Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility and perceived benefits of conducting physician-parent follow-up meetings after a child’s death in the PICU according to a framework developed by the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN).

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Seven CPCCRN affiliated children’s hospitals.

Subjects

Critical care attending physicians, bereaved parents, and meeting guests (i.e., parent support persons, other health professionals). Interventions: Physician-parent follow-up meetings using the CPCCRN framework.

Measurements and Main Results

Forty-six critical care physicians were trained to conduct follow-up meetings using the framework. All meetings were video recorded. Videos were evaluated for the presence or absence of physician behaviors consistent with the framework. Present behaviors were evaluated for performance quality using a 5-point scale (1=low, 5=high). Participants completed meeting evaluation surveys. Parents of 194 deceased children were mailed an invitation to a follow-up meeting. Of these, one or both parents from 39 families (20%) agreed to participate, 80 (41%) refused, and 75 (39%) could not be contacted. Of 39 who initially agreed, three meetings were canceled due to conflicting schedules. Thirty-six meetings were conducted including 54 bereaved parents, 17 parent support persons, 23 critical care physicians and 47 other health professionals. Physician adherence to the framework was high; 79% of behaviors consistent with the framework were rated as present with a quality score of 4.3±0.2. Of 50 evaluation surveys completed by parents, 46 (92%) agreed or strongly agreed the meeting was helpful to them and 40 (89%) to others they brought with them. Of 36 evaluation surveys completed by critical care physicians (i.e., one per meeting), 33 (92%) agreed or strongly agreed the meeting was beneficial to parents and 31 (89%) to them.

Conclusions

Follow-up meetings using the CPCCRN framework are feasible and viewed as beneficial by meeting participants. Future research should evaluate the effects of follow-up meetings on bereaved parents’ health outcomes.

Keywords: Intensive care, Pediatrics, Parents, Physicians, Bereavement, Death, Follow-up

INTRODUCTION

Many professional organizations in the United States (US) recommend follow-up meetings between physicians and family members after a patient’s death as part of routine care (1–4). Parents whose children die in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) are at high risk for bereavement related complications (5–8) and may potentially benefit from a follow-up meeting. Physicians and other health professionals familiar with the patient may help parents understand their child’s illness and death in ways that promote healthy adjustment.

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) previously evaluated the perspectives and experiences of bereaved parents and critical care physicians regarding follow-up meetings after a child’s death in a PICU (9–10). This research suggests that many bereaved parents desire a follow-up meeting with their child’s critical care physician to gain information, reassurance, and an opportunity to provide feedback on their hospital experiences. Additionally, many critical care physicians are willing to conduct follow-up meetings with parents and staff and believe follow-up meetings are beneficial. However, our prior research also suggests that follow-up meetings rarely occur (9). For example, although 59% of parents reported wanting a follow-up meeting with their child’s critical care physician, only 13% met with any physician to discuss their child’s death.

Based on our prior research, the CPCCRN developed a framework for conducting follow-up meetings with bereaved parents after a child’s death in the PICU (11). The framework is a general set of principles intended to guide follow-up meetings and includes processes and content adaptable to the specific context of each family’s circumstances. The objective of the current study is to assess the feasibility and perceived benefits of conducting follow-up meetings after a child’s death according to the CPCCRN framework. Outcomes include parent participation rates, physician adherence to the framework, and parent, physician and other health professional evaluations of follow-up meetings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective observational study of physician-parent follow-up meetings was conducted across the CPCCRN (12–15). The CPCCRN is a multi-center research network consisting of 7 US tertiary care academic pediatric centers and a data coordinating center. The CPCCRN is funded by the NICHD to conduct collaborative clinical trials and descriptive studies in pediatric critical care medicine. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site and the data coordinating center. Informed consent and self-reported demographics were obtained from all participants. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the NICHD to protect identifiable research information from forced disclosure (16).

