Abstract

The structure and bonding of the gold-subhalide compounds Au144Cl60[z] are related to those of the ubiquitous thiolated gold clusters, or Faradaurates, by iso-electronic substitution of thiolate by chloride. Exact I-symmetry holds for the [z] = [2+,4+] charge-states, in accordance with new ESI-MS measurements and the predicted electron shell filling. The High symmetry facilitates analysis of the global structure as well as the bonding network, with some striking results.

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of thiolates on noble-metal electrodes and nanostructures are regarded as prime examples of chemical nanotechnology,1,2 based upon the bridging coordination of the thiolate-sulfur head-group,3 as established only recently by rigorous structure determination.4,5 Remaining challenges concern the complexity of the electronic structure and bonding that underlie the observed phases and their properties.

Here we consider the structure (Figure 1) of the large gold-subchloride Au144Cl60[2+/4+] cluster, as an isoelectronic analog6 of the ubiquitous thiolated gold clusters Au144(SR)60[z], also known as Faradaurates.7,8 This construction is also of interest for its exceptionally high symmetry (I) and compactness [see below].

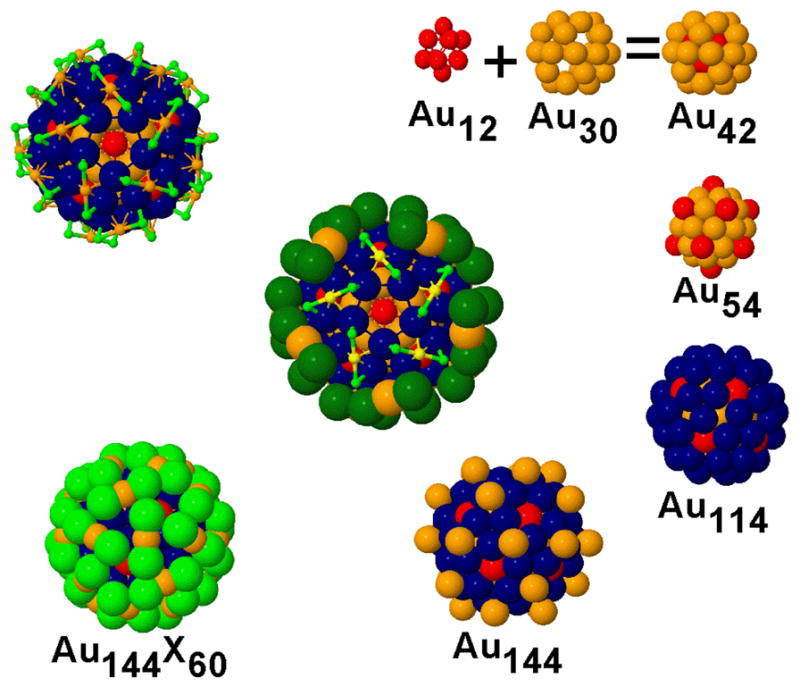

Figure 1.

Structure of the I-Au144X60[z] compound, clock-wise from top right: Assembly of the 42-Au structure from the hollow inner 12-Au shell (red) and the inner 30-Au shell (orange). Adding the outer 12-Au (also red) yields the ‘inner core’ comprising 54-Au atoms. The ‘grand core’ view Au144 highlights the shell of 60-Au sites (blue) in relation to the outer 12-Au sites. The Au144 substructure (bottom center) comprises 30-Au sites (also orange). The 60-X halide sites (green) complete the assembly (lower left) and define the topography. The view at top left, along a C5 symmetry axis, exposes the symmetric arrangement of ‘staple-motif’ surface units. At centre, the cutaway view of the spacefilling C5 perspective highlights five of the staple units (in small light green for Cl and small yellow for Au). Color code: 60-X = green; outer 30-Au = small orange; 60 Au = blue; groups of 12 Au = red; inner 30-Au = orange.

