Pompe disease, also known as Glycogen Storage Disease type II (GSD II), is a rare autosomal recessive disorder, due to α-glucosidase A (GAA) deficiency. This was the first disease identified as a lysosomal storage disorder in 1963 (1) and is characterized by a glycogen accumulation in multiple tissues with a predilection of skeletal muscle and heart. Depending on age of onset, two different clinical forms have been described: infantile and late-onset. Infantile Onset Pompe Disease (IOPD) is associated with a virtual absence of GAA activity (< 1% than normal values) and characterized by severe and rapidly progressive muscle weakness, hypotonia, feeding and respiratory difficulties, severe cardiac hypertrophy often leading to a premature death within the first 2 years of life. Late-onset Pompe Disease (LOPD) is a slowly progressive form, presenting after the first year of age with a juvenile or adult onset. The clinical picture is usually characterized by progressive proximal (highly recurrent limb-girdle distribution) and axial muscle weakness, and respiratory muscle impairment, mainly diaphragmatic. These patients definitely have a better prognosis with a median survival, since diagnosis, of 27 years and a median age of death at 55 years, usually because of respiratory failure and infections (2).

In 2006, the Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT) for Pompe disease has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and by European Medicine Agency. The utilization of ERT has considerably changed the natural history of IOPD improving motor and respiratory function as well as survival. In LOPD, the efficacy of ERT has been demonstrated but with less prominent efficacy when compared to the infantile cases. In fact, it has been shown that ERT may improve or stabilize motor performances and respiratory function in at least 2/3 of treated patients (3, 4). Some studies reported that an early start of therapy may maximize ERT efficacy, suggesting that, in LOPD, an earlier diagnosis has to become the key point in patients' management (5).

In a recent paper, Kishnani et al, using data from the International Pompe Registry, calculated the time interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis in different categories of Pompe patients. Among those patients, the group with onset > 12 months and < 12 years had the longest diagnostic gap: 12.6 years. Similar data are present in other reports from different ethnic groups suggesting that a delayed diagnosis will make more difficult to achieve efficient therapeutic responses (6).

Several clues have been suggested to explain why LOPD diagnosis is difficult: a) rarity of the disorder, b) wide clinical spectrum, c) overlap of signs and symptoms with many other neuromuscular disorders, d) variable diagnostic approach in different countries, e) insufficient awareness of Pompe clinical manifestations, f) difficulties in completing the diagnostic itinerary.

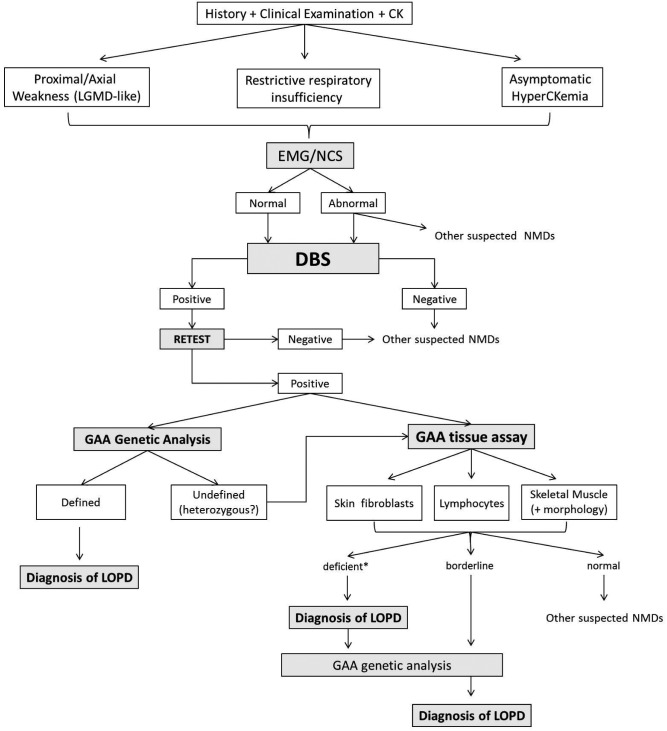

The need for an earlier detection of LOPD cases brought to the development of more rapid diagnostic tools as, for example, the Dried Blood Spot test (DBS) used to investigate, either by fluorometric or by tandem mass spectrometry, the GAA activity. In recent years, some algorithms have been reported (7-10) but on the light of recent diagnostic strategies, it has been suggested to tentatively propose a newly modified algorithm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

LOPD diagnostic algorithm.

