Abstract

Background

Patients with ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential (OSLMP) who have peritoneal implants, especially invasive implants, are at increased risk of developing tumor recurrence. The ability of peritoneal washing (PW) cytology, to detect the presence and type of peritoneal implants has not been adequately investigated, and its prognostic significance is unknown.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed records and PW specimens of 101 patients diagnosed with and treated for OSLMP between 1996 and 2010 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. We compared patients’ staging biopsy findings with those of our review of the PWs. Follow-up data were also analyzed.

Results

Of the 96 patients with staging biopsy results available, 26 (27%) had peritoneal implants (17 noninvasive, 9 invasive), 19 (20%) had endosalpingiosis, and 51 (53%) had negative findings. The PW specimens of 18 of the 26 patients (69%) with peritoneal implants were positive for serous neoplasm, and a correlation was found between cytologic and histologic findings (p < 0.0001). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, and negative predictive values were 69%, 84%, 62% and 88%, respectively. Four of 101 patients had disease recurrence, 3 of these patients had invasive implants and 1 patient had noninvasive implants. None of the patients who had negative staging biopsy findings or endosalpingiosis but PW specimens positive for serous neoplasm developed disease recurrence.

Conclusions

PW cytology detects the presence of peritoneal implants with moderate accuracy. Long-term studies are needed to determine whether positive PW cytologic findings are an independent predictor of tumor recurrence.

Introduction

An ovarian serous neoplasm of low malignant potential (OSLMP) is defined as a tumor exhibiting atypical epithelial proliferation without destructive stromal invasion. These tumors constitute between 10% and 20% of ovarian serous tumors, and up to 90% of patients with OSLMP have a very favorable prognosis, although 10% exhibit a recurrent clinical course with peritoneal implants and, occasionally, die from the tumor [1, 2].

Up to 30% of patients who present with OSLMP tumors also present with extraovarian disease. These lesions are classified as either invasive or noninvasive implants using strict histologic criteria. The type of implant is meaningful prognostically as a predictor of disease outcome and clinically as an indicator of which patients may require additional therapy. Patients who have noninvasive implants have a significantly lower lifetime risk of relapse and disease-related mortality than do those with invasive implants. The clinical course for patients with invasive implants closely resembles that of patients with low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC), with increased relapse rates and disease-related mortality rates approaching 30% in some studies [2, 3]. Surgical staging for the implants is therefore recommended, although the extent of evaluation necessary remains controversial.

Since the 1950s, peritoneal washing (PW) cytology has been used to evaluate gynecologic cancers, and in 1975 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) included PW cytology as part of the staging procedure for ovarian carcinomas [4]. The presence of malignant cells in PW cytologic specimens raises the FIGO stage from IA/IB or IIA/IIB to IC or IIC for ovarian carcinoma. Although histologic sampling of peritoneal surfaces is the gold standard for determining the extent of peritoneal tumor involvement, published studies have demonstrated that PW cytology is also fairly sensitive and highly specific for peritoneal implants [5–7]. As such, PW cytology is part of routine practice in managing patients with ovarian neoplasms of all grades, either during initial evaluation or second-look procedures [8].

Although most studies examining PW cytology and peritoneal tumor involvement have included patients with OSLMP in their analyses, the proportion of such patients was too small for a meaningful result [5, 9–11]. One study involved a relatively large number of patients with OSLMP and found a strong relationship between PW cytologic findings and peritoneal implants in general, but it did not examine PW cytologic findings as they relate to the type of implants (invasive, noninvasive, or endosalpingiosis), and follow-up data were not given [11].

In this study, we evaluated the ability of PW cytology to predict the presence and type of peritoneal implants in patients with OSLMP, and we examined the prognostic significance of PW cytologic findings in terms of long-term disease recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We used an institutional electronic medical records database at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center to identify patients with a diagnosis of OSLMP who underwent primary surgical resection of their tumors at MD Anderson between January 1996 and July 2010. We recorded patient age, surgical (histologic) diagnosis of the primary tumor, peritoneal tumor staging biopsy histologic findings (if available), and follow-up information (i.e., treatment; disease recurrence, which was documented by surgical biopsy; and death from disease or other causes), and we reviewed the PW cytologic specimens used for staging for each patient. Patients who had other malignant tumors of the ovary, uterus, or other sites and those whose PW cytologic specimens were not available for review were excluded from analysis. This study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board (Protocol Lab PA11-0964).

