Abstract

Hispanic men who have sex with men (MSM) experience a number of health disparities including high rates of HIV infection from high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. Although some research is available to document the relationships of these health disparities in the literature, few studies have explored the intersection of these disparities and the factors that influence them. The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences that Hispanic MSM residing in South Florida have with high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. Focus groups were conducted and analyzed using grounded theory methodology until data saturation was reached (n = 20). Two core categories with subcategories emerged from the data: The Roots of Risk (Los raices del riesgo) and The Tangled Branches (Las Ramas Enredadas). The results of the study provided some important clinical implications as well as directions for future research with Hispanic MSM.

Keywords: Gay men, Hispanics, Qualitative research, Sexual risk, Substance abuse, Intimate Partner Violence

Hispanic men who have sex with men (MSM) are a vulnerable population with a number of health disparities (De Santis, 2010). These health disparities include HIV infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010); substance abuse (Cochran, Mays, Alegria, Ortega & Takeuchi, 2007); and violence and abuse (Feldman, Diaz, Ream & El-Bassel, 2007). Studies have documented the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence among the general population of Hispanics (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2004; Gonzalez-Guarda, Peragallo, Urrutia & Vasquez, 2008). However, no studies have explored the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse and violence among Hispanic MSM. In addition, interventions to address these health risk factors in tandem that are targeted to Hispanic MSM have not been developed. Given this identified gap in the research literature, Project VIDA (Violence, Intimate Relationships and Drugs among Latinos) was designed as a mixed-method pilot study with the overarching aim of examining the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence within a cultural context among Hispanic heterosexual men as well as Hispanic MSM. This article reports on the focus groups conducted with Spanish-speaking Hispanic MSM.

Health Risk Factors among Hispanic MSM

Sexual Risk

A number of studies have documented that Hispanic MSM engage in high risk sexual behaviors. Participation in high risk sexual behaviors places Hispanic MSM at risk for sexually transmitted infections that includes HIV infection (CDC, 2010). A study of 135 foreign-born Hispanic MSM conducted by De Santis (in press), reported that 94.1% (n = 127) engaged in anal intercourse and that 40% (n = 54) had unprotected anal intercourse (UAI). Nakamura and Zea (2010) enrolled 226 Hispanic gay and bisexual men in a study that examined homonegativity and sexual risk behaviors. The researchers reported that 32% (n = 73) of the participants reported unprotected insertive anal intercourse in the past 30 days with a mean number of episodes of UAI was 6 (range = 1-30). Unprotected receptive anal intercourse in the previous 30 days was reported by 25% (n = 56) of the participants, with the same mean number of episodes of 6 (range = 1-30).

A study by Bianchi and colleagues (2006) surveyed 239 Hispanic MSM with HIV infection. The sample consisted of 75 Brazilians, 61 Puerto Ricans, and 103 South Americans. The majority of the participants reported UAI with their most recent sexual partner: Brazilians (66%), Puerto Ricans (52%), and South Americans (62%). The researchers concluded that the high rates of UAI are consistent with previous research and contribute to the prevalence of HIV infection among Hispanic MSM.

Substance Abuse

Much like the general population of MSM, Hispanic MSM engage in substance abuse. Compared to what is known about substance abuse among the MSM community, research on substance abuse by Hispanic MSM is limited. In a qualitative study by Bauermeister (2007) conducted in San Francisco, participants reported that substance abuse by Hispanic MSM was used to cope with sexual identity, to integrate into mainstream gay culture, and to reduce sexual inhibitions.

In a study of 300 stimulant-using Hispanic MSM conducted in San Francisco, Diaz and colleagues (2005) reported that 51% (n = 153) reported methamphetamine use, 44% (n = 133) used cocaine, and 5% (n = 14) used “crack” cocaine. Reasons for stimulant use included sexual enhancement and social connectedness.

Intimate Partner Violence

Studies have been conducted that document intimate partner violence (IPV) among Hispanic MSM. A large multisite study of 913 Hispanic gay and bisexual men reported that 52% reported a lifetime prevalence of IPV: 45% reported psychological violence, 33% reported physical violence, and 10% reported sexual violence (Feldman et al., 2007).

In a study of 199 Puerto Rican gay male couples, 40% reported emotional violence, 24% physical violence, and 14% sexual violence. Despite these rates, only 24% perceived that they were involved in a violent relationship. In terms of violence experienced during childhood, 49% reported emotional violence, 42% physical violence, and 14% sexual violence. A relationship between childhood violence and adult violence was noted in terms of emotional violence (X2 = 9.150, df = 1, p < .003), physical violence (X2 = 5.077, df = 1, p < .025), sexual violence (X2 = 5.682, df = 1, p < .022), and sexual violence (X2 = 7.412, df = 1, p < .011) (Toro-Alfonso & Rodriguez-Madera, 2004).

