Abstract

Of the three nonclassical class I antigens expressed in humans, HLA-F has been least characterized with regard to expression or function. In this study we examined HLA-F expression focusing on lymphoid cells where previous work with homologous cell lines had demonstrated surface HLA-F expression. HLA-F protein expression was observed by western analysis in all resting lymphocytes, including B cells, T cells, NK cells, and monocytes all of which lacked surface expression in the resting state. Upon activation, using a variety of methods to activate different lymphocyte subpopulations, all cell types that expressed HLA-F intracellularly showed an induction of surface HLA-F protein. An examination of peripheral blood from individuals genetically deficient for TAP and Tapasin expression demonstrated the same activation expression profiles for HLA-F but with altered kinetics post activation. Further analysis of CD4+, CD25+ regulatory T cells showed HLA-F was not upregulated on the major fraction of these cells when they were activated, whereas CD4+, CD25- T cells showed strong expression of surface HLA-F when activated under identical conditions. These findings are discussed with regard to possible functions for HLA-F and towards the potential clinical use of HLA-F as a marker of an activated immune response.

Keywords: Activated Lymphocytes, Human, MHC, HLA-F

Introduction

A major genetic determinant of the immune response in general is contained within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). In humans this region includes the classical class I loci HLA-A, -B and -C, whose role in immunological recognition is now well understood [1]. The MHC contains in addition three highly homologous, non-classical class I genes, HLA-E, -F, and -G each of which can be distinguished from classical class I by their expression patterns, and for HLA-E and HLA-G with respect to peptide binding properties and function. HLA-G binds a relatively narrow range of peptides probably serving as structural components rather than for antigen presentation [2] while HLA-E complexes with nonoamer peptide derived from the signal sequence of other MHC class I, including HLA-A, B, C, and G but excluding HLA-F [3]. There is good evidence that the function of HLA-G includes acting as an inhibitory ligand interacting with the ILT2 and ILT4 receptors [4]. HLA-E complexed with nonamer peptide from other MHC class I interacts with the lectin receptor CD94 combined with different NKG2 subunits to inhibit and activate primarily NK cells [5, 6].

The HLA-F locus has very low allelic polymorphism and is highly conserved in distantly related nonhuman primates suggesting a conserved function [7]. Tissue and cell specific mRNA and protein expression has been observed and HLA-F protein was detected on the surface of B cell and some monocyte cell lines and in vivo on extravillous trophoblasts that had invaded the maternal decidua [2, 8]. Evidence of a physical association of HLA-F and TAP was reported [9], but surface expression was not reduced in TAP negative mutant lines [8]. Unlike classical MHC class I, the HLA-F cytoplasmic tail may be required for export from the endoplasmic reticulum implicating a function for HLA-F independent of peptide-loading in the ER [10].

In this study we continued an examination of HLA-F expression, focusing on lymphocyte subsets precursors to cell lines where our previous work had demonstrated protein expression [8]. In addition to B cells where derivative B-LCLs showed surface expression, protein expression but not surface expression was observed in T cells, NK cells and monocytes. By using antibodies that can uniquely distinguish HLA-F among other class I proteins, we were able to distinguish protein expression on resting and activated PBMC subsets. These analyses included comparative measurements on PBMC from individuals deficient in TAP or Tapasin. For T cells we further analyzed HLA-F expression using a number of different methods for lymphocyte activation and were able to distinguish patterns of expression in putative regulatory T cell subsets. This report adds to emerging data on HLA-F expression in the adult immune response, adding focus on this previously little studied human nonclassical class I antigen.

Results

HLA-F is surfaced expressed early after lymphocyte activation

Previous observations of HLA-F surface expression were reported in two papers from this laboratory [2, 8]. HLA-F was expressed on the surface of lymphoblastoid cell lines, which suggested that, since LCLs have some characteristics that overlap with activated B cells, expression might be upregulated in activated B cells. Therefore we examined the expression of HLA-F under activating conditions, examining separately monocytes, B, T, and NK cells before and after activation (Fig. 1). No surface expression on any of the T cell, B cell, or NK cell subsets was seen, despite all of these lymphocyte subsets having HLA-F protein intracellularly. However, after activation, high levels of HLA-F surface expression was observed. At the same time there was no increase in total HLA-F protein upon activation in any of the cell subsets as similar quantities were present before and after activation in all cells examined (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained using either of two distinctly reactive anti-HLA-F reagents, 3D11 and 4A11.

Fig. 1.

HLA-F surface expression is upregulated on the surface of activated PBMC subsets without any corresponding increase in overall cellular protein levels. A) FACS profiles were generated using each of the anti-HLA-F antibodies 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded histogram). Representative profiles are shown before activation (day 0) and 3-5 days after activation as indicated. B) Western analysis of the same cell populations before and 3 days after activation. Cell subtypes are indicated above and below the respective lane for pre-activated and activated cells respectively. Monocytes isolated via CD14 were included in western analysis only.

