Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Post-sternotomy mediastinitis is a severe complication of open heart surgery resulting in prolonged hospital stay and increased mortality. Vacuum-assisted closure is commonly used as treatment for post-sternotomy mediastinitis, but has some disadvantages. Primary closure over high vacuum suction Redon drains previously has shown to be an alternative approach with promising results. We report our short- and long-term results of Redon therapy-treated mediastinitis.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of 124 patients who underwent primary closure of the sternum over Redon drains as treatment for post-sternotomy mediastinitis in Amphia Hospital (Breda, Netherlands) and St. Antonius Hospital (Nieuwegein, Netherlands). Patient characteristics, preoperative risk factors and procedure-related variables were analysed. Duration of therapy, hospital stay, treatment failure and mortality as well as C-reactive protein and blood leucocyte counts on admission and at various time intervals during hospital stay were determined.

RESULTS

Mean age of patients was 68.7 ± 11.0 years. In 77.4%, the primary surgery was coronary artery bypass grafting. Presentation of mediastinitis was 15.2 ± 9.8 days after surgery. Duration of Redon therapy was 25.9 ± 18.4 days. Hospital stay was 32.8 ± 20.7 days. Treatment failure occurred in 8.1% of patients. In-hospital mortality was 8.9%. No risk factors were found for mortality or treatment failure. The median follow-up time was 6.6 years. One- and 5-year survivals were 86 and 70%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary closure using Redon drains is a feasible, simple and efficient treatment modality for post-sternotomy mediastinitis.

Keywords: Mediastinitis, Infection, Redon drainage, Sternotomy

INTRODUCTION

Post-sternotomy mediastinitis is a rare but devastating complication of cardiac surgery with prolonged hospitalization and mortality rates up to 25% [1]. In the past decades, several treatment modalities have been described including wound treatment with open dressings, closed irrigation and omental and myocutaneous flap reconstruction [1]. Nowadays, vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) is an established therapy for the treatment of post-sternotomy mediastinitis, resulting in decreased mortality and hospital stay [2–6]. VAC is associated with some important disadvantages. Using VAC therapy, long-lasting in-hospital treatment is often required. Patients have a prolonged period with an open sternum, which is an invalidating experience for them. Additionally, VAC sponges have to be replaced twice a week. This can be painful, leads to increased risk of super-infection and is relatively time-consuming and expensive. Serious adverse events during VAC therapy like right ventricular rupture have been reported, urging the need for alternative treatment modalities [3, 7]. In 1989, Durandy et al. [8] introduced a closed drainage technique using high negative pressure with Redon drains. These drains were initially used in orthopaedic surgery, promoting adhesion of tissue layers, thereby minimizing haematoma formation and decreasing infection risks. A primary closed sternum, less wound debridement and shorter length of treatment are the possible benefits of using this technique for the treatment of post-sternotomy mediastinitis. Since the introduction of the method, five studies have shown Redon therapy to be feasible and safe [9–13]. Currently, there are few studies with greater numbers of treated patients [11, 13]. In this large study, the results of two hospitals using closed drainage with high vacuum Redon drains for the treatment of post-sternotomy mediastinitis are presented and discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and data collection

The study was approved by the ethics committees of both St. Antonius Hospital (Nieuwegein, Netherlands) and Amphia Hospital (Breda, Netherlands); the need for individual patient consent was waived.

A total of 35 429 patients underwent cardiac operation via median sternotomy between 1 January 2000 and 1 January 2011 in these centres. Mediastinitis was determined according to the definition given by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [14]. A total of 252 patients developed mediastinitis (0.71%). Patients treated with closed drainage using Redon catheters (n = 124) were included.

Patient characteristics, risk factors, procedure-related variables and treatment-related data were collected from both prospectively designed databases as individual medical records. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of >140 mmHg. Renal failure was defined as a creatinine blood level of ≥120 µmol/l. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2. Treatment failure was defined as the need for reintervention.

Treatment

All patients underwent emergency surgical intervention under general anaesthesia. The sternotomy wound was fully reopened and extensive debridement was performed. The wound was irrigated with diluted povidone-iodine solution and saline. After debridement and irrigation, the wound was closed over Redon drains.

