Abstract

Background

Few studies have examined factors associated with the quality of life (QOL) of patients with renal tumors. Illness uncertainty may influence QOL.

Objective

To prospectively examine the influence of uncertainty on general and cancer-specific QOL and distress in patients undergoing watchful waiting (WW) for a renal mass.

Design, setting, and participants

In 2006–2010, 264 patients were enrolled in a prospective WW registry. The decision for WW was based on patient, tumor, and renal function characteristics at the discretion of the urologist and medical oncologist in the context of the physician–patient interaction. Participants had suspected clinical stage T1–T2 disease, were aged ≥18 yr, and spoke and read English. The first 100 patients enrolled in the registry participated in this study.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Patients completed questionnaires on demographics, illness uncertainty (Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale), general QOL (Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form survey), cancer-specific QOL (Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form), and distress (Impact of Events Scale) at enrollment and at 6, 12, and 24 mo. Age, gender, ethnicity, tumor size, estimated glomerular filtration rate, comorbidities, and assessment time point were controlled for in the models.

Results and limitations

Among the sample, 27 patients had biopsies, and 17 patients had proven renal cell carcinoma. Growth rate was an average of 0.02 cm/yr (standard deviation: 0.03). Mean age was 72.5 yr, 55% of the patients were male, and 84% of the patients were Caucasian. Greater illness uncertainty was associated with poorer general QOL scores in the physical domain (p = 0.008); worse cancer-related QOL in physical (p = 0.001), psychosocial (p < 0.001), and medical (p = 0.034) domains; and higher distress (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

This study is among the first to prospectively examine the QOL of patients with renal tumors undergoing WW and the psychosocial factors that influence QOL. Illness uncertainty predicted general QOL, cancer-specific QOL, and distress. These factors could be targeted in psychosocial interventions to improve the QOL of patients on WW.

Keywords: Kidney cancer, Renal cell carcinoma, Quality of life, Prospective study, Illness uncertainty

1. Introduction

Watchful waiting (WW) is increasingly being used for elderly patients or for patients at high surgical risk who have a small renal mass [1–4]. For patients with small renal tumors, competing risks of death from comorbidities may negate any benefit from active intervention for what are mostly indolent tumors [5]. Our knowledge of WW has matured as our understanding of the natural history of small renal cell carcinomas increases and as nephron-sparing and minimally invasive approaches are more frequently applied. In the spectrum of treatment options for small renal masses, WW represents the ultimate noninvasive and nephron-sparing approach. Recent prospective data have shown that age, renal function preservation, and tumor-related criteria (ie, size and pathologic stage) are independent predictors of quality of life (QOL) for patients undergoing surgical intervention for a renal mass [6]. In contrast, there appears to be little or no information on patient-derived outcomes for patients with a renal mass who are undergoing WW.

Few studies have examined factors that may be associated with the QOL of patients with renal tumors. Two factors that may influence the QOL and psychosocial adjustment of patients with renal tumors are illness uncertainty and fear of disease progression. The uncertainty-in-illness theory states that uncertainty increases when patients lack the information or knowledge to understand their condition, their symptoms or outcomes are unpredictable, and resources (eg, social support, medical care, and education) are insufficient to provide patients with a sense of control over their illness [7–9]. Increasing uncertainty results in less problem-oriented coping, more emotion-oriented coping, and poorer psychosocial adjustment [7,8,10]. Illness uncertainty has not been explored in patients with renal tumors.

Recognizing that few or no data were available on QOL measures in this patient population, in 2006 we opened a clinical trial and registry for patients undergoing surveillance for a small renal mass. The purpose of initiating this registry was to prospectively characterize the psychosocial adjustment and QOL of patients who are on WW. The objective of the current study was to examine the influence of illness uncertainty on distress and QOL over a 2-yr period.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

Between 2006 and 2010, patients from urology and genitourinary medical oncology clinics at a large comprehensive cancer center in the United States were recruited to enroll in our registry. Participants had renal tumors and were undergoing WW for suspected clinical stage T1–T2 disease, were aged ≥18 yr, and were able to speak and read English. The first 100 patients enrolled in this registry were the study participants in our current report.

