Fleming HE, Furlonger C, Vesely S, et al. (2002) Cytokine signaling and hematopoietic homeostasis are disrupted in Lnk-deficient mice. J Exp Med 195: 1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Z, Zhou Y, Carter-Su C, Myers MG Jr, Rui L (2007) SH2B1 Enhances Leptin Signaling by Both Janus Kinase 2 Tyr813 Phosphorylation-Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol 21: 2270–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rui L, Carter-Su C (1999) Identification of SH2-bbeta as a potent cytoplasmic activator of the tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 7172–7177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Javadi M, Hofstatter E, Stickle N, Beattie BK, Jaster R, et al. (2012) The SH2B1 adaptor protein associates with a proximal region of the erythropoietin receptor. J Biol Chem 287: 26223–26234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rider L, Diakonova M (2011) Adapter protein SH2B1beta binds filamin A to regulate prolactin-dependent cytoskeletal reorganization and cell motility. Mol Endocrinol 25: 1231–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duan C, Li M, Rui L (2004) SH2-B promotes insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1)- and IRS2-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in response to leptin. J Biol Chem 279: 43684–43691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morris DL, Cho KW, Rui L (2010) Critical role of the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain of neuronal SH2B1 in the regulation of body weight and glucose homeostasis in mice. Endocrinology 151: 3643–3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morris DL, Cho KW, Zhou Y, Rui L (2009) SH2B1 enhances insulin sensitivity by both stimulating the insulin receptor and inhibiting tyrosine dephosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins. Diabetes 58: 2039–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kong M, Wang CS, Donoghue DJ (2002) Interaction of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 and the adapter protein SH2-B. A role in STAT5 activation. J Biol Chem 277: 15962–15970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rui L, Carter-Su C (1998) Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates the association of SH2-Bbeta with PDGF receptor and phosphorylation of SH2-Bbeta. J Biol Chem 273: 21239–21245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qian X, Riccio A, Zhang Y, Ginty DD (1998) Identification and characterization of novel substrates of Trk receptors in developing neurons. Neuron 21: 1017–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rui L, Herrington J, Carter-Su C (1999) SH2-B is required for nerve growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem 274: 10590–10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duan C, Yang H, White MF, Rui L (2004) Disruption of the SH2-B gene causes age-dependent insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7435–7443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ren D, Li M, Duan C, Rui L (2005) Identification of SH2-B as a key regulator of leptin sensitivity, energy balance, and body weight in mice. Cell Metabolism 2: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ren D, Zhou Y, Morris D, Li M, Li Z, et al. (2007) Neuronal SH2B1 is essential for controlling energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest 117: 397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Song W, Ren D, Li W, Jiang L, Cho KW, et al. (2010) SH2B regulation of growth, metabolism, and longevity in both insects and mammals. Cell Metab 11: 427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Werz C, Kohler K, Hafen E, Stocker H (2009) The Drosophila SH2B family adaptor Lnk acts in parallel to chico in the insulin signaling pathway. PLoS Genet 5: e1000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJ, Li S, Lindgren CM, et al. (2009) Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat Genet 41: 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet 41: 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachmann-Gagescu R, Mefford HC, Cowan C, Glew GM, Hing AV, et al. (2010) Recurrent 200-kb deletions of 16p11.2 that include the SH2B1 gene are associated with developmental delay and obesity. Genet Med 12: 641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doche ME, Bochukova EG, Su HW, Pearce LR, Keogh JM, et al. (2012) Human SH2B1 mutations are associated with maladaptive behaviors and obesity. J Clin Invest 122: 4732–4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Renstrom F, Payne F, Nordstrom A, Brito EC, Rolandsson O, et al. (2009) Replication and extension of genome-wide association study results for obesity in 4923 adults from northern Sweden. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1489–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Morris DL, Jiang L, Liu Y, Rui L (2013) SH2B1 in beta cells regulates glucose metabolism by promoting beta cell survival and islet expansion. Diabetes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Minami A, Iseki M, Kishi K, Wang M, Ogura M, et al. (2003) Increased insulin sensitivity and hypoinsulinemia in APS knockout mice. Diabetes 52: 2657–2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kong X, Horiguchi N, Mori M, Gao B (2012) Cytokines and STATs in Liver Fibrosis. Front Physiol 3: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matsuda S, Kobayashi M, Kitagishi Y (2013) Roles for PI3K/AKT/PTEN Pathway in Cell Signaling of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. ISRN Endocrinol 2013: 472432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu M, Chung S, Shelness GS, Parks JS (2012) Hepatic ABCA1 and VLDL triglyceride production. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821: 770–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang M, Deng Y, Tandon R, Bai C, Riedel H (2008) Essential role of PSM/SH2-B variants in insulin receptor catalytic activation and the resulting cellular responses. J Cell Biochem 103: 162–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ahmed Z, Pillay TS (2003) Adapter protein with a pleckstrin homology (PH) and an Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (APS) and SH2-B enhance insulin-receptor autophosphorylation, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signalling. Biochem J 371: 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Herrington J, Diakonova M, Rui L, Gunter DR, Carter-Su C (2000) SH2-B is required for growth hormone-induced actin reorganization. J Biol Chem 275: 13126–13133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]