Abstract

For years, investigators have sought to prove that myelin antigens are the primary targets of autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis (MS). Recent experiments have begun to challenge this assumption, particularly when studying the neurodegenerative phase of MS. T-lymphocyte responses to myelin antigens have been extensively studied, and are likely early contributors to the pathogenesis of MS. Antibodies to myelin antigens have a much more inconstant association with the pathogenesis of MS. Recent studies indicate that antibodies to non-myelin antigens such as neurofilaments, neurofascin, RNA binding proteins and potassium channels may contribute to the pathogenesis of MS. The purpose of this review is to analyze recent studies that examine the role that autoantibodies to non-myelin antigens might play in the pathogenesis of MS.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Neurodegeneration, Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP A1), Autoimmunity, Spastic paraparesis, RNA binding protein, Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)

Background

MS is the most common immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in humans [1,2]. There are approximately 2 million MS cases worldwide and like most autoimmune diseases, MS disproportionally affects middle-aged women [1,2]. Initially, two-thirds of patients develop relapsing remitting MS (RRMS), in which neurologic symptoms occur followed by partial or complete recovery [1–4]. Following RRMS, a majority of patients (up to 90% within 25 years) develop secondary progressive MS (SPMS), manifested by neurological deterioration without relapses [1–5]. Approximately 15% of MS patients are diagnosed with primary progressive MS (PPMS), in which neurological symptoms progress from onset without relapses [1–4]. Therefore, the majority of patients develop progressive forms of MS during their lifetime. Symptoms of progressive forms of MS commonly involve the long tracts of the CNS, and include spastic paraparesis, sensory dysfunction, ataxia and urinary dysfunction [6,7].

Pathologically, the most obvious abnormalities of the CNS are ‘MS plaques’, areas of demyelination of white matter in a milieu of inflammatory cells (T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells) [8]. A series of elegant studies also describe plaques involving gray matter; axonal and neuronal injury (known as neurodegeneration); as well as changes in inflammatory profiles related to the type of MS [4,5,9–20]. Since demyelination was considered the hallmark of MS, a plethora of studies examined the potential role that immune response to myelin proteins play in the pathogenesis of MS. The robust T-lymphocyte response in the plaque, the discovery of the T-cell receptor and it specificity related to HLA of its target cell; and the use of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE, a predominantly T-cell mediated model of MS), led to the study of T-cell responses to myelin targets as important hypotheses describing the pathogenesis of MS [21–37]. Many studies showed that T-lymphocytes from MS patients preferentially target myelin peptides derived from myelin basis protein (MBP), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), proteolipid protein (PLP) and myelin oligodendrocytic basic glycoprotein (MOBP) [28,38–44]. In addition, EAE is induced by many of these same myelin peptides or by adoptive transfer of T-cells isolated from animals immunized by myelin peptides [45,46]. Further, studies showed that Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T-cell responses were definite contributors to the pathogenesis of EAE and likely important in the pathogenesis of MS [36,37,47]. However, some of these observations were tempered by the realization that healthy controls also develop T-cell responses to myelin peptides. More recently, CD8+ T-cells have also been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of EAE and MS [48–51].

In addition to cellular immune response, humoral responses to myelin protein antigens were extensively studied. Many of these studies led to conflicting results. Alternatively, experiments examined the role of both T-cell and antibody responses to non-myelin targets as contributors to pathogenesis of MS. Examples of important T-cell responses to non-myelin antigens include osteopontin, αB crystalline and contactin-2 [52–55]. Interestingly, antibody responses to non-myelin antigens such as neurofilaments, neurofascin, RNA binding proteins and potassium channels have also been recently implicated in the pathogenesis of MS, which will be the primary focus of this review [2,7,56–62].

Antibodies to Myelin Antigens

For more than 35 years, scientists have been studying whether antibodies to myelin protein antigens contribute to the diagnosis and pathogenesis of MS (Table 1). Antibodies from both serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were examined. Lisak et al., used immunofluorescence of serum IgG applied to monkey or guinea pig spinal cord sections on slides [63]. This group examined 41 MS patients. Controls included patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) and healthy controls (HC). All groups were found to immunoreact with myelin contained within spinal cord sections [63]. Patients with ALS, MS and GBS had greater titers than HCs, with ALS showing the highest titers [63]. Next, using radioimmunoassays (RIAs), a series of studies examined whether IgG isolated from the CSF of MS patients was specific for myelin basic protein (MBP) [64–66]. Although some studies showed differences between MS patients and patient without neurologic disease, the majority could not differentiate MS patients from patients with other neurologic diseases such as SSPE, GBS, ALS, or neurosyphilis [64–66]. With the advent of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and MOG as a target antigen, researchers began to use ELISA to study immunoreactivity to both MBP and MOG. One study showed that CSF from only 7/30 patients immunoreacted with MOG compared to 3/30 patients with other neurologic disease (OND) [67]. Using serial dilutions of serum and CSF, Reindl et al., showed little difference in immunoreactivity to MOG or MBP when comparing MS patients (n=132) with patients with other inflammatory neurological diseases (OIND) (n=32), (OND) (n=30) or rheumatoid arthritis patients (n=10) [68]. The highest percentage of positive antibodies titers to MOG and MBP were in patients with OIND [68]. Although there were some differences between the study groups, none were consistently in favor of MS [68]. Karni et al., used antibodies isolated from paired plasma and CSF samples of patients with MS, OND and HC [69]. Interestingly, the OND group included both inflammatory and neurodegenerative neurological diseases. In CSF, antibodies to MOG and MBP were elevated in both MS and OND compared to HC. In serum, titers were slightly elevated in MS patients compared to OND, but the frequency of positive response was similar between the groups [69]. This led the authors to conclude that anti-MOG antibodies were not specific for MS [69].

Table 1.

A sampling of antibody studies in MS.

| I. Myelin: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | MS/CIS | Controls | Serum | CSF | Antigen/technology | Primary results |

| Lisak et al.,1975 [63] | 41 | 5 ALS; 16 OND (GBS, SSPE); 22 HC |

IgG | ND | IMF of myelin in monkey or guinea pig spinal cord. |

All groups reacted with higher titers than HC. ALS showed greatest immunoreactivity. |

| Panitch et al., 1980 [64] | 48 | 30 SSPE; 12 OND |

ND | IgG | MBP. Solid phase RIA. |

SSPE>MS>OND |

| Gorny et al., 1983 [65] | 18 | 13 SSPE; 22 OND; 7 neurotic | ND | IgG | MBP. RIA. |

SSPE (61%)>MS (44%)>OND (31%) |

| Wajgt and Gorny, 1983 [66] | 40 | 40 neurotic | ND | IgG | MBP, MAG. RIA. |

MS positive: MBP (35%), MAG (70%), both (33%). Neurotic (0%) |

| Xiao et al., 1991 [67] | 30 | 30 OND; 30 HA | ND | IgG | MOG. ELISA. |

MS (23%); OND (10%), HA (3%) |

| Reindl et al., 1999 [68] | 130 | 32 OIND; 30 ONND; 10 RA |

IgG | IgG | MBP. MOG. WB, ELISA. |

No differences between groups by ELISA. WB highest in OIND; differences between groups not in favor of MS. |

| Karni et al., 1999 [69] | 33 sera 31 CSF |

Sera: 31 OND; 28 HC. CSF: 28 OND; 31 HC |

IgG, IgM, IgA |

IgG, IgM, IgA | MBP, MOG. ELISA. |

CSF: Abs to MOG, MBP elevated in MS & OND vs. HC. Frequency higher to MOG in MS & OND (not to MBP). Sera: titers elevated in MS vs. ONDs & HC, but frequency similar between groups. |

| Berger et al., 2003 [70] | 103 CIS OCB (+) | None | IgM | ND | MBP, MOG. WB. |

MOG/MBP: +/+ (21%); −/− (38%); +/− (41%). 95% of MOG/MBP +/+ had relapse & predicted RRMS (≈100%) |

| Lampasona et al., 2004 [73] | 87 | 12 EC,47 HC | IgG, IgM | ND | MOG. WB, RBD. |