Because HLA-F protein was present in lymphocytes before activation, we examined the timing of HLA-F surface transport on T cells as a first step towards understanding factors that control surface expression. HLA-F surface expression appeared as early as 30 min and was substantially upregulated 3 hours after T cell stimulation (Fig. 2) preceding by a large margin the initiation of DNA synthesis in activated cells [11]. At 6 hours, 99.5% of the activated CD3+CD8+ T cells remained in G0/G1 (R1) phase and at 19 hours, 8.7% of the cells were in the S (R2) and 8.6% were in the G2/M (R3) phases. HLA-F surface expression also preceded the appearance of the previously described two transcripts for CD25, which are significantly upregulated by 6 hours after activation [12], and the surface expression of activation markers CD25 and HLA-DR, which are upregulated only 12 hours after PMA/ionomycin treatment [13].

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of HLA-F expression and DNA synthesis on CD3+, CD8+ T cells after activation. HLA-F surface expression appears as early as 30 min after T cell activation and increases over 2 days, while DNA synthesis starts at about 19 hrs. Upper: Histograms present FACS analysis of a time course monitoring HLA-F expression on the surface of CD3+, CD8+T cells isolated from peripheral blood and activated with PMA/ionomycin, using anti-HLA-F antibodies 4A11 (solid line), 3D11 (dashed line), anti-HLA-E antibody 3D12 (gray line), and mouse IgG1 (shaded). Differential staining of the two anti-F antibodies is evident over the time course possibly indicating different protein forms of HLA-F are expressed with different kinetics as discussed in the text. Lower: The measurement of cell incorporated BrdU (with FITC antiBrdU) and total DNA content (with 7-AAD) in activated cells. Applying region gates to the 7-AAD versus BrdU dot plot revealed cell subsets that were resided in G0/G1 (R1), S (R2) or G2/M (R3) phases of the cell cycle.

One interesting aspect of early expression was the differential binding of the two HLA-F specific antibodies used. Anti-HLA-F reagent 3D11 detects protein earlier than antibody 4A11, although at later times binding of the two antibodies is essentially equivalent (Fig. 2, far right). We have mapped the epitopes of these antibodies to distinct sites on the protein using mutagenesis and found 3D11 binding to be dependent on residues in the alpha 2 domain while 4A11 binding depends on residues in the alpha 1 protein domain. Supporting this, experiments using either combination of labeled and unlabeled 3D11 and 4A11 indicated the antibodies do not interfere with one another in ELISA (Fig. S1).

HLA-F expressed on activated T cells is glycosylated in a high mannose hybrid-type form

In order to examine the HLA-F protein and to compare the expression of HLA-F on activated cells with previous work on cell lines, we examined HLA-F protein in CD3+CD8+ T cell clones. Two observations were noteworthy. As expected HLA-F expression was upregulated eight days after a clone was stimulated and peaked at day 15 after stimulation was initiated (Fig. 3). After resting a further seven days, HLA-F surface expression was downmodulated. In addition, nearly all of the HLA-F in resting T cells was glycosylated in a high mannose hybrid-type form (Endo H sensitive). In B and monocytes cell lines we previously showed that a minor proportion of HLA-F was present as an Endo H resistant form similar to other MHC class I proteins. However, a similar examination of HLA-F on activated T cell clones demonstrated that most or all of the protein was in fact present as an Endo H sensitive form (Fig. 3, lower), further suggesting that HLA-F may proceed through a pathway distinct from other MHC class I proteins as it is transported to the cell surface.

Fig. 3.

HLA-F surface expression on T cell clones is upregulated after stimulation and downregulated upon resting. Upper: HLA-F expression was measured on the surface of a representative CD3+, CD8+ T cell clone stimulated by anti-CD3 antibody after 8, 12, and 15 days as indicated above each histogram. Cells were then rested for 7 days and tested again for HLA-F expression (indicated above rightmost profile). FACS profiles were generated by staining with each of the anti-F antibodies 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded histogram). Lower: HLA-F is expressed predominantly in an Endo H sensitive form in activated T cell clones. CD3+, CD8+ T cell clones from individuals SA, JNB, and MOL were collected at day 13 after stimulation and at day 7 after resting, lysed and immunoprecipitation was carried out with mAb W6/32. The resultant protein was treated (+) or untreated (-) with Endo H and separated in 11% SDS-PAGE. Western blot was carried out using anti-HLA-F mAb 3D11. HLA-F protein detected in B-LCL cell line 721.221 and monocyte cells 90196B with B-LCL line TM analyzed in parallel as control for Endo H digestion in columns marked C.

The kinetics of surface expression is altered in TAP and Tapasin negative lymphocytes

