Abstract

Prospective memory involves remembering to do something at a specific time in the future. Here we investigate the beginnings of this ability in young children (3-year-olds; Homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) using an analogous task. Subjects were given a choice between two toys (children) or two food items (chimpanzees). The selected item was delivered immediately, whereas the unselected item was hidden in an opaque container. After completing an ongoing quantity discrimination task, subjects could request the hidden item by asking for it (children) or by pointing to the container and identifying the item on a symbol board (chimpanzees). Children and chimpanzees showed evidence of prospective-like memory in this task, as evidenced by successful retrieval of the item at the end of the task, sometimes spontaneously with no prompting from the experimenter. These findings contribute to our understanding of prospective memory from an ontogenetic and comparative perspective.

Keywords: Chimpanzees, children, prospective memory, comparative cognition, ape, development

Prospective memory (PM) refers to the process of anticipating and remembering to perform activities at a specific time in the future (McDaniel and Einstein 2007). Generally, prospective memory involves setting an intention that cannot be fulfilled at the present time, maintaining that intention across time, monitoring the environment for the right opportunity to fulfill the intention, and properly executing the intention at the appropriate time (e.g., Einstein and McDaniel 1990, 2005; Ellis 1996; Ellis and Freeman 2008; Kliegel, McDaniel, and Einstein 2000; Marsh, Hicks, and Landau 1998; Shallice and Burgess 1991). For example, an individual might remember that he needs to get milk on the way home from work, but cannot immediately fulfill that intention because he is in a meeting. He needs to maintain that intention, either consciously or not, throughout the remainder of the day and be prepared for the appropriate opportunity – driving by the store - to fulfill the intention. Finally he needs to successfully retrieve the retrospective component of the memory when the appropriate time comes – that is, he needs to remember that buying milk was the reason he stopped at the store. Together, these components comprise prospective memory performance.

Over the last two decades, much research has focused on prospective memory in normal and aging adult human populations, but relatively less is known about this ability in children and nonhumans. Nonetheless, some studies have provided compelling data in the search for the emergence of PM in children (e.g., Ceci and Bronfennbrenner 1985; Kliegel, Mackinlay, and Jager 2008; Kvavilashvili, Messer, and Ebdon 2001; Smith, Bayen, and Martin 2010). For example, Kliegel and Jäger (2007) tested 2- to 6-year-old children by having them name the picture on each card in a deck. The prospective task was to remember to put a specific card (i.e., the picture of the apple) into a box that was either placed directly in front of child or out of sight. Two-year-olds were not reliably above chance, but by three years of age, some participants successfully engaged prospective memory to complete the task. The authors also discussed the importance of assessing whether the subjects remembered the prospective intention accurately. A failure should only be considered meaningful if subjects actually remembered after the fact what they were supposed to do (but failed to execute it at the appropriate time). By questioning whether subjects actually remembered the task instructions at the end of the experiment, one can distinguish between whether they failed to act on the prospective intention when appropriate or whether they forgot the instructions entirely. In the aforementioned experiment, when specifically analyzing the performance of subjects who could remember the task instructions at the end of the experiment, three-year-olds were significantly impaired on the task compared to the older children (Kliegel and Jager 2007). This finding highlights this particular age as important for the emergence and development of early prospective memory.

In addition to increasing our understanding of the development of prospective memory in children, we were interested in creating an analogous task for nonhuman primates to gain comparative insights into this ability. Evidence for future-oriented behavior, such as planning, has also been documented in some nonhuman primates, including transportation of tools for future use by apes (e.g., Mulcahy and Call 2006; Osvath and Osvath 2008), sequence planning in chimpanzees and rhesus macaque and capuchin monkeys (e.g., Beran, Pate, Washburn and Rumbaugh 2004; Beran and Parrish 2012; Biro and Matsuzawa 1999), and anticipation of a future thirst state in monkeys (Naqshbandi and Roberts 2006). Although these studies all involved anticipating a future need, none included the four elements of encoding, retention, maintenance, and execution that are characteristic of prospective memory.

There have been several recent animal studies addressing some or all of these elements of human-like prospective memory. For example, a recent study of prospective memory in rats trained subjects on a temporal bisection task in which subjects judged time intervals as short or long. Half of the subjects received food after the task, and the other half did not. Subjects who received a post-task meal showed reduced sensitivity near the end of the task. In contrast, no deficits were observed in the group who did not receive a meal at the end (Wilson and Crystal 2012). The authors interpreted this deficit in performance as time-based prospective memory in which the test subjects remembered that food was going to be delivered at the end of the interval, and this disrupted performance on the ongoing task. A similar pattern of performance was found in an event-based version of this prospective memory task (Wilson, Pizzo, and Crystal 2013). Another study assessed whether monkeys could encode, store, and spontaneously retrieve a future response within the context of an ongoing computerized task (Evans and Beran 2012). In that study, monkeys remembered to make a joystick response to a unique stimulus if they observed a specific cue while they engaged in a two-choice discrimination task. Some monkeys in this study even anticipated making the prospective memory response when they saw the appropriate cue by moving their joystick in the direction of the prospective stimulus before it was made available.

