Abstract

Onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) plays a causative role in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Current therapeutic strategies for reducing reperfusion injury remain disappointing. Autophagy is a lysosome-mediated, catabolic process that timely eliminates abnormal or damaged cellular constituents and organelles such as dysfunctional mitochondria. I/R induces calcium overloading and calpain activation, leading to degradation of key autophagy-related proteins (Atg). Carbamazepine (CBZ), an FDA-approved anticonvulsant drug, has recently been reported to increase autophagy. We investigated the effects of CBZ on hepatic I/R injury. Hepatocytes and livers from male C57BL/6 mice were subjected to simulated in vitro, as well as in vivo I/R, respectively. Cell death, intracellular calcium, calpain activity, changes in autophagy-related proteins (Atg), autophagic flux, MPT and mitochondrial membrane potential after I/R were analyzed in the presence and absence of 20 µM CBZ. CBZ significantly increased hepatocyte viability after reperfusion. Confocal microscopy revealed that CBZ prevented calcium overloading, the onset of the MPT and mitochondrial depolarization. Immunoblotting and fluorometric analysis showed that CBZ blocked calpain activation, depletion of Atg7 and Beclin-1 and loss of autophagic flux after reperfusion. Intravital multiphoton imaging of anesthetized mice demonstrated that CBZ substantially reversed autophagic defects and mitochondrial dysfunction after I/R in vivo. In conclusion, CBZ prevents calcium overloading and calpain activation, which, in turn, suppresses Atg7 and Beclin-1 depletion, defective autophagy, onset of the MPT and cell death after I/R.

Keywords: mitochondria, autophagy, mitochondrial permeability transition, hepatocytes, ischemia/reperfusion, calcium

Introduction

Liver ischemia during transplantation, hepatectomy, cardiac failure and hemorrhagic shock causes anoxia, depletion of glycolytic substrates, loss of ATP and acidosis. When blood flow returns to livers, the normal oxygen concentration and pH are restored, however, paradoxically, hepatic injury is prominent upon reperfusion (Kim et al., 2008). In the liver and other tissues, reperfusion causes onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), leading to uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death (Kim et al., 2008). Clinical outcomes from mitochondria-targeted therapies, however, remain disappointing largely due to the complex and integrated nature of mitochondrial dysfunction after I/R.

Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy hereafter) is a lysosome-dependent cellular process that eliminates surplus or dysfunctional cytoplasmic proteins and organelles in a timely fashion. Autophagy is a primary catabolic process of hepatic proteins and confers cytoprotection against I/R liver injury (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Mitophagy is a selective mitochondrial autophagy that targets and removes damaged or abnormal mitochondria (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Hence, accelerating mitophagy may have a therapeutic potential for mitochondria-related diseases such as I/R injury. Indeed, overexpression of specific autophagy genes alleviates the MPT onset and mitochondrial dysfunction in both in vitro and in vivo I/R (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011).

Despite a therapeutic potential., current strategies to accelerate autophagy, either genetically or pharmacologically, still face numerous obstacles. Major shortcomings surrounding gene therapy include issues on safety, delivery efficiency, immune response, mutagenesis and ethical concerns (Verma et al., 1997). Pharmacological enhancement of autophagy also presents a number of issues. Although rapamycin and its analogues are the most well-characterized autophagy inducers, they have serious adverse effects, including immunosuppression and hyperlipidemia (Brattstrom et al., 1998; Hartford et al., 2007). Recently, carbamazepine (CBZ), an FDA approved anticonvulsant and mood stabilizing drug, has been reported to stimulate autophagy by decreasing intracellular levels of inositol (Williams et al., 2008). How CBZ affects I/R-mediated autophagy defects in livers is currently unknown.

In the present study, we demonstrate that, in both in vitro and in vivo models of I/R, CBZ alleviates lethal reperfusion injury by preventing a temporal sequence of calcium overloading, calpain activation, Atg7 and Beclin-1 depletion, defective autophagy, onset of the MPT and cell death.

Material and methods

Reagents

Fluo-4/AM, xRhod-1/AM, tetramethylrhodamine methylester and calcein/AM were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Embedding agents for transmission electron microscopy were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louise, MO) except if noted otherwise.

