Abstract

Objective

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study is designed to identify environmental exposures triggering islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes (T1D) in genetically high-risk children. We describe the first 100 participants diagnosed with T1D, hypothesizing that 1) they are diagnosed at an early stage of disease, 2) a high proportion are diagnosed by an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and 3) risk for early T1D is related to country, population, HLA-genotypes and immunological markers.

Methods

Autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), insulinoma-associated protein 2 (IA-2) and insulin (IAA) were analysed from 3 months of age in children with genetic risk. Symptoms and laboratory values at diagnosis were obtained and reviewed for ADA criteria.

Results

The first 100 children to develop T1D, 33 first-degree relatives (FDRs), with a median age 2.3 years (0.69–6.27), were diagnosed between 9/2005 and 11/2011. Although young, 36% had no symptoms and ketoacidosis was rare (8%). An OGTT diagnosed 9/30 (30%) children above 3 years of age but only 4/70 (5.7%) below the age of 3 years. FDRs had higher cumulative incidence than children from the general population (p<0.0001). Appearance of all three autoantibodies at seroconversion was associated with the most rapid development of T1D (HR=4.52, p<0.014), followed by the combination of GADA and IAA (HR=2.82, p=0.0001).

Conclusions

Close follow-up of children with genetic risk enables early detection of T1D. Risk factors for rapid development of diabetes in this young population were FDR status and initial positivity for GADA, IA-2, and IAA or a combination of GADA and IAA.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, diagnosis, follow-up studies, autoantibodies, TEDDY study

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes is one of the most common autoimmune diseases in children, with about 70,000 cases diagnosed during childhood world-wide each year (1). However, the environmental triggers associated with islet autoimmunity and the subsequent development of type 1 diabetes remain poorly understood. To enhance our understanding of the environmental factors associated with type 1 diabetes, The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study was designed to prospectively follow children identified at birth with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes indicating increased risk for type 1 diabetes (2). The TEDDY study was initiated in 2004 and now follows 6,481 children with a median age of 58 months. Data analyses of the children in TEDDY who have developed type 1 diabetes have demonstrated marked reductions in the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis when compared to children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the general population (3). In addition, a large number of TEDDY participants developing type 1 diabetes have been asymptomatic, with diagnosis being made purely on the basis of an OGTT. Participants diagnosed at an early stage of the disease likely have a greater residual β-cell capacity, which may lead to better initial glycemic control and reduced risk of long term complications (4, 5). Based on these initial observations, the specific aim of this study was to describe the first 100 TEDDY participants diagnosed with type 1 diabetes according to their genetic background, immunological markers, and clinical presentation at the diagnosis of the disease. We hypothesized that 1) participants followed in TEDDY are diagnosed at an early stage of disease with a low frequency of symptoms and near normal HbA1c; 2) a high proportion of the participants over three years of age are diagnosed through an OGTT, and 3) different countries and populations within the TEDDY study as well as immunological markers and HLA-genotypes are important for type 1 diabetes risk in this young population.

Research Design and Methods

Participants

TEDDY is a multi-center observational study designed to identify the environmental exposures that may promote or protect from autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes (2). The clinical sites in the study are located in Sweden, Finland, Germany, Colorado, Washington, and Florida/Georgia. The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, approved by local Institutional Review Boards, and is monitored by an External Advisory Board formed by the National Institutes of Health. The participants were initially identified at birth via genetic screening for HLA genotypes known to confer an increased risk for type 1 diabetes (2). Those enrolled are being followed prospectively from birth to 15 years. Study visits beginning at 3 months of age continue every 3 months until 4 years and then every 6 months until the age of 15 years. Children who are positive for islet autoantibodies continue to receive follow up every 3 months regardless of age. The visits include clinical measurements, the collection of blood and other biological samples, and the collection of data to ascertain environmental exposures (2). A portion of the blood samples are analyzed for autoantibodies to glutamate decarboxylase (GADA), insulinoma-associated protein 2 (IA-2A) and insulin (IAA). In autoantibody positive participants older than 3 years of age, oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) are performed every 6 months. Parents are carefully informed about diabetes risk and provided with updated antibody results after each study visit.

Genetic analyses

The participants at all clinical sites were screened at birth for HLA HLA-DQA1, DQB1 and DRB1 genes as previously described (6). Confirmatory testing was performed by the TEDDY HLA Reference Laboratory (7). Nine high-risk haplo-genotypes were identified and participants with these genotypes were eligible for the follow-up phase of the study (7).