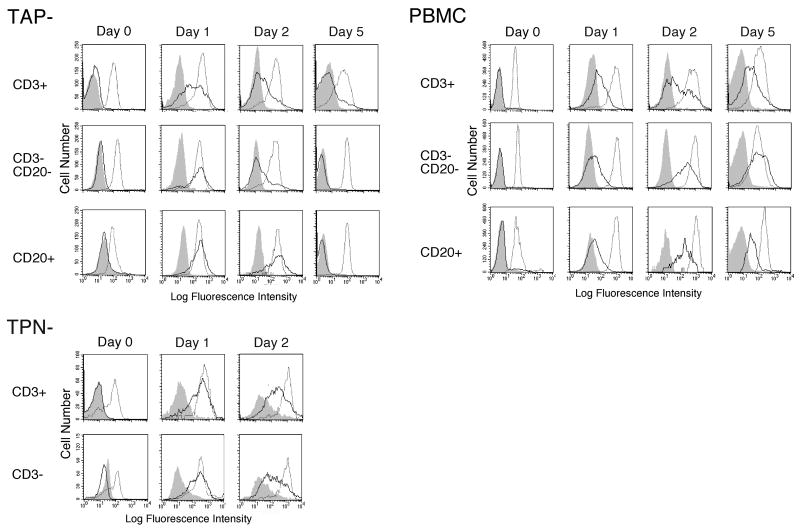

Although there is no evidence that HLA-F normally binds peptide, an examination of HLA-F expression in TAP negative and Tapasin negative B-LCLs did show a partial dependence of HLA-F surface expression on Tapasin, specifically for the Endo H resistant HLA-F protein [8]. In order to examine in vivo expression of HLA-F in this regard, we obtained PBMC from two individuals that are homozygous for null mutations in each of the TAP and Tapasin genes [14, 15]. Using PMA/ionomycin for activation of lymphocytes, upregulation of HLA-F was apparent on TAP- CD3+ cells on day one after stimulation, while cells from a normal individual required up to 5 days before full expression levels were reached (Fig. 4). In fact, active expression of HLA-F on all three cell types was upregulated far sooner than on normal cells peaking on day one on the former versus up to day 5 on the latter. It was not clear why HLA-F expression was downregulated about day 5 after stimulation while cells were still actively dividing. This stands in contrast to our studies with normal PBMC cells where HLA-F surface expression was downmodulated upon resting after activation. An essentially similar picture emerged when Tapasin- PBMC was examined, again with HLA-F expression peaking at day one, and with levels beginning to subside as early as day 2. It was not possible to examine cells beyond this time point due to the small number of cells available and the poor expansion achieved upon activation.

Fig. 4.

HLA-F surface expression presents altered kinetics but not expression levels on TAP and Tapasin (TPN) negative cells in vitro. PBMC from a TAP negative individual [14], a Tapasin negative individual [15], and a normal control was activated with PMA plus ionomycin. FACS profiles were generated using each of the anti-F antibodies 4A11 (solid line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded histogram). Cells were analyzed on days 0, 1, 2 and 5 after stimulation as indicated above the profiles (Tapasin− cells were only analyzed on days 0, 1, and 2). Cell subsets analyzed are indicated to the left of each pair of profiles and the source of the PBMC is indicated to the upper left of each set of FACS profiles as TAP−, TPN− or PBMC indicating normal control cells.

HLA-F is expressed on stimulated memory T cells but not on Treg cells

In order to test if specific lymphocyte activation was able to induce HLA-F surface expression, a precise activation response was examined by using a CMV peptide specific response. PBMC isolated from a CMV+ individual was stimulated by mature dendritic cells loaded with CMV peptide pp65, and stimulated memory T cells were assayed 5 days later by staining with anti-CD25. In this experiment only the memory CD8+ T cells specific for the CMV peptide are activated while CD4+ CD25+ cells present are largely regulatory T cells that have not been not activated. As can be seen in Fig. 5A, all of the activated CD3+CD25+ T cells strongly expressed surface HLA-F while other CD3+CD25- T cells retained the HLA-F null phenotype. Further, it is apparent that HLA-F is not expressed on circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Fig. 5B), nor on pp65/A2 tetramer positive T memory cells before activation (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

HLA-F surface expression on antigen specific activated T cells, CD4+, CD25+ Tregs and A2/pp65 tetramer specific T cells. A) Upper PBMC isolated from CMV+ individual with HLA-A2 haplotype stimulated by mature DCs from the same donor loaded with CMV peptide pp65 were stained with anti-CD25 reagent (vertical) and anti-CD3 antibody (horizontal) to demonstrate antigen specific activation of CMV reactive T cells as previously described [45]. Lower: T cell subsets activated (CD3+, CD25+) and not activated (CD3+, CD25−) which are circled in upper were simultaneously stained with each of the anti-F antibodies 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded histogram). Surface HLA-F was evident only on T cells expressing the activation marker IL-2 receptor alpha chain CD25. B) Upper: Unstimulated PBL obtained from HLA-A2 individual (same donor as for 5A) checked for CD25+, CD4+ T regulatory cell population. Lower: The T regulatory cell subsets (circled in upper) were simultaneously stained with 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded). HLA-F expression was completely absent on this cell subset. C) pp65/A2 tetramer positive T cells were identified from unstimulated PBL as for 5A and 5B (upper) and HLA-surface expression was analyzed by 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded). The data presented in (C) are presented as two-dimentional plots in Fig. S2.

Although HLA-F was not expressed on circulating Tregs, in order to examine HLA-F expression on activated Tregs, we isolated Treg cells using Miltenyi CD4+CD25+ Treg cell isolation kit, and stimulated purified Tregs with anti-CD3 and CD28 antibodies as described [16]. This approach has been shown to specifically enrich for Treg cells as evidenced by costaining with anti-CD25 and anti-Foxp3 yielding ∼80% double positive cells. HLA-F expression was examined after 6 days of activation (Fig. 6A). The analysis of cell surface proteins expressed on the surface of Tregs isolated according to this protocol indicated that over 92% of the cells expressed CD45RO, 94% expressed CD62L and 80% for CD122 (data not shown). As control, CD4+, CD25- cells were isolated from the same donor and stimulated simultaneously with the identical protocol. The activation protocol used was previously shown effective on activation of human CD4+, CD25- and CD4+, CD25+ Treg cells [17]. As expected, CD4+, CD25- T cells were effectively activated and HLA-F expression peaked at day 6 after stimulation. Although the large majority of Tregs did not express HLA-F, a portion of this population did exhibit low surface expression of HLA-F on day 6. These cells may in part be due to contaminating CD4+, CD25- cells remaining after purification and/or differential HLA-F expression on some distinct subpopulations of Tregs [18].