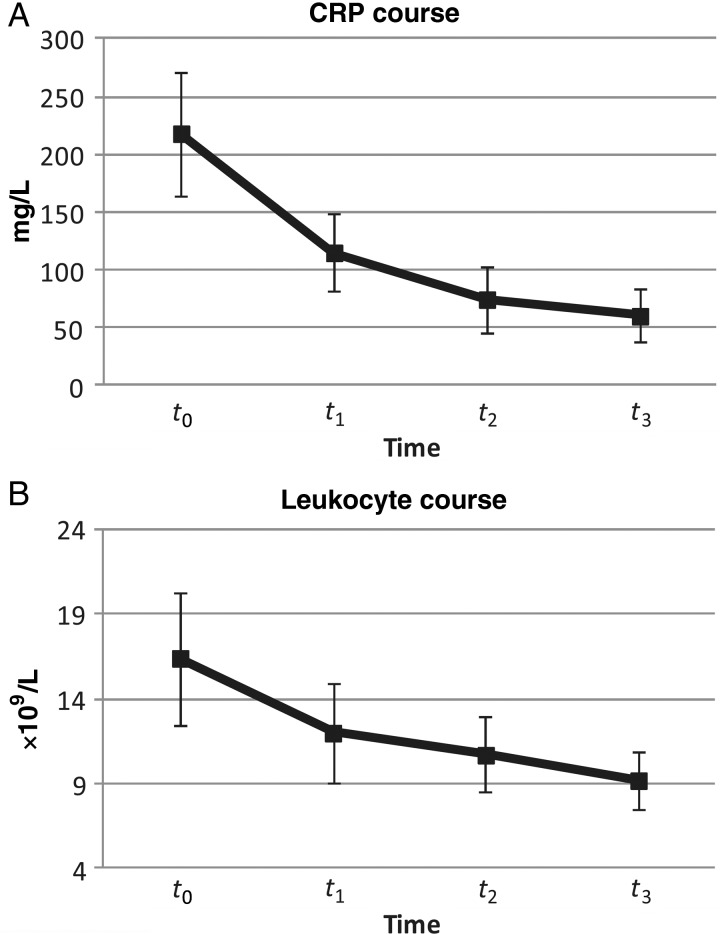

Closed drainage with Redon catheters

In this technique, two to eight Redon drains were positioned in the infected area including the pericardial sac and subcutaneous tissue [8]. The number of Redon drains depended on the size of the residual cavity. The sternum was closed and subcutaneous tissue and skin were approximated using interrupted sutures. Redon drains were connected to numbered plastic bottles with a negative pressure of 700 mmHg (Fig. 1). The effluence from each bottle was cultured once every 3 days. The corresponding drain was removed when two or more consecutive cultures were negative. All patients in Amphia Hospital were treated with intravenous antibiotics until the last drain was removed. Hereafter, all patients were treated with oral antibiotics for 1 week. All patients in St. Antonius Hospital were treated with intravenous antibiotics until there was no clinical sign of infection.

Figure 1:

Patient during Redon treatment. The vacuum bottles lie in the box on his left. In the lower right corner a close-up of the drain entries.

Outcome and evaluation

Blood samples for leucocyte count, haemoglobin and C-reactive protein were analysed on admission, at diagnosis of mediastinitis (t0), at t1 (3–7 days after t0), at t2 (8–13 days after t0) and at t3 (14–21 days after t0). The time interval between the primary surgery and the reoperation for mediastinitis was evaluated. The length of hospital stay, duration of Redon drainage and antibiotic therapy were reported. The long-term follow-up was performed by telephone consultation with the general practitioner in October 2011.

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics are presented. Comparison of groups was performed by Student's t-test when the dependent variable was normally divided, Mann–Whitney test when the dependent variable was ordinal or χ2 test when the dependent variable was categorical. Survival was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier estimates. The variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as absolute numbers with percentages. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS® (SPSS 17.0 for windows, IBM Corporation 1994, 2011).

