Abstract

The ability of each cell within a metazoan to adapt to and survive environmental and physiological stress requires cellular stress-response mechanisms, such as the heat shock response (HSR). Recent advances reveal that cellular proteostasis and stress responses in metazoans are regulated by multiple layers of intercellular communication. This ensures that an imbalance of proteostasis that occurs within any single tissue ‘at risk’ is protected by a compensatory activation of a stress response in adjacent tissues that confers a community protective response. While each cell expresses the machinery for heat shock (HS) gene expression, the HSR is regulated cell non-autonomously in multicellular organisms, by neuronal signaling to the somatic tissues, and by transcellular chaperone signaling between somatic tissues and from somatic tissues to neurons. These cell non-autonomous processes ensure that the organismal HSR is orchestrated across multiple tissues and that transmission of stress signals between tissues can also override the neuronal control to reset cell- and tissue-specific proteostasis. Here, we discuss emerging concepts and insights into the complex cell non-autonomous mechanisms that control stress responses in metazoans and highlight the importance of intercellular communication for proteostasis maintenance in multicellular organisms.

KEY WORDS: Caenorhabditis elegans, Chaperones, Proteostasis, Stress response, Cell non-autonomous, Metazoans

Introduction

The maintenance of a highly functioning proteome is an ever-present challenge throughout the life of every cell and therefore crucial for its optimal function and cellular viability. Although the information required for the folding of a polypeptide into a functional 3-dimensional stable conformation is encoded in the primary sequence of the protein (Anfinsen, 1973), folding efficiency and stability are challenged by the appearance of multiple on- and off-pathway intermediates, and a crowded cellular environment (Ellis and Minton, 2006). Moreover, protein folding and stability are strongly influenced by mutations within the coding sequence, error-prone synthesis, and the compromising effects of acute and chronic cell stress conditions, aging, pathology and disease. Consequently, to prevent the mismanagement of the proteome, leading to misfolding and aggregation, every cell expresses a complex network of quality control mechanisms, the proteostasis network, for efficient protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, secretion and degradation (Balch et al., 2008).

When challenged, the proteostasis network faces a daunting task to maintain protein quality control and a balanced proteome. Studies with unicellular organisms and isolated tissue cells in culture have shown that each cell can respond cell autonomously to stress conditions by activation of the heat shock response (HSR). For metazoans composed of tissues with thousands to trillions of cells, the question is whether cellular stress responses are coordinated across tissues through additional levels of regulation to maintain balance during development, adulthood and aging, and in response to metabolic and environmental stress. For example, if a single tissue or organ experiences a proteotoxic challenge, does this tissue respond alone and independent of neighboring tissues, or is the stress sensed by adjacent cells and tissues, leading to organism-wide consequences?

Recent advances on the regulation of cell stress responses at the organismal level now show that proteostasis maintenance of individual cells can be regulated by direct communication between different cell types, such as signaling from neurons to somatic tissues, between somatic tissues, and between somatic tissues to neurons (Garcia et al., 2007; Prahlad et al., 2008; Durieux et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2012; Taylor and Dillin, 2013; van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). In this review, we will discuss recent findings and emerging concepts that focus on organismal stress responses between and across tissues.

Maintaining proteome integrity by cellular stress responses

The HSR

Chronic proteotoxic stress inevitably leads to the accumulation of misfolded or aggregated proteins that result in the induction of the HSR and elevated expression of heat shock (HS) proteins, many of which function as molecular chaperones. Increased levels of chaperones have been shown to be highly protective against a wide range of proteotoxic conditions by restoring the folding and function of regulatory proteins that are essential for the re-establishment of proteostasis and cellular function. This is primarily controlled by the master regulator of the HSR, which in eukaryotes is heat shock transcription factor HSF-1. HSF-1 functions as a rheostat for acute stress, to prevent cell death, and monitors chronic proteotoxic stress that affects fecundity and lifespan (Abravaya et al., 1991; Morley and Morimoto, 2004; Åkerfelt et al., 2010; Lindquist and Kelly, 2011; McMullen et al., 2012). HSF-1 is a highly conserved member of the HSF gene family that is constitutively expressed and negatively regulated in most cell types in the absence of stress (Åkerfelt et al., 2010). The activation of HSF-1 depends on many regulatory mechanisms including interaction with a multi-chaperone complex (Abravaya et al., 1992; Shi et al., 1998; Zou et al., 1998), post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation (Kline and Morimoto, 1997; Holmberg et al., 2001; Guettouche et al., 2005), sumolyation (Hietakangas et al., 2003; Anckar and Sistonen, 2007) and acetylation (Westerheide et al., 2009). These modifications influence the formation of HSF-1 trimers (Baler et al., 1993; Sarge et al., 1993), nuclear localization, and high-affinity binding of HSF-1 to consensus HS elements in the promoter region of target genes. The HSF-1 activation and attenuation cycle is strongly dependent on the concentration of specific cytoplasmic chaperones. For example, high constitutive levels of the chaperone Hsp90 prevent HSF-1 trimerization from its inactive monomeric state (Ali et al., 1998; Zou et al., 1998), whereas HS results in dissociation of this complex and conversion of inert HSF-1 monomers to the high-affinity DNA-binding trimers. The duration and intensity of HSF-1 activation is therefore proportional to the expression of chaperones. In this negative feedback mechanism, elevated levels of chaperones attenuate HSF-1 activity (Shi et al., 1998), which together with acetylation in the HSF-1 DNA-binding domain (Westerheide et al., 2009) provides multiple regulatory steps for both transcriptional attenuation and release of HSF-1 from the promoter element of the HS genes.