Autoantibodies

GADA, IA-2A and IAA were measured in two laboratories by radiobinding assays (8, 9). For sites in the United States (US), all serum samples were assayed at the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes at the University of Colorado Denver. In Europe, all sera were assayed at the University of Bristol, United Kingdom. Both laboratories have previously shown high assay sensitivity and specificity as well as concordance (10). All positive islet autoantibodies results and 5% of negative samples were re-tested in the other reference laboratory and deemed confirmed if concordant.

Definition of persistent autoimmunity

Persistent islet autoimmunity was defined as confirmed positive GADA, IA-2A, or IAA on at least two consecutive study visits. All positive islet autoantibodies and 5% of negative islet autoantibodies were confirmed in both central autoantibody laboratories, one located in the US and one in Europe.

Collection of data related to the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes

At the time of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, data were collected using a standardized case report form requiring documentation to fulfil American Diabetes Association criteria for diagnosis (11). Data on symptoms, height and weight at diagnosis, laboratory values such as pH, bicarbonate, and presence of ketones in urine and blood ketones are collected. Since the clinical care of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients differs between the TEDDY sites, not all participants had samples collected for laboratory evaluation of DKA. Therefore, a free text box for the physician’s description of the child’s clinical status of the child was added to the diagnosis of diabetes case report form.

Definition of DKA

DKA was defined as an arterial/capillary pH less than 7.30 or a standardized bicarbonate less than 15 mmol/L. Severe DKA was defined as pH less than 7.10 or standardized bicarbonate less than 5 mmol/L. If the pH or standardized bicarbonate were not taken at diagnosis, DKA was excluded on the basis of betahydroxybutyrate less than 1.5 mmol/L, negative urine ketones, lack of symptoms, or physician diagnosis.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System Software (Version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 tests. Continuous variables were tested using the t test for differences in means or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for differences in medians. Medians and minimum/maximum values are presented as median (min, max). Autoantibody seroconversion was defined as first confirmed positive sample for a specific autoantibody. Kaplan-Meier life tables were used to determine the time to development of type 1 diabetes by first confirmed autoantibody combination and compared using the log-rank χ2 statistic and to determine the cumulative incidence by clinical center. Stratified Cox proportional hazard models (stratified for country of residence) were used to estimate the hazards ratio for risk of type 1 diabetes development by first confirmed autoantibodies (reference group = IAA only). Multivariable analyses were adjusted for gender, relation to type 1 diabetes proband and HLA genotype. Efron’s method for tied survival times were employed in the Cox analysis.

Results

The screening in TEDDY started on September 1, 2004 and the first TEDDY child was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in September 2005. By November 30, 2011, a total of 100 TEDDY participants had been diagnosed, 45 females and 55 males. The median age at diagnosis was 2.3 years (min 0.69–max 6.27). Thirty-three percent (33/100) had a first degree relative (FDR) with type 1 diabetes (father (n=20), mother (n=6), sibling (n=9))(Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the first 100 TEDDY children diagnosed with T1D.

| Characteristic | n or median (min-max) |

|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 45 |

| FDR (yes) | 33 |

| Family member with T1D | |

| Mother only | 4 |

| Father only | 18 |

| Sibling only | 9 |

| Mother and father | 2 |

| Mothers diabetes status | |

| Gestational | 4 |

| Type 1 | 6 |

| No diabetes | 86 |

| Missing | 4 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 2.3 (min 0.69, max 6.27) |

| Number and median age at diagnosis (min-max) by site | |

| Colorado | n=14, age 1.76 (1.1–3.7) |

| Georgia/Florida | n=4, age 2.45 (1.2–4.3) |

| Washington | n=7, age 2.77 (0.87–4.9) |

| Finland | n=35, age 2.05 (0.69–5.1) |

| Germany | n=13, age 1.96 (1.0–3.2) |

| Sweden | n=27, age 2.98 (0.9–6.3) |

Diagnosis per site

Of the first 100 children to develop type 1 diabetes, Finland had the highest number diagnosed (n=35) and Florida/Georgia had the lowest (n=4) (Table 1). The cumulative incidence did not differ significantly between Finland, Sweden, Germany, and the US when analyzing children recruited from the general population and FDRs separately (Fig 1 panel A and B). However, FDRs had a significantly higher cumulative incidence compared to children from the general population (p<0.0001) (Fig a panel C).

Figure 1.

