Abstract

Neuropeptides play central roles in the regulation of homeostatic behaviors such as sleep and feeding. Caenorhabditis elegans displays sleep-like quiescence of locomotion and feeding during a larval transition stage called lethargus and feeds during active larval and adult stages. Here we show that the neuropeptide NLP-22 is a regulator of Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like quiescence observed during lethargus. nlp-22 shows cyclical mRNA expression in synchrony with lethargus; it is regulated by LIN-42, an orthologue of the core circadian protein PERIOD; and it is expressed solely in the two RIA interneurons. nlp-22 and the RIA interneurons are required for normal lethargus quiescence, and forced expression of nlp-22 during active stages causes anachronistic locomotion and feeding quiescence. Optogenetic stimulation of RIA interneurons has a movement-promoting effect, demonstrating functional complexity in a single neuron type. Our work defines a quiescence-regulating role for NLP-22 and expands our knowledge of the neural circuitry controlling Caenorhabditis elegans behavioral quiescence.

Introduction

Neuropeptides are central to mechanisms by which biological clocks temporally align animal behavior with recurring internal or external conditions. In mammals, the neuropeptide hypocretin/orexin is secreted from lateral hypothalamic neurons to promote wakefulness during the optimal time of day for foraging1. Other mammalian neuropeptides shown or proposed to regulate behavioral outputs of circadian clocks include prokineticin 2, epidermal growth factor (EGF)3, neuropeptide S4, prolactin-releasing peptide5, urotensin II6, and neuromedin S7. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor (PDF) is released from central nervous system circadian neurons to control sleep/wake behavior8–10, emphasizing a conserved role for neuropeptides in translating clock information to behavior8.

In Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), sleep-like behavior is observed during lethargus periods, which occur at transitions between each of the four larval stages and between the fourth larval stage and the adult stage11. During lethargus, animals cease locomotion, feeding, and foraging, are less responsive to stimuli, and display a homeostatic response to forced movement12, 13. Signaling pathways involving cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), EGF, and pigment dispersing factor (PDF), which play roles in the regulation of mammalian and/or Drosophila sleep, also function in the regulation of C. elegans sleep-like quiescence12, 14, 15, suggesting that C. elegans quiescence has fundamental similarities to sleep in other animals. Additional molecular similarity between quiescence during lethargus and mammalian sleep is demonstrated by the larval cycling of expression of the protein LIN-42, which is homologous to the core circadian protein PERIOD16. lin-42 is required for proper timing of lethargus17, much as period is required for proper timing of circadian sleep18, but mechanisms by which lin-42 may affect quiescent behavior were previously unknown.

Here we identify the gene nlp-22 as a lin-42-regulated gene affecting quiescent behavior. nlp-22 encodes a neuropeptide, whose function and expression were previously unknown. We show that nlp-22 can induce quiescence in normally active animals and is necessary for normal lethargus quiescence. In addition, we present evidence of a surprising functional complexity of neurons expressing NLP-22. Our findings expand our knowledge of the neural circuitry controlling C. elegans behavioral quiescence.

Results

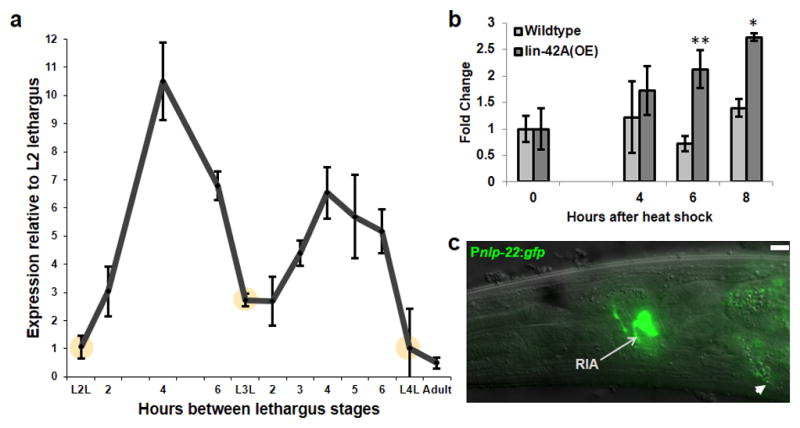

nlp-22 expression cycles in response to a larval clock

The activity of many mammalian neuropeptides with roles in clock regulation is controlled at the level of mRNA abundance. We therefore reasoned that a somnogenic peptide controlled by the larval clock would be up-regulated before or during lethargus. We performed a transcriptional profiling experiment (manuscript in preparation) in precisely-staged animals to identify genes with elevated expression before or during the fourth lethargus stage. mRNA abundance of the gene nlp-22, which encodes a protein predicted to be processed into a neuropeptide19, was higher in the L4 stage than in lethargus. Using qRT-PCR we confirmed that nlp-22 mRNA cycles expression with a constant phase relationship to lethargus (Fig. 1a). nlp-22 mRNA peaked midway through the active larval stages, decreased during each lethargus stage, and was absent in adults.

FIGURE 1.

nlp-22 is expressed in dynamic fashion in the RIA interneurons. (a) mRNA expression during larval development. Expression levels cycle in synchrony with each lethargus stage. Yellow circles depict each lethargus stage, as defined by cessation of feeding of the animals (Biological replicates per time point ≥3, technical replicates = 2 for each biological replicate; Error bars represent s.e.m.). (b) nlp-22 expression is increased in response to lin-42 over-expression during the adult stage. (*p<0.05, ** p<0.005, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, Biological replicates per condition ≥5, technical replicates = 2 for each biological replicate; Error bars represent s.e.m.). (c) An nlp-22 transcriptional GFP reporter is expressed in the RIA neurons (arrow). Intestinal auto-fluorescence is also observed (arrow head). Scale Bar = 5μM.

Given the cyclical nature of nlp-22 expression, we hypothesized that NLP-22 signaling is regulated by the larval clock. The C. elegans ortholog of the core circadian regulator PERIOD is LIN-42, which is required for synchronization of lethargus quiescence and molting16, 17. Like PERIOD, which shows cyclical expression with a circadian periodicity in insects and mammals20, LIN-42 shows cyclical expression with larval periodicity in C. elegans16, 21. LIN-42 expression has a similar phase relationship to lethargus as NLP-22. We found that LIN-42A anachronistic over-expression induced an increase in nlp-22 mRNA (Fig. 1b), suggesting that nlp-22 transcription is down-stream of a larval lin-42 based clock.

nlp-22 is expressed in the pair of RIA interneurons

To determine where nlp-22 is expressed, we generated a transcriptional reporter by placing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of nlp-22 regulatory DNA. We observed expression only in one pair of head neurons, which we identified as the RIA interneurons, based on process morphology and comparison to expression of the previously characterized gene glr-3 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S1a). Thus, nlp-22 expression is cyclical and restricted to the RIA neurons.

NLP-22 is predicted to be secreted19. Secreted proteins in C. elegans, when fused to a fluorescent moiety on their C-terminus, can be visualized in cells outside of the cells in which they are expressed22. When we fused GFP to the C-terminus of the NLP-22 preproprotein, we observed green fluorescence in several neurons in the head as well as the ventral nerve cord (Supplementary Fig. S1b), supporting the notion that NLP-22 is a secreted peptide. When we fused GFP to the N-terminus of the NLP-22 preproprotein, expression was exclusively in the RIA neurons, presumably because the GFP protein interfered with the functionality of the signal sequence (Supplementary Fig. S1c). Thus, our data indicates that the NLP-22 peptide is processed and secreted from the RIA interneurons and may be acting by synaptic and/or neuroendocrine mechanisms.

