Abstract

Metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma (MSC) of the breast is usually triple receptor (ER, PR, and HER2) negative and is not currently recognized as being more aggressive than other triple receptor-negative breast cancers. We reviewed archival tissue sections from surgical resection specimens of 47 patients with MSC of the breast and evaluated the association between various clinicopathologic features and patient survival. We also evaluated the clinical outcome of MSC patients compared to a control group of patients with triple receptor-negative invasive breast carcinoma matched for patient age, clinical stage, tumor grade, treatment with chemotherapy, and treatment with radiation therapy. Factors independently associated with decreased disease-free survival among patients with stage I–III MSC of the breast were patient age >50 years (P = 0.029) and the presence of nodal macrometastases (P = 0.003). In early-stage (stage I–II) MSC, decreased disease-free survival was observed for patients with a sarcomatoid component comprising ≥95% of the tumor (P = 0.032), but tumor size was the only independent adverse prognostic factor in early-stage patients (P = 0.043). Compared to a control group of triple receptor-negative patients, patients with stage I–III MSC had decreased disease-free survival (two-sided log rank, P= 0.018). Five-year disease-free survival was 44 ± % versus 74 ± 7% for patients with MSC versus triple receptor-negative breast cancer, respectively. We conclude that MSC of the breast appears more aggressive than other triple receptor-negative breast cancers.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Metaplastic carcinoma, Sarcomatoid, Triple-negative, Survival

Introduction

Metaplastic carcinomas comprise a small but histologically diverse group of invasive breast cancers that share an unusual morphologic characteristic: part or all of the tumor cells appear to have undergone transformation to a non-glandular epithelial or mesenchymal cell type [1–6]. The histologic appearance of metaplastic carcinomas of the breast can vary greatly. As a group they tend to be triple receptor (ER, PR, and HER2) negative, but the nonglandular component can range from only focal squamous differentiation, which appears to be clinically insignificant, to diffuse mesenchymal differentiation. The mesenchymal component can be cytologically bland and clinically indolent or resemble a sarcoma and behave aggressively. In spite of this diversity, metaplastic carcinomas are often lumped together and referred to as if they were a single distinct subtype.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines for invasive breast cancer state that metaplastic breast carcinomas should be treated like other invasive breast carcinomas. The recommendation is based on the assumption that the metaplastic component does not alter prognosis [7]. There are, indeed, conflicting outcome data for metaplastic carcinoma in the literature, but the conflicting data are likely a result of the heterogeneity of tumors included in many studies. A number of reports on specific subtypes of metaplastic carcinoma, in contrast, suggest that the clinical behavior of certain metaplastic carcinoma subtypes is distinct from typical invasive breast carcinomas [8–15].

In this study, we evaluated the clinical outcome of patients with metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma (MSC) of the breast and analyzed the association between clinical outcome and various clinicopathologic features of MSC, including the percentage of sarcomatoid component within the primary tumor. As most cases of MSC are triple receptor negative, we also compared the outcome of MSC patients to a control group of triple receptor-negative breast cancer patients matched for patient age, clinical stage, tumor grade, treatment with chemotherapy, and treatment with radiation therapy.

Methods

MSC patients

Patients with MSC of the breast diagnosed at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) with definitive surgery performed from 1986 to 2008 were identified from the surgical pathology files in the Department of Pathology by conducting a database search using SNOMED codes for the terms sarcomatoid carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and metaplastic carcinoma and by performing a text search of diagnoses for breast specimens using the terms metaplastic, sarcomatoid, and carcinosarcoma. The tissue slides from each primary tumor were retrieved from the MDACC pathology archives in accordance with an IRB-approved protocol for this study. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients with tumors having at least focal intermediate- to high-grade sarcomatoid morphology and an obvious invasive carcinomatous component; and (2) patients with purely sarcomatous tumors that expressed keratin by immunohistochemistry and/or had associated ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Patients were excluded if representative slides were not available for review from the primary tumor. As part of the study objective was to compare outcomes of patients with mixed versus pure sarcomatid morphology, patients with pure (≥95%) sarcomatoid morphology in the surgical specimen were excluded if they received primary (preoperative) chemotherapy, as such patients might have had a significant carcinomatous component before chemotherapy. Patients with low-grade fibromatosis-like metaplastic tumors and other metaplastic tumors with a low-grade spindle cell component were also excluded. The clinicopathologic features of a subset of these patients were reported previously [9].