Hepatocyte isolation and culture

Animals received humane care according to protocols approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the University of Florida. 3-month-old male C57BL/6 mice were housed in a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle, and temperature-controlled room. Mice were fed a standard chow with free access to water. Hepatocytes were isolated by the collagenase perfusion method and cultured overnight in Waymouth’s medium, as previously described (Kim et al., 2003a). Cell viability after isolation, as determined by trypan blue exclusion, was consistently greater than 90%. For the cell death assay, aliquots (1 ml) of 1.7 × 105 cells were plated onto 24-well microtiter plates (Falcon, Lincoln Park, NJ). For immunoblotting analysis of LC3, Atg and calpains, hepatocytes were plated on 35 mm culture dishes at a concentration of 106 cells. For confocal microscopic studies, 4.0 × 105 cells were cultured on 42 mm round glass coverslips in 60 mm culture dishes. All plates, dishes and coverslips were coated with 0.1% Type 1 rat tail collagen. Hepatocytes were used after overnight culture in humidified 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C.

Simulated in vitro I/R in cultured mouse hepatocytes

Anoxia in the anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Ann Arbor, MI) was maintained under an atmosphere of 90% N2-10% H2 in the presence of a heated palladium catalyst to convert residual oxygen to water vapor. The anoxic buffer was prepared by equilibrating Krebs-Ringer-N-2 hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2 ethanesulfonic acid buffer (KRH) containing 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4 and 25 mM HEPES (pH 6.2) overnight inside the anaerobic chamber prior to the experiments (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Oxygen tension in the chamber and anoxic buffer was monitored by a gas analyzer (Model 10; Coy Laboratory Products) and was less than 0.001 Torr. To simulate the anoxia, substrate depletion and tissue acidosis of ischemia, hepatocytes were incubated in KRH at pH 6.2 in the anaerobic chamber for 4 hours. To simulate reperfusion and the return to physiological pH, anaerobic KRH at pH 6.2 was replaced with aerobic KRH at pH 7.4. Some hepatocytes were treated with 20 µM CBZ overnight before ischemia and continuously during ischemia.

Cell death assay

Necrosis was assessed by propidium iodide (PI) fluorometry using a multi-well fluorescence scanner (SpectraMax M2; Molecular device, Sunnyvale, CA) (Nieminen et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2003a). To prevent oxygen back diffusion during ischemia, plates were sealed with vacuum tape (3M, Minneapolis, MN) inside the anaerobic chamber.

Hepatocellular loading of xRhod-1, Fluo-4, calcein, TMRM and propidium iodide

To monitor mitochondrial and extramitochondrial Ca2+, hepatocytes on glass coverslips were co-loaded with 10 µM xRhod-1/AM and 10 µM Fluo-4/AM, respectively, in anoxic KRH at 37°C for 30 minutes during ischemia (Kim et al., 2006; Gerencser AA et al., 2001). To image temporal changes of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), onset of the MPT and cell death, hepatocytes cultured on glass coverslips were co-loaded with 100 nM of tetramethylrhodamine methylester (TMRM), 1 µM calcein/AM and 3 µM propidium iodide (PI), respectively, for 30 minutes before reperfusion (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011).

Autophagic flux measurement

For autophagic flux, hepatocytes were treated with 10 µM chloroquine or 100 nM bafilomycin for 3 hours or 20 minutes prior to reperfusion, respectively. Changes in LC3 expression were monitored by immunoblotting.

Adenoviral labeling of GFP-LC3 and mCherry-GFP-LC3

Hepatocytes were infected with adenovirus encoding GFP-LC3 and mCherry-GFP-LC3 at the concentration of 10 MOI (multiplicity of infection) in hormonally defined medium, as previously described (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Adenovirus harboring β-galactosidase (AdLacZ) was used for the viral control. For in vivo livers, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1010 virus particles of adenovirus overnight.

Immunoblotting analysis

Hepatocyte and liver lysates were prepared and expression of Atg7, Beclin-1, LC3-I/II, calpain 2 and β-actin were detected on the same gel using primary polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Changes in protein expression were determined using IMAGE J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Calpain activity assay

The activity of calpains was fluorometrically assessed using 20 µM succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (SLLVY-AMC, Sigma, St. Louise, MO), a membrane-permeable calpain substrate, in the presence and absence of CBZ (Kim et al., 2008).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Glass coverslips containing hepatocytes were mounted in a closed gas-tight cultivation chamber (Zeiss, Germany) inside the anoxic chamber. Confocal images of calcein, Fluo-4, TMRM, GFP-LC3, mCherry-GFP-LC3, PI and xRhod-1 were collected using an inverted Zeiss 510 laser scanning confocal microscope, as previously described (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011).

Transmission electron microscopy

Hepatocytes were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde/125 mM cacodylate/2.2 mM CaCl (pH 7.4) and stained with 1%OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) (Dunn, Jr., 1990). Images were collected with a JEOL 100CX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA).