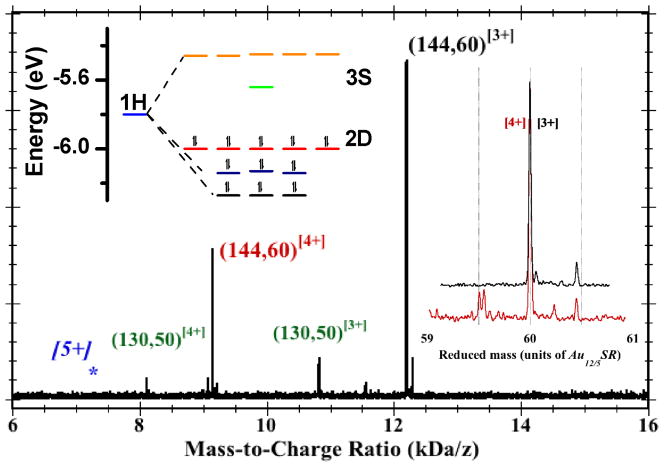

Figure 2 provides evidence of a limiting charge-state [4+], present in the solution-phase of a sample (prepared using R = −CH2CH2Ph) beyond that which could be obtained in the pioneering ESI-MS measurements.9–12

Figure 2.

Mass spectrum of a sample of purified Au144(peth)60 clusters, obtained by the electrospray-ionization (ESI) time-of-flight (ToF) method. [See SI Section.] The labelled peaks indicate the assignments to the [3+] (black) and [4+] (red) charge-states. The blue [5+] and asterisk indicate the expected location of the missing [5+] peak near 7.2 kDa/e, and the green-labeled peaks designate a residual impurity (or byproduct) also known from earlier research. Right Inset: Expanded regions of the [4+] and [3+] peaks, plotted versus the mass (rather than mass-to-charge-ratio), in units of the 60-fold unit (~ 0.610 kDa) of Au12/5(peth)1, so that the principal peaks are overlaid at reduced-mass 60. The position and width (FWHM ~ 12 Da) of these peaks are consistent with the natural isotope abundance of 13C. Minor satellite peaks toward higher masses are assigned to Cs+-adduct formation (each Cs-atom is 0.133-kDa, or 0.218 on the reduced-mass scale). The main satellite peak toward lower mass is attributed to organic disulfide (RS-SR) loss (0.274-kDa, or 0.448). Left Inset: Energy-level diagram for the frontier orbitals of Au144Cl60[4+], (HOMOs 2D10, LUMO S0) but generic to the I-Au144(SR)60[z+] systems. Seventeen (17) orbitals are classified according to united-atom (or ‘superatom’)27 representations {1H, 2D, 3S}, where {S,P,D,F,G,H, …} denote respective total angular momenta L = {0,1,2,3,4,5, …} with (2L+1)-fold orbital degeneracy. The electronic 1H-shell splits under an icosahedral field into groups of (3,3,5) each, cf. Ih-C60 or -C80 clusters. Electronic closed-shell configurations are expected for charge-states [4+] (depicted), [2+], and [8−]. The neutral state is open shell and subject to Jahn-Teller instability (deformation); see SI for details.

The Fig. 2 Inset presents an energy-level diagram, characteristic of I-Au144Cl60[z] as well as Au144(SR)60[z],13 depicting the filling of the frontier orbitals for each state.

The structure of I-Au144Cl60 was obtained either by: (i) Isoelectronic substitution6 of chloride ions (Cl−) for hydrogen-sulfide (HS−) or methane-thiolate (CH3S−) anions, starting from the models13 motivated by ref. 14; or (ii) De novo construction from the crystal structure of the icosahedral compound Pd145(CO)60(PR3)30.15

In both cases, the same structure obtains via energy minimization based upon density functional theory (DFT) electronic structure calculations. The I-Au144Cl60[z] structures are then re-optimized for each charge-state [z] considered. The methods were tested by repeating the recent analysis of Th-Au25Cl18[1−] by Jiang and Walter.6

We assessed the cohesion of this structure by the following chemical equation, representing decomposition of I-Au144X60 into ‘super-stable’ closed-shell I-Au72 and [Au(I)X]4 ‘rings’.6,16

The energy required is +68 eV, which is +110 kJ/mol-Cl (+45 kJ/mol-Au). Thus the structure is highly cohesive.