CPCCRN Framework

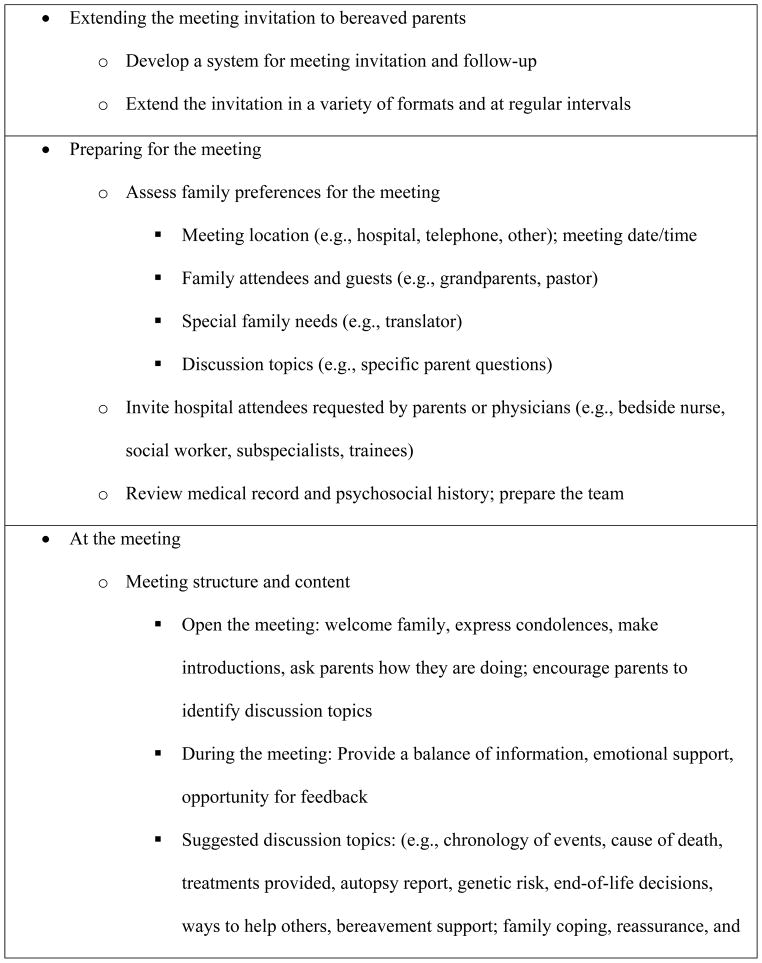

The framework is based on prior CPCCRN research investigating bereaved parents’ and critical care physicians’ perspectives and experiences with follow-up meetings (9–11). Using a semi-structured interview approach, parents whose children died in a PICU were asked about their desire to meet with their child’s critical care physician following the death, and their preferences for meeting time, location, participants and discussion topics (9). Using a similar approach, critical care physicians were asked about their past experiences participating in follow-up meetings, perceived benefits and barriers to meeting, and how future meetings should ideally be conducted (10). Interview transcripts were analyzed inductively from a constructivist stance (17) and important processes and content for follow-up meetings were identified and serve as the basis for the framework (11). The framework includes suggestions for extending a meeting invitation, preparing for a meeting, meeting structure and content, communicating effectively, and follow-up after the meeting (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework for physical-parent folloe-up meetings.

Participants

Study participants included critical care attending physicians, bereaved parents, and meeting guests invited by physicians or parents. Critical care attending physicians were eligible if they were practicing at a CPCCRN PICU, willing to be trained to use the follow-up meeting framework, and not directly involved with prior development of the framework. Parents (i.e., biological and/or legal guardians) were eligible if their child died in a CPCCRN PICU, if they were English or Spanish speaking, ≥18 years of age, and if a critical care physician trained to use the framework participated in their child’s care. Guests were individuals whose presence at the follow-up meeting was requested by parents or physicians including parent support persons (e.g., relatives) who were ≥18 years of age and other health professionals (e.g., subspecialist, social worker, nurse).

Recruitment and training of critical care physicians

Critical care attending physicians were recruited at each site by a research coordinator. Two investigators (KLM and SE) trained physician participants to use the CPCCRN follow-up meeting framework (11) via face-to-face or web-based small group sessions. Training included a lecture on the health consequences of bereavement and an explanation of key aspects of using the framework emphasizing the structure and content of follow-up meetings and suggestions for communicating effectively (see CPCCRN framework, described above). Training included a viewing of three simulated follow-up meetings, interactive discussion, and a question and answer period. The simulations were created with actors and illustrated meetings following diverse types of PICU deaths.

Recruitment of parents and meeting guests

Eligible parents were identified at each site by review of PICU logs for deaths occurring in the preceding month and consultation with participating physicians. Deceased children’s medical records were reviewed to obtain the parents’ primary language and contact information. Eligible parents were mailed a letter approximately one month after their child’s death that expressed condolences and invited them to participate in a follow-up meeting as part of a research study. Letters were in English or Spanish depending on the parents’ primary language. Research coordinators contacted eligible parents via telephone one to two weeks later to recruit them to the research. Research coordinators explained the study purpose and procedures and answered parents’ questions about the research. If a parent agreed to participate in the research, research coordinators elicited parents’ preferences for meeting (e.g., desired date and time, meeting participants, discussion topics) and scheduled follow-up meetings. Parents who agreed to participate were offered the opportunity to invite guests from their family or community to attend the follow-up meeting and to identify other health professionals they would like to be present. Research coordinators invited health professionals whose presence was requested by the parents or the critical care physician.