Fig. 6.

The majority of CD4+, CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) do not express surface HLA-F after activation. A) The upper panel shows HLA-F expression on CD4+, CD25- T cells taken from the same individual and stimulated under identical conditions for comparison. Cell populations selected for CD4+, CD25+ and CD4+, CD25- using Miltenyi Microbeads were stimulated with anti CD28 and anti CD3 antibodies using established methods for stimulating Tregs (and CD4+, CD25- T cells) as described in Methods. Relevant FACS profiles form days 0 and 6 are shown as indicated. Cells were stained with 4A11 (solid line) and 3D11 (dashed line), the anti-HLA-E reagent 3D12 (dotted line), and control mouse IgG1 (shaded). B) Cell surface phonotype of the HLA-F positive and negative populations was further analyzed after Treg cells were 6 days after stimulation (from Fig. 6A, bottom right). Cells were double stained with a HLA-F Ab (4A11 or 3D11) and a surface marker (CD69, CD45RO, CD45RA, or HLA-DR). Positive or negative population was first identified and the surface marker, as indicated on each of the upper right corner, was analyzed subsequently by histogram. Solid and dashed line represented 4A11 or 3D11 staining, respectively and shaded area indicates the negative control Ab staining. Numbers in the parenthesis below each surface marker indicate the percentages of negative versus positive cells that express that surface marker in the HLA-F positive and negative populations as indicated. Two-dimentional plots of these data are presented in Fig. S3.

In order to further dissect the activated enriched Treg population, at 6 days of stimulation, the HLA-F positive and negative subsets were separately analyzed for T cell activation markers. In the HLA-F positive fraction (15-20% of total, Fig. 6A lower right) the large majority of cells were CD69, CD45RO, and HLA-DR positive but CD45RA negative, whereas the majority of HLA-F negative population (80-85% of total, Fig. 6A lower right) exhibited a more heterogeneous mixture of phenotypes as demonstrated by expression of CD68 (50%), CD45RO (71%), CD45RA (25%) and HLA-DR (46%). All cells in both populations uniformly expressed CD62L (not shown). Both CD69 and HLA-DR are known markers on activated T cells suggesting that the HLA-F positive fraction may be contaminating normal T cells in the enriched Treg population. The data together suggest that the major fraction of activated Tregs do not express surface HLA-F either before or after activation in contrast to other lymphocyte subsets, including CD4+, CD25- T cells which express high levels of surface HLA-F after activation.

Discussion

This study has examined the expression of HLA-F on the surface of activated lymphocytes and other peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a first step towards understanding HLA-F function. By using antibodies that can uniquely distinguish HLA-F among other class I proteins, we were able to characterize protein expression on activated PBMCs. This follows our characterization of HLA-F expression in placental tissue [2] and extends the scope of research into HLA-F function to the peripheral immune response. It appears that HLA-F expression is coincident with the activated immune response since all B cells, NK cells, monocytes and T cells examined, expressed HLA-F intracellularly and, excepting putative Tregs, surface expressed the protein very early after activation. The lack of HLA-F expression on activated Tregs may also be relevant to function. This report adds to emerging data on HLA-F expression in the adult immune response, possibly contributing focus on this previously little studied human nonclassical class I antigen.

One of the unusual biochemical properties of HLA-F protein on activated lymphocytes is the high mannose hybrid-type glycosylation on most or all of the surface expressed protein. Similar cases of Endo H sensitivity were observed for one of the two glycosylation sites of HLA-DR [19], the HLA-G2, -G3, and -G4 isoforms [20], and for thyroid peroxidase [21], all of which are transported from endoplasmic reticulum (ER), through the Golgi to the cell surface. For classical MHC class I and II molecules, the routes of protein synthesis and peptide loading compartments are essential for binding to and presenting cytosolic and endosomal antigens, respectively. Also of potential relevance, CD1d is expressed on the cell surface as a 45-kDa glycoprotein that is sensitive to Endo H in the absence of β2-m. In contrast, in the presence of β2-m CD1d is expressed on the cell surface as a 48-kDa Endo-H resistant glycoprotein [22]. Although β2-m is present in cells expressing HLA-F, subequimolar amounts of β2-m coimmunoprecipitate with HLA-F suggesting that at least some proportion of the HLA-F protein is expressed without association with β2-m [8]. Other antigen presentation pathways distinct from that used by the MHC class I proteins include those followed by CD1 molecules [23]. In that regard, it is interesting to note that the HLA-F protein cytoplasmic tail, which is modified relative to classical class I due to exclusion of the exon seven sequences from the mature mRNA [24], shares key residues with the CD1d cytoplasmic tail. These residues are part of a signaling mechanism directing interaction the adaptor-3 protein complexes that mediate the endosomal localization of CD1d [25]. Consistent with this possibility, the HLA-F cytoplasmic tail may direct trafficking of HLA-F from the ER through a pathway divergent from classical MHC class I [10].

