Abstract

Background

Recent debate about prostate specific antigen (PSA)-based testing for prostate cancer screening among older men has rarely considered the cost of screening.

Methods

We assembled a population-based cohort of male Medicare beneficiaries aged 66–99 years who had never been diagnosed with prostate cancer at the end of 2006 (n = 94,652) and followed them for three years to assess the cost of PSA screening and downstream procedures (biopsy, pathology, and hospitalization due to biopsy complications) at both the national and the hospital referral region (HRR) level.

Results

Approximately 51.2% of men received PSA screening tests during the three-year period, with 2.9% undergoing biopsy. The annual expenditures on prostate cancer screening by the national fee-for-service Medicare program were $447 million in 2009 US dollars. The mean annual screening cost at the HRR level ranged from $17 to $62 per beneficiary. Downstream biopsy-related procedures accounted for 72% of the overall screening costs and varied significantly across regions. Compared with men residing in HRRs that were in the lowest quartile for screening expenditures, men living in the highest HRR quartile were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer of any stage [incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.20, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07–1.35] and localized cancer (IRR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.15–1.47). The IRR for regional/metastasized cancer was also elevated although not statistically significant (IRR = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.81–2.11).

Conclusion

Medicare prostate cancer screening-related expenditures are substantial, vary considerably across regions, and are positively associated with rates of cancer diagnosis.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, prostate specific antigen, screening, stage, cost

Introduction

Since the widespread adoption of prostate specific antigen (PSA)-based screening, the lifetime risk of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer has nearly doubled, from 9% in 1985 to 16% in 2009, with approximately 89% of prostate cancers detected through screening.1 While PSA screening is expected to decrease the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer by diagnosing the disease at an earlier, treatable stage,2, 3 screening can harm individuals through false positive tests, overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

In May 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against the use of PSA-based screening for prostate cancer.4 This was a grade D recommendation that followed an earlier USPSTF recommendation in 2008, suggesting men aged ≥75 years should not undergo routine PSA-based screening.5 However, this 2008 recommendation had little impact on actual PSA screening use in the Medicare program.6 In April 2013, the American Urological Association released age-specific guideline statements that recommended shared decision-making for men age 55–69 years, and specifically did not recommend routine PSA screening in men ≥70 years.7 The American Cancer Society8 and the American Society of Clinical Oncology9 recommend that physicians discuss the risks and benefits of PSA screening with men who have at least a 10-year life expectancy.

Despite the growing concerns about routine PSA screening in the older population, little is known about the societal economic impact of screening. Notably, the USPSTF assessments did not take into account the cost of screening, and Medicare continues to reimburse for the test. In the context of clinical uncertainty about the benefits of screening and rising overall healthcare costs, it is important to understand the cost implications of PSA screening in the Medicare population. Although the PSA test itself is inexpensive, individuals with elevated PSA often require further workup such as biopsy. Furthermore, some beneficiaries require treatment for complications after prostate biopsy,10 resulting in additional costs to Medicare. The relative contributions of PSA tests and downstream procedures (biopsy, pathology, and hospitalization due to biopsy complications) to prostate cancer screening costs in the Medicare program represent a major knowledge gap.

The scope and impact of regional variation in prostate screening related costs represents a second major knowledge gap. A better understanding of how Medicare screening expenditures vary across regions could identify potential leverage points for intervention. The relation between regional prostate cancer screening costs and prostate cancer detection rates, in terms of the distribution of stage/risk of prostate cancer at diagnosis, would provide insights into whether there are population-level benefits of higher screening-related expenditures.

To address these knowledge gaps and to inform health policy interventions, we estimated Medicare prostate cancer screening expenditures (PSA and downstream procedures) for the national fee-for-service program and the subgroup of men ≥ 75 years. We then evaluated the association between regional-level spending on prostate cancer screening and the stage/risk classification of prostate cancer at diagnosis.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

Using the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of male Medicare beneficiaries who were free of prostate cancer as of December 31, 2006. The Yale Human Investigation Committee determined that this study did not constitute human subject research. The SEER registries account for approximately 28% of the US population.11, 12 The SEER-Medicare database links patient-level information on incident cancer diagnoses reported to the SEER registries with a master file of Medicare enrollment and claims for inpatient, outpatient, and physician services.13 It also includes a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the SEER regions, with administrative claims data and information on their cancer diagnoses, if any.