Relationship of Sexual Risk, Substance Abuse, and Violence

Research studies that document the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM have not been conducted. Studies are available, however, that document the relationship of sexual risk and substance abuse and sexual risk and violence as two independent relationships. The relationship of violence and substance abuse among Hispanic MSM has not been conducted.

In terms of sexual risk and substance abuse, a study of 566 Hispanic MSM in South Florida noted that MSM who used substances were more likely to participate in UAI (OR = 2.53, p < .001). In addition, substance users were more likely to be infected with HIV when compared to non-substance users (OR = 2.40, p < .001) (Fernandez, Jacobs, Warren, Sanchez & Bowen, 2009). A study of 270 Hispanic MSM from New York City, Los Angeles, and Miami noted that substance use by a sexual partner (B = 0.62, OR = 1.82, p < .05) and discussions regarding condom usage (B = −1.15, OR = 0.32, p < .001) were predictors of UAI (Wilson, Diaz, Yoshikawa & Shrout, 2009).

The relationship of sexual risk and intimate partner violence (IPV) was explored by using path analysis to model the situational factors associated with HIV risk and IPV. The study surveyed 912 Hispanic MSM from New York, Miami, and Los Angeles. A history of psychological abuse (B = 0.646, p < .05) and sexual abuse (B = 1.233, p < .05) were directly related to UAI, while physical abuse was indirectly associated with UAI (B = 0.358, p < .05) (Feldman, Ream, Diaz & El-Bassel, 2007).

No studies have been conducted that examined the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM. Based on this identified gap in the research literature, this study was designed to describe the relationship of risky sexual behavior, substance abuse, and violence within the cultural context of Hispanic MSM.

Method

Design

This study is part of a larger study, Project VIDA, that utilized a mixed-method approach to understand risky behaviors and mental health among adult Hispanic heterosexual men and MSM. The scarcity of research on sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence led to the selection of grounded theory as the research method to guide the qualitative component of this study. Grounded theory is used to generate a theory that explains an action, process, or to describe the interaction of phenomena (Creswell, 2009; Glaser &Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Three focus groups were conducted with Spanish speaking Hispanic MSM (N = 20) to gather their perceptions and concerns regarding how risky sexual behaviors, substance abuse and violence affected the Hispanic MSM community. Focus groups allow researchers to generate data that is grounded on individuals' perceptions regarding phenomena of interest and allows participants to interact, agree, disagree and come to a consensus on this phenomenon (Morgan, 1997). Although the research team also conducted focus groups with heterosexual Hispanic males, these were analyzed separately and are reported elsewhere (Gonzalez-Guarda, Ortega, Vasquez & De Santis, 2010).

Sample and Setting

Eligibility criteria for this study included self-identifying as being a Hispanic or Latino male, between the ages of 18 and 55, living in South Florida, and bisexual or homosexual. Tourists and individuals planning to relocate within the following year were excluded from the study. Community-based recruitment methods were used to inform candidates about the study. Study staff handed out study flyers and approached candidates in person at nightclubs, community centers and clinics, shopping centers and community events in areas of South Florida where there was a high concentration of Hispanic MSM. Snowball sampling techniques were also used (Creswell, 2009). Data collection was carried out in a private study office located in downtown Miami.

Procedures

IRB approval was obtained prior to beginning study related activities. All focus group participants had participated in the first phase of the study, which involved a structured quantitative assessment. Participants were asked if they identified as being heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual. Individuals who identified as being bisexual, homosexual and/or transgendered were called by the research team and invited to participate in the focus groups. Those who agreed to participate were grouped according to language preference (i.e., English or Spanish). Because the majority of participants preferred to speak in Spanish, all focus groups were conducted in Spanish. Prior to beginning the discussion, participants were invited to eat a light dinner served on site. During the meal, participants had time to get to know one another and establish rapport with the research staff. The facilitator and co-fascilitator also described the study procedures, established ground rules for the discussion, answered questions and acquired informed consent. Focus group discussions were guided by a semi-structured interview that included open-ended questions and probes. This guide is described in more detail elsewhere (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011). Each focus group discussion lasted approximately 1.5 hours, were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated.