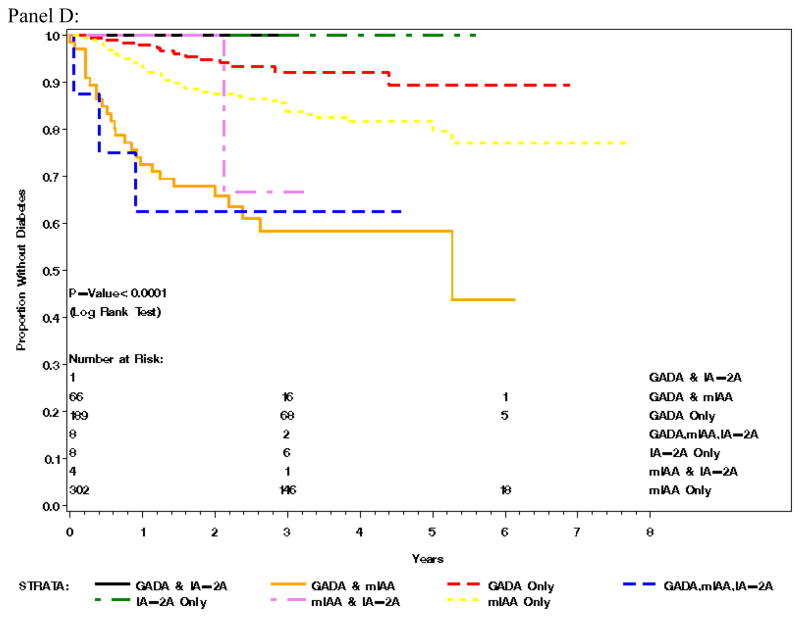

Panel A) Cumulative incidence of T1D in the general population by country, Panel B) Cumulative incidence of T1D in the first degree relatives by country, Panel C) Cumulative incidence of T1D by FDR status and Panel D) Survival analysis of first autoantibody measured and proportion of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes over time

Clinical symptoms and signs at diagnosis of diabetes

In total, 36 of 100 children were asymptomatic at diagnosis. When symptomatic, the most common symptoms were polydipsia (53 %) and polyuria (51%) (Table 2a). The majority of children (87/100) were diagnosed by a random, postprandial, or fasting glucose, while 13/100 children were diagnosed by a scheduled OGTT (Table 2b). Amongst those children diagnosed before 3 years of age (n=70), 94% were diagnosed by random (n=49), postprandial (n=9) or fasting (n=8) glucose, while only four (5.7 %) were diagnosed on OGTT. In contrast, 9/30 (30 %) of children above 3 years of age were diagnosed on OGTT. A total of 8/100 children were found to have DKA at diagnosis of disease (5/100 mild DKA and 3/100 severe DKA [pH<7.1]) (Table 2b).

Table 2.

a and b. Symptoms and lab data at onset of T1D.

| Symptoms | N or Median (min-max) |

|---|---|

| Was child symptomatic (yes) | 64 |

| Polydipsia* (yes) | 53 |

| Polyphagia* (yes) | 4 |

| Polyuria* (yes) | 51 |

| Was child hospitalized (yes) | 82 |

| Was child treated in emergency room (yes) | 6 |

| Weight at diagnosis (kg) | 13 (6.5–27) |

| Height at diagnosis (cm) | 90 (70–126) |

| Weight loss reported at diagnosis (kg) | 0.5 (0.03–4.4) |

| Laboratory Values | n or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Diagnostic Test: | |