Compartmental stress responses: the UPRER and the UPRmt

The functional complement to the HSR in the organelles is the unfolded protein response (UPR) that serves in a similar role to prevent misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum (UPRER) and in mitochondria (UPRmt). The ER is the primary site for synthesis and modification of membrane and secretory pathway proteins. Activation of the UPRER is triggered when unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER and exceed the folding capacity of the lumen chaperones including BiP/GRP78, GRP94, calnexin, calreticulin and PDI. To compensate, the three canonical branches of the UPRER are induced by three distinct ER stress-response factors: IRE1, PERK and ATF6. Each of these ER stress-response factors activates a distinct downstream signal transduction pathway that increases the ER capacity to counteract protein misfolding (Ron and Walter, 2007). PERK phosphorylates translation initiation factor 2 to attenuate protein synthesis, leading to reduced flux of nascent chains in the ER during stress. Activated ATF6 translocates to the Golgi, where it forms an active transcription factor that enters the nucleus to upregulate the transcription of ER chaperone proteins. IRE1 activates the transcription factor XBP-1 through splicing, which transcribes genes involved in ER homeostasis, export and degradation of misfolded proteins (Schröder and Kaufman, 2005; Ron and Walter, 2007). Interestingly, genes upregulated by the HSF-1-dependent HSR can overlap with some UPR targets and have been suggested to crosstalk during stress to promote cellular survival (Liu and Chang, 2008).

Analogous to the HSR and the UPRER, the UPRmt senses and responds to the level of damaged proteins that accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix. Misfolded proteins are degraded by the matrix protease ClpXP, and are transported to the cytosol by the peptide transporter HAF1, which in turn activates the transcription factor ATFS-1 (ZC367.7) to translocate into the nucleus and induce the transcription of mitochondrial chaperones (Haynes and Ron, 2010; Nargund et al., 2012).

Although these cellular stress responses have been thought to be induced in a strict cell-autonomous manner, recent advances now demonstrate that the cytoplasmic HSR, the UPRER and the UPRmt are all regulated by cell non-autonomous control in Caenorhabditis elegans, as will be discussed in the following sections.

Perceiving environmental stress: regulation of proteostasis via neuronal signaling

In metazoans, stress-responsive signaling is a combination of cell-autonomous and non-autonomous events that ensures cellular health across all tissues for overall organismal survival. Among these signaling pathways are neuroendocrine pathways, and neurosensory cues such as the insulin-like signaling (ILS) pathway in C. elegans, which influences longevity in response to different conditions (Cypser and Johnson, 2001; Alcedo and Kenyon, 2004; Baumeister et al., 2006). Although other neuroendocrine pathways such as the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway and the nuclear hormone receptor (NR) pathway have the capability to modulate stress tolerance, the ILS pathway has gained most attention over the past years (Prahlad and Morimoto, 2009). High temperature, starvation and oxidative stress are conditions shown to inhibit this signaling cascade, leading to de-phosphorylation of the transcription factor DAF-16 and its subsequent translocation into the nucleus where it upregulates the transcription of heat shock- and other stress-inducible genes (Baumeister et al., 2006; Samuelson et al., 2007). Moreover, the ILS pathway not only requires DAF-16 but also depends on HSF-1 function (Morley and Morimoto, 2004). Interestingly, HSF-1 itself can be regulated by ILS via interaction with a DDL-1/DDL-2-containing protein complex (Hsu et al., 2003; Chiang et al., 2012).

Cell non-autonomous stress responses regulated by neurons in C. elegans

The biological detection of temperature relies on receptor proteins, represented by the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel protein family (Caterina et al., 1997; Clapham, 2003; Voets et al., 2004; Gallio et al., 2011), which directs the temperature signal to a signaling cue that initiates a cellular response. In C. elegans, TRP channels that respond to different environmental cues have been identified (Xiao and Shawn Xu, 2011). However, only the cold-sensitive TRPA-1 channel functions as a thermo-responsive TRP channel in C. elegans (Xiao et al., 2013).

Environmental changes in C. elegans are also perceived through specialized sensory neurons (Mori, 1999; de Bono and Maricq, 2005) and fluctuations of ambient temperature are sensed through two thermosensory AFD neurons (Mori et al., 2007). Input from the AFD neurons regulates temperature-dependent growth and behavior, and mutations in the AFD-specific receptor-type guanylyl cyclase gcy-8 have been shown to disrupt thermotaxis behavior (Inada et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2007; Lee and Kenyon, 2009).

A link between thermosensory neuronal control and the HSR was demonstrated using mutations in gcy-8 and other AFD-specific null mutations that were shown to be deficient in the HSF-1-dependent regulation of the HSR (Prahlad et al., 2008). When thermosensory gcy-8 mutants were challenged by an acute HS treatment, the HSF-1-dependent HSR was blocked across multiple tissues of the animal, leading to reduced thermotolerance (Prahlad et al., 2008). Although it was shown previously that neuronal input at the synaptic junction regulates protein homeostasis in post-synaptic muscle cells of C. elegans (Garcia et al., 2007), the observation by Prahlad and colleagues provided the first evidence for a cell non-autonomous control of HSF-1 transcriptional activity through a neurosensory input. This ultimately led to the realization that stress responses and maintenance of proteostasis in multicellular organisms must be orchestrated cell non-autonomously through a centralized control. While the effector of AFD-dependent signaling in response to heat is HSF-1, the signaling pathway and molecules that transduce this signal remain to be fully identified (Fig. 1). Different neurosensory inputs induce different stress responses, because the HSF-1-dependent response to heavy metal stress, which is perceived through chemosensory neurons, remained stress responsive in AFD-deficient animals (Prahlad et al., 2008). Moreover, the AFD signal(s) appears to be critical for the response to acute heat stress but not for chronic proteotoxic stress, as AFD-deficient animals could activate the HSR leading to suppression of protein aggregation in peripheral tissues (Prahlad and Morimoto, 2011). In this regard, it is of interest to note that AFD neurons also affect lifespan by controlling the nuclear hormone receptor DAF-12 through steroid signaling (Lee and Kenyon, 2009).

Fig. 1.

Cell non-autonomous control of the heat shock response (HSR) by neurons. Organismal control of heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF-1) transcriptional activity in peripheral tissues by the thermosensory AFD neuron via a guanylyl cyclase GCY-8-dependent signaling cascade. A steroid signalling-dependent feedback loop from peripheral cells reports HSR activity back to the AFD neurons.

Remarkably, HSF-1 activity in peripheral tissues influences thermosensory neurons in a reverse feedback that alters thermotactic behavior in C. elegans (Fig. 1). This HSF-1-dependent signaling reports on temperature changes in non-neuronal cells to the nervous system, and is regulated by estrogen signaling through NHR-69 activity in AFD neurons (Sugi et al., 2011). The relationship between AFD-dependent coordination of the HSR in peripheral cells and AFD-dependent endocrine signaling involved in lifespan regulation (Lee and Kenyon, 2009) or thermotaxis (Sugi et al., 2011) remains to be established.

