Abstract

This study was designed to investigate the inhibitory effects of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extract on the production of inflammation-related mediators (NO, ROS, NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Perilla frutescents (L.) Britton var. frutescens was air-dried and extracted with ethanol. The extract dose-dependently decreased the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species and dose-dependently increased antioxidant enzyme activities, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in lipopolysaccharide stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Also, Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extract suppressed NO production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6), NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2 were inhibited by the treatment with the extract. Thus, this study shows the Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extract could be useful for inhibition of the inflammatory process.

Keywords: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens, anti-inflammation, RAW 264.7 cells

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory response is characterized by the abundant production of NO and cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α. The pathogenesis of inflammation is a complex process between cells in the immune system, which is regulated by cytokine networks, and many pro-inflammatory genes. Furthermore, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages regulates inflammatory responses (1). Accordingly, these proinflammatory mediators have been considered important targets for the development of anti-inflammatory agents (2,3).

Macrophages play an important role in inflammatory disease through the release of factors that are involved in the inflammation response, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokines. Production of these macrophage mediators has been determined in many inflammatory tissues following exposure to many stimulants, including bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (4,5). LPS has been commonly used as an inflammatory stimulus in numerous studies involving macrophages. LPS has been reported to induce NO and expression of many inflammatory factors such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, through the activation of transcription factor NF-κB (6,7). Overproduction of NO induced by LPS through iNOS can reflect the degree of inflammation, and iNOS induction provides a means of assessing the effect of agents on the inflammatory process (8). NF-κB plays critical roles in the coordination of the expression of proinflammatory mediators and cytokines, including COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-1β (9).

Plant-derived phytochemicals with potential anti-inflammatory activity are an important and promising group of agents because of their low toxicity and apparent benefit in acute and chronic diseases (10). Previous studies of Perilla frutescens varieties indicated these plants contain antioxidant, anti-allergic and anti-tumor promoting substances (11–13); however, most of the studies have been accomplished specifically with Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton which is a Japanese plant called ‘chajoki’. In this study, we used the Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens which is an annual herbaceous plant found in northeast Asia, with thes Korean name of kkaennip. Both are vegetables and their appearances are similar, but Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton is a kind of herb, while Perilla. frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens belongs to the green vegetable group. Although Perilla. frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens has been studied for antitumor activity, diabetes and anti-oxidant activity (14–16), there is currently little data about its anti-inflammatory effects. Therefore, this study evaluated the anti-inflammatory effect of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of PFE

Perilla. frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens (P. frutescens) was purchased from Miryang, Korea. P. frutescens was air-dried for 3 days and then ground to 200 mesh. The ground P. frutescens was extracted 3 times with 70% ethanol, filtered, the ethanol removed under reduced pressure by rotary evaporator and the extracts were concentrated under vacuum (the extract is called PFE). While the processing the extract, we ensured LPS was not a contaminant.

Cell culture and treatment

Mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air. Cells in 96 well plates (2×104 cells/well) were treated with the PFE (10, 25, 50, 100 μg/mL) for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using a modified MTT assay (17). Briefly, cells (2×104 cells/well) were seeded in a 96 well plate and treated with PFE. Following treatment, 100 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline) was added to each well and further incubated for 4 hr at 37°C. Subsequently, 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to solubilize any deposited formazon. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured at 540 nm with a microplate reader.

Measurement of intracellular ROS level

Intracellular ROS levels were measured by the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) assay (18). DCF-DA can be deacetylated in cells, where it can react quantitatively with intracellular radicals to convert into its fluorescent product, DCF, which is retained within the cells. Therefore, DCF-DA was used to evaluate the generation of ROS in oxidative stress. Cells (2×104 cells/well) were seeded in a 96 well plate and pre-incubated with various concentrations (10, 25, 50, 100 μg/ mL) of PFE for 2 hr in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 2 hr of incubation, the cells were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Thereafter, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and then were incubated with 5 μm DCF-DA for 30 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader.