Although no data have been reported regarding peptide or other ligand binding properties of HLA-F, the predicted dimensions of the groove are similar to those of class I molecules which bind peptides [26]. Indeed, key residues that normally form hydrogen bonds to the peptide N- and C- termini consistent with bound species being peptide are conserved. This consideration combined with other observations suggests the possibility that multiple conformational forms of HLA-F are expressed. Included among those observations is the differential reactivity seen for anti-HLA-F antibodies 3D11 and 4A11 and the subequimolar amounts of β2-m coprecipitated with HLA-F [8]. The simplest conclusion is that at least two forms are being expressed, one β2-m associated and possibly a heavy chain only form possibly similar to MHC class I open conformers [27].

A logical consideration for MHC class I protein expression is the effect of TAP and Tapasin on the regulation of complex assembly and surface expression. In previous examinations using cell lines, TAP-1 antibody and antisera co-immunoprecipitated HLA-F from the HLA-A, B, C class I deficient cell line .221 [9, 28], while similar results from a class I positive B-LCL were less clear [9]. Our previous work showed that surface expression of HLA-F was not affected in TAP deficient B-LCL but there was a modest reduction in Tapasin deficient B-LCL [8]. Using PBL from individuals previously found to lack functional genes for each of TAP and Tapasin we were able to examine the effect of negative expression in vivo. Although no difference in expression levels was found, it was apparent that HLA-F surface expression and subsequent downregulation both occurred sooner than in normal cells. How the altered kinetics of HLA-F expression might affect a normal immune response is not clear from the disease pathogenesis of these two homozygous mutant types. TAP-deficient patients can have serious immune related symptoms including respiratory inflammations and skin ulcers [14]. In one study, a mutation in the TAP2 gene responsible for the defective expression of the TAP complex resulted in the presence of autoreactive natural killer (NK) cells and gamma delta T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood cells of two patients [29]. However, the Tapasin-deficient subject studied in this report has not shown any similar symptoms, or any apparent immune deficiency at all. A more careful examination of HLA-F expression and its potential effect on immune monitoring in these individuals is required before any conclusions about their altered HLA-F expression can be made. Since HLA-F expression is altered in a similar manner in both, it may suggest a common effect on the mechanisms controlling HLA-F expression. At a minimum, this evidence indicates HLA-F expression being independent of TAP and Tapasin, largely consistent with our previous observations on B cell lines [8].

Given the facts about the regulated expression of HLA-F presented here, we are now focused on whether or not HLA-F surface expression on activated lymphocytes, and not on activated Tregs, are facts consistent with a role for HLA-F as part of a signaling mechanism between Tregs and T cells. Since CD4+, CD25+ regulatory T cells are thought to be involved in peripheral tolerance [30, 31] and subsets of Tregs require cell-cell contact for suppressive function to be effective [32], it is conceivable that HLA-F provides a signal that indicates an activated immune response to Treg cells as part of a communication between activated cells and regulatory cells. Such communication could involve stimulation of the regulatory cells to invoke secretion of inhibitory cytokines suppressive of the signaling cells and provoking tolerance, or HLA-F could provide a simple inhibitory signal to the regulatory T cells in order to allow a normal immune response to proceed. The two possibilities are of course not mutually exclusive and the choice might simply depend on the nature of the immune activation and on the nature of the particular Treg subset and on other regulatory signals passed between these cells.

The observation of HLA-F surface expression on decidual extravillous trophoblasts combined with the knowledge of its regulated expression on activated immune cells is suggestive of a further hypothesis that HLA-F is essential for the normal function of trophoblast cells in the decidua. This would suggest that HLA-F is a third necessary partner with HLA-E and HLA-G in the cellular communications that are fundamental to the immunology of pregnancy. If HLA-F does function through an interaction with regulatory T cells, it may be predictive considering other observations of the immune environment within the pregnant mother. Regulatory T cells are found in the human decidual tissue [33-37] where they would be in direct contact with invasive cytotrophoblasts that express surface HLA-F [2]. Further, studies in the mouse have indicated that CD4+, CD25+ regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus [38]. These considerations are suggestive of a role for HLA-F in interactions between placental derived extravillous trophoblasts and regulatory cells in this environment. Either or both inhibitory and activatory roles could be envisioned with the latter presumably linked to stimulation of cytokine release beneficial to pregnancy.

Even before the function of HLA-F is revealed, the expression patterns of HLA-F are suggestive of the potential for development or application of cell and tissue engineering methods to predictably induce tolerance rather than immunity using anti-HLA-F monoclonals. Clinical studies of this type have been reported using a humanized anti-CD25 monoclonal induction therapy in solid organ transplantation to prevent rejection in the early postoperative period with good success [39]. Humanized anti-CD25 was also shown to inhibit disease activity in multiple sclerosis patients [40]. However, as has been pointed out, targeting IL-2 and/or the IL-2R might not be synonymous with blocking or enhancing T-cell immunity since Treg cells might also be affected by these types of therapeutic strategies [41]. Indeed, targeting of CD25+ cells was attempted in marrow transplants to reduce GVHD, but the side effect of removing CD25+ T-regulatory cells at the same time may have caused an unexpected exacerbation of acute GVHD [42]. Since HLA-F is low or not expressed on regulatory T cells, targeting it may have an advantage over some of these approaches, such as in T depleted transplants where T cells are added back after transplant.