In vivo I/R

Hepatic ischemia in male C57BL/6 mice was induced by occluding the portal triad for 45 minutes, as previously described (Kim et al., 2008). Reperfusion was initiated by removing a microvascular clamp. Some mice were intraperitoneally injected with CBZ at the concentration of 25 mg/kg of body weight overnight prior to I/R. Liver biopsies from the left lateral lobe were collected during I/R and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for the analysis of autophagy proteins.

Intravital multiphoton microscopy

To visualize autophagosomes and autophagic flux, livers were labeled with adenoviral GFP-LC3 or mCherry-GFP-LC3 (Wang et al., 2011). After 15 minutes of reperfusion in vivo, a 24-gauge catheter was inserted into the portal vein. Rhodamine 123 (50 ml of 10 µM/animal), a Δψm-sensitive fluorophore, was infused for 10 minutes. The liver was gently withdrawn from the abdominal cavity and placed over a glass coverslip on the stage of a Zeiss LSM510 equipped with a multiphoton microscope. Images of green fluorescing rhodamine 123 and GFP-LC3 were collected with a 40× water-immersion objective lens. Rhodamine 123 and GFP-LC3 were excited with 780 nm from a Chameleon Ultra Ti-Sapphire pulsed laser (Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA) and images were collected through 500–550-nm band pass filter. For imaging of mCherry-GFP-LC3, tandem fluorophores were excited at 800 nm and emission was separated through 500–530 nm (GFP) and 565- 615 nm (mCherry) band pass filters. Ten images were randomly collected per each liver. To reconstruct 3-dimensional images of autophagosomes, z-stacks of GFP-LC3 fluorescence were collected at 0.7-µm intervals through a thickness of 70 µm.

Statistics

Differences between means were compared by the Mann-Whitney test using a level of significance of p < 0.05. Data were expressed as means ± SE. Results were representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Results