Measurement of antioxidant enzyme activities

Cells (2×104 cells/well) in a 96 well plate were pre-incubated with various concentrations (10, 25, 50, 100 μg/ mL) of PFE for 2 hr, then further incubated with LPS for 20 hr. The medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS. One mL of 50 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer with 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 7.0) was added and the cells were scraped. Cells suspensions were sonicated three times for 5 sec on ice each time, then cell sonicates were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20 min at 4°C. Cells supernatants were used for measuring antioxidant enzyme activities. The protein concentration was measured by using the method of Bradford (19) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined by monitoring the auto-oxidation of pyrogallol. A unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that inhibited the rate of oxidation of pyrogallol. Catalase activity was measured according to method of Aebi (20) by following the decreased absorbance of H2O2. The decrease of absorbance at 240 nm was measured for 2 min. Standards containing 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1 and 2 mmol/L of H2O2 were used for the standard curve. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-px) activity was measured by using the method of Lawrence and Burk (21). One unit of GSH-px defined as the amount of enzyme that oxidized 1 nmol of NADPH consumed per minute.

Measurement of NO level

Cells (2×104 cells/well) were seeded in a 96 well plate and pre-incubated with the indicated concentrations of PFE in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 2 hr. After 2 hr of incubation, the cells were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Thereafter, each 50 μL of culture supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent [0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethyle-nediamine, 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid] and incubated at room temperature for 10 min, The absorbance at 550 nm was measured in a microplate absorbance reader, and a series of known concentration of sodium nitrite was used as a standard (22).

Total and nuclear protein extracts

Cells were homogenized with ice-cold lysis buffer containing 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl, 1% v/v NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail. The cells were then centrifuged at 20,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were used as total protein extracts. For nuclear protein extracts, cells were homogenized with ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 15 mM CaCl2, 1.5 M sucrose, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Then, the cells were centrifuged at 11,000×g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were resuspended with extraction buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.42 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% v/v glycerol, 10 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail. The samples were shaken gently for 30 min and centrifuged at 21,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellets were used as nuclear protein extracts. The total and nuclear protein contents were determined by the Bio-Rad protein kit with BSA as the standard.

Western blotting

TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS and COX-2 expression and NF-κB p65 DNA binding activity were determined by Western blot analysis. Total protein for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, COX-2 protein levels and nuclear protein for NF-κB were electrophoresed through a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Separated proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a pure nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% skim milk solution for 1 hr, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C (23). After washing the blots, they were incubated with goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature. Each antigen-antibody complex was visualized using ECL Western blotting detection reagents and detected by chemiluminescence with LAS-1000 plus. Band densities were determined by an image analyzer ATTO densitograph and normalized to β-actin for total protein and nuclear protein.

Statistical analysis

The data were represented as mean±SD. The statistical analysis was performed using SAS software. Analysis of variance was performed using ANOVA procedures. Significant differences (p<0.05) between the means were determined by Duncan’s multiple range test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

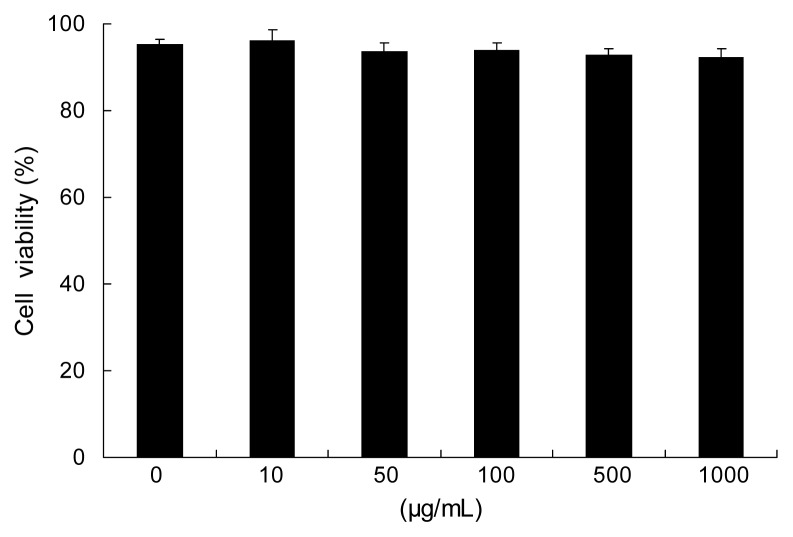

Cell viability

As shown in Fig. 1, RAW 264.7 cells viability showed that PFE had no effect on the viability at the concentrations of 0~1000 μg/mL.

Fig. 1.