Analysis

Investigators used grounded theory to code the focus group transcripts (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). First, investigators read through the transcripts without coding. Then, they identified categories that were grounded in the data (open coding). Constant comparisons were used to compare existing codes with new codes that emerged from the data and to allow from the integration of accumulated knowledge (Swanson & Chenitz, 1982; Glaser, 1992). Relationships between these categories were also coded (axial coding). Codes that clustered together were assigned to core categories, and used to generate an abstract depiction of the phenomena (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Data was evaluated for recurring patterns of like and unlike meanings. Saturation was reached by the third focus group.

To establish rigor, two methods were used: clarifying researcher bias and peer review/debriefing (Creswell, 2009). Because the first three authors have extensive research experience with Hispanic men that could influence data analysis, the fourth author who lacks research experience with this population verified the identified categories by comparing the categories to the data. Peer review/debriefing was the second method used to establish rigor. Peer review/debriefing was accomplished by researchers who were not affiliated with the research center where the data were collected to review and confirm the findings. Comments made by the peer reviewers were incorporated into the results.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Twenty participants completed one of the four focus groups. Participants were between 26 and 54 years of age (M = 43.60, SD = 8.61). All of the participants were foreign-born, a large proportion of whom reported being born in Cuba (n = 9, 45%). The remaining participants reported being born in Puerto Rico, Honduras, Nicaragua, or Colombia (n = 2, 10% for each country), or Costa Rica, Peru and Chile (n =1, 5% for each country). Using the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale [ BAS] (Marin & Gamba, 1996), it was determined that the sample was more acculturated to the Hispanic culture (M = 3.63, SD = .31) than to the American culture (M = 2.60, SD = .83), although 45% (n = 9) were both highly Hispanic and highly American. The majority of the participants who provided information about their income (n = 9, 45%) reported an income of less than $500 a month. About half of the participants completed at least 12 years of education (M = 12.40, SD = 4.28).

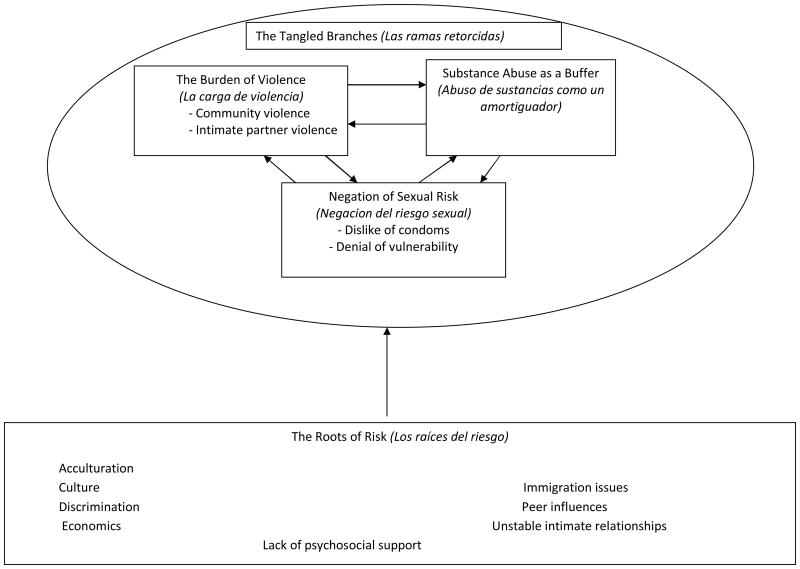

Participants provided rich descriptions of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence. These descriptions were used to illustrate the process by which sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence occurs among Hispanic MSM (see Figure 1). Selected quotes from the focus group participants are used to illustrate the categories.

Figure 1. The Tangled Branches.

Sexual risk, substance and intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM

The Roots of Risk (Los raices del riesgo)

Participants reported that numerous factors provided a foundation for sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM. Participants easily identified the factors that were common in this population that provided a foundation for sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence. These factors were categorized as “The Roots of Risk” because participants reported that these roots “strengthened each other and were difficult to remove.” One root in particular, acculturation was reportedly a significant challenge for participants. Upon arrival to the U.S., participants reported the need to acculturate in order to integrate into the predominate culture. This need to acculturate, however, often resulted in stressors that were often resulted in substance abuse, high risk sexual behavior and sometimes violence:

While we stay in our group, the less we integrate into the system…So, then what happens to the people? They get hit hard because on top of (everything else) that gets added up, that dream becomes a nightmare. In that lifestyle you get to know alcohol, drugs, and sex and violence. Necessity leads us them to it.