| Fasting glucose | 12 |

| OGTT - 2hr | 13 |

| Postprandial glucose | 14 |

| Random glucose | 61 |

|

| |

| Average pH (n=80) | 7.4 (0.1) |

|

| |

| >=7.1 and <7.3 | 5 |

|

| |

| <7.1 | 3 |

|

| |

| Average Glucose (mmol/l) (n=98) | 19.6 (9.7) |

|

| |

| HbA1c (%, mmol/mol) at diagnosis: | |

| All (n=98) | 7.4 (1.9), 57 |

| Colorado | 7.1 (1.4), 54 |

| Georgia/Fl | 7.4 (1.3), 57 |

| Washington | 8.7 (2.3), 72 |

| Finland | 7.6 (1.7), 60 |

| Germany | 8.4 (2.3), 68 |

| Sweden | 6.4 (1.7), 46 |

|

| |

| HbA1c at Diagnosis by Cutpoints (n=98): | |

| >=6.5 | 15 |

| >=5.7 and <6.5 | 23 |

| <5.7 | 60 |

|

| |

| Urine ketones at diagnosis (n=80) | |

| Large | 9 |

| Moderate | 11 |

| Small | 9 |

| Trace | 5 |

| Negative | 46 |

|

| |

| Blood ketones at diagnosis (mmol/L) | 0.98 (2.2) |

Missing=13

Autoantibodies before onset of type 1 diabetes

All but six of the first 100 children had developed confirmed GADA, IA-2A and/or IAA before diagnosis of diabetes. The first autoantibody to appear at seroconversion was most often IAA, present as the first autoantibody in 81/100 children either alone (49/100), in combination with GADA (28/100), IA-2A (1/100) or both GADA and IA-2A (3/100). In total, 44/100 children developed GADA as the first positive autoantibody. Only 13/100 had GADA as the single first autoantibody, while 31/100 had GADA in combination with IAA (28/100) or both IAA and IA-2 (3/100). None of the children developed IA-2A as the first antibody without positivity for IAA (Figure 2a). Of the initial 100 children to develop diabetes, 94/100 had confirmed positive autoantibodies (Fig 2b) and 83/100 children had persistent confirmed autoantibodies (i.e. more than one confirmed autoantibody positive sample), prior to diagnosis (Fig 2c).

Figure 2.

a) The first positive autoantibody (n) measured in the TEDDY study in the 100 children that later developed T1D; b) Confirmed autoantibodies at diagnosis of T1D; c) Persistent confirmed autoantibodies at diagnosis of T1D (17 subjects were not persistent). 6/100 subjects developing T1D did not have positive autoantibodies before diagnosis.

In six children, no sample with positive islet autoantibodies was obtained before the diagnosis of diabetes. Of those, two children, both FDR’s and aged 3.0 and 4.2 years at diagnosis, dropped out of TEDDY and no islet autoantibody information could be obtained as part of the study before the diagnosis. One of them had islet autoantibodies measured at the hospital (outside of TEDDY protocol) at the time of diagnosis and was found to be positive for GADA, IA-2A and IAA. The other child did not have any autoantibody measurement performed. Three of the four children followed in TEDDY had tested positive for an autoantibody once but the second laboratory did not confirm this. The mean age at diagnosis was 1.6 years (range 0.7–3.4). Three of the four were from the general population and two of the four had high risk HLA-genotypes (DR4-DQA1*030X-DQB1*0302/DR3-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201), while the other two had DR4/4 and DR 4/9 respectively. The last autoantibody samples were drawn 3 months before diagnosis in 2 children, and respectively 8 months and 10 months before diagnosis in the remaining two children.

Survival analysis of the first autoantibodies measured and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes over time was adjusted for sex, relation to proband status, HLA-genotype, and country of origin (Figure 1 panel D). The analysis demonstrated that the appearance of all three autoantibodies (GADA, IA-2A and IAA) compared to IAA only as the first confirmed autoantibody was associated with the most rapid development of type 1 diabetes (HR 4.52 (95 % CI 1.35–15.11; p=0.014), closely followed by the combination of GADA and IAA (HR 2.82 (1.69–4.71; p<0.0001). In contrast children with initial positivity for GADA as a single autoantibody had the slowest course to diabetes amongst this very young cohort with type 1 diabetes (HR 0.54 (0.29–1.00; p=0.05). The combination of IA-2 and IAA did not significantly differ from IAA as a single autoantibody (Figure 1 panel D).

Genetic background

The majority of the children (98%) had a genotype containing the haplotypes DR4- DQA1*030X-DQB1*0302 (DR4), DR3-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201 (DR3), or both (DR3/4). The high risk DR3/4 genotype represented 58%.

Discussion

The TEDDY study provides a unique opportunity to longitudinally follow the progression to autoantibody seroconversion and type 1 diabetes in a large group of children with known HLA risk for the disease. Having reached the unfortunate “milestone” of 100 diagnosed children we have analyzed this group of predominantly young children who have developed type 1 diabetes and have questioned if the natural course from seroconversion to diagnosis of type 1 diabetes may be altered by virtue of participation in a highly intensive longitudinal study.

The observation of multiple autoantibodies at the initial presentation of autoimmunity likely reflects the rapid natural history of type 1 diabetes in very young children at high genetic risk for developing disease. Since children presenting with all three of GADA, IA-2A and IAA and the combination of GADA and IAA may be of increased risk of more aggressive autoimmune beta-cell destruction than children with GADA or IAA as single first autoantibodies, it may be important for future prevention and intervention trials in young children with high-risk HLA-genotypes to stratify treatment groups based on these autoantibody combinations.