RESULTS

Patient population and characteristics

Patient characteristics and laboratory values are given in Table 1. Variables related to the initial surgical procedure are listed in Table 2. The interval between operation and reoperation for mediastinitis was 15.2 ± 9.8 days. Patient groups of both centres were comparable regarding preoperative risk factors, operation data and primary outcomes (a selection is shown in Table 3). Subsequently, patients of both hospitals were analysed as one group.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics

| Patients, n = 124 | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 94 (75.8%) |

| Age (years) | 68.7 ± 11.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 23 (18.5%) |

| Diabetes | 46 (37.1%) |

| Hypertension | 66 (53.2%) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 5 (4.0%) |

| Renal failure | 15 (12.1%) |

| Body mass index | 28.5 ± 4.2 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 13.1 ± 21.3 |

| Leucocyte count (×109) | 8.7 ± 3.5 |

| Haemoglobin (mmol/l) | 8.3 ± 1.2 |

Table 2:

Surgical procedure variables

| Patients, n = 124 | |

|---|---|

| Previous surgical procedure | 42 (33.9%) |

| Emergency operation | 9 (7.3%) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 96 (77.4%) |

| Left internal mammary artery | 74 (59.7%) |

| Right internal mammary artery | 7 (5.6%) |

| Aortic valve replacement | 21 (16.9%) |

| Mitral valve replacement/mitral valve repair | 12 (9.7%) |

| Duration of surgery | 226.5 ± 80.7 |

| Extra corporal circulation time | 120.1 ± 66.9 |

| Cross clamp time | 84.0 ± 53.6 |

Table 3:

Pre-, peri- and postoperative data of the two hospitals compared

| St. Antonius hospital, n = 43 | Amphia hospital, n = 81 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 36 (83.7%) | 58 (71.6%) | 0.134 |

| Age (years) | 66.4 ± 12.1 | 69.5 ± 10.6 | 0.141 |

| COPD | 9 (20.9%) | 14 (18.4%) | 0.739 |

| BMI | 28.1 ± 4.9 | 28.6 ± 4.0 | 0.611 |

| Creatinine | 93.6 ± 31.6 | 100 ± 60.4 | 0.515 |

| CABG | 31 (72.1%) | 65 (80.2%) | 0.301 |

| LIMA | 28 (66.7%) | 46 (58.2%) | 0.365 |

| RIMA | 4 (9.8%) | 3 (3.7%) | 0.175 |

| Operation time | 245.8 ± 75.9 | 216.7 ± 82.0 | 0.122 |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | 34.3 ± 14.2 | 32.4 ± 15.9 | 0.534 |

| Duration of therapy | 25.7 ± 19.4 | 26.1 ± 18.0 | 0.93 |

| Mortality | 6 (14.0%) | 5 (6.2%) | 0.147 |

BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LIMA: left internal mammary artery; RIMA: right internal mammary artery.

Pathogens and antibiotic therapy

The majority of tissue cultures from mediastinitis patients showed Staphylococcus aureus (64 patients, 51.6%) or coagulase-negative Staphylococcus strains (28 patients, 22.6%). Eight (6.5%) patients had Enterococcus faecalis, 7 (5.6%) patients had Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 4 (3.2%) patients had Serratia marcescens, 3 (2.4%) patients had Proteus mirabilis and 3 (2.4%) patients had Enterococcus faecium. Enterobacter aerogenes, Morganella morganii and Escherichia coli were found as primary pathogens in a smaller amount of patients. In 4 (3.2%) patients, the tissue cultures remained negative, most likely due to prior antibiotic treatment. Infections with more than one pathogen occurred in 13 patients. The mean duration of antibiotic treatment was 33.1 ± 15.3 days.

Outcome

The primary results of the Redon treatment are presented in Table 4.

Table 4:

Primary outcomes

| Patients, n = 124 | |

|---|---|

| Intensive care unit staya | 6.2 ± 11.0 |

| Length of antibiotic treatmenta | 33.1 ± 15.3 |

| Length of treatmenta | 25.9 ± 18.4 |

| Treatment failure | 10 (8.1%) |

| Mortality | 11 (8.9%) |

| Length of staya,b | 32.8 ± 20.7 |

aTime in days.

bAfter diagnosis of post-sternotomy mediastinitis.

In 10 patients treatment modality changed during hospital stay. In those patients, there was a need for a resternotomy because of additional cardiac surgery for endocarditis or treatment failure, defined as increasing infection parameters due to recurrent or ongoing mediastinitis. In these cases, the treatment for mediastinitis was continued using VAC therapy. This treatment was successful in all patients. Univariate analysis revealed no risk factors for treatment failure.

Of the 124 patients, 11 (8.9%) died during treatment for post-sternotomy mediastinitis. Cause of death was mostly multiorgan failure (4 patients), renal failure (2 patients) or respiratory failure (2 patients). Other causes of death were bleeding (2 patients) or cardiac failure (1 patient). Univariate analysis for pre-, peri- or postoperative factors revealed no specific risk factors for mortality.