Individuals included in this study were part of Medicare’s 5% sample, did not have a diagnosis of prostate cancer on 12/31/2006, and fulfilled the following eligibility criteria: 1) aged 66–99 years on 1/1/2007, 2) had continuous fee-for-service Medicare coverage (Parts A and B) and were not enrolled in a health maintenance organizations from 1/1/2006 through the earliest of 12/31/2009, death, or diagnosis of prostate cancer, and 3) lived in a SEER region and had valid zip code information during 2007–2009. We excluded men who had no prostate cancer based on SEER records but who had Medicare claims with the International Classification of Disease, 9th Edition (ICD-9) diagnosis codes for prostate cancer (1.8%) or Medicare claims for prostatectomy or androgen deprivation therapy (0.06%) during 2006. All participants were assigned to Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare Project’s Health Referral Regions (HRRs)14 based on zip code of residence in 2007–2009. HRRs with less than 100 beneficiaries (n = 474) were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a final study sample of 94,652 beneficiaries.

Identification of Screening Procedures and Costs

We assessed the use of PSA screening and downstream procedures from 1/1/2007 through the earliest of 12/31/2009, death, or the last day of the month in which prostate cancer was diagnosed. PSA-based screening was determined using specific codes from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS): G0103, 84152, 84153, and 84154. Consistent with prior research,15 PSA tests conducted within 90 days of other PSA tests or within 180 days after a primary diagnosis of urinary obstruction, prostatitis, hematuria, other disorder of prostate, unexplained weight loss, or back pain were not considered prostate cancer screening. Biopsies were restricted to prostate biopsies that were done within 180 days after a PSA test. For each prostate biopsy, we counted the number of specimens jars containing tissue cores using HCPCS code 88305, as patients could have different numbers of specimens taken and Medicare payment is based on the number of specimens.16 Hospitalizations due to biopsy complications were defined as those that occurred within 30 days of prostate biopsies and had ICD-9 primary diagnosis codes consistent with complications.10

Costs were measured by Medicare payments, a good proxy for true economic cost,17 and adjusted to 2009 US dollars accounting for temporal and geographic variations.18, 19 We tallied costs for PSA screening and downstream procedures and calculated the average cost of screening per male Medicare beneficiary. To estimate total Medicare expenditures on prostate cancer screening in the US, we multiplied the mean per-beneficiary cost by the national estimate of male fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in different age ranges (66–74, 75–84, and 85–99 years).20

Statistical Analysis

For each HRR, we estimated the age-standardized screening rate, screening cost per beneficiary according to the age distribution of fee-for-service beneficiaries nationwide. Screening cost per beneficiary was the average expenditure on prostate cancer screening for all male Medicare beneficiaries, not just those who received screening. We classified the HRRs into quartiles of screening intensity based on screening costs per beneficiary and created three categories: the 1st quartile, the two middle quartiles, and the 4th quartile. Using multivariate Poisson regression models with an offset of log-transformed days until diagnosis of prostate cancer or end of follow-up, we assessed whether screening intensity was associated with the detection of prostate cancer overall and within four subgroups, which were classified based on PSA results, Gleason score and stage at the time of diagnosis21: (1) localized, low-risk; (2) localized, intermediate-risk; (3) localized, high-risk; and (4) non-localized (regional or metastasized). Age of beneficiary on 1/1/2007, race, comorbidities,22, 23 and median household income at the zip code level were included as covariates in the multivariate models. SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Approximately 50% of the 94,652 men in the study population were <75 years (mean age = 74 years), 84% were white, and close to half had at least one comorbid condition (Table 1). Among the study population, 51.2% of men had ≥1 PSA test during the 3-year follow-up, and 2.9% received prostate biopsy. Men aged 66–74 years were significantly more likely to undergo PSA testing (56.4% vs. 45.6% respectively, p<.001) and biopsy (3.7% vs. 2.1% respectively, p <.001) compared to men ≥75 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population (n = 94,652)

| Patient Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years on 1/1/2007 | ||

| 66–69 | 23,827 | 25.2 |

| 70–74 | 25,401 | 26.8 |

| 75–79 | 20,112 | 21.3 |

| 80–84 | 14,440 | 15.3 |

| 85–99 | 10,872 | 11.5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 79,824 | 84.3 |