Hispanic culture was also viewed one of the roots of risk.. The Hispanic cultural value of machismo, which glorifies sexual prowessness and hypersexuality, was one of the cultural attributes most widely discussed as a major source of risk for Hispanic MSM. A man who prescribes to the machista mentality often engages in substance abuse, high risk sex, and may become violent in his relationships. As one participant described:

Latinos are more caliente (sexually-charged) than Anglos…Condoms are used only when somebody demands it; (therefore) condoms are almost never used. People don't like to use condoms because it is like showering with an umbrella. Everything like sex, drugs, and violence depends on your cultural level, your background, your relationships, if you carry it out from a risk point of view or not.

Discrimination is a factor that had a profound impact on the participants. Participants experienced multiple forms of external and internal forms of discrimination relating to their intersecting identities. They described being discriminated for both their ethnic identify and sexual orientation. As one participant described:

Ethnic and minority discrimination because generally they don't treat me like that, moreover, treating me so differently sometimes I fell also discriminated (against) because in reality I am gay and I am Latino, and I feel they are treating me in a way different compared to someone that is next to me.

Participants also described discrimination to be external, perpetrated by non-Hispanics, and internal, perpetrated by certain Hispanic sub-groups with higher status in the community. As described by one participant:

I've realized that the worst enemy is us. Americans have sincerely treated me like one of them. I believe that discrimination is seen much more among Hispanics. Cubans discriminate (against other) Latins. Moreover, there exists a bit of discrimination among Cubans… especially the ones that came before and the ones that came recently. I see it more often than…between Anglos and African-Americans with Latinos.

The economic situation of many participants promoted high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence. When it was not possible to procure employment, some participants reported engaging in commercial sex work for money or drugs. Economic pressures also increased substance use, and for those in relationships, tension related to economics often resulted in violence:

If you have a stable life, everything depends on this. Look, economics is the key. If you have stable economics and you are situated, you don't have reasons to do anything risky. People prostitute themselves for economic reasons. Economic desperation leads to violence…and I think that is a serious factor that can lead to drugs, alcohol, and prostitution.

A number of participants reported that immigration issues produced stress that promoted high risk sex, substance use, and violence. Immigration problems resulted in some participants engaging in prostitution, abusing substances, and experiencing violence:

(Because of immigration) not everybody has all the same opportunities. The Cuban has different opportunities than the Mexican, everyone is different. (Because of this) there are people that prostitute themselves out of necessity. I started to do it out of necessity. Now you have money. It is not that. You want to go away, but you can't. You want to break the bad circle. That is because a person who has immigration problems can't get help and that is what we are talking about. You asked me what problems do we have here because of that? Problems 1, 2, and 3 (high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence).

Participants reported that peer influences contributed to high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence. Numerous examples were provided by participants that illustrated how participants were influenced by their peers to enage in high risk sex and substance abuse. In addition, participants noted that peers often encouraged them to remain in violent relationships.

What I am saying is that everything (high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence) depends on the circle you are in…You simply have to be careful with the things that can do you harm. It's tough. It's hard, but you have to want it for yourself, not for him or the other guy. And for somebody who is trying to get out of these things (high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence), they recommend that you don't hang out with those people…

The inability to maintain stable intimate relationships was also perceived as a major risk factor to risky sexual behaviors, substance abuse and violence. Participants described the difficulty of maintaining these stable intimate relationships for various reasons, including society's acceptance of infidelity as a norm and the difficulty of maintaining relationships with individuals with different cultural values. As one participant described:

Why do so many couples here in Florida need to have a lover outside of the relationship?…It is a serious problem that is socially enjoyed…How am I going to risk having sex with you if I do not know where you were last night?

The final root of risk reported by participants is a lack of psychosocial support. Despite having support from peers that often resulted in negative behaviors, participants reported that psychosocial support was not available to mediate the effects of high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence:

About six months later my aunt realized I was gay and threw me out onto the street. ‘We don't want you here. We don't accept gay people in our house.’ I had to leave my studies and that's where the drugs come in… and many times I had to sleep with people for money. They paid my rent, and I had to do it for money, and for money I got HIV.

The Tangled Branches (Las Ramas Enredadas)

According to the participants, The Roots of Risk provide a foundation that leads to the second category that emerged from the data. This category was termed The Tangled Branches (Las Ramas Enredadas) and contains the subcategories of Negation of Sexual Risk, Substance Abuse as a Buffer, and the Burden of Violence. Participants provided information on the relationship of the subcategories.