Clinical information was obtained from clinical databases in the Department of Surgical Oncology and Department of Breast Medical Oncology at MDACC and supplemented with information from the hospital records and pathology reports. Clinicopathologic features evaluated for each case included the age of the patient, clinical stage, tumor size, the percentage of sarcomatoid component comprising each tumor, the histologic type of sarcomatoid differentiation, the grade of the sarcomatoid component, the grade of the carcinomatous component, the presence of lymphovascular invasion, the extent of axillary lymph node involvement, hormone receptor and HER2 status, treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and clinical outcome.

Triple receptor-negative patients

A control group of patients with triple receptor-negative invasive ductal carcinoma was selected from a clinical database in the Department of Breast Medical Oncology at MDACC. The control patients were matched as closely as possible to stage I–III MSC patients according to patient age, clinical stage, tumor grade, treatment with chemotherapy, and treatment with radiation therapy. For patient age, 28 patients were matched within 1 year, nine patients within 2 years, two patients within 3 years, and one patient within 4 years. For some patients, matches were not available for grade or stage. In these cases, the next higher grade or stage was selected for the control patient so that the match would not favor a worse outcome for MSC. Six patients in the control group had high-grade tumors compared to intermediate-grade tumors in the corresponding MSC patients, one control patient was stage IIIB instead of IIIA, and one control patient was stage IIIC instead of IIIB. One patient in the control group was treated more aggressively with chemotherapy and radiation compared to radiation only in the corresponding MSC patient; in subsequent follow-up analysis, neither the control patient nor the corresponding MSC patient experienced tumor recurrence, and so this treatment difference did not favor a worse outcome for MSC. The triple-negative control patients had definitive surgery from 1997 to 2006.

Statistical analyses

Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier product limit method. The two-sided log-rank test was used to test the association between particular clinicopathologic features and patient survival. Disease-free survival was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the date of local or regional disease recurrence, distant metastasis, or death from disease or to the last follow-up date. Overall survival was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the date of death from any cause or to the last follow-up date. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. All statistical analyses were carried out using SSPS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Forty-seven patients with MSC of the breast met the inclusion criteria for this study. The clinicopathologic features of these patients are provided in Table 1. All of the patients were women. The median patient age was 59 years (range, 32–80 years). The median tumor size was 3.3 cm (range, 1.5–12 cm). Twenty-six patients (55%) had early-stage (stage I–II) disease. For patients with known receptor status, 34 of 37 (92%) were ER negative, 32 of 36 (89%) were PR negative, and 22 of 22 (100%) were HER2 negative.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of patients with metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the breast

| Clinicopathologic feature | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient age | |

| ≤50 years | 12 (26) |

| >50 years | 35 (74) |

| Clinical stage | |

| I | 6 (13) |

| IIA | 19 (40) |

| IIB | 1 (2) |

| IIIA | 7 (15) |

| IIIB | 6 (13) |

| IIIC | 2 (4) |

| IV | 2 (4) |

| Unknown | 4 (9) |

| Tumor size | |

| ≤2 cm | 4 (9) |

| >2 cm and ≤5 cm | 20 (43) |

| >5 cm | 11 (23) |

| Unknown | 12 (26) |

| Axillary lymph node status | |

| Negative | 26 (55) |

| Isolated tumor cells | 1 (2) |

| Micrometastasis | 1 (2) |

| Macrometastases | 8 (17) |

| Unknown | 11 (23) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 11 (23) |