2.2. Procedure

Study participants completed a baseline questionnaire immediately after registry enrollment and follow-up questionnaires at 6, 12, and 24 mo after enrollment. On the basis of patient, tumor, and renal function characteristics, the decision to use WW had been at the discretion of the urologist and medical oncologist in the context of the physician–patient interaction. All patients received information on their tumor, treatment options, and known contemporary data on the natural history of small renal tumors. At 2–3 wk prior to each follow-up period, the research nurse or coordinator called patients to let them know to expect the questionnaire and to ask them about any medical visits or monitoring they might have had elsewhere for their renal tumors. The follow-up questionnaires were then mailed to participants, along with postage-paid return envelopes. This study was approved by the Surveillance Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment in this study.

2.3. Measures

Patients had completed a questionnaire that assessed age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and education. Medical variables such as tumor size were abstracted from the patients’ charts. Renal function was determined with the Modified Diet in Renal Disease equation to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Medical comorbidity was assessed with a 12-item medical checklist developed to assess an established medical comorbidity [11].

The Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS) was used to assess illness uncertainty [12]. The MUIS was designed to measure patients’ perceptions of uncertainty about their symptoms, diagnoses, treatment, prognosis, and relationship with caregivers. The scale has been used with a variety of medical populations [8,12–14]. There are four subscales on the MUIS, each measuring a different type of uncertainty: ambiguity concerning the state of the illness, complexity concerning treatment and the system of care, lack of information concerning diagnosis and severity of illness, and unpredictability of the course of the illness and outcome. We combined these subscale scores into a single total score; this approach has demonstrated reliability and validity [8,12]. Higher scores on MUIS indicate greater illness uncertainty.

QOL was assessed with both the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form survey (SF-36) and the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form (CARES-SF) [15,16]. The SF-36 is a general QOL instrument assessing eight domains: physical functioning, physical impediments to role functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, emotional impediments to role functioning, and mental health. Two summary scores, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) score and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) score, were computed. Higher scores indicate better QOL. The CARES-SF was used to assess cancer-specific QOL [15,17,18]; this instrument has been extensively validated in patients with a variety of cancers [17]. The CARES-SF has five subscales: physical, psychosocial, medical, sexual functioning, and marital. Higher scores indicate poorer QOL.

The tendency to ruminate on thoughts about stressors (intrusive thoughts) and to avoid thoughts or behaviors related to stressors (avoidance behaviors) was measured using the Impact of Event Scale (IES) [19]. The IES assesses intrusion (ie, intrusively experienced ideas, images, or feelings) and avoidance (ie, avoidance of certain ideas, feelings, or situations). The IES total score, which is simply the sum of the two subscale scores, was used in our analyses. Higher scores indicate more intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed at each of the four time points (baseline, 6 mo, 12 mo, and 24 mo). We examined whether illness uncertainty predicted QOL and distress over time using linear mixed model analyses, controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, tumor size, eGFR, number of comorbidities, and assessment time point. Mixed model regression analysis allows for missing data and improves the precision of effect estimates by using all observed data, provided that missingness depends on only observed variables [20]. In cases in which missingness may depend on unobserved outcomes, the mixed model analysis has potentially less bias by controlling for the covariates in the model on which both the missing outcome values and missingness may depend [20]. All tests conducted were two-sided, at a significance level of 0.05. Power calculations determined that a sample size of 85 patients would give us 80% power to detect a correlation coefficient of 0.30 at 5% significance level. STATA statistical software was used for all analyses.