NLP-22 induces behavioral quiescence

Based on the observation that nlp-22 mRNA cycles expression during larval development in phase with the cycling of sleep-like behavior, we hypothesized that it regulates lethargus quiescence. To test this hypothesis, we genetically manipulated nlp-22 expression and observed the effects on quiescence and active behavior.

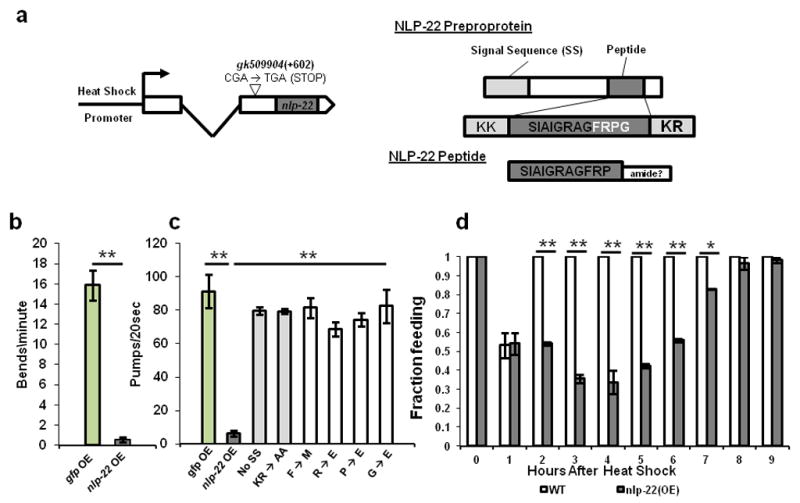

We first studied the effect of temporal and spatial mis-expression of nlp-22 during the adult stage, when the animals are typically feeding and moving. C. elegans moves by making dorsal and ventral body bends initiated at the anterior end of the animal23 and feeds by rhythmic pharyngeal contractions called pumps24. When we over-expressed nlp-22 using an inducible heat-shock promoter (Fig. 2a) during the normally active adult period, we observed quiescence of feeding and locomotion (Fig. 2b,c, Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Table S1). Two hours after heat shock, control animals made 15.9 ± 7.3 ( all values presented as mean ± s.d.)(N=15) anterior body bends per minute whereas animals over-expressing nlp-22 made 0.55 ± 1.1(N=25) body bends per minute (Fig. 2b). Wild-type animals and transgenic control animals expressing GFP under the control of a heat shock promoter pumped two hours after heat shock at rates of 264.9 ± 17.4(N=20) and 273.6 ± 17.5(N=20) pumps per minute, respectively (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table S1). Animals carrying the integrated or extrachromosomal Phsp16.2:nlp-22 arrays, qnIs142 or qnEx95, pumped at rates of 18.6 ± 31.1(N=37) and 25.2 ± 32.3(N=40) per minute, respectively, two hours after heat shock (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table S1). In the absence of either the signal sequence or the dibasic residues predicted to be necessary for preproprotein cleavage25, nlp-22 over-expression no longer promoted behavioral quiescence (Fig. 2c), indicating that these features of the protein are important for its biological activity. When we mutated any of the four C-terminal amino acids of the predicted peptide, over-expression of the gene no longer caused quiescence (Fig. 2c), indicating that these four amino acids are important for the peptide’s biological function. Nine hours after nlp-22 over-expression, all the animals resumed feeding, indicating that the reduction in behavior was not due to an injurious effect (Fig 2d).

FIGURE 2.

NLP-22 induces behavioral quiescence. (a) Gene and protein structure of nlp-22 including over-expression construct. 2.5 hours after nlp-22 induction, animals show reduced movement (b) and feeding (c) relative to control animals over-expressing GFP (strain: TJ375). (c) Removing the signal sequence, or mutating the KR or FRPG eliminates the ability of NLP-22 to reduce pumping rate (**p<0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, N≥20). (d) Animals over-expressing nlp-22 cease pumping, but recover 9 hours after heat-shock (*p<0.001, **p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test, N≥20 animals, 2 trials; Error bars represent s.e.m.).

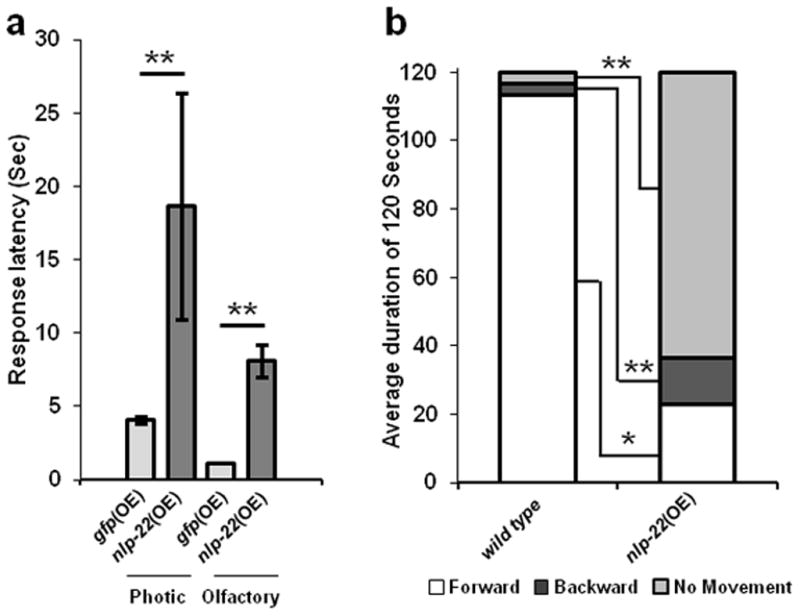

NLP-22-induced quiescence resembles lethargus quiescence

During lethargus, animals are less responsive to stimuli, a property shared with sleeping vertebrates12. In addition, worms in lethargus move backwards more often than non-lethargus worms26. Like wild-type worms in lethargus, adult worms over-expressing nlp-22 showed reduced responsiveness to optic or chemical stimulation compared to transgenic control animals that over-expressed GFP (Fig. 3a). Under mild heat shock conditions, in which nlp-22 over-expressing adult animals were not completely quiescent, they moved backwards more often than control animals (Fig. 3b). Thus, over-expression of NLP-22 induces feeding and movement quiescence that is reminiscent of lethargus quiescence.

FIGURE 3.

Quiescence induced by nlp-22 OE resembles lethargus quiescence. (a) Animals that over-express nlp-22 (strain: NQ251) are less responsive to chemical (1-octanol) and optical (blue light) stimulation than control animals that over-express GFP (strain: TJ375) (**p<0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, N≥20; Error bars represent s.e.m.). (b) Over-expressing nlp-22 via a mild heat shock, such that full quiescence is not induced, results in increased backwards movement. White, dark gray, and light gray denote forward, backwards, and no movement, respectively. The average fraction of time spent moving forward or moving backward in a 120s window for nlp-22 over-expressing animals is significantly different from WT worms (*p<0.001. **p<0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, N=20). In addition to the bias for backwards motion, nlp-22 over-expressing animals also moved significantly less than WT animals (**p<0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, N=20).