(LOPD) Late-Onset Pompe Disease; (LGMD) Limb-Girdle Muscle Dystrophy; (EMG/NCS) electromyography and nerve conduction studies; (NMDs) neuromuscular disorders; (DBS) dried blood spot; (GAA) α-glucosidase A; *GAA activity <30%, borderline 30-40%.

An accurate clinical history is the first step for the diagnosis; patients with LOPD may complain of difficulties in climbing stairs or rising from a chair, excessive fatigue, back pain, exercise intolerance and myalgias. Respiratory symptoms may also represent the onset in some cases: dyspnoea, obstructive sleep apnoea, recurrent pneumonias, morning headache and excessive daytime sleepiness have often been reported (8, 11).

Neurological examination may document weakness of axial and proximal muscles with a limb-girdle distribution that predominantly affects the pelvic girdle. Occasionally, there may be a facial muscle weakness, eye-lidptosis and/or dysphagia. General physical examination may reveal skeletal abnormalities such as scoliosis, lumbar hyperlordosis and rigid spine (12). Cardiac involvement is often present in IOPD whereas it is usually absent or very mild in LOPD being characterized by cardiac arrhythmias, ventricular hypertrophy and Wolf-Parkinson- White syndrome. In the last few years, an involvement of other organs has been increasingly reported such as sensorineural hearing impairment, vascular abnormalities with cerebral aneurysms, gastrointestinal involvement with macroglossia, hepatomegaly, diarrhoea and low body mass index (13-15), further expanding LOPD phenotype and clinical variability.

In the majority of patients, first-line laboratory workup shows an elevation of CK, LDH, AST and ALT. HyperCKemia is usually mild (two-five fold control values) and sometimes can be the only manifestation in asymptomatic patients, however normal CK values do not exclude a diagnosis of LOPD.

The algorithm, herein proposed, distinguishes, after clinical history, neurological examination and routine laboratory tests, three different phenotypes that should raise suspicion of LOPD:

patients presenting with proximal/axial weakness, with or without respiratory symptoms;

patients affected by restrictive respiratory insufficiency;

patients with asymptomatic hyperckemia.

Given the low specificity of such clinical presentations, it is useful to perform electrophysiological studies (comprehensive of needle electromyography, motor nerve conduction velocities and, if necessary, single fibre electromyography) as first-line exams to address clinicians among the different neuromuscular disorders.

Electromyography (EMG) may evidence a myopathic pattern with signs of spontaneous activity and myotonic discharges, often recorded in paraspinal muscles, or it can be normal (16).

At this point, the use of DBS to measure the GAA activity in blood samples is a crucial step.

DBS is a simple, rapid, minimally invasive and inexpensive assay utilized to test patients for GSDII detecting GAA activity in whole blood spots dried on filter paper (17). To obtain reliable DBS results, it is necessary to apply a correct procedure avoiding excessive or insufficient amount of spotted blood (18). For this reason, as previously stated by the Pompe Disease Diagnostic Study Group, it is recommended to confirm DBS positive results repeating the test (Retest), whereas a negative result should suggest other neuromuscular disorders (7, 19).

A positive retest must be followed by a confirmatory biochemical assay and/or by a molecular genetic test. In the former option, clinicians should measure GAA activity in, at least, one other tissue sample (skin fibroblasts, skeletal muscle or purified lymphocytes) whereas the latter option will lead directly to GAA sequence analysis.

Measurement of GAA activity in skin fibroblasts is a minimally invasive, reliable and well-established method. The main disadvantages are related to the difficulties to have access to cell culture facilities as well as the long time needed to obtain the culture results (approximately 4-6 weeks) (19).

Another option is to test GAA activity on purified lymphocytes preparations since they do not contain other isoenzyme activities (i.e. maltase-glucoamylase - MGA). This method could sometimes supply false-negative results if contaminating neutrophils are present in the sample.

GAA assay on skeletal muscle implies performing a muscle biopsy that, even though invasive, can also provide morphological informations, useful in evaluating the severity of muscle degeneration. A vacuolar myopathy is the most frequent finding; vacuoles may stain positive for Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) and show abnormally elevated acid phosphatase reactivity. However, in some cases, muscle biopsy can be normal or with nonspecific changes (20).

Tissue GAA assay, either on skin fibroblasts, skeletal muscle or purified lymphocytes, is generally considered normal if GAA activity is over 40% of control values. In such cases, diagnosis of Pompe disease can be excluded and clinicians should think of an alternative neuromuscular disorder. If GAA tissue activity is below 30% of residual activity, the enzyme is usually considered deficient and a diagnosis of LOPD can be assessed (21). When the enzyme activity is between 30% and 40% (considered borderline values), it is reasonable to think that these cases, that could be either unaffected carriers or patients, need GAA gene molecular analysis to ultimately define their clinical condition.