3. Results

From 2006 through 2010, 264 patients were enrolled in the prospective WW registry, the first 100 of whom form the group characterized in this report. At the time of enrollment, the mean age was 72.5 yr (standard deviation [SD]: 9.9; range: 47.8–91.1) (Table 1). Fifty-five percent of the patients were male, and 84% were Caucasian. Mean tumor size based on radiographic image was 2.3 cm (SD: 1.2) at the first assessment, and mean eGFR was 62.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD: 19.2). Tumor growth rate was an average of 0.02 (SD: 0.03). Nearly all tumors were detected incidentally and were asymptomatic.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics of subjects with small renal tumors undergoing watchful waiting (n = 100)

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 72.5 (9.9) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |

| Female | 45 (45.5) |

| Male | 54 (54.5) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Caucasian | 83 (83.8) |

| Hispanic | 7 (7.1) |

| African American | 9 (9.1) |

| Indication for watchful waiting | |

| Age/comorbidities, no. | 88 |

| Patient choice/refusal of active treatment, no. | 12 |

| Biopsy performed, no. | |

| RCC | 17 |

| Benign | 6 |

| Nondiagnostic | 4 |

| Total | 27 |

| Tumor size, cm, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, ml/min per 1.73 m2, mean (SD) | 62.9 (19.2) |

| Comorbidities, no., mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.4) |

SD = standard deviation; RCC = renal cell carcinoma.