In this population of children with genetically increased risk for type 1 diabetes, we also found that FDRs had a higher cumulative incidence than children from the general population. Children followed in Germany had the highest cumulative incidence at early age of diagnosis when analyzing all children followed together (data not shown). This was explained by the high percentage of FDRs followed at the German site, given that 10/13 children diagnosed in Germany were FDRs. The fact that no significant country differences were seen in early incidence when FDRs and children from general population were analyzed separately in our analyses may be explained by the selection of the genetically at risk children within the TEDDY study. In this context it is interesting to note that the TEDDY protocol allows FDRs with less HLA genetic risk to be followed, while all children followed from the general population have high-risk genotypes (7). However, in this young population we could confirm a high frequency of the high-risk HLA-genotype DR4-DQA1*030X-DQB1*0302/DR3-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201 also in the FDRs diagnosed (51 %), which is consistent with other studies in children diagnosed at a young age (12, 13).

Our data demonstrates that more than 1/3 of TEDDY subjects are asymptomatic at diagnosis, despite a median diagnosis age of 2.3 years. In contrast, 99 % of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the community (i.e. outside of a research study) before age 6 years have been reported to be symptomatic at diagnosis (14). These observations provide further support for the concept that longitudinal monitoring including HLA screening, autoantibody measurements, and frequent reinforcement of the signs and symptoms of type 1 diabetes may be highly effective (though not necessarily cost effective) in improving outcomes for young children with type 1 diabetes. This study also confirmed that DKA rates are very low in TEDDY subjects who developed type 1 diabetes when compared to rates in the general population (15–19). Other studies with close follow up of children with risk have shown a similar trend of early diagnosis with a low rate of DKA (20, 21) and symptoms (20, 22, 23), although the latter is in an older population.

The high number of asymptomatic children indicates that dissemination of risk information alone may not be enough to identify young children at an early stage of disease. Frequent follow up with HbA1c, blood or plasma glucose, and OGTTs may be of great importance in early identification of type 1 diabetes development. That said, only 13/100 children were diagnosed based on an OGTT. The vast majority was diagnosed on the basis of random, postprandial, or fasting glucoses. Thus, close follow up with plasma glucose sampling and HbA1c appear to contribute to the early diagnosis of these children. As the cohort ages, however, it appears that OGTT may become a far more important diagnostic tool in the monitoring of at risk children as 30 % of children diagnosed above the age of three met criteria on the basis of an OGTT.

In conclusion the first 100 children diagnosed within the TEDDY study, where children with increased risk for type 1 diabetes are closely followed, have a high rate of asymptomatic development of type 1 diabetes. Combinations of autoantibodies to islet autoantigens may be used to further stratify risk for progression to development of type 1 diabetes in young children with high risk HLA-genotypes.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the clinical staff and the Clinical Implementation Committee for their assistance in collecting thorough diabetes data: Claire Crouch, Gertie Hansson, Michelle Hoffman, Maija Sjoberg, Leigh Steed, Riitta Veijola, Katharina Warncke.

The TEDDY Study Group (See appendix)

Funded by DK 63829, 63861, 63821, 63865, 63863, 63836, 63790 and UC4DK095300 and Contract No. HHSN267200700014C from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Appendix

The Teddy Study Group

Colorado Clinical Center

Marian Rewers, M.D., Ph.D., PI1,4,6,10,11, Katherine Barriga12, Kimberly Bautista12, Judith Baxter9,12,15, George Eisenbarth, M.D., Ph.D., Nicole Frank2, Patricia Gesualdo2,6,12,14,15, Michelle Hoffman12,13,14, Lisa Ide, Rachel Karban12, Edwin Liu, M.D.13, Jill Norris, Ph.D.2,3,12, Kathleen Waugh7,12,15 Adela Samper-Imaz, Andrea Steck, M.D.3, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes.

Georgia/Florida Clinical Center

Jin-Xiong She, Ph.D.,PI1,3,4,11,†, Desmond Schatz, M.D.*4,5,7,8, Diane Hopkins12, Leigh Steed12,13,14,15, Jamie Thomas*6,12, Katherine Silvis2, Michael Haller, M.D.*14, Meena Shankar*2, Melissa Gardiner, Richard McIndoe, Ph.D., Haitao Liu, M.D.†, John Nechtman†, Ashok Sharma, Joshua Williams, Gabriela Foghis, Stephen W. Anderson, M.D.^ Medical College of Georgia, Georgia Regents University, *University of Florida, †Jinfiniti Biosciences LLC, Augusta, GA, ^Pediatric Endocrine Associates, Atlanta, GA.