The optimized structure holds chiral-icosahedral (I) symmetry, at a tolerance of 0.13 Å in the neutral [z=0] state, improving to 0.03 Å in both [2+] and [4+] states. These reflect the closed electronic shells, 3S2 and 2D10, respectively, depicted in Fig. 2 (inset). In the latter [4+] state, the HOMO-LUMO gap, separating the filled 2D orbitals from the empty 3S and the unoccupied portion of the 1H set, approaches 0.5 eV (see Figure S6 for other charge states). The enhanced symmetry is also reflected in the restored degeneracy of the frontier orbitals vs. refs. 13 or 17 (Tables S1,S2).

The neutral [z=0] form is destabilized by the partial (1/5) occupancy of a 5-fold degenerate level, indicating a Jahn-Teller mechanism, as suggested by Tofanelli and Ackerson to explain the charge-dependent thermal stability.18 Spin-polarized calculations of the optimized neutral confirm a paired (spin-zero) rather than aligned (spin-unity) electronic configuration. Of course, it is already well established how the Jahn-Teller mechanism operates in icosahedral (Ih) symmetry systems such as the fullerides (C60 anions).19

Crucially, the finding that electronic closed-shell forms of I-Au144Cl60[z], hold the full I-symmetry agrees with the recent demonstration of the 60-fold equivalence of the thiolate ligands by NMR spectroscopy.14

The halide-for-thiolate substitution6 facilitates the description by eliminating both the conformationally variable R-groups and the pyramidal inversion mode of the bridging thiolate S-atom.3

The structure comprises 2o4 atomic sites, distributed over two sets each of {12,30,60}-fold equivalent sites.

Proceeding from the center outward, one finds concentric shells of {12, 30, 12; 60, 30, 60X} sites, where X denotes the shell of halide (X−) sites, as color-coded in Figure 1.

Because the respective shells must be aligned to preserve overall I-symmetry, eight (8) parameters suffice to specify completely the location of all 204 atoms.20–22 A convenient choice includes the radii of the six shells along with two angles indicating the degree of rotation of the two 60-fold shells away from an Ih-symmetric configuration, i.e. these angles would vanish if Ih-symmetry held. For the optimized Au144Cl60[2+] compound, the six radial distances are {2.68, 4.89, 5.74, 7.02, 8.88 and 9.31 Å}, and the angles measure ~ 6 and ~17 degrees, as compared to the maximum rotation (~ 19 degrees).20–21

These values establish the extreme compactness of the optimized I-symmetry structure, based on the established ‘staple-motif’ units, with attractive alternatives, e.g. a Mackay-icosahedral Ih-(147,60) structure of metallic radius > 10.0 Å, wherein the 60Au sub-shell assumes an open truncated-icosahedron (buckyball) form and the 60X bridging ligands are exterior, i.e. non-stapling.

The layer-by-layer (concentric-shell) construction in Fig. 1 gives a global picture of the structure and bonding, explicable largely via ‘atom-packing’ considerations.

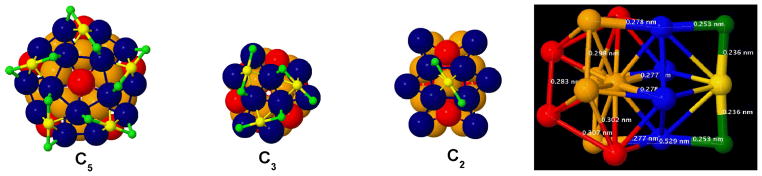

The I-symmetry also simplifies the analysis of the local bonding characteristics: The three sections in Fig. 3 are selected as orthogonal projections,20 presenting distinct views along one each from the many equivalent C2, C3, or C5 axes.