Surgical diagnoses fell into 4 general categories according to quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the ovarian tumor (listed here from least to greatest severity): 1) OSLMP arising from serous cystadenofibroma, defined in our surgical practice as tumors with less than 10% OSLMP; 2) OSLMP, with characteristic papillary structures lined by a tubal-type epithelium with cellular detachment and “tufting”; 3) OSLMP with microinvasion, defined as invasion less than 3 mm in any dimension; and 4) OSLMP with micropapillary features (length of papillary tufts greater than 5 times the width).

Almost all patients included in the study underwent a staging procedure for peritoneal implants beyond PW cytology. Some staging procedures were limited to omentectomy, but most patients underwent full staging, including peritoneal biopsies and lymph node sampling. Staging biopsy results of peritoneal implants were categorized as negative, endosalpingiosis, noninvasive implant, or invasive implant, using established histologic criteria (1).

Cytologic Specimens

All PW cytologic specimens reviewed in this study had been collected at the time of surgery using the following technique. Upon opening the peritoneal cavity, the surgeon aspirated any free fluid. If free fluid was absent, areas of the peritoneal surface were lavaged with 50–100 mL of warm physiologic saline solution and submitted as either multiple or single specimens to the cytopathology laboratory. Four cytospin smears were prepared and stained by the Papanicolaou method following fixation in modified Carnoy’s solution.

For our study, these specimens were reviewed by 2 of the authors (N.S. and J.B.T.), who classified the specimens as negative, endosalpingiosis, or serous neoplasm, without knowledge of the surgical staging biopsy findings, using criteria adapted from previously published reports [9, 10,12–15]. If multiple specimens were obtained for 1 patient, the final cytologic classification for that patient was based on the specimen with the highest abnormal findings. Given the fact that invasive implants are morphologically similar to LGSC, and the difficulties in distinguishing between OSLMP and LGSC tumors in cytologic preparations [9], the diagnosis of serous neoplasm, not further characterized, was chosen to encompass both invasive and noninvasive implants.