| Absent | 36 (77) |

| ER status | |

| Positive | 3 (6) |

| Negative | 34 (72) |

| Unknown | 10 (21) |

| PR status | |

| Positive | 4 (9) |

| Negative | 32 (68) |

| Unknown | 11 (23) |

| HER2 status | |

| Positive | 0 (0) |

| Negative | 22 (47) |

| Unknown | 25 (53) |

| Percentage of sarcomatoid component | |

| >95% | 25 (53) |

| >50% and ≤95% | 8 (17) |

| ≤50% | 14 (30) |

| Type of sarcomatoid component | |

| Spindle cell | 34 (72) |

| Spindle cell + other | 9 (19) |

| Other | 4 (9) |

| Type of carcinomatous component | |

| Ductal | 38 (81) |

| Squamous | 3 (6) |

| Ductal + squamous | 2 (4) |

| None | 4 (9) |

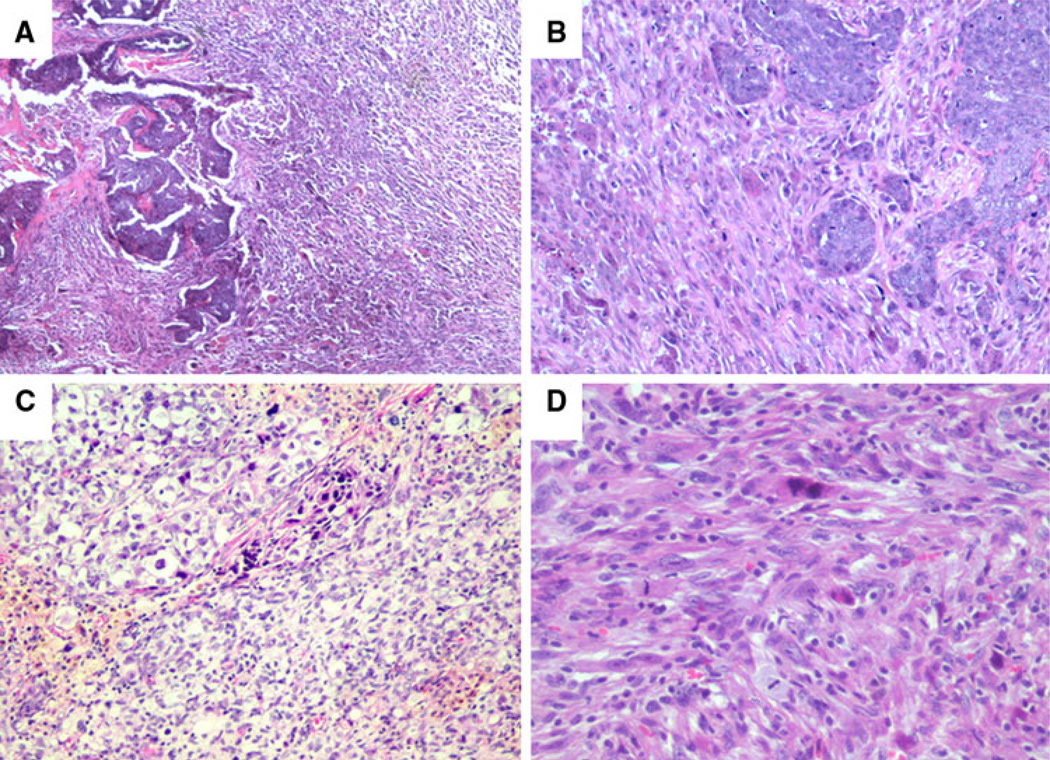

Most of the patients in this study had tumors with a large sarcomatoid component. Tumor cells with sarcomatoid morphology comprised >95% of 25 cases (53%) and ≤25% of 14 cases (30%) (Fig. 1). The sarcomatoid component in 34 patients (72%) was composed entirely of spindled tumor cells. The sarcomatoid component of 2 patients (4%) had a malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)-like appearance, 1 patient (2%) had a pleomorphic sarcomatoid component, and 1 patient (2%) had an osseous component with osteoclast-like giant cells. Nine additional patients (19%) had a sarcomatoid component containing spindled tumor cells admixed with osseous, chondroid, myxoid, pleomorphic, or rhabdoid elements. Sixteen patients (34%) had an intermediate-grade sarcomatoid component, and 31 (66%) had a high-grade sarcomatoid component. Among the 22 patients with an overt carcinomatous component comprising at least 5% of the tumor, the carcinomatous component was low grade in 1 patient (5%), intermediate grade in 6 patients (27%), and high grade in 15 (68%). Seventeen of these (77%) had ductal differentiation, 3 (14%) had squamous differentiation, and 2 (9%) had mixed ductal and squamous differentiation.

Fig. 1.

Representative cases of metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma with varying amounts of carcinomatous and sarcomatous components (a–c) or pure sarcomatoid morphology (d)

The primary surgical treatment for 22 patients (47%) was breast-conserving surgery. Twenty-five patients (53%) underwent total mastectomy. Axillary lymph node status was available for 36 patients (77%) who underwent either complete axillary dissection or limited axillary node excision, including sentinel node biopsy. Lymph node macrometastases were identified in 8 patients (22%). The primary tumor in these eight patients had a carcinomatous component comprising 75–90% of the tumor. One patient with a carcinomatous component comprising <5% of the primary tumor had a micrometastasis, and one patient without an overt carcinomatous component in the primary tumor had only isolated tumor cells in a lymph node.

Thirty-eight patients received chemotherapy, 32 patients received radiation therapy, and five patients received hormonal therapy. Information on treatment with chemotherapy or radiation was unavailable for three patients, and information on hormonal therapy was unavailable for four patients. Clinical follow-up was available for 43 patients and ranged from 4 to 214 months (median 30 months). Of these, 12 patients (28%) had a local or regional recurrence, 17 patients (40%) developed distant metastases, and 9 (21%) had both. There were 23 deaths (53%), 17 of which (40%) were breast cancer related. For the entire group, 5-year disease-free survival was 45 ± 8%.