| Black | 5,892 | 6.2 |

| Other | 8,936 | 9.4 |

| Median Household Income | ||

| <$33,000 | 18,968 | 20.0 |

| $33,000 – $39,999 | 15,790 | 16.7 |

| $40,000 – $49,999 | 19,757 | 20.9 |

| $50,000 – $62,999 | 17,577 | 18.6 |

| ≥$63,000 | 19,256 | 20.3 |

| Unknown | 3,304 | 3.5 |

| Comorbid Conditions | ||

| 0 | 48,347 | 51.1 |

| 1 to 2 | 32,260 | 34.1 |

| ≥ 3 | 14,045 | 14.8 |

| Stage and risk classification* | ||

| Localized- low-risk | 388 | 17.2 |

| Localized- intermediate-risk | 877 | 38.9 |

| Localized- high-risk | 468 | 20.7 |

| Regional/metastasized | 138 | 6.1 |

| Unknown | 386 | 17.1 |

Number of prostate cancer patients for state and risk classification = 2257.

Costs of PSA-based Prostate Cancer Screening

During 2007–2009, the average annual prostate cancer screening cost per beneficiary was $36 (Table 2). There was an inverse relation between age and screening cost (p<.001). Extrapolating the costs to the fee-for-service Medicare population nationwide, the annual cost to the Medicare fee-for-service program for prostate cancer screening was $447 million, including $145 million for men aged ≥75 years.

Table 2.

Average Annual Cost to Medicare for Prostate Cancer Screening during 2007–2009 (in 2009 US$)

| Age Group (years) |

Number of Fee-For-Service Medicare Beneficiaries |

PSA Rate (per 100) |

Annual Screening Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Cost Per Beneficiary |

Total Screening Cost* |

|||

| 66–74 | 7,000,356 | 32.6 | $43 | $301 M |

| 75–84 | 4,104,286 | 28.7 | $31 | $127 M |

| 85–99 | 1,314,851 | 17.9 | $14 | $18 M |

| Total | 12,419,493 | 29.8 | $36 | $447 M† |

Total screening cost to the Medicare fee-for-service program: M indicates million.

The total screening costs by age groups did not sum to total due to rounding.