A comparable feedback loop exists in Drosophila where somatic tissues report transcriptional changes to neurons: transgenic FOXO activity in muscle cells leads to reduced insulin expression and secretion from neurosecretory cells, resulting in decreased feeding behavior. This feedback mechanism from muscle tissues to neurons in Drosophila involved the systemic activation of FOXO through the ILS pathway, and resulted in enhanced organismal proteostasis and lifespan (Hwangbo et al., 2004; Demontis and Perrimon, 2010). Thus, activation of the neuronal circuitry through environmental signals and intrinsic physiological signals provides a feedback on proteostasis perturbations in specific cells.

Additional support for the role of the nervous system in the response to environmental stimuli to maintain organismal homeostasis was provided in studies that identified a neural circuit controlling innate immunity in C. elegans via the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) OCTR-1, expressed in ASH and ASI sensory neurons (Styer et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2012). OCTR-1 was shown to control the innate immune response to bacterial infections by negative regulation of pqn/abu genes in peripheral, non-neuronal tissue (Sun et al., 2011). This gene family is part of the non-canonical UPR pathway and is transcriptionally regulated by the apoptotic phagocytosis receptor CED-1. Whereas the OCTR-1-expressing sensory neurons regulate the non-canonical UPR during development, the classical IRE1/XBP1 UPR pathway is controlled by the same set of neurons in adult animals (Sun et al., 2012). Consistent with this, regulation of one of the canonical branches of the UPRER affects organismal stress signaling in C. elegans (Taylor and Dillin, 2013). In this study, a constitutively activated form of the UPRER stress factor XBP-1 (xbp-1s) in neurons was capable of restoring ER stress resistance in aged animals as well as extending lifespan. Neuronal xbp-1s expression also activated the UPRER in the intestine, which was dependent on the presence of functional ire-1 and xbp-1 in the receiving cells. These observations have led the authors to postulate that transmission of the stress signal from the neurons to the intestine may be achieved via an as-yet unidentified neurotransmitter (Taylor and Dillin, 2013).

Another example of cell non-autonomous regulation of stress responses in C. elegans is the UPRmt (Durieux et al., 2011). Neuron-specific knockdown of cco-1, a component of the electron transport chain, activates the UPRmt in peripheral tissues and thereby influences organismal survival. Although the mechanism by which the stress signal is transmitted in a cell non-autonomous manner is unclear, Durieux and colleagues proposed the existence of ‘mitokines’, signals that are generated in cells experiencing mitochondrial stress and that can be perceived by the entire animal (Durieux et al., 2011).

Proteostasis ‘crosstalk’ between somatic tissues

Neuronal signaling provides a rapid way to communicate vital information on cellular processes over long distances in multicellular organisms. From an evolutionary perspective, intercellular communication was also important to multicellular societies of unicellular organisms (Shapiro, 1998) in the absence of a complex centralized cellular control. Indeed, the ability of a cell to communicate with neighboring cells and sense their local microenvironment likely formed the basis for coordinated cellular activity in multicellular organisms. These include cell-to-cell communication methods in animal cells including cell junctions, adhesion contacts for soluble messengers, as well as the horizontal transfer of secreted microRNAs (miRNAs) packaged into exosomes or the exchange of cytoplasmic material via tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) (Singer, 1992; Denef, 2008; Kjenseth et al., 2010).