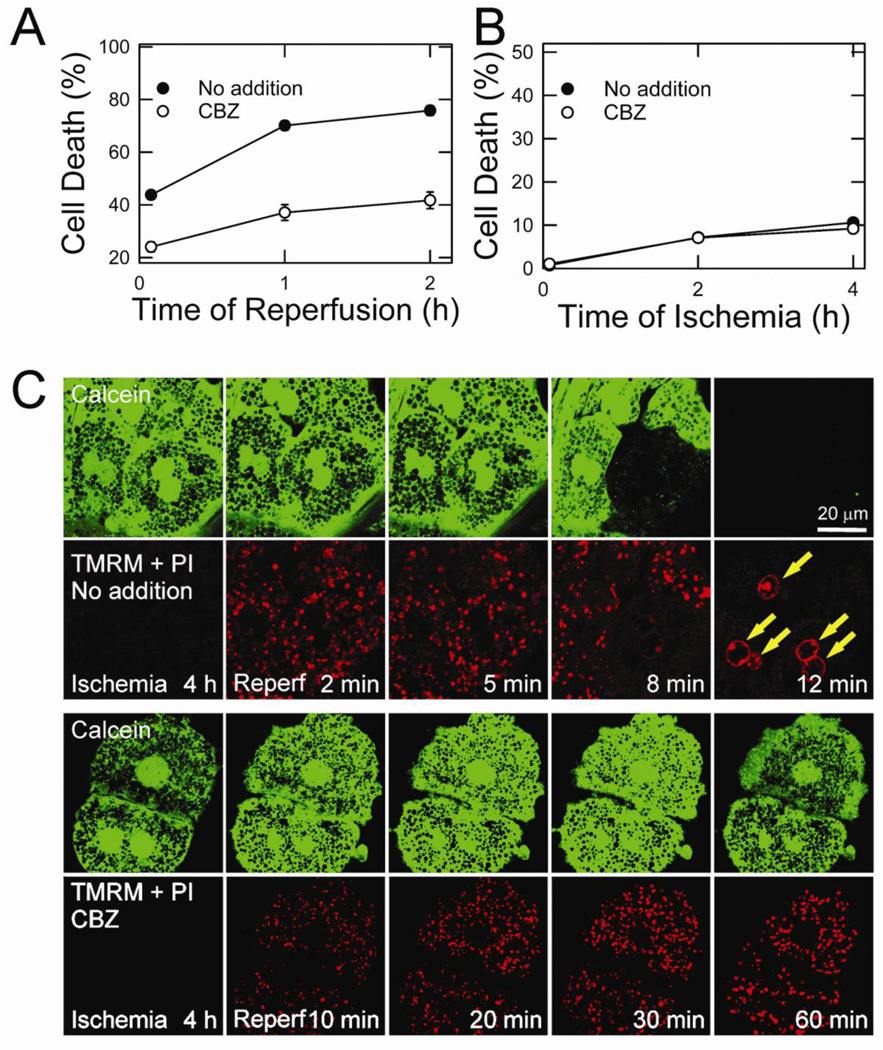

CBZ protects mouse hepatocytes against I/R injury

After 4 hours of simulated in vitro ischemia (referred to simply as “ischemia”), hepatocytes were exposed to aerobic KRH at pH 7.4 to simulate reperfusion (referred to simply as “reperfusion”). PI fluorometry showed that CBZ significantly suppressed necrotic cell death after reperfusion (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous reports (Qian et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2003c; Kim et al, 2012), cell death during ischemia was minimal and CBZ did not affect cell viability during 4 hours of ischemia (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Cytoprotection by CBZ against MPT-dependent cell death.

(A) Necrosis at 5, 60 and 120 minutes of reperfusion was measured by PI fluorometry. (B) Necrosis at 5, 120 and 240 minutes of ischemia was determined. (C) After 4 hours of ischemia, control (top panels) and CBZ-treated hepatocytes (bottom panels) were reperfused and confocal images of calcein, TMRM and PI (arrows) were simultaneously collected.

CBZ blocks onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition after I/R

Reperfusion causes the onset of the MPT, leading to uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria and cell death (Kim et al., 2003a; Kim et al., 2003b; Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011. To investigate whether cytoprotection by CBZ is associated with an inhibition of the MPT, the opening of permeability transition pores, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and cell death were simultaneously imaged using laser scanning confocal microscopy of calcein, tetramethylrhodamine methylester (TMRM) and PI, respectively (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011) (Fig. 1C). Since polarized mitochondria take up TMRM while simultaneously excluding calcein, the mitochondria in the green channel appear as dark and round voids where each void represents a single, polarized mitochondrion. After 4 hours of ischemia, TMRM fluorescence was barely detectable in both control and CBZ-treated hepatocytes due to anoxic mitochondrial depolarization. These mitochondria, however, excluded calcein, indicating a lack of MPT onset during ischemia. Within 5 minutes of reperfusion, the mitochondria in control hepatocytes repolarized, but began losing TMRM fluorescence after 8 minutes (Fig. 1C, top panels). As the mitochondria lost Δψm, calcein redistributed from the cytosol to the mitochondria, an event signifying the MPT (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Both calcein and TMRM fluorescence completely disappeared at 12 minutes in conjunction with PI labeling in the nuclei (arrows) due to the loss of the plasma membrane integrity. In striking contrast, CBZ-treated hepatocytes sustained Δψm, and continuously excluded calcein in the mitochondria and PI in the nuclei after reperfusion (Fig. 1C, bottom panels), showing that CBZ inhibits the onset of the MPT, mitochondrial depolarization and necrosis after I/R. Therefore, cytoprotection by CBZ stems from its blockade of the MPT, a causative mechanism leading to hepatocyte I/R injury.