No difference between groups. |

| Mantegazza et al., 2004 [74] | 262 (175 RR; 44 SP; 43 PP) |

131 OND 307 HC |

IgG | IgG | MOG (extracellular domain). ELISA. WB. |

CSF: no differences. Sera: MS (14%); OND (14%); HC (6%). Not specific for MS. CPMS: titer correlates with severity |

| Lim et al., 2005 [78] | 47 CIS | None | IgG, IgM | ND | MBP. MOG. WB. |

Abs to MBP/MOG did not predict CDMS |

| Lalive et al., 2006 [80] | 92 (35 RR; 33 SP; 24 PP). 36 CIS |

37 HC | IgG | ND | MOG (native in transfected human cells) |

Significant differences between CIS, RR, SP vs. HC, but not PP. |

| Rauer et al., 2006 [75] | 45 CIS | 56 HC | IgM | ND | MBP, MOG. WB. |

No increase risk for CDMS. Ab (+) patients developed earlier relapses. |

| Khalil et al., 2006 [77] | 28 | 20 HC | IgG, IgM, IgA |

ND | MOG. ELISA. |

IgM not significant. IgG and IgA significant. High degree of value overlaps between groups. |

| Kuhle et al., 2007 [79] | 462 CIS | None | IgG, IgM | ND | MBP, MOG. WB. |

Risk of CDMS not influenced by any combination of positive Abs. |

| Menge et al., 2007 [81] | 37 (17 RR; 10 SP; 10 PP) |

13 HC | IgG | ND | rhMOG ELISA |

No differences |

| Greeve et al., 2007 [71] | 31 CIS | None | IgM | ND | MBP, MOG. WB. |

MOG/MBP: +/+ & +/− greater risk of CDMS than −/− |

| Tomassini et al., 2007 [72] | 51 CIS | None | IgG, IgM | ND | MBP, MOG. WB. |

Any positive Ab predicted CDMS by Poser criteria, not McDonald criteria. |

| Pittock et al., 2007 [82] | 72 (12 pI; 43 pII, 17 pIII) |

None | IgG, IgM | ND | MOG ELISA. WB. |

No association with CDMS. |

| Wang et al., 2008 [76] | 126 | 252 HC | IgG, IgM | ND | MOG. EBNA. ELISA. |

2X increase of MS, but no association after adjustment for EBNA Abs. |

| Belogurov et al., 2008 [83] | 26 | 22 OND, 11 HC |

IgG | ND | MBP. MOG. ELISA. |

MOG & MBP: Significant differences vs. HC, not OND. Only Abs to MBP 43–68, 146–170 distinguished MS from OND. |

| Hedegaard et al., 2009 [84] | 17 | 17 HC | IgG | ND | MBP microsphere. | No differences. |

| Chan et al., 2010 [85] | 25 patients prior to CIS |

21 HC | IgG, IgM | ND | Linear MBP. Linear and native MOG. |

No association with CIS development. |

| Tewarie, et al., 2012 [86] | 77 (37 RR; 27 SP, 13 PP) |

26 OND; 9 OIND | IgG | IgG | Myelin | No differences |

| II. Non-myelin: | ||||||

| Rawes et al., 1997 [88] | 20 | 17 OND, 13 HC | IgG | IgG | Axolemma enriched fraction (AEF). ELISA |

Serum & CSF: significant differences in mean absorbance in MS compared to OND, HC. No correlation with myelin Ag |

| Sadatipour et al., 1998 [89] | 70 (33 RR; 21 SP, 16 PP) |

41 OND, 38 HC | Poly-valent Ig |

ND | Gangliosides GM1, GM3, GD1a, GD1b, GD3 |

Significant differences in GM3: PP, SP compared to RRMS, OND, and HC |

| Silber et al., 2002 [56] | 67 (39 RR;18 SP; 10 PP) |

40 OND; 21 OIND; 12 HC |

IgG | IgG | NF-L, NF-H, tubulin | Anti-NF-L antibodies significantly elevated in PPMS and SPMS compared to controls; correlated with EDSS |

| Eikelenblom et al., 2003 [57] | 51 MS: 21 RR; 20 SP; 10 PP |

None | ND | IgG | NF-L, NF-H | Anti-NF-L IgG index correlated with parenchymal fraction, T2 lesion load, T1 lesion load & ventricular fraction |

| Lily et al., 2004 [94] | 58 (35 RR (9 benign); 23 SP |

12 HC 16 OND |

IgG, IgM | ND | SK-N-SH neurons Oligodendrocyte precursor cell lines |

Only SK-N-SH cells showed differential response between SP (75%) and RR (25%). No differences in OPCs. |

| Mathey et al., 2007 [58] | 26 (13 RR; 4 possible, 9 CPMS) |

17 OIND 21 HC blood donors |

IgG | ND | Neurofascin NF186 (axonal) NF155 (oligodendrocyte) |

Highest titers: CPMS vs OIND to NF 155, which cross-reacts with NF 186. |

| Lee et al., 2011 [7] | 37 (18 RR; 10 SP; 9 PP) |

8 HC, 5 AD | IgG | IgG | hnRNP A1–M9 (AA 293–304) WB. |

Sera: MS (100% (+)); HC (0%); AD (0%). Single positive MS OCB in CSF. |

| Srivastava et al., 2012 [59] | 397 | 329 OND; 59 HC | IgG | ND | KIR4.1 ELISA |

KIR4.1 (AA 83–120): MS (47%); OND (0.9%), HC (0%). |

| III. Myelin & non-myelin: | ||||||

| Kanter et al., 2006 [128] | 16 (8 RR; 8 SP) | 11 OND | ND | IgG, IgM | Lipid microarray | MS vs OND: sulfatide. 3β-hydroxy-5α-cholestan-15-one, oxidized phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidyl ethanolmine, lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine, sphingo-myelin, lipopolysaccharide, asialo-GM-1. SPMS vs OND: GM1, asialo-GM1. |

| Ousman et al., 2007 [54] | 12 RR | 12 OND | ND | IgG, IgM | ‘Myelin’ antigen array | αB crystallin 21–40; golli-MBP iso J37; MBP; PLP, HSP, amyloid beta 1–12 |

| Quintana et al., 2008 [130] | 14 RR vs 10 HC. 13 PP vs 12 HC. 37 RR vs 30 SP. |

See MS/CIS column (left) |

IgG, IgM | ND | Tripartite antigen array of CNS, HSP and lipid antigens |

RR vs HC: CNS & myelin Ags, GFAP, lactocerebroside, beta amyloid. PP vs HC: myelin Ags, beta amyloid, NF-68, superoxide dismutase. PP, SP vs. RR: lower titers to HSP. |

| Derfuss et al., 2009 [55] | sera: 56. CSF: 24 (16 CDMS, 8 probable MS) |

sera: 45 OIND; 12 OND; 40 HCCSF: 25 OIND; 35 OND |

IgG | IgG | Contactin-2 (human)/ TAG-1 (rat) |

Sera: no differences between groups. CSF: significance between MS & OIND but not OND. T-cells to TAG-1 with anti-MOG abs required to induce disease. |

AA: Aminoacid; Abs: Antibodies; Ag: Antigen; AD: Alzheimer ‘s disease; ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CIS: Clinically isolated syndrome; CDMS: Clinically definite multiple sclerosis; CNS: Central nervous system; CPMS: Chronic progressive multiple sclerosis; CSF: Cerebrospinal fuid; EBNA: Epstein Barr nuclear antigen; EC: Encephalitis; ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein; GBS: Guillain Barre Syndrome; HA: Headache; HC: Healthy controls; hnRNP A1: Heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear protein A1; HSP: Heat shock proteins; IMF: immunofluorescence; iso: isoform; MAG: Myelin associated glycoprotein; MBP: Myelin basic protein; MOG: Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MS: Multiple sclerosis; ND: Not done; NF-L: Neuroflament light chain; NF-H: Neuroflament heavy chain; NF-68: Neuroflament 68; NF 155: Neurofascin 155 kDa; NF 186: Neurofascin 186 kDa; OCB: Oligoclonal bands; OIND: Other inflammatory neurologic disease; OND: Other neurologic disease; ONND: Other non-inflammatory neurologic disease; p: pattern; PP: Primary progressive MS; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; RBD: Radio-binding assay; rh – recombinant, human; RIA: Radioimmunoassay; RRMS: Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; SP: Secondary progressive MS; SSPE: Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis; TAG-1: Transiently expressed axonal glycoprotein 1; WB: Western blot