Negation of Sexual Risk (Negacion del Riesgo Sexual)

Participants were vocal in noting that Hispanic MSM engage in high risk sexual behaviors mostly because of the denial or negation of sexual risk. A lack of knowledge of sexual risk that could result in HIV infection was not reported by the participants. In fact, participants believed that is was a general dislike for the use of condoms and an unwillingness to accept that they are vulnerable to HIV infection that interfered with safer sexual behaviors. One participant said:

Hispanics just don't like to use condoms because with all the information, with everything we know about AIDS and the (other) venereal diseases that exist, people should use condoms. You know that it (HIV) is a reality, and that it exists. People don't want to know that it exists, or simply they want to cover it up with a finger.

Substance Abuse as a Buffer (Abuso de Sustancias Como un Amortiguador)

Hispanic MSM engage in substance abuse mainly as a means to buffer negative events or emotions, according to the participants. Substance abuse was used as a buffer against loneliness, separation from family, a lack of support, etc.

I haven't been living here long, but I've realized that here I no longer have friends. I no longer have close family. Alcohol is an escape from problems instead of attempting to solve them. Sometimes drugs fill the person with a need. They seek refuge many times in drugs and alcohol…that gives a sense of security and that is what makes me feel comfortable.

The Burden of Violence (La Carga de Violencia)

Focus group participants voiced concern regarding the impact that violence has on the Hispanic MSM community. In addition to the report of external sources of violence directed at Hispanic MSM related to sexual orientation, participants were most concerned about the impact of violence that occurred in intimate relationships:

…There is community violence, but also hidden community violence: like your partner threatening you all the time and he manipulates your mind. The worst period of abuse is when they mistreat you psychologically. It is much worse than hitting, and the first thing they achieve is to get you to be afraid. They have things hidden inside and they release them at home.

The Relationship of Sexual Risk, Substance Abuse, and Violence

The study participants viewed sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence as inter-related health issues that impacted the Hispanic MSM community. Participants viewed these health issues as tangled branches that were supported or rooted in cultural, psychosocial, and social aspects affecting Hispanic MSM. In summarizing the relationship of sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence, one participant reported:

…With a lack of care, affection, vision, a home, the lack of everything, all these things (sex, drugs, and violence) are totally related…We have to attack the causes at its roots. If you don't cut it out at the roots, the cancer grows. Eliminate the cancer at the root, not the branches because they come out again.

Participants were very interested in discussing with the researchers methods that could be used to address high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM. The method that participants believed would be most beneficial to help Hispanic MSM decrease high risk sexual behaviors, substance abuse, and violence was a support group:

If I see a small group, it could save me from this type of things (high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence). Gays are discriminated and are very fearful people. That is why we need growth groups where we can talk to people, where people can understand what is going on with themselves…, for people to be able to share, understand each other, and help each other…The fundamental thing is to build groups of personal growth so that people can attend.

Discussion

The results of the study on sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM are important because no studies to date have examined the relationship of these factors among this population. The first category (The Roots of Risk/Los Raices del Riesgo) notes the important role that cultural, psychosocial, and social factors play in influencing high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence among Hispanic MSM.

This study's results suggest that acculturation to mainstream U.S. culture could be both a risk and protective factor for the acquisition of HIV infection. The positive association between acculturation to the U.S. culture and risk for HIV infection is supported by previous research conducted with Hispanic MSM which noted that more acculturated Hispanic men participated in more high risk sexual behaviors under the influence of substances, while less acculturated Hispanic men were less likely to participate in high risk sexual behaviors under the influence of substances (Nakamura & Zea, 2010). Another study by Poppen and colleagues (2004) found that HIV-infected Hispanic MSM that were more acculturated reported more sexual partners and were more likely to participate in unprotected receptive anal intercourse, a high risk sexual behavior. Conversely, participants also reported that a lack of acculturation could also be a risk factor for HIV infection. The participants believed that the majority of Hispanic MSM did not like to use condoms during anal intercourse, and that less acculturated men mainly had sexual relations with only other Hispanic men who also did not like to use condoms. One possible explanation for the contradictory nature of these findings may be the demographic characteristics of the study site. Because Spanish is a predominate language in South Florida and Hispanic comprise a large proportion of the population, Hispanic MSM are not required to acculturate in order to form friendships, find sexual partners, etc. This fact could therefore contribute to participants acculturating at a different rate or manner than Hispanics in other geographical areas in the U.S.. More research is needed to understand the complex nature of acculturation and health risk behavior among Hispanic MSM.