Figure 3.

Sections of the Structure of I-Au144Cl60[2+]. The repeated surface-structure and bonding of the I-Au144Cl60 structure are illustrated by views along one each of the {6 C5, 10 C3, 30 C2} symmetry axes, corresponding to orthogonal projections of the I-symmetry polyhedron (34.5*).20 The colour scheme is preserved from Fig. 1. Left: The C5-projection, cf. Fig. 1, shows the mutual orientations among five staple-motif units, revealing a chiral ‘Texas-Star‘ pattern. Center-Left: The C3-projection centers on a hole, and shows the mutual orientations of three staple-motif units. Center-Right: The C2-projection shows an inward centered view of a single staple-motif unit, i.e. the collinear X-Au-X (green-yellow-green) anchored by two surface Au atoms (navy-blue). To discern the two rotation angles, note that the blue rhombus displaces slightly clockwise with respect to the orange sub-structure while the staple vector (X-Au-X) rotates much further.28 Right: Side view of a C2-Section marked to indicate the special surface bonding and internal packing arrangements. Proceeding left to right (inside-outward), the sites are from the inner 12-Au (red pair), the inner 30-Au (orange quintet), the outer 12-Au (red pair), the 60-Au (blue quartet), and the 60-X sites (green pair) plus the outer 30-Au (yellow singlet). The collinear green-blue-orange alignment is evident at top and bottom, and forms the bold radial elements in Fig. 4.

From the C2-projection, which features one complete staple-motif unit, the meaning of the two angles, one for each of the 60Au and the 60X shells, becomes apparent: The first angle transforms the blue squares into diamonds, while the second provides additional rotation of the green-yellow X-Au-X vectors needed to distribute uniformly the (nonbonding) X-sites.

From the C3, or C5 projections, one perceives how these displacements optimize the spatial distribution of the X-sites. The X-X distances are ~ 4.7 Å (across a C2 axis, via an Au ‘adatom’ site), ~ 5.0 Å (around a C3 axis), and ~ 4.0 Å (around a C5 axis), as compared to the atomic dimension, ~ 3.6 Å (chloride ionic diameter).

Figure 4(a) presents selected details of the local bonding arrangement. One familiar aspect4 of the staple motif is the shorter (2.36 Å), stronger X-Au bonding parallel (tangential) to the cluster surface, as compared to the longer X-Au bonds (2.53 Å) perpendicular (radially directed). These are the shortest bonds in the entire structure.

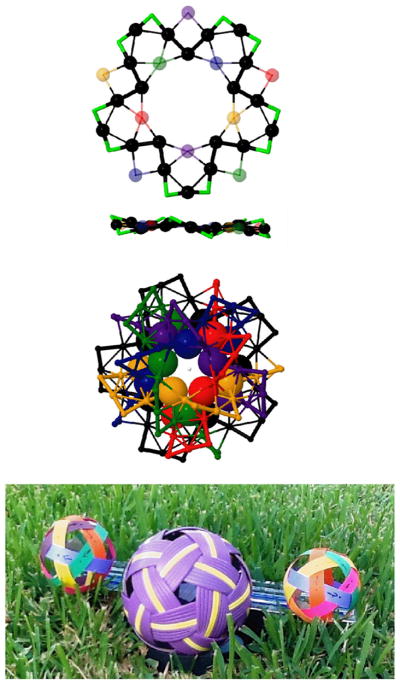

Figure 4.