Because these tasks do not capture all of the same elements often examined in human prospective memory studies, we designed a manual prospective memory task that incorporated the encoding, retention, maintenance, and execution components that are characteristic of human prospective memory (Beran, Perdue, Bramlett, Menzel and Evans 2012). A language-trained chimpanzee named Panzee was presented with a choice between two food items in her indoor enclosure. The unselected item was hidden indoors, and the selected item was scattered in an adjacent outdoor enclosure along with eight lexigram tokens (geometric shapes that referred to various food items). Panzee was given access to her outdoor enclosure to forage for her selected food item, and if she remembered to search out and return the token representing the unselected item hidden indoors within 30 minutes, she received that item as well. Panzee consistently remembered to retrieve and return the correct token when food was available indoors, but only after she had retrieved the outdoor food items, whereas on control trials involving no indoor food she rarely returned a token. This study provided evidence of human-like prospective memory, but relied on the unique rearing history of the subject who could report the identity of items using the lexigram board.

In an effort to broaden our comparative understanding of prospective memory, we developed a task that could be easily implemented with nonhuman animals without specialized training and with human children. Although we did take advantage of the language training of three of our subjects for portions of the study, the design could be effectively implemented in individuals without any such history, including one chimpanzee involved in the present study. We explored performance on a “simple” or “activity-based” prospective memory task in which an intention could be fulfilled after the completion of another task. An analogous real-world situation would be remembering to stop by the post office after completing the grocery shopping. This type of task has been implemented in lab settings by having adults remember to ask for the return of a personal item (e.g., wristwatch) (Cockburn and Smith 1991; Kliegel, McDaniel and Einstein 2000) and by having children remind the experimenter to retrieve a hidden puppet at the end of the session (Atance and Jackson 1999). Although many lab experiments involve more complex tasks, we selected this type of simple PM task to assess performance in our subjects to lessen instructional demands and make interpretation more straightforward.

In our study, if a participant failed to respond spontaneously after completion of the ongoing task, a series of scripted prompts was initiated during the retrieval process itself. These prompts were categorized into prompts regarding the prospective intention or the retrospective contents. This method contrasts with the standard approach of querying the subject after the completion of the entire experiment regarding the memory for the prospective intention. By doing so, we hoped to establish a real-time measure of the amount of environmental support necessary for successful retrieval in young children without relying too heavily on the verbal responses of children about the task demands, given our concurrent interest in comparing children to chimpanzees in this kind of test.

Such comparative approaches to understanding cognitive performance have an important role because it is often unclear how closely various cognitive competencies relate and interact within human development. The clearest example of this is the role of language in other cognitive competencies, including many processes such as perceptual experiences, various forms of memory processing and decision making. Another example is the role that cultural factors play in other psychological phenomena – as in the case of cultural norms and the value placed on self-control over impulsivity, or the role culture might play in cooperative versus competitive decision making behavior. For prospective memory, and its reliance on future-oriented processes such as planning, one might expect that language and culture play important roles in shaping the development of these capacities. Therefore, assessing PM performance in the absence of full-blown human language and culture (which 3-year old children have) by studying chimpanzees adds to our understanding of the manifestations and limitations of PM.

Human and nonhuman subjects were given the choice between two items. The selected item was delivered immediately, and the one that was not selected was put into an opaque container. This manipulation was included to address an important concern in the animal literature that is not directly related to the study of human PM. Specifically – some have contended that animals do not plan for future needs that are not presently motivating (Bischof 1978; Roberts 2002; Suddendorf and Corballis 2007; Tulving 2005). We created a situation in which subjects were relatively less motivated by the item that had to be remembered compared to the item that was chosen and immediately delivered. Although we will not address whether this manipulation effectively alleviated this motivational concern in the present study, it may have influenced some aspects of performance and should be mentioned and considered.