Follow-up meetings

Follow-up meetings were conducted at the hospital where the child died in a conference room away from the PICU or at another on-campus location. The research coordinator met the parents and their guests on arrival, escorted them to the conference room, assisted with the completion of consent documents, and remained with parents until the meeting began. A critical care physician conducted each follow-up meeting according to the CPCCRN framework (11) and training described above. Follow-up meetings were intended to last about 1 hour. At the close of the meeting, research coordinators escorted parents to the hospital lobby or exit. All follow-up meetings were video-recorded.

Post-meeting surveys

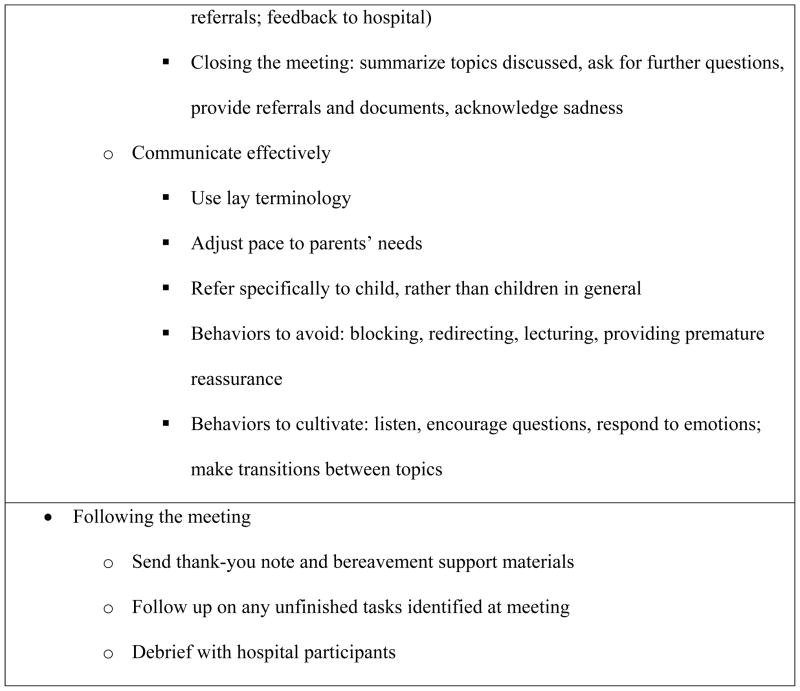

Parents, critical care physicians and other health professionals participating in each follow-up meeting were asked to complete a brief investigator-developed survey within one week of the meeting (Figure 2; Supplemental Digital Content 1). Critical care physicians and other health professionals completed a separate survey for each meeting in which they participated. Surveys were designed to elicit participants’ perspectives on the meeting and survey items varied by type of participant (i.e., parent, critical care physician, other health professional). Surveys included items with a Likert-style response format (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) and items with a brief open-ended response format. Parent surveys were administered by a research coordinator via telephone. Coordinators read the survey items and recorded parents’ responses in writing. Closed-ended responses were recorded verbatim and open-ended responses were paraphrased. Physician and other health professional surveys were written.

Data Analysis

Description of participants and meetings

Participant and meeting characteristics were summarized as absolute counts and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Parent participation rate was calculated as the proportion of families mailed invitations from which at least one parent participated in a follow-up meeting.

Physician adherence to the framework

All video recordings of follow-up meetings were transcribed verbatim. An investigator (SE) trained two research assistants to evaluate the presence and quality of physician behaviors consistent with the framework. Training involved reading the framework (11), discussing definitions and examples of each physician behavior, and reviewing three videos and accompanying transcripts together. Once training was complete, both research assistants reviewed each video and transcript to rate physician behaviors using a 20-item checklist (Figure 3; Supplemental Digital Content 2). Each behavior on the checklist was categorized as one of the following: 1 (present), 0 (absent), NA (not appropriate) or NR (not ratable). NA occurred if the behavior represented by the item was not present and would have been inappropriate in the context of the particular meeting and family. NR occurred if the quality of the recording was compromised such that a behavior could not be identified or judged. Next, both research assistants scored the quality of performance of each present behavior using a 5-point scale (1=low quality, 5=high quality). After initial scoring of the videos, discrepancies between the research assistants were reviewed. If the research assistants were discrepant in whether a behavior was present, absent, NA or NR, or if the quality scores were more than one point apart, they reviewed and discussed the video and transcript together to reach consensus. If the quality scores were discrepant but within one point of each other, the average of the two scores was used.

The extent to which physicians performed each behavior on the checklist was summarized by item as the absolute count and percentage of all meetings in which the item was performed. The quality of performance of each present behavior was summarized by item as the mean and standard deviation of all quality scores obtained for the item. Overall adherence was summarized for each meeting as the percentage of items present out of all items that were appropriate and ratable. Overall quality of performance was summarized for each meeting as the mean and standard deviation of quality scores for present items.

