Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to examine the association between self-reported functional disability in depressed older adults and two types of executive function processes, attentional set shifting and reversal learning.

Methods

Participants (N = 89) were aged 60 or over and enrolled in a naturalistic treatment study of major depressive disorder. Participants provided information on self-reported function in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and completed the Intra–Extra Dimensional Set Shift test (IED) from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery, which assesses intra-dimensional attentional shifts, extra-dimensional attentional shifts, and reversal learning. Participants were categorized by the presence or absence of IADL difficulties and compared on IED performance using bivariable and multivariable tests.

Results

Participants who reported IADL difficulties had more errors in extra-dimensional attentional shifting and reversal learning, but intra-dimensional shift errors were not associated with IADLs. Only extra-dimensional shift errors were significant in multivariable models that controlled for age, sex, and depression severity.

Conclusions

Attentional shifting across categories (i.e., extra-dimensional) was most strongly associated with increased IADL difficulties among depressed older adults, which make interventions to improve flexible problem solving a potential target for reducing instrumental disability in this population.

Keywords: depression, older adults, instrumental activities of daily living, disability, CANTAB, executive functions

Introduction

Depression is the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2004), which makes it important to identify factors that contribute to disabled function in this illness. In major depressive disorder (MDD), diminished capability in social, occupational, or other important areas of day-to-day activity can be caused by symptoms such as psychomotor retardation, fatigue, loss of interest in activities, and cognitive difficulties (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Cognitive difficulties contribute strongly to functional deficits in late-life depression, particularly in the domain of executive functions (Kiosses et al., 2000; Kiosses et al., 2001; Wilkins et al., 2010). Executive functions describe a set of higher order cognitive processes, including goal planning and organization, adaptive responses to feedback or contingency changes, response inhibition, and working memory (Chan et al., 2008); however, one criticism of research on executive functions is that it is often assessed with measures that could be influenced by multiple cognitive processes—including different aspects of executive functions—thereby providing limited insight into the individual processes that most specifically contribute to disability (Jefferson et al., 2006). Identifying specific components of executive functions that contribute to functional disability in late-life depression could lead to better models to assess, identify, and treat this major health issue.

The definition of functional abilities typically includes a distinction between deficits in basic activities of daily living (BADL), such as toileting, bathing, and dressing, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as shopping, housework, and managing finances. Impairments in IADL function are the focus of this paper because they are more frequently at issue among nondemented community-dwelling adults with depression (Alexopoulos et al., 1996; Steffens et al., 1999; Gallo et al., 2003), whereas impairments in BADL among depressed older adults are most often associated with medical comorbidities (Bruce & Hoff, 1994; Steffens et al., 1999) and motor limitations (Bennett et al., 2002). Successful performance of IADLs in any individual requires coordination of complex goal-directed activities (Bell-McGinty et al., 2002; Cahn-Weiner et al., 2002; Jefferson et al., 2006), which fits our previous definition of executive functions. Deficits in executive functions, such as problems in organizing information, initiating goal-directed activity, shifting attention between stimuli or tasks, or responding appropriately to changing task demands, are associated with impairment in IADLs in both demented and nondemented older adults (Bell-McGinty et al., 2002). Among the various aspects of executive functions, attentional shifting has shown the strongest association to IADL performance among healthy older adults (Bell-McGinty et al., 2002; Cahn-Weiner et al., 2002; Vaughan & Giovanello, 2010). Compared with research with these nondepressed older adult samples, neuropsychological correlates of IADL function in late-life depression have not been extensively studied, and thus far, IADLs have been most consistently associated with performance on a measure of initiation/preservation (Kiosses et al., 2000; Kiosses et al., 2001). Given the contribution of attentional shifting to IADL performance in nondepressed older adults, it is important to better understand the association of attentional shifting processes to IADL performance in late-life depression.