After choosing between the two items and receiving the one that was selected, subjects then engaged in an ongoing task – a quantity judgment task – to prevent rehearsal and impose a delay between the setting of the intention to get the less preferred (non-selected) item and the opportunity to fulfill that intention. If subjects could remember to request the other item at the end of the ongoing quantity discrimination task, this would be indicative of prospective-like memory ability that was sustained during competing task demands. The prospective component of the task involved remembering to request the contents of the container at the end of the other task. The retrospective component was remembering the identity of the item in the container. This was explicitly queried in the language-trained chimpanzees, and it was recorded whether children mentioned the name of the item or specifically referred to the toy. We also measured the degree to which environmental support (i.e., prompting from experimenter) was necessary to produce successful intention implementation in both species. The degree of environmental support, or prompting, was also divided into prospective and retrospective components to further investigate the subtle differences in performance.

Method

Participants

Children

Thirty-four 3-year-old children (35-44 months, M = 38 months; 22 males, 12 females) were recruited through a university’s participant list. According to parental report, the racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 70% white, 24% Black/African-American, 3% Asian, 3% mixed race, and 9% reporting Hispanic ethnicity. Direct measures of socioeconomic status were not obtained, but the sample was generally middle- to upper-middle class. Two children did not complete the procedure, and the data from another two children were excluded due to experimenter error – leaving a total of 30 participants for analysis.

Chimpanzees

Four chimpanzees housed at the Language Research Center at Georgia State University participated in this study: (Females: Lana – 41 years, Panzee – 26 years; Males: Sherman – 38 years, Mercury – 25 years old). All chimpanzees were housed together in the same building and spent time together in social groups daily, but they were observed separately during test sessions. Chimpanzees participated for preferred food treats. Otherwise, they were maintained on their normal diet of fruit, vegetables, and primate chow. No food or water deprivation was used. Three of the four animals (excluding Mercury) had been involved in language acquisition research in which they learned to associate geometric forms called lexigrams with different foods, locations, objects, and people (see Brakke and Savage-Rumbaugh 1995, 1996; Rumbaugh 1977; Rumbaugh and Washburn 2003; Savage-Rumbaugh 1986).

Procedures

The prospective memory task described here for the children and chimpanzees differs from many prospective memory tasks because the cue to perform the intended action is the completion of the concurrent quantity judgment task. For this reason, this task type is sometimes referred to as a “simple prospective memory” or “activity based PM task” (Kliegel, McDaniel and Einstein 2000). We chose to use this more naturalistic prospective memory task because it would presumably be readily understood by chimpanzees and children without much explicit training or instruction. Also, note that the quantity judgment task that was chosen to run concurrently with the prospective memory task was different from tests typically used with human participants because the chimpanzees were already familiar with this type of test. Finally, note that different reward items were used with the children and chimpanzees so that both species would be adequately motivated to participate, with the limitation that food items were not a feasible option for use in the university laboratory.

Children

Children were tested individually in a university lab room, and their behavior was video recorded for subsequent analysis by research assistants. Each child was tested only once in each task. Children participated in two tasks relevant to the present study: Prospective memory and quantity judgment. Additionally, subjects completed a delay of gratification and an imitation task within the same session, but these tasks are not reported in the present study.

Prospective memory task

The procedure involved two toys, which the children were later allowed to keep. Parents selected the two toys from an assortment of age-appropriate puzzles, cars, balls, and stuffed animals, so that both items would be of value to their particular child. A blue box (23cm × 28cm × 30cm) was constructed using cardboard and blue wrapping paper as the holding container during test trials. The experimenter first showed the children two toys, labeling and drawing their attention to each (e.g., “Look at this car! Look how I can roll it!”). The children were told they could take both toys home, but that they could choose one to play with now. After the children made a choice, the experimenter held onto the chosen toy in order to prevent losing their attention. The children were then told that the other, non-chosen toy was theirs to take home as well, and that they would get it when the game was over. The experimenter then put the non-chosen toy into a large blue box on a table that was visible to the children. In order to make it clear to the children that it would not be impolite to ask for the toy later, as the experimenter put the toys in the box, she told the children, “You might have to remind me to get this for you, because sometimes I forget. Make sure to tell me to give you toy when we are done.”

The experimenter then instituted an eight-minute delay. Approximately the first two minutes involved playing with the child’s chosen toy. Then, the children participated in the quantity judgment task for six minutes (see below). After the quantity judgment task, the experimenter said, “We’re all done. It’s time to go home.” If the children did not spontaneously say something about the concealed toy, the experimenter used a series of scripted, suggestive prompts until the children verbally remembered the toy (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The cues given to children or chimpanzees at the end of the quantity judgment task.

| Type of Prompt |

Number of Prompts |

Experimenter Cue | |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 | No prompt – spontaneous retrieval | |

| Children | Prospective | 1 | “Is there anything you were supposed to remember to do?” |

| 2 | Tapping and pointing to the box; | ||

| 3 | “Was there anything you were supposed to remember about this box?” | ||

| Retrospective | 4 | ‘What’s in this box?” | |

| 5 | “Can you guess?” | ||

| 6 | Child never remembered | ||

| Chimpanzees | None | 0 | No prompt – spontaneous retrieval |

| Prospective | 1 | “Do you need anything else?” | |

| Retrospective | 2 | “What’s in here?” while pointing to the container | |

| 3 | “What’s this?” after uncovering the food item |

The experimenter retrieved the toy from the box if the child said or did something to indicate remembering the toy, such as pointing to the box, or asking for their toy. The child did not have to specifically name the toy. If the children did not say anything about the toy, the experimenter retrieved the toy after all five prompts had been used. The toy was given to the child to take home.

