Abstract

Purpose

This study examined three research questions: 1) Is there an association between maternal early-life economic disadvantage and the birth weight of later-born offspring? (2) Is there an association between maternal abuse in childhood and the birth weight of later-born offspring? And, (3) to what extent are these early-life risks mediated through adolescent and adult substance use, mental and physical health status, and adult socioeconomic status?

Methods

Analyses used structural equation modeling to examine data from two longitudinal studies that include three generations. The first (G1) and second generation (G2) were enrolled in the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and the third generation (G3) was enrolled in the SSDP Intergenerational Project. Data for the study (N = 136) focused on SSDP (G2) mothers and their children (G3).

Results

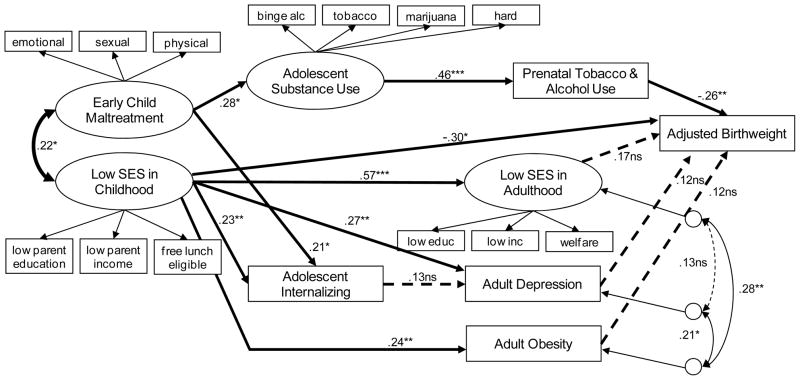

Analyses revealed G2 low childhood socioeconomic status predicted G3 offspring birth weight. Early childhood abuse among G2 respondents predicted G3 offspring birth weight through a mediated pathway including G2 adolescent substance use and G2 prenatal substance use. Birth weight was unrelated to maternal adult SES, depression or obesity.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the impact of maternal early-life risks of low childhood socioeconomic status and child maltreatment on later-born offspring birth weight. These findings have far-reaching effects on the cumulative risk associated with early-life-economic disadvantage and childhood maltreatment. Such findings encourage policies and interventions that enhance child health at birth by taking the mother’s own early-life and development into account.

INTRODUCTION

Low birth weight (LBW, < 2500 g) is a leading cause of infant mortality and morbidity in the U.S. In the first year of life, LBW infants die at rates of up to 40 times those infants of normal weight [1] and surviving infants are at elevated risk for long-term health and cognitive impairments [2]. Risk factors for LBW are multifactorial, thus extensive efforts have been made to identify the risk factors, as well as medical obstetric history, and biophysical factors associated with or that predict LBW [1]. Despite this substantial research as well as advances in obstetric care, the rate of LBW has increased over the past two decades [3]. Some posit that the increase in LBW is due to the rise in multiple births, changes to labor and delivery procedures, advanced maternal age, and maternal health conditions (e.g., obesity). However, knowledge of the presence of these maternal risk factors has not reduced the incidence of LBW [1].

A possible explanation for the lack of progress in reducing the prevalence of LBW may be the prevailing notion that pregnancy is a relatively acute condition [4]. Some posit that the prenatal period is too limited a time to effectively address the needs of women at greatest risk for delivering LBW infants [5] because many risk factors are difficult to successfully address during pregnancy [6]. In comparison, a life-course perspective suggests that maternal early-life experiences may be important determinants of maternal health in adulthood and the health of her children [7]. Some studies have attempted to examine the association between early-life factors and offspring birth weight. Colen [8] examined the extent to which upward socioeconomic mobility reduced the probability of delivering LBW infants among Black and White women who were poor during childhood. Their findings suggest that upward socioeconomic mobility contributed to a lower probability of LBW among White women but not among upwardly mobile Black women. In a British cohort study, Hypponen [9] reported an association between offspring birth weight and maternal height at age 7.