Although attentional shifting has been identified as a particularly salient aspect of executive functions, it may be deconstructed further. Two proposed components of attentional shifting are the intra-dimensional shift and the extra-dimensional shift (Owen et al., 1991). Intra-dimensional shifts require reallocation of attention to new exemplars of a category of stimuli that is currently or previously relevant (i.e., concept formation), whereas extra-dimensional shifts require reallocation of attention to a different category that was previously irrelevant (i.e., concept shifting). There is also a complementary but distinct process of reversal learning, which involves learning and changing a response when rules have been reversed; that is, a previously rewarded stimulus becomes unrewarded and irrelevant, whereas a previously unrewarded and irrelevant stimulus becomes rewarded. Deficits in intra-dimensional shift have been difficult to localize with respect to neuroanatomy of the prefrontal cortex because high numbers of these errors are uncommon outside of conditions with grossly disordered attentional function, such as severe chronic schizophrenia (Pantelis et al., 1999). In contrast, human and animal data support a neuroanatomical dissociation between extra-dimensional attentional shift and reversal learning, indicating that extra-dimensional attentional shift is associated with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Duncan & Owen, 2000; Rogers et al., 2004; Dias et al., 2006), whereas reversal learning is associated with orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (Rolls, 2000; Hampshire & Owen, 2006). Cognitive processes mediated by the OFC have received less attention as a cause of IADL disability than processes mediated by the DLPFC, despite findings that reduced OFC volume is associated with greater likelihood of self-reported disability in older adults (Taylor et al., 2003). Moreover, the role of the OFC in late-life depression is well-established, with depressed older adults exhibiting smaller OFC volumes, (Lai et al., 2000; Taylor et al., 2007), decreased neuronal density (Rajkowska et al., 1999), and greater lesion severity in the OFC (MacFall et al., 2001). Our review of the literature did not identify any studies investigating the association between reversal learning errors and functional deficits in depression; however, a study of individuals with Huntington’s disease found that a higher number of reversal errors was associated with a greater number of deficits in activities of daily living (Lawrence et al., 1999). Thus, reversal learning may provide unique information about the cognitive role of the OFC in the functional ability of depressed older adults.

The objective of the current study was to examine the association between self-reported functional disability and the individual components of intra-dimensional attentional shift, extra-dimensional attentional shift, and reversal learning in depressed older adults. We examined these cognitive processes in the context of a single cognitive task, the Intra–Extra Dimensional Set Shift test (IED) from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery (CANTAB), which involves separable tasks requiring intra-dimensional shifts, extra-dimensional shifts, and reversal learning. The design of this test is such that attentional set shifting and reversal learning are contingent upon each other as the test advances from stage to stage. The CANTAB IED test was modeled after testing paradigms in rodents and nonhuman primates that found reversal learning errors occurring in the OFC and extra-dimensional shifting errors in the DLPFC (Dias et al., 1996; Dias et al., 1997; Birrell & Brown, 2000; McAlonan & Brown, 2003). The IED task provides a potential behavioral distinction between a cognitive process typically mediated by the OFC (reversal learning) and a cognitive process typically mediated by the DLPFC (attentional set shifting) as well as a comparison of their relative associations to functional disability. We expected to find both extra-dimensional shift errors and reversal learning errors to be associated with higher rates of self-reported disability in depressed older adults; however, we anticipated that IADL disability would not be associated with intra-dimensional shift deficits in our population because of our expectation of relatively intact function in this domain.

Methods

Sample

All participants were enrolled in the National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored Conte Neuroscience Center for the Study of Depression in Later Life at Duke University Medical Center. All individuals were 60 years or older with a diagnosis of MDD at the time of enrollment. Individuals completed the IED at the enrollment study visit or at a subsequent study visit. Exclusion criteria at the time of enrollment included the following: (i) another major psychiatric illness, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or dementia; (ii) alcohol or drug abuse or dependence; (iii) primary neurologic illness, including dementia; (iv) medical illness, medication use, or sensory/motor limitation that would prevent the participant from completing neuropsychological testing; and (v) contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging. Individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders were not excluded, as long as MDD was the primary diagnosis. Individuals were screened for dementia at the time of enrollment on the basis of an established protocol that included review of a comprehensive clinical evaluation, consultation with referring physicians, and cognitive screening with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975). Any individuals performing below a score of 25 on their baseline MMSE were followed up through an established study protocol of reassessing cognition after an acute eight-week phase of treatment. Individuals whose MMSE scores remain below 25 are not followed longitudinally by the study; however, all individuals in the current study scored above this criterion at eight-week follow-up. This study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. After receiving a complete description of the study, all participants provided written informed consent.