Meeting evaluation surveys

Likert-style survey responses were summarized by item as the absolute count and percentage in each response category, excluding missing or not applicable responses. Responses to open-ended survey items were analyzed inductively. Two investigators (KLM and SE) used an iterative process which included independent reading of the responses to identify themes, comparison of themes between investigators, and re-reading of responses and discussion to refine themes and reach consensus. Examples of each theme are presented.

Sample size

In this pilot study of feasibility, we planned to recruit participants until about 35 physician-parent follow-up meetings had been conducted across the CPCCRN. This number of meetings was anticipated to provide sufficient data and representation from each of seven sites (approximately 5 meetings per site) to allow the investigators to refine the framework and determine feasibility of testing the framework in a larger trial.

RESULTS

Forty-six critical care attending physicians were trained to conduct follow-up meetings as described by the CPCCRN framework. Parents of 211 deceased children were eligible to participate in a follow-up meeting; parents of 194 were mailed invitations. Reasons for not inviting eligible parents included lack of contact information or only out-of-state or international addresses available (n=4), parent incarceration (n=1), and physician preference not to meet because of potential litigation (n=3), suspected child abuse (n=3), lack of familiarity with parents (n=2), patient not residing with parents prior to death (n=1), prior occurrence of a follow-up meeting with a critical care physician outside of the study (n=1), or no reason provided (n=2).

Of the 194 families who were mailed invitations, one or both parents from 39 families (20%) agreed to a follow-up meeting, 80 (41%) refused, and 75 (39%) were unable to be contacted. Of the 39 families who initially agreed to a follow-up meeting, three were cancelled due to conflicting schedules. A total of 36 follow-up meetings were conducted including 54 bereaved parents, 17 parent support persons, 23 critical care attending physicians and 47 other health professionals. Demographics of study participants are listed in Table 1. Most bereaved parents were Caucasian females. Most critical care physicians were Caucasian; about half were male. Of the 47 other health professionals, 32 (68%) were invited at the parents’ request and 15 (32%) at the critical care physicians’ request. Each critical care physician conducted 1–3 follow-up meetings. Children of participating parents were 6.8 ± 6.9 years of age at the time of death; 18 (50%) were male; and 10 (28%) died from multiple organ failure, 8 (22%) cardiac causes, 7 (19%) respiratory causes, 4 (11%) neurologic causes, 3 (8%) malignancy, 3 (8%) trauma (two suspected abuse) and 1 (3%) gastrointestinal causes. Follow-up meetings took place 14.5 ± 6.3 weeks after the child’s death and were 1.2 ± 0.6 hours duration. Thirty-three (92%) meetings were conducted in English and 3 (8%) in Spanish (with the assistance of a translator). Video recording was attempted for all follow-up meetings however during one meeting the camera malfunctioned and the video was lost. Rating of the video recordings and accompanying transcripts showed that critical care physicians performed 12 of the 20 behaviors consistent with the framework in ≥ 89% of the meetings (Table 2). Mean quality scores were ≥4 for 17 of the 20 behaviors. Overall adherence to the framework (when behaviors were both ratable and appropriate in the context of the meeting) was 79% and overall quality of present behaviors was 4.3 ± 0.2.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Parents (N=54) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 37.7 ± 9.7 |

| Relationship to child, n (%) | |

| Biological mother | 33 (61) |

| Biological father | 21 (39) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 40 (74) |

| Black or African American | 7 (13) |

| Other | 6 (11) |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 8 (15) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 40 (74) |

| Unknown or not reported | 6 (11) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 39 (72) |

| Not married | 15 (28) |

| Critical care physicians (N=23) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 41.0 ± 7.8 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 12 (52) |

| Female | 11 (48) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 18 (78) |

| Black or African American | 1 (4) |

| Other | 2 (9) |

| Unknown or not reported | 2 (9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (9) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 20 (87) |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (4) |

| Other health professionals (N=47) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 44.1 ± 14.3 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 10 (21) |

| Female | 37 (79) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 41 (87) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2) |

| Other | 4 (8) |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (4) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 41 (87) |

| Unknown or not reported | 4 (9) |

| Professional background, n (%) | |

| Physician | 18 (38) |

| Social worker | 15 (32) |

| Nurse | 6 (13) |

| Chaplain | 5 (11) |

| Other | 3 (6) |

Table 2.