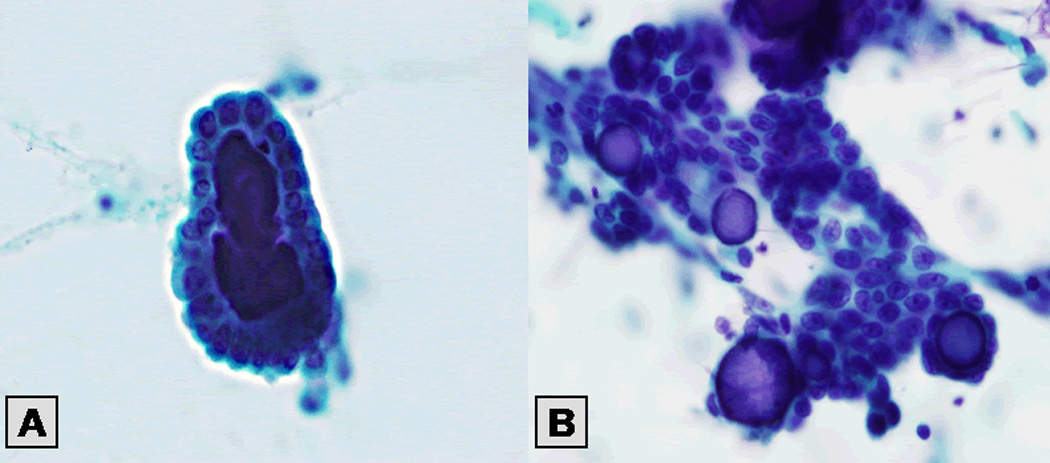

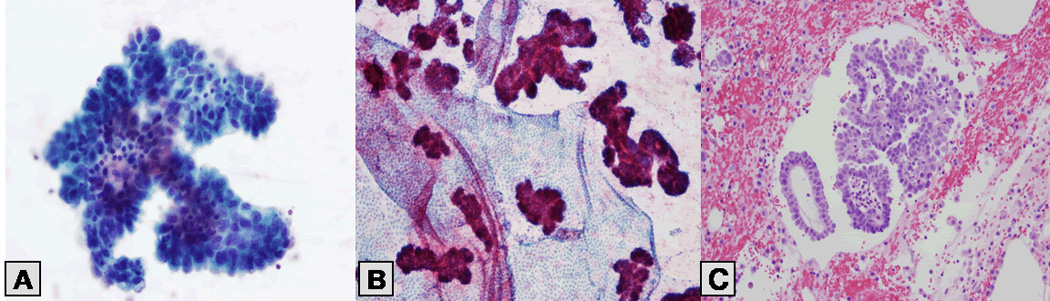

Endosalpingiosis (or Müllerian metaplasia) was recognized by the presence of a second distinct cell population consisting of cuboidal to columnar or cylindrical cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm, sometimes with cilia, and eccentric oval nuclei with fine granular chromatin and round nucleoli. The cells were often arranged in simple, smoothly contoured groups, with occasional non-branching papillary formations; the groups lacked intercellular windows and surrounded 1 or more psammoma bodies. Cytologic atypia were mild to moderate, and the number of cell groups was often less than 20. In contrast, a complex architectural or papillary arrangement of the cell groups, moderate to severe cytologic atypia, or atypical cell groups numbering more than 20 were features characterizing serous neoplasm [9,10,12–15].

Statistical Analysis

We used Fisher’s exact test to examine the relationship between the surgical diagnosis of the primary tumor and the peritoneal implant status as determined by staging biopsy and by our review of the PW cytologic specimens, as well as between staging biopsy results and PW cytologic findings. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Considering the surgical biopsy staging findings as the gold standard, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, and negative predictive values of the PW cytologic findings in detecting peritoneal implants were also calculated. Since endosalpingiosis is considered a benign process, this category was grouped with the negative findings.

Results

We reviewed the records of 101 patients, ranging in age from 21 to 89 years at diagnosis, for this study; a total of 147 PW cytologic specimens for these patients were examined.

Histologic findings of the ovarian tumors in the 101 patients revealed 38 cases of OSLMP arising from serous cystadenofibroma, 34 OSLMP, 20 OSLMP with microinvasion, and 9 OSLMP with micropapillary features (2 of which also showed microinvasion). Staging biopsy findings were available for 96 patients, and these showed peritoneal implants in 26 patients (27%; 17 noninvasive, 9 invasive) and endosalpingiosis in 19 patients (20%); the remaining 51 patients (53%) had negative biopsy findings. Of the 5 unstaged patients, 4 had OSLMP arising from serous cystadenofibroma, and 1 had OSLMP with microinvasion. A significant association was found between the type of primary ovarian tumor and peritoneal implant status as determined by staging biopsy (p < 0.0001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Peritoneal tumor implants by extent/degree of ovarian tumor (96 Cases)

| Staging biopsy findings |

CAF with focal OSLMP |

OSLMP | OSLMP with Microinvasion |

OSLMP with micropapillary features |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 24 | 16 | 7 | 4 | 51 |

| Endosalpingiosis | 8 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 19 |

| Noninvasive implants | 2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| Invasive implants | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| Total | 34 | 34 | 19 | 9 | 96 |

Abbreviations: CAF- Serous cystadenofibroma; OSLMP- Ovarian serous tumor of low malignant potential; 5 cases (4 CAF with OSLMP, and one OSLMP with microinvasion) had no available biopsy staging

PW cytologic findings were as follows: serous neoplasm in 29 patients (29%), endosalpingiosis in 21 patients (21%), and negative findings in 51 patients (50%; Figs. 1 and 2). The type of primary ovarian tumor was not related to peritoneal implant status as determined by PW cytology (p = 0.0583; Table 2); however, a significant association was found between PW cytologic findings and staging biopsy findings (p < 0.0001; Table 3).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Table 2.

Peritoneal washing cytology by extent/degree of ovarian tumor (101 Cases)

| Peritoneal Washing Cytology |

CAF with focal OSLMP |

OSLMP | OSLMP with Microinvasion |

OSLMP with micropapillary features |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 26 | 14 | 9 | 2 | 51 |

| Endosalpingiosis | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 21 |

| Serous Neoplasm | 6 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 29 |

| Total | 38 | 34 | 20 | 9 | 101 |

Abbreviations: CAF-Serous cystadenofibroma; OSLMP-Ovarian serous tumor of low malignant potential.

Table 3.

Peritoneal tumor implants versus peritoneal washing cytology (96 Cases)

| Tumor Implants | Negative | Endosalpingiosis | Serous Neoplasm | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 33 | 12 | 6 | 51 |

| Endosalpingiosis | 10 | 4 | 5 | 19 |

| Noninvasive implant | 2 | 2 | 13 | 17 |

| Invasive implant | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 |

| Total | 47 | 20 | 29 | 96 |

5 cases (4 CAF with OSLMP, and one OSLMP with microinvasion) had no available biopsy staging

The PW cytologic specimens of 18 of the 26 patients (69%) with invasive and noninvasive peritoneal tumor implants were positive for serous neoplasm (Table 3). The percentage of PW specimens positive for serous neoplasm was higher in patients with noninvasive implants than in patients with invasive implants [13/17 (76%) vs 5/9 (56%), respectively]. However, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.382). In the 51 patients with negative biopsy findings, 6 (12%) had PW cytologic findings positive for serous neoplasm, and in the 19 patients with endosalpingiosis, 5 (26%) had PW cytologic findings positive for serous neoplasm. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive values of PW for detecting peritoneal implants were 69%, 84%, 62%, and 88%, respectively.