Germany Clinical Center

Anette G. Ziegler M.D.,PI1,3,4,11, Andreas Beyerlein Ph.D.2, Ezio Bonifacio Ph.D.*5, Lydia Henneberger2,12, Michael Hummel M.D.13, Sandra Hummel Ph.D.2, Kristina Foterek¥2, Mathilde Kersting Ph.D.¥2, Annette Knopff7, Sibylle Koletzko, M.D.¶13, Stephanie Krause, Claudia Peplow12, Maren Pflüger Ph.D.6, Roswith Roth Ph.D.9, Julia Schenkel2,12, Joanna Stock9,12, Elisabeth Strauss12, Katharina Warncke M.D.14, Christiane Winkler Ph.D.2,12,15, Forschergruppe Diabetes e.V. at Helmholtz Zentrum München, *Center for Regenerative Therapies, TU Dresden, ¶Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital,Department of Gastroenterology, Ludwig Maximillians University Munich, ¥Research Institute for Child Nutrition, Dortmund.

Finland Clinical Center

Olli G. Simell, M.D., Ph.D.,PI¥^1,4,11,13, Heikki Hyöty, M.D., Ph.D.*±6, Jorma Ilonen, M.D., Ph.D.¥ ¶3, Mikael Knip, M.D., Ph.D.*±, Maria Lönnrot, M.D., Ph.D.*±6, Elina Mantymaki¥^, Juha Mykkänen, Ph.D.^¥ 3, Kirsti Nanto-Salonen, M.D., Ph.D.¥ ^12, Tiina Niininen±*12, Mia Nyblom*±, Anne Riikonen*±2, Minna Romo¥^, Barbara Simell¥^9,12,15, Tuula Simell, Ph.D.¥^9,12, Ville Simell^¥13, Maija Sjöberg¥^12,14, Aino Steniusμ¤12, Jorma Toppari, M.D., Ph.D., Eeva Varjonen¥^12, Riitta Veijola, M.D., Ph.D. μ¤14, Suvi M. Virtanen, M.D., Ph.D.*±§2. ¥University of Turku, *University of Tampere, μUniversity of Oulu, ^Turku University Hospital, ±Tampere University Hospital, ¤Oulu University Hospital, §National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland, ¶University of Kuopio.

Sweden Clinical Center

Åke Lernmark, Ph.D., PI1,3,4,5,6,8,10,11,15, Daniel Agardh, M.D., Ph.D.13, Carin Andrén-Aronsson2,13, Maria Ask, Jenny Bremer, Corrado Cilio Ph.D., M.D.5, Emilie Ericson-Hallström2, Lina Fransson, Thomas Gard, Joanna Gerardsson, Gertie Hansson12,14, Monica Hansen, Susanne Hyberg, Fredrik Johansen, Berglind Jonasdottir M.D., Ulla-Marie Karlsson, Helena Elding Larsson M.D., Ph.D. 6,14, Barbro Lernmark, Ph.D.9,12, Maria Markan, Theodosia Massadakis, Jessica Melin12, Maria Månsson-Martinez, Anita Nilsson, Kobra Rahmati, Monica Sedig Järvirova, Sara Sibthorpe, Birgitta Sjöberg, Ulrica Swartling, Ph.D. 9,12, Erika Trulsson, Carina Törn, Ph.D. 3,15, Anne Wallin, Åsa Wimar12, Sofie Åberg. Lund University.

Washington Clinical Center

William A. Hagopian, M.D., Ph.D., PI1,3,4, 5, 6,7,11,13, 14, Xiang Yan, M.D., Michael Killian6,7,12,13, Claire Cowen Crouch12,14,15, Kristen M. Hay2, Stephen Ayres, Carissa Adams, Brandi Bratrude, David Coughlin, Greer Fowler, Czarina Franco, Carla Hammar, Diana Heaney, Patrick Marcus, Arlene Meyer, Denise Mulenga, Elizabeth Scott, Jennifer Skidmore2, Joshua Stabbert, Viktoria Stepitova, Nancy Williams. Pacific Northwest Diabetes Research Institute.

