Abstract

This report describes a successful dilation of tracheal stenosis in a 16-year-old dog using a conventional endotracheal tube balloon. This technique should be considered as palliative treatment when owners decline other therapeutic options.

Résumé

Résultat à long terme de la dilatation du ballonnet-tube trachéal d’une sténose trachéale chez un chien. Ce rapport décrit une dilatation réussie d’une sténose trachéale chez un chien âgé de 16 ans à l’aide d’un ballonnet-tube trachéal conventionnel. Cette technique devrait être considérée comme un traitement palliatif lorsque les propriétaires refusent les autres options thérapeutiques.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Acquired tracheal stenosis may result from various disorders including neoplasia, inflammation, infection, and trauma (1–4). Clinical signs vary from exercise intolerance and mild inspiratory effort to life-threatening respiratory distress and cyanosis (3,4). The 2 most common treatments for tracheal stenosis are resection and anastomosis and stenting. The former is technically difficult and might be associated with complication and the latter requires special equipment and training (2,5).

Case description

A 16-year-old, neutered female, mixed breed dog, weighing 10 kg, was presented with the chief complaint of respiratory distress. The clinical signs were first noted 4 mo prior to arrival and included exercise intolerance and respiratory difficulties during excitement. During these 4 mo the dog was treated by the referral veterinarian with antibiotics with no improvement.

Upon arrival, the dog had severe inspiratory effort and cyanosis; she was immediately hospitalized in an oxygen cage. Due to progressive deterioration in respiratory effort the dog underwent general anesthesia using butorphanol (Morphasol 10 mg/mL; aniMedica GmbH, Baisensell, Germany), 0.2 mg/kg body weight (BW), SC, for premedication, ketamine (Clorketam Veterinary 10%; Vétoqinol, Lure, France), 5.0 mg/kg BW, IV, and diazepam (Assival 10 mg/2 mL; Teva, Godollo, Hungary), 0.5 mg/kg BW, IV, for induction. For maintenance, propofol (Propofol-Lipuro 1%; B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) was given IV to effect. Resistance was noted during intubation; however, immediately after placing the endotracheal tube, the inspiratory effort dramatically improved.

Complete blood cell count and serum creatinine concentration were unremarkable. Due to financial reasons and lack of owner compliance serum biochemistry was not conducted. Arterial blood gas analysis on room air after intubation, but with of 83.8 mmHg, no oxygen supplementation, revealed a PaO2 a PaCO2 of 42.7 mmHg, and a pH of 7.37 (at sea level). Before intubation, and during extubation, the larynx was evaluated for arytenoid function and for gross lesions; findings were unremarkable. Cervical radiographs (after removal of the endotracheal tube) revealed a marked narrowing of the trachea approximately 2 cm caudal to the hyoid apparatus (Figure 1). The diameter of the narrowing was estimated to be 5 mm, compared with a diameter of 12 mm for the normal trachea. At the end of the procedure the dog received 4 mg of Dexamethasone (Dexacort 4 mg/mL; Teva) IV. Following extubation there was a marked improvement in respiratory effort, most likely due to widening of the stenosis following intubation. Tracheoscopy, which was performed the same day, revealed abnormal tissue at the cranial trachea, 2 to 3 cm long, extending from the larynx distally and causing severe stenosis (3 to 4 mm in diameter). Differential diagnosis included inflammatory process, neoplastic process, or fibrotic tissue. During tracheoscopy, samples were obtained using swabs and touch smears were performed, but were non-diagnostic.

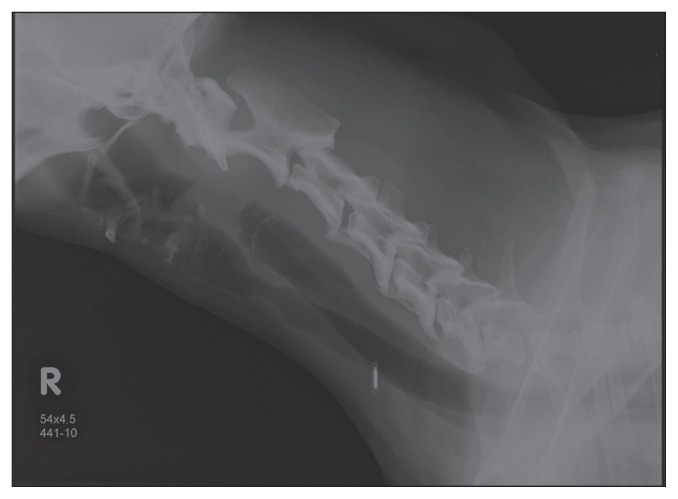

Figure 1.