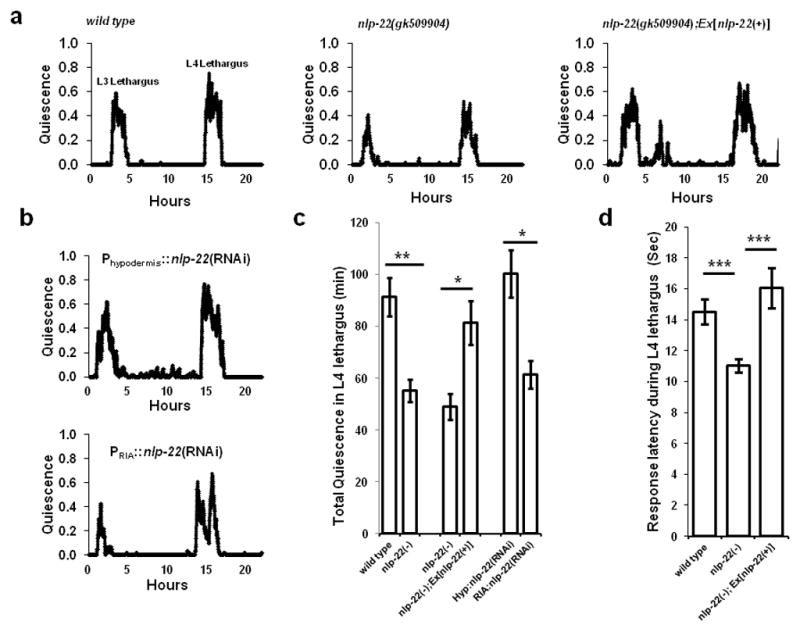

NLP-22 is required for proper quiescence during lethargus

Our over-expression studies demonstrate sufficiency of nlp-22 for the induction of behavioral quiescence. However, over-expression experiments are likely to result in supra-physiological concentrations of the peptide as well as spatially ectopic expression. Therefore, we proceeded to study a loss of function nlp-22 mutation in order to ask the question: Is nlp-22 necessary for quiescence? The nlp-22 allele gk509904 has a point mutation that introduces a stop codon prior to the NLP-22 peptide (Fig. 2a); thus, it is likely to fully eliminate nlp-22 function. We measured quiescence in wild-type and nlp-22(gk509904) animals from the active L3 stage through development into adulthood. Total quiescence during L4 lethargus of gk509904 mutants was reduced in comparison to total quiescence of wild-type animals (Fig. 4a,c and Supplementary Table S2). The quiescence defect of gk509904 mutants was rescued by expression of a genomic fragment spanning the nlp-22 locus (Fig. 4a,c and Supplementary Table S2). To test for the functional relevance of the observed RIA gene reporter expression, we expressed nlp-22 double stranded RNA (dsRNA) to knockdown nlp-22 mRNA specifically in RIA, and, as a control, in the hypodermis. Expression in the RIA neurons but not in the hypodermis reduced lethargus quiescence (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Table S2). In addition to reduced quiescence, nlp-22(gk509904) mutants showed enhanced responsiveness to optic sensory stimulation during L4 lethargus quiescence bouts (Fig. 4d), demonstrating reduced sleep-like behavior. Thus, nlp-22 is required for appropriate C. elegans sleep-like quiescence during lethargus.

FIGURE 4.

nlp-22 is required for normal quiescence during lethargus. (a) Fraction of quiescence in a 10-minute moving window in a wild-type animal, an nlp-22(gk509904) mutant, and an nlp-22(gk509904) mutant carrying an nlp-22 genomic rescuing transgene. The x-axis is hours from the start of recording in the late third larval stage. (b) Quiescence in animals expressing double stranded nlp-22 RNA in the hypodermis and in the RIA neurons. Average quiescence (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test; N≥10, Error bars represent s.e.m.), (c) and response latencies to blue light (d) during fourth larval stage lethargus (***p<0.001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test; N≥28 animals, Error bars represent s.e.m.).

NLP-22 signals through a PKA-dependent mechanism

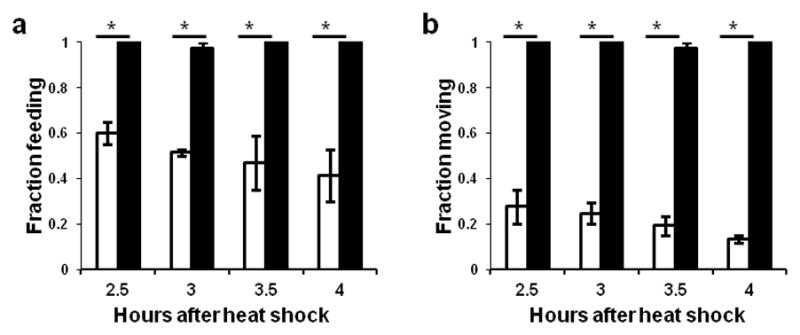

To determine mechanisms by which nlp-22 induces sleep-like behavior, we crossed animals carrying nlp-22 over-expression arrays into a subset of the genetic backgrounds that have been previously shown to affect C. elegans quiescence (kin-227, egl-412 and ceh-1714) and into genetic backgrounds known to affect neuropeptide processing or release (egl-328, egl-2129 and unc-3130) (Supplementary Table S1). In all cases but one, the quiescence-inducing effects of nlp-22 over-expression were no different in the mutant background from these effects in the wild-type background. The one observed exception was in kin-2(ce179) mutants, in which the normal inhibition of the catalytic subunits of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase PKA by the regulatory subunits is impaired due to a mutation in the regulatory subunit, resulting in excess activity of the catalytic subunit31. Excessive PKA activity causes increased wakefulness in C. elegans and other species32. kin-2 mutants are hyperactive33, are hyper-responsive to stimuli during lethargus, and show reduced lethargus quiescence27. In the kin-2 mutant background Phsp16.2:nlp-22 transgenic animals continued to feed and move from 2.5 to 4.0 hours after heat shock (Fig. 5a,b). Thus, a reduction in PKA activity is required for NLP-22-induced quiescence. Though kin-2 mutants continued to pump upon nlp-22 over-expression, pumping rates were reduced relative to kin-2 mutant controls (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that either residual kin-2 activity in the mutant analyzed is sufficient to reduce PKA activity in response to nlp-22 over-expression, or that there are also PKA-independent pathways regulating feeding and locomotion quiescence in response to nlp-22.

FIGURE 5.

NLP-22-induced quiescence requires the protein kinase A subunit KIN-2. Feeding (a) and locomotion (b) quiescence induced by nlp-22 over-expression is impaired in kin-2 mutants (*p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test, N>20 animals, 2 trials; Error bars represent s.e.m.). Unfilled bars represent animals of genotype qnIs142[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22; Phsp-16.2:gfp; Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)] and filled bars represent animals of genotype qnIs142; kin-2(ce179)X.