Pennsylvania Satellite Center

Dorothy Becker, M.D., Margaret Franciscus12, MaryEllen Dalmagro-Elias2, Ashi Daftary, M.D. Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC.

Data Coordinating Center

Jeffrey P. Krischer, Ph.D., PI1,4,5,10,11, Michael Abbondondolo, Sarah Austin, Rasheedah Brown12,15, Brant Burkhardt, Ph.D.5,6, Martha Butterworth2, David Cuthbertson, Christopher Eberhard, Steven Fiske9, Veena Gowda, David Hadley, Ph.D.3,13, Hye-Seung Lee, Ph.D.3,6,13,15, Shu Liu, Kristian Lynch, Ph.D. 6,9, Jamie Malloy, Cristina McCarthy12,15, Wendy McLeod2,5,6,13,15, Laura Smith, Ph.D.9,12, Susan Smith12,15, Roy Tamura, Ph.D.2, Ulla Uusitalo, Ph.D.2,15, Kendra Vehik, Ph.D. 4,5,9,14,15, Earnest Washington, Jimin Yang, Ph.D., R.D.2,15. University of South Florida.

Project scientist

Beena Akolkar, Ph.D.1,3,4,5, 6,7,10,11, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Other contributors

Kasia Bourcier, Ph.D.5, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Thomas Briese, Ph.D.6,15, Columbia University, Suzanne Bennett Johnson, Ph.D.9,12, Florida State University, Steve Oberste, Ph.D.6, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Eric Triplett, Ph.D. 6, University of Florida.

Autoantibody Reference Laboratories

Liping Yu, M.D.^ 5, Dongmei Miao, M.D.^, Polly Bingley, M.D., FRCP*5, Alistair Williams*, Kyla Chandler*, Saba Rokni*, Anna Long Ph.D.*, Joanna Boldison*, Jacob Butterly*, Jessica Broadhurst*, Gabriella Carreno*, Rachel Curnock*, Peter Easton*, Ivey Geoghan*, Julia Goode*, James Pearson*, Charles Reed*, Sophie Ridewood*, Rebecca Wyatt*. ^Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, University of Colorado Denver, *School of Clinical Sciences, University of Bristol UK.

Cortisol Laboratory

Elisabeth Aardal Eriksson, M.D., Ph.D., Ewa Lönn Karlsson. Department of Clinical Chemistry, Linköping University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden.

Dietary Biomarkers Laboratory

Iris Erlund, Ph.D.2, Irma Salminen, Jouko Sundvall, Jaana Leiviskä, Mari Lehtonen, Ph.D. National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland.

HbA1c Laboratory

Randie R. Little, Ph.D., Alethea L. Tennill. Diabetes Diagnostic Laboratory, Dept. of Pathology, University of Missouri School of Medicine.

HLA Reference Laboratory

Henry Erlich, Ph.D.3, Teodorica Bugawan, Maria Alejandrino. Department of Human Genetics, Roche Molecular Systems.

Metabolomics Laboratory

Oliver Fiehn, Ph.D., Bill Wikoff, Ph.D., Tobias Kind, Ph.D., Mine Palazoglu, Joyce Wong, Gert Wohlgemuth. UC Davis Metabolomics Center.

Microbiome and Viral Metagenomics Laboratory

Joseph F. Petrosino, Ph.D.6 Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research, Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine.

OGTT Laboratory

Santica M. Marcovina, Ph.D., Sc.D. Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories, University of Washington.

Repository

Heather Higgins, Sandra Ke. NIDDK Biosample Repository at Fisher BioServices.

RNA Laboratory and Gene Expression Laboratory

Jin-Xiong She, Ph.D.,PI1,3,4,11, Richard McIndoe, Ph.D., Haitao Liu, M.D., John Nechtman, Yansheng Zhao, Na Jiang, M.D. Jinfiniti Biosciences, LLC.

SNP Laboratory

Stephen S. Rich, Ph.D.3, Wei-Min Chen, Ph.D.3, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu, Ph.D.3, Emily Farber, Rebecca Roche Pickin, Ph.D., Jordan Davis, Dan Gallo. Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia.

Committees

1Ancillary Studies, 2Diet, 3Genetics, 4Human Subjects/Publicity/Publications, 5Immune Markers, 6Infectious Agents, 7Laboratory Implementation, 8Maternal Studies, 9Psychosocial, 10Quality Assurance, 11Steering, 12Study Coordinators, 13Celiac Disease, 14Clinical Implementation, 15Quality Assurance Subcommittee on Data Quality

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to report regarding this study.