Despite the influence of some maternal childhood conditions on offspring birthweight, our understanding of the pathways that link early-life conditions with offspring birth weight remains largely unexplored. This is due in part to the fact that most studies of the predictors of LBW tend to be cross-sectional in design and perinatally focused [4].

The study focuses on a life-course perspective which acknowledges the importance of early-life factors as important precursors of offspring birth weight. We investigated two pathways that link maternal early-life adversity to offspring birth weight through known risk factors for LBW at subsequent periods of the life-course. The first pathway examines the impact of maternal low childhood socioeconomic status (SES) and birth weight in her later-born offspring. Numerous studies suggest that social status and health-related factors in early-life have an effect on both social status and health in later-life [10]. Such that, individuals exposed to economic disadvantage in childhood are more likely be exposed to adverse health factors across the life-course, resulting in a comprised health status in later-life [10]. Further, research has shown low SES in childhood predicts offspring birth weight [8]. However to our knowledge, this has not been examined in a prospective, longitudinal study using direct assessments of economic status. Further, no study has examined potential mechanisms that link low childhood SES to offspring LBW. The second proposed pathway examines the impact of maternal childhood abuse on offspring birth weight. A large volume of work demonstrates the behavioral, social, cognitive, and emotional pathways linking child maltreatment with adverse health outcomes in adolescence and adulthood [11]. However, less is known about how child maltreatment may affect pregnancy outcomes. To our knowledge, there are no studies that examine the mediated or unmediated pathways linking childhood maltreatment with low birth weight in later-born offspring. This is a noted limitation because individuals who report childhood maltreatment are more likely to engage in adverse health behaviors in adolescence and adulthood which may increase the risk of delivering low birth weight infants. Previous studies have found child abuse predicts cigarette smoking [12] and substance use [13–15]. Childhood abuse is also associated with increased risk of internalizing problems such as adolescent and adult depression [16]. Considering prenatal substance use and maternal depression independently increases the risk of poor fetal growth [17], we examined the link between maternal childhood abuse and offspring birthweight.

Using data from a longitudinal cohort study, extending over three generations, we examined the following questions: (1) Is there an association between maternal early-life economic disadvantage and the birth weight of later-born offspring? (2) Is there an association between maternal abuse in childhood and the birth weight of later-born offspring? And, (3) to what extent are these early-life risks mediated through adolescent and adult substance use, mental and physical health status, and adult SES?

METHODS

Sample and Procedure

We use data from two longitudinal studies with first (G1), second (G2) and third (G3) generation participants. The sample draws from participants in the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) who were followed from ages 10 to 27 years. The sample of 808 students (G2) and their parents (G1), recruited from 18 elementary schools in Seattle, Washington in 1985, includes equal numbers of males and females (50%) and is ethnically diverse: 47% Caucasian, 26% African American, 22% Asian American, and 5% Native American. Fifty-two percent experienced poverty in childhood, as measured by eligibility for the federal school lunch program at ages 10 – 13 years.

As G2 participants began having their own families, eligible SSDP parents (G2) who agreed to participate (N=288) and their eldest biological child (G3) were enrolled in the Intergenerational Project (TIP). To identify possible selection biases in recruitment from SSDP to TIP, we examined whether there were differences in eligibility, and, once eligible, if there were differences in recruitment, and once recruited, whether there were differences in retention by a number of sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics. The only significant eligibility difference was for gender: G2 mothers were more likely to have regular contact with the G3 child than were G2 fathers (97% vs. 84%, respectively). There were no differences in recruitment or retention. Of the 288 SSDP parents participating in TIP, 180 were mothers. Data for the present analyses (N=136) focused on SSDP mothers who had their first child after age 18. All TIP interviews were conducted in-person via computer-assisted software. Analyses used full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML). Across study variables, 2.6% of data points were missing. The effective sample size [18] for these analyses was calculated at n = 132 (approximately 97.6% of the total sample of 136). The Human Subjects Review Committee at the University of Washington approved all SSDP and TIP study procedures and measures.