Right lateral projection obtained at presentation, demonstrating a severe narrowing of the tracheal lumen with soft tissue opacity approximately 2 cm caudal to the hyoid apparatus.

The dog was discharged but the owners were warned that the relief was expected to be temporary and further diagnostics and treatment such as surgery or stenting were recommended. The owners declined any other diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, however, due to financial constraints.

Six months later the dog was presented again for a surgical and oncology consultation due to the recurrence of clinical signs. During the last 2 mo there had been progressive deterioration in respiratory effort, which was most notable with minimal activity and upon excitement. On presentation, the dog was tachypneic (respiratory rate: 120 breaths/min), and had a marked inspiratory effort. On thoracic and cervical radiography, a severe narrowing was noted approximately 2 cm caudal to the hyoid apparatus, at the same previous location. The diameter of the stenosis as revealed by radiographs was ~5 mm, comparable to the previous estimate (Figure 2). Additionally, an alveolar pattern was present at the right middle, left cranial, and caudal lung lobes. Main differential diagnoses for the alveolar pattern included non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema secondary to the upper airway obstruction, or pneumonia.

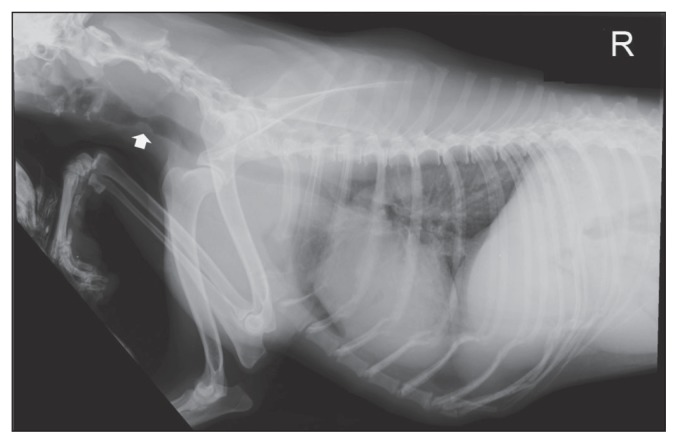

Figure 2.

Right lateral projection obtained 6 months after initial intubation which widened the stenosis, demonstrating recurrence of the stenosis at the same previous location.

On repeated tracheoscopy, a 3 to 4 mm diameter stenosis was noted, approximately 2 to 3 cm caudal to the larynx. The mucosa cranial to the stenosis was thick and edematous. Resection and anastomosis was considered as the treatment of choice despite the concern for dehiscence. Due to financial constraints, the owners declined any surgical option, including stenting across the stenosis; therefore, palliative treatment with balloon dilation was performed. The balloon size was selected based on the degree of narrowing and the diameter of the normal cervical trachea. To prevent bleeding into the lungs during the procedure, a 3.5 mm internal diameter endotracheal tube was initially inserted through the stenosis and the balloon was fully inflated. A second, 5.5 mm internal diameter endotracheal tube was then inserted over the small endotracheal tube and its balloon was positioned at the level of the stenosis under endoscopic guidance (Figure 3). After placing both endotracheal tubes and before inflating the balloon, the stenosis was inspected and the balloon was inflated for 2-minute intervals under endoscopic guidance to ensure that there was not much damage to the mucosa. The amount of bleeding was minimal to moderate and when the bleeding ceased, the dog was extubated and the stenosis site was evaluated. The stenosis was markedly dilated compared with the diameter prior to the procedure (Figure 4). Following the procedure, dexamethasone (Dexacort 4 mg/mL; Teva), 0.2 mg/kg BW, IM, was administered to minimize recurrence. After extubation the dog was monitored for signs of respiratory distress and was discharged when completely recovered and breathing normally. Due to the diameter of the stenosis it is likely that it was partly dilated by passing the larger endotracheal tube and was further dilated by inflation of the endotracheal tube balloon at the stenosis site. The assessment was that the stenosis rather than the abnormal lung pattern played a larger role in the respiratory difficulty, because after the dilation procedure, the dog was breathing normally without effort. Further diagnostics were not conducted at the owner’s request. Biopsies obtained via endoscopy from the abnormal tissue at the stenosis site were consistent with neutrophilic tracheitis and fibrosis with no evidence of a neoplastic process.