Treatment protocol

Participants were treated by a geriatric psychiatrist on the basis of the Duke Somatic Treatment Algorithm for Geriatric Depression approach (Steffens et al., 2002), which follows a standardized naturalistic treatment algorithm. At the time of testing, 79 participants were taking at least one form of psychotropic medication, although there was missing medication data for nine participants (see Table 1). Among those with medication data, 31 were taking one medication, 24 were taking two medications, and 24 were taking three or more medications.

Table 1.

Psychotropic medications taken by study participants

| Medication class | n |

|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 53 |

| Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors | 25 |

| Benzodiazepines | 16 |

| Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | 16 |

| Tetracyclic antidepressants | 9 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 9 |

| Serotonin agonist and reuptake inhibitors | 9 |

| Sedative-hypnotics | 8 |

| Anticonvulsants | 7 |

| Stimulants | 5 |

| Atypicals | 5 |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | 3 |

| Analeptics | 1 |

| Melatonin receptor agonists | 1 |

| Number of medications | |

| one medication | 31 |

| two medications | 24 |

| three or more medications | 24 |

Treatment algorithm based on the work of Steffens et al. (2002). There are missing medication data on nine participants.

Depression assessment

Participants were assessed for depression severity by their treating psychiatrist using the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979). The MADRS is a 10-item scale of depression severity that is based on patient report and clinical observation. In this study, the MADRS was completed by the participant’s treating psychiatrist. Scores on the MADRS range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression symptoms.

Functional ability

At each study visit, a trained interviewer administered a standardized, computer-assisted interview, which included nine items modified from prior studies to assess self-reported functional abilities (Rosow & Breslau, 1966): (i) getting around the neighborhood; (ii) shopping for necessities; (iii) preparing meals; (iv) cleaning the house; (v) doing yardwork; (vi) keeping track of money; (vii) walking one-fourth of a mile; (viii) walking up and down a flight of stairs; and (ix) caring for children. The wording of all items followed a consistent pattern (“Can you …”), with a standardized three-option answer format (“yes” [coded 0], “with difficulty” [coded 1], or “no” [coded 2]). As performed in previous studies, a composite measure was constructed by summation of the individual item scores (Steffens et al., 1999). Following previous procedures (Taylor et al., 2003), we dichotomized items endorsed on the IADL measure as 0 items versus 1 or more items to reflect whether or not reported disabilities were present.

Neuropsychological testing

The IED was administered on a desktop computer with a touch-sensitive computer screen. The software package was CANTABeclispe (Cambridge Cognition Ltd, 2006), and the IED was administered in clinical mode. In this task, two stimuli (one correct and one incorrect) are displayed on the computer screen. Stimuli initially represent only one stimulus dimension apiece (e.g., shape), then two dimensions apiece (e.g., line and shape). Participants learn to select the correct dimensions on the basis of feedback from the computer, but the stimuli and/or rules are changed after a specific number of correct responses. The shifts in correct stimuli are initially intra-dimensional (e.g., within the shape dimension) and then later extra-dimensional, requiring a category shift (e.g., from the shape dimension to the line dimension). Reversal learning trials represent four of the nine stages, which proceed in sequential order.

The IED test terminates if the participant fails to learn the response criterion on any stage after 50 trials. As a result, not all participants complete all stages, especially those with greater cognitive deficits, and in theory, these individuals have less opportunity to make errors on some portions of the task. We applied the adjustment approach described in the CANTAB Administration Guide, which is to assign 25 errors for each failed stage, on the basis of the logic that 50 trials are needed to fail a stage, and half of the trials could be correct by chance alone. As a result, we used adjusted scores for the following variables of interest: (i) intra-dimensional shift errors; (ii) extra-dimensional shift errors; and (iii) reversal learning errors. For descriptive purposes, we also examined group differences in the number of stages completed, the proportion of individuals completing the task, and the proportion of participants failing to achieve criterion at the extra-dimensional shift stage (Owen et al., 1991).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were performed on demographic variables of age, sex, and education level, and also on depression severity. Appropriate t-tests or chi-square tests were used to estimate whether individuals with IADL impairments differed from individuals without IADL impairments on these characteristics. The t-tests were used to estimate differences in intra-dimensional shift errors, extra-dimensional shift errors, and reversal learning errors between the two groups. We also examined group differences in stages completed (t-test), the proportion completing the IED (chi-square), and the proportion failing the extra-dimensional shift stage (chi-square). We used multivariable logistic regression models to test whether the presence of IADL disability (functionally normal = 0, disability = 1) was predicted by performance on each of the three principal variables, controlling for depression severity and any demographic variables found to be significantly associated with disability in the bivariable tests. On the basis of a Bonferroni correction for the three principal tests, the threshold for statistical significance was p <0.017. Variables not significant in t-tests were not included in multivariable models.