Materials and Methods

Cell preparations

Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque. Positive selection for T, B or monocyte cells was performed using CD3-, CD19- or CD14- MicroBeads, an LS+/VS+ column and MidiMACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec). CD3+, CD8+ and CD3+, CD4+ cells were negatively selected using a CD8- and CD4- T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+, CD25+ (Treg) and CD4+, CD25-cells were performed in a two-step isolation procedure using CD4+, CD25+ regulatory T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). This kit has been shown to provide up to 80% enrichment for Tregs as evidence by costaining with CD25-PE and Anti-Foxp3-APC ([43] and MiltenyiBiotec.com). The experiments purifying and stimulating putative Tregs were repeated five times. CD56+, CD3- cells were isolated from PBMCs by two-step immunomagnetic cell sorting. T cells were depleted using mAb against CD3 and then NK cells were enriched from the depleted cell fraction using mAb against CD56. Granulocytes were isolated from whole blood by cell sorting according to their size and granularity. IRB approval for the harvesting of peripheral blod from healthy donors and TAP and Tapasin decificent patients was obtained protocol 89 IR file 118 from the Fred Hutchinson Institutional Review Board. As part of that process, the informed consent of all participating subjects was obtained.

Cell cultures

PBMC from TAP and Tapasin deficient individuals and isolated CD3+, CD8+ or CD3+, CD4+ cells were cultured in RPMI1640-Hepes containing 10% pooled human serum, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 5 U/ml IL-2, 10 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma). CD3+, CD8+ T cell clones (kindly provided by S. R. Riddell) were expanded in RPMI1640-Hepes containing 10% pooled human serum and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, with irradiated 500× LCL and 100× PBMC as feeders and 30 ng/ml OKT3. IL-2 (Chiron) at 50 U/ml was added the next day and fresh medium without OKT3 but with IL-2 was added at day 5. Cells were fed again at day 8 and day 11. To rest T cell clones, cells were washed twice at day 14, cultured in 12-well-plates with T cell clones and PBMC feeder cell numbers at 4 × 106 and 1× 106 respectively, in RPMI1640-Hepes containing 10% pooled human serum and 50 mM beta-mercaptoethanol.

For activation of Tregs, CD4+, CD25+ and CD4+, CD25- control cells were cultured in RPMI 1640-Hepes containing 10% pooled human serum and 2 μg/ml of anti CD28 antibody (BD Pharmingin) at 0.5 × 106/ml, in wells coated with anti CD3 antibody OKT3 at 10 μg/ml [16, 17]. CD19+ cells were stimulated as described previously [44]. Briefly, CD40 ligand (CD40L) transfected NIH 3T3 cells were irradiated at 9600 rads, plated out at 8 × 106 cells per well of 6-well plates. Positive selected CD19+ cells were suspended in Iscoves with 10% pooled human serum, 50 μg/ml transferring (Sigma), 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 15 μg/ml gentamicin, 3.4 ng/ml IL-4 (R & D) and 0.66 μg/ml CSA (Sigma) at 2 × 106 cells/ml. To stimulate CD56+, CD3- cells, two-step immunomagnetic sorted cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% human serum and 25 ng/ml of IL-12 (R & D) at 50 × 104 cells/ml. CD14+ cells were activated in 100 ng/ml of LPS (Sigma) in RPMI-10% pooled human serum at 2-4 × 106 cells/ml. PBMCs obtained from TAP or Tapasin mutant patients were cultured as for CD3+CD4+ cells from normal individuals.

To generate dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes were isolated from PBMC by panning adherent cells on a tissue culture dish in RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 90 min, and culturing in RPMI1640 containing 10% FCS, GM-CSF (Amgen) 800 U/ml and IL-4 (R&D) 1000 U/ml at 3 × 105 cells/ml. Cultures were fed at day 3 and immature DCs were induced to mature DCs by adding 5 ng/ml IL-1β (R&D), 25 ng/ml TNF-α (R&D), 10 ng/ml IL-6 (R&D) and 1 μg/ml PGE2 (Sigma) into culture medium at day 6. Mature DCs were harvested at 24 hr later. To set up stimulation of primary antigen specific T cells [45], mature DCs were induced as above from PBMCs isolated from a CMV+ individual expressing HLA-A2. Cells were preload with 10 μg/ml of pp65 peptide NLVPMVATV (SynPep) for 4 hr, washed once, irradiated at 3000 rad and mixed with PBMC obtained from the same donor at a 1:20 ratio in RPMI1640, 10% pooled human serum. 5 U/ml of IL-2 was added at days 1 and 3. The use of human PBMC for this study was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review committee at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Immunofluorescence staining, cell cycle kinetics, and FACS analysis