Author Contributions: H.E.L. researched data and wrote manuscript, M.J.H researched data and wrote manuscript, P.G. researched data and wrote manuscript, K.V. researched data, reviewed/edited manuscript, B.A., W.H., J.K., Å.L, M.R, O.S, J-S. X., A.Z. designed study, researched data and reviewed/edited manuscript.

References

- 1.IDF. Diabetes Atlas. 2006:2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1150:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1447.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elding Larsson H, Vehik K, Bell R, Dabelea D, Dolan L, Pihoker C, et al. Reduced prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in young children participating in longitudinal follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2347–52. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludvigsson J. Immune intervention at diagnosis--should we treat children to preserve beta-cell function? Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8 (Suppl 6):34–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowden SA, Duck MM, Hoffman RP. Young children (<5 yr) and adolescents (>12 yr) with type 1 diabetes mellitus have low rate of partial remission: diabetic ketoacidosis is an important risk factor. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiviniemi M, Hermann R, Nurmi J, Ziegler AG, Knip M, Simell O, et al. A high-throughput population screening system for the estimation of genetic risk for type 1 diabetes: an application for the TEDDY (the Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young) study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:460–72. doi: 10.1089/dia.2007.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagopian WA, Erlich H, Lernmark A, Rewers M, Ziegler AG, Simell O, et al. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY): genetic criteria and international diabetes risk screening of 421 000 infants. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:733–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonifacio E, Yu L, Williams AK, Eisenbarth GS, Bingley PJ, Marcovina SM, et al. Harmonization of glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet antigen-2 autoantibody assays for national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases consortia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3360–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babaya N, Yu L, Miao D, Wang J, Rewers M, Nakayama M, et al. Comparison of insulin autoantibody: polyethylene glycol and micro-IAA 1-day and 7-day assays. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:665–70. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torn C, Mueller PW, Schlosser M, Bonifacio E, Bingley PJ. Diabetes Antibody Standardization Program: evaluation of assays for autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet antigen-2. Diabetologia. 2008;51:846–52. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0967-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (Suppl 1):S4–10. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komulainen J, Kulmala P, Savola K, Lounamaa R, Ilonen J, Reijonen H, et al. Clinical, autoimmune, and genetic characteristics of very young children with type 1 diabetes. Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1950–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson C, Larsson K, Vaziri-Sani F, Lynch K, Carlsson A, Cedervall E, et al. The three ZNT8 autoantibody variants together improve the diagnostic sensitivity of childhood and adolescent type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:394–405. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2010.540604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn M, Fleischman A, Rosner B, Nigrin DJ, Wolfsdorf JI. Characteristics at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children younger than 6 years. The Journal of pediatrics. 2006;148:366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rewers A, Klingensmith G, Davis C, Petitti DB, Pihoker C, Rodriguez B, et al. Presence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in youth: the Search for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1258–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schober E, Rami B, Waldhoer T. Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis in Austrian children in 1989–2008: a population-based analysis. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1057–61. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1704-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neu A, Hofer SE, Karges B, Oeverink R, Rosenbauer J, Holl RW. Ketoacidosis at diabetes onset is still frequent in children and adolescents: a multicenter analysis of 14,664 patients from 106 institutions. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1647–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hekkala A, Knip M, Veijola R. Ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children in northern Finland: temporal changes over 20 years. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:861–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallare JT, Cordice CC, Ryan BA, Carey DE, Kreitzer PM, Frank GR. Identifying risk factors for the development of diabetic ketoacidosis in new onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2003;42:591–7. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker JM, Goehrig SH, Barriga K, Hoffman M, Slover R, Eisenbarth GS, et al. Clinical characteristics of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes through intensive screening and follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1399–404. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler C, Schober E, Ziegler AG, Holl RW. Markedly reduced rate of diabetic ketoacidosis at onset of type 1 diabetes in relatives screened for islet autoantibodies. Pediatric diabetes. 2012;13:308–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triolo TM, Chase HP, Barker JM. Diabetic subjects diagnosed through the Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1 (DPT-1) are often asymptomatic with normal A1C at diabetes onset. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:769–73. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanto-Salonen K, Kupila A, Simell S, Siljander H, Salonsaari T, Hekkala A, et al. Nasal insulin to prevent type 1 diabetes in children with HLA genotypes and autoantibodies conferring increased risk of disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1746–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]