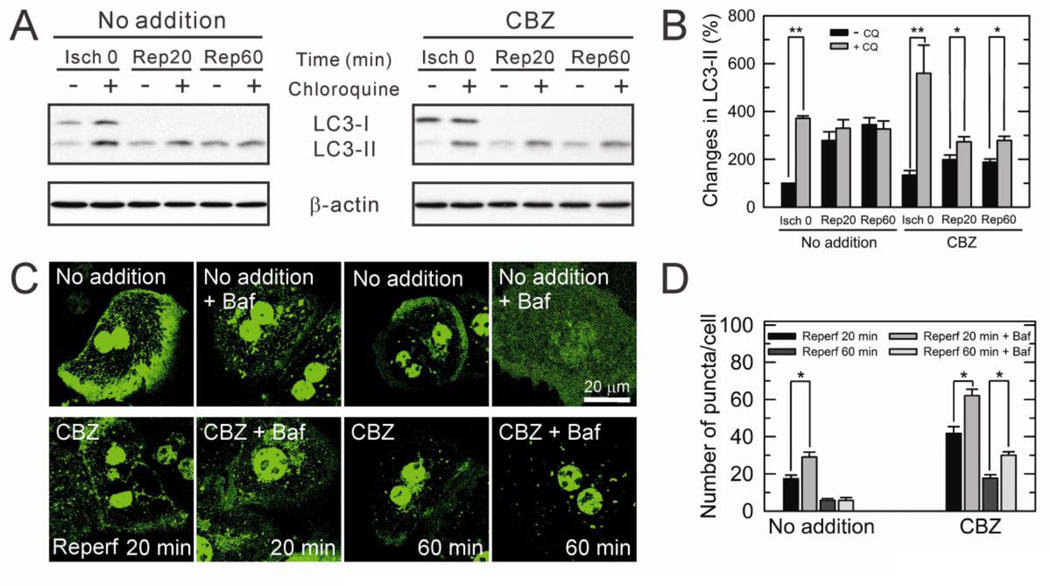

CBZ suppresses defective autophagy after I/R

Autophagy is a lysosome-dependent catabolic process that removes unnecessary or dysfunctional cellular components in a timely manner (Yorimitsu et al., 2005). Thus, impaired or insufficient autophagy can lead to tissue injury. We have shown that I/R in rodent livers causes defective autophagy, subsequently leading to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, onset of the MPT and ultimately cell death after reperfusion (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). To examine whether CBZ-mediated cytoprotection is associated with autophagy, autophagic flux, a dynamic indicator of autophagic activity (Wang et al., 2011), was determined with immunoblotting of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) in the presence and absence of bafilomycin A1 or chloroquine (CQ), specific lysosomotropic reagents that block lysosomal acidification and the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes (Wang et al., 2011). In control cells, hepatocytes sustained autophagic flux prior to onset of ischemia, as judged by a substantial increase in LC3-II by CQ (Fig. 2A and B). However, upon reperfusion, the accumulation of LC3-II by CQ was minimal., indicating a deficient autophagic flux after I/R. On the contrary, in CBZ-treated hepatocytes, a significant accumulation of LC3-II by CQ was evident throughout the course of reperfusion, demonstrating a robust autophagic flux with CBZ. It also appears that a basal autophagic flux with CBZ is higher than that without it, albeit statistically not significant. To confirm sustained autophagic flux by CBZ, hepatocytes were labeled with GFP-LC3 and the distribution of LC3 before and after bafilomycin treatment was visualized with a confocal microscope (Fig. 2C and D). When autophagy is activated, LC3-I is activated to LC3-II, and targeted to autophagosomes (Wang et al., 2011). Hence, the appearance of LC3-II as green fluorescing punctate structures reflexes active autophagosome formation. Similar to immunoblotting analysis above, CBZ-treated hepatocytes exhibited numerous LC3-II puncta in the presence of bafilomycin during 60 minutes of reperfusion, whereas control cells minimally accumulated green puncta only during 20 minutes of reperfusion. During the earlier stages of reperfusion when onset of the MPT is yet to occur (Qian et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2003c; Kim et al., 2012), most cells remained viable. However, CBZ-treated hepatocytes had substantially more autophagosomes that control cells (supplemental Fig. 1

Fig. 2. Prevention of impaired autophagic flux by CBZ.

(A) Autophagic flux was determined in hepatocyte lysates collected at 0 minute of ischemia (Isch) and at 20 and 60 minutes after reperfusion (Rep). LC3 was immunoblotted with and without 10 µM chloroquine (CQ). (B) LC3-II expression was assessed relative to the level in control hepatocytes at Isch 0 and expressed as percent change. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. (C) Hepatocytes infected with adenovirus harboring GFP-LC3 were subjected to I/R. Confocal images were collected at 20 and 60 minutes after reperfusion with and without 100 nM bafilomycin (Baf). (D) For quantitative analysis of GFP-LC3 fluorometry, ten images were randomly collected per analysis and green puncta/cell were counted. *P < 0.05.