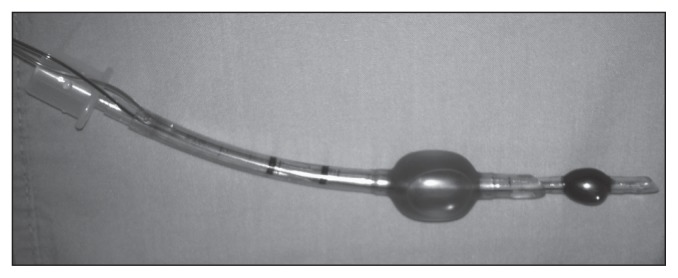

Figure 3.

Demonstration of the 2 endotracheal tubes used in this procedure. A smaller tube of 3.5 mm internal diameter was inserted first through the stricture and was dilated (smaller/blue balloon) to secure the airways in case of bleeding during stricture dilatation. After balloon inflation of the 3.5 mm endotracheal tube, a 5.5 mm tube (larger/red balloon) was inserted over the smaller endotracheal tube and the balloon was gradually inflated at the stenosis site.

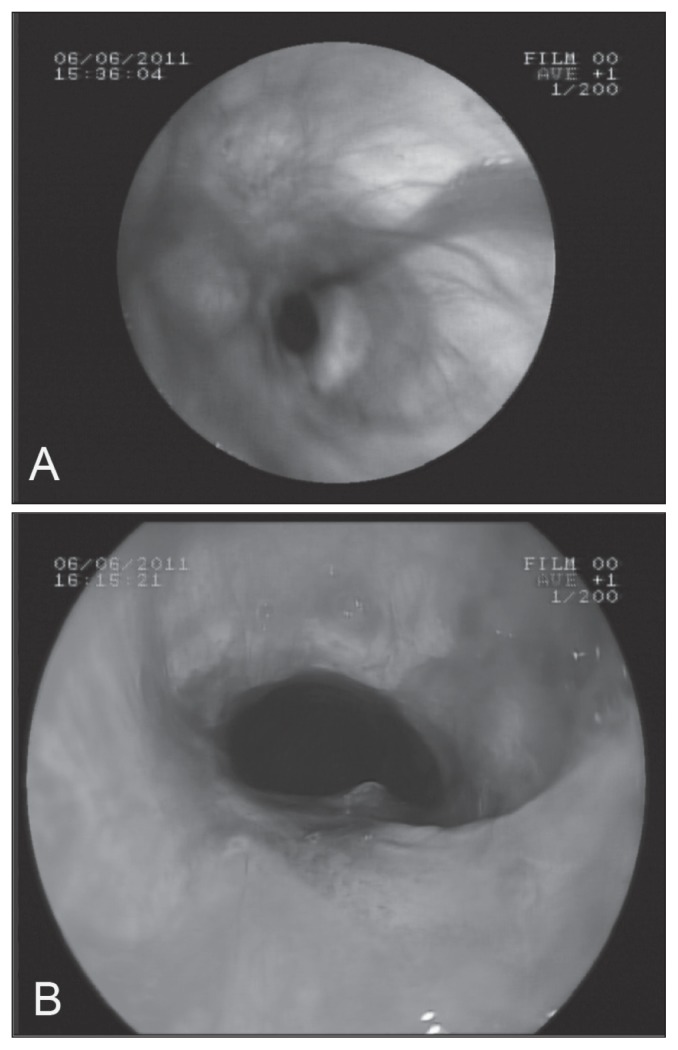

Figure 4.

Bronchoscopic image of the site of the tracheal stricture prior (A) and immediately after (B) dilatation using the endotracheal balloon.

Eleven months later the dog was presented with a complaint of respiratory distress and hemoptysis. History revealed that the dog had been free of clinical signs until 2 mo prior to presentation, during which the dog suffered from periods of increased respiratory effort, which had become worse during the last few days. At arrival, tracheoscopy was performed and revealed a 2 to 3 mm diameter tracheal stenosis at the previous site. It was decided to balloon dilate the stenosis again using the same technique, as other options were declined by the owners. Following the procedure the diameter of the trachea was 7 to 9 mm and the dog was breathing with no respiratory effort.