The RIAs have quiescence- and movement-promoting properties

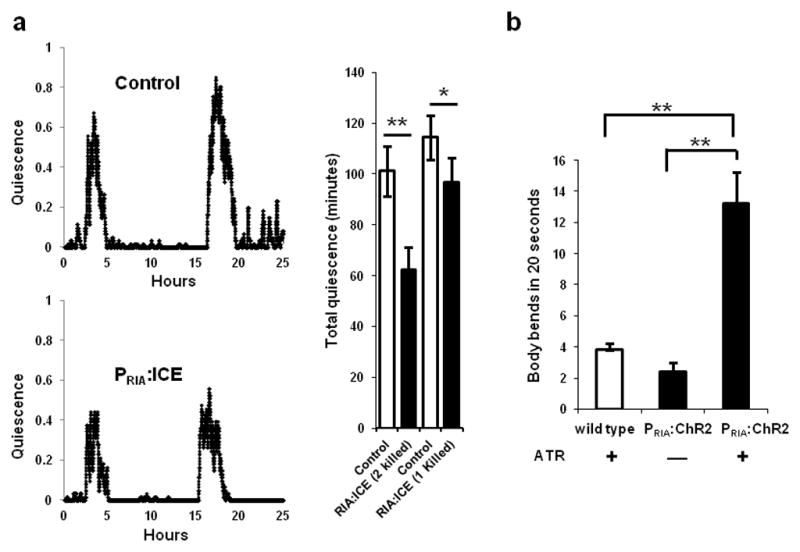

Because the RIA neurons express the somnogenic peptide NLP-22, we hypothesized that they are quiescence-promoting neurons. To test this hypothesis, we used the strain VM1345, which expresses the cell death gene Interleukin-lβ-Converting Enzyme (ICE)34–36 in the RIA neurons. Because of the incomplete penetrance of the RIA ablation phenotype in VM1345, in a subset of the animals only one of the two RIAs died. We compared L4 lethargus quiescence in animals lacking one or two RIAs to a control transgenic strain with both RIA neurons intact. There was a significant reduction in lethargus quiescence in animals lacking both RIA neurons (Fig. 6a), consistent with the hypothesis that RIA neurons promote quiescence. Animals lacking only one of the RIA neurons also showed a small but significant reduction in L4 lethargus quiescence compared to control transgenic animals (Fig 6a).

FIGURE 6.

The RIA neurons have both quiescence- and movement-promoting functions. (a) Genetic ablation of the RIA interneurons using the cell death protein ICE (strain:VM1345) decreases quiescence during lethargus compared to control transgenic animals (strain: NQ156). The traces depict the fraction of quiescence in a 10 minute time interval. The top trace is of a control animal of genotype lin-15(n765ts)X; qnEx48[Pins-4:gfp:PEST; lin-15(+)], and the bottom trace is of an experimental animal of genotype lin-15(n765ts)X; akEx211[Pglr-3:gfp; Pglr-3:ICE; lin-15(+)]. Total quiescence during L4 lethargus is lower in experimental animals lacking either one or both RIA neurons than in control animals to which they were paired (*p<0.05, **p<0.001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, N≥9; Error bars represent s.e.m.). (b) Optogenetic stimulation of the RIA neurons promotes movement during lethargus. WT animals grown on All Trans Retinal (ATR) and PRIA:ChR2 worms grown either in the absence or presence of ATR, were identified as they entered L4 lethargus, transferred to a new plate and were unperturbed for 15 minutes until they became quiescent. Body bends were counted for one minute after a 15-second exposure of quiescent animals to blue light. PRIA:ChR2 animals on ATR moved significantly more than control animals (*p<0.05, **p<0.001, Student’s two-tailed t-Test, WT (N=15), No ATR vs. ATR (N≥20); Error bars represent s.e.m.).

This neuron ablation experiment supports the notion that the RIA neurons promote sleep-like behavior. However, removing the neuron by genetic ablation is a chronic manipulation that removes all functions of the neurons, including both those related to rapid signaling via membrane voltage changes as well as chronic signaling via mechanisms independent of membrane voltage. To test whether acute depolarization of the RIA neurons also induces quiescence, we made transgenic animals expressing the blue light-activated cation channel channelrhosopsin-2 (ChR2)37 in the RIA neurons. We optogenetically depolarized the RIA neurons during the active L4 stage as well as during L4 lethargus. Animals carrying the ChR2 transgene in the RIA neurons were cultivated in the absence (N=4) or presence (N=7) of the ChR2 co-factor all-trans retinal (ATR) and followed for eight hours during the active L4 stage. The animals were exposed to blue light for 15 seconds every 30 minutes and monitored for locomotion and feeding quiescence. Stimulating the RIA neurons during the active L4 stage caused no induction of behavioral quiescence. In contrast, optogenetic depolarization of the RIA neurons during L4 lethargus had a locomotion-stimulating effect. Compared to control animals lacking the ChR2 transgene and to control animals carrying the transgene but lacking ATR, stimulation of the RIA neurons increased movement during lethargus (Fig. 6b). Thus, acute depolarization of the RIA neurons during lethargus promotes wake-like behavior.

We conclude that the RIA neurons have both quiescence-promoting effects, revealed by chronic ablation, and wake-promoting effects, revealed by acute depolarization. Thus, the RIA neurons are complex regulators of lethargus quiescence with both movement- and quiescence-promoting roles.

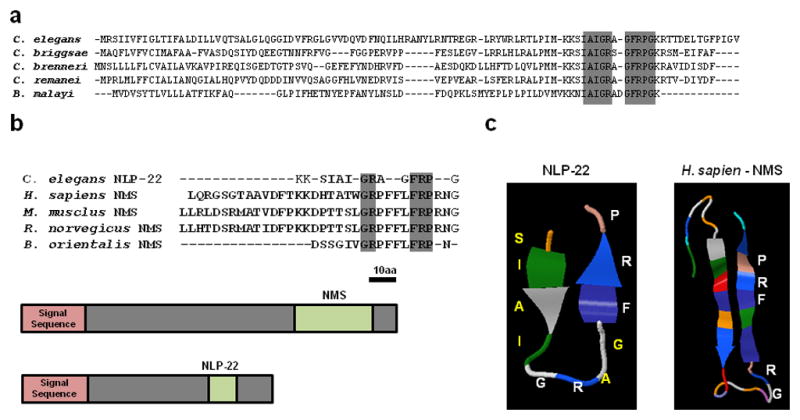

NLP-22 is structurally similar to mammalian Neuromedin S

The NLP-22 predicted peptide has a glycine at its C-terminus. In prior analyses, C. elegans neuropeptides with a C-terminal glycine have been shown to be deglycinated and then amidated during peptide maturation38. Hence, NLP-22 has been termed an FRPamide peptide, corresponding to a Phenylalanine(F)-Arginine(R)-Proline(P) motif19 (Fig. 2a). Using the alignment program Muscle (version 3.7)39 on the Phylemon 2.0 platform40, we found that the predicted NLP-22 neuropeptide in C. elegans is nearly identical to orthologous proteins of four other nematodes (Fig. 8a), indicating strong functional selection on the neuropeptide sequence. Comparing the NLP-22 neuropeptide with human neuropeptides, we noted similarities with neuromedin S (NMS). Both the NLP-22 and NMS peptides are located near the C-terminus of the preproprotein (Fig. 8b) and are composed of the dipeptide Glycine(G)-Arginine(R) located in the middle of the peptide and the tripeptide FRP located at or close to the C-terminus (Fig. 8b).

FIGURE 8.

NLP-22 is similar to Neuromedin S. (a) Alignment of NLP-22 preproprotein with orthologs from four nematode species. High conservation (gray box) is observed in the predicted neuropeptide sequence. (b) Amino acid sequence similarities (gray boxes) between NLP-22 and vertebrate Neuromedin S peptides. The preproprotein structure of human Neuromedin S and NLP-22 is also shown. Each has an N-terminal signal sequence and a single, c-terminal peptide. The preproprotein is drawn to scale (Bar = 10 Amino Acids) (c) Predicted structures of NLP-22 and of NMS. The conserved GR dipeptide and FRP tripeptide motifs are shown in white.

To further compare NLP-22 to NMS, we used the peptide structure algorithm Pep-Fold41 which predicts the three-dimensional structures of small peptides. Pep-Fold predicts that NLP-22 forms an anti-parallel beta-sheet where the conserved GR dipeptide is within the loop and the C-terminal FRP is near the end of the second sheet (Fig. 8c). Interestingly, human NMS is predicted to form the same general structure (Fig. 8c). These structural similarities suggest that NLP-22 and NMS may be orthologous peptides.