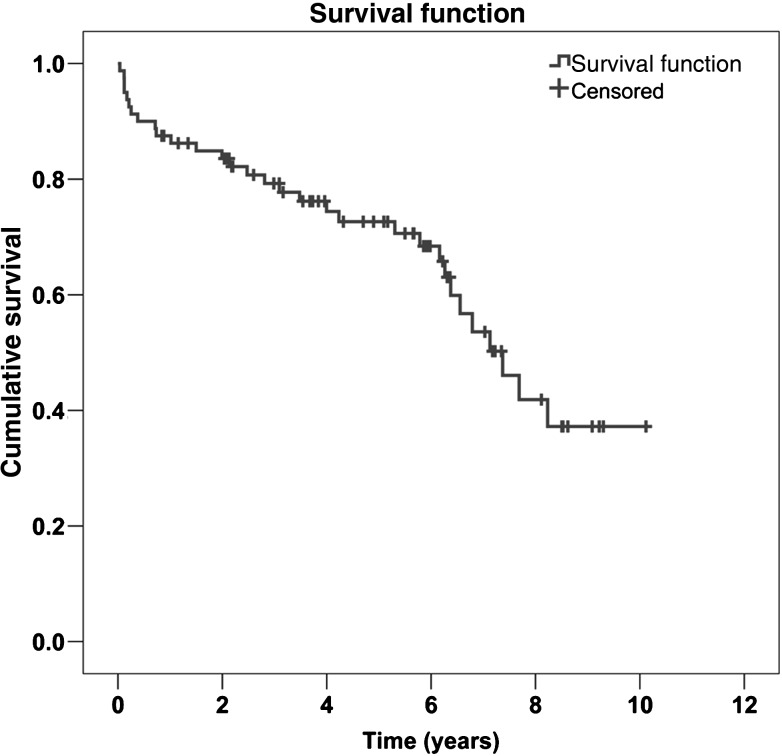

C-reactive protein and leucocytes count

C-reactive protein levels and blood leucocyte counts declined significantly between the moment of diagnosis of mediastinitis (t0) and t3 (14–21 days after t0) (Fig. 2A and B) (P-value of C-reactive protein declination: <0.001, P-value of leucocyte count declination: <0.001). C-reactive protein levels decreased with 8.77 mg l−1 d−1. Leucocytes decreased with 0.4 × 109 l−1 d−1.

Figure 2:

C-reactive protein (A) and leucocyte course (B). t0: diagnosis of mediastinitis, t1: 3–7 days after t0, t2: 8–13 days after t0, t3: 14–21 days after t0. Error bars show SDs.

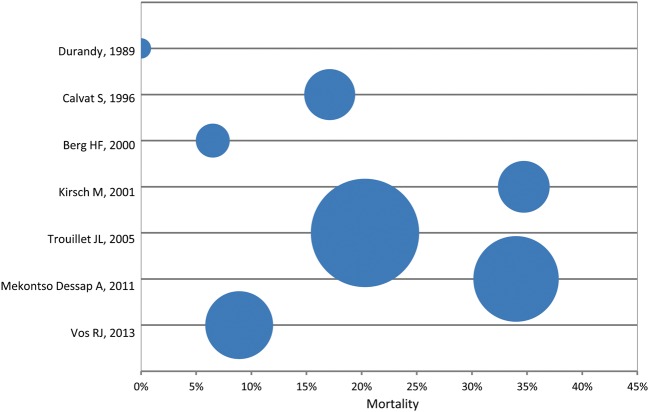

Long-term survival

There was 6.4% loss to follow-up. The median follow-up time was 6.6 years. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve of long-term survival. The 1- and 5-year survival was 86 and 70%, respectively. None of the deaths of patients after hospital discharge were due to mediastinitis-related problems.

Figure 3:

Kaplan–Meier curve of the long-term survival.