In 2003, Berger et al., reported the results of a study examining whether serum IgM antibodies to MOG and MBP in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) might predict conversion to clinically definite MS (CDMS) [70]. Using Western blots, this study showed that CIS patients with antibodies to both MBP and MOG were more likely to develop an MS relapse, have a shorter time period to relapse and a dramatically increased risk for developing CDMS (approaching 100%) compared to CIS patients who were negative for both antigens [70]. Patients who were positive for MOG but negative for MBP had an intermediate risk for developing a relapse and CDMS [70]. These data were replicated in a smaller study (n=31) [71]. Interestingly, a separate study showed the risk of conversion from CIS to CDMS correlated with the Poser diagnostic criteria for MS, but not the more recently developed McDonald criteria [72]. None of these studies analyzed IgM responses to HCs. When HCs were analyzed, associations between anti-myelin antibodies and MS were more difficult to prove. For example, several studies reported no differences in serum anti-MOG IgG or IgM levels in MS patients compared to patients with OND or HC [73–75]. In one study, there was a two-fold increase in risk of MS in anti-MOG positive patients, however, the association dissolved after adjustment to antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus [76]. In a separate study, when HCs were included in the study of MS (not CIS), there was no significance between groups when analyzing anti-MOG IgM [77]. Data were significant when studying IgG and IgA antibodies to MOG, however the overlap in raw values in the MS and control groups were so close as to question their utility in defining the disease state [77]. In 2005, a small studied (47 CIS patients) showed no correlation between anti-MOG or anti-MBP antibodies and the development of CDMS (by either Poser or McDonald criteria) [78]. In 2007, Kuhle and Pohl et al. used MOG and MBP Western blots to analyze serum IgG and IgM anti-MOG and anti-MBP antibodies in 462 CIS patients [79]. Their data showed no association between antibodies to either MOG or MBP and the risk for CIS patients developing CDMS [79]. Several studies continued to analyze the contribution of anti-MOG and anti-MBP antibodies to the diagnosis and pathogenesis of MS. Using a cell-based assay in which conformational epitopes can be detected, Lalive et al, showed differences in anti-MOG antibodies in RRMS, and SPMS compared to HC, but not PPMS [80]. However, using the same assay, Menge et al., showed that there was no difference in anti-MOG antibodies in MS patients compared to HCs [81]. In addition, in 72 MS patients who underwent brain biopsy of variable pathogenic MS subtypes (12 pattern 1, 43 pattern II, 17 pattern III) none showed a correlation between anti-MOG status (by either ELISA or Western blot) and conversion to CDMS [82]. Subsequently, multiple studies (using a number of different technologies) have shown little or no differences in anti-MOG and anti-MBP antibodies between neither MS and control patients nor associations with the development of CIS or CDMS [83–86]. Taken together, these data suggest that in humans, anti-myelin antibodies cannot be consistently utilized to diagnose MS, and are unlikely contributors to the pathogenesis of MS. These conclusions are further supported by Owens et al., who examined recombinant monoclonal antibodies derived from the light-chain variable region sequences of B- and plasma cells isolated from the CSF of MS patients for immunoreactivity to MBP, PLP and MOG [87]. Notably, none of the recombinant antibodies reacted with these three common myelin antigens [87]. These data suggest that myelin may not be the primary target for a pathogenic antibody response in MS and other CNS antigens, such as to neurons, axons and glia, may be important contributors to the pathogenesis of MS.

Antibodies to Non-myelin Self-antigens

In 1997, Rawes et al., examined the immunoreactivity of MS IgG to axonal plasma membranes, known as the ‘axolemma enriched fraction (AEF) [88] (Table 1). The authors hypothesized that target antigens in the AEF escaped self-tolerance and immune surveillance because of myelin coating of the axons. Following demyelination, cryptic antigens would be available to the acquired immune response for antibodies to develop. They measured immunoreactivity of IgG in the serum and CSF from MS and control patients to the AEF. There was no immunoreactivity in HC. Immunoreactivity (measured by ELISA as mean absorbance) was greater in both the CSF and sera of MS compared to OND. Interestingly, there was no correlation between these values and immunoreactivity to myelin antigens [88].

Gangliosides are predominantly axonal antigens, and are also minor components of the myelin sheath [89]. As early as 1980, studies indicated that MS patients developed antibodies to different gangliosides, however many of these studies were made up of small groups and incompletely controlled [89]. In 1998, Sadatipour et al., reported the results of immunoglobulin immunoreactivity to a series of gangliosides (GM1, GM3, GD1a, GD1b, and GD3) in MS patients (n=70; 33 RRMS, 21 SPMS, 16 PPMS), patients with OND (n=41) and HCs (n=38) [89]. There were significant differences between progressive forms of MS and the other test groups (including RRMS) to a number of the gangliosides, with the anti-GM3 being the most robust response in PPMS and SPMS compared to RRMS, OND and HCs [89].