Results

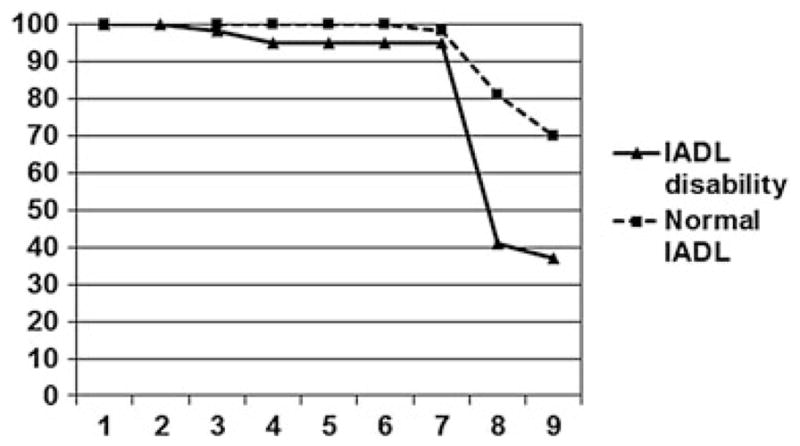

The sample consisted of 89 older depressed participants, 46 of whom reported no IADL problems and 43 of whom reported one or more IADL problems. Summary statistics are presented in Table 2. On the IED, the disability group performed worse than the functionally normal group on the following: (i) extra-dimensional shift errors; (ii) reversal learning errors; (iii) number of stages completed; (iv) percent completing the task; and (v) proportion completing the extra-dimensional shift stage (Table 2). Figure 1 shows that the performance of the disability group and the IADL normal group diverged at Stage 8, which is the extra-dimensional shift stage. There were no group differences in the number of intra-dimensional shift errors. With respect to demographic variables, individuals with functional disability were older, more likely to be female, and had higher depression severity on the MADRS, but they were not significantly different with respect to education level. As a result, age, sex, and MADRS score were included in the multivariate models on the basis of their significant association with disability, but education was not included.

Table 2.

Demographics and group comparisons

| No IADL problems | One or more IADL problems | Test value (df) | Effect | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| (N = 46) | (N = 43) | size | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.22 (5.17) | 71.93 (5.91) | t = 2.31 (87) | d = 0.49 | p = 0.0233 |

| % female (n) | 52.17 (24) | 81.40 (35) | χ2 = 8.49 (1) | OR = 4.01 | p = 0.0036 |

| MADRS, mean (SD) | 7.50 (8.48) | 11.91 (7.74) | t = 2.56 (87), | d = 0.54 | p = 0.0123 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.65 (2.68) | 14.86 (2.85) | t = −1.35 (87) | d = −0.30 | p = 0.1801 |

| Stages completed, mean (SD) | 8.39 (0.91) | 7.58 (1.48) | t = −3.08 (68.6) | d = −0.66 | p = 0.0030 |

| % IED completed (n) | 65.22 (30) | 37.21 (16) | χ2 = 6.98 (1) | OR = 3.16 | p = 0.0082 |

| % IED stage 8 completed (n) | 76.09 (35) | 41.86 (18) | χ2 = 10.81 (1) | OR = 4.42 | p = 0.0010 |

| ID shift errors, mean (SD) | 0.31 (0.51) | 1.73 (5.46) | t = 1.63 (39.6) | d = 0.38 | p = 0.1109 |

| ED shift errors, mean (SD) | 11.26 (10.09) | 19.12 (9.94) | t = 3.70 (87) | d = 0.78 | p = 0.0004 |

| Reversal errors, mean (SD) | 15.62 (13.50) | 24.95 (16.76) | t = 2.84 (83) | d = 0.62 | p = 0.0057 |

IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; df, degrees of freedom; SD, standard deviation; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale; IED, intra–extra dimensional set shift test; ID, intra-dimensional; ED, extra-dimensional; d, Cohen’s d; OR, odds ratio. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared using two-tailed t-tests when variances were equal and using the Satterthwaite t-test when variances were unequal.