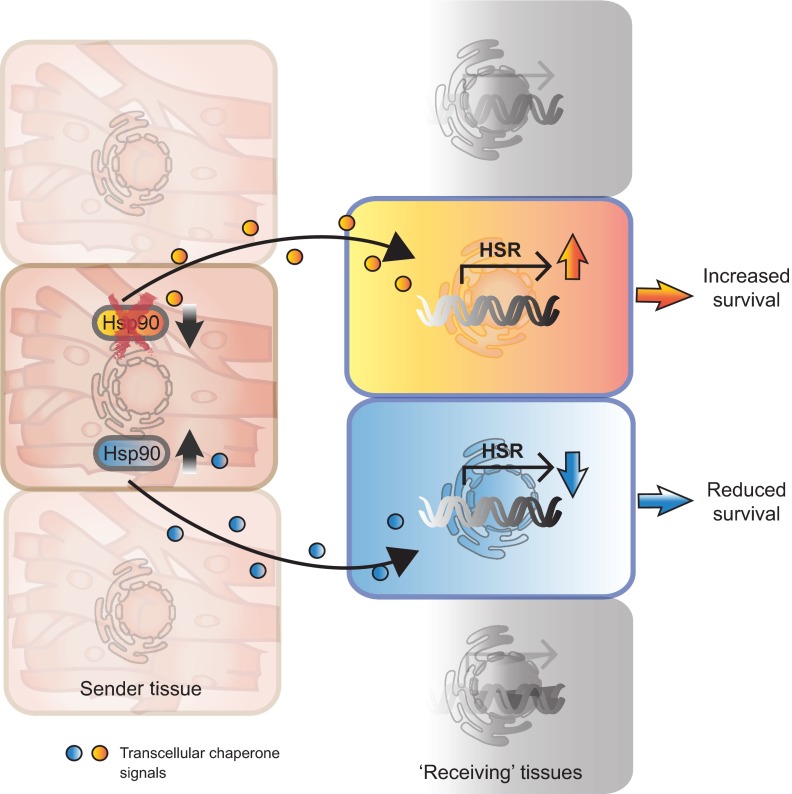

A recent observation in C. elegans reveals that non-neuronal regulated cell-to-cell communication, transcellular chaperone signaling, is essential for organismal proteostasis to ensure that stressed cells do not compromise the overall health of the organism (van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013). Thus, an imbalanced proteostasis network within a single tissue not only triggers a cell-autonomous protective response but also induces increased chaperone expression in adjacent (and distant) tissues to protect the organismal proteome. By this novel form of stress signaling, expression of a metastable myosin expressed in muscle leads to upregulation of muscle-autonomous hsp90 and a PHA-4-dependent transcriptional feedback that equalizes hsp90 expression among different tissues. This coordination among multiple tissues to provide an organism-level protection suggests that different cell types can function as sentinels to signal local proteotoxic challenges throughout the organism. How this integrative transcellular signaling affects the entire organismal response to environmental challenges is shown by imbalanced tissue-specific chaperone expression: while increased hsp90 expression can be beneficial for metastable proteins requiring a higher concentration of this chaperone, more severe environmental challenges could lead to a detrimental outcome due to repression of HSF-1-dependent HS proteins (van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Transcellular chaperone signaling regulates the organismal HSR via tissue-to-tissue crosstalk. An imbalance of proteostasis in a single tissue, through reduced (orange) or elevated (blue) expression of Hsp90, is detected and responded to in a different tissue via transcellular chaperone signaling. Because of the key role of Hsp90 as a negative regulator of the HSF-1-dependent HSR, the HSR is either induced (orange) or repressed (blue) at a cell non-autonomous level, leading to different outcomes for organismal survival during stress conditions.

Transcellular chaperone signaling, therefore, complements the neuronal control of the HSR, and peripheral tissues predisposed to transcellular chaperone signaling can override the neuronal influence leading to different outcomes for organismal survival. Even though the pathways that regulate transcellular chaperone signaling remain to be identified, the FoxA transcription factor PHA-4 appears to have a central role as an effector in stress signaling. PHA-4 activity is increased in the ‘donor tissue’, harboring an imbalanced proteostasis network, which influences PHA-4 activity in the ‘receiving tissues’, possibly via a signaling cascade or signaling molecule released from the donor tissue (van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013).

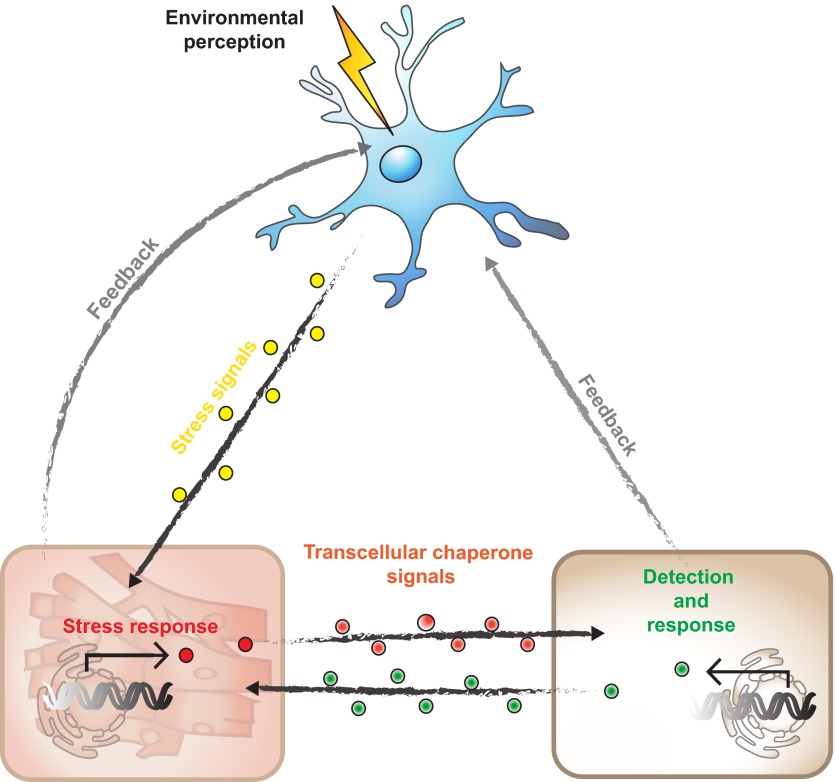

Together with observations on cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis via neuronal pathways, these studies reveal the importance for an organismal level of control. Thus, the proteostasis condition in one tissue can influence the proteostasis network in other tissues, and this cell non-autonomous process requires the exchange of signals that regulate the proteostasis network in the receiving tissues. Therefore, transcellular chaperone signaling complements the different neuronal cues that regulate organismal proteostasis, by providing an independent pathway to monitor the proteostasis condition between somatic tissues (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis via the nervous system and transcellular chaperone signaling. Sensory neurons perceive environmental stimuli and integrate the environmental challenge to fine-tune proteostasis in peripheral tissues. Non-neuronal tissues report altered proteostasis conditions back to the nervous system. At the same time, tissue-to-tissue signals via transcellular chaperone signaling can override the neuronal component to control cell-specific proteostasis. This allows proteostasis crosstalk between somatic cells independent of neural control.

Transfer of the stress signal: modes of intercellular communication in metazoans

An important question brought forth by the discovery of the neuronal control of stress responses and transcellular chaperone signaling is: what is the identity of the intercellular stress signal(s) and how is it transduced to restore proteostasis balance? Below, we consider select examples of intercellular communication mechanisms that may be used in the regulation of cell non-autonomous proteostasis in metazoans.

Humoral control, gap junctions and nanotubes

Different specialized structures have emerged throughout evolution to provide cell-to-cell communication via direct contact, such as septal pores in fungi, plasmadesmata in plants and gap junctions in animals. While gap junctions provide portals for the direct exchange of cytoplasmic contents to efficiently propagate a signal from cell to cell, intracellular signals can also be transmitted through the extracellular space, relying on communication mechanisms such as autocrine or paracrine signaling through cytokines, ligand–receptor signaling across tight cell–cell junctions or the long-range transfer of other soluble messengers such as hormones or RNA molecules to distant target cells (Singer, 1992; Denef, 2008; Kjenseth et al., 2010). The exchange of molecules over longer distances between non-adjacent cells relies on intercellular membrane bridges that include TNTs and cytonemes (Sherer and Mothes, 2008). Moreover, recent evidence in metazoans showed that prions expressed in C. elegans can spread between tissues via autolysosomal vesicles and be released into the pseudocoelom by vesicular trafficking (Nussbaum-Krammer et al., 2013), thus providing another means for the transport of proteinacious factors between tissues.