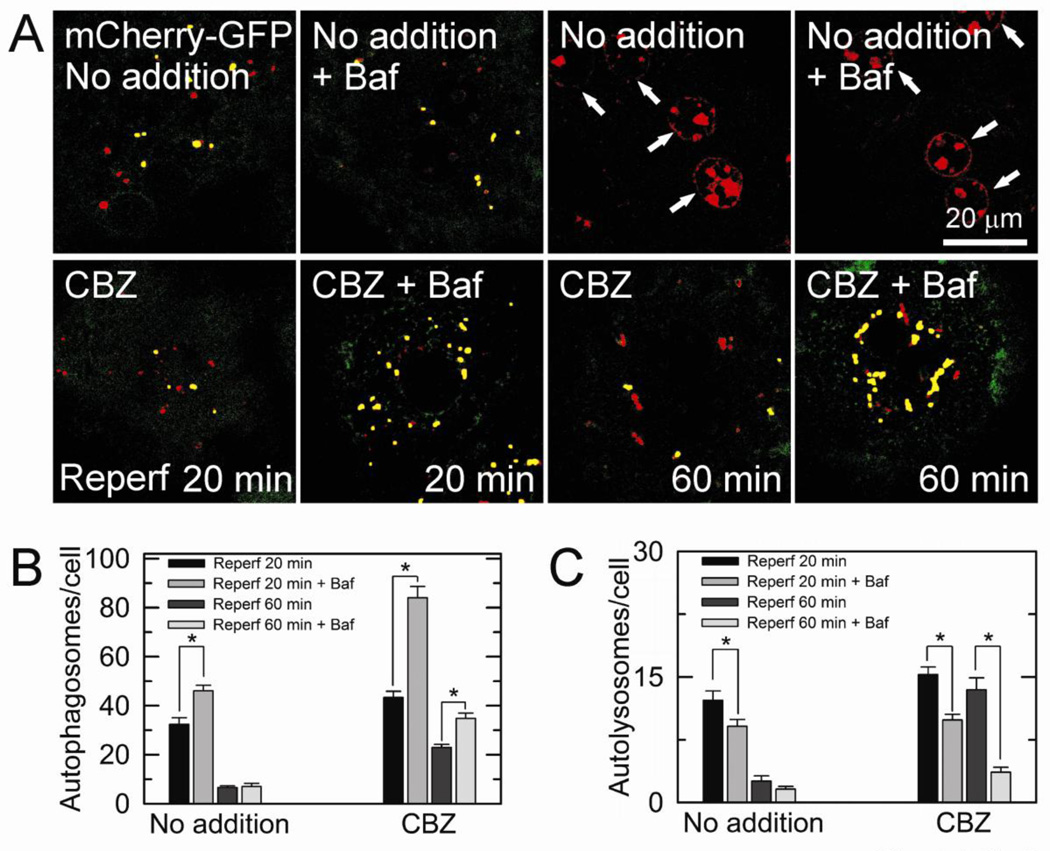

Tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 is an autophagic flux marker that enables simultaneous estimation of both the induction of autophagy and clearance (Wang et al., 2011; Kimura et al., 2007). In the acidic environment autolysosomes, red fluorescence of mCherry retains its fluorescence, while GFP loses its fluorescence. As a result, autophagosomes possess both red and green fluorescence, generating yellow puncta, whereas autolysosomes have only red fluorescence. With confocal microscopy of adenoviral tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3, we analyzed autophagic flux after reperfusion (Fig. 3). There were numerous red puncta (autolysosomes) in CBZ-treated cells during 60 minutes of reperfusion, indicative of a robust autolysosomal clearance by CBZ. Furthermore, the addition of bafilomycin markedly increased yellow puncta (autophagosomes), in parallel with a substantial decrease in red puncta, confirming an active autophagic flux in CBZ-treated hepatocytes. However, in control hepatocytes, bafilomycin-induced accumulation of yellow puncta was evident only the early stage of reperfusion but the extent of accumulation was substantially lower than CBZ-treated cells. After 60 minutes of reperfusion, most cells were non-viable (arrows). Collectively, these results firmly demonstrate that CBZ enhances autophagic flux in reperfused hepatocytes.

Fig. 3. Confocal analysis of autophagic flux with a tandem fluorescent probe.

(A) Hepatocytes infected with adenovirus encoding mCherry-GFP-LC3 were subjected to I/R. Confocal images of yellow (autophagosomes) and red (autolysosomes) puncta were acquired at 20 and 60 minutes after reperfusion with and without bafilomycin (Baf). The number of autophagosomes (B) and autolysosomes (C) was counted after reperfusion in the presence and absence of CBZ. *P < 0.05.