Effects of PFE on viability in RAW 264.7 cells. Cells studied in 96-well plates (2×104 cells/well) were first incubated with and without indicated concentrations of PFE for 20 hr. Each value is expressed as mean±SD in triplicate experiments. PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

Intracellular ROS generation

Inflammatory reactions induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and chronic ROS production can induce a chronic inflammatory reaction (24). LPS significantly increases ROS generation in RAW 264.7 cells (p<0.05); however, PFE significantly reduced LPS-generated ROS in dose-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 2. PFE at concentrations of 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL reduced the intracellular ROS levels to 157.49%, 147.52%, 124.06%, 109.13%, respectively, compared with LPS alone. High ROS levels induced oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions, which can result in a variety of biochemical and physiological lesions. Thus ROS is important mediator that provokes or sustain inflammatory processes; neutralization of ROS by anti-oxidants and radical scavengers can attenuate inflammation (25).

Fig. 2.

Effects of PFE on intracellular ROS levels in LPS- stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells (2×104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were first incubated with or without indicated concentrations of PFE for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Untreated is negative control without LPS treatment. Each value is expressed as mean±SD in triplicate experiments. a-fValues with different alphabets are significantly different at p<0.05 as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

Antioxidative enzyme activities

It is commonly accepted that the central feature of inflammation is the activation of cells that synthesize and release large amounts of ROS (26). The importance of antioxidant enzymes is the prevention of oxidative stresses by scavenging of ROS. The antioxidant system is comprised of several enzymes, such as SOD, catalase and GSH-px (27). SOD is an enzyme that has anti-inflammatory capacity because of its ability to scavenge the superoxide free-radical (28). SOD catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anion (O2−) to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and H2O2 is further reduced to H2O by the activity of catalase or glutathione peroxidase. SOD plays a role as a second messenger in the production of inflammatory cytokines and SOD mimetics are known to inhibit cytokine production, including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 as shown in inflammatory models (29). As shown in Table 1, the activity of SOD was decreased by LPS, with untreated cells having 30.04±2.41 μM/mg protein while LPS-only cells had 14.35±3.16 μM/mg protein, an effect that was significantly reversed by the addition of PFE (p<0.05), with values ranging from 14.56±2.98, 20.15±5.29, 56.37±3.01, and 75.46±3.01 μM/mg protein with the addition of 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL PFE, respectively.

Table 1.

Effects of PFE on antioxidant enzyme activities in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells

| Untreated | PFE (μg/mL)+LPS (1 μg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 | ||

| SOD (μM/mg protein/min) | 30.04±2.41c | 14.35±3.16d | 14.56±2.98d | 20.15±5.29d | 56.37±3.01b | 75.46±4.12a |

| Catalase (μM/mg protein/min) | 0.29±0.02d | 0.18±0.01e | 0.29±0.06d | 0.37±0.09c | 0.52±0.18b | 0.73±0.16a |

| GSH-px (unit/mg protein) | 2.90±0.27b | 2.28±0.16bc | 2.52±0.27c | 2.57±0.20bc | 2.76±0.28b | 3.37±0.15a |

Cells (2×104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were first incubated with or without indicated concentrations of PFE for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Untreated is negative control without LPS treatment.

Values with different alphabets in a row are significantly different at p<0.05 as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test.

SOD: superoxide dismutase, GSH-px: glutathione peroxidase, PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

Catalase might cause anti-inflammatory effects by destroying hydrogen peroxide and by preventing formation of other cytotoxic oxygen species. Also, catalase affects the expression of genes influencing inflammation in vitro and in vivo(30). As shown in Table 1, the activity of catalase in the cells was significantly increased (p<0.05) by PFE treatment, with results ranging from 0.29±0.06 to 0.73±0.16 μM/mg protein, with the addition of 10 and 100 μM/mg PFE, respectively.

GSH-px are a family of intracellular antioxidant enzymes that reduce H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides by oxidizing glutathione. These enzymes play a critical protective role in the detoxification of ROS produced during inflammation (31). Normally, oxygen free radicals are excessively generated during the inflammatory process, and the various roles of antioxidant enzymes help to alleviate the inflammation response by overexposed ROS. In this experiment, the GSH-px activity in the RAW 264.7 cells showed a significant increase (p<0.05) upon treatment with PFE at 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL, resulting in 2.28±0.27, 2.57±0.20, 2.76±0.28, 3.37±0.15 unit/mg protein respectively.