Gap junctions have also gained attention for a phenomenon called the radiation-induced bystander effect, in which non-irradiated cells exhibit similar effects to irradiated cells as a result of signals received from nearby irradiated cells via gap junctions (Azzam et al., 2004; Azzam and Little, 2004; Mitchell et al., 2004b; Mitchell et al., 2004a). In this process, gap junctional intercellular communication may also be involved in a range of cellular stress responses including ionizing radiation and oxidative stress (Upham et al., 1998), UV radiation (Provost et al., 2003) and HS (Hamada et al., 2003). Thus, between cells in close proximity, gap junctions may have an important role in the exchange of signaling molecules for proteostasis communication. Although in C. elegans some gap junction homologues (called innexins) have been well studied, for example unc-9 and unc-7, which are required for electrical coupling of body wall muscle cells (Liu et al., 2006), the function of many C. elegans innexins remains to be established (Altun et al., 2009).

The transport of signaling molecules such as RNA across tissues and cellular boundaries has been shown in multiple organisms, including nematodes and plants, and often relies on secretion into a blood-like system for systemic transport. In C. elegans, the pericellular system, including the pseudocoelom, may provide a means for systemic cell-to-cell communication, triggered by both the nervous system and non-neuronal ‘sender tissues’. The pseudocoelom, analogous to the blood circulatory system in larger metazoans, is a fluid-filled body cavity bathing all tissues with nutrients, ions and oxygen, and may also function in intercellular signaling. Indeed, signaling via the pseudocoelom is often accomplished through hormones. For example, neuropeptides such as serotonin released from neurons into the pseudocoelom have been shown to act as signaling molecules to communicate with all tissues in an animal (Sieburth et al., 2007). Larger molecules can also be reliably transported through the pseudocoelom into other tissues, such as yolk lipoprotein particles that are synthesized in the intestine and secreted into the pseudocoelom. These particles are subsequently taken up into oocytes via RME-2 receptor-mediated endocytosis (Grant and Hirsh, 1999). Thus, the pseudocoelom could have a prominent role for signaling molecules secreted from non-neuronal tissues to other cells.

Moreover, the pseudocoelomic cavity in C. elegans is involved in distributing double-stranded (ds)RNA molecules throughout all tissues. In C. elegans, dsRNA-mediated gene interference (RNAi) systemically inhibits gene expression throughout the organism and, like in plants (Voinnet, 2001; Baulcombe, 2004), has a vital role in the immune response to foreign genetic material including viruses (Lu et al., 2005; Wilkins et al., 2005). Central for systemic distribution of dsRNA molecules in C. elegans is the transmembrane channel-forming protein SID-1, which mediates passive cellular uptake and cell-to-cell transfer (Feinberg and Hunter, 2003). Export does not require this transmembrane channel (Jose et al., 2009), suggesting that dsRNA may be endocytosed into vesicles and released into the pseudocoelom where it can be taken up via SID-1 through most tissues (Saleh et al., 2006; Jose et al., 2009). In C. elegans, as in plants and mammals, non-coding 22 nucleotide miRNAs have important gene-regulatory roles by targeting mRNAs for cleavage or translational repression (Lee et al., 1993; Saumet and Lecellier, 2006). miRNAs are involved in the regulation of development, particularly in the timing of morphogenesis (Carrington and Ambros, 2003), and are capable of regulating entire gene networks during development by modulating the expression of key regulatory transcription factors in plants (Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006). Several studies have highlighted a novel role for these molecules in intercellular communication. miRNAs can be secreted into the extracellular space, often packaged into cell-derived exosomes (Valadi et al., 2007), and circulate in human body fluid (Chim et al., 2008; Lawrie et al., 2008), which allows them to act at distant sites within an organism to regulate multiple target genes or signaling events in the recipient cells (Chen et al., 2012).

Implications for aging and disease

Aging cells and tissues accumulate misfolded and aggregated proteins as a consequence of a functional decline of the proteostasis network, leading to the development of protein-misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease. Folding challenges that arise during aging or the onset of protein-misfolding diseases likely arise from the cell-type specific regulation of protein expression that results in distinct functional proteomes within an organism. This implies that distinct cells and tissues must be prepared to detect and resolve unique folding challenges that arise during development, and in response to stress and aging (Powers et al., 2009). Likewise, many pathologies and diseases are due to limitations of specific tissues, for example dictated by the ‘selective’ expression of metastable or misfolded proteins in the tissue where they cause the pathology (Lage et al., 2008). In particular, neurons are vulnerable to protein damage as demonstrated by the remarkable prevalence of protein-misfolding diseases (Lee et al., 2006; Drummond and Wilke, 2008). Prominent examples of this class of diseases include the neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease, myopathies, diabetes mellitus and many forms of cancer. For example, in Huntington's disease, the brain tissue of affected individuals harbors amyloid aggregates that contain mutant Huntingtin proteins and other cellular proteins, including chaperones (Orr and Zoghbi, 2007).

Important breakthroughs in understanding the cellular disease processes in the context of post-mitotic cells within an organism have come through the development of invertebrate models of neurodegenerative protein-misfolding diseases. Among these studies is the use of C. elegans as a model system for the expression of polyQ repeats fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in body wall muscle cells, as seen in CAG expansion disorders such as Huntington's disease, spinocerebellar ataxias and Kennedy's disease (Morley et al., 2002). In both C. elegans and Drosophila models, the expression of polyQ repeats of different lengths in neurons, intestine and muscle recapitulates many of the molecular and cellular events associated with Huntington's disease in humans (Orr and Zoghbi, 2007), including the formation of intracellular aggregates, and has revealed a clear relationship between polyQ length, aggregation and toxicity (Satyal et al., 2000; Morley et al., 2002; Brignull et al., 2006b). The aggregation-dependent toxicity associated with polyQ proteins affects the specific cell type in which the protein is expressed in C. elegans: while polyQ protein expression in muscle tissue causes muscle cell dysfunction, expression in neuronal cells causes neural dysfunction (Satyal et al., 2000; Brignull et al., 2006a). While this disruption of proteostasis seems to cause strict cell-autonomous effects and the misfolding of other co-expressed metastable proteins (Gidalevitz et al., 2006), some features of this response in C. elegans seem to be cell non-autonomous, as disease onset is age dependent and can be modulated by the neuroendocrine ILS pathway (Morley and Morimoto, 2004). Activation of DAF-16 or HSF-1 through the ILS pathway suppresses protein aggregation and toxicity (Morley et al., 2002; Cohen et al., 2006; Ben-Zvi et al., 2009; Cohen et al., 2009), by upregulation of chaperones and other transcriptional targets of DAF-16 and HSF-1 (Balch et al., 2008). Likewise, lifespan extension does not only rely on decreased ILS signaling originating from neural tissues as endocrine signals; signals originating from mouse adipose tissue can also coordinate ageing between cells and tissues (Arantes-Oliveira et al., 2002; Blüher et al., 2003). One such potential mediator of crosstalk between tissues in mammals is associated with the hormone-like protein Klotho, as overexpression of Klotho in certain tissues is sufficient to prolong lifespan in mice (Kurosu et al., 2005). Thus, the intersection of neuroendocrine signaling pathways and cell stress-protective responses reinforces the importance of complex signaling events between cells for the organismal regulation of proteostasis.