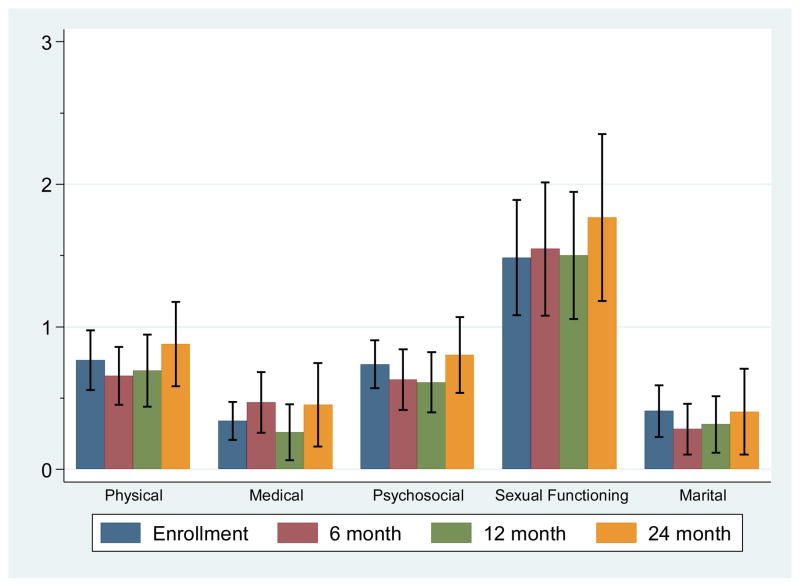

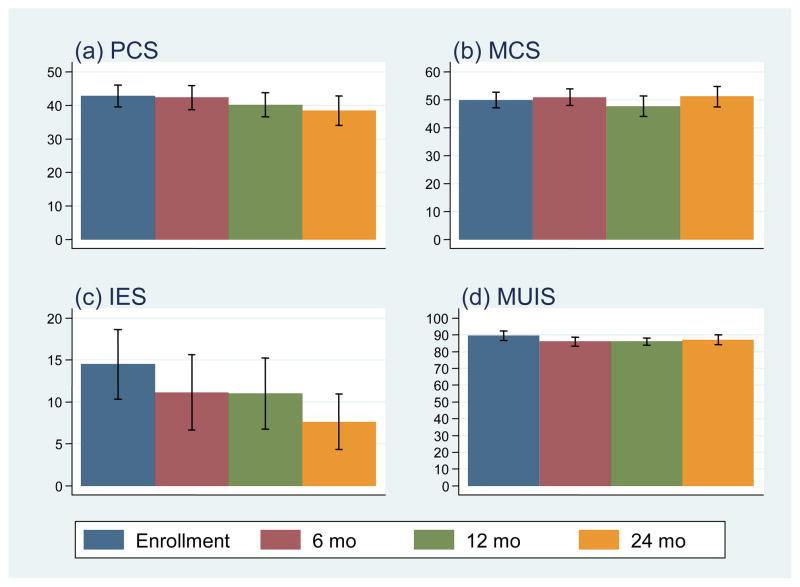

The means and 95% confidence intervals of the scores for CARE-SF and for PCS, MCS, IES, and MUIS at each assessment point are shown in Figure 1 and 2, respectively. We examined whether there were changes over time in general and cancer-specific QOL (SF-36 PCS and MCS; CARES subscales) and intrusive thoughts/avoidance behaviors (IES). Age, gender, ethnicity, tumor size closest to study enrollment, eGFR, and comorbidities were included in the model as covariates. Time significantly predicted PCS QOL scores; scores from baseline to 24 mo were, on average, lower by 4.91 (p = 0.018), indicating that the physical component of QOL decreased over the 24-mo period. Additionally, IES scores were significantly different from baseline to 24 mo, with scores on average 7.13 points lower (p = 0.006), indicating that intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors decreased over the 24-mo period. MCS, CARES and MUIS scores did not significantly change over time (p > 0.10).

Fig. 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form subscale scores over time (n = 100 patients with small renal tumors).

Fig. 2.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for Physical Component Summary (PCS), Mental Component Summary (MCS), Impact of Event Scale (IES), and Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS) scores over time (n = 100 patients with small renal tumors).

We next examined whether illness uncertainty (mean total MUIS score) predicted general QOL (PCS, MCS), cancer-specific QOL (CARES-SF subscales), and intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors (IES) scores. For these analyses, we controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, tumor size, eGFR, number of comorbidities, and assessment time point. Illness uncertainty (MUIS score) predicted the PCS, CARES-SF physical, CARES-SF psychosocial, CARES-SF medical, and IES scores (p ≤ 0.034 for each) (Table 2). Other significant predictors of illness uncertainty scores were assessment time point 24 mo (for PCS and IES scores; p ≤ 0.018 for both), male gender (for CARES-SF physical and psychosocial scores; p ≤ 0.017 for both), eGFR (for CARES-SF physical and psychosocial scores; p ≤ 0.012 for both), age (for CARES-SF sexual functioning score; p < 0.001), tumor size (for CARES-SF sexual functioning score; p < 0.006), number of comorbidities (for CARES-SF marital score; p = 0.024), and Caucasian race (for IES score; p = 0.046).

Table 2.

Significant factors in models using Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale score as a predictor of Physical Component Summary, Mental Component Summary, Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form, and Impact of Event Scale scores for patients with small renal tumors undergoing watchful waiting (n = 100)*

| Survey | Factor | β | 95% LB | 95% UB | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 component summary | |||||

| PCS | MUIS score | −0.28 | −0.48 | −0.07 | 0.008 |

| 24-mo assessment period** | −6.13 | −10.57 | −1.69 | 0.007 | |

| MCS | No significant factors | ||||

| CARES-SF subscale | |||||

| Physical | Male gender | −0.36 | −0.65 | −0.07 | 0.017 |

| eGFR | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.005 | 0.002 | |

| MUIS score | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.001 | |

| Psychosocial | Male gender | −0.33 | −0.59 | −0.07 | 0.015 |

| eGFR | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.002 | 0.012 | |

| MUIS score | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.001 | |

| Medical | MUIS score | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.034 |

| Sexual functioning | Age | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Tumor size | −0.39 | −0.67 | −0.11 | 0.006 | |

| Marital | Number of comorbidities | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.024 |

| IES | Caucasian race | −8.46 | −16.78 | −0.13 | 0.046 |

| MUIS score | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.80 | <0.001 | |

| 24-mo assessment period** | −6.08 | −11.13 | −1.03 | 0.018 | |

SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form survey; CARES-SF = Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form; MCS = Mental Component Summary; PCS = Physical Component Summary; IES = Impact of Event Scale; MUIS = Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; LB = lower boundary; UB = upper boundary.