Measures

G3 Adjusted Birth Weight

Maternal self-reported data was used to obtain offspring birth weight. Birth weight was adjusted for gestational age and child gender by use of national reference data [19]. Analyses were conducted on the gestational age and gender adjusted percentile scores of the children's weight at birth.

G2 Early Childhood Maltreatment

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire short form (CTQ-SF) was administered at age 24 to retrospectively assess for childhood (before age 10) experiences of maltreatment [20]. The CTQ-SF is a 28-item self-report, retrospective inventory of child maltreatment histories that assesses for physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. The CTQ-SF scales demonstrate good internal consistency across samples [20]. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never true” to “very often true”, G2 respondents indicated the frequency with which each question applies to his or her experience of child maltreatment before age 18 years. If a respondent responded affirmatively to an item before age 18, the item was followed up with a question asking whether the item had been experienced before age 10. Responses were summed to derive a total number of items to which each participant responded affirmatively before age 10 in each domain of maltreatment.

G2 Low Childhood SES

Risks included low G1 parental education (a count measure of years of education), low G1 parental income (annual income adjusted for household size), and G2 eligibility for the National School Lunch/School breakfast program at age 11, 12, or 13 (coded as yes = 1, no = 0).

G2 Adolescent Substance Use

Mothers (G2) reported prospectively on their own binge drinking (5 or more drinks per occasion), cigarette, marijuana and other drug use when they were in 9th, 10th, and 12th grade. At each wave, respondents were asked how many times they had engaged in each of these behaviors during the month prior to the interview. Average frequency of binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use and other illicit drug use scores were obtained by averaging use from 9th–12th grade. Since the distributions of these variables were highly skewed, frequency scores for each substance were grouped into three categories that still captured meaningful levels of use: binge drinking and marijuana use – 0 (never), 1 (once or less per week), 2 (more than once per week); cigarette use - 0 (never), 1 (less than 1 pack per day), 2 (1 pack or more per day), other drug use (i.e., crack, cocaine, amphetamines, tranquilizers, sedatives, psychedelics, and narcotics) 0 (never), 1 (once or less per week), 2 (more than once per week).

G2 Internalizing Behavior

Teachers assessed G2’s early adolescent behavior and psychological problems using the complete Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [21] at age 11 to 14. Scales were constructed following Lengua [22], which have shown better sensitivity, predictive power, and discriminate validity than the original CBCL subscales [22]. For the study, the depression scale (9 items: feels worthless, unhappy, lonely; mean α = .72) from the CBCL was used to assess adolescent internalizing. The depression scale was determined to have good reliability and validity with both clinical and nonclinical samples [22].

G2 Prenatal Tobacco and Alcohol Use

Mothers (G2) reported prospectively on the frequency of prenatal tobacco and alcohol exposure. Tobacco use response categories were coded 0 = never; 1 = less than one cigarette a day; 2 = daily smoking of one or more cigarettes. Alcohol use response categories were coded 0 = never; 1 = almost never; 2 = less than once a month or more. Prenatal tobacco and alcohol exposure measures were then standardized and averaged into an index.

G2 Low Adult SES

Low G2 SES in adulthood was indicated by low educational attainment (1=less than 8th grade to 11=post four-year college/professional degree), low parental income (annual income adjusted for household size) and G2 receipt of AFDC, TANF, or Food Stamps in the first year of TIP (coded as yes = 1, no = 0).

G2 Adult BMI

We controlled for the potential contribution of maternal body mass index to infant birth weight because of the elevated risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes among obese women [23]. BMI was determined from self-reports of height and weight when participants were ages 24, 27, and 30 years. BMI scores were then averaged. Respondents were classified: 1 = underweight, 2 = normal weight, 3 = overweight and 4 = obese [24].