Participants in this study reported that the Hispanic cultural factor of machismo influenced sexual behaviors, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. The influence of machismo on risk behaviors is well-documented among heterosexual Hispanic men (Falicov, 2010; Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011). Some literature is available that documents the influence of machismo on the sexual behaviors of young Hispanic MSM (Meyer &Champion, 2008) and gay and bisexual Hispanic MSM (Carballo-Dieguez et al., 2004). This study adds some unique information to the knowledge base in that it qualitatively links machismo with not only high risk sexual behaviors, but substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. Quantitative research is needed to explore the influence of Hispanic cultural factors such as machismo on high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM.

Participants in this study reported that internal and external sources of discrimination resulted in stress that was mitigated by high risk sexual behaviors and substance abuse, and sometimes intimate partner violence. Discrimination and racism toward Hispanic MSM has been noted to result in anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, &Marin, 2001). The influence of discrimination on high risk sexual behaviors of Hispanic MSM has been noted (Diaz, Ayala & Bein, 2004), but the relationship of discrimination, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM has not been investigated. More detailed information regarding the nature and direction of the relationships amongdiscrimination, high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner is needed.

Economic factors contributed to high risk sex, substance abuse, and violence among the study's participants. Economic factors may be impacted by difficulty in procuring employment because of immigration issues, language barriers, etc. The economic factors contributed to stress, according to the participants, resulting in high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. No research studies could be located that noted the influence of economic factors on substance abuse and intimate partner violence, but a few studies have explored the influence of economic factors on high risk sexual behaviors among Hispanic MSM. These studies have documented that some Hispanic MSM have engaged in commercial sex work in order to secure money and housing (Diaz et al., 2004; Galvan, Ortiz, Martinez, & Bing, 2010). Not only are these men at risk for HIV infection because of multiple sexual partners, but because the men were engaging in anal sex without condoms with their sexual partners (Galvan et al., 2010). Clearly more research is needed to understand the impact of economic factors on high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM.

The findings on the role of that unstable intimate relationships and access to psychosocial support plays in influencing sexual risk behaviors, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence provide some new information. Interestingly, the Hispanic MSM participants were more likely to discuss the importance of maintaining an intimate relationship than heterosexual Hispanic MSM (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2011). As described by the participants, it was difficult for them to establish healthy intimate relationships because of societal norms regarding infidelity and difficulties in having a relationships with individuals from other cultures. Additional norms relating to what constitutes a “healthy” gay intimate relationship may also contribute to the difficult participants had in maintaining intimate relationships. More research is needed to describe the perceptions Hispanic MSM have regarding healthy and unhealthy intimate relationships and how these contribute to risk behaviors. Further, the family is at the center of Hispanic culture. Many Hispanic MSM may lose psychosocial support from their families because of immigration or because of disclosure of sexual orientation. Loss of psychosocial support occurs during the disclosure of sexual orientation because Hispanic families have difficulty accepting homosexuality (Guanero, 2007). In fact, Hispanic families have more negative reactions toward homosexuality than Caucasian families (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). The loss of psychosocial support by the family may result in an increased risk of suicide, depression (Guanero, 2007), substance abuse, and high risk sexual behaviors (Ryan et al., 2009). The loss of psychosocial support and its relationship to intimate partner violence has not been studied among Hispanic MSM, however.

The second category, Las Ramas Enredadas (The Tangled Branches) contain the subcategories of Negation of Sexual Risk, Substance Abuse as a Buffer, and the Burden of Violence. The results contained in the Negation of Sexual Risk is an important finding, as little attention has been paid to the perception of sexual risk among Hispanic MSM. A significant amount of research is available on the risk sexual behaviors of Hispanic MSM, but how these men perceive risk for HIV infection from participation in high risk sexual behaviors has not been explored. Perhaps the participants in this study did not perceive themselves to be at risk for HIV infection, therefore they engaged in high risk sexual behaviors without the knowledge of or regard for the risk of infection. Given this identified gap in the research literature, more research is needed on perception of risk among Hispanic MSM.

Substance Abuse as a Buffer also offers some unique findings with this subpopulation of MSM. Previous research on substance abuse among Hispanic MSM suggested that substance abuse may be related to decreasing sexual inhibitions, connecting with partners, etc. (Bauermeister, 2007; Fernandez et al., 2009). The participants in this study reported that substance abuse was used to buffer the cultural, psychosocial, and social stressors experienced by Hispanic MSM. Since this is a unique finding, more research is needed to further explore this finding.

The Burden of Violence supports existing research that noted the high rates of intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM (Feldman et al., 2007; Feldman et al., 2007). The participants in this study reported that intimate partner violence, much like high risk sex and substance abuse, is rooted in cultural, psychosocial, and social factors that place Hispanic MSM at an increased risk of intimate partner violence. Although not explored in this study, the deeper roots of intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM may be related to childhood sexual abuse (CSA). A study by Arreola and colleagues (2009) suggests that CSA influences high risk sex as well as the risk of violence during adulthood. Given that the participants described violence as a burden among Hispanic MSM, the exploration of CSA influencing the health risk behaviors among this subpopulation of MSM needs further exploration.