All 101 patients were followed for a period ranging from 6 months to 168 months (mean 58.8 months, median 48 months). Only patients whose staging biopsy showed invasive implants received chemotherapy as part of the treatment protocol. In 4 of the 101 patients, tumor recurrence was detected 16 to 120 months after diagnosis (median time to recurrence, 36 months; Table 4). Three recurrences were in patients with invasive implants, and 1 recurrence was in a patient with noninvasive implants. None of the patients who had negative staging biopsy findings or endosalpingiosis but PW cytologic specimens positive for serous neoplasm developed disease recurrence during their follow-up period. Of the 101 patients, 88 were alive at last follow-up, 7 were lost to follow-up, and 6 had died, 1 of whom died from her disease.

Table 4.

Summary data of patients with recurrent disease

| Patient Number |

AGE | Ovary Tumors |

Implants | Peritoneal Washing Cytology |

RECURRENCE from time of diagnosis (years) |

Bx Site |

OUTCOME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | OSLMP | Invasive | Negative | 7 | pelvis | D |

| 2 | 30 | OSLMP, MI | Invasive | SN | 10 | lung | A |

| 3 | 31 | OSLMP | Invasive | Negative | 2 | Abdominal, LMP, non inv | A |

| 4 | 27 | OSLMP | Non-Invasive | SN | 16 months | contralateral ovary | A |

Abbreviations: D- deceased from other causes; OSLMP- Ovarian serous tumor of low malignant potential; MI- microinvasion, SN- serous neoplasm.

This patient had initially a salpingo-oophorectomy of one ovary with limited staging. She developed recurrence in the remaining ovarian tissue. She is NED at time of follow up (4 yrs after her second surgery).

Discussion

We found that PW cytology was a relatively sensitive indicator of the presence of peritoneal implants in patients with OSLMP, with a sensitivity score of 69%, although it could not distinguish between invasive and noninvasive implants. Few patients experienced tumor recurrence; however, most of those who did also had invasive implants, indicating that long-term follow-up of patients is needed to determine whether positive PW cytologic findings are an independent predictor of tumor recurrence.

In our study, the overall rate of PW specimens positive for serous neoplasm (29%) is similar to rates reported by others (range 31%–38%) [5,11,16]. Only 1 study, of 14 patients, reported a much lower rate (7%) of PW cytologic specimens positive for serous neoplasm [17]. Moreover, in our study, PW cytologic findings were associated with staging biopsy findings: 69% of PW cytologic specimens positive for serous neoplasm were from patients with peritoneal implants. Similar findings were reported by Zuna and Behrens [5].

Two other studies reported sensitivity rates of 80% and 90%, which are higher than the 69% sensitivity rate found in our study [11, 16]. However, none of the previous studies have included in their analysis a category of endosalpingiosis, indicating that this category was grouped either with the negative cases or, more likely, with the positive cases, which would result in a higher sensitivity rate for PW cytology than was found in our analysis. In addition, the inclusion of patients with other ovarian tumors, such as mucinous ovarian tumors of low malignant potential, that were associated with higher rates of positive PW specimens (44% in the study by Cheng et al [11]) than were other types of tumors may also have contributed to increased sensitivity rates in these studies.

Notably, 6 of 51 patients in our study whose staging biopsy was negative for peritoneal implants and 5 of 19 of those whose staging biopsy indicated endosalpingiosis (11/70, or 16% overall) were found to have PW cytologic specimens positive for serous neoplasm. In a study by Cheng et al, the rate of PW cytologic specimens positive for serous neoplasm in patients without peritoneal implants was even higher (23%) than the rate we found [11]. Whether these cytologic findings represent foci of undetected extraovarian neoplasm or are due to inherent problems in the cytomorphologic evaluation of these specimens is difficult to determine.