G2 Adult Depression

Past-year depressive episode was assessed based on DSM-III-R criteria using a modified version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) [25]. The DIS was administered when participants at ages 24, 27, and 30. We averaged the number of times respondents met depression diagnostic criteria to create an index. The DIS has been used in studies of psychiatric disorders among adults in the general population and has demonstrated to be valid and reliable [26].

Analytic Strategy

The hypothesized inter-generational relations between G2 early and later-life risk factors for G3 birth weight was evaluated using MLE in Amos 18.0 [27]. Modeling was done in two stages. First, we evaluated the measurement model by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of G2 early child maltreatment, G2 low childhood SES, G2 adolescent substance use, and G2 low adulthood SES. Next, we analyzed the hypothesized structural relations between G2 and G3 latent factors. We report three indicators of model fit assessment: the chi-square estimate (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of all study variables. The CFA of latent constructs suggests support for the hypothesized measurement model. Model fit was acceptable (χ2 [130] = 104, p < .04, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .043). In preliminary analyses of these data, race (coded as Black v. non-Hispanic White) was included was significantly correlated with low SES in childhood (r = 0.29, p < .05). However, there was no association between the race variable and low birth weight, and the inclusion of race did not alter the other paths of the model, thus it was not included in subsequent models for parsimony. All indicators loaded significantly on their respective latent factors. Standardized loadings for emotional, sexual, and physical indicators on the G2 child maltreatment latent variable were .72, .54, and .73, respectively. Standardized loadings for low parent education, low income and participation in free/reduced lunch program on the G2 low childhood SES latent variable were .46, .87, and .77, respectively. Standardized loadings for adolescent binge drinking, tobacco use, marijuana use, and other drug use on the G2 adolescent substance use latent variable were .37, .76, .63, and .65, respectively. Finally, standardized loadings for low G2 education, low income, and welfare receipt on the low G2 adult SES latent variable were .56, .62, and .87, respectively. Table 2 presents the results of the bivariate correlation analyses of study variables. In general, cross-generation associations were significant. G2 early childhood maltreatment was positively and statistically associated with G2 adolescent substance use, G2 adolescent internalizing, G2 low adulthood SES, G2 adult depression, and G2 prenatal tobacco and alcohol use. G2 low childhood SES was positively and statistically associated with G2 adolescent internalizing, G2 low adulthood SES, G2 adult obesity, and G2 adult depression. At the level of zero-order correlations, only G2 prenatal tobacco and alcohol use was positively and statistically associated with G3 birth weight.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables in the Sample

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| G2 emotional abuse before age 10 | 33.0% |

| G2 sexual abuse before age 10 | 18.3% |

| G2 physical abuse before age 10 | 15.0% |

| G2 childhood parents’ education (years) | 12.5 (2.6) |

| G2 per capita childhood household income (1985–86) | $5,094 ($3,553) |

| G2 eligibility for free/reduced lunch (grades 5–7) | 58.1% |

| G2 adolescent alcohol binge drinking (grades 7–12) | 37.5% |

| G2 adolescent tobacco use (grades 7–12) | 27.9% |

| G2 adolescent marijuana use (grades 7–12) | 25.7% |

| G2 adolescent illicit drug use (grades 7–12) | 22.1% |

| G2 adolescent internalizing | 0.55 (0.22) |

| G2 adult DSM-IV depression criteria (ages 21–30) | 1.9 (2.1) |

| G2 adult BMI ( ages 21–30) | 2.9 (.8) |

| G2 educational attainment by age 30 (years)1 | 6.4 (2.4) |

| G2 per capita adult household income (ages 21–30) | $12,000 ($8,600) |

| G2 number of years welfare receipt (ages 21–30) | 1.0 (1.3) |

| G2 prenatal maternal tobacco use | 21.3% |

| G2 prenatal maternal alcohol use | 17.6% |

| G3 adjusted birth weight (percentile)2 | 42% (28%) |

Note: G2 denotes the respondents enrolled the SSDP. G3 denotes the index children born to the G2s. SD: standard deviation.