Figure 1.

Percent of intra–extra dimensional set shift test (IED) completion by stage for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) disability and IADL normal. Nine stages of the IED are represented on the x-axis.

Multivariable models were consistent with bivariable results, except that reversal learning errors were not significantly different between groups in these models (p = 0.07). Including covariates of age, sex, and MADRS score, IADL disability was associated with more extra-dimensional shift errors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Maximum likelihood estimates for variables predicting disability status

| Parameter | df | Estimate | SE | Wald chi-square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | −7.5888 | 3.2305 | 5.5183 | p <0.05 |

| ED shift errors | 1 | 0.0667 | 0.0241 | 7.6522 | p <0.01 |

| Age | 1 | 0.0802 | 0.0447 | 3.2244 | ns |

| Sex (F = 2) | 1 | 0.4655 | 0.2762 | 2.8403 | ns |

| MADRS | 1 | 0.0680 | 0.0304 | 5.0087 | p <0.05 |

Modeled with higher value reflecting increased likelihood of disability. ED, extra-dimensional; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale; ns, not significant; df, degrees of freedom; SE, standard error.

In an exploratory analysis of our a priori results, we examined whether specific types of IADL deficits had stronger or weaker associations with the three principal error types on the IED. Rather than dichotomizing the groups by disability status, we examined each of the nine individual IADL items and the IADL total score as continuous variables, in separate Spearman correlations. We defined correlations testing the null hypothesis for each IED error type as a separate family of tests and used a Bonferroni correction of 0.005 for each of these three families. Extra-dimensional shift errors were significantly associated with five IADL items but three with Bonferroni correction: (i) “cleaning the house” (rs = 0.33); (ii) “doing yardwork” (rs = 0.30); and (iii) the IADL total score (rs = 0.33). Reversal learning errors were significantly associated with four items but one with Bonferroni correction that is “cleaning the house” (rs = 0.32). Intra-dimensional shift errors were associated with one individual IADL item, but it did not pass the Bonferroni threshold. Each of the significant associations at the zero-order level for both extra-dimensional shift and reversal learning remained significant in multivariate regression models controlling for age, sex, and depression severity.

Discussion

The current study found that depressed older adults who report disabilities in IADL show higher error rates on extra-dimensional attentional shifts and reversal learning but not on intra-dimensional attentional shifts; however, only the extra-dimensional shift was a significant contributor after controlling for depression severity and demographic covariates. Difficulties with extra-dimensional shifts of attention appear to be a robust performance indicator between depressed individuals with and without self-reported IADL deficits, as illustrated in stages completed on the IED (Figure 1). This is the first study we are aware of that uses a component approach to dissect how discrete cognitive processes within the executive function construct relate to IADL deficits in late-life depression. Our findings identify specific aspects of executive functions associated with functional disability in late-life depression, which are in addition to the initiation/perseveration findings reported by other researchers (Kiosses et al., 2000; Kiosses et al., 2001). These results provide additional evidence of ecological validity for attentional shift deficits as a predictor of difficulties in activities of daily living among older adults, in this case, specific to older adults with MDD.

The current study is consistent with studies of functional performance deficits in nondepressed older adults suggesting that self-reported IADL deficits are most associated with the attentional switching component of the executive function construct (Vaughan & Giovanello, 2010), but specifically dynamic across-category shifts. We would argue that difficulty identifying solutions outside of one’s current mental set (i.e., extra dimensionally) contributes to poor problem solving skills in complex activities of daily living. The current findings are also consistent with a study of women with melancholic and nonmelancholic depression, which found that the melancholic subtype was specifically associated with deficits in the extra-dimensional shift stage of the IED (Michopoulos et al., 2008). Deficits in extra-dimensional shift may be a deficit across different features of depression and not geriatric depression or disability per se. Future research can be helpful in better understanding whether there are specific behavioral features in the melancholic subtype that contribute to our observed relationship between extra-dimensional shift errors and difficulties in IADL.