The significance of positive PW specimens in patients whose staging biopsies were negative for implants is unknown. In one study, late recurrences were reported in patients with OSLMP whose staging biopsies were negative for implants but positive for endosalpingiosis [18]. Although it is likely that some of the negative biopsies were due to sampling errors at the site of the implants [18], these findings suggest that any positive PW cytologic findings, even for endosalpingiosis, may indicate an increased risk for tumor recurrence. Because no long-term follow-up data on the significance of positive PW specimens in patients with early-stage OSLMP are available, close follow-up of patients with PW cytologic findings positive for serous neoplasm is warranted to determine the prognostic significance of PW cytology.

It is well established that patients with OSLMP can have recurrences more than 10 years after the initial diagnosis, and thus long-term follow-up is recommended. However, the median follow-up time for patients in our study was only 4 years, and although our follow-up data demonstrate the generally favorable prognosis of these tumors, with more than 98% of patients diagnosed over the period studied surviving their disease, 4 patients did experience tumor recurrence. These patients had known predictors of poor prognosis, i.e., invasive implants (3 patients) or OSLMP with microinvasion (1 patient). Only 1 patient whose surgical biopsy was positive for noninvasive implants developed tumor recurrence. However, it is likely that sampling error of the invasive component led to underestimation of the biopsy findings, or perhaps biologic features of aggressive behavior were present but were not detected.

In conclusion, PW cytology is a relatively sensitive indicator of the presence of peritoneal implants and may detect a subset of patients with subclinical peritoneal involvement, although no cytologic features exist to accurately distinguish between invasive and noninvasive peritoneal implants. Although tumor recurrence primarily occurs in OSLMP patients with invasive implants, long-term follow-up of patients with any positive PW cytologic findings is warranted because of the potential for long-term recurrence, and also to determine whether positive PW cytologic findings are an independent predictor of tumor recurrence.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by a Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Denkert C, Dietel M. Borderline tumors of the ovary and peritoneal implants. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 2005;89:84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong KK, Gershenson D. The continuum of serous tumors of low malignant potential and low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary. Dis Markers. 2007;23(5–6):377–387. doi: 10.1155/2007/204715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seidman JD, Kurman RJ. Ovarian serous borderline tumors: a critical review of the literature with emphasis on prognostic indicators. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):539–557. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuna RE, Behrens A. Peritoneal washing cytology in gynecologic cancers: long-term follow-up of 355 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(14):980–987. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.14.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravinsky E. Cytology of peritoneal washings in gynecologic patients: diagnostic criteria and pitfalls. Acta Cytol. 1986;30:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimura S, Scully RE, Taft PTD, Herrington JB. Peritoneal fluid cytology in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;17:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(84)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copland LJ, Silva EG, Gershenson DM, Sneige N, Atkinson EN, Wharton JT. The significance of Mullerian inclusions found at second-look laparotomy in patients with epithelial ovarian neoplasms. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:763–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weir MM, Bell DA. Cytologic identification of serous neoplasms in peritoneal fluids. Cancer. 2001;93(5):309–318. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadeghi S, Ylagan LR. Pelvic washing cytology in serous borderline tumors of the ovary using ThinPrep: are there cytologic clues to detecting tumor cells? Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;30(5):313–319. doi: 10.1002/dc.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng L, Wolf NG, Rose PG, et al. Peritoneal washing cytology of ovarian tumors of low malignant potential: correlation with surface ovarian involvement and peritoneal implants. Acta Cytol. 1998;42(5):1091–1094. doi: 10.1159/000332094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sneige N, Fernandez T, Copeland LJ, et al. Mullerian inclusions in peritoneal washings. Potential source of error in cytologic diagnosis. Acta Cytol. 1986;30(3):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sneige N, Fanning CV. Peritoneal washing cytology in women: diagnostic pitfalls and clues for correct diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992;8(6):632–642. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840080621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shield P. Peritoneal washing cytology. Cytopathology. 2004;15(3):131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2004.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covell JL, Carry JB, Feldman PS. Peritoneal washings in ovarian tumors. Potential sources of error in cytologic diagnosis. Acta Cytol. 1985;29(3):310–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fadare O, Mariappan MR, Wang S, Hileeto D, McAlpine J, Rimm DL. The histologic subtype of ovarian tumors affects the detection rate by pelvic washings. Cancer. 2004;102:150–156. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozkara SK. Significance of peritoneal washing cytopathology in ovarian carcinomas and tumors of low malignant potential: a quality control study with literature review. Acta Cytologica. 2011;55:57–68. doi: 10.1159/000320858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva EG, Tornos C, Zhuang Z, Merino M, Gershenson DM. Tumor recurrence in stage I ovarian serous neoplasms of low malignant potential. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]