Therefore, these data indicate that treatment of LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells with PFE enhances anti-oxidant enzyme activities that may be helpful in attenuating inflammation.

NO production

Nitric oxide (NO) mediates a variety of physiological and pathological processes, including inflammatory reaction. The increased production of NO is harmful, leading to a chronic inflammation condition (32). The most prominent phenomenon in the process of inflammation is the increase of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines. NO is known to act as an intracellular messenger that involves in promoting inflammatory responses in many cases (33,34). The effect of PFE on NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells is shown in Fig. 3. LPS significantly increased NO production in RAW 264.7 cells. In the presence of LPS, PFE significantly reduced NO production in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory activity on NO production of PFE was significantly decreased (p<0.05) with increasing PFE addition: with 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL PFE, NO production was 158.80%, 127.21%, 98.14%, 92.62%, respectively, compared with LPS treatment alone. In this study, PFE effectively decreased NO production, indicating PFE might be useful to suppress the inflammatory process.

Fig. 3.

Effects of PFE on NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Cells (2×104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were first incubated with or without indicated concentrations of PFE for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Untreated is negative control without LPS treatment. Each value is expressed as mean±SD in triplicate experiments. a-eValues with different alphabets are significantly different at p<0.05 as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

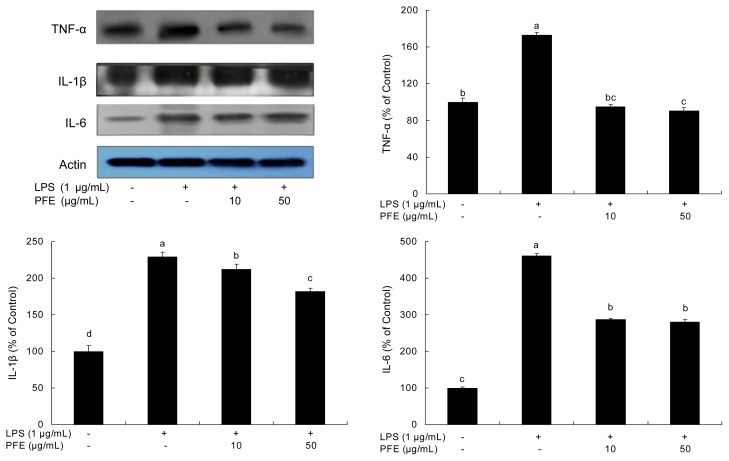

Effects of PFE on TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 expression

Inflammation is related to the overproduction of inflammatory mediators (NO) and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6. IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α are critical in the inflammatory network (35). LPS stimulates macrophages to release TNF-α, which then induces release of IL-1β and IL-6 (36). In this way, TNF-α induces inflammation (37). IL-6 is a pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesized mainly by macrophages. It plays a role in the acute-phase inflammation response (37). IL-1β is also considered to be a pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokine, primarily released by macrophages, and enhances the inflammatory response (38). The inhibitory effects of PFE on TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells are shown in Fig. 4. In this study, the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 was increased in LPS-stimulated cells. Treatment of the cells with PFE significantly decreased (p<0.05) the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.

Fig. 4.

Inhibitory effects of PFE on TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Equal amounts of cell lysates (30 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis and analyzed for TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 activity by Western blot analysis. The cells were first incubated with or without indicated concentrations of PFE for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Each value is expressed as mean±SD (n=3). a-dValues with different alphabets are significantly different at p<0.05 as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

In the present study, the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 increased when RAW 264.7 cells were stimulated by LPS but the production of these inflammatory factors was inhibited in the presence of PFE. These results indicate that PFE has an inhibitory effect on the inflammation process.

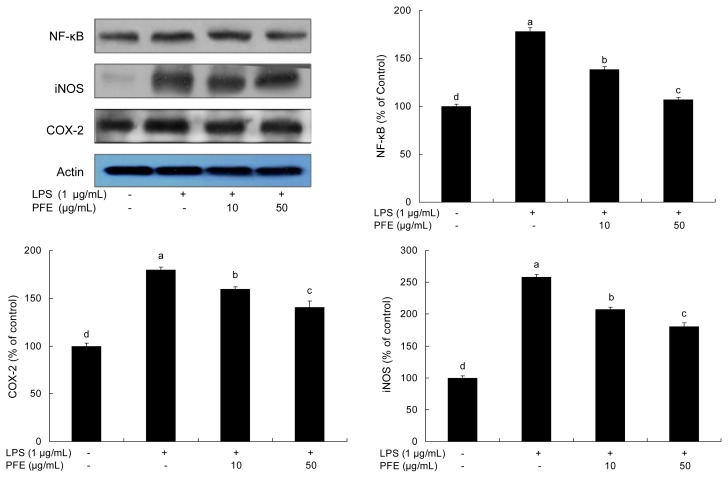

Effects of PFE on NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2 expressions