The Tangled Branches as described by the participants imply that sexual risk, substance abuse, and violence are co-occurring or overlapping health problems for Hispanic MSM. The study's findings that note this overlapping relationship of these variables that are rooted in cultural, psychosocial, and social factors are consistent with Singer's Syndemic Theory (1996). Consistent with Singer's theory, illnesses or health risks are not mutually-exclusive, but they occur in multiple intersecting clusters that are influenced by social disparities such as poverty, oppression, and stigmatization. In addition, the results of this study are supported by previous studies that examined the syndemic factors among the general population of MSM (Kurtz, 2008), Hispanic women (Gonzalez-Guarda, McCabe, Florom-Smith, Cianelli & Peragallo, 2011) and among Hispanic MSM (De Santis, Arcia, Vermeesch & Gattamorta, 2011).

The results of this study have some clinical implications for nurses and other healthcare providers who work with Hispanic MSM. First, nurses and healthcare providers must address the co-occurring health risks of high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence that may be experienced by Hispanic MSM. Hispanic MSM who are experiencing one of these health disparities could be at an increased risk of experiencing the other disparities. Second, nurses and other healthcare providers need to become comfortable in assessing for these health disparities, as well as the cultural, psychosocial, and social factors that may promote high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. Prompt referral to a mental health professional may be necessary for a more in-depth assessment, as well as assistance with development of coping skills and resources to deal with multiple stressors that may be experienced by these men. Finally, nurse and other healthcare providers must develop, implement and evaluate primary prevention programs that address the root causes of maladaptive behaviors that contribute to the health disparities experienced by Hispanic MSM. These prevention efforts must either reduce these risk factors (e.g, economic difficulties, discrimination) or teach Hispanic MSM to cope more positively to these stressors.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations that need to be addressed in this study. The study's participants may not be representative of the population of Hispanic MSM residing in South Florida. Hispanic MSM who engaged in high risk sex, substance abuse, and who experienced intimate partner violence were over-represented in the focus groups. This over-representation in the focus groups was caused by the fact that participants were encouraged to recruit other participants for the study. Although this method of sampling allows researchers to access hard-to-reach populations such as Hispanic MSM, a weakness is that the sample tends to be more homogeneous and less diverse (Creswell, 2009), which may have affected the study's results.

In addition, the Hispanic population of South Florida is unique in that the majority of South Florida's Hispanics are Cubans, which is different from the rest of the U.S. population of Hispanics. The majority of the Hispanics in the U.S. are of Mexican origin, followed by Puerto Ricans, and then Cubans (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, & Albert, 2011). Considering that the majority of the study's participants were Cuban, the results in this study cannot be generalized to other groups of Hispanic MSM. The use of qualitative research methodology may limit the generalizability of the study's findings (Creswell, 2008); however, the use of grounded theory to explore these phenomena among Hispanic MSM is based on the use of this inductive approach to research. The inductive approach uses specific observations to detect patterns that allow researchers to construct theory based on the assumption that multiple realities and perspective exist for the participants and the researcher. To obtain all possible realities and perspectives, the use of qualitative inquiry is necessary (Glaser, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which may allow a more complete description of unique health risks and the relationships among these health risks that Hispanic MSM as a group experience.

Despite the fact that the study's demographics may not be representative of the profile of Hispanics in the United States, a diverse sample of Hispanic men may add to the clinical applicability of the results. For instance, if the diverse sample of Hispanic men in this study reported issues with sexual risk, substance abuse, and IPV, these health issues may be common among this population of men. These findings have implications for nurse and other healthcare providers who render care to this population. Although at this point it is difficult to examine all the common health issues that occur across all Hispanic MSM subgroups, interventions for clinical care and directions for future research can be developed from this study's findings.

Despite these limitations, new information was gained about a portion of Hispanic MSM at risk for multiple health disparities in terms of sexual risk, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence. The study's findings can generate new research as well as provide directions for clinical practice with Hispanic MSM.

Summary

Hispanic MSM are a vulnerable population at risk for a number of health disparities. The results of this study suggest that Hispanic MSM may engage in high risk sex, substance abuse, and may experience intimate partner violence in tandem. Nurses and other healthcare providers need awareness of these co-occurring conditions that may be experienced by Hispanic MSM. Much more research is needed to understand the causes, consequences, and the complex relationships of these health risks. In addition, research is needed to develop culturally-appropriate interventions to address high risk sex, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic MSM.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (1P60 MD002266-01, N. Peragallo, PI).