Physician Adherence to Framework Behaviors (N=35 video-recorded meetings)

| Behavior a | Present b n (%) | Absent c n (%) | Not Appropriate d n (%) | Not Ratable e n (%) | Quality score f Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening the meeting | |||||

| Welcome the family | 20 (57) | 5 (14) | 0 | 10 (29) | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| Express condolences | 23 (66) | 6 (17) | 0 | 6 (17) | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

| Make introductions | 16 (46) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 14 (40) | 4.1 ± 0.8 |

| Ask parents how they are doing | 13 (37) | 20 (57) | 0 | 2 (6) | 3.9 ± 0.8 |

| Encourage parents to identify discussion topics | 32 (91) | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (6) | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| Make transition to meeting content | 13 (37) | 20 (57) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3.7 ± 0.8 |

| During the meeting | |||||

| Cover a balance medical, social, emotional topics | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| Make transitions between topics | 1 (3) | 34 (97) | 0 | 0 | 3.0 |

| Encourage questions | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 ± 0.5 |

| Be responsive to questions and concerns | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.6 ± 0.4 |

| Encourage feedback | 31 (89) | 4 (11) | 0 | 0 | 4.6 ± 0.7 |

| Acknowledge emotions | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.1 ± 0.5 |

| Provide reassurance | 34 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Use terminology parents can understand | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.3 |

| Set a comfortable pace | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| Provide information in short segments | 34 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| Tailor discussion to the specific family | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.7 ± 0.4 |

| Closing the meeting | |||||

| Summarize discussion | 4 (11) | 29 (83) | 0 | 2 (6) | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Ask for further questions | 14 (40) | 14 (40) | 5 (14) | 2 (6) | 4.5 ± 0.6 |

| Clarify next steps and provide referrals | 31 (89) | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (9) | 4.2 ± 0.7 |

Each behavior on the checklist was categorized as one of the following: Present, Absent, Not Appropriate or Not Ratable for each of 35 video-recorded meetings.

Present = behavior was observed;

Absent = behavior was not observed but would have been appropriate in the context of the meeting;

Not Appropriate = behavior was not observed and would not have been appropriate in the context of the meeting;

Not Ratable = behavior could not be identified or judged because the quality of the recording was compromised.

Quality of performance of each present behavior was scored using a 5-point scale (1=low quality, 5=high quality).

Fifty meeting evaluation surveys were completed by parents (Table 3). Of these, 46 (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that the meeting was helpful to them, 40 (89%) that the meeting was helpful to others they brought with them (when applicable), and 39 (78%) that the meeting will help them to cope in the future. Thirty-six meeting evaluation surveys were completed by critical care physicians (i.e., one per meeting). Of these, 27 (75%) agreed or strongly agreed that they adhered to the follow-up meeting framework and 33 (92%) that the framework was easy to use. Thirty-three (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that the meeting was beneficial to parents, and 31 (89%) that the meeting was beneficial to them. Forty-six meeting evaluation surveys were completed by other health professionals. Of these, 40 (89%) agreed or strongly agreed that the meeting was beneficial to parents, and 39 (85%) that the meeting was beneficial to them.

Table 3.

Meeting Evaluation Surveys

| Item | N | StronglyDisagree n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Agree n (%) | Strongly agree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent surveys (N=50) | ||||||

| The information discussed at the meeting was important to me | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 9 (18) | 38 (76) |

| The information was discussed in a way that I could understand it | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 8 (16) | 40 (80) |

| I had the opportunity to ask the questions that I wanted to ask | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 6 (12) | 42 (84) |

| I felt emotionally supported at the meeting | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (4) | 7 (14) | 39 (78) |

| I had the opportunity to provide feedback about my hospital experience | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | 8 (16) | 40 (80) |

| The meeting was helpful to me | 50 | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (4) | 9 (18) | 37 (74) |

| The meeting was helpful to the other people I brought with me (if applicable) | 45 | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (9) | 12 (27) | 28 (62) |

| The meeting will help me in the future to cope with the loss of my child | 50 | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 8 (16) | 10 (20) | 29 (58) |

| Critical care physician surveys (N=36) | ||||||

| I adhered to the framework during the follow-up meeting | 36 | 0 | 1 (3) | 8 (22) | 24 (67) | 3 (8) |

| The framework was easy to use | 36 | 0 | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 22 (61) | 11 (31) |

| The framework helped me to achieve my goals for the meeting | 36 | 0 | 0 | 8 (22) | 20 (56) | 8 (22) |

| The framework helped me to address the parents’ needs during the meeting | 36 | 0 | 0 | 9 (25) | 19 (53) | 8 (22) |

| The meeting was beneficial to the parents | 36 | 0 | 0 | 3 (8) | 12 (33) | 21 (58) |

| The meeting was beneficial to other family members (if applicable) | 16 | 0 | 0 | 2 (13) | 7 (44) | 7 (44) |

| The meeting was beneficial to other healthcare providers (if applicable) | 28 | 0 | 1 (4) | 8 (29) | 10 (36) | 9 (32) |

| The meeting was beneficial to me | 35 | 0 | 0 | 4 (11) | 16 (46) | 15 (43) |

| Other health professional surveys (N=46) | ||||||

| The information discussed at the meeting was important to the parents | 45 | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 | 8 (18) | 34 (76) |

| The information was discussed in a way the parent could understand it | 46 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 6 (13) | 38 (83) |

| The parents had the opportunity to ask questions | 46 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (7) | 41 (89) |

| The parents were emotionally supported at the meeting | 46 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 10 (22) | 33 (72) |

| The parents had the opportunity to provide feedback about their hospital experience | 46 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (7) | 41 (89) |

| The meeting was beneficial to the parents | 45 | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 9 (20) | 31 (69) |

| The meeting was beneficial to other family members (if applicable) | 24 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 6 (25) | 13 (54) |

| The meeting was beneficial to the physician(s) | 44 | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 19 (43) | 19 (43) |

| The meeting was beneficial to me | 46 | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 15 (33) | 24 (52) |