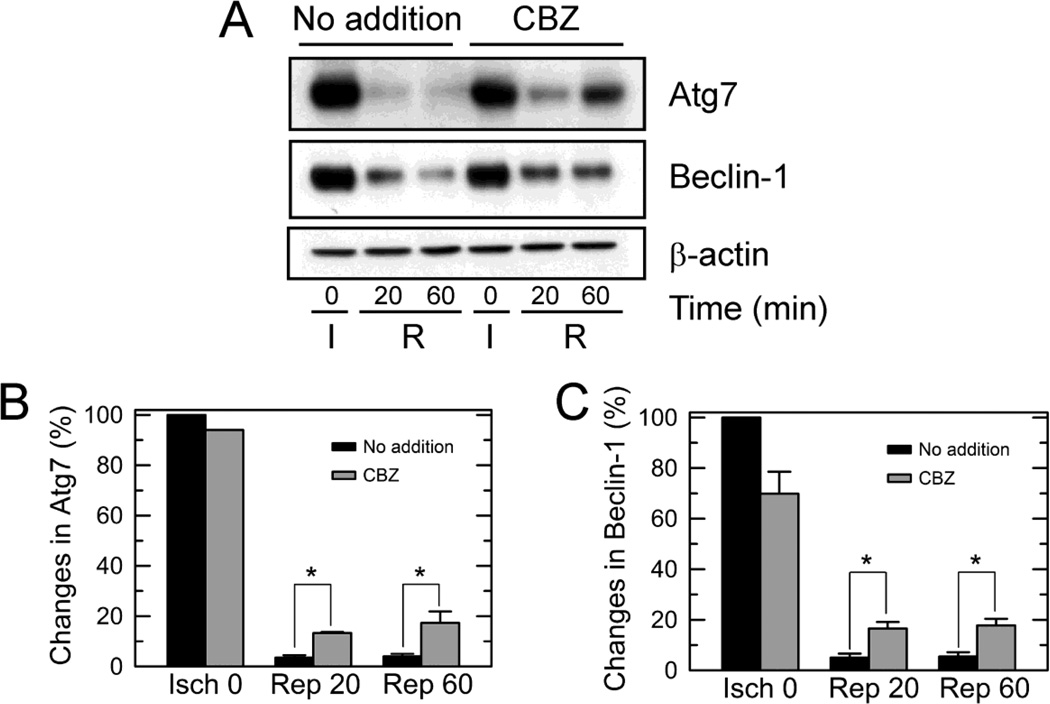

CBZ suppresses calpain-induced depletion of Atg7 and Beclin-1 after I/R

We next sought to identify the mechanisms underlying CBZ-mediated autophagy augmentation. Previously we showed that calpain-induced degradation of Atg7 and Beclin-1 leads to autophagy defects and MPT-dependent hepatocyte death after I/R (Kim et al., 2008). Accordingly, we performed immunoblotting analysis in the presence and absence of CBZ (Fig. 4). Consistent with a previous report (Kim et al., 2008), I/R in control hepatocytes drastically decreased the expression of both Atg7 and Beclin-1. However, CBZ significantly suppressed the loss of both proteins after reperfusion. The expression of Atg7 with CBZ was 380% and 433% higher than the expression without CBZ at 20 and 60 minutes after reperfusion, respectively (Fig. 4B). Likewise, the expression of Beclin-1 with CBZ was about 330% higher during reperfusion (Fig. 4C). Congruently, these results show that CBZ significantly thwarts reperfusion-induced loss of Atg7 and Beclin-1.

Fig. 4. Suppression of Atg7 and Beclin-1 loss by CBZ.

(A) Hepatocytes were exposed to 4 hours of ischemia (I), and changes in Atg7 and Beclin-1 following reperfusion (R) were determined by immunoblotting analysis. Expression of Atg7 (B) and Beclin-1 (C) was assessed relative to the level at 0 hour of ischemia (Isch). * P < 0.05.