Another line of evidence that supports the view that proteostatic disruptions in specific tissues initiate a signal to which other distant tissues can respond comes from the observation that endodermal DAF-16 can suppress certain aspects of toxicity associated with the expression of Aβ in C. elegans muscle cells (Zhang et al., 2013). Likewise, an imbalance of proteostasis through aggregation-prone proteins in non-neuronal tissue may influence proteostasis conditions in other tissues (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010). This also implies that different tissues may engage a communication system to sense proteotoxic stress occurring in distal cell types. Indeed, C. elegans seems to respond to tissue-specific imbalances of proteostasis even before the disease becomes prevalent and toxic, as demonstrated by the expression of a metastable muscle protein that induces a systemic upregulation of Hsp90 (van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013). This response occurs before age- or temperature-dependent onset of misfolding takes place, indicating that even the slightest local imbalances are detected and responded to in a cell non-autonomous manner. Thus, transcellular chaperone signaling may function to sensitize the entire organism, and the increased expression of chaperones may serve to protect the entire organism against an oncoming challenge, such as one arising through aging or other proteotoxic stress stimuli (van Oosten-Hawle et al., 2013).

Thus, although most diseases are associated with specific tissues, the existence of a transcellular chaperone response as observed in C. elegans places multiple tissues or even the entire organism in a state of ‘alert’ to initiate protective responses when necessary. Whether organisms other than C. elegans employ transcellular chaperone signaling to communicate local proteotoxic stress remains to be established. Larger metazoans may communicate such stress events by a combination of direct signaling between cells and tissues and via lymphatic and circulatory systems to achieve events at a distance to coordinate cellular and organismal proteostasis.

Concluding remarks

The complexity of the regulation of proteostasis in metazoans provides multiple control points to ensure the robustness of a process that is crucial for viability of the entire organism. Clearly, cellular behavior in an organism must have evolved to benefit the whole animal, rather than individual cells. Consistent with this notion, proteostasis maintenance in metazoans relies on multiple modes of cell non-autonomous mechanisms, including the integration of environmental signals through neuronal pathways and neuroendocrine signaling, as well as the emerging concept of transcellular chaperone signaling that integrates cell-specific and organismal stress responses independent of neural control. Transcellular chaperone signaling may rely on many different modes of intercellular communication that are protective to organismal lifespan on the one hand, and become pathological when mismanaged during disease on the other. Understanding how these concepts extend to larger metazoans together with the identification and comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms will be instrumental for the development of novel approaches for the treatment of protein-misfolding diseases and other diseases associated with aging.