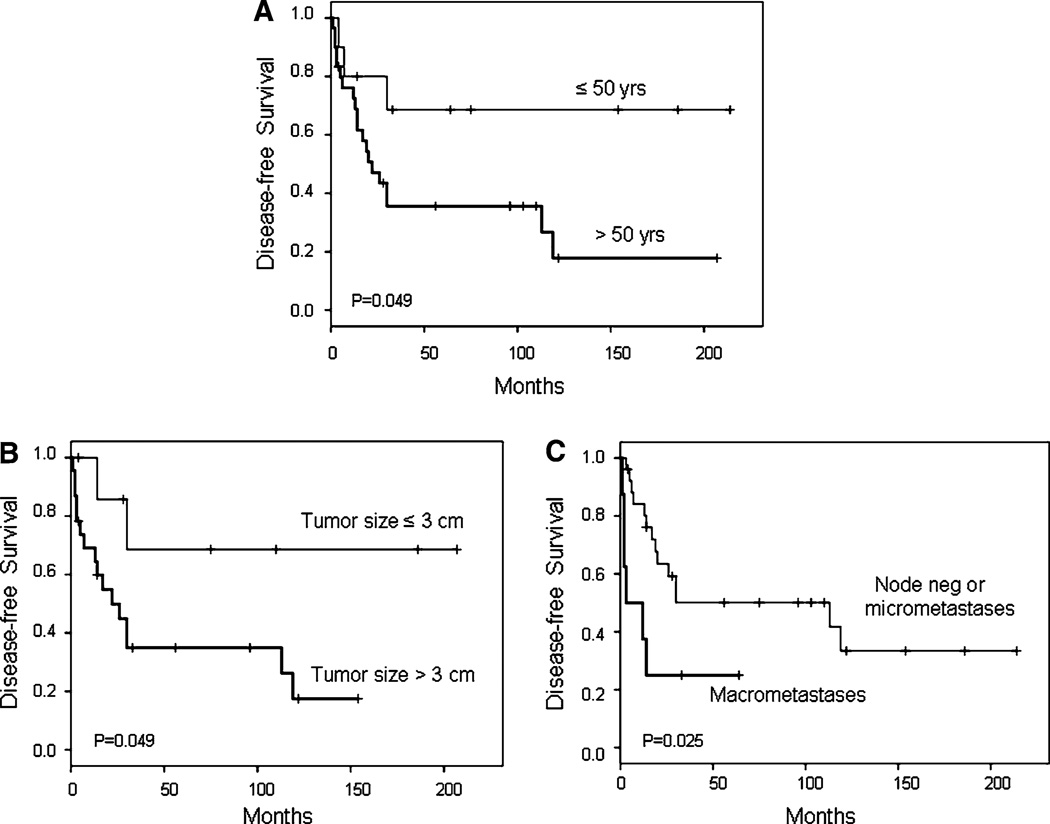

Forty patients had stage I–III disease and available clinical follow-up data. Among these patients, factors significantly associated with reduced disease-free survival were patient age > 50 years (P = 0.049), tumor size >3 cm (P = 0.049), and the presence of lymph node macrometastases (P = 0.025) (Fig. 2). Five-year disease-free survival was 36 ± 9% versus 68 ± 16% for patients >50 years of age versus ≤50 years of age, respectively; 34 ± 11% versus 70 ± 18% for patients with tumors >3 versus ≤3 cm, respectively; and 25 ± 15% versus 51 ± 10% for patients with macrometastases versus negative lymph nodes or micrometastases, respectively. In multivariate analysis, patient age >50 years (HR 10.12, 95% CI 1.26–81.31, P = 0.029) and the presence of macrometastases (HR 6.47, 95% CI 1.87–22.36, P = 0.003) each maintained independent adverse prognostic significance.

Fig. 2.