DISCUSSION

Post-sternotomy mediastinitis is a serious complication of open heart surgery, and during the last decades several treatment modalities have been described. Using Redon therapy in 124 patients, we report a mean length of stay of 32 days and mortality of nine percent. The incidence of post-sternotomy mediastinitis in our study population was low (0.71%) compared with that in the literature (usually 1–3%) [1]. Most patients were infected with S. aureus or coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. These bacteria are commonly found pathogens in post-sternotomy mediastinitis [1]. The interval between the initial cardiac operation and reoperation for mediastinitis was 15 days, which is in line with earlier reports [2, 3]. After reoperation for mediastinitis and placement of Redon drains, patients stayed on intensive care unit (ICU) for a mean of 6 days. This is remarkably shorter compared with the mean ICU stay of 29 days reported by Calvat et al. [10] and Trouillet et al. [ 13]. Noticeably both studies originated from the same department, which although not clearly delineated seems to have the custom of attending patients on the ICU until all drains are removed. We maintain a policy of transferring patients to the postoperative ward when they require no inotropic or respiratory support, probably thus reducing costs. The feasibility and safety of this approach are supported by data from the group of Kirsch et al. [12], which reported the need for postoperative surveillance in an ICU for 69% of the Redon-treated patients with an average stay of 10 days.

The technique of Redon drainage is adapted from orthopaedic surgery where it is used as the treatment for osteomyelitis of long bones [8]. Like VAC, Redon drains are presumed to increase the drainage of infected fluids and reduce the residual cavity, thereby promoting wound healing. Indeed, Berg et al. [9] reported a significant shorter length of stay using Redon drainage when compared with continuous irrigation. We report a total length of hospital stay of 32 days, which is comparable with previously reported data. The technique of Redon drainage was similar in both hospitals. The antibiotics policy was different in both centres. In Amphia Hospital, Breda, antibiotic therapy was switched from intravenously to per os after removal of Redon drains, resulting in a shorter duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy. Despite this, total duration of antibiotic treatment was comparable in both hospitals (Table 3).

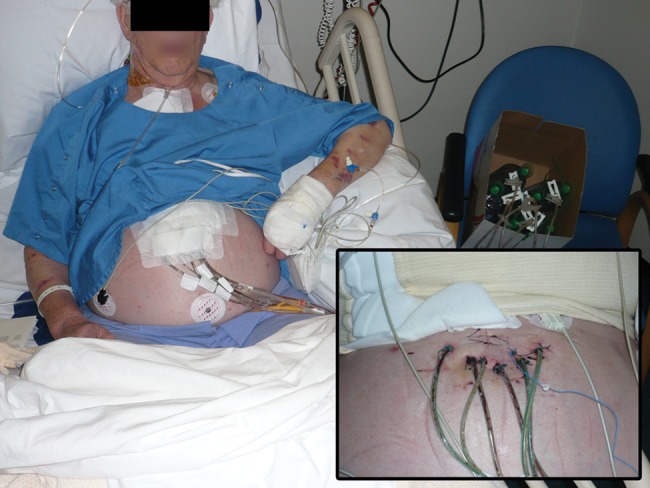

Since the introduction of Redon drainage for post-sternotomy mediastinitis in 1989, five studies described the results of this treatment modality. The mortality rates of those studies varied between 6.5 and 34.7% [9–13]. Figure 4 shows a bubble diagram illustrating the mortality rates of those studies. Kirsch et al. [12] in 2001 and Mekontso Dessap et al. [11] in 2011 reported relatively high mortality rates of 34.7 and 34%, respectively. Both studies were performed in the same department. Preoperative risk factors were comparable with our study population. However, the technique of Redon drainage was slightly different. In their patient populations, catheters were progressively removed after 10 days of closed drainage (2 cm daily). This resulted in a drainage duration of 15.8 ± 6.0 days and 15.5 ± 7 days, respectively [11, 12]. In our study, the effluence from each Redon bottle was cultured once every 3 days. The corresponding drain was removed when at least two consecutive cultures were negative. This resulted in a longer drainage duration of 25.9 ± 18.4 days, but might have contributed to a lower mortality rate of 8.9%.

Figure 4:

Bubble diagram showing mortality rates of studies done using primary closure with Redon drains as a sole therapy for post-sternotomy mediastinitis. Size of bubble indicates number of patients included in the study.

The greater part of the deaths of the patients in hospital were a consequence of sepsis followed by multi organ failure. This is a well-known cause of death during the treatment of post-sternotomy mediastinitis and is seen in all different treatment modalities (open packing, VAC therapy, Redon therapy) [3, 4, 11].

No patients died as a consequence of mediastinal infections after discharge. One and 5-year survivals were 86 and 70%, respectively. Those rates are comparable with recently published long-term results after treatment for post-sternotomy mediastinitis [15, 16].