Selected Characteristics of I-Au144Cl60[2+]. (Top) A single strand (black) is identified by continuation of the radial elements identified in Fig. 3 (right). The black circles and green elbows constitute a single closed loop. Thick connecting lines designate the short bonds; the five (5) sets of distinctly coloured spheres mark under- and over-crossings of the other five strands. In side-view, the structure is essentially flat, incorporating the two coplanar regular decagons from the 30-Au shells (Fig. 1, in orange), the nearly 10 nearly coplanar sites from the 60-Au shell (blue in Fig. 1), and the zig-zag pattern of the 60-X sites (10 lime-green elbows) (Centre) Hemisphere view of all six (6) coloured strands, obtained by elaboration from the single strand. All but 24 sites (the two 12-Au shells) of the 204 sites are incorporated into the weave structure. (Bottom) Photograph of a standard woven kickball (Sepak Tetraw in the Thai language) on Texas Grass. It displays the same 6-strand network topology, including chirality, as that identified herein for the I-Au144X60 structure, thus serving an aide memorandum to the entire structure.

An unexpected aspect is revealed by continuation inward along these radial X-Au directions, which point toward Au-atoms of the inner 30Au shell (orange). In fact, the 60 Au-Au equivalent contacts identified in this way are the shortest inter-Au distances (~2.77 Å) in the structure, including the compact ‘inner core’, cf. Fig. S2.

The bonding network identified by considering only these shortest X-Au and Au-Au bonds is presented in the Fig. 4(b,c), which forms a segmented Great Circle comprising five (5) staple-motif units. This provides a convenient way to visualize the entire structure (minus two sets of 12 Au atoms). It consists of six (6) equivalent ‘strands’ interwoven in the manner of the Thai woven kickball (Sepak Tatraw), depicted in the Inset, Fig. 4(d).

The six-strand weave incorporates 180 of the 204 sites (Fig. S7).

The optimized structure in [2+] and [4+] charge states is predicted to hold the exact I-symmetry, which greatly simplifies the analysis of the structure and bonding.

Both the compactness and the estimated cohesion with respect to prior stable units support the mechanical stability of the compound, regardless of the electronic configuration.

The gold-subhalide compound may appear an unlikely candidate for chemical synthesis, given likely poor solubility in conventional solvents,24 yet there exist many reports of so-called ‘ligand-free’ gold clusters, of dimension similar to this one (~ 1.8 nm diameter), obtained in complex media (ionic liquids, dendrimers etc.) incorporating halide or pseudo-halide agents.25,26

Conclusions

In summary, we have considered the crucial structural characteristics underlying the ubiquity of the Au144(SR)60 compounds (Faradaurates), employing isoelectronic substitution of thiolate anion by halide (chloride).

This allows one to establish theoretically the closed-shell electronic character of the [2+,4+]-charge-states, in agreement with new results from electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

One should therefore extend the isoelectronic method to other halides and charge-states, at least to [8-], that may be appropriate to those conditions, and to search for gold-subhalides Au144X60[z] in electrospray ionization mass spectra measured on complex-media samples.

Although no Au144(SR)60[z] compound has yielded to total structure determination, it is encouraging that the established structure4 of Au102(SR)44[0] exhibits similar stereochemistry in its polar regions (comprising 30 of 44 thiolate groups) that may be explicable in terms of the simpler structure of the isoelectronic analog Au144X60.29

Finally, we stress the conceptual and theoretical advantages to employing the high I-symmetry whenever practicable: The large order of this group, O(60), implies a repeat unit of merely Au12/5X1 (3 2/5 atoms), fewer even than the Au2X3/2 (3 1/2 atoms) of the most studied small cluster, Th-Au24X18 cluster, a group of O(12). This symmetry advantage is maintained, when replacing halogen (X) by thiolate (-SR) groups. The enormous reduction in complexity may mean that an understanding of the structure, bonding, and electronic properties of ligand-protected noble-metal clusters, in the crucial size-range where the characteristically ‘metallic’ properties emerge, may not be so distant, after all.29

All details of experimental & computational methods and results are in the Supporting Information Section.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Mr. Nabraj Bhattarai who prepared and characterized (as described in ref. 13) the sample used in the ESI-MS measurements, and also the following funding sources: National Center for Research Resources (5 G12RR013646-12) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (G12MD007591) from the National Institutes of Health, and National Science Fundation (NSF) for support with grants DMR-1103730, “Alloys at the Nanoscale: The Case of Nanoparticles Second Phase and PREM: NSF PREM Grant # DMR 0934218; “Oxide and Metal Nanoparticles-The Interface Between Life Sciences and Physical Sciences”.