All models were controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, tumor size, eGFR, comorbidities, and assessment time.

Compared with baseline.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to prospectively examine the QOL of patients with renal tumors on WW and to examine the influence of an important psychosocial factor (illness uncertainty) that influenced QOL in this population. Controlling for sociodemographic factors, tumor size, and comorbidities, we found that illness uncertainty predicted general QOL, cancer-specific QOL, and intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors. Consequently, these factors could be targeted in psychosocial interventions to improve the QOL of patients with renal tumors on WW. Managing uncertainty has been found to be important in men with prostate cancer (PCa) on WW [21,22], and psychosocial interventions focusing on illness uncertainty have been used successfully with PCa patients on WW [23]. Future studies may benefit from similar interventions for patients with renal tumors on WW, as anxiety from the uncertainty may be a reason why patients drop out and why patients desire possibly unnecessary intervention [24,25].

We recently showed, in one of the most comprehensive and largest QOL studies with patients undergoing different types of surgery for a renal mass (open radical, open partial, laparoscopic radical, or laparoscopic partial nephrectomy) who were assessed for 1 yr following surgery, that age had a great effect on how patients experience treatment of their cancer: Younger patients reported significantly less worry but more intrusive thoughts and behaviors [6]. In that study, we also found that all the physical benefits of a minimally invasive approach dissolved by 3 mo, while anxiety and worry over recurrence of cancer remained prominent 1 yr after surgery. Some limitations of our current study should be noted. First, this study was conducted at a specialized cancer center, and our cohort may have differed from patients treated in community hospitals or other settings. Also, the sample was mostly non-Hispanic white (84%), so the results may not be generalizable to other racial or ethnic groups. We also do not know whether differences in QOL would emerge >2 yr after WW was begun.

The patients in this sample had an average age of 72.5 yr. Although we controlled for age in the analyses, it is possible that other factors may be different in elderly patients than younger persons. Future studies should consider systematically comparing older and younger patients with renal tumors to examine age-related differences.

Additional limitations included the fact that there was no structured or standardized counseling or advice plan for discussing management approaches. Also, Charlson and American Society of Anesthesiologists scores were not documented, although we did capture major comorbidities similar to a Charlson score. Most patients did not undergo biopsy. While patients were counseled that they likely had a malignancy, knowledge of tumor histology may have affected the QOL results.

It is possible that participating in research and completing questionnaires at multiple time points could change patients’ behavior. However, behavior is known to be quite challenging to change, and change typically requires significant psychosocial or behavioral intervention in addition to assessments. In this study, there was no type of psychosocial or behavioral intervention; it was solely a longitudinal assessment study. We followed standardized and well-accepted procedures to minimize the effect of this and other biases [26,27]. For example, a neutral research assistant rather than the study participants’ physician or study researchers collected the questionnaire data, thus minimizing the likelihood of the participants completing the questionnaires in a certain way to please the physician or researcher.

A strength of our design is that we statistically controlled for the QOL at baseline. All prospective studies that collect patient-reported outcome data have this inherent potential bias; however, it is generally believed to be very minimal. It is important to note that all the measures used in this study have been found to be both reliable and valid and have been used extensively in studies assessing the psychosocial adjustment and QOL of individuals with cancer and other medical conditions. An important aspect of our study is that it included both general and cancer-specific QOL, as well as measures of distress (ie, intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors).

5. Conclusions

We prospectively examined the QOL of patients with renal tumors undergoing WW and the psychosocial factors that influence QOL. Illness uncertainty predicted general QOL, cancer-specific QOL, and intrusive thoughts and avoidance behaviors. Our study found illness uncertainty that can be targeted in psychosocial interventions to improve the QOL over time of patients undergoing WW for renal tumors.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672 and by the National Kidney Foundation Bristol Myers Squibb Young Investigator grant (SFM).