A week later the dog was presented with a complaint of decreased appetite, coughing, and 1 episode of syncope. Chest radiographs revealed a diffuse alveolar pattern, predominantly in the cranial lung lobes, likely due to pneumonia, non-cardiogenic edema, or neoplasia. The diameter of the stenosis was about 8 mm, unchanged compared with its diameter following the last procedure, and the clinical signs were therefore assessed to be unrelated to the stenosis. On broncho-alveolar lavage, red blood cells, white blood cells, and a few epithelial cells were seen; however, a cell count was not performed. There was no evidence of a neoplastic process or pneumonia. Further diagnostics were declined for financial reasons. At the owners request the dog was discharged with treatment which consisted of oral antibiotics; Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin 250 mg; Smith Kline Beecham PLC, Brantford, UK), 1/2 a tablet twice a day, Ofloxacin (Oflodex 200; Dexcel, Or-Akiva, Israel), 1 tablet once a day, and a bronchodilator: Theophylline (Theotrim 100; Trima, Maabarot, Israel), 1 tablet twice a day. The dog was presented again 6 d later with neurological signs of head pressing, bumping into walls, and ataxia. At this point the dog was euthanized at the owner’s request.

Discussion

Dilation of tracheal stenosis as a palliative measure for segmental tracheal stenosis in a dog using a new technique is described. Tracheal stenosis, although uncommon, may be seen with neoplastic diseases, inflammatory processes, congenital abnormalities, previous tracheal surgery, endotracheal tube pressure necrosis, or scar formation from previous trauma, abscesses, foreign bodies, vascular anomalies, granulomas, and extratracheal compression (1–4).

Clinical signs commonly consist of stridor, respiratory distress, and subsequent cyanosis. When the stenosis limits luminal size to approximately 50% to 75% of normal diameter, respiratory distress becomes obvious at rest and cyanosis develops with minimal exercise (6). The diagnosis is usually based on radiographs and tracheoscopy (3,4).

Treatment of tracheal stenosis may be either medical or surgical. Resection and anastomosis of up to 50% of the trachea in an adult dog can be performed (6). Surgical resection and anastomosis is the treatment of choice for tracheal stenosis, especially when tracheal neoplasia is diagnosed, not only to eliminate the obstruction, but also to resect the neoplastic tissue. Resection and anastomosis is a relatively complicated, invasive procedure, and can result in significant morbidity including dehiscence, tracheal stenosis or necrosis, pneumothorax, and laryngeal paralysis (7). In the present case, the risk for dehiscence was considered high since the tissue from the stenosis site cranial to the larynx was abnormal and thus less likely to heal well (8,9).

A permanent tracheostomy is another surgical option for proximal cranial segmental tracheal stenosis, and is indicated when upper airway obstruction is prolonged or cannot be relieved. Complications associated with permanent tracheostomy in dogs and cats include infections, stenosis, and obstruction of the stoma with a foreign body, skin folds, or mucous secretions (10). In this case, a permanent tracheostomy was offered to the owners; however, because of immediate and dramatic improvement after the first intubation, most likely due to dilation of the stenosis following intubation, the owners requested that surgical intervention be postponed until clinical signs recurred.

Tracheal stent placement is becoming more common in companion animals; however, it has been typically reserved for tracheal collapse in dogs. Intraluminal tracheal stent is a reasonable treatment option for tracheal stenosis (7), but it was not performed in the current case due to financial constraints. Complications associated with intraluminal tracheal stenting in dogs include stent migration, collapse, breakage or deformation, abscess formation, excessive granulation tissue formation, tracheitis, coughing, pneumomediastinum, pneumonia, and death (7,11).

Another nonsurgical option is tracheal bougienage, which is used with reasonable success in humans as primary therapy for stenosis or as an initial therapy to allow urgent relief of airway obstruction and to make dilation and stent placement simpler and safer. The bougienage can be done using designated equipment such as an angioplastic balloon catheter, valvuloplasty catheters, or a fogarty catheter (3). Alternatively, the stenosis can be dilated using an endotracheal tube balloon (12) as was done in this case. In both procedures repeated treatments may be needed and the treatment may be combined with steroids and stenting. Nomori et al (12) used a conventional endotracheal tube balloon as an initial treatment prior to stent placement with adequate dilation and without complications. In this case, steroids were administered following the first visit and first balloon dilation procedure in an attempt to decrease the risk for recurrence. The use of steroids has been described following esophageal stricture dilation (13); however, there is limited evidence to support their use in tracheal stricture dilation.

We emphasize that the procedure is palliative and that the stenosis is likely to recur; therefore, multiple dilations may be required. Retrospectively, the final cost of the 2 balloon dilations might approach the cost of surgery. Surgery was presented to the owner each time the stenosis recurred but was rejected due to the lower cost of balloon dilation, the success of the previous dilation procedure, and that the potential complication of stenosis recurrence in both procedures (7).