Discussion

Wake-promoting neuropeptides such as hypocretin/orexin in vertebrates and PDF in Drosophila have well-defined roles as modulators of sleep/wake as an output of the circadian clock9. However, few physiologically-relevant sleep-promoting peptides have been identified3, 5, 42 and their relationship to the circadian clock is poorly understood. We have identified NLP-22 as a C. elegans somnogenic peptide. NLP-22 activity is partially regulated at the level of mRNA abundance in response to a LIN-42/PER-based larval clock, suggesting that similar somnogens may function as the output to the PER-based circadian clock in other species.

How might LIN-42 be regulating nlp-22 expression? Drosophila PER acts as a cell-autonomous negative regulator of transcription of genes that are positively regulated by the transcription factors CLK and CYC20. In response to ectopic expression of LIN-42, we observed nlp-22 mRNA induction only after 6–8 hours, which is delayed relative to a typical heat shock response43. If LIN-42 were functioning in C. elegans similarly to PER function in Drosophila, then LIN-42 could repress transcription of a gene that negatively regulates nlp-22 expression in the same cell. Alternatively, the interaction could be non-cell-autonomous. In support of a possible non-cell-autonomous interaction, restoration of LIN-42 in the hypodermis of lin-42 mutants partially rescues the asynchronous nature of lethargus quiescence17 yet nlp-22 is expressed outside the hypodermis, in the RIA interneurons. Even if LIN-42 were regulating nlp-22 expression directly, then it must also regulate other genes, since nlp-22 mutants do not show other phenotypes observed for lin-42 mutants such as heterochronic defects, slow growth, and molting defects17, 44.

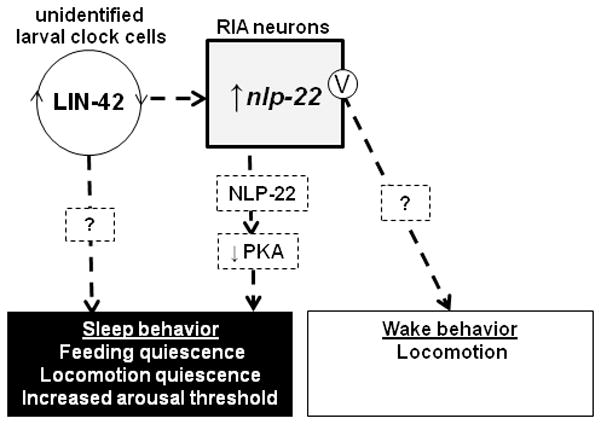

What is the role of the RIA interneurons during lethargus quiescence? The RIAs are a highly connected pair of interneurons that are required for thermotaxis45 and aversive/associative learning35, 46–48. Our data suggests that the RIAs also control sleep-like behavior. Surprisingly, our experiments revealed both quiescence- and movement-promoting functions for the RIA neurons. Our results suggest that the RIAs release two factors with different behavioral effects: the neuropeptide NLP-22, which decreases PKA activity in an unidentified cell type (Fig. 7) to promote quiescent behavior; and an unknown transmitter, which promotes movement. Since acute depolarization of RIA promotes movement and not quiescence, the mechanism of NLP-22 release may be different from that of the movement-promoting transmitter. NLP-22 release may be regulated by second messengers independently from the membrane voltage. For example, a local calcium increase without membrane potential change could promote NLP-22 secretion without affecting release of wake-promoting factor. Consistent with this possibility, the RIA neurons show sub-cellular compartmentalization of intracellular calcium levels49. In addition, NLP-22 availability is regulated at least partially at the level of mRNA abundance. Regardless of the explanation for these results, they highlight both the limitation of relying on ablation alone to infer neuron function and the benefit of using acute optogenetic activation to understand neuronal function.

FIGURE 7.

Model for role of nlp-22 and RIA in sleep-like quiescence regulation. LIN-42 functions in as yet unidentified larval clock cells to regulate nlp-22 expression as well as other quiescence-regulatory factors. Release of NLP-22 neuropeptide promotes sleep-like behavior via a reduction of protein kinase A (PKA) activity. RIA membrane depolarization (marked with the letter V) results in the release of an unidentified wake-promoting neurotransmitter.

We have shown that NLP-22 and mammalian NMS are structurally similar (Fig. 8). In addition, NLP-22 and NMS show intriguing functional similarities. NMS shows a diurnal pattern of mRNA expression and is predominately expressed in a small set of central nervous system neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus7. Like NMS, NLP-22 cycles its expression, only as the output of a larval-based clock, and like NMS, NLP-22 is selectively expressed, in a single neuron pair, the RIAs (Fig. 1c). While the suprachiasmatic nucleus is well known as the master circadian clock pacemaker50, a role for the RIAs in regulating the analogous larval clock in C. elegans has not been reported. The RIAs are required for C. elegans memory behaviors35, 48, behaviors that in mammals are sensitive to the sleep-wake history of the animal51.

Central nervous system administration of NMS into mammals and birds inhibits feeding behavior52–55. NLP-22 over-expression causes an almost complete block of feeding in C. elegans (Fig. 2). Central nervous system administration of NMS in rats causes an inhibition of locomotion and a phase shift of the circadian behavioral rhythm7. NLP-22 over-expression causes behavioral quiescence during the normally active adult stage (Fig. 2). Our work predicts effects of NMS on sleep behavior, but to our knowledge this has not yet been tested.

While there are functional and structural similarities between NLP-22 and NMS, there are also clear differences. Mammalian NMS has a highly conserved C-terminal RN motif that is not present in C. elegans NLP-22. When we over-expressed human NMS(17–33), which contains the 17 C-terminal amino acids of NMS including the amino acids conserved with NLP-22 and which is predicted to form a similar three-dimensional structure as NLP-22 and full length NMS (Supplementary Fig. S2a), we did not observe behavioral quiescence in C. elegans (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Furthermore, we could not identify genes coding for proteins predicted to be processed into NLP-22 or NMS-like peptides in the genomes of insects or fish. Finally, loss of function of each of four G-protein coupled receptors that are weakly similar to a mammalian NMS receptor56 did not suppress the NLP-22-induced quiescence (Supplementary Table S1). Neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors often show co-evolution, leading to difficulty in identifying homologs across phyla57. Thus, future additional data, including the identification of the NLP-22 post-synaptic signaling pathway, will be required to determine whether NLP-22 and NMS are true homologs.

In summary, our work defines the first role for a somnogenic neuropeptide in C. elegans and identifies a pair of neurons, the RIAs, in the regulation of C. elegans sleep-like behavior. While C. elegans sleep-like behavioral research is still in its nascent stage, the simplicity of this model animal’s nervous system combined with recent progress in the identification of cells involved in sleep-like behavioral regulation13–15, 58, 59 holds promise for rapid future progress in delineating the genes and circuits regulating sleep and wake.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation methods and Strains