Regional Variation in the Cost of Prostate Cancer Screening

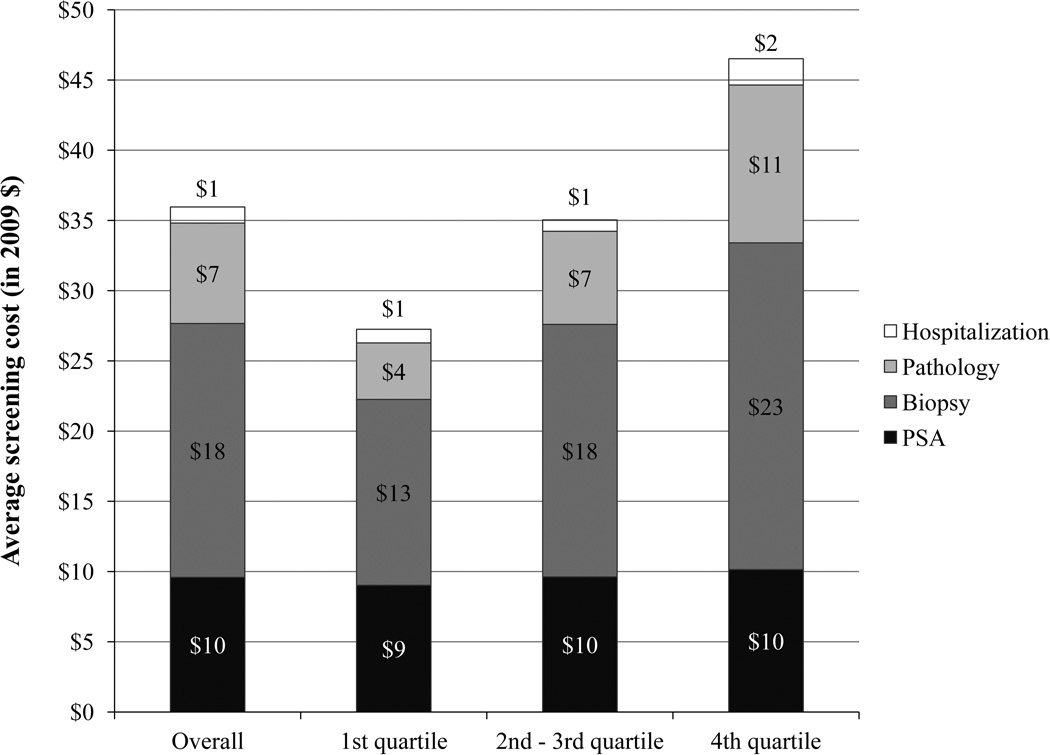

There was substantial regional variation in screening costs across the 94 HRRs. At the HRR level, the age-standardized average annual screening cost per beneficiary ranged from $17 to $62, with a median of $36 (interquartile range: $29–43). This regional variation in screening cost was largely driven by the cost of downstream procedures (Figure 1). PSA tests only accounted for 28% ($10 per beneficiary) of the overall screening cost, and the cost varied little across quartiles of screening expenditures ($9 per beneficiary in the 1st quartile, $10 per beneficiary in the 2nd –3rd and 4th quartiles). Conversely, biopsy-related costs (biopsy, pathology, and hospitalization due to biopsy complications) accounted for the majority (72%; $26 per beneficiary) of screening costs, with 50% ($18 per beneficiary) attributable to the biopsy procedure, 19% ($7 per beneficiary) to pathology fees, and 3% to hospitalization due to biopsy complications ($1 per beneficiary). The average annual biopsy costs per beneficiary at the HRR level were $13, $18, and $23 per beneficiary, respectively, in the lowest, middle, and highest quartiles for HRR-level screening expenditures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Medicare Expenditures for Specific Screening Procedures per Beneficiary According to Regional Prostate Cancer Screening Expenditures

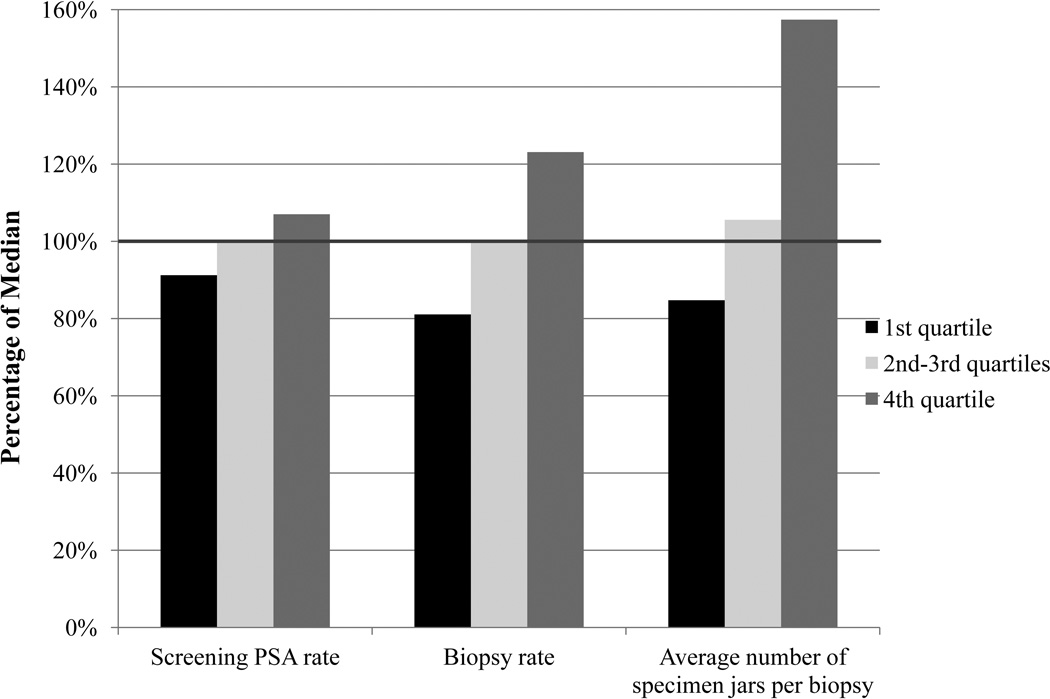

Procedure rates also correlated with regional expenditures. While the median HRR-level biopsy rate was 1.1%, the biopsy rate in the lowest quartile of expenditures (0.9% of men underwent biopsy) was 81.1% of the median biopsy rate, while the rate in the highest quartile was 123.1% of the median (p < .001) (Figure 2). Similarly, the number of specimens obtained for each biopsy ranged from 84.8% of the median rate in the lowest quartile to 157.4% in the highest quartile (p < .001). The screening PSA test rate varied little across quartiles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Screening PSA, Biopsy and Average Number of Specimens per Biopsy: Percent of Median Regional Utilization Rate According to Regional Prostate Cancer Screening Expenditures