Educational attainment range 8 years – 18 or more years (coded 1–11).

Percentile mean for the adjusted birth weight was at the 42nd percentile, range: 14% percentile – 70% percentile.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Associations among Study Variables

| Latent variables & mediators | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G2 early childhood abuse | --- | ||||||||

| 2. G2 low SES childhood | 0.173 | --- | |||||||

| 3. G2 adolescent substance use | 0.262* | 0.191 | --- | ||||||

| 4. G2 adolescent internalizing | 0.259* | 0.289* | 0.351* | --- | |||||

| 5. G2 low SES adulthood | 0.234* | 0.577* | 0.368* | 0.310* | --- | ||||

| 6. G2 adult obesity | 0.067 | 0.224* | 0.014 | 0.036 | 0.337* | --- | |||

| 7. G2 adult depression | 0.260* | 0.306* | 0.169 | 0.212* | 0.279* | 0.249* | --- | ||

| 8. G2 prenatal tobacco & alcohol use | 0.192* | 0.024 | 0.446* | 0.206* | 0.207* | 0.132 | 0.087 | --- | |

| 9. G3 adjusted birth weight | 0.012 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.032 | 0.027 | 0.109 | 0.085 | 0.210* | --- |

p < .05

Structural Equation Model

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with MLE in Amos 18.0 [27] was used to examine the effects of low childhood SES and childhood maltreatment on birth weight. Adolescent substance use and internalizing problems, and adult prenatal substance use, low adult SES, adult obesity and adult depression were also tested as potential mediators of these early-life risks. Figure 1 presents the SEM and the standardized model parameter estimates. The measurement model of the latent variables in the SEM was identical in factor loadings to that described in the CFA. The SEM achieved adequate fit (CFI = .93, RMSEA = 0.045). Early childhood abuse significantly predicted more adolescent internalizing problems (β = 0.21, p < 0.03) and greater adolescent substance use (β = 0.28, p < 0.02). Low childhood SES significantly predicted more adolescent internalizing problems, and in adulthood, low SES, higher obesity, and more average depression. G2 adolescent substance use significantly predicted more prenatal substance use. G3 birth weight was significantly reduced by prenatal substance use (β = −0.26, p < 0.001), and, interestingly, once prenatal substance use was controlled, G2 low childhood SES significantly predicted G3 birth weight (β = −0.30, p < 0.03). The total variance accounted for in birth weight was 15%. Other model variables, included as potential mediators (adolescent internalizing, low adult SES, adult obesity, adult depression) did not significantly predict G3 birth weight either in the zero-order correlations or in the SEM.

Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

In the study, results suggest a mediated pathway of influence from early childhood abuse through adolescent substance use and prenatal substance use influencing G3 birth weight. In addition, results suggest that G2 low childhood SES predicts G3 birth weight in a manner unmediated by measures tested in this model.

The finding that low SES in childhood has an unmediated effect on offspring birth weight is consistent with earlier studies that have linked offspring birth weight to adverse socioeconomic conditions during their mothers’ childhood [8, 28]. Our findings differ from the results of a previous study in which both maternal SES in childhood and adulthood were independently associated with offspring birth weight [28]. A possible explanation for the divergent results was the fact that measures of adult SES differed. Astone [28] measured adult SES (measured as education and employment status) at the time of pregnancy while our study assessed adult SES at the time the G3 index child entered the study. In addition, while the earlier study did not have data on income at the time of pregnancy, our latent measure of adult SES included adult income. However, the utility of including adult SES in life-course studies remains unclear. Most life-course studies attempt to control the independent effect of later-life SES on later-life health outcomes. Yet, this adjustment may lead to underestimation of the influence of early-life SES on subsequent health outcomes by masking the indirect causal pathways from early-life risk factors to later-life health outcomes [7].