Disease-free survival for stage I–III MSC patients according to patient age (a), tumor size (b), and lymph node status (c)

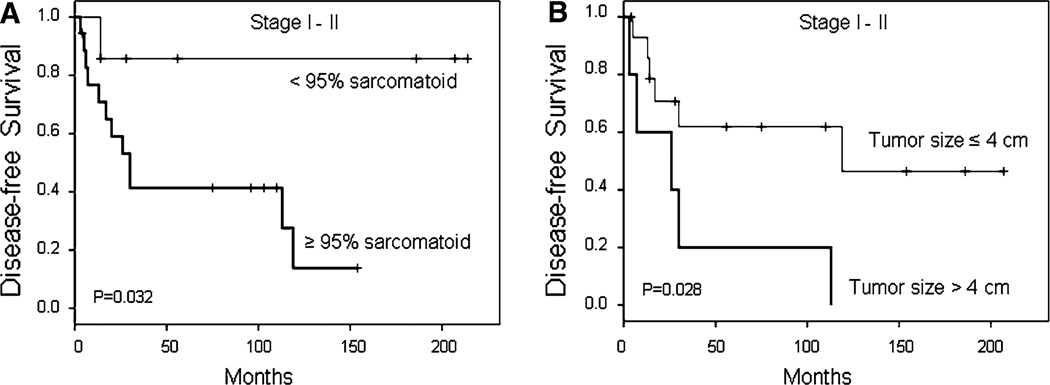

When analysis was restricted to patients with early-stage (stage I–II) disease, factors significantly associated with disease-free survival were a sarcomatoid component comprising ≥95% of the tumor (P = 0.032) and tumor size >4 cm (P = 0.028) (Fig. 3). Five-year disease-free survival was 42 ± 12% versus 85 ± 14% for patients with a sarcomatoid component comprising ≥95% of the tumor versus patients with a smaller proportion of sarcomatoid component, respectively; and 20 ± 18% versus 62 ± 13% for patients with tumors >4 versus ≤4 cm, respectively. In multivariate analysis, only tumor size >4 cm (HR 3.61, 95% CI 1.04–12.51, P = 0.043) maintained independent adverse prognostic significance.

Fig. 3.

Disease-free survival for early-stage (stage I–II) MSC patients according to proportion of sarcomatoid component (a) and tumor size (b)