Quantity judgment task

The experimenter dropped colored paperclips, one at a time, into two gift bags that were placed in front of the children. The clips were always dropped first into the bag to the left of the child, and then into the bag on the right. Different numbers of clips were always dropped into the two bags. Two predetermined orders were used, and these were counterbalanced between children. After the clips were placed, the experimenter asked the child, “Which one has more?” After the child made a choice, the experimenter poured out the paperclips from both bags into two separate piles, showing the child which one had more paperclips. After each trial, the child was verbally praised (e.g. “You picked the bag with more!”) or corrected (“Oh, I got more. Try to find the one that has more clips.”).

Chimpanzees

Chimpanzees were tested in their home cages. Individuals voluntarily separated for testing, but had visual and auditory access to social group members throughout each test session. Data were recorded by a single experimenter using pen and paper during the test (as is typically the practice in the chimpanzee laboratory). Because chimpanzees could not be given verbal instructions for the tasks, each chimpanzee was tested on multiple days to allow for learning of the task rules.

Prospective memory task

We used a test bench with a sliding tray to present the initial choice between two food items. Food items were presented in small clear bowls (approximately 15 cm in diameter). Food items included apples, bananas, bread, primate chow, coffee, soda, juice, M&Ms candies, peanuts, pears, strawberries, and sweet potatoes. For the three language-trained chimpanzees, only items that the subjects could name on the lexigram board were used for testing. Subjects were familiar with the test bench from previous studies. One of the food items was placed underneath an opaque container that was also familiar to subjects.

At the onset of a trial, the first experimenter selected two food options that s/he knew would be of interest to the chimpanzees and then presented subjects with a choice between those two food options on a test bench (from the list of items noted above). Subjects selected one item by pointing at it. The unselected food item was then moved to a nearby location and hidden under an opaque container. The container was out of direct line of sight from the chimpanzee (and the subject had to re-position themselves in order to point at it). Then the selected food item was given to the subject and consumed. At this point, the first experimenter left the test area and a second experimenter, who did not know what was in the opaque container, entered to begin the quantity judgment task (see description below). The quantity task lasted eight minutes and subjects completed between 6 and 14 trials during this period depending on their own pace of responding. After completion of the quantity task, the experimenter remained in the test area for an additional three minutes and responded to any vocal or physical cues from the subject. If the chimpanzee spontaneously pointed to the container, the experimenter asked the subject to name what was there (for the three language-trained chimpanzees) and then delivered the food item. If subjects pointed to a lexigram on the lexigram board, the experimenter asked “where?” If subjects pointed to the container (as opposed to the refrigerator or some other location), the item was given to the subject. If the subject did not engage in one of these behaviors spontaneously during the 3-minute period, the experimenter initiated a series of prompts (see Table 1). If the subject indicated anything about the food item (on the lexigram board or by pointing to the container) during these queries, the item was given to the subject.

Only one trial occurred per session for test trials and control trials. Ten sessions were completed over a two week period, followed by 3 control trials for each chimpanzee on three separate days in which no food item was hidden under the container. All other aspects of the procedure were the same for the control and test trials. At the outset of the control trials, Experimenter 1 presented subjects with a choice of one food item or an empty bowl, and the “unselected item” – always the empty bowl – was placed under the opaque container.

Quantity Judgment Task

The same test bench was used with the addition of two opaque metal containers into which food items (grapes) were dropped. Note that grapes were never used as the test item in the concurrent task.

The second experimenter sat across the test bench from the chimpanzee. The bench held two opaque metal cups, one on each end of the sliding tray, and the chimpanzee could not see into the cups while seated on the floor of the test enclosure. The experimenter began each quantity judgment trial by showing the chimpanzee that the two cups were empty. He then filled his hand with the number of grapes needed for the trial behind the bench, out of view of the chimpanzee. Quantity comparisons were drawn from a randomized list of all possible comparisons within the range of 1 to 5 items, with the exception that equal numbers of items could not be presented in both cups. The experimenter presented each trial by first dropping 1 to 5 grapes, one at a time, from a closed fist into the cup on the chimpanzee’s right from a distance of approximately 15 cm above the cup. He then moved his fist above the other cup and dropped the remaining grapes one at a time. After presenting each quantity, the experimenter slid the tray holding the cups to within reach of the chimpanzee. The chimpanzee received the grapes from the cup he/she pointed to, and the experimenter emptied the unchosen cup behind the bench. Given that performance on this task was not our primary variable of interest, and not something that we intended to analyze in this study, we did not incorporate standard controls against potential experimenter cuing such as using two or more experimenters (see Beran 2001, 2004; Beran and Beran 2004, for more exhaustive analyses of chimpanzee performance in this kind of test including with various controls against cuing).