Parents’ responses to open-ended survey items described aspects of the meeting parents perceived as most helpful including the opportunity to gain information, receive emotional support, and provide feedback, as well as the honest, unhurried and non-threatening style of communication (Table 4; Supplemental Digital Content 3). Parents’ comments pertaining to the least helpful aspects of the meeting included the need for additional information that was not available or communicated clearly and the desire for different support staff at the meeting than those who attended.

Table 4.

Parents Views on the Most and Least Helpful Aspects of the Meeting

| Most helpful | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Example a |

| Information | |

| Gain new information | For us specifically, we found out a lot more information about our son than the information presented during our hospital time. |

| Validate prior understanding | It helped me to verify what I had thought was the case. The doctor verified what I had thought. |

| Ask questions | I had lingering questions that I would go over again and again and now they are all answered. |

| Emotional support | |

| Express emotions | Time was created for me just to talk and open up…I was able to open up and express feeling. |

| Feel supported | The doctors were supportive and cared. The doctors knew my son and showed their concern. |

| Gain reassurance | I was reassured that we made the right decisions…the doctors felt that we made the right decisions too. That was good to know. |

| Reconnection | It was nice to see Dr. N- and give me a chance to think about the most important time of my life, to thank her. Also, it was good to come back to the hospital, brought back good memories, it was my daily routine. |

| Provide feedback | I could talk about my likes and dislikes which I didn’t do as much in the hospital. I had an opportunity a lot of people don’t have a chance to do. I was able to say what I thought. |

| Meeting Style | |

| Pace | I was not rushed at the meeting. I did not feel like I was inconveniencing anyone. |

| Atmosphere | Peaceful atmosphere. No pressure. Not a lot of overcrowding. Not a bunch of people there. |

| Communication | The doctor did not withhold any information. He did it in terms we could understand. |

| Least helpful | |

| Theme | Example |

| Lack of information | In our situation, we really still don’t have an answer as to what happened to her. |

| Selection of meeting attendees | Maybe there would have been other people there that may have been helpful too. I know that you told us we could request others but we did not give that too much thought prior to the meeting. |

Examples are paraphrased comments from parents collected from telephone evaluation surveys

Physicians’ responses to open-ended survey items described aspects of the framework that were most useful in conducting follow-up meetings. These included having a system for inviting parents and arranging the meeting and having a structure to guide the meeting (Table 5; Supplemental Digital Content 4). Regarding least useful aspects, some physicians suggested more structure to the meeting would be helpful for those inexperienced with follow-up meetings. Physicians’ responses to open-ended survey items also described aspects of the meeting felt to be most beneficial to parents and physicians. Physicians reported their belief that parents benefited from the information and reassurance provided during the meeting and that physicians benefited by reconnecting with parents, gaining a deeper understanding of parents’ perspectives, and achieving a sense of closure (Table 6; Supplemental Digital Content 5). Other health care professionals’ responses to open-ended survey items mirrored the comments of parents and physicians.

Table 5.

Physicians’ Views on Most and Least Useful Aspects of the Framework

| Most useful | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Example a |

| Invitations and arrangements | It was helpful that all the arrangements were made that then allowed the meeting to take place. |

| Structure | The structure of the framework is most helpful. It allows appropriate time for the materials covered. |

| Least useful | |

| Theme | Example |

| Insufficient structure | I felt it was not extremely structured. Less structure is useful for someone used to running follow-up meetings with families but might be more difficult for a neophyte. |

Examples are direct quotes from physicians collected from written evaluation surveys

Table 6.