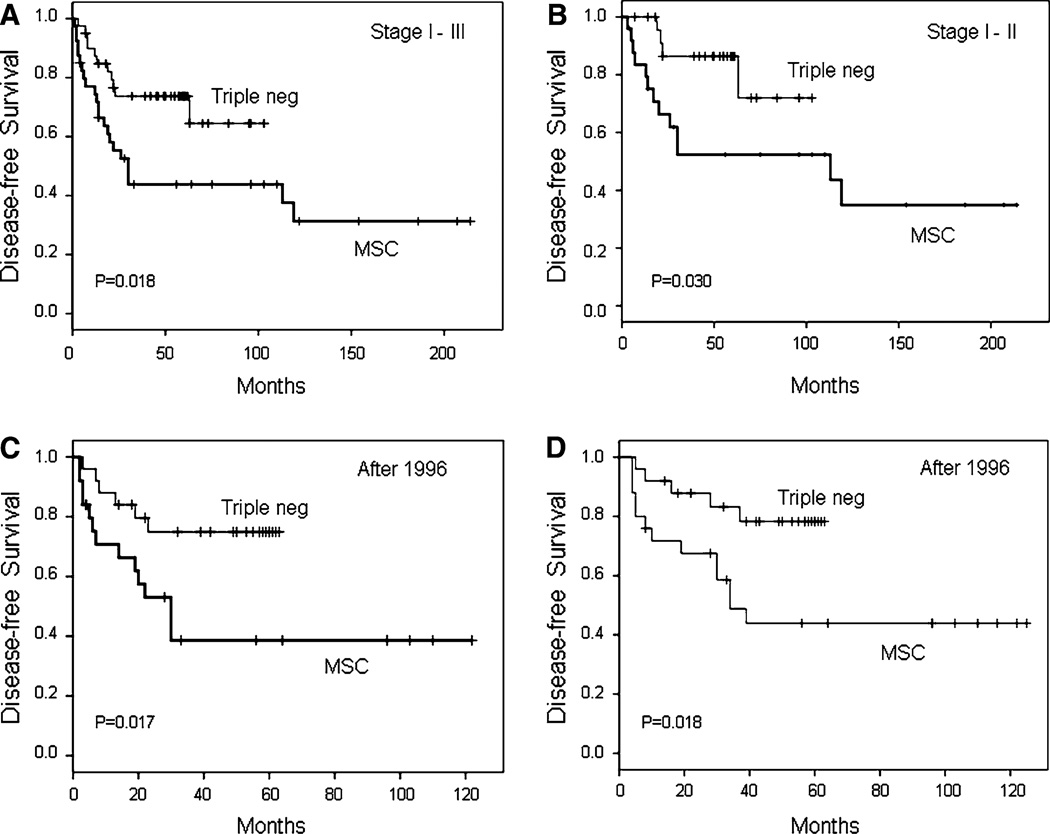

Survival estimates for patients with stage I–III MSC were compared to a control group of triple receptor-negative breast cancer patients matched as closely as possible for patient age, clinical stage, tumor grade, treatment with chemotherapy, and treatment with radiation therapy (see ‘‘Materials and Methods’’ section). Total mastectomy was performed for 20 MSC patients (50%) and 19 control patients (47%), and breast-conserving surgery was performed for 20 MSC patients (50%) and 21 control patients (53%). Compared to the control group of triple receptor-negative patients, patients with stage I–III MSC had decreased disease-free survival (P = 0.018) (Fig. 4a). Five-year disease-free survival was 44 ± 8% versus 74 ± 7% for patients with MSC versus triple receptor-negative breast cancer, respectively. Similarly, patients with early-stage (stage I–II) MSC had decreased disease-free survival (P = 0.030) compared to matched triple receptor-negative controls (Fig. 4b). Five-year disease-free survival was 53 ± 10% versus 87 ± 7% for patients with MSC versus triple receptor-negative breast cancer, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Disease-free survival for stage I–III MSC patients versus triple-negative breast cancer patients (a) and for early-stage (stage I–II) MSC patients versus triple-negative breast cancer patients (b). Disease-free survival for stage I–III MSC patients diagnosed and treated after 1996 versus triple-negative patients (c), and overall survival for stage I–III MSC patients diagnosed and treated after 1996 versus triple-negative patients (d)

Because HER2 testing was not routinely performed at MDACC before 1997, control patients selected from the triple receptor-negative database were all diagnosed and treated after 1996 (later than some of the patients with MSC). Therefore, survival analysis was also performed on the subset of 25 MSC patients diagnosed and treated after 1996 and their matched triple receptor-negative control patients. In this subset of patients diagnosed and treated after 1996, patients with MSC had not only decreased disease-free survival (P = 0.017) (Fig. 4c) but also decreased overall survival (P = 0.018) (Fig. 4d). Five-year disease-free survival was 39 ± 11% versus 75 ± 9% for patients with MSC versus triple receptor-negative patients, respectively. Five year overall survival was 44 ± 10% versus 78 ± 9% for patients with MSC versus triple receptor-negative patients, respectively.

Discussion

Invasive breast cancers with an intermediate to high-grade sarcomatoid component admixed with a carcinomatous component have been regarded as carcinosarcomas by some authors [1]. Others have used the term carcinosarcoma in a very restricted sense to include only tumors in which the carcinomatous and sarcomatous components appear derived from separate epithelial and mesenchymal precursors, such as carcinoma arising within a malignant phyllodes tumor [16]. Preference for the term sarcomatoid carcinoma for most tumors with mixed sarcomatous and carcinomatous components has been based on their presumed histogenesis. The malignant glands in some tumors appear to merge contiguously with malignant spindle cells. This observation, together with frequent immunohisto-chemical expression of keratin within the spindle cell component [3, 17–19], has suggested to many authors that the malignant spindle cells are derived from the carcinomatous component [20]. Molecular studies do, in fact, demonstrate clonality in these tumors, but they may actually be derived from stem cell-like precursors with the capacity for epithelial, myoepithelial and mesenchymal differentiation [21, 22].

Although metaplastic carcinomas of the breast are histologically diverse, this study focused on metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma (MSC), the subtype composed of overt carcinoma admixed with a mesenchymal component that appears morphologically malignant. Other specific forms of metaplastic carcinoma, such as low-grade fibromatosis-like metaplastic tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, matrix-producing carcinoma, and squamous carcinoma were excluded. Low-grade fibromatosis-like metaplastic tumors and low-grade adenosquamous carcinomas have been shown to be relatively indolent [12–15], and reports on the clinical behavior of squamous carcinomas of the breast have been contradictory [6, 23–26]. Matrix-producing carcinoma may be similar in behavior to MSC [8], but it is morphologically distinct. We chose to focus this study on MSC because we believed it to be an aggressive subtype and wanted to confirm whether this well-defined subgroup of metaplastic carcinomas was indeed more aggressive than other triple-negative breast cancers.

We found that patients with MSC have decreased disease-free survival compared to other patients with triple-negative breast cancer. We also found that, in the subgroup of patients diagnosed and treated after 1996, patients with MSC had decreased overall survival compared to other triple-negative breast cancer patients. Although multivariate analysis was limited by the relatively small number of patients, age >50 years and the presence of macrometastases were found to be independent predictors of decreased disease-free survival. We thought the percentage of sarcomatoid component might be prognostically important, and there was indeed decreased disease-free survival for early-stage (stage I–II) MSC patients with a sarcomatoid component comprising ≥95% of the tumor. However, most patients with ≥95% sarcomatoid morphology in this study had large tumors, and only tumor size >4 cm maintained independent adverse prognostic significance in multivariate analysis. For the entire group of MSC patients, those with macrometastases had the worst outcome.