Data Analysis

For each child and chimpanzee, a score was assigned for the number of prompts necessary for successful completion of the prospective memory task as well as the percentage of correct quantity judgment trials.

Results

Children

Three children would not play the quantity discrimination task, and the 27 remaining children were correct on an average of 55.3% of trials (SE = 3.7%, range = 25% to 100% correct). Thus, the task was sufficiently difficult to engage their attention and likely disrupted any continuous subvocal rehearsal of the intention to remember to get the second toy from the container. Video-coding was used to determine at what prompt each child responded, whether the child named the toy before seeing or receiving it, and what bag was chosen in the quantity discrimination task. Scoring agreement was assessed by re-coding a randomly-chosen 25% of trials with children by a scorer who was blind to the research questions. The agreement for the prospective memory task response was 100% [Cohen’s kappa (κ) = 1.0]. The two scorers agreed on the child’s choice for 86% of trials on the numerical judgment task (κ = .75).

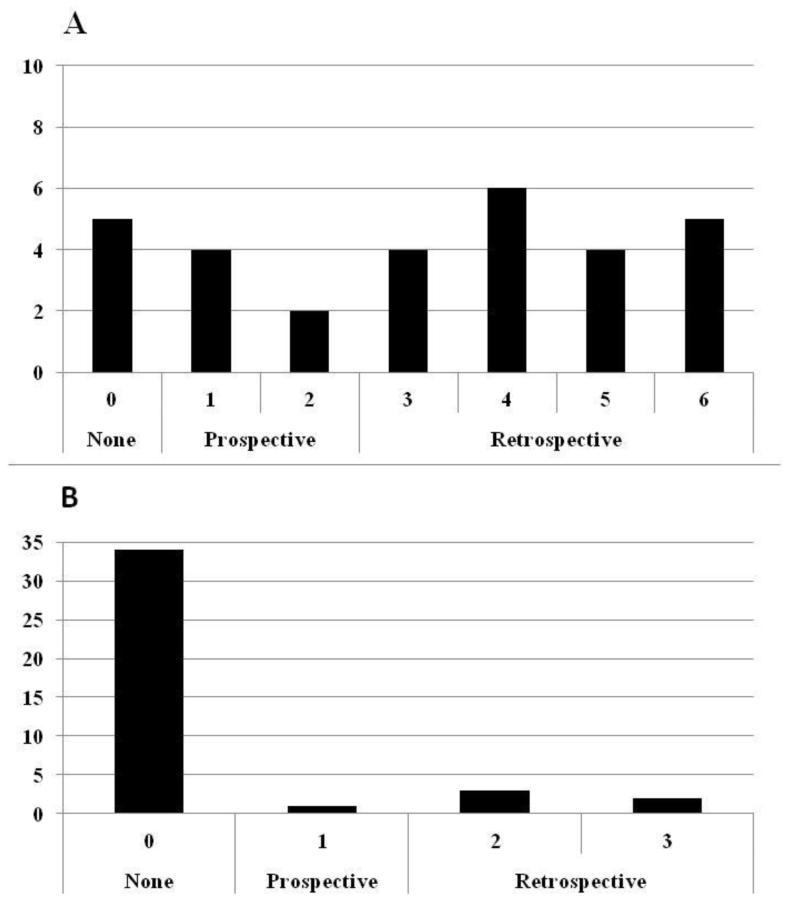

On the prospective memory task, spontaneous requests for the toy came from 5 of the 30 children, and 4 more remembered what to ask for with only minimal prompting, whereas approximately half of the children at this age needed very explicit prompts to give the information, if they ever did (see Table 1). Five children failed the retrospective component in that they could not correctly name the item even when explicitly asked (see Figure 1). That most children asked for the toy, even with several prompts, indicates that the children understood the task instructions given at the beginning of the session.

Figure 1.

Degree of environmental support needed for successful completion of the task. (A) shows the number of children falling into each category of response, and (B) shows the number of trials falling into each category for chimpanzees.