The findings of the current study support the general notion that deficits in executive functions are associated with more IADL difficulty in late-life depression, but questions about the specificity of these relationships still remain. For instance, Mackin and Arean found that individuals with late-life depression showing deficits in financial capacity had greater difficulties in executive function but not specifically on attentional shifting tasks in their neuropsychological battery (Mackin & Arean, 2009). Our exploratory analysis, in contrast, did not find an association between executive functions and an item on self-reported money management, although it did find associations with specific items pertaining to upkeep of the home and yard. Differences between the two studies may lie in the fact that the Mackin and Arean study used a direct assessment of financial capacity and a broad neuropsychological assessment battery, whereas our study used a component analysis of a single well-defined cognitive task and a self report of functional performance. The approaches and research questions of the two studies are rather different, but they have a common aim of identifying more specific relationships between executive functions and functional ability in late-life depression. We hope that future research will continue to dissect the relationship between specific cognitive deficits and specific functional deficits among depressed older adults.

The clinical significance of the current study is that individuals who report difficulties with IADL performances are also likely to demonstrate an executive dysfunction in problem solving. Interventions focused on teaching problem solving skills are one potential strategy for reducing disability among depressed individuals with executive dysfunctions (Alexopoulos et al., 2003; Wilkins et al., 2010). Moreover, screening for IADL deficits is not time-consuming, and evidence of such deficits may suggest the need for further neuropsychological assessment. There is also a clinical significance in the status of IADL deficits as a diagnostic criterion for dementia. Research shows that executive function deficits predict the most rapid decline in IADL performance among nondepressed older adults (Cahn-Weiner et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007), and research shows that attentional shifting deficits on the Trail Making B task in late-life depression predict later development of dementia (Potter et al., in press); thus, the combination of deficits in IADLs and on attentional shift tasks may be an indicator of individuals with late-life depression who are at higher risk of dementia.

The current study has several potential limitations. One is that IADL ability was assessed by self-report rather than with a direct assessment of performance. Direct assessment of IADL would be a useful way to validate the current findings, although the relationship between self-rated disability and objective cognitive performance is well-established by this study and previous ones (Naismith et al., 2007). It is also not clear based on existing research that performance on direct assessments of IADL has better predictive validity for relevant outcomes such as treatment response. We also note that although the IED is well studied with regard to the underlying functional neuroanatomy of extra-dimensional shifting in the DLPFC and reversal learning in the OFC (Duncan & Owen, 2000; Rolls, 2000; Dias et al., 2006; Hampshire & Owen, 2006), our study does not have direct structural or functional brain imaging to corroborate this. We also studied a sample of individuals who are ambulatory and healthy enough to participate in a longitudinal treatment study. The relationships among functional disability, cognitive performance, and depression may be different among individuals who are less ambulatory or who have a high burden of physical disability or medical illness. Another limitation is that participants were enrolled in a naturalistic treatment study designed to optimize individual treatment response and were thus treated with several different psychotropic medications and combinations thereof. In this respect, our sample is more similar to the general population of depressed older adults treated in their community than samples from single-agent trials. Although we are constrained in our ability to analyze potential medication effects, we believe it unlikely that medication differences would have a systematic effect on the relationship between executive functions and disability, given the research suggesting that most antidepressant medications have small-to-nonexistent effects on cognitive performance (Podewils & Lyketsos, 2002; Siepmann et al., 2003).

Conclusions

We found that deficits in shifting attention across conceptual categories predict deficits in IADL among older adults with geriatric depression, most likely in conjunction with underlying abnormalities in the structure and/or function of the DLPFC. Future research may further specify the types of functional activities that are most susceptible to deficits in attentional shifting and their potential longitudinal consequences.

Key point.