Physicians’ Views on Beneficial Aspects of the Meeting for Parents and Physicians

| Benefits for parents | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Example a |

| Information | It provided them another opportunity to discuss the medical situation; they stated it helped them understand‘the blur’ of the hospital admission. |

| Reassurance | I think that they now understand that there is nothing more they could have done to prevent their child’s death; that they didn’t ‘fail to bring him sooner’. |

| Benefits for physicians | |

| Theme | Example |

| Reconnection | Privilege to reconnect with family. Do not get that opportunity otherwise. |

| Deeper understanding | I was able to hear from a family’s perspective and views. It is amazing to realize things we do everyday can be so misunderstood. |

| Closure | It gave me closure. I would highly recommend meeting with parents and families following the loss of a loved one. |

Examples are direct quotes from physicians collected from written evaluation surveys

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that it is feasible to conduct physician-parent follow-up meetings after a child’s death in the PICU. Critical care physicians were willing to be trained to use the CPCCRN follow-up meeting framework. Overall adherence to the framework was strong (79%) and behaviors consistent with the framework were enacted with high quality. Other health professionals such as subspecialists, social workers, nurses, chaplains and others routinely participated in follow-up meetings when requested by parents or physicians. Physicians’, parents’ and other health professionals’ views of their follow-up meeting experiences were generally favorable. Benefits to both family members and professionals attending the meetings were identified.

Twenty percent of families that were mailed invitations (33% of those able to be contacted) agreed to participate in a follow-up meeting with a critical care physician after their child’s death. This participation rate is similar to the rates observed in other bereavement research conducted by the investigators (7, 9, 18). However, reports describing physician-parent follow-up meetings offered as part of clinical care typically report parent participation rates greater than 50% (19–21). Although the CPCCRN framework aims to accommodate parents’ preferences for meeting such as timing of the meeting, invited guests and discussion topics (11), it may be that parents are more likely to participate in a follow-up meeting when offered outside of a research context. Research procedures such as video recording may be stressful for parents and thereby deter meeting participation.

Critical care physicians’ adherence to the CPCCRN follow-up meeting framework was strong overall. However certain behaviors were found to be poorly adhered to or not ratable by video analysis. Most of these behaviors were associated with opening the meeting and their absence on the videos is likely a methodological issue. For example, in some cases, physicians and other health professionals welcomed the family, expressed condolences, made introductions and asked parents how they were doing while in the hallway before entering the conference room where cameras were set up; therefore these behaviors were not captured on the video recordings. In other cases, cameras were turned on after the conversation had begun.

One physician behavior prescribed by the framework, “make transitions between topics”, was present in only one of the videos with a quality score of 3. An example of a transition statement provided to physicians during training was as follows: “If you feel comfortable with what we’ve discussed about what happened the night Ray died, I’d like to spend some time talking about the other questions that you have for me. Before we move on, do you have other questions? We can always come back to this topic if you think of other questions” (11). Another physician behavior prescribed by the framework to occur during closing of the meeting, “summarize discussion,” was also often absent. Despite the lack of formal transitions and summary statements, most parents (96%) agreed or strongly agreed with the item on the meeting evaluation survey that information was discussed in a way that they could understand it. Based on published literature regarding communication skills during physician-patient interactions (22, 23), the investigators believe that organizing strategies such as making transitions, providing summaries, and confirming parents’ understanding can be useful to provide and reiterate important information in a way that can be understood. Physicians did, however, encourage and respond to parents’ questions during the meetings as prescribed by the framework. It may be that this communication strategy compensated for the lack of transitions and summary statements, and contributed to parents’ satisfaction with the way information was discussed.

Meeting evaluation surveys completed by parents, critical care physicians and other health professionals suggest overall satisfaction with the CPCCRN follow-up meeting framework. Seventy-five percent of critical care physicians agreed or strongly agreed they adhered to the framework consistent with overall adherence of 79% determined by research assistants via video analysis. Importantly, most parents, physicians and other health professionals reported their belief that follow-up meetings were beneficial for all types of participants. Most parents reported their belief that follow-up meetings would help them cope in the future. However, these perceived benefits should be objectively assessed in future research.

Parents’ comments to open-ended survey items are consistent with prior research suggesting that bereaved parents seek information, emotional support and an opportunity to provide feedback, as well as a physician communication style that is honest, complete and caring (9, 24–26). Parents’ comments reflected dissatisfaction when these communication goals were not achieved. Some parents were dissatisfied with the selection of health professionals attending the meeting although parental preferences regarding professional attendees were sought. Prior research suggests that in addition to the physician, parents often desire the presence of their child’s bedside nurse at follow-up meetings (9).

Physicians’ comments to open-ended survey items are consistent with prior research suggesting that physicians desire a systematic method for contacting parents and assistance with the logistics of arranging follow-up meetings (10, 27, 28). Physicians appreciated the structure that the CPCCRN framework provided for follow-up meetings although some physicians felt more structure would be helpful. The CPCCRN framework was intended to be flexible enough to be applicable to a wide variety of family circumstances (11). Additional training such as the inclusion of role playing may increase the comfort level of less experienced physicians preparing to use the framework. Physicians’ comments regarding benefits to them obtained by participating in follow-up meetings are consistent with those identified in our prior research and include reconnecting with families, gaining a deeper understanding of families’ perspectives, and achieving a sense of closure after a patient’s death (10, 29).