As shown in Fig. 5, the production of inflammatory mediators was significantly increased in the presence of LPS. Treatment with PFE suppressed LPS-stimulated expression of NF-κB p65 in RAW 264.7 cells. This suppression of PFE was correlated with down-regulation of iNOS and COX-2. NF-κB is a pleiotropic regulator of various genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses. It has been shown that NF-κB activation is a key factor in the production of iNOS, COX-2 and various cytokines in macrophages in response to LPS (39, 40). iNOS and COX-2 were increased in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, but, by treatment with PFE, those expressions were decreased (p<0.05) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5). iNOS and COX-2 are known to produce pro-inflammatory mediators, such as NO, at inflammatory sites. In particular, iNOS stimulates the oxidative deamination of L-arginine to produce NO, a potent pro- inflammatory mediator. COX-2 is another enzyme that plays a key role in the mediation of inflammation by stimulating the biosynthesis of prostaglandins (41). In this study, PFE restricts the production of inflammatory mediators such as NF-κB p65, iNOS and COX-2 expressions in RAW 264.7 cells, hence PFE may attenuate the process of inflammation.

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of PFE on NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2 levels in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Equal amounts of cell lysates (30 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis and analyzed for NF-κB, iNOS and COX-2 activity by Western blot analysis. The cells were first incubated with or without indicated concentrations of PFE for 2 hr, and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 20 hr. Each value is expressed as mean±SD (n=3). a-dValues with different alphabets are significantly different at p<0.05 as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. PFE: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton var. frutescens extracts.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that PFE decreased intracellular ROS levels and increased anti-oxidant enzyme activities. Also, PFE restricted production of NO, as well as decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and inflammatory mediators (iNOS and COX-2) in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Thus, this study suggests PFE might be an effective inhibitor of the inflammation process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by program for Regional Innovation System (RIS program) of the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (MKE) through Pusan National University Wellbeing Products RIS center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bendtzen K. Interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor in infection, inflammation and immunity. Immunol Lett. 1988;19:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(88)90141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li J. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo C. Alterations in nitric oxide production in various forms of circulatory shock. New Horiz. 1995;3:2–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim AR, Cho JY, Zou Y, Choi JS, Chung HY. Flavonoids differentially modulate nitric oxide production pathways in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:297–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02977796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon S, Lee Y, Park SK, Kim H, Bae H, Kim HM, Ko S, Choi HY, Oh MS, Park W. Anti-inflammatory effects of Scutellaria baicalensis water extract on LPS-activated RAW264.7 macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein SL, Sanghera JS, Lemke K, DeFranco AL, Pelech SL. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces ty-rosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen activated protein kinases in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14955– 14962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul A, Cuenda A, Bryant CE, Murray J, Chilvers ER, Cohen P, Gould GW, Plevin R. Involvement of mi-togen-activated protein kinase homologues in the regulation of lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of cyclo- oxygenase-2 but not nitric oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Cell Signal. 1999;11:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakama A. Chemoprevention with phytochem-icals targeting inducibles nitric oxide synthase. Food factors for health promotion. Forum of Nutrition Basel Karger. 2009;61:193–203. doi: 10.1159/000212751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung WY, Part JH, Kim MJ, Kim HO, Hwang JK, Lee SK. Xanthorrhizol inhibits 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate-induced acute inflammation and two- stage mouse skin carcinogenesis by blocking the expression of arnithine decarboxylase, cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase through mitogen-activated protein kinases and/or the nuclear factor-kappa B. Carci-nogenesis. 2007;28:1224–1231. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng L, Lozano YF, Gaydou EM, Li B. Antiox-idant activities of polyphenols extracted from Perilla frutescens varieties. Molecules. 2008;14:133–140. doi: 10.3390/molecules14010133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makino T, Furuta Y, Wakushima H, Fujii H, Saito K, Kano Y. Anti-allergic effect of Perilla frutescens and its active constituents. Phytother Res. 2003;17:240–243. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueda H, Yamazaki C, Yamazaki M. Inhibitory effect of perilla leaf extract and luteolin on mouse skin tumor promotion. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:560–563. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KH, Chang MW, Park KY, Rhee SH, Rhew TH, Sunwoo YL. Antitumor activity of phytol identified from perilla leaf and its augmentative effect on cellular immune response. Korean J Nutr. 1993;26:379–389. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim GJ, Kim YG, Kim HS. Effect of Perilla frutescens extract on the lipid peroxidation enzyme activities of serum in streptozotocin-induced rats. J Agric Tech & Dev Inst. 1999;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HS, Lee HA, Hong CY, Yang SY, Lee KW, Hong SY, Park SR, Lee HJ. Quantification of caffeic acid and rosmarinic acid and antioxidant activities of hot-water extracts from leaves of Perilla frutescens. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2009;41:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosmann T. Rapid colormetric assay for cellular growth and survival application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leloup C, Magnan C, Benani A, Bonnet E, Alquier T, Offer G, Carriere A, Periquet A, Fernandez Y, Ktorza A, Casteilla L, Penicaud L. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are required for hypothalamic glucose sensing. Diabetes. 2006;55:2084–2090. doi: 10.2337/db06-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Ann Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence RA, Burk RF. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:952–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’ Agostino P, Ferlazzo V, Milano S, La Rosa M, Di Bella G, Caruso R, Barbera C, Grimaudo S, Tolomeo M, Feo S, Cillari E. Anti-inflammatory effects of chemically modified tetracyclines by the inhibition of nitric oxide and inteleukin-12 synthesis in J774 cell line. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1765–1776. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim EK. PhD Dissertation. Pusan National University; Busan, Korea: 2008. Purification and characterization of anti-oxidative peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of venison. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapp A. Reactive oxygen species and inflammation. Hautarzt. 1990;41:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaporte RH, Sanchez GM, Cuellar AC, Giuliani A, Palazzo de Mello JC. Anti-inflammatory activity and lipid peroxidation inhibition of iridoid lamiide isolated from Bouchea fluminensis (Vell.) Mold. (Verbenaceae) J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halliwell B, Hoult JR, Blake DR. Oxidants, inflammation and anti-inflammatory drugs. FASEB J. 1988;2:2867–2873. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.13.2844616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao DC, Shi WB, Gou YL, Zhou XR, Tak YA, Zhou YK. Fatty acid-mediated intracellular iron translocation: a synergistic mechanism of oxidative injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1385–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulkey GB. The role of oxygen free radicals in human disease processes. Surgery. 1983;94:407–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasui K, Baba A. Therapeutic potential of super-oxide dismutase (SOD) for resolution of inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:359–363. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-5195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benhamou PY, Moriscot C, Richard MJ. Adenovirus-mediated catalase gene transcription reduces oxidant stress in human, porcine and rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1093–1100. doi: 10.1007/s001250051035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itzkowitz SH, Yio X. Inflammation and cancer IV. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the role of inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:7–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Król W, Czuba ZP, Threadgill MD, Cunningham BD, Pietsz G. Inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production in murine macrophages by flavones. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00237-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munhoz CD, Garcia-Bueno B, Madrigal JLM, Lepsch LB, Scavone C, Leza JC. Stress-induced neuroinflammation: mechanisms and new pharmacological targets. Bruz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:1037–1046. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2008001200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li XA, Everson W, Smart EJ. Nitric oxide, caveolae and vascular pathology. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2006;6:1–13. doi: 10.1385/ct:6:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qureshi N, Vogel SN, Van Way C, Papasian CJ, Qureshi AA, Morrison DC. The proteasome: a central regulator of inflammation and macrophage function. Immunol Res. 2005;31:243–260. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:3:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beutler B, Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/ TNF-α primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:625–655. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinarello CA. Cytokines as endogenous pyrogens. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:294–304. doi: 10.1086/513856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu XD, Yang Y, Zhong XG, Zhang XH, Zhang YN, Zheng ZP, Zhou Y, Tang W, Yang YF. Anti-inflammatory effects of Z23 on LPS-induced inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 macrophage. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawrence T, Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willoughby DA. Possible new role for NF-κB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7:1291–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappaB and I-kappaB proteins: newdiscoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1994;305:253–264. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]