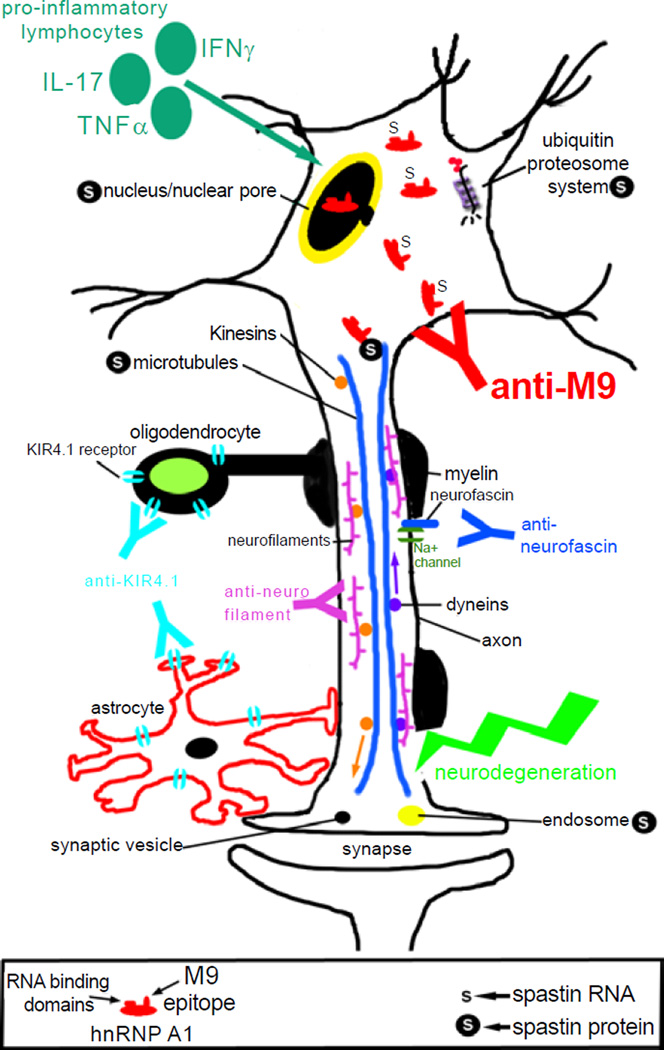

Neurofilaments (NF) are major constituents of the axonal cytoskeleton and play critical roles in axonal radial growth, maintenance of axon caliber and transmission of electrical impulses [56,90]. NF-L (68 kD ‘light’ subunit) is a primary component of the NF core. NF-H (200 kD, ‘heavy’) is located peripherally. Silber et al., showed that intrathecal production of anti-NF-L IgG antibodies were significantly elevated in PPMS and SPMS patients compared to controls (OND, OIND, HC) [56]. In addition, oligoclonal bands were found to immunoreact with NF-L and anti-NF-L antibodies correlated with disability as calculated by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [56]. There were no correlations with antibodies detected in serum [56]. In a related study, Eikelenboom et al., examined potential correlations between anti-NF-L antibodies and cerebral atrophy [57]. The authors found a strong correlation between intrathecal anti-NF-L antibodies (the ‘anti-NF-L index’) and four different MRI markers of cerebral atrophy (parenchymal fraction, T2 lesion load, ventricular fraction and T1 lesion load) [57]. Interestingly, a study of CSF NF-L levels (not antibodies) also correlated with clinical markers of disease progression [91]. Animal studies related to these clinical observations suggest that autoimmunity to neurofilaments contribute to the pathogenesis of MS [60,61,92]. For example, following immunization with NF-L protein in ABH mice, animals developed spastic paraparesis concurrent with spinal cord axonal degeneration [60]. The mice developed a pro-inflammatory T- cell response, and importantly, they also developed antibodies to NF-L and IgG deposits within axons of spinal cord lesions [60]. In contrast to MOG-EAE, this NF-L EAE model showed a greater degree of spastic paraparesis, predominantly dorsal column and gray matter axonal degeneration as well as empty myelin sheaths [61]. Interestingly, like myelin proteins, neuronal proteins including NF-L are phagocytosed by human microglia in vitro and within MS plaques [93]. Taken together, these data indicate that autoimmunity to neurofilaments, and in particular, antibodies to neurofilaments, contribute to the pathogenesis of EAE, and potentially MS [61] (Figure 1). In a separate study, antibodies from the sera of MS patients were tested for immunoreactivity to oligodendrocyte, astrocyte and neuronal cell lines. MS patients showed increased immunoreactivity to all three cell lines compared to controls. However, only in the neuronal cell line (SK-N-SH), was there significant binding using sera from SPMS patients compared to RRMS, benign MS and HCs [94].

Figure 1. Potential contribution of antibodies to neurodegeneration in MS.

Following a pro-inflammatory T-cell response, antibodies to a number of neuronal antigens may contribute to neurodegeneration such as anti-KIR4.1, anti-neuroflament, anti-neurofascin or anti-hnRNP A1-M9 (red). Spastin contains an hnRNP A1 binding site and hnRNP A1 has been shown to bind spastin RNA. Spastin has been shown to contribute to neuronal function at multiple levels including the nucleus/nuclear pore, proteosome, microtubules and endosomes. Anti-M9 antibodies have been shown to alter spastin RNA levels in neurons and may affect spastin function at these sites.

Several groups have used an unbiased proteomics approach to identify putative autoantigens in MS patients [55,58,59,95]. For example, MS IgG was used to probe the glycoprotein fraction of human myelin purified by lectin affinity chromatography [55,58,95]. Proteins immunoreactive with MS IgG were identified by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by mass spectroscopy. These studies identified immunoreactivity to two proteins: neurofascin and contactin-2/TAG-1 (transiently expressed axonal glycoprotein 1, the rat orthologue of contactin-2) [55,58,95]. Immunoreactivity to neurofascin was highest in a modest number of sera from chronic progressive MS patients [58]. MS IgG immunoreacted with two distinct isoforms of neurofascin: neurofascin 155 (an oligodendrocyte specific isoform) and neurofascin 186 (a neuronal form concentrated in axons at nodes of Ranvier) [58]. Application of anti-neurofascin antibodies to hippocampal slice cultures inhibited axonal conduction [58]. Following induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) with MOG-specific T-cells, the addition of anti-neurofascin antibodies worsened clinical disease [58]. Anti-neurofascin antibodies bound to nodes of Ranvier, resulting in complement deposition and axonal injury. Taken together, these data indicate antibodies that target neuronal antigens are pathogenic and contribute to neurodegeneration [58,96] (Figure 1).

Most recently, IgG from MS patients was used in immunoprecipitation reactions of CNS membrane expressed proteins to identify putative autoantigens [59]. Following immunoprecipitation, two-dimensional electrophoresis of the eluent proteins in tandem with Western blot analyses (using MS IgG) and matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry identified the protein KIR4.1, a glial potassium channel [59]. Remarkably, 186/397 (46.9%) of MS patients were immunoreactive for KIR4.1 compared to 3/329 persons with OND (0.9%) and none of the 59 HCs. Importantly, MS antibodies bound glial cells in human brain sections and the immunodominant epitope (AA 83–120) was found to overlap one of two extracellular loops of KIR4.1 (AA 90–114). Infusions of anti-KIR4.1 antibodies with human complement in to the cisterna magna of mice showed loss of KIR4.1 expression and activation of complement [59]. Taken together, these data suggest that the antibodies to the non-myelin antigen KIR4.1 may be a biomarker for and contribute to the pathogenesis of MS [59] (Figure 1).

Similar to the studies above, our laboratory (more than a decade ago) utilized an unbiased proteomics approach to test the hypothesis that antibodies isolated from patients with immune mediated neurological disease would immunoreact with CNS neuronal antigens [97]. We utilized a human neuron preparation taken at autopsy that is used to identify neuronal antigens in paraneoplastic syndromes [97–100]. The model we chose to examine was human T-lymphotrophic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) because it is similar pathologically, immunologically and clinically to progressive forms of MS [2,7,101–103]. Specifically, neuronal proteins isolated from human brain were separated by two-dimensional electrophoresis and transferred to membranes for Western blotting. We isolated IgG from HAM/TSP patients and used it to probe the Western blots. Following isolation and purification of the protein that immunoreacted with HAM/TSP IgG, matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry identified the target protein as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP A1) [97]. Importantly, an HTLV-1-tax monoclonal antibody showed cross-reactivity with human neurons and hnRNP A1, indicative of molecular mimicry between the two proteins [97,102–104]. hnRNP A1 is an RNA binding protein that is overexpressed in large neurons, whose primary function it to transport mature mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [97,102,105,106]. In contrast to HCs, all HAM/TSP patients tested immunoreacted with hnRNP A1 [97]. Te human immunodominant epitope was experimentally determined to be within ‘M9’, the sequence of hnRNP A1 required for its nucleocytoplasmic transport [2,107,108]. In addition, HAM/TSP IgG immunoreacted preferentially with Betz cells, the cells of origin of the corticospinal tract and in HAM/TSP brain in situ IgG localized to neurons and axons of the corticospinal system [97,109]. Importantly, hnRNP A1-specific IgG that was affinity purified from HAM/TSP patients inhibited neuronal firing in an ex vivo patch clamp system [2,97,110]. Taken together, these data suggest that antibodies were biologically active, specific for neuronal systems preferentially damaged and potentially pathogenic in HAM/TSP [2,102,103].