Relation between Regional-level Screening Costs and Prostate Cancer Detection

Men residing in HRRs with higher screening costs per beneficiary were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer [incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.20 for highest vs. lowest quartiles, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07–1.35; Table 3]. When the analyses were stratified by age (66–74 years versus 75–99 years), men in both age groups were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer if they resided in higher-spending HRRs.

Table 3.

Regional-Level Prostate Cancer Incidence According to Regional Screening Expenditures

| HRR-level Screening Expenditures* |

All men | Age 66–74 years | Age 75–99 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Incidence (per 100,000) |

IRR† (95% CI) |

Annual Incidence (per 100,000) |

IRR† (95% CI) |

Annual Incidence (per 100,000) |

IRR† (95% CI) |

|

| Overall | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 761 | REF | 870 | REF | 655 | REF |

| 2nd–3rd quartiles | 874 | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) | 952 | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 723 | 1.05 (0.89–1.25) |

| 4th quartile | 1020 | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 1140 | 1.24 (1.06–1.44) | 942 | 1.31 (1.08–1.58) |

| Localized- low- risk | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 113 | REF | 155 | REF | 70 | REF |

| 2nd–3rd quartiles | 149 | 1.19 (0.91–1.56) | 209 | 1.25(0.91–1.71) | 71 | 0.93 (0.55–1.57) |

| 4th quartile | 202 | 1.52 (1.15–2.01) | 283 | 1.71(1.22–2.40) | 94 | 1.13 (0.64–2.01) |

| Localized- intermediate- risk | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 285 | REF | 344 | REF | 245 | REF |

| 2nd–3rd quartiles | 341 | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 387 | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 234 | 0.92 (0.69–1.22) |

| 4th quartile | 404 | 1.24 (1.03–1.49) | 475 | 1.27 (1.00–1.62) | 375 | 1.39 (1.03–1.88) |

| Localized- high- risk | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 167 | REF | 184 | REF | 125 | REF |

| 2nd–3rd quartiles | 171 | 0.99 (0.78–1.24) | 172 | 0.88 (0.65–1.20) | 183 | 1.41 (0.97–2.06) |

| 4th quartile | 215 | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) | 204 | 1.04 (0.73–1.47) | 233 | 1.70 (1.13–2.55) |

| Regional/metastasized | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 44 | REF | 29 | REF | 85 | REF |

| 2nd–3rd quartiles | 57 | 1.40 (0.91–2.14) | 43 | 1.57 (0.77–3.22) | 71 | 0.85 (0.52–1.41) |

| 4th quartile | 57 | 1.31 (0.81–2.11) | 46 | 1.66 (0.74–3.75) | 55 | 0.65 (0.35–1.24) |

HRR: Hospital referral region

IRR: incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval. Both were derived from multivariate Poisson models that adjusted for age group (66–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–99 years), race (white, black and other), median household income at the zip code level (in quintiles), and Elixhauser comorbidity score (0, 1–2, ≥3).

As for the stage of prostate cancer at diagnosis, men living in higher-spending areas were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with localized-low-risk (IRR = 1.52 for highest vs. lowest quartiles, 95% CI: 1.15–2.01) and localized-intermediate-risk (IRR = 1.24 for highest vs. lowest quartiles, 95% CI: 1.03–1.49) cancers (Table 3). The IRRs for localized-high-risk and regional/metastasized cancers were also elevated, although they did not reach statistical significance. In addition, among males aged 75 years or older, those resided in HRRs in the highest quartiles were more likely to be diagnosed with localized-high-risk prostate cancer than those in the lowest quartiles (IRR= 1.70, 95% CI: 1.13–2.55).

Discussion

We found that the Medicare fee-for-service program spent approximately $450 million annually on prostate cancer screening (PSA and downstream procedures). This amount is substantial and demonstrates that PSA-based screening is an important contributor to the overall cost of prostate cancer care. Particularly notable was the costs of screening among men ≥ 75 years, the group least likely to benefit from the practice: annual expenditures were $145 million for screening this population, or about one-third of total Medicare spending on prostate cancer screening.