A frequently used therapy for post-sternotomy mediastinitis is VAC. Results of this treatment have been described several times in the past years [2–6]. Reported mortality rates in VAC treated mediastinitis range from 0 to 28.6%, which make them comparable with the mortality rate observed in our study. Closed drainage using Redon drains comes with a number of benefits. Primary closure of the sternum provides healing without repeated intervention and may therefore be more comfortable for patients than VAC therapy, where the VAC sponges have to be replaced several times during the treatment period. Adverse events like right ventricular bleeding can occur during VAC treatment [7]. Such complications are not described using Redon therapy. Severe complications such as right ventricular or venous graft bleeding were not observed in our study population. There are no randomized controlled trials in which those two treatment modalities are prospectively compared. Therefore, further research is needed to compare VAC with Redon treatment.

Selection bias may have played a role in our study. In both hospitals not all patients with post-sternotomy mediastinitis were treated with Redon drainage. The treatment modality used was decided by the operating surgeon. Wound depth, size of wound bed and the viability of the sternum could influence the surgeons' decision. These factors are not included in our or previously published studies. Randomized trials comparing VAC and Redon treatment are needed to evaluate contraindications regarding both treatment methods.

Conclusions

In our selected population primary closure of the sternum over Redon drains was safe and efficacious compared with previously published data regarding VAC treated mediastinitis. The technique is simple, and the length of in-hospital stay and mortality rate are acceptable. Further research is necessary to directly compare Redon drainage with VAC treatment for post-sternotomy mediastinitis.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sjögren J, Malmsjö M, Gustafsson R, Ingemansson R. Poststernotomy mediastinitis: a review of conventional surgical treatments, vacuum-assisted closure therapy and presentation of the Lund University Hospital mediastinitis algorithm. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjögren J, Gustafsson R, Nilsson J, Malmsjö M, Ingemansson R. Clinical outcome after poststernotomy mediastinitis: vacuum-assisted closure versus conventional treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:2049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs U, Zittermann A, Stuettgen B, Groening A, Minami K, Koerfer R. Clinical outcome of patients with deep sternal wound infection managed by vacuum-assisted closure compared to conventional therapy with open packing: a retrospective analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luckraz H, Murphy F, Bryant S, Charman SC, Ritchie AJ. Vacuum-assisted closure as a treatment modality for infections after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:301–5. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song DH, Wu LC, Lohman RF, Gottlieb LJ, Franczyk M. Vacuum assisted closure for the treatment of sternal wounds: the bridge between débridement and definitive closure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:92–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000037686.14278.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doss M, Martens S, Wood JP, Wolff JD, Baier C, Moritz A. Vacuum-assisted suction drainage versus conventional treatment in the management of poststernotomy osteomyelitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:934–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sartipy U, Lockowandt U, Gäbel J, Jidéus L, Dellgren G. Cardiac rupture during vacuum-assisted closure therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1110–1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durandy Y, Batisse A, Bourel P, Dibie A, Lemoine G, Lecompte Y. Mediastinal infection after cardiac operation. A simple closed technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:282–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg HF, Brands WG, van Geldorp TR, Kluytmans-VandenBergh FQ, Kluytmans JA. Comparison between closed drainage techniques for the treatment of postoperative mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:924–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvat S, Trouillet JL, Nataf P, Vuagnat A, Chastre J, Gibert C. Closed drainage using Redon catheters for local treatment of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mekontso Dessap A, Vivier E, Girou E, Brun-Buisson C, Kirsch M. Effect of time to onset on clinical features and prognosis of post-sternotomy mediastinitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:292–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirsch M, Mekontso-Dessap A, Houël R, Giroud E, Hillion ML, Loisance DY. Closed drainage using Redon catheters for poststernotomy mediastinitis: results and risk factors for adverse outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1580–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trouillet JL, Vuagnat A, Combes A, Bors V, Chastre J, Gandjbakhch I, et al. Acute poststernotomy mediastinitis managed with debridement and closed-drainage aspiration: factors associated with death in the intensive care unit. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:518–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20:271–4. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(05)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risnes I, Abdelnoor M, Almdahl SM, Svennevig JL. Mediastinitis after coronary artery bypass grafting risk factors and long-term survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1502–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins BZ, Onaitis MW, Hutcheson KA, Kaye K, Petersen RP, Wolfe WG. Does method of sternal repair influence long-term outcome of postoperative mediastinitis? Am J Surg. 2011;202:565–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]