Anti-human Abs were purchased from BD Pharmingen unless otherwise described. HLA-F specific mAbs 3D11, 4A11 and HLA-E specific mAb 3D12 were employed in indirect immunofluorescence staining as previously described [8]. Briefly, cells were incubated with saturating concentrations of primary mAbs, followed by washing and labeling with FITC- or PE-conjugated goat F(ab')2 anti-mouse Ig (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA). As indicated in certain experiments, biotinylated Abs at 10 μg/ml were combined with PE labeled pp65/A2 tetramer, CD69-PE (Caltag), CD45RO-PE, CD45RA-PE, HLA-DR-PE, CD3-FITC and CD20-PE or CD4-FITC and CD25-PE, and detected with streptavidin-Cy-Chrome at 1:50 dilutions. Cell-cycle kinetics was determined by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation combined with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) staining according to manufacturers instruction (BD Pharmingen). Briefly, CD3+, CD8+ cells were pulse labeled with 10 μM BrdU during the final one hour of culture at various time points, fixed, permeabilized, treated with DNase to expose BrdU epitopes, stained with FITC-anti-BrdU and 7-AAD. Samples were analyzed on a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Immunoprecipitation, Endo H digestion, and Western blotting

CD3+ CD8+ T cell clones, B-LCL and mono type cell lines were lysed and immunoprecipitated as described with minor modifications [8]. Briefly, cells were collected, washed and lysed at 20 × 106 cells per ml of lysis buffer for an hour on ice. Cell lysate was precleaned extensively with Ig control Ab and protein A-Sepharose. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was adjusted to 0.2% SDS and 1 μg/ml BSA, and W6/32 at 5 μg/ml (final concentration) was added. After continuous mixing at 4°C for 1 hr, 50% of protein A-Sepharose was added at 150 μl/ml and incubated at 4°C for 2 hrs. The immune-complex was washed two times in PBS containing 0.1% SDS and 0.5% BSA, three times with buffer containing 10 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% BSA and 0.5 M NaCl, once in 0.5% NP-40 in PBS, resuspended in Endo H digestion buffer as above and boiled for 5 min. Endo H (Glyco) digestion was conducted according to manufacturer's suggestion. Samples derived from 5 × 105 cells were separated in 11% SDS-PAGE gel and examined by western blot analysis as described [3, 8]. HLA-F protein was detected by mAb 3D11 followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse Ig's (Invitrogen) at 1:5,000 dilutions, and visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL. Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Yuki Moore, Max Topp, and Weidang Li provided helpful discussions and other assistance during the course of this work. T cell clones were kindly provided by Dr. Stan Riddell. We are very grateful to S.M (Tapasin negative) and A.Y. (TAP negative) for their generous gift of blood for this study. We thank Toshio Yabe for his assistance in obtaining PBL from the TAP negative individual. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HD045813 to D.E.G.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- β2-m

β2-microglobulin

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- Endo H

Endoglycosidase H

- Tregs

CD25+ CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors (N.L. and D.E.G.) have filed patents using data published in this paper as partial supporting evidence.