All calculations were done in the Texas Advance Computing Center and by using resources of the Computational Biology Initiative.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental Methods and Materials; Theoretical method and Tables and graphs including the structure analysis of various Au144R60[z] clusters. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Love JC, Estroff LA, Kriebel JK, Nuzzo RG, Whitesides G. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1103–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr0300789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniel MC, Astruc D. Chem Rev. 2004;104:293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dance IG. Polyhedron. 1986;5:1037–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadzinsky PD, Calero G, Ackerson CJ, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Science. 2007;318:430–433. doi: 10.1126/science.1148624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maksymovych P, Voznyy O, Dougherty DB, Sorescu DC, Yates JT., Jr Prog Surf Sci. 2010;85:206–240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang DE, Walter M. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4234–4239. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dass A. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19259–19261. doi: 10.1021/ja207992r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faraday Michael. Philos Trans R Soc London. 1857;147:145–180. [Footnote] G. Schatz (Northwestern Univ.) has proposed similarly that Faraday Band may denote the localized surface-plasmon resonance that emerges in protected larger clusters of gold (and other metals). Quotation repeated with permission of Prof. George Schatz. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaki NK, Negishi Y, Tsunoyama H, Shichibu Y, Tsukuda T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8608–8610. doi: 10.1021/ja8005379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian H, Jin R. Nano Lett. 2009;9:4083–4087. doi: 10.1021/nl902300y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fields-Zinna CA, Sardar R, Beasley CA, Murray RW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16266–16271. doi: 10.1021/ja906976w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumara C, Dass A. Nanoscale. 2011;3:3064–3067. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10429b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahena D, Bhattarai N, Santiago U, Tlahuice A, Ponce A, Bach SBH, Yoon B, Whetten RL, Landman U, Jose-Yacamán M. J Phys Chem Lett. 2013;4:975–981. doi: 10.1021/jz400111d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong OA, Heinecke CL, Simone AR, Whetten RL, Ackerson CJ. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4099–4102. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30259d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran NT, Powell DR, Dahl LF. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:4121–4125. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4121::aid-anie4121>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karttunen AJ, Linnolahti M, Pakkanen TA, Pyykkö P. Chem Commun. 2008:465–467. doi: 10.1039/b715478j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Acevedo O, Akola J, Whetten RL, Grönbeck H, Häkkinen H. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:5035–5038. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tofanelli MA, Ackerson CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16937–16940. doi: 10.1021/ja3072644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chancey CC, O’Brien MC, editors. The Jahn-Teller Effect in C60 and Other Icosahedral Complexes. Chapters 2 & 3 Princeton University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams R. The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin TP. Physics Reports. 1996;273:199–241. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackay AL. Acta Cryst. 1962;15:916–918. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama Y. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. 2012;79:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartig J, Stösser A, Hauser P, Schnöckel HG. Angew Chem Int Eng. 2007;46:1658. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yancey DF, Chill ST, Zhang L, Frenkel AI, Henkelman G, Crooks RM. Chemical Science. 2013;4:2912–2921. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Held A, Moseler M, Walter M. Phys Rev B. 2013;87:045411. and reference therein. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter M, Akola J, Lopez-Acevedo O, Jadzinsky PD, Calero G, Ackerson CJ, Whetten RL, Grönbeck H, Häkkinen H. Proc Nat Ac Sci USA. 2008;105:9157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bochicchio D, Ferrando R. Nano Lett. 2010;10:4211–4216. doi: 10.1021/nl102588p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cademartiri L, Kitaev V. Nanoscale. 2011;3:3435–3446. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10365b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.