GAA molecular analysis is important to confirm the diagnosis in the above mentioned cases but also for genotype-phenotype correlations, prognostic implication, family carriers identification and genetic counseling.

Some clinicians, after a positive DBS result, may prefer to directly proceed with GAA gene sequencing. This study often yields to the identification of two pathogenic mutations thus confirming the Pompe diagnosis. However, sometimes just one mutation is detected and this result has to be considered not conclusive and leading back to biochemical assays as already described in the diagnostic tree.

In conclusion, we wish that this new diagnostic algorithm will help clinicians to recognize LOPD patients, thus leading to an early start of ERT, when in agreement with the most recent international guidelines (22).

Department of Neurosciences,

Reference Center for Rare Neuromuscular Disorders,

University of Messina, Italy

References

- 1.Hers HG. Alpha-glucosidase deficiency in generalized glycogen storage disease (Pompe's disease) Biochem J. 1963;86:11–16. doi: 10.1042/bj0860011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gungor D, Vries JM, Hop WC, et al. Survival and associated factors in 268 adults with Pompe disease prior to treatment with enzyme replacement therapy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:34–34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ploeg AT, Clemens PR, Corzo D, et al. A randomized study of alglucosidase alpha in late onset Pompe's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1396–1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toscano A, Schoser B. Enzyme replacement therapy in lateonset Pompe disease: a systematic literature review. J Neurol. 2013;260:951–959. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ploeg AT, Barhon R, Carlson L, et al. Open-label extension study following the late onset treatment study (LOTS) of alglucosidase alpha. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishnani PS, Amartino HM, Lindberg C, et al. Pompe Registry Boards of Advisors, authors. Timing of diagnosis of patients with Pompe disease: Data from the Pompe Registry. Am J Genet Part A. 2013 Aug 30; doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) , author. Diagnostic criteria for late-onset (childhood and adult) Pompe disease. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:149–160. doi: 10.1002/mus.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bembi B, Cerini E, Danesino C, et al. Diagnosis of glycogenosis type II. Neurology. 2008;71(Suppl 2):S4–S11. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31818da91e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kishnani PS, Steiner RD, Bali D, et al. Pompe disease diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med. 2006;8:267–288. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000218152.87434.f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barba-Romero MA, Barrot E, Bautista-Lorite J, et al. Clinical guidelines for late-onset Pompe disease. Rev Neurol. 2012;54:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellies U, Lofaso F. Pompe disease: a neuromuscular disease with respiratory muscle involvement. Respir Med. 2009;103:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schüller A, Wenninger S, Strigl-Pill N, et al. Toward deconstructing the phenotype of late-onset Pompe disease. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160:80–88. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musumeci O, Catalano N, Barca E, et al. Auditory system involvement in late onset Pompe disease: a study of 20 Italian patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107:480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacconi S, Bocquet JD, Chanalet S, et al. Abnormalities of cerebral arteries are frequent in patients with late-onset Pompe disease. J Neurol. 2010;257:1730–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravaglia S, Danesino C, Moglia A, et al. Changes in nutritional status and body composition during enzyme replacement therapy in adult onset type II glycogenosis. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:957–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobson-Webb LD, Dearmey S, Kishnani PS. The clinical and electrodiagnostic characteristics of Pompe disease with post-enzyme replacement therapy findings. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:2312–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamoles NA, Niizawa G, Blanco M, et al. Glycogen Storage Disease type II: enzymatic screening in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2004;347:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vissing J, Lukacs Z, Straub V. Diagnosis of Pompe disease Muscle biopsy vs blood-based assays. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:923–927. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winchester B, Bali D, Bodamer OA, et al. Methods for a prompt and reliable laboratory diagnosis of Pompe disease: Report from an international consensus meeting. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laforêt P, Nicolino M, Eymard PB, et al. Juvenile and adult-onset acid maltase deficiency in France: genotype-phenotype correlation. Neurology. 2000;55:1122–1128. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuser AJJ, Verheijen FW, Kroos MA, et al. Glycogenosis type II (acid maltase deficiency) Muscle Nerve. 1995;3:S61–S61. doi: 10.1002/mus.880181414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cupler EJ, Berger KI, Leshner RT, et al. AANEM Consensus Committee on Late-onset Pompe Disease. Consensus treatment recommendations for late-onset Pompe disease. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:319–333. doi: 10.1002/mus.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]