Chimpanzees

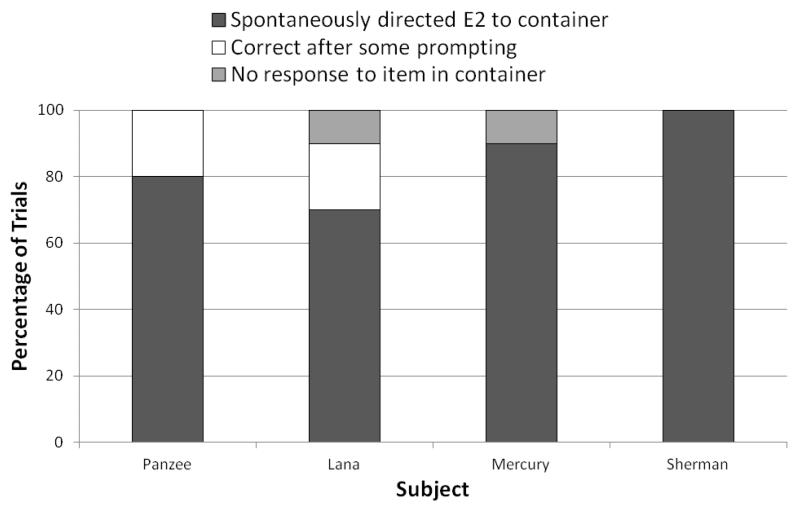

For the very first trial presented to the chimpanzee, only one out of four subjects spontaneously pointed to the container at the end of the quantity judgment task. Out of all 40 test trials, there were only two test trials in which subjects did not make any response to the item in the container at the end of the trial (even when prompted by the experimenter). On the trials in which subjects did make a response to the lexigram board and/or the container, 89.5% of these requests were completely spontaneous (34 out of 38). The remaining four trials were completed successfully with some prompting from the experimenter (see Figure 1, and Figure 2 for a breakdown of performance by individual). The three language-trained chimpanzees used the correct lexigram to name the food item on 27 out of 30 trials. All responses were recorded by the same experimenter in this portion of the testing.

Figure 2.

Distribution of chimpanzee response types in PM test trials for each individual.

Subjects maintained high levels of performance on the ongoing quantity discrimination task as well. On average, subjects were correct on 73.7% of trials (SE = .593%, range = 72.7% to 75.2% correct). However, although performance was high, it was not at ceiling, suggesting that the task was sufficiently engaging to prevent continuous rehearsal of the intention to request the food in the container.

Subjects only pointed to the empty container on 2 out of 12 control trials. A chi-square test of independence indicates that this proportion differs significantly from the number of spontaneous requests made in the test condition (34/40), χ2(1, N = 52) = 20.23, p < .001. On the remaining trials, subjects requested a food item on the lexigram board, but did not point to the bucket when asked, “where is it?” On average, subjects were correct on 81.1% of quantity discrimination trials during this phase of the experiment.

Discussion

Remembering that you need to do something at a later time requires prospective memory or the use of memory aids such as notes to yourself or alarm reminders. If you rely on memory alone, this requires forming the intention to perform the later action, maintaining that intention during ongoing activity, monitoring the environment for the proper time to act, and then implementing the intention at the proper time. We suggest that the performance by chimpanzees and three-year-old children in the present experiment captured many of these aspects of PM, although it was not as complex as most other lab based assessments (but see Atance and Jackson 1999; Kliegel et al. 2000). Both children and chimpanzees had the chance to obtain something that they wanted (perhaps with lower motivation than the item they actually selected from the two choices), but the non-selected item could not be obtained until later. Then, they were engaged in other activities that required attention and decision making resources. For chimpanzees, this ongoing activity rarely disrupted their post-test memory for retrieving the food item hidden in a container away from the test area. Chimpanzees seemed to find this task to be relatively easy, matching a previous report with one of these animals (Panzee; Beran et al. 2012). In chimpanzees, we also were able to separately identify prospective and retrospective failures to better understand performance in this domain. Remembering to request the container at the end of the test comprised the prospective component, while correctly naming the identity of the item in the container comprised the retrospective component. Chimpanzees were largely successful on both aspects of the task. Direct comparisons are limited because we could not verbalize the task rules to the chimpanzees, and thus required multiple test trials to allow for learning of the rules. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that, as a group, their initial performance was closely aligned to that of children.