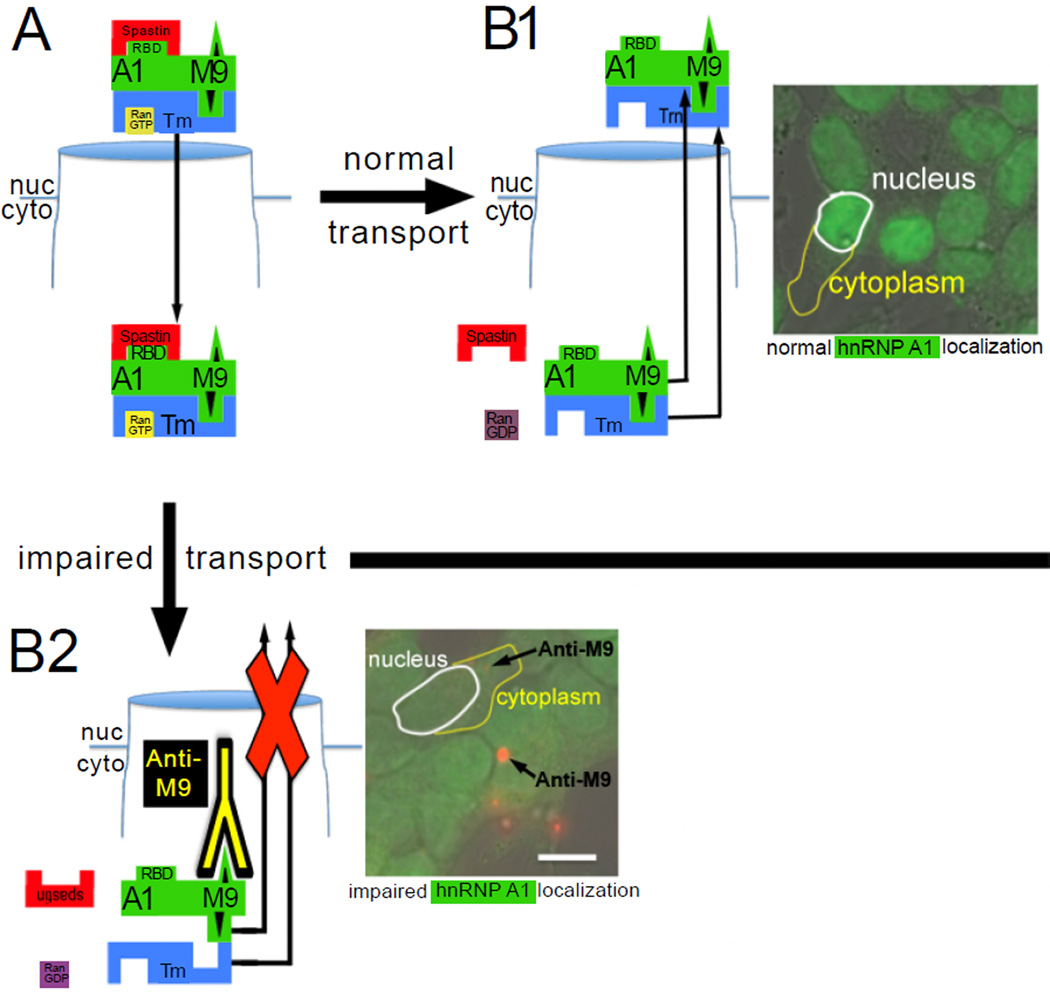

Because of the similarities between HAM/TSP and progressive forms of MS, we hypothesized that antibodies isolated from MS patients would also immunoreact with hnRNP A1[7] (Figure 1). This was found to be true. IgG isolated from MS patients preferentially immunoreacted with CNS neurons compared to systemic organs [7]. Further, MS IgG immunoreacted with hnRNP A1 and like HAM/TSP IgG, with the same epitope contained within M9 [7]. 37/37 MS patients reacted with hnRNP A1-M9 in contrast to HC (n=8) and Alzheimer’s patients (n=5, a control for neurodegenerative disease) [7]. CSF samples also immunoreacted with hnRNP A1-M9 and other groups have independently verified that HAM/TSP and MS IgG (isolated from CSF) react with hnRNP A1 [7,111–113]. Clinically, approximately 90% of the MS patients tested had evidence of corticospinal dysfunction such as paraparesis, hyperreflexia or extensor plantar responses [7]. Next, we performed a series of experiments designed to test whether anti-hnRNP A1-M9 antibodies would alter hnRNP A1 function and contribute to neurodegeneration. M9 acts as both a nuclear export sequence (NES) and nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and is required for the transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [105,108] (Figure 2). Nucleocytoplasmic transport occurs when mRNA binds hnRNP A1 via its RNA binding domains and a protein named transportin binds hnRNP A1 via M9. The complex binds RanGTP in the nucleus and the entire complex is transported through the nuclear pore to the cytoplasm [114]. Upon depositing mRNA in the cytoplasm, hnRNP A1 is transported back through the nuclear pore to the nucleus. In addition to mRNA nucleocytoplasmic transport, hnRNP A1 also plays a role in the regulation of mRNA transcription and translation [105,106]. Upon exposure to anti-hnRNP A1-M9 antibodies in vitro, neurons showed evidence of neurodegeneration [7,115]. Microarray analyses of the neurons compared to neurons exposed to control antibodies showed preferential expression of genes related to both hnRNP A1 function and the clinical phenotype of progressive MS patients. Specifically, the spinal paraplegia genes (SPGs) were down regulated [7]. Mutations in SPGs cause hereditary spastic paraparesis (HSP), genetic disorders clinically indistinguishable from progressive MS [6,116,117]. Importantly, SPGs were also found to be down regulated in CNS neurons purified from MS patients compared to neurons from control brains [7]. In separate in vitro experiments, anti-M9 antibodies were found to enter neurons by utilizing clathrin-mediated endocytosis, a mechanism identical to antibodies isolated from ALS patients [118,119]. Neuronal cells exposed to the anti-M9 antibodies caused apoptosis and reduction in ATP levels [118]. Importantly, in contrast to control antibodies, anti-M9 antibodies altered the localization of hnRNP A1 within neurons [118]. hnRNP A1 shuttles continuously between the nucleus and cytoplasm. At equilibrium, hnRNP A1 is predominantly localized to the nucleus [120]. Upon exposure to anti-M9 antibodies, hnRNP A1 was localized equally between the nucleus and cytoplasm. These data indicate that anti-M9 antibodies enter neurons via clathrin-mediated endocytosis and then target hnRNP A1 within the cytoplasm, altering its function and localization [118] (Figure 2). Considering that spastic paraparesis is the predominant symptom of progressive forms of MS and there appears to be a molecular relationship between SPGs and hnRNP A1, what might be the mechanism by which anti-M9 antibodies alter SPG expression? Spastin is the most common SPG, and was one of several SPGs altered when neuronal cells were exposed to anti-M9 antibodies. Spastin contains an AAA site and thus is a member of the ATPases associated with various cellular activities (AAA-ATPases), which are involved in microtubule regulation as well as proteosome and endosome function [117,121,122]. Spastin contains an MIT (microtubule interacting and trafficking protein) site [121,123] and has been shown to play a role in microtubule stability in neurons [121], and in turn, to normal synaptic growth and transmission [124]. In addition, spastin contains several classic NLSs [125] as well as leucine-rich NESs [126]. Analysis of spastin RNA by ‘the database of RNA-binding protein specificities’ (http://rbpdb.ccbr.utoronto.ca) revealed that spastin RNA contains the binding sequence (UAGGGA) required to bind hnRNP A1 via its RNA binding domain. In addition, data indicates that spastin RNA binds hnRNP A1[2]. Thus, upon targeting hnRNP A1-M9, anti-M9 antibodies might alter the location or metabolism of spastin, which would result in spastic paraparesis (Figure 2). Further studies are needed to evaluate this mechanism using in vivo models of immune mediated neurodegeneration.

Figure 2. hnRNP A1 nucleocytoplasmic transport.

(A) Under normal conditions, hnRNP A1 (A1) binds transportin (Trn) via its M9 nucleocytoplasmic transport sequence; spastin RNA binds RNA binding domains (RBD) and upon RanGTP binding to Trn, the complex is transported through the nuclear pore to the cytoplasm (cyto). (B1) spastin and RanGTP are released into the cytoplasm, RanGTP is converted to RanGDP and hnRNP A1 and transportin return to the nucleus (nuc). The photomicrograph of SK-N-SH neurons shows that the vast majority of hnRNP A1 (green staining) is in the nucleus [118]. (B2) Under pathologic conditions when anti-M9 antibodies are present in neurons, hnRNP A1 transport from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is inhibited, thus hnRNP A1 is present equally in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. This may result in abnormal metabolism or transport of spastin and inhibition of binding of hnRNP A1 to Trn because of steric hindrance of the anti-M9 antibodies. The photomicrograph shows hnRNP A1 staining in the nucleus and cytoplasm, as well as fuorescently labeled anti-M9 antibodies (red) present in the neuronal cytoplasm [118].

Antibodies to Both Myelin and Non-myelin Self-antigens

Several studies addressed both myelin and non-myelin antigens. For example, a different model developed from the myelin glycoprotein isolation of contactin-2/TAG-1 [55,95,127]. Unlike the neurofascin data, differences in immunoreactivity to contactin-2 between MS patients and patients with OIND was found in CSF but not in sera [55]. Interestingly, the animal model also showed different results. Anti-contactin-2/TAG-1 antibodies did not contribute to the pathogenesis of EAE. Instead, a T-cell response to contactin-2/TAG-1 followed by infusion of anti-MOG antibodies augmented disease and mimicked gray matter inflammation and damage as is seen in MS patients [55,127]. The lack of contribution of anti-contactin-2/TAG-1 antibodies in this model might be explained by the location of contactin-2/TAG-1, which is contained within the paranodal region adjacent to the node of Ranvier, and is covered by myelin, thus making antibody access difficult [95] (Table 1).