Animals were cultivated on NGM agar and, unless noted otherwise, were fed the OP50 E. coli derivative strain DA83760. All experiments were performed on hermaphrodites. The following strains were used in this study: N2 (Bristol), EG4322 ttTi5605 II; unc-119(ed3)III, TJ375 gpIs1[Phsp-16.2::gfp], NQ156 lin-15(n765ts)X; qnEx48[Pins-4:gfp:PEST; lin-15(+)], NQ216 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx95[Phsp-16.2::nlp-22; Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], IB16 ceh-17(np1)I, NQ230 ceh-17(np1)I; qnEx95, NQ235 nmur-4(ok1381)I; qnEx95, NQ250 qnIs101[Pnlp-22:nlp-22:gfp; Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ251 qnIs142[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22; Phsp-16.2:gfp; Pmyo-2:mCherry, unc-119(+)], DA509 unc-31(e928)IV, NQ256 unc-31(e928)IV;qnEx95, NQ266 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx128[Pnlp-22:gfp:nlp-22; Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ269 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx131[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(No Signal Sequence); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ270 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx132[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(No Signal Sequence); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ274 nmur-1(ok1387)X; qnEx95, NQ275 nmur-3(ok2295)X; qnEx95, NQ282 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx139[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(No Signal Sequence); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ285 nmur-2(ok3502)II; qnEx95, NQ305 sid-1(pk3321)V; qnIs137[Pdpy-7:nlp-22(RNAi); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ314 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx160[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(KR→AA); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], KP1873 egl-3(nu349)V, NQ319 egl-3(nu349)V; qnEx95, KP2018 egl-21(n476)IV, NQ320 egl-21(n476)IV;qnEx95, MT1074 egl-4(n479)IV, NQ321 egl-4(n479)V;qnEx95, NQ333 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx162[Pnlp-22:Intron:gfp; Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ367 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx178[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(KR→AA); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ374 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx185[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→MRPG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ375 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx186[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→MRPG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ376 sid-1(pk3321)V; qnIs157[glr-3:nlp-22(RNAi); myo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ378 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx187[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→FEPG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ379 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx187[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→FEPG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ383 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx192[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→FRPE); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ392 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx188[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→FREG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ393 unc-119(ed3)III;qnEx189[Phsp-16.2:nlp-22(FRPG→FREG); Pmyo-2:mCherry; unc-119(+)], NQ448 unc-119(ed3)III; qnEx224[Pglr-3:ChR2::YFP (Regular) + unc-122:gfp + unc-119(+)] ARF240 aaaIs1[Phsp-16::lin-42a::unc-54utr; Pmyo-2:dsRed], NQ596 nlp-22(gk509904)X, NQ603 nlp-22(gk509904)X; qnEx311[nlp-22(+); Pmyo-2:Cherry], KG532 kin-2(cd179)X, NQ606 kin-2(cd179)X; qnIs142; VC40199 nlp-22(gk509904)X; NQ667 kin-2(ce179)X; qnEx95, NQ668 egl-4(n479)IV; qnIs142, NQ670 qnEx95, VM1345 lin-15(n765ts)X; akEx211[Pglr-3:gfp; Pglr-3:ICE; lin-15(+)], RB1288 nmur-1(ok1387)X, RB2526 nmur-2(ok3502)II, VC1974 nmur-3(ok2295)X, RB1284 nmur-4(ok1381)I

Molecular biology and transgenesis

All DNA constructs were made using overlap-extension PCR61. Briefly, to fuse two or more DNA fragments, we amplified (Herculase Enhanced DNA Polymerase, Agilent Technologies) the individual DNA fragments with oligonucleotides that included 5′-extensions complementary to the fusion target. Individually-amplified DNA fragments were then mixed without primers in the presence of DNA polymerase in order to anneal and extend the fused product. The fused product was purified (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, Qiagen) and amplified using nested primers. The size of the final PCR product was verified by gel electrophoresis61. Oligonucleotides used for making these constructs are listed in Supplementary Table S3. For nlp-22 over-expression, the promoter of hsp-16.2 was amplified from the vector pPD49.83 (obtained from Addgene) and fused to the genomic sequence of nlp-22(+1 to +1451) (where nucleotide number refers to the nucleotide position relative to the start site of translation). Both the extrachromosomal array, qnEx95, and the integrated array, qnIs142, were analyzed in each behavioral assay. The mutated nlp-22 over-expression constructs (No signal sequence (SS), KR→AA, FRPG→MRPG, FRPG→FEPG, FRPG→FREG, FRPG→FRPE) were created by introducing the desired mutations by overlap-extension PCR using oligonucleotide 5′-extensions that encoded the amino acid changes61. Each mutated fused PCR product was cloned into a pCR™2.1-TOPO® TA Vector (Invitrogen™) and then sequenced to verify that the intended mutation but no other mutation was introduced. At least two and often three independent lines were analyzed for each behavioral analysis. To make a fusion protein in which GFP is at the c-terminus of the NLP-22 protein, the genomic sequence of nlp-22 (−450 to +701) was fused in frame to gfp followed by the unc-54 3′UTR, which was amplified from the vector pPD95.75 (Addgene). To make a fusion in which GFP is at the N-terminus of the NLP-22 protein, the promoter (−450 to +3) of nlp-22 was fused to the coding sequence of GFP amplified from pPD95.75 only excluding the stop codon, and fused in frame to the genomic sequence of nlp-22 (+1 to +701), which included the nlp-22 3′UTR. The transcriptional reporter for nlp-22 (Pnlp-22:Intron:gfp) was made by fusing the promoter of nlp-22 (−450 to +3) to the coding sequence of GFP, amplified from pPD95.75, and replacing one of the synthetic introns of gfp with the intron of nlp-22(+85 to +481). To drive expression of nlp-22 dsRNA in the RIA neurons, the promoter of glr-3(−5500 to −1) was fused to the genomic sequence of nlp-22 spanning the region +13 to +653 in the sense orientation, and, in a separate reaction, to the nlp-22 genomic sequences spanning the same nucleotides in the anti-sense orientation. These constructs lack a start codon and 3′UTR of nlp-22. To drive expression of nlp-22 dsRNA in the hypodermis, the promoter of dpy-7 (−417 to −1) amplified from N2 genomic DNA was fused to nlp-22 sense and anti-sense DNA. The genomic rescuing fragment of nlp-22 spanned from −450 to +1451 relative to the nlp-22 start codon. To over-express Neuromedin S (17-33) (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc), we replaced the coding sequence for the nlp-22 peptide with the coding sequence for Neuromedin S (17-33) and fused the nlp-22-NMS(17-33) chimeric sequence to the heat shock promoter.

Transgenic animals were created by microinjection62 using a Leica DMIRB inverted DIC microscope equipped with an Eppendorf Femtojet microinjection system. EG4322 animals were injected with 25–50ng/μl of each construct in combination with 5ng/μl pCFJ90 [Pmyo-2:mCherry], with 50–100 ng/μl of Punc-122:gfp, or 5ng/μl of pCFJ104, Prab-3::mCherry) and pCFJ151 [unc-119(+)] up to a total concentration of 150 ng/μl. To make the nlp-22 RNAi strains, 25 ng/μl of nlp-22(sense) and nlp-22(anti-sense) were injected together with the transgenesis markers pCFJ90 and pCFJ151. For behavioral experiment using transgenic animals carrying extrachromosomal arrays at least two distinct lines were analyzed. In most cases, quantitative behavioral analysis was performed only on one of these transgenic lines but in all cases the other line(s) gave the same qualitative result.

The integrated transgenes qnIs101, 137, 142, and 157 were constructed by UV irradiation of the extrachromosomal transgenes qnEx101, 137, 142, and 15763. A mix of approximately 100 L4 and adult transgenic animals were placed in a Spectrolinker XL-1500 UV Crosslinker (Spectronics Corporation) and exposed to 30,000 μJ/cm2 of ultraviolet light. Irradiated animals were plated at a density of five animals per plate, and grown for multiple generations. Integrants were identified as those that produced 100% transgenic progeny. Each integrated strain was out-crossed to the wild-type strain a minimum of 3 times before analysis.