Overall, children were more variable in their performance, and in most cases needed some help from the experimenter in order to obtain the toy that was hidden. However, some children succeeded with little or no help, showing that even at this young age children can remember to implement intentions to request items later, and can do so with distracting ongoing activity that prevents rehearsal of that intended action. But, it remains to be seen why other children struggled. One possibility is that they did not feel comfortable asking for the toy, but we believe this is unlikely given that the earliest cues from the experimenter often did not help, although those clearly were of the form to reassure the children that asking for the toy was acceptable. Another possibility is that children may not have much experience with the idea of “forgetful adults” and may have assumed that the adults would give them the toy later, and thus they did not place as high an emphasis on remembering to do that themselves. A more likely explanation is that children at this age are not yet proficient in remembering to do things later, which is consistent with previous research suggesting that prospective memory ability emerges around three years of age but is still impaired compared to older children (Kliegel and Jäger 2007).

The age of emergence is likely related to brain development, perhaps in regards to the prefrontal cortex. Research in humans suggests that the rostral prefrontal cortex – or Brodmann’s area 10 - is critically involved in prospective memory processing (for a review, see Burgess, Gonen-Yaacovi and Volle 2011). Although Area 10 of the prefrontal cortex is relatively larger in humans than chimpanzees, cytoarchitectonic techniques reveal similarities in the structure and organization of the cortical layers of the frontal pole in these two species (Semendeferi, Armstrong, Schleicher, Zilles, and Van Housen 2001). Given these structural similarities, it may be the case that these areas overlap functionally as well. Future research could address this possibility.

Another possible influence on performance in both children and chimpanzees was our use of a particular choice procedure at encoding – one that was included in an effort to address an important issue in the animal domain – and that was also included in the child version to provide maximum comparability between the experiments. Specifically, the manipulation was the presentation of two choice options to the subjects, with the qualification that the delayed reward was always the less preferred one. For chimpanzees, this was included as part of an effort to assess indirectly the claim that animals cannot remember future needs that are not presently most motivating (e.g., humans recognize an umbrella might be useful later if rain is expected, even though right now it is not useful; see Bischof 1978; Roberts 2002; Suddendorf and Corballis 2007; Tulving 2005). Thus, we immediately delivered the selected (and presumably preferred) item to the chimpanzees, so that the one they had to remember to request and name later was less preferred. They were very good at remembering to ask for these less preferred items later, after they finished the intervening task that also gave them preferred food items. Nonetheless, we do not claim that the chimpanzees were not motivated by the second food item, only that it was relatively less preferred. On the other hand, children may have been less motivated by a less preferred item. It was chosen by the child’s parent as something the child would be interested in, but it may not have been interesting to the child. The children may have shown even higher levels of remembering if only one preferred item was used.

It is also important to note that, for chimpanzees, these were edible rewards, whereas children were choosing between toys, and so it is possible that this difference in the type of reward led to some of the performance differences between the two groups, as a result of general motivation to get all of the rewards. The children may not have valued the unselected toy as much as chimpanzees valued the unselected food item. Further, chimps may value an unselected food at a high level. This difference in motivation or interest across species might have influenced performance on the prospective task.

Despite these differences, chimpanzees and children at this age both show some ability to encode, retain, and implement future actions using prospective memory. Establishing similar methodologies for children and nonhuman animals will open new avenues of research and theory that may ultimately improve our understanding of future-oriented cognition and prospective memory. For example, the results of the present study suggest that this simpler form of prospective memory can emerge independent of full-blown language and culture, suggesting an evolutionary basis for its early ontogeny.

The methodology used in the present study illustrates the potential to further close the gap between “human” and “nonhuman animal” prospective memory research. By doing so, we can better explore issues relating to implicit intention setting and spontaneous retrieval of PM intentions during everyday activity (Dismukes 2008). To date, much of the research in the animal domain has been done using tasks that address aspects of PM, but overall differ quite substantially from the human tasks. Although we chose to use an activity based PM task, much of the current research involves more complex designs that require interruption of an ongoing task to complete the prospective intention. Given the success of this simpler task in children and chimpanzees, a fruitful area of future research would be the development of more complex prospective memory tasks for use in comparative studies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (BCS - 0924811) and NICHD (P01HD060563), Georgia State University through the Second Century Initiative in Primate Social Cognition, Evolution and Behavior (2CI-PSCEB) and the Language Research Center. Bonnie M. Perdue was supported by the Duane M. Rumbaugh fellowship.

Contributor Information

Bonnie M. Perdue, Language Research Center, Georgia State University.

Theodore A. Evans, Language Research Center, Georgia State University

Rebecca A. Williamson, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University

Anna Gonsiorowski, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University.