FOOTNOTES

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

P.v.O.-H. was supported by an Erwin-Schroedinger postdoctoral fellowship by the Austrian Science Fund (FWFJ2895) and a Chicago Center for Systems Biology Postdoctoral Fellowship supported by NIGMS P50 grant (P50-GM081192) and the Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community trust. R.I.M. is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS, NIA, NINDS), the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium and the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Abravaya K., Phillips B., Morimoto R. I. (1991). Attenuation of the heat shock response in HeLa cells is mediated by the release of bound heat shock transcription factor and is modulated by changes in growth and in heat shock temperatures. Genes Dev. 5, 2117-2127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abravaya K., Myers M. P., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. (1992). The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev. 6, 1153-1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerfelt M., Morimoto R. I., Sistonen L. (2010). Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 545-555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcedo J., Kenyon C. (2004). Regulation of C. elegans longevity by specific gustatory and olfactory neurons. Neuron 41, 45-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A., Bharadwaj S., O'Carroll R., Ovsenek N. (1998). HSP90 interacts with and regulates the activity of heat shock factor 1 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4949-4960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altun Z. F., Chen B., Wang Z. W., Hall D. H. (2009). High resolution map of Caenorhabditis elegans gap junction proteins. Dev. Dyn. 238, 1936-1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anckar J., Sistonen L. (2007). SUMO: getting it on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1409-1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anfinsen C. B. (1973). Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181, 223-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantes-Oliveira N., Apfeld J., Dillin A., Kenyon C. (2002). Regulation of life-span by germ-line stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 295, 502-505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam E. I., Little J. B. (2004). The radiation-induced bystander effect: evidence and significance. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 23, 61-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam E. I., de Toledo S. M., Little J. B. (2004). Stress signaling from irradiated to non-irradiated cells. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 4, 53-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch W. E., Morimoto R. I., Dillin A., Kelly J. W. (2008). Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319, 916-919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler R., Dahl G., Voellmy R. (1993). Activation of human heat shock genes is accompanied by oligomerization, modification, and rapid translocation of heat shock transcription factor HSF1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 2486-2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulcombe D. (2004). RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431, 356-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R., Schaffitzel E., Hertweck M. (2006). Endocrine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans controls stress response and longevity. J. Endocrinol. 190, 191-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi A., Miller E. A., Morimoto R. I. (2009). Collapse of proteostasis represents an early molecular event in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14914-14919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüher M., Kahn B. B., Kahn C. R. (2003). Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science 299, 572-574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignull H. R., Morley J. F., Garcia S. M., Morimoto R. I. (2006a). Modeling polyglutamine pathogenesis in C. elegans. Methods Enzymol. 412, 256-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignull H. R., Moore F. E., Tang S. J., Morimoto R. I. (2006b). Polyglutamine proteins at the pathogenic threshold display neuron-specific aggregation in a pan-neuronal Caenorhabditis elegans model. J. Neurosci. 26, 7597-7606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington J. C., Ambros V. (2003). Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science 301, 336-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Schumacher M. A., Tominaga M., Rosen T. A., Levine J. D., Julius D. (1997). The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389, 816-824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liang H., Zhang J., Zen K., Zhang C. Y. (2012). Secreted microRNAs: a new form of intercellular communication. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 125-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang W. C., Ching T. T., Lee H. C., Mousigian C., Hsu A. L. (2012). HSF-1 regulators DDL-1/2 link insulin-like signaling to heat-shock responses and modulation of longevity. Cell 148, 322-334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chim S. S., Shing T. K., Hung E. C., Leung T. Y., Lau T. K., Chiu R. W., Lo Y. M. (2008). Detection and characterization of placental microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 54, 482-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D. E. (2003). TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature 426, 517-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Bieschke J., Perciavalle R. M., Kelly J. W., Dillin A. (2006). Opposing activities protect against age-onset proteotoxicity. Science 313, 1604-1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Paulsson J. F., Blinder P., Burstyn-Cohen T., Du D., Estepa G., Adame A., Pham H. M., Holzenberger M., Kelly J. W., et al. (2009). Reduced IGF-1 signaling delays age-associated proteotoxicity in mice. Cell 139, 1157-1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypser J., Johnson T. E. (2001). Hormesis extends the correlation between stress resistance and life span in long-lived mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 20, 295-296, discussion 319-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono M., Maricq A. V. (2005). Neuronal substrates of complex behaviors in C. elegans. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28, 451-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demontis F., Perrimon N. (2010). FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 143, 813-825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef C. (2008). Paracrinicity: the story of 30 years of cellular pituitary crosstalk. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 1-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond D. A., Wilke C. O. (2008). Mistranslation-induced protein misfolding as a dominant constraint on coding-sequence evolution. Cell 134, 341-352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux J., Wolff S., Dillin A. (2011). The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell 144, 79-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. J., Minton A. P. (2006). Protein aggregation in crowded environments. Biol. Chem. 387, 485-497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E. H., Hunter C. P. (2003). Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 301, 1545-1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallio M., Ofstad T. A., Macpherson L. J., Wang J. W., Zuker C. S. (2011). The coding of temperature in the Drosophila brain. Cell 144, 614-624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S. M., Casanueva M. O., Silva M. C., Amaral M. D., Morimoto R. I. (2007). Neuronal signaling modulates protein homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans post-synaptic muscle cells. Genes Dev. 21, 3006-3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidalevitz T., Ben-Zvi A., Ho K. H., Brignull H. R., Morimoto R. I. (2006). Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science 311, 1471-1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B., Hirsh D. (1999). Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4311-4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettouche T., Boellmann F., Lane W. S., Voellmy R. (2005). Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem. 6, 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada N., Kodama S., Suzuki K., Watanabe M. (2003). Gap junctional intercellular communication and cellular response to heat stress. Carcinogenesis 24, 1723-1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes C. M., Ron D. (2010). The mitochondrial UPR – protecting organelle protein homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 123, 3849-3855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietakangas V., Ahlskog J. K., Jakobsson A. M., Hellesuo M., Sahlberg N. M., Holmberg C. I., Mikhailov A., Palvimo J. J., Pirkkala L., Sistonen L. (2003). Phosphorylation of serine 303 is a prerequisite for the stress-inducible SUMO modification of heat shock factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2953-2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg C. I., Hietakangas V., Mikhailov A., Rantanen J. O., Kallio M., Meinander A., Hellman J., Morrice N., MacKintosh C., Morimoto R. I., et al. (2001). Phosphorylation of serine 230 promotes inducible transcriptional activity of heat shock factor 1. EMBO J. 20, 3800-3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu A. L., Murphy C. T., Kenyon C. (2003). Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science 300, 1142-1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo D. S., Gershman B., Tu M. P., Palmer M., Tatar M. (2004). Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature 429, 562-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada H., Ito H., Satterlee J., Sengupta P., Matsumoto K., Mori I. (2006). Identification of guanylyl cyclases that function in thermosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 172, 2239-2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades M. W., Bartel D. P., Bartel B. (2006). MicroRNAS and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 19-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose A. M., Smith J. J., Hunter C. P. (2009). Export of RNA silencing from C. elegans tissues does not require the RNA channel SID-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2283-2288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjenseth A., Fykerud T., Rivedal E., Leithe E. (2010). Regulation of gap junction intercellular communication by the ubiquitin system. Cell. Signal. 22, 1267-1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline M. P., Morimoto R. I. (1997). Repression of the heat shock factor 1 transcriptional activation domain is modulated by constitutive phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2107-2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu H., Yamamoto M., Clark J. D., Pastor J. V., Nandi A., Gurnani P., McGuinness O. P., Chikuda H., Yamaguchi M., Kawaguchi H., et al. (2005). Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309, 1829-1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage K., Hansen N. T., Karlberg E. O., Eklund A. C., Roque F. S., Donahoe P. K., Szallasi Z., Jensen T. S., Brunak S. (2008). A large-scale analysis of tissue-specific pathology and gene expression of human disease genes and complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20870-20875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie C. H., Gal S., Dunlop H. M., Pushkaran B., Liggins A. P., Pulford K., Banham A. H., Pezzella F., Boultwood J., Wainscoat J. S., et al. (2008). Detection of elevated levels of tumour-associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 141, 672-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Kenyon C. (2009). Regulation of the longevity response to temperature by thermosensory neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 19, 715-722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843-854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. W., Beebe K., Nangle L. A., Jang J., Longo-Guess C. M., Cook S. A., Davisson M. T., Sundberg J. P., Schimmel P., Ackerman S. L. (2006). Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature 443, 50-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. L., Kelly J. W. (2011). Chemical and biological approaches for adapting proteostasis to ameliorate protein misfolding and aggregation diseases: progress and prognosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Chang A. (2008). Heat shock response relieves ER stress. EMBO J. 27, 1049-1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Chen B., Gaier E., Joshi J., Wang Z. W. (2006). Low conductance gap junctions mediate specific electrical coupling in body-wall muscle cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7881-7889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Maduro M., Li F., Li H. W., Broitman-Maduro G., Li W. X., Ding S. W. (2005). Animal virus replication and RNAi-mediated antiviral silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 436, 1040-1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen P. D., Aprison E. Z., Winter P. B., Amaral L. A., Morimoto R. I., Ruvinsky I. (2012). Macro-level modeling of the response of C. elegans reproduction to chronic heat stress. PLOS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. A., Randers-Pehrson G., Brenner D. J., Hall E. J. (2004a). The bystander response in C3H 10T1/2 cells: the influence of cell-to-cell contact. Radiat. Res. 161, 397-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. A., Marino S. A., Brenner D. J., Hall E. J. (2004b). Bystander effect and adaptive response in C3H 10T(1/2) cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 80, 465-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I. (1999). Genetics of chemotaxis and thermotaxis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33, 399-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I., Sasakura H., Kuhara A. (2007). Worm thermotaxis: a model system for analyzing thermosensation and neural plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 712-719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J. F., Morimoto R. I. (2004). Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 657-664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J. F., Brignull H. R., Weyers J. J., Morimoto R. I. (2002). The threshold for polyglutamine-expansion protein aggregation and cellular toxicity is dynamic and influenced by aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10417-10422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund A. M., Pellegrino M. W., Fiorese C. J., Baker B. M., Haynes C. M. (2012). Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science 337, 587-590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum-Krammer C. I., Park K. W., Li L., Melki R., Morimoto R. I. (2013). Spreading of a prion domain from cell-to-cell by vesicular transport in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y. (2007). Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 575-621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers E. T., Morimoto R. I., Dillin A., Kelly J. W., Balch W. E. (2009). Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 959-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V., Morimoto R. I. (2009). Integrating the stress response: lessons for neurodegenerative diseases from C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 52-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V., Morimoto R. I. (2011). Neuronal circuitry regulates the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to misfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14204-14209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V., Cornelius T., Morimoto R. I. (2008). Regulation of the cellular heat shock response in Caenorhabditis elegans by thermosensory neurons. Science 320, 811-814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost N., Moreau M., Leturque A., Nizard C. (2003). Ultraviolet A radiation transiently disrupts gap junctional communication in human keratinocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 284, C51-C59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W., Huang X., Neumann-Haefelin E., Schulze E., Baumeister R. (2012). Cell-nonautonomous signaling of FOXO/DAF-16 to the stem cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D., Walter P. (2007). Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M. C., van Rij R. P., Hekele A., Gillis A., Foley E., O'Farrell P. H., Andino R. (2006). The endocytic pathway mediates cell entry of dsRNA to induce RNAi silencing. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 793-802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson A. V., Carr C. E., Ruvkun G. (2007). Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C. elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes Dev. 21, 2976-2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarge K. D., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. (1993). Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 1392-1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyal S. H., Schmidt E., Kitagawa K., Sondheimer N., Lindquist S., Kramer J. M., Morimoto R. I. (2000). Polyglutamine aggregates alter protein folding homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5750-5755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saumet A., Lecellier C. H. (2006). Anti-viral RNA silencing: do we look like plants? Retrovirology 3, 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder M., Kaufman R. J. (2005). The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 739-789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J. A. (1998). Thinking about bacterial populations as multicellular organisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52, 81-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer N. M., Mothes W. (2008). Cytonemes and tunneling nanotubules in cell-cell communication and viral pathogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 414-420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Mosser D. D., Morimoto R. I. (1998). Molecular chaperones as HSF1-specific transcriptional repressors. Genes Dev. 12, 654-666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D., Madison J. M., Kaplan J. M. (2007). PKC-1 regulates secretion of neuropeptides. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 49-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S. J. (1992). Intercellular communication and cell-cell adhesion. Science 255, 1671-1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer K. L., Singh V., Macosko E., Steele S. E., Bargmann C. I., Aballay A. (2008). Innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans is regulated by neurons expressing NPR-1/GPCR. Science 322, 460-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugi T., Nishida Y., Mori I. (2011). Regulation of behavioral plasticity by systemic temperature signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 984-992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Singh V., Kajino-Sakamoto R., Aballay A. (2011). Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science 332, 729-732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Liu Y., Aballay A. (2012). Organismal regulation of XBP-1-mediated unfolded protein response during development and immune activation. EMBO Rep. 13, 855-860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. C., Dillin A. (2013). XBP-1 is a cell-nonautonomous regulator of stress resistance and longevity. Cell 153, 1435-1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upham B. L., Deocampo N. D., Wurl B., Trosko J. E. (1998). Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication by perfluorinated fatty acids is dependent on the chain length of the fluorinated tail. Int. J. Cancer 78, 491-495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadi H., Ekström K., Bossios A., Sjöstrand M., Lee J. J., Lötvall J. O. (2007). Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 654-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oosten-Hawle P., Porter R. S., Morimoto R. I. (2013). Regulation of organismal proteostasis by transcellular chaperone signaling. Cell 153, 1366-1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T., Droogmans G., Wissenbach U., Janssens A., Flockerzi V., Nilius B. (2004). The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature 430, 748-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O. (2001). RNA silencing as a plant immune system against viruses. Trends Genet. 17, 449-459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerheide S. D., Anckar J., Stevens S. M., Jr, Sistonen L., Morimoto R. I. (2009). Stress-inducible regulation of heat shock factor 1 by the deacetylase SIRT1. Science 323, 1063-1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins C., Dishongh R., Moore S. C., Whitt M. A., Chow M., Machaca K. (2005). RNA interference is an antiviral defence mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 436, 1044-1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R., Shawn Xu X. Z. (2011). Studying TRP channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. In TRP Channels (ed. Zhu M. X.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R., Zhang B., Dong Y., Gong J., Xu T., Liu J., Xu X. Z. (2013). A genetic program promotes C. elegans longevity at cold temperatures via a thermosensitive TRP channel. Cell 152, 806-817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Judy M., Lee S. J., Kenyon C. (2013). Direct and indirect gene regulation by a life-extending FOXO protein in C. elegans: roles for GATA factors and lipid gene regulators. Cell Metab. 17, 85-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Guo Y., Guettouche T., Smith D. F., Voellmy R. (1998). Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell 94, 471-480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]