References

- Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Diaz R. Childhood sexual abuse and the sociocultural context of sexual risk among adult Latino gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:S432–S438. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA. It's all about “connecting”: Reasons for drug use among Latino gay men living in the San Francisco Bay area. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6(1):109–129. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi FT, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Poppen PJ, Echeverry JJ. A comparison of HIV-related factors among seropositive Brazilian, South American, and Puerto Rican gay men in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behaviors Sciences. 2006;28:450–463. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Dieguez A, Dolezal C, Nieves L, Diaz F, Decena C, Balan I. Looking for a tall, dark, macho man…Sexual-role behavior variations in Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2004;6(2):159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Miler S, McGrath C. Acculturation, drinking and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S.: A longitudinal analysis. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(1):60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] HIV among Hispanics/Latinos. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/index.htm.

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Alegria M, Ortega AN, Takeuchi D. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:785–794. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis J. How do the sexual behaviors of foreign-born Hispanic men who have sex with men differ by relationship status? American Journal of Men's Health. doi: 10.1177/1557988311403299. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis JP. Factors influencing HIV risk among Hispanic men who have sex with men. Hispanic Health Care International. 2010;8(3):122–124. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis JP, Arcia A, Vermeesch A, Gattamorta KA. Using structural equation modeling to identify predictors of sexual behaviors among Hispanic men who have sex with men. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2011;46(2):233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: Data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three US cities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from three US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Heckert AL, Sanchez J. Reasons for stimulant use among Latino gay men in San Francisco: A comparison between methamphetamine and cocaine users. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(S1):i71–i78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. 2010 Census Briefs (C2010BR-04) U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. The Hispanic population: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Changing constructions of machismo for Latino men in therapy: “The devil never sleeps. Family Process. 2010;49(3):309–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MR, Diaz RM, Ream GL, El-Bassel N. Intimate partner violence and HIV sexual risk behaviors among Latino gay and bisexual men. Journal of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Research. 2007;3(2):9–19. doi: 10.1300/J463v03n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MR, Ream GL, Diaz MR, El-Bassel N. Intimate partner violence and HIV sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men: The role of situational factors. Journal of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Research. 2007;3(4):75–87. doi: 10.1080/15574090802226618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MI, Jacobs RJ, Warren JC, Sanchez J, Bowen GS. Drug use and Hispanic men who have sex with men in South Florida: Implications for intervention development. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2009;21(5):45–60. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Ortiz DJ, Martinez V, Bing EG. Sexual solicitation of Latino male day laborers by other men. Salud Publica Mexicana. 2010;50(6):439–450. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000600004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnero PA. Family and community influences on the social and sexual lives of Latino gay men. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1):12–18. doi: 10.1177/1043659606294195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, McCabe B, Florom-Smith A, Cianelli R, Peragallo N. Substance abuse, violence, HIV and depression: An underlying syndemic factor among Latinas. Nursing Research. 2011;60(3):182–189. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318216d5f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Ortega J, Vasquez EP, De Santis JP. La mancha negra: Substance abuse, violence, and sexual risks among Hispanic males. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2011;32(1):128–148. doi: 10.1177/0193945909343594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP. HIV risk, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic females and their partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S. Arrest histories of high-risk gay and bisexual men in Miami: Unexpected additional evidence for syndemic theory. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):513–521. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MA, Champion JD. Motivators of HIV risk-taking behavior among young gay Latino men. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2008;14(4):310–316. doi: 10.1177/1078390308321926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2nd. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Zea MC. Experiences of homonegativity and sexual risk behavior in a sample of Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(1):73–85. doi: 10.1080/13691050903089961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Predictors of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino gay and bisexual men. AIDS & Behavior. 2004;8(4):379–389. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 1996;24(2):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Chenitz W. Why qualitative research in nursing? Nursing Outlook. 1982;30(4):241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Alfonso J, Rodriguez-Madera S. Domestic violence in Puerto Rican gay male couples: Perceived prevalence, intergenerational violence, addictive behaviors, and conflict resolution skills. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(6):639–654. doi: 10.1177/0886260504263873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Diaz RM, Yoshikawa H, Shrout PE. Drug use, interpersonal attraction, and communication: Situational factors as predictors of episodes of unprotected anal intercourse among Latino gay men. AIDS & Behavior. 2009;13:691–699. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9479-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]