When lipid microarrays were analyzed using myelin and non-myelin lipids, CSF from MS patients showed preferential immunoreactivity to specific lipid profiles [128]. Comparing MS to OND patients, there was increased immunoreactivity to lipids containing sulfatide, 3β-hydroxy-5α-cholestan-15-one, oxidized phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidyl ethanolamine, lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine, sphingomyelin and asialo-GM1 (a ganglioside) [128]. When comparing SPMS to OND, GM1 and asialo-GM1 showed preferentially immunoreactivity [128]. Interestingly, immunization with sulfatide in a PLP139–151 model of EAE worsened disease, as did infusion of anti-sulfatide antibodies [128].

Van Noort et al., discovered a robust pro-inflammatory T-cell response to αB-crystallin (CRYAB), which was found to be overexpressed in MS compared to HC brains [129]. CRYAB is a small heat shock protein (HSP) and has neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic functions [54]. CRYAB−/− mice showed worse EAE associated with higher T1 and TH17 cytokine secretion [54]. Interestingly, RRMS patients showed preferential antibody response to CRYAB by antigen microarray [54]. Mice with EAE also developed antibodies to CRYAB. Taken together, these data suggest that antibodies to CRYAB, a neuroprotective agent, might contribute to the pathogenesis of MS [54].

A tripartite antigen microarray consisting of a series of ‘CNS’ (myelin and non-myelin), HSP and lipid antigens was used to examine autoantibody signatures in subtypes of MS [130]. Compared to HC, RRMS patients were distinguished by differential IgM and IgG immunoreactivities to CNS and HSP proteins. In the CNS group, in addition to myelin antigens (MBP, PLP, MOG, MOBP), several non-myelin antigens showed differential immunoreactivity including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), lactocerebroside and beta-amyloid [130]. Similarly, PPMS patients were differentiated from HC by immunoreactivity to some myelin antigens as well as the non-myelin antigens beta-amyloid, neurofilament 68 kDa and superoxide dismutase [130]. Interestingly, compared to RRMS, PPMS and SPMS patients had relatively low immunoreactivity to HSPs. In addition, serum samples were compared from pattern I (T-cell mediated), and pattern 2 (antibody/complement mediated) type MS pathologies. In these studies, differential autoantibody immunoreactivities were found to myelin (MOG, PLP), non-myelin (neurofilament 160kDa) and lipid targets. Administration of some of the lipids augmented MOG35–55 EAE [130].

Conclusion

MS is a complex, multifactorial disease. Data suggests MS is a two-phase disease [2,131–133]. The early phase is predominantly inflammatory/demyelinating and the secondary/progressive phase is neurodegenerative. However, many studies show that neuronal and axonal damage are present in early phases of MS, suggesting mechanisms of neurodegeneration contribute to MS pathogenesis throughout the disease. Recent studies have unveiled that immune responses to non-myelin target antigens contribute to neurodegeneration and the pathogenesis of MS. Considering there are no effective therapies for progressive forms of MS, a comprehensive understanding of antibody-mediated mechanisms of neurodegeneration in MS should lead to novel therapeutic agents to treat it, and thus, reduce disability.

Acknowledgements

This work is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs. This study was funded by a VA Merit Review Award (MCL), NIH Summer Medical Student Research Grant (USPHS Grant DK-007405-29) (CC) and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Multiple Sclerosis Research Fund.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Michael Levin and Sangmin Lee have a patent pending titled “Biomarker for neurodegeneration in neurological disease”.