Once clinical signs recurred in this dog it was decided to dilate the stenosis again using an endotracheal tube balloon, considering the dog’s age and the good and relatively long-lasting response to the first intubation that widened the stenosis. This decision was further supported the second time by the histopathology, which was consistent with an inflammatory process.

One of the risks of any type of dilation is bleeding into the respiratory system, which, when severe enough, may directly obstruct the airways and become life-threatening. To prevent this complication herein, a small endotracheal tube was first inserted caudal to the stenosis, via endoscopic guidance, and then sufficiently inflated to prevent bleeding into the lungs. Once the airways were secured, a second endotracheal tube was inserted over the small one and positioned at the stenosis site. The balloon was then inflated repeatedly, each time to a larger diameter. The pressure used to inflate the balloon sufficiently was evaluated subjectively, while the mucosa was carefully inspected via the bronchoscope for any damage. Since the procedure was performed using the cuff of a tracheal tube, it was non-obstructive, allowing it to be left in place for a relatively long time, in order to achieve adequate dilation of the stenosis.

Balloon dilation may be performed under fluoroscopic or endoscopic guidance (14,15). Both tracheoscopy and fluoroscopy require specialized equipment and experienced staff. The disadvantage of fluoroscopy is the exposure of the animal and staff to radiation, and its unavailability in many small animal clinics.

In the present case, the balloon dilation was repeated with an interval of 11 mo between treatments. This is a long interval and was acceptable by the owner and veterinarians, and thus should be considered as a treatment option for dogs with tracheal stenosis. The procedure is relatively easy, cost-effective, and quick (compared with resection and anastomosis), resulting in a shorter anesthesia time and decreased risks for anesthetic complication. It provided immediate respiratory relief with no complications, and was performed on an outpatient basis. The procedure was considered successful considering the long intervals between the procedures; although the final outcome was not favorable.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates that when resection and anastomosis or stents cannot be used due to financial constraints, technical difficulties, or the animal’s condition, the use of endotracheal tube balloon should be considered as a palliative treatment for segmental tracheal stenosis. The technique described herein was successful, with no complications, and minimized the risk for respiratory system bleeding. It is relatively easy to perform, inexpensive, and provides an effective alternative to other methods. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Alderson B, Senior JM, Dugdale AH. Tracheal necrosis following tracheal intubation in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:754–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pink JJ. Intramural tracheal haematoma causing acute respiratory obstruction in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2006.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ettinger SJ, Kantrowitz B. Diseases of the trachea. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 6th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1222–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson WA. Diseases of the trachea and bronchi. In: Slatter D, editor. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders; 2002. pp. 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayse ML, Greenheck J, Friedman M, et al. Successful bronchoscopic balloon dilation of nonmalignant tracheobronchial obstruction without fluoroscopy. Chest. 2004;126:634–637. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingland RB, Layton CI, Kennedy GA, et al. A comparison of simple continuous versus simple interrupted suture patterns for tracheal anastomosis after large-segment tracheal resection in dogs. Vet Surg. 1995;24:320–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1995.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culp WT, Weisse C, Cole SG, et al. Intraluminal tracheal stenting for treatment of tracheal narrowing in three cats. Vet Surg. 2007;36:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2006.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couraud L, Jougon JB, Velly JF. Surgical treatment of nontumoral stenoses of the upper airway. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:250–260. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00464-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CD, Grillo HC, Wain JC, et al. Anastomotic complications after tracheal resection: Prognostic factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stepnik MW, Mehl ML, Hardie EM, et al. Outcome of permanent tracheostomy for treatment of upper airway obstruction in cats: 21 cases (1990–2007) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;234:638–643. doi: 10.2460/javma.234.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Han HJ, Yun HY, et al. The safety and efficacy of a new self-expandable intratracheal nitinol stent for the tracheal collapse in dogs. J Vet Sci. 2008;9:91–93. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomori H, Horio H, Suemasu K. Bougienage and balloon dilation using a conventional tracheal tube for tracheobronchial stenosis before stent placement. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:587–591. doi: 10.1007/s004640000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leib MS, Dinnel H, Ward DL, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation of benign esophageal strictures in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:547–552. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2001)015<0547:ebdobe>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berent AC, Weisse C, Todd K, et al. Use of a balloon-expandable metallic stent for treatment of nasopharyngeal stenosis in dogs and cats: Six cases (2005–2007) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:1432–1440. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.9.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen MD, Weber TR, Rao CC. Balloon dilatation of tracheal and bronchial stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:477–478. doi: 10.2214/ajr.142.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]