Disability in IADL among depressed older adults is most associated with deflcits in attentional shift across categories (i.e., extra-dimensional).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants: R01MH054846, P50MH060451, K23MH087741, and K24MH070027.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this research study.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Arean P. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Vrontou C, Kakuma T, et al. Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:877–885. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Associaiton; Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Bell-McGinty S, Podell K, Franzen M, et al. Standard measures of executive function in predicting instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:828–834. doi: 10.1002/gps.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HP, Corbett AJ, Gaden S, et al. Subcortical vascular disease and functional decline: a 6-year predictor study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1969–1977. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4320–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Hoff RA. Social and physical health risk factors for first-onset major depressive disorder in a community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:165–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00802013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn-Weiner DA, Boyle PA, Malloy PF. Tests of executive function predict instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling older individuals. Appl Neuropsychol. 2002;9:187–191. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0903_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn-Weiner DA, Farias ST, Julian L, et al. Cognitive and neuroimaging predictors of instrumental activities of daily living. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:747–757. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge Cognition Ltd. CANTABeclipse Software User Guide. Cambridge Cognition Ltd; Cambridge, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Shum D, Toulopoulou T, et al. Assessment of executive functions: review of instruments and identification of critical issues. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23:201–216. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias EC, McGinnis T, Smiley JF, et al. Changing plans: neural correlates of executive control in monkey and human frontal cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociation in prefrontal cortex of affective and attentional shifts. Nature. 1996;380:69–72. doi: 10.1038/380069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociable forms of inhibitory control within prefrontal cortex with an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sort Test: restriction to novel situations and independence from “on-line” processing. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9285–9297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, Owen AM. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:475–483. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01633-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rebok GW, Tennsted S, et al. Linking depressive symptoms and functional disability in late life. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:469–480. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001594736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Owen AM. Fractionating attentional control using event-related fMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1679–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Paul RH, Ozonoff A, et al. Evaluating elements of executive functioning as predictors of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JK, Lui LY, Yaffe K. Executive function, more than global cognition, predicts functional decline and mortality in elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS, Murphy C. Symptoms of striatofrontal dysfunction contribute to disability in geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:992–999. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<992::aid-gps248>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Murphy C, et al. Executive dysfunction and disability in elderly patients with major depression. Am J Ger Psychiatry. 2001;9:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai TJ, Payne ME, Byrum CE, et al. Reduction of orbital frontal cortex volume in geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:971–975. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Sahakian BJ, Rogers RD, et al. Discrimination, reversal, and shift learning in Huntington’s disease: mechanisms of impaired response selection. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:1359–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFall JR, Payne ME, Provenzale JE, et al. Medial orbital frontal lesions in late-onset depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:803–806. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackin RS, Arean PA. Impaired financial capacity in late life depression is associated with cognitive performance on measures of executive functioning and attention. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:793–798. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlonan K, Brown VJ. Orbital prefrontal cortex mediates reversal learning and not attentional set shifting in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos I, Zervas IM, Pantelis C, et al. Neuropsychological and hypothalamic-pituitary-axis function in female patients with melancholic and non-melancholic depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naismith SL, Longley WA, Scott EM, et al. Disability in major depression related to self-rated and objectively-measured cognitive deficits: a preliminary study. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Roberts AC, Polkey CE, et al. Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:993–1006. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90063-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Barber FZ, Barnes TR, et al. Comparison of set-shifting ability in patients with chronic schizophrenia and frontal lobe damage. Schizophr Res. 1999;37:251–270. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Tricyclic antidepressants and cognitive decline. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:31–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GG, Wagner HR, Burke JR, et al. Neuropsychological predictors of dementia in late-life major depressive disorder. Am J Ger Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Wei J, et al. Morphometric evidence for neuronal and glial prefrontal cell pathology in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1085–1098. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Kasai K, Koji M, et al. Executive and prefrontal dysfunction in unipolar depression: a review of neuropsychological and imaging evidence. Neurosci Res. 2004;50:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:284–294. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepmann M, Grossmann J, Muck-Weymann M, et al. Effects of sertraline on autonomic and cognitive functions in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:293–298. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Hays JC, Krishnan KR. Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Ger Psychiatry. 1999;7:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, Krishnan KRR. The Duke somatic treatment algorithm for geriatric depression (STAGED) approach. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36:58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, O’Connor CM, Jiang WJ, et al. The effect of major depression on functional status in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:319–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WD, Macfall JR, Payne ME, et al. Orbitofrontal cortex volume in late life depression: influence of hyperintense lesions and genetic polymorphisms. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1763–1773. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WD, Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, et al. Smaller orbital frontal cortex volumes associated with functional disability in depressed elders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:144–149. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan L, Giovanello K. Executive function in daily life: age-related influences of executive processes on instrumental activities of daily living. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:343–355. doi: 10.1037/a0017729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins VM, Kiosses D, Ravdin LD. Late-life depression with comorbid cognitive impairment and disability: nonpharmacological interventions. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:323–331. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease. Vol. 2008 WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]