The strain VC40199 containing the nlp-22(gk509904) X allele was produced by the million mutation project64 and obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Consortium. The CGA to TGA mutation in nlp-22 reported for this strain was verified by sequencing a genomic PCR fragment, which was PCR-amplified using the primers oNQ552 and oNQ534 (Supplementary Table S3). The strain NQ596 nlp-22(gk509904) X was generated by crossing the strain VC40199 to N2 males, and then crossing resultant males back to VC40199. This procedure was repeated 4X. A twitcher phenotype, which was present in VC40199 animals, was not present in the out-crossed NQ596 animals.

Over-expression analysis

For all over-expression experiments, animals carrying arrays with inducible heat-shock promoters were grown to young adulthood at 20°C, transferred to the surface of NGM agar 6-cm diameter plates fully seeded with a lawn of DA837 E. coli bacteria, wrapped in Parafilm, and immersed in a 33°C water bath for 30 minutes. Heat-shocked animals were placed at 20°C prior to analysis. Pharyngeal pumping and body bends were counted during 20 second and 1 minute intervals, respectively. Arousal threshold was determined by measuring the latency to respond to exposure to blue light65, or exposure to a hair dipped in a freshly prepared mixture of 30% octanol and 70% ethanol66. Response to octanol was defined as backwards movement of the magnitude corresponding to one third of the worm’s length. Response to blue light was defined as movement (either forward or backwards) of magnitude equal to one half of the animal’s body length. Arousal threshold assays of nlp-22 mutants and nlp-22 mutants carrying a rescuing transgene were performed by an investigator who was blinded to genotype. The blinding was setup by a colleague without the use of a computer randomization program. It was impossible to blind the investigator to the genotype of the nlp-22(OE) transgenic animals because these animals were extremely quiescent and retained excessive eggs.

In experiments designed to assess the effects of mild over-expression of nlp-22 on direction of locomotion, animals were analyzed one hour after a 15 minute 33°C heat exposure. Behavior was assessed on an agar surface devoid of bacteria. During a 120-second period, we measured with a hand-held timer the total time spent moving forward as well as the total time spent moving backwards. The average of 20 experimental animals expressing Phsp16.2:nlp-22 (qnIs142) was compared with the average of 20 control N2 animals.

Imaging of fluorescence

For GFP and differential interference contrast imaging, animals were mounted on 5% agar pads, immobilized with 15 mM levamisole, and observed through a 63X or 100X objective lens on a Leica DM5500B microscope. Leica LAS software was used to capture images.

Quiescence measurements

For automated measurements of lethargus quiescence we placed single larvae in molded, concave polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) wells of diameter 3 mm and depth 2.5 mm, filled with 15 ul of NGM agar and seeded with DA837 bacteria. In each experiment, we placed one experimental and one control animal into two adjacent wells and the PDMS was then placed on a Diagnostics Instruments microscope base and illuminated for bright field microscopy, using white light supplied to the base with a fiber optic cable from a Schott DCR III light source. A camera (659x494 pixels, scA640-70fm, Basler Vision Technologies) mounted on a Zeiss Stemi 2000 stereomicroscope captured an image with 8-bit grayscale of both wells every 10 seconds. At this magnification and our camera acquisition setting, the spatial resolution was 12.5 micrometers per pixel. To quantify quiescence, we monitored animals for time a period between 12 and 48 hours, and used a machine vision frame subtraction principle to identify 10-second epochs of behavioral quiescence12, 27, 67. Recordings were performed in an environmental room at 19±2°C. In comparison to conditions used in prior quiescence measurements, the room temperature was lower and pixel resolution was reduced, leading to quiescence measurements that were greater than those previously reported12. For each experimental condition, quiescence of at least six animals was measured because we previously found this number to be sufficient to detect a difference in quiescence12. For most conditions, 9–11 animals were used. Data was discarded if the temperature of the room exceeded 21°C due to equipment malfunction or if one of the two worms burrowed in the agar. Quiescence data from VM1345 was discarded when, upon inspection with epifluorescence, we determined that neither RIA had died. We censored 12% of the VM1345 data for that reason.

qPCR

L2 or L3 worms were picked to fresh plates seeded with DA837 bacteria and allowed to enter lethargus. We identified worms in L2 or L3 lethargus, using a Leica MZ16 stereomicroscope, by an absence of locomotion and feeding. A subset of worms was harvested for RNA isolation in either L2 or L3 lethargus while the remaining animals were allowed to mature for additional durations prior to harvesting. The experiment was performed at 25°C to speed development. L4 lethargus animals were similarly identified by first transferring mid L4 animals to a fresh agar dish seeded with DA837, and then harvesting animals that had stopped moving and feeding.

To test lin-42-dependent induction of nlp-22 mRNA, ARF240 first day adult animals, which were cultivated at 15°C, were submersed while housed on an NGM agar surface fully seeded with bacteria in a 33°C water bath for 30 minutes and then recovered at 25°C. Control N2 animals were treated identically. RNA was collected before heat-shock treatment and at 4, 6, and 8 hours after the end of the heat treatment.

Total RNA was harvested from each population using an RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript® one-step RT-PCR system (Invitrogen). We performed three or more biological replicates in each experiment and for each biological replicate we used the average of two technical real-time PCR replicates. Real-time PCR was performed using Taqman® Gene Expression Mastermix on an Applied Biosystems 7500 platform at the core services within the Penn Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI 045008). Oligonucleotides used for the real-time PCR analysis were purchased from IDT and their sequences are shown in Table S3. Relative mRNA was determined by the delta-delta method68 by normalization to the expression of the gene pmp-369.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amita Sehgal, Liliane Schoofs, and Lotte Frooninckx for comments. This work was supported by NIH grants T32HL07713 to M.D.N. (PI, Allan Pack), T31HL07953 to N.F.T. (PI, Allan Pack), R01NS064030 to D.M.R., a NARSAD Young Investigator Award to D.M.R, a McCabe Foundation grant to D.M.R., a Penn University Scholars Award to C-C.Y., and by an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Research Fellowship to C.F-Y. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). The strain ARF240 was provided by A. Frand and the strain VM1345 was provided by A. Maricq.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.D.N., N.F.T., C.F-Y., and D.M.R. designed and performed experiments and wrote paper, J.B.G-R designed experiments, C.C.Y and C.J.S. performed experiments.