Support for our finding that low childhood SES may adversely affect offspring birth weight is based on biological evidence involving neuroendocrine processes. During the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of a normally developing pregnancy, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), a major hypothalamic regulator of human responses to stress [29], is present in maternal blood [30] and levels of CRH may play a role in determining the timing of parturition [31]. Elevated maternal plasma levels of CRH during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters have been linked to spontaneous preterm birth and fetal growth restriction [32]. Although the causal role of CRH in infant birth weight is unclear, increased maternal plasma CRH may be an indicator of potential maternal/fetal distress or increased metabolic and physiological demands [30]. Future studies are needed to examine whether social position, measured as childhood SES, may also be linked to elevated maternal plasma levels.

In addition, we did find support for evidence of a mediated pathway from early child maltreatment through adolescent and prenatal substance use to offspring birth weight. To our knowledge, this is the first study to establish a link between childhood abuse and offspring birth weight in a community sample of women not at high risk to deliver LBW infants [33]. In the present study, a mechanism of influence of childhood maltreatment on substance use appears to be through initiation of substance use in adolescence [15]. Earlier studies have found childhood abuse predicts substance use, especially among women [13–15]. Our findings are consistent with an earlier study which found that physical abuse in early childhood predicted substance use in early adolescence for females [15]. Some posit that individuals who experienced abuse in childhood did not develop the constructive coping strategies to deal with acute and chronic stressors and so they use alcohol and drugs to cope or self-medicate [34]. It has also been suggested that women, compared to men, are more likely to use substances if they were abused as children. In general, men are at higher risk than women for substance use because social sanctions against alcohol and drug use are stronger for women than for men [13]. The added risk associated with child abuse, however, may override social sanctions against substance use and result in increased substance use among women [13, 34].

Our findings suggest that antenatal cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol use predict offspring LBW, which is consistent with the literature that links intrauterine exposure to tobacco and alcohol to LBW [35]. Intrauterine hypoxia is the most widely accepted mechanism by which tobacco smoking may result in fetal growth restriction [36]. The teratogenic effects of heavy alcohol use during pregnancy are well documented, including fetal growth restriction. However, less severe alcohol consumption, such that infants are exposed to 1 to 1.5 drinks a day, also increases risk for LBW [36]. Given the underestimation of self-reported alcohol and tobacco use in pregnancy, and the validity of retrospective assessment of childhood abuse [37], screening for childhood abuse may be an effective way to identify those women at risk for antenatal substance use.

The findings from this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we relied upon mother’s reports of birth weight. Verification from clinical records was not available. However, it has been shown that use of maternal recollection of offspring birth weight is a valid method of obtaining data when clinical verification is unavailable [38]. Second, we used retrospective reports of early-life maltreatment. Some researchers suggest that retrospective accounts may be biased to some extent on current psychological state [39]. However, current depression was tested and not shown to be a confounder in the present analyses. Third, we did not include assessments of G2’s own birth weight, as maternal birth weight has consistently been linked to offspring birth weight [40]. Finally, respondents in the present study were recruited from a community-based sample from a single geographic region. Results from this study may not generalize to other populations of women.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that the cumulative risk associated with low SES and maltreatment in childhood has implications for birth weight in children born in the next generation. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the pathways linking early-life maternal risk and offspring birth weight. We acknowledge that prenatal care is an important component of women’s reproductive health. However, these findings suggest that important risks associated with offspring birth weight also occur during the early-life of the mother. Policy and clinical interventions must be designed and implemented to reduce child poverty and child maltreatment, as well as to screen and address the consequences of child maltreatment during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1KL2RR025015-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research and grants R01DA009679-(01-13), and 5R01DA023089-(01-02) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Competing Interest

None

Contributors

Amelia R. Gavin conceived and designed the study and wrote the article. Karl G. Hill assisted in study design and conducted the analysis and assisted in writing and editing the article. J. David Hawkins assisted in editing the article. Carl Maas assisted in conducting the analysis and editing the article. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CITATIONS