Acknowledgment statement: Elizabeth Hess reviewed the manuscript for grammatical editing. We thank Mary McCabe, data coordinator, for database management. We are also indebted to the patients who volunteered for this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Patricia A. Parker had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Parker, Alba, Matin, Wood.

Acquisition of data: Karam, Tannir, Jonasch, Wood.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Fellman, Urbauer, Li, Parker, Matin.

Drafting of the manuscript: Parker, Matin.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Parker, Alba, Fellman, Urbauer, Li, Karam, Tannir, Jonasch, Wood, Matin.

Statistical analysis: Fellman, Urbauer, Li.

Obtaining funding: Matin.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Matin.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Patricia A. Parker certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bosniak MA. Observation of small incidentally detected renal masses. Semin Urol Oncol. 1995;13:267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassouf W, Aprikian AG, Laplante M, Tanguay S. Natural history of renal masses followed expectantly. J Urol. 2004;171:111–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000102409.69570.f5. discussion 113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volpe A, Panzarella T, Rendon RA, Haider MA, Kondylis FI, Jewett MA. The natural history of incidentally detected small renal masses. Cancer. 2004;100:738–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crispen PL, Viterbo R, Boorjian SA, Greenberg RE, Chen DYT, Uzzo RG. Natural history, growth kinetics, and outcomes of untreated clinically localized renal tumors under active surveillance. Cancer. 2009;115:2844–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crispen PL, Viterbo R, Fox EB, Greenberg RE, Chen DYT, Uzzo RG. Delayed intervention of sporadic renal masses undergoing active surveillance. Cancer. 2008;112:1051–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker PA, Swartz R, Fellman B, et al. Comprehensive assessment of quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in patients with renal tumors undergoing open, laparoscopic and nephron sparing surgery. J Urol. 2012;187:822–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishel MH, Padilla G, Grant M, Sorenson DS. Uncertainty in illness theory: a replication of the mediating effects of mastery and coping. Nurs Res. 1991;40:236–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishel MH, Hostetter T, King B, Graham V. Predictors of psychosocial adjustment in patients newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7:291–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishel MH, Braden CJ. Finding meaning: antecedents of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1988;37:98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazer MW, Bailey DE, Jr, Chipman J, et al. Uncertainty and perception of danger among patients undergoing treatment for prostate cancer. Br J Urol. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11439.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield S, Apolone G, McNeil BJ, Cleary PD. The importance of co-existent disease in the occurrence of postoperative complications and one-year recovery in patients undergoing total hip replacement: comorbidity and outcomes after hip replacement. Med Care. 1993;31:141–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishel MH. The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res. 1981;30:258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishel MH. Parents’ perception of uncertainty concerning their hospitalized child. Nurs Res. 1983;32:324–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishel MH. Adjusting the fit: development of uncertainty scales for specific clinical populations. West J Nurs Res. 1983;5:355–70. doi: 10.1177/019394598300500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schag CA, Ganz PA, Heinrich RL. Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System–Short Form (CARES-SF): a cancer specific rehabilitation and quality of life instrument. Cancer. 1991;68:1406–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6<1406::aid-cncr2820680638>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre Hospitals; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schag CA, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) manual. Los Angeles, CA: CARES Consultants; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz PA, Schag CA, Lee JJ, Sim MS. The CARES: a generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00435432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey DE, Jr, Wallace M, Mishel MH. Watching, waiting and uncertainty in prostate cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:734–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliffe JL, Davison BJ, Pickles T, Mroz L. The self-management of uncertainty among men undertaking active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Qualitative Health Res. 2009;19:432–43. doi: 10.1177/1049732309332692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey DE, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Mohler J. Uncertainty intervention for watchful waiting in prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:339–46. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jewett MA, Mattar K, Basiuk J, et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses: progression patterns of early stage kidney cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178:826–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose M, Bezjak A. Logistics of collecting patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical practice: an overview and practical examples. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:125–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, Jenkinson C, Carr AJ. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ. 2010;340:c186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]