References

- 1.Dutta R, Trapp BD. Pathogenesis of axonal and neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;68:S22–S31. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275229.13012.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin MC, Lee S, Gardner LA, Shin Y, Douglas JN, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of neurodegeneration based on the phenotypic expression of progressive forms of immune-mediated neurologic disease. Degenerative Neurological and Neuromuscular Disease. 2012;2:175–187. doi: 10.2147/DNND.S38353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassmann H, Brück W, Lucchinetti CF. The immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson JW, Trapp BD. Neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:107–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.09.008. vi-vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLuca GC, Ramagopalan SV, Cader MZ, Dyment DA, Herrera BM, et al. The role of hereditary spastic paraplegia related genes in multiple sclerosis. A study of disease susceptibility and clinical outcome. J Neurol. 2007;254:1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Xu L, Shin Y, Gardner L, Hartzes A, et al. A potential link between autoimmunity and neurodegeneration in immune-mediated neurological disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;235:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis--the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:942–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trapp BD, Nave KA. Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geurts JJ, Barkhof F. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:841–851. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lassmann H, Lucchinetti CF. Cortical demyelination in CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Neurology. 2008;70:332–333. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000298724.89870.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, Moll NM, Roemer SF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2188–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson JW, Bö L, Mörk S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:389–400. doi: 10.1002/ana.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, Lucchinetti CF, Rauschka H, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009;132:1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher E, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Rudick RA. Gray matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:255–265. doi: 10.1002/ana.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisniku LK, Chard DT, Jackson JS, Anderson VM, Altmann DR, et al. Gray matter atrophy is related to long-term disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:247–254. doi: 10.1002/ana.21423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geurts JJ. Is progressive multiple sclerosis a gray matter disease? Ann Neurol. 2008;64:230–232. doi: 10.1002/ana.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucchinetti C, Brück W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, et al. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:707–717. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kutzelnigg A, Lucchinetti CF, Stadelmann C, Brück W, Rauschka H, et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:2705–2712. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH. Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 1997;120:393–399. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro cell mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic chroiomeningitis within a syngeneic or semi-allogenic system. Nature. 1974;248:701–702. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haskins K, Kubo R, White J, Pigeon M, Kappler J, et al. The major histocompatibility complex-restricted antigen receptor on T cells. I. Isolation with a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1149–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zamvil S, Nelson P, Trotter J, Mitchell D, Knobler R, et al. T-cell clones specific for myelin basic protein induce chronic relapsing paralysis and demyelination. Nature. 1985;317:355–358. doi: 10.1038/317355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamvil SS, Mitchell DJ, Moore AC, Kitamura K, Steinman L, et al. T-cell epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein that induces encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1986;324:258–260. doi: 10.1038/324258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wucherpfennig KW, Hafler DA, Strominger JL. Structure of human T-cell receptors specific for an immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide: positioning of T-cell receptors on HLA-DR2/peptide complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8896–8900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren KG, Catz I, Steinman L. Fine specificity of the antibody response to myelin basic protein in the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis: the minimal B-cell epitope and a model of its features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11061–11065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin R, McFarland HF. Immunological aspects of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1995;32:121–182. doi: 10.3109/10408369509084683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forsthuber TG, Shive CL, Wienhold W, de Graaf K, Spack EG, et al. T cell epitopes of human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein identified in HLA-DR4 (DRB1*0401) transgenic mice are encephalitogenic and are presented by human B cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:7119–7125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinman L, Zamvil SS. How to successfully apply animal studies in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis to research on multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:12–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.20913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke MA, Segal BM. Th17 and Th1 responses directed against the immunizing epitope, as opposed to secondary epitopes, dominate the autoimmune repertoire during relapses of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1685–1693. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratts RB, Karandikar NJ, Hussain RZ, Choy J, Northrop SC, et al. Phenotypic characterization of autoreactive T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;178:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wucherpfennig KW, Allen PM, Celada F, Cohen IR, De Boer R, et al. Polyspecificity of T cell and B cell receptor recognition. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lassmann H. Experimental models of multiple sclerosis. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2007;163:651–655. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(07)90474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamoorthy G, Saxena A, Mars LT, Domingues HS, Mentele R, et al. Myelin-specific T cells also recognize neuronal autoantigen in a transgenic mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2009;15:626–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lassmann H. Axonal and neuronal pathology in multiple sclerosis: what have we learnt from animal models. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovett-Racke AE, Yang Y, Racke MK. Th1 versus Th17: are T cell cytokines relevant in multiple sclerosis? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becher B, Segal BM. T(H)17 cytokines in autoimmune neuro-inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:707–712. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin R, Voskuhl R, Flerlage M, McFarlin DE, McFarland HF. Myelin basic protein-specific T-cell responses in identical twins discordant or concordant for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:524–535. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelfrey CM, Tranquill LR, Vogt AB, McFarland HF. T cell response to two immunodominant proteolipid protein (PLP) peptides in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Mult Scler. 1996;1:270–278. doi: 10.1177/135245859600100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaye JF, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Mendel I, Flechter S, Hoffman M, et al. The central nervous system-specific myelin oligodendrocytic basic protein (MOBP) is encephalitogenic and a potential target antigen in multiple sclerosis (MS) J Neuroimmunol. 2000;102:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hafler DA, Slavik JM, Anderson DE, O’Connor KC, De Jager P, et al. Multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:208–231. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFarland HF, Martin R. Multiple sclerosis: a complicated picture of autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:913–919. doi: 10.1038/ni1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaushansky N, Altmann DM, David CS, Lassmann H, Ben-Nun A. DQB1*0602 rather than DRB1*1501 confers susceptibility to multiple sclerosis-like disease induced by proteolipid protein (PLP) J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jilek S, Schluep M, Pantaleo G, Du Pasquier RA. MOBP-specific cellular immune responses are weaker than MOG-specific cellular immune responses in patients with multiple sclerosis and healthy subjects. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:539–543. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke MA, Chensue SW, Segal BM. EAE mediated by a non-IFN-γ/non-IL-17 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2340–2348. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke MA, Segal BM. IL-23 modulated myelin-specific T cells induce EAE via an IFNγ driven, IL-17 independent pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinman L. Mixed results with modulation of TH-17 cells in human autoimmune diseases. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:41–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friese MA, Fugger L. Autoreactive CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis: a new target for therapy? Brain. 2005;128:1747–1763. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goverman J, Perchellet A, Huseby ES. The role of CD8(+) T cells in multiple sclerosis and its animal models. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:239–245. doi: 10.2174/1568010053586264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saxena A, Martin-Blondel G, Mars LT, Liblau RS. Role of CD8 T cell subsets in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3758–3763. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ji Q, Castelli L, Goverman JM. MHC class I-restricted myelin epitopes are cross-presented by Tip-DCs that promote determinant spreading to CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:254–261. doi: 10.1038/ni.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hur EM, Youssef S, Haws ME, Zhang SY, Sobel RA, et al. Osteopontin-induced relapse and progression of autoimmune brain disease through enhanced survival of activated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:74–83. doi: 10.1038/ni1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinman L. A molecular trio in relapse and remission in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:440–447. doi: 10.1038/nri2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ousman SS, Tomooka BH, van Noort JM, Wawrousek EF, O’Connor KC, et al. Protective and therapeutic role for alphaB-crystallin in autoimmune demyelination. Nature. 2007;448:474–479. doi: 10.1038/nature05935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Derfuss T, Parikh K, Velhin S, Braun M, Mathey E, et al. Contactin-2/TAG-1-directed autoimmunity is identified in multiple sclerosis patients and mediates gray matter pathology in animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8302–8307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901496106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silber E, Semra YK, Gregson NA, Sharief MK. Patients with progressive multiple sclerosis have elevated antibodies to neurofilament subunit. Neurology. 2002;58:1372–1381. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eikelenboom MJ, Petzold A, Lazeron RH, Silber E, Sharief M, et al. Multiple sclerosis: Neurofilament light chain antibodies are correlated to cerebral atrophy. Neurology. 2003;60:219–223. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000041496.58127.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathey EK, Derfuss T, Storch MK, Williams KR, Hales K, et al. Neurofascin as a novel target for autoantibody-mediated axonal injury. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2363–2372. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Srivastava R, Aslam M, Kalluri SR, Schirmer L, Buck D, et al. Potassium channel KIR4.1 as an immune target in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:115–123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huizinga R, Heijmans N, Schubert P, Gschmeissner S, ‘t Hart BA, et al. Immunization with neurofilament light protein induces spastic paresis and axonal degeneration in Biozzi ABH mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:295–304. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e318040ad5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huizinga R, Linington C, Amor S. Resistance is futile: antineuronal autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Racke MK. The role of B cells in multiple sclerosis: rationale for B-cell-targeted therapies. Curr Opin Neurol 21 Suppl. 2008;1:S9–9S18. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000313359.61176.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lisak RP, Zwiman B, Norman M. Antimyelin antibodies in neurologic diseases. Immunofluorescent demonstration. Arch Neurol. 1975;32:163–167. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490450043005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Panitch HS, Hooper CJ, Johnson KP. CSF antibody to myelin basic protein. Measurement in patients with multiple sclerosis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:206–209. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500530044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Górny MK, Wróblewska Z, Pleasure D, Miller SL, Wajgt A, et al. CSF antibodies to myelin basic protein and oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. Acta Neurol Scand. 1983;67:338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb03151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wajgt A, Górny M. CSF antibodies to myelin basic protein and to myelin-associated glycoprotein in multiple sclerosis. Evidence of the intrathecal production of antibodies. Acta Neurol Scand. 1983;68:337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb04841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao BG, Linington C, Link H. Antibodies to myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with multiple sclerosis and controls. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;31:91–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reindl M, Linington C, Brehm U, Egg R, Dilitz E, et al. Antibodies against the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and the myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases: a comparative study. Brain. 1999;122:2047–2056. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karni A, Bakimer-Kleiner R, Abramsky O, Ben-Nun A. Elevated levels of antibody to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is not specific for patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:311–315. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berger T, Rubner P, Schautzer F, Egg R, Ulmer H, et al. Antimyelin antibodies as a predictor of clinically definite multiple sclerosis after a first demyelinating event. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:139–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greeve I, Sellner J, Lauterburg T, Walker U, Rösler KM, et al. Antimyelin antibodies in clinically isolated syndrome indicate the risk of multiple sclerosis in a Swiss cohort. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tomassini V, De Giglio L, Reindl M, Russo P, Pestalozza I, et al. Antimyelin antibodies predict the clinical outcome after a first episode suggestive of MS. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1086–1094. doi: 10.1177/1352458507077622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lampasona V, Franciotta D, Furlan R, Zanaboni S, Fazio R, et al. Similar low frequency of anti-MOG IgG and IgM in MS patients and healthy subjects. Neurology. 2004;62:2092–2094. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127615.15768.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mantegazza R, Cristaldini P, Bernasconi P, Baggi F, Pedotti R, et al. Anti-MOG autoantibodies in Italian multiple sclerosis patients: specificity, sensitivity and clinical association. Int Immunol. 2004;16:559–565. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rauer S, Euler B, Reindl M, Berger T. Antimyelin antibodies and the risk of relapse in patients with a primary demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:739–742. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.077784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang H, Munger KL, Reindl M, O’Reilly EJ, Levin LI, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies and multiple sclerosis in healthy young adults. Neurology. 2008;71:1142–1146. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316195.52001.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khalil M, Reindl M, Lutterotti A, Kuenz B, Ehling R, et al. Epitope specificity of serum antibodies directed against the extracellular domain of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: Influence of relapses and immunomodulatory treatments. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;174:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim ET, Berger T, Reindl M, Dalton CM, Fernando K, et al. Antimyelin antibodies do not allow earlier diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:492–494. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1187sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuhle J, Pohl C, Mehling M, Edan G, Freedman MS, et al. Lack of association between antimyelin antibodies and progression to multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:371–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lalive PH, Menge T, Delarasse C, Della Gaspera B, Pham-Dinh D, et al. Antibodies to native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein are serologic markers of early inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2280–2285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Menge T, von Büdingen HC, Lalive PH, Genain CP. Relevant antibody subsets against MOG recognize conformational epitopes exclusively exposed in solid-phase ELISA. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3229–3239. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pittock SJ, Reindl M, Achenbach S, Berger T, Bruck W, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in pathologically proven multiple sclerosis: frequency, stability and clinicopathologic correlations. Mult Scler. 2007;13:7–16. doi: 10.1177/1352458506072189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Belogurov AA, Jr, Kurkova IN, Friboulet A, Thomas D, Misikov VK, et al. Recognition and degradation of myelin basic protein peptides by serum autoantibodies: novel biomarker for multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2008;180:1258–1267. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hedegaard CJ, Chen N, Sellebjerg F, Sørensen PS, Leslie RG, et al. Autoantibodies to myelin basic protein (MBP) in healthy individuals and in patients with multiple sclerosis: a role in regulating cytokine responses to MBP. Immunology. 2009;128:e451–e461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chan A, Decard BF, Franke C, Grummel V, Zhou D, et al. Serum antibodies to conformational and linear epitopes of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein are not elevated in the preclinical phase of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1189–1192. doi: 10.1177/1352458510376406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tewarie P, Teunissen CE, Dijkstra CD, Heijnen DA, Vogt M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid anti-whole myelin antibodies are not correlated to magnetic resonance imaging activity in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;251:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Owens GP, Bennett JL, Lassmann H, O’Connor KC, Ritchie AM, et al. Antibodies produced by clonally expanded plasma cells in multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:639–649. doi: 10.1002/ana.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rawes JA, Calabrese VP, Khan OA, DeVries GH. Antibodies to the axolemma-enriched fraction in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. Mult Scler. 1997;3:363–369. doi: 10.1177/135245859700300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sadatipour BT, Greer JM, Pender MP. Increased circulating antiganglioside antibodies in primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:980–983. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan A, Rao MV, Veeranna, Nixon RA. Neuroflaments at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3257–3263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Norgren N, Sundström P, Svenningsson A, Rosengren L, Stigbrand T, et al. Neuroflament and glial fibrillary acidic protein in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:1586–1590. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142988.49341.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huizinga R, Gerritsen W, Heijmans N, Amor S. Axonal loss and gray matter pathology as a direct result of autoimmunity to neurofilaments. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huizinga R, van der Star BJ, Kipp M, Jong R, Gerritsen W, et al. Phagocytosis of neuronal debris by microglia is associated with neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Glia. 2012;60:422–431. doi: 10.1002/glia.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lily O, Palace J, Vincent A. Serum autoantibodies to cell surface determinants in multiple sclerosis: a flow cytometric study. Brain. 2004;127:269–279. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meinl E, Derfuss T, Krumbholz M, Pröbstel AK, Hohlfeld R. Humoral autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;306:180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Derfuss T, Linington C, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. Axoglial antigens as targets in multiple sclerosis: implications for axonal and grey matter injury. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:753–761. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Levin MC, Lee SM, Kalume F, Morcos Y, Dohan FC, Jr, et al. Autoimmunity due to molecular mimicry as a cause of neurological disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dalmau J, Furneaux HM, Gralla RJ, Kris MG, Posner JB. Detection of the anti-Hu antibody in the serum of patients with small cell lung cancer--a quantitative western blot analysis. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:544–552. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Levin MC, Krichavsky M, Berk J, Foley S, Rosenfeld M, et al. Neuronal molecular mimicry in immune-mediated neurologic disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:87–98. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Levin MC, Lehky TJ, Flerlage AN, Katz D, Kingma DW, et al. Immunopathogenesis of HTLV-1 associated neurologic disease based on a spinal cord biopsy from a patient with HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) New Eng J Med. 1997;336:839–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703203361205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee SM, Morcos Y, Jang H, Stuart JM, Levin MC. HTLV-1 induced molecular mimicry in neurologic disease. In: Oldstone M, editor. Molecular Mimicry: Infection Inducing Autoimmune Disease. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee S, Levin MC. Molecular mimicry in neurological disease: what is the evidence? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1161–1175. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Levin MC, Lee SM, Morcos Y, Brady J, Stuart J. Cross-reactivity between immunodominant human T lymphotropic virus type I tax and neurons: implications for molecular mimicry. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1514–1517. doi: 10.1086/344734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dreyfuss G, Kim VN, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Han SP, Tang YH, Smith R. Functional diversity of the hnRNPs: past, present and perspectives. Biochem J. 2010;430:379–392. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee SM, Dunnavant FD, Jang H, Zunt J, Levin MC. Autoantibodies that recognize functional domains of hnRNPA1 implicate molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of neurological disease. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee BJ, Cansizoglu AE, Süel KE, Louis TH, Zhang Z, et al. Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin beta 2. Cell. 2006;126:543–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jernigan M, Morcos Y, Lee SM, Dohan FC, Jr, Raine C, et al. IgG in brain correlates with clinicopathological damage in HTLV-1 associated neurologic disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1320–1327. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000059866.03880.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kalume F, Lee SM, Morcos Y, Callaway JC, Levin MC. Molecular mimicry: cross-reactive antibodies from patients with immune-mediated neurologic disease inhibit neuronal firing. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:82–89. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sueoka E, Yukitake M, Iwanaga K, Sueoka N, Aihara T, et al. Autoantibodies against heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein B1 in CSF of MS patients. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:778–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.García-Vallejo F, Domínguez MC, Tamayo O. Autoimmunity and molecular mimicry in tropical spastic paraparesis/human T-lymphotropic virus-associated myelopathy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38:241–250. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yukitake M, Sueoka E, Sueoka-Aragane N, Sato A, Ohashi H, et al. Significantly increased antibody response to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients but not in patients with human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. J Neurovirol. 2008;14:130–135. doi: 10.1080/13550280701883840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cook A, Bono F, Jinek M, Conti E. Structural biology of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.161529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Douglas JN, Gardner LA, Lee S, Shin Y, Groover CJ, et al. Antibody transfection into neurons as a tool to study disease pathogenesis. J Vis Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Soderblom C, Blackstone C. Traffic accidents: molecular genetic insights into the pathogenesis of the hereditary spastic paraplegias. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Salinas S, Proukakis C, Crosby A, Warner TT. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical features and pathogenetic mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Douglas J, Gardner L, Levin MC. Antibodies to an intracellular antigen penetrate neuronal cells and cause deleterious effects. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2013;4:134. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mohamed HA, Mosier DR, Zou LL, Siklós L, Alexianu ME, et al. Immunoglobulin Fc gamma receptor promotes immunoglobulin uptake, immunoglobulin-mediated calcium increase, and neurotransmitter release in motor neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:110–116. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Michael WM, Choi M, Dreyfuss G. A nuclear export signal in hnRNP A1: a signal-mediated, temperature-dependent nuclear protein export pathway. Cell. 1995;83:415–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roll-Mecak A, Vale RD. Structural basis of microtubule severing by the hereditary spastic paraplegia protein spastin. Nature. 2008;451:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hazan J, Fonknechten N, Mavel D, Paternotte C, Samson D, et al. Spastin, a new AAA protein, is altered in the most frequent form of autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia. Nat Genet. 1999;23:296–303. doi: 10.1038/15472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Salinas S, Carazo-Salas RE, Proukakis C, Schiavo G, Warner TT. Spastin and microtubules: Functions in health and disease. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2778–2782. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Trotta N, Orso G, Rossetto MG, Daga A, Broadie K. The hereditary spastic paraplegia gene, spastin, regulates microtubule stability to modulate synaptic structure and function. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1135–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Beetz C, Brodhun M, Moutzouris K, Kiehntopf M, Berndt A, et al. Identification of nuclear localisation sequences in spastin (SPG4) using a novel Tetra-GFP reporter system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Claudiani P, Riano E, Errico A, Andolfi G, Rugarli EI. Spastin subcellular localization is regulated through usage of different translation start sites and active export from the nucleus. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Steinman L. The gray aspects of white matter disease in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8083–8084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903377106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kanter JL, Narayana S, Ho PP, Catz I, Warren KG, et al. Lipid microarrays identify key mediators of autoimmune brain inflammation. Nat Med. 2006;12:138–143. doi: 10.1038/nm1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.van Noort JM, van Sechel AC, Bajramovic JJ, el Ouagmiri M, Polman CH, et al. The small heat-shock protein alpha B-crystallin as candidate autoantigen in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 1995;375:798–801. doi: 10.1038/375798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Quintana FJ, Farez MF, Viglietta V, Iglesias AH, Merbl Y, et al. Antigen microarrays identify unique serum autoantibody signatures in clinical and pathologic subtypes of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18889–18894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806310105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Steinman L. Multiple sclerosis: a two-stage disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:762–764. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dutta R, Trapp BD. Mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction and degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lassmann H, van Horssen J. The molecular basis of neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3715–3723. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]