- 1.Goldenberg R, Culhane J. Low birth weight in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(suppl):584S–590S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.584S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarnoudse-Moens C, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever J, et al. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton B, Martin J, Ventura S. National vital statistics reports. 7. Vol. 57. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. Births: preliminary data for 2007. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins J, David R, Prachand N, et al. Low birth weight across generations. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7:229–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1027371501476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu M, Kotelchuck M, Culhane J, et al. Preconception care between pregnancies: The content of internatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2006;16:107–122. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer B, Milluzzi C, Collin M. Periviable birth at 20 to 26 weeks of gestation: proximate causes, previous obstetric history and recurrence risk. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1175–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S163–S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colen C, Geronimus A, Bound J, et al. Maternal upward mobility and black-white disparities in infant birthweight. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2032–2039. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hypponen E, Power C, Davey Smith G. Parental growth at different life stages and offspring birthweight: an intergenerational cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18:168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Chen E, Matthews KA. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1186:37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall-Tackett K. The health effects of childhood abuse: four pathways by which abuse can influence health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topitzes J, Mersky J, Reynolds A. Child maltreatment and adult cigarette smoking: a long-term developmental model. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009:1–15. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson H, Widom C. A prospective examination of the path from child abuse and neglect to illicit drug use in middle adulthood: the potential mediating role of four risk factors. J Youth Adolescence. 2009;38:340–354. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widom C, White H, Czaja S, et al. Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on alcohol use and excessive drinking in middle adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:317–326. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lansford J, Dodge K, Pettit G, et al. Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreat. 2009:1–15. doi: 10.1177/1077559509352359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gladstone G, Parker G, Mitchell P, Malhi G, Wilhelm K, Austin M. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–1425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyllstrom M, Hellerstedt, McGovern P. Independent and interactive associations of prenatal mood and substance use with infant birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2010:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham JW, Hofer . Multiple imputation in multivariate research. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multi-group data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. 201–218. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 2000. pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards, et al. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatrics. 2003;3:6–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lengua L, Sadowski C, Friedrich W, et al. Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children’s symptomatology: expert ratings and confirmatory factor analyses of the CBCL. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:683–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crane J, White J, Murphy P, et al. The effect of gestational weight gain by body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynecol Ca. 2009;31:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL. NIMH Diagnostic interview schedule: Version III. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; May, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffee S, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Fombonne, et al. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:215–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbuckle JL. Amos 18 User's Guide. Chicago: SmallWaters; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Astone N, Misra D, Lynch C. The effect of maternal socio-economic status throughout the lifespan on infant birthweight. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chrousos G, Gold P. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren W, Patrick S, Goland R. Elevated maternal plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone levels in pregnancies complicated by preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1198–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90606-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobel C, Dunkel-Schetter C, Roesch S, et al. Maternal plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone is associated with stress at 20 weeks gestation in pregnancies ending in preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Jan;180(1 Pt 3):S257–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadhwa P, Garite J, Porto M, et al. Placental corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), spontaneous preterm birth, and fetal growth restriction: a prospective investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney ER. Childhood victimization: relationship to adolescent pregnancy outcome. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:569–575. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widom C, Marmorstein N, White H. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith L, LaGasse L, Derauf C, et al. The infant development, environment, and lifestyle study: effects of prenatal methamphetamine exposure, polydrug exposure, and poverty on intrauterine growth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1149–1156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiriboga C. Fetal alcohol and drug effects. Neurologist. 2003;9:267–279. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000094941.96358.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paivio S. Stability of retrospective self-reports of child abuse and neglect before and after therapy for child abuse issues. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1053–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomeo CA, Rich-Edward J, Michel KB, et al. Reproductively and validity of maternal recall of pregnancy-related events. Epidemiology. 1999;10:774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widom CS, Raphael KG, DuMont KA. The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004) Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(7):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emanuel I, Kimpo C, Moceri V. The association of maternal growth and socio-economic measures with infant birthweight in four ethnic groups. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1236–1242. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]