Limitations of this study include the large proportion of parents who either refused participation or could not be contacted. The low parent participation rate limits the generalizability of our findings; however follow-up meetings may still be important for parents who elect to attend. Characteristics of non-participating parents are unknown since their child’s medical records were reviewed for contact information and primary language only. Other limitations include the lack of validated instruments for evaluating adherence to and satisfaction with the CPCCRN framework. We did, however, utilize a consensus approach for video review and solicit feedback from multiple meeting participants to increase the validity and reliability of the findings. Strengths of this study include the geographic diversity of participants and sites, and the real-time collection of data by video recording.

CONCLUSIONS

The CPCCRN framework for physician-parent follow-up meetings after a child’s death in the PICU was developed and implemented based on the perspectives and experiences of bereaved parents, consistent with the tenets of patient- and family-centered care (30). Findings from this study demonstrate that follow-up meetings using this framework are feasible to conduct and perceived to be beneficial by parents, physicians and other health professionals. The framework provides a flexible structure that is easily learned and adhered to by critical care physicians. However, this study evaluates the feasibility of a single follow-up meeting. Future studies are needed to determine whether a single meeting affects bereaved parents’ short and long-term mental and physical health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The study was funded by cooperative agreements from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Department of Health and Human Services (U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD063108, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, U10HD050012 and U01HD049934).

Dr. Meert has received grant support and travel reimbursements from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Eggly, Berg, Wessel, Dalton, Clark, Dean and Newth have received funding from NIH. Dr. Shanley has received grant and travel support from NIH, has received payment for lectures from Advances in Neonatology, and receives royalties from Springer. Dr. Harrison has received grant and travel support from NIH and travel support from SCCM.

Footnotes

Reprints will not be ordered.

References

- 1.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Center to Advance Palliative Care; Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; Last Acts Partnership; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Executive Summary. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:611–627. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative Care for Children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truog RD, Cist AFM, Brackett SE, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2332–2348. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendrickson KC. Morbidity, mortality, and parental grief: a review of the literature on the relationship between the death of a child and the subsequent health of parents. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:109–119. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meert KL, Donaldson AE, Newth CJ, et al. Complicated grief and associated risk factors among parents following a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:1045–1051. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meert KL, Shear MK, Newth CJ, et al. Follow-up study of complicated grief among parents eighteen months after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:207–214. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. Parents’ perspectives regarding a physician-parent conference after their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2007;151:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meert KL, Eggly S, Berger J, et al. Physicians’ experiences and perspectives regarding follow-up meetings with parents after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e64–68. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e89c3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggly S, Meert KL, Berger J, et al. A framework for conducting follow-up meetings with parents after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:147–152. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e8b40c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willson DF, Dean JM, Meert KL, et al. Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network: Looking back and moving forward. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:1–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c01302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willson DF, Dean JM, Newth C, et al. Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:301–307. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000227106.66902.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health (US). Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network. [Accessed February 9, 2013];Request for Applications Number 08-HD-0025. 2008 Aug 22; Available from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HD-08-025.html.

- 15.National Institutes of Health (US) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Data Coordinating Center for the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network. [Accessed February 9, 2013 16.];Request for Applications Number 08-HD-0027. 2008 Aug 4; Available from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HD-08-027.html.

- 16.National Institutes of Health (US) Office of Extramural Research. [Accessed February 9, 2013];Certificate of Confidentiality Kiosk. Available from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/coc.

- 17.Charmaz K. Grounded theory. Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meert KL, Templin TN, Michelson KN, et al. The Bereaved Parent Needs Assessment: A new instrument to assess the needs of parents whose children died in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3050–3057. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825fe164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook P, White DK, Ross-Russell RI. Bereavement support following sudden and unexpected death: Guidelines for care. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:36–39. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHaffie HE, Laing IA, Lloyd DJ. Follow-up care of bereaved parents after treatment withdrawal from newborns. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F125–128. doi: 10.1136/fn.84.2.F125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein J, Peles-Borz A, Buchval I, et al. The bereavement visit in pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3705–3707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RF, Bylund CL. Communication skills training: Describing a new conceptual model. Acad Med. 2008;83:37–44. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c631e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: From everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1441–1460. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, et al. Parents’ perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298644.13882.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117:649–657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:14–19. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellison NM, Ptacek JT. Physician interactions with families and caregivers after a patient’s death: Current practices and proposed changes. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:49–55. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chau NG, Zimmermann C, Ma C, et al. Bereavement practices of physicians in oncology and palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:963–971. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggly S, Meert KL, Berger J, et al. Physicians’ conceptualization of “closure” as a benefit of physician-parent follow-up meetings after a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Palliat Care. 2012 (in press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meert KL, Clark J, Eggly S. Family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.02.011. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]