Downstream procedures accounted for 72% of the overall cost of PSA-based prostate cancer screening and were the main driver of the regional variation in screening expenditure. The rate and cost of PSA tests did not vary much across regions. The considerable variation in the cost of screening across regions was largely attributable to different levels of prostate biopsy utilization and pathology costs, as reflected by variations in the biopsy rate and the average number of specimens per biopsy.

It is unclear which factors contributed to regional variation in the intensity of downstream workup (percent biopsied and number of specimens per biopsy), despite similar rates of PSA screening observed across the HRR groups. Urologists and radiation oncologists in different geographic regions of the US had differing opinions regarding the utility of prostate cancer screening.24 Our results show that the cost of prostate cancer screening is heavily influenced by how healthcare providers act upon PSA findings, not just whether a PSA test was ordered initially. Future work should explore these factors and their association with prostate cancer outcomes.

We found that men residing in regions with a higher spending on prostate cancer screening were more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer of any stage and with localized-low-risk and localized-intermediate-risk prostate cancer. This builds upon results from two randomized trials on PSA screening.25, 26 Both trials suggested that biopsies after elevated PSA values led to a high rate of detection of low-risk prostate cancers.25, 26 A recent report noted significant declines in the incidence of overall, early-stage, and late-stage prostate cancer in the SEER regions between 2007 and 2009 and suggested that the findings might be explained by lower screening rates after the 2008 USPSTF recommendation, although actual screening rates were not measured.27 In our data, the rates of localized-high-risk and regional/metastasized prostate cancer were also increased in regions with higher screening costs, although the findings did not reach statistical significance. Our observation should be interpreted cautiously, as the three-year follow-up period is too short to assess the long-term impact of screening on the incidence of localized-high-risk and regional/metastasized prostate cancer.

The economic impact of prostate cancer screening on Medicare expenditures goes far beyond the direct cost of PSA screening and downstream procedures. On a population level, a significant proportion of men with localized-low-risk prostate cancer have indolent disease and may not benefit from indiscriminate treatment.4 Since regions spending more on prostate cancer screening identified more prostate cancer patients and the majority of prostate cancer patients would then have received some type of treatments, rather than observation,28, 29 these regions likely also spent more on prostate cancer treatment. Future work should incorporate the impact of additional case detection in terms of treatment costs, as well as potential improvements in clinical outcomes.

Given the high percentage of screening cost that is attributable to biopsy, it would be important to test the utility of alternative, lower-cost approaches for downstream workup after detection of an elevated PSA. In addition to the use of PSA velocity, PSA density, artificial neural networks, models and nomograms,30 a variety of molecular biomarkers in blood, urine, and prostatic ejaculates have been studied.31–33 Hopefully, some of these approaches, if validated, can help inform clinicians’ and patients’ decision about biopsy.

This study has many strengths, including a large, population-based cohort of Medicare beneficiaries from different geographic areas, the assessment of the cost of downstream procedures in addition to PSA screening, the incorporation of stage and risk classification of prostate cancer at diagnosis, and the ability to adjust for covariates that may affect the rate of screening (e.g., age, race, comorbidity, and neighborhood socioeconomic status).

The study also has some limitations. Since we relied on Medicare claims to evaluate prostate cancer screening, our study population was restricted to those aged 66 years or older. We used an established algorithm to define “screening PSA” and excluded men with various conditions who might have received PSA test as part of a clinical workup (instead of screening). However, it is possible that some of the PSA tests included in our evaluation were not intended for screening. In addition, we focused on the cost of prostate cancer screening and did not explore the cost of not screening (e.g., potentially more patients with advanced diseases). As it may take many years for metastasis to develop after the initial development of prostate cancer, longitudinal studies with a long duration of follow-up are needed to assess whether screening leads to lower rates of metastatic disease and their cost implications.

In conclusion, in an era with widespread PSA screening for prostate cancer, the practice imposed a substantial economic burden on Medicare, through the cost of PSA tests, downstream procedures and subsequent treatment. The substantial regional variation in screening expenditures appears to be driven largely by use of biopsy. Future studies need to assess the cost effectiveness of PSA-based screening among older men, and identify subgroups of individuals who may benefit the most from screening and treatment.34

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Stacy Loeb for sharing codes for the identification of hospitalizations due to complications of prostate biopsy.