For MSC patients with a sarcomatoid component comprising ≥ 95% of the tumor, the likelihood of axillary involvement appears to be exceedingly low. For these patients, as well as those with low-grade fibromatosis-like metaplastic tumor [12, 13] and low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma [14, 15], a surgical approach to axillary evaluation may not be necessary unless (as with patients with primary sarcoma of the breast) there is clinical suspicion of lymph node involvement. It is currently unknown if adjuvant radiotherapy benefits patients with MSC, but given the high rate of local failure in patients with MSC, maximal local therapy seems appropriate.

Conventional systemic chemotherapy appears to be less effective for MSC than for invasive ductal carcinoma [26–29]. In a recent study [29], for example, a pathologic complete response rate of 10% and a combined clinical partial and complete response rate of 26% was observed among 21 patients with MSC treated with primary chemotherapy. This is considerably lower than the response rate of invasive ductal carcinoma, particularly when one considers that metaplastic carcinomas have been regarded as basal-like breast cancers, which have a high rate of response to primary chemotherapy.

Some important differences have been observed at the molecular level, however, between metaplastic carcinomas and basal-like breast cancers. A large number of genes are differentially expressed [30, 31]. Over 60% of metaplastic breast carcinomas are reported to have BRCA1 gene promoter methylation [32], and there is greater downregulation of the BRCA1 pathway in metaplastic carcinomas [31]. Data derived in part from a subset of the tumors in this study indicate that PTEN and TOP2A are both downregulated in metaplastic carcinomas [30], a finding which may help us to explain why metaplastic carcinomas generally have a poor response to chemotherapy. In contrast, a number of genes related to myoepithelial differentiation and epithelialmesenchymal transition (EMT) are significantly upregulated in metaplastic carcinomas [30].

Genomic differences between metaplastic carcinomas and basal-like breast cancers have also been reported, such as increased PIK3CA and PI3K/AKT mutations in metaplastic carcinomas and gains in AKT1 and AKT2 gene copy numbers [30]. Moreover, PI3K/AKT pathway components have been found generally to be more highly phosphorylated in metaplastic carcinomas compared to most other breast tumor subtypes [30]. Although most of these data were derived from a mixed group of MSC and squamous carcinomas of the breast [30], the findings likely contribute to the poor clinical outcome of MSC and may provide novel therapeutic targets for these tumors in the future.

Conclusion

This study shows that MSC appears more aggressive than other triple-negative breast cancers. Optimal systemic therapies are still lacking, but new information about molecular pathologic features of these tumors may result in novel therapeutic targets in the future. Aggressive local therapy appears warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Cancer Center Support Grant # CA16672 from the NCI.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None.

Contributor Information

T. R. Lester, Department of Pathology, Unit 85, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030, USA

K. K. Hunt, Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

K. M. Nayeemuddin, Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

R. L. Bassett, Jr, Department of Biostatistics, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

A. M. Gonzalez-Angulo, Department of Breast Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, US Department of Systems Biology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, US.

B. W. Feig, Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

L. Huo, Department of Pathology, Unit 85, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030, USA

L. L. Rourke, Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

W. G. Davis, Department of Pathology, Unit 85, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030, USA

V. Valero, Department of Breast Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, US

M. Z. Gilcrease, Email: mgilcrease@mdanderson.org, Department of Pathology, Unit 85, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