Competing financial Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lin L, et al. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng MY, et al. Prokineticin 2 transmits the behavioural circadian rhythm of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nature. 2002;417:405–10. doi: 10.1038/417405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer A, et al. Regulation of daily locomotor activity and sleep by hypothalamic EGF receptor signaling. Science. 2001;294:2511–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1067716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu YL, et al. Neuropeptide S: a neuropeptide promoting arousal and anxiolytic-like effects. Neuron. 2004;43:487–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin SH, et al. Prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) promotes awakening and suppresses absence seizures. Neuroscience. 2002;114:229–38. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huitron-Resendiz S, et al. Urotensin II modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of brainstem cholinergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5465–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4501-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori K, et al. Identification of neuromedin S and its possible role in the mammalian circadian oscillator system. EMBO J. 2005;24:325–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parisky KM, et al. PDF cells are a GABA-responsive wake-promoting component of the Drosophila sleep circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:672–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crocker A, Sehgal A. Genetic analysis of sleep. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1220–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1913110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renn SC, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, Taghert PH. A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;99:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh RN, Sulston JE. Some Observations on Molting in Caenorhabditis-Elegans. Nematologica. 1978;24:63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raizen DM, et al. Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature. 2008;451:569–72. doi: 10.1038/nature06535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driver RJ, Lamb AL, Wyner AJ, Raizen DM. DAF-16/FOXO regulates homeostasis of essential sleep-like behavior during larval transitions in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2013;23:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Buskirk C, Sternberg PW. Epidermal growth factor signaling induces behavioral quiescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1300–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi S, Chatzigeorgiou M, Taylor KP, Schafer WR, Kaplan JM. Analysis of NPR-1 reveals a circuit mechanism for behavioral quiescence in C. elegans. Neuron. 2013;78:869–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon M, Gardner HF, Miller EA, Deshler J, Rougvie AE. Similarity of the C. elegans developmental timing protein LIN-42 to circadian rhythm proteins. Science. 1999;286:1141–6. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monsalve GC, Van Buskirk C, Frand AR. LIN-42/PERIOD controls cyclical and developmental progression of C. elegans molts. Curr Biol. 2011;21:2033–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konopka RJ, Benzer S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:2112–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathoo AN, Moeller RA, Westlund BA, Hart AC. Identification of neuropeptide-like protein gene families in Caenorhabditiselegans and other species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14000–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241231298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gissendanner CR, Crossgrove K, Kraus KA, Maina CV, Sluder AE. Expression and function of conserved nuclear receptor genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2004;266:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Z, Pym EC, Babu K, Vashlishan Murray AB, Kaplan JM. A neuropeptide-mediated stretch response links muscle contraction to changes in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2011;71:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart AC. In: Wormbook, ed. Ambros V, editor. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raizen D, Song BM, Trojanowski N, You YJ. Methods for measuring pharyngeal behaviors. WormBook. 2012:1–13. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.154.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Kim K. Neuropeptides. WormBook. 2008:1–36. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.142.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwanir S, et al. The microarchitecture of C. elegans behavior during lethargus: homeostatic bout dynamics, a typical body posture, and regulation by a central neuron. Sleep. 2013;36:385–95. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belfer SJ, et al. Caenorhabditis-in-drop array for monitoring C. elegans quiescent behavior. Sleep. 2013;36:689–698G. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husson SJ, Clynen E, Baggerman G, Janssen T, Schoofs L. Defective processing of neuropeptide precursors in Caenorhabditis elegans lacking proprotein convertase 2 (KPC-2/EGL-3): mutant analysis by mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1999–2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husson SJ, et al. Impaired processing of FLP and NLP peptides in carboxypeptidase E (EGL-21)-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans as analyzed by mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 2007;102:246–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speese S, et al. UNC-31 (CAPS) is required for dense-core vesicle but not synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6150–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1466-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schade MA, Reynolds NK, Dollins CM, Miller KG. Mutations that rescue the paralysis of Caenorhabditis elegans ric-8 (synembryn) mutants activate the G alpha(s) pathway and define a third major branch of the synaptic signaling network. Genetics. 2005;169:631–649. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman JE, Naidoo N, Raizen DM, Pack AI. Conservation of sleep: insights from non-mammalian model systems. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlie NK, Schade MA, Thomure AM, Miller KG. Presynaptic UNC-31 (CAPS) is required to activate the G alpha(s) pathway of the Caenorhabditis elegans synaptic signaling network. Genetics. 2006;172:943–61. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.049577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan J, Shaham S, Ledoux S, Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75:641–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stetak A, Horndli F, Maricq AV, van den Heuvel S, Hajnal A. Neuron-specific regulation of associative learning and memory by MAGI-1 in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miura M, Zhu H, Rotello R, Hartwieg EA, Yuan J. Induction of apoptosis in fibroblasts by IL-1 beta-converting enzyme, a mammalian homolog of the C. elegans cell death gene ced-3. Cell. 1993;75:653–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90486-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagel G, et al. Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husson SJ, Clynen E, Baggerman G, De Loof A, Schoofs L. Discovering neuropeptides in Caenorhabditis elegans by two dimensional liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez R, et al. Phylemon 2.0: a suite of web-tools for molecular evolution, phylogenetics, phylogenomics and hypotheses testing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W470–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maupetit J, Derreumaux P, Tuffery P. PEP-FOLD: an online resource for de novo peptide structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W498–503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jewett KA, Krueger JM. Humoral sleep regulation; interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. Vitam Horm. 2012;89:241–57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394623-2.00013-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Candido EP. The small heat shock proteins of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: structure, regulation and biology. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2002;28:61–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56348-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abrahante JE, Miller EA, Rougvie AE. Identification of heterochronic mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Temporal misexpression of a collagen::green fluorescent protein fusion gene. Genetics. 1998;149:1335–51. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mori I, Ohshima Y. Neural regulation of thermotaxis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1995;376:344–8. doi: 10.1038/376344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Z, et al. Two insulin-like peptides antagonistically regulate aversive olfactory learning in C. elegans. Neuron. 2013;77:572–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris G, et al. Dissecting the serotonergic food signal stimulating sensory-mediated aversive behavior in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhara A, Mori I. Molecular physiology of the neural circuit for calcineurin-dependent associative learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9355–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0517-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendricks M, Ha H, Maffey N, Zhang Y. Compartmentalized calcium dynamics in a C. elegans interneuron encode head movement. Nature. 2012;487:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibuka N, Kawamura H. Loss of circadian rhythm in sleep-wakefulness cycle in the rat by suprachiasmatic nucleus lesions. Brain Res. 1975;96:76–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maquet P. The role of sleep in learning and memory. Science. 2001;294:1048–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1062856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ida T, et al. Neuromedin S is a novel anorexigenic hormone. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4217–4223. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shousha S, et al. Effect of neuromedin S on feeding regulation in the Japanese quail. Neurosci Lett. 2006;391:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tachibana T, Matsuda K, Khan MS, Ueda H, Cline MA. Feeding and drinking response following central administration of neuromedin S in chicks. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2010;157:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Atsuchi K, et al. Centrally administered neuromedin S inhibits feeding behavior and gastroduodenal motility in mice. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:535–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maier W, Adilov B, Regenass M, Alcedo J. A neuromedin U receptor acts with the sensory system to modulate food type-dependent effects on C. elegans lifespan. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moyle WR, et al. Co-evolution of ligand-receptor pairs. Nature. 1994;368:251–5. doi: 10.1038/368251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarz J, Lewandrowski I, Bringmann H. Reduced activity of a sensory neuron during a sleep-like state in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2011;21:R983–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallagher T, Kim J, Oldenbroek M, Kerr R, You YJ. ASI regulates satiety quiescence in C. elegans. J Neurosci. 2013;33:9716–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4493-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis MW, et al. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans Na,K-ATPase alpha-subunit gene, eat-6, disrupt excitable cell function. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8408–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson MD, Fitch DH. Overlap extension PCR: an efficient method for transgene construction. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;772:459–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-228-1_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stinchcomb DT, Shaw JE, Carr SH, Hirsh D. Extrachromosomal DNA transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3484–96. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson O, et al. The Million Mutation Project: A new approach to genetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2013 doi: 10.1101/gr.157651.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belfer S, et al. Caenorhabditis-in-drop array for monitoring C. elegans quiescent behavior. Sleep. 2013 doi: 10.5665/sleep.2628. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chao MY, Komatsu H, Fukuto HS, Dionne HM, Hart AC. Feeding status and serotonin rapidly and reversibly modulate a Caenorhabditis elegans chemosensory circuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15512–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403369101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmerman JE, Raizen DM, Maycock MH, Maislin G, Pack AI. A video method to study Drosophila sleep. Sleep. 2008;31:1587–98. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoogewijs D, Houthoofd K, Matthijssens F, Vandesompele J, Vanfleteren JR. Selection and validation of a set of reliable reference genes for quantitative sod gene expression analysis in C. elegans. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.