The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute (NCI)'s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of the SEER-Medicare data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Drs. Ross and Gross receive support from Medtronic, Inc. to develop and implement methods of clinical trial data sharing and patient-level meta-analyses. Dr. Ross is supported by the National Institute of Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program, by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures, and by the Pew Charitable Trusts to examine regulatory issues at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Yu is supported by CTSA Grant Number KL2 RR024138 from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. Dr. Makarov is a VA HSR&D Career Development awardee at the Manhattan VA. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding: This study was supported by two grants from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA016359 and 5R01 CA149045).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of interest: Drs. Ross, Gold, and Gross are members of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health, Inc.

References

- 1.Hoffman RM, Stone SN, Espey D, Potosky AL. Differences between men with screening-detected versus clinically diagnosed prostate cancers in the USA. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciezki JP, Reddy CA, Kupelian PA, Klein EA. Effect of prostate-specific antigen screening on metastatic disease burden 10 years after diagnosis. Urology. 2012;80:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scosyrev E, Wu G, Mohile S, Messing EM. Prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer and the risk of overt metastatic disease at presentation: analysis of trends over time. Cancer. 2012;118:5768–5776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer VA. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.USPSTF. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:185–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross JS, Wang R, Long JB, Gross CP, Ma X. Impact of the 2008 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation to Discontinue Prostate Cancer Screening Among Male Medicare Beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2012:1–3. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Oliver TK, Vickers A, et al. Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen testing: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3020–3025. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, Ricker W, Schaeffer EM. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 186:1830–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ries L, Kosary C, Hankey B, Miller B, Clegg L, Dewards B, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller B, Ries L, Hankey B, editors. Institute NC. Cancer Statistics Review 1973–89. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 1992. No. 92–2789. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potosky A, Riley G, Lubitz J, Mentnech R, Kessler L. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor related database. Medical Care. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dartmouth Medical School. The Dartmouth atlas of health care. Chicago, Ill: American Hospital Publishing; 1996. Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter LC, Bertenthal D, Lindquist K, Konety BR. PSA screening among elderly men with limited life expectancies. Jama. 2006;296:2336–2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell JM. Urologists' self-referral for pathology of biopsy specimens linked to increased use and lower prostate cancer detection. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:741–749. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-104–IV-117. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren JL, Brown ML, Fay MP, Schussler N, Potosky AL, Riley GF. Costs of treatment for elderly women with early-stage breast cancer in fee-for-service settings. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:307–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu-Yao G, Albertsen PC, Stanford JL, Stukel TA, Walker-Corkery ES, Barry MJ. Natural experiment examining impact of aggressive screening and treatment on prostate cancer mortality in two fixed cohorts from Seattle area and Connecticut. BMJ. 2002;325:740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao YH, Demissie K, Shih W, et al. Contemporary risk profile of prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1280–1283. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNaughton Collins M, Barry MJ, Zietman A, et al. United States radiation oncologists' and urologists' opinions about screening and treatment of prostate cancer vary by region. Urology. 2002;60:628–633. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01832-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard DH. Declines in prostate cancer incidence after changes in screening recommendations. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1267–1268. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Blackford AL, et al. How does initial treatment choice affect short-term and long-term costs for clinically localized prostate cancer? Cancer. 2010;116:5391–5399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehrborn CG, Albertsen P, Stokes ME, Black L, Benedict A. First-year costs of treating prostate cancer: estimates from SEER-Medicare data. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:355–360. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokoll LJ, Sanda MG, Feng Z, et al. A prospective, multicenter, National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network study of [−2]proPSA: improving prostate cancer detection and correlating with cancer aggressiveness. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1193–1200. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhavsar T, McCue P, Birbe R. Molecular diagnosis of prostate cancer: are we up to age? Semin Oncol. 2013;40:259–275. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurel B, Iwata T, Koh CM, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM. Molecular alterations in prostate cancer as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:319–331. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31818a5c19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salagierski M, Schalken JA. Molecular diagnosis of prostate cancer: PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion. J Urol. 2012;187:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotwal AA, Mohile SG, Dale W. Remaining Life Expectancy Measurement and PSA Screening of Older Men. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]