Michael J. Beran, Language Research Center, Georgia State University

References

- Beran MJ. Summation and numerousness judgments of sequentially presented sets of items by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) J Comp Psychol. 2001;155:181–191. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.115.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) respond to nonvisible sets after one-by-one addition and removal of items. J Comp Psychol. 2004;118:25–36. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Beran MM. Chimpanzees remember the results of one-by-one addition of food items to sets over extended time periods. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Pate JL, Washburn DA, Rumbaugh DM. Sequential responding and planning in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) J Exp Psychol Anim B. 2004;30:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.30.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Perdue BM, Bramlett JL, Menzel CR, Evans TA. Prospective memory in a language-trained chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Learn Motiv. 2012;43:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Parrish AE. Sequential responding and planning in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Anim Cogn. 2012;15:1085–1094. doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0532-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof N. On the phylogeny of human morality. In: Stent G, editor. Morality as a biological phenomenon. Abakon; Berlin: 1978. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Biro D, Matsuzawa T. Numerical ordering in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes): Planning, executing, and monitoring. J Comp Psychol. 1999;113:178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Gonen-Yaacovi G, Volle E. Functional neuroimaging studies of prospective memory: what have we learnt so far? Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2246–2257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceci SJ, Bronfenbrenner U. “Don’t forget to take the cupcakes out of the oven”: Prospective memory, strategic time-monitoring, and context. Child Dev. 1985;56:152–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J, Smith PT. The relative influence of intelligence and age on everyday memory. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci. 1991;46:31–36. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.p31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dismukes K. Prospective memory in everyday and aviation settings. In: Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO, editors. Prospective memory: Cognitive, neuroscience, developmental, and applied perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 2008. pp. 411–431. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Normal aging and prospective memory. J Exp Psychol Learn. 1990;16:716–726. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Prospective memory: Multiple retrieval processes. Current Directions in Psychol Sci. 2005;14:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JA. Prospective memory or the realization of delayed intentions: A conceptual framework for research. In: Brandimonte M, Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, editors. Prospective memory: Theory and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JA, Freeman JE. Realizing delayed intentions. In: Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO, editors. Prospective memory: Cognitive, neuroscience, developmental and applied perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum; New York: 2008. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Evans TE, Beran MJ. Monkeys exhibit prospective memory in a computerized task. Cognition. 2012;125:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon N, Longard J, Bryson SE, Moore C. Making decisions about now and later: Development of future-oriented self-control. Cognitive Dev. 2012;27:314–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Plan formation, retention, and execution in prospective memory: A new approach and age related effects. Mem Cognition. 2000;28:1041–1049. doi: 10.3758/bf03209352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, Jäger T. The effects of age and cue-action reminders on event-based prospective memory performance in preschoolers. Cognitive Dev. 2007;22:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, Mackinlay R, Jager T. Complex prospective memory: Development across the lifespan and the role of task interruption. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:612–617. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Plan formation, retention, and execution in prospective memory: A new approach and age-related effects. Mem Cognition. 2000;28:1041–1049. doi: 10.3758/bf03209352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvavilashvili L, Messer D, Ebdon P. Prospective memory in children: The effects of age and task interruption. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:418–430. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh RJ, Hicks JL, Landau JD. An investigation of everyday prospective memory. Mem Cognition. 1998;26:633–643. doi: 10.3758/bf03211383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Prospective memory: An Overview and Synthesis of an Emerging Field. Sage Publications; Los Angeles: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Peake PK. The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:687–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy NJ, Call J. Apes save tools for future use. Science. 2006;312:1038–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1125456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqshbandi M, Roberts WA. Anticipation of future events in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) and rats (Ratus norvegicus): Tests of the Bischof-Kohler hypothesis. J Comp Psychol. 2006;120:345–357. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.4.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osvath M, Osvath H. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and orangutan (Pongo abelii) forethought: Self-control and pre-experience in the face of future tool use. Anim Cogn. 2008;11:661–674. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WA. Are animals stuck in time? Psychol Bull. 2002;128:473–489. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semendeferi K, Armstrong E, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Van Housen GW. Prefrontal Cortex in Humans and Apes: A Comparative Study of Area 10. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114:224–241. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200103)114:3<224::AID-AJPA1022>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T, Burgess P. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114:727–741. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Bayen UJ, Martin C. The cognitive processes underlying event-based prospective memory in school age children and young adults: A formal model-based study. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:230–244. doi: 10.1037/a0017100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf T, Corballis MC. The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behav Brain Sci. 2007;30:299–351. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X07001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72:271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Episodic memory and autonoesis: Uniquely human? In: Terrace H, Metcalfe J, editors. The missing link in cognition: Evolution of self-knowing consciousness. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 3–56. [Google Scholar]

- White JL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bartusch DJ, Needles DJ, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Measuring impulsivity and examining its relationship to delinquency. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:192–205. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, Crystal JD. Prospective memory in the rat. Anim Cogn. 2012;15:349–58. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0459-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, Pizzo MJ, Crystal JD. Event-based prospective memory in the rat. Curr Bio. 2013;23:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]