References

- 1.Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. III. Carcinosarcoma. Cancer. 1989;64:1490–1499. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891001)64:7<1490::aid-cncr2820640722>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutmann JL. Biologic perspectives to support clinical choices in root canal treatment. Aust Endod J. 2005;31:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2005.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wargotz ES, Deos PH, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. II. Spindle cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:732–740. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast I. Matrix-producing carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:628–635. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast: V. Metaplastic carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:1142–1150. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90151-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. IV. Squamous cell carcinoma of ductal origin. Cancer. 1990;65:272–276. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900115)65:2<272::aid-cncr2820650215>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, Burstein HJ, Carter WB, Edge SB, Erban JK, Farrar WB, Goldstein LJ, Gradishar WJ, Hayes DF, Hudis CA, Jahanzeb M, Kiel K, Ljung BM, Marcom PK, Mayer IA, McCormick B, Nabell LM, Pierce LJ, Reed EC, Smith ML, Somlo G, Theriault RL, Topham NS, Ward JH, Winer EP, Wolff AC. Breast cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7:122–192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downs-Kelly E, Nayeemuddin KM, Albarracin C, Wu Y, Hunt KK, Gilcrease MZ. Matrix-producing carcinoma of the breast: an aggressive subtype of metaplastic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:534–541. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31818ab26e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis WG, Hennessy B, Babiera G, Hunt K, Valero V, Buchholz TA, Sneige N, Gilcrease MZ. Metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the breast with absent or minimal overt invasive carcinomatous component: a misnomer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1456–1463. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176431.96326.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter MR, Hornick JL, Lester S, Fletcher CD. Spindle cell (sarcomatoid) carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:300–309. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000184809.27735.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman MW, Marti JR, Gallager HS, Hoehn JL. Carcinoma of the breast with pseudosarcomatous metaplasia. Cancer. 1984;53:1908–1917. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<1908::aid-cncr2820530917>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sneige N, Yaziji H, Mandavilli SR, Perez ER, Ordonez NG, Gown AM, Ayala A. Low-grade (fibromatosis-like) spindle cell carcinoma of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1009–1016. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobbi H, Simpson JF, Borowsky A, Jensen RA, Page DL. Metaplastic breast tumors with a dominant fibromatosis-like phenotype have a high risk of local recurrence. Cancer. 1999;85:2170–2182. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2170::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen PP, Ernsberger D. Low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma. A variant of metaplastic mammary carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:351–358. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198705000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Hoeven KH, Drudis T, Cranor ML, Erlandson RA, Rosen PP. Low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma of the breast. A clinicopathologic study of 32 cases with ultrastructural analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:248–258. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azzopardi JG. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1979. Problems in breast pathology. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitts WC, Rojas VA, Gaffey MJ, Rouse RV, Esteban J, Frierson HF, Kempson RL, Weiss LM. Carcinomas with metaplasia and sarcomas of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:623–632. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/95.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis IO, Bell J, Ronan JE, Elston CW, Blamey RW. Immunocytochemical investigation of intermediate filament proteins and epithelial membrane antigen in spindle cell tumours of the breast. J Pathol. 1988;154:157–165. doi: 10.1002/path.1711540208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santeusanio G, Pascal RR, Bisceglia M, Costantino AM, Bosman C. Metaplastic breast carcinoma with epithelial phenotype of pseudosarcomatous components. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koker MM, Kleer CG. p63 expression in breast cancer: a highly sensitive and specific marker of metaplastic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1506–1512. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138183.97366.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada H, Enomoto T, Tsujimoto M, Nomura T, Murata Y, Shroyer KR. Carcinosarcoma of the breast: molecular-biological study for analysis of histogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1324–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teixeira MR, Qvist H, Bohler PJ, Pandis N, Heim S. Cytogenetic analysis shows that carcinosarcomas of the breast are of monoclonal origin. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;22:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toikkanen S. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast. Cancer. 1981;48:1629–1632. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811001)48:7<1629::aid-cncr2820480726>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cardoso F, Leal C, Meira A, Azevedo R, Mauricio MJ, Leal da Silva JM, Lopes C, Pinto Ferreira E. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast. Breast. 2000;9:315–319. doi: 10.1054/brst.1999.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eggers JW, Chesney TM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathologic analysis of eight cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:526–531. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hennessy BT, Krishnamurthy S, Giordano S, Buchholz TA, Kau SW, Duan Z, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7827–7835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rayson D, Adjei AA, Suman VJ, Wold LE, Ingle JN. Metaplastic breast cancer: prognosis and response to systemic therapy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:413–419. doi: 10.1023/a:1008329910362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberman HA. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast. A clinicopathologic study of 29 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:918–929. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198712000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hennessy BT, Giordano S, Broglio K, Duan Z, Trent J, Buchholz TA, Babiera G, Hortobagyi GN, Valero V. Biphasic metaplastic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the breast. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:605–613. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Gilcrease MZ, Krishnamurthy S, Lee JS, Fridlyand J, Sahin A, Agarwal R, Joy C, Liu W, Stivers D, Baggerly K, Carey M, Lluch A, Monteagudo C, He X, Weigman V, Fan C, Palazzo J, Hortobagyi GN, Nolden LK, Wang NJ, Valero V, Gray JW, Perou CM, Mills GB. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4116–4124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weigelt B, Kreike B, Reis-Filho JS. Metaplastic breast carcinomas are basal-like breast cancers: a genomic profiling analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS, Russell AM, Springall RJ, Ryder K, Steele D, Savage K, Gillett CE, Schmitt FC, Ashworth A, Tutt AN. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]