References

- 1.Townsend A, Bodmer H. Antigen recognition by class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:601–624. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishitani A, Sageshima N, Lee N, Dorofeeva N, Hatake K, Marquardt H, Geraghty DE. Protein expression and peptide binding suggest unique and interacting functional roles for HLA-E, F, and G in maternal-placental immune recognition. J Immunol. 2003;171:1376–1384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee N, Goodlett DR, Ishitani A, Marquardt H, Geraghty DE. HLA-E surface expression depends on binding of TAP-dependent peptides derived from certain HLA class I signal sequences. J Immunol. 1998;160:4951–4960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiroishi M, Kuroki K, Rasubala L, Tsumoto K, Kumagai I, Kurimoto E, Kato K, Kohda D, Maenaka K. Structural basis for recognition of the nonclassical MHC molecule HLA-G by the leukocyte Ig-like receptor B2 (LILRB2/LIR2/ILT4/CD85d) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16412–16417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605228103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee N, Llano M, Carretero M, Ishitani A, Navarro F, Lopez-Botet M, Geraghty DE. HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5199–5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser BK, Barahmand-Pour F, Paulsene W, Medley S, Geraghty DE, Strong RK. Interactions between NKG2x immunoreceptors and HLA-E ligands display overlapping affinities and thermodynamics. J Immunol. 2005;174:2878–2884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daza-Vamenta R, Glusman G, Rowen L, Guthrie B, Geraghty DE. Genetic divergence of the rhesus macaque major histocompatibility complex. Genome Res. 2004;14:1501–1515. doi: 10.1101/gr.2134504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee N, Geraghty DE. HLA-F surface expression on B cell and monocyte cell lines is partially independent from tapasin and completely independent from TAP. J Immunol. 2003;171:5264–5271. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wainwright SD, Biro PA, Holmes CH. HLA-F is a predominantly empty, intracellular, TAP-associated MHC class Ib protein with a restricted expression pattern. J Immunol. 2000;164:319–328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle LH, Gillingham AK, Munro S, Trowsdale J. Selective export of HLA-F by its cytoplasmic tail. J Immunol. 2006;176:6464–6472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ertesvag A, Engedal N, Naderi S, Blomhoff HK. Retinoic acid stimulates the cell cycle machinery in normal T cells: involvement of retinoic acid receptor-mediated IL-2 secretion. J Immunol. 2002;169:5555–5563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woerly G, Brooks N, Ryffel B. Effect of rapamycin on the expression of the IL-2 receptor (CD25) Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:322–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy M, Eirikis E, Davis C, Davis HM, Prabhakar U. Comparative analysis of lymphocyte activation marker expression and cytokine secretion profile in stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures: an in vitro model to monitor cellular immune function. J Immunol Methods. 2004;293:127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa H, Yabe T, Akaza T, Tadokoro K, Tohma S, Inoue T, Tokunaga K, Yamamoto K, Geraghty DE, Juji T. Cell surface expression of HLA-E molecules on PBMC from a TAP1-deficient patient. Tissue Antigens. 1999;53:292–295. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.530310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabe T, Kawamura S, Sato M, Kashiwase K, Tanaka H, Ishikawa Y, Asao Y, Oyama J, Tsuruta K, Tokunaga K, Tadokoro K, Juji T. A subject with a novel type I bare lymphocyte syndrome has tapasin deficiency due to deletion of 4 exons by Alu-mediated recombination. Blood. 2002;100:1496–1498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, Ye J, Masteller EL, McDevitt H, Bonyhadi M, Bluestone JA. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1455–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieckmann D, Bruett CH, Ploettner H, Lutz MB, Schuler G. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory, contact-dependent T cells induce interleukin 10-producing, contact-independent type 1-like regulatory T cells [corrected] J Exp Med. 2002;196:247–253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shackelford DA, Strominger JL. Analysis of the oligosaccharides on the HLA-DR and DC1 B cell antigens. J Immunol. 1983;130:274–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riteau B, Rouas-Freiss N, Menier C, Paul P, Dausset J, Carosella ED. HLA-G2, -G3, and -G4 isoforms expressed as nonmature cell surface glycoproteins inhibit NK and antigen-specific CTL cytolysis. J Immunol. 2001;166:5018–5026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuliawat R, Ramos-Castaneda J, Liu Y, Arvan P. Intracellular trafficking of thyroid peroxidase to the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27713–27718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503804200. Epub 22005 May 27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, Garcia J, Exley M, Johnson KW, Balk SP, Blumberg RS. Biochemical characterization of CD1d expression in the absence of beta2-microglobulin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9289–9295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geraghty DE, Wei XH, Orr HT, Koller BH. Human leukocyte antigen F (HLA-F). An expressed HLA gene composed of a class I coding sequence linked to a novel transcribed repetitive element. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton AP, Prigozy TI, Brossay L, Pei B, Khurana A, Martin D, Zhu T, Spate K, Ozga M, Honing S, Bakke O, Kronenberg M. The mouse CD1d cytoplasmic tail mediates CD1d trafficking and antigen presentation by adaptor protein 3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:3179–3186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Callaghan CA, Bell JI. Structure and function of the human MHC class Ib molecules HLA-E, HLA-F and HLA-G. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:129–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arosa FA, Santos SG, Powis SJ. Open conformers: the hidden face of MHC-I molecules. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lepin EJ, Bastin JM, Allan DS, Roncador G, Braud VM, Mason DY, van der Merwe PA, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Powis SH, O'Callaghan CA. Functional characterization of HLA-F and binding of HLA-F tetramers to ILT2 and ILT4 receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3552–3561. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200012)30:12<3552::AID-IMMU3552>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moins-Teisserenc HT, Gadola SD, Cella M, Dunbar PR, Exley A, Blake N, Baykal C, Lambert J, Bigliardi P, Willemsen M, Jones M, Buechner S, Colonna M, Gross WL, Cerundolo V. Association of a syndrome resembling Wegener's granulomatosis with low surface expression of HLA class-I molecules. Lancet. 1999;354:1598–1603. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bour-Jordan H, Bluestone JA. Regulating the regulators: costimulatory signals control the homeostasis and function of regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:41–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corthay A. How do regulatory T cells work? Scand J Immunol. 2009;70:326–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shevach EM. Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity*. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heikkinen J, Mottonen M, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of regulatory T cells in the human decidua. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Izcue A, Powrie F. Prenatal tolerance--a role for regulatory T cells? Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:379–382. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito S, Nakashima A, Myojo-Higuma S, Shiozaki A. The balance between cytotoxic NK cells and regulatory NK cells in human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;77:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito S, Shiozaki A, Sasaki Y, Nakashima A, Shima T, Ito M. Regulatory T cells and regulatory natural killer (NK) cells play important roles in feto-maternal tolerance. Semin Immunopathol. 2007;29:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s00281-007-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasaki Y, Sakai M, Miyazaki S, Higuma S, Shiozaki A, Saito S. Decidual and peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in early pregnancy subjects and spontaneous abortion cases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:347–353. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:266–271. doi: 10.1038/ni1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiland AM, Philosophe B. Daclizumab induction in solid organ transplantation. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:729–740. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schippling DS, Martin R. Spotlight on anti-CD25: daclizumab in MS. Int MS J. 2008;15:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin PJ, Pei J, Gooley T, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Deeg J, Hansen JA, Nash RA, Petersdorf EW, Storb R, Ghetie V, Schindler J, Vitetta ES. Evaluation of a CD25-specific immunotoxin for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after unrelated marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikawa H, Qian F, Tsuji T, Ritter G, Old LJ, Gnjatic S, Odunsi K. Influence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells on low/high-avidity CD4+ T cells following peptide vaccination. J Immunol. 2006;176:6340–6346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kondo E, Topp MS, Kiem HP, Obata Y, Morishima Y, Kuzushima K, Tanimoto M, Harada M, Takahashi T, Akatsuka Y. Efficient generation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells using retrovirally transduced CD40-activated B cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:2164–2171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonini C, Lee SP, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Targeting antigen in mature dendritic cells for simultaneous stimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5250–5257. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.