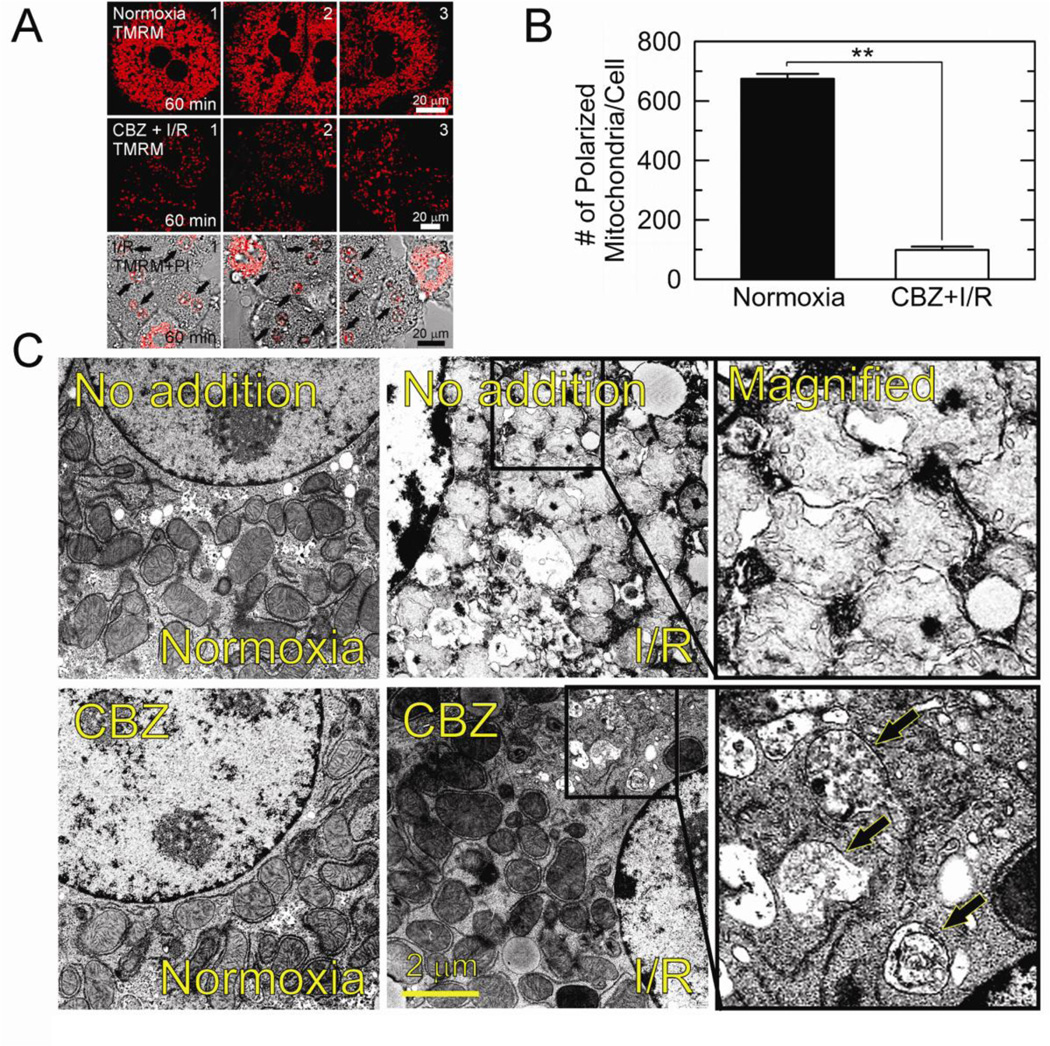

Mitophagy is an integral quality control mechanism that selectively eliminates damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria (Kim et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). Impaired mitophagy is the causative event leading to MPT onset and hepatocyte death after I/R (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). As CBZ suppressed autophagy defects (Fig. 2–4) and improved mitochondrial bioenergetics and cell viability after reperfusion (Fig. 1), cytoprotection by CBZ could result from its enhancement of mitophagy. To test this possibility, the number of polarized mitochondria in normoxic or reperfused hepatocytes was counted using confocal analysis with TMRM (Fig. 5A and B). After 60 minutes of normoxia, there were 660.7 ± 13.7 polarized mitochondria per cell (top panels), which was, however, significantly (p < 0.01) decreased to 106.3 ± 12.2 in CBZ-treated hepatocytes at 60 minutes after reperfusion (middle panels). In the absence of CBZ, most hepatocytes underwent necrosis at this time (arrows, bottom panels). As CBZ kept hepatocytes viable and blocked the MPT following reperfusion (Fig. 1), the decrease in polarized mitochondria in this circumstance was not a consequence cell death. Rather, these results suggest an induction of mitophagy by CBZ, leading to a robust clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria after reperfusion. CBZ-mediated induction of mitophagy was further confirmed with electron micrographs. As shown in Fig. 5C, the mitochondria of control cell after I/R were swollen and its cristae were barely distinguishable. On the other hand, CBZ-treated cells sustained the fine structure of cristae. Furthermore, the number of mitochondria was sparse, especially in perinuclear region where numerous autophagic vesicles were evident (arrows).

Fig. 5. Mitophagy onset by CBZ.

(A) Confocal images of TMRM from three different fields were collected at 60 minutes after normoxia (top panels) and after reperfusion (I/R) with (middle panels) and without CBZ (bottom panels). Note that 5 out of 6 cells were dead in the absence of CBZ, as judged by PI labeling in nuclei. (B) Changes in the number of polarized mitochondria at 60 minutes after normoxia and I/R. **P < 0.01. (C) Transmission electron micrographs were collected after 20 minutes of normoxia and reperfusion. Note the presence of autophagic vesicles (arrows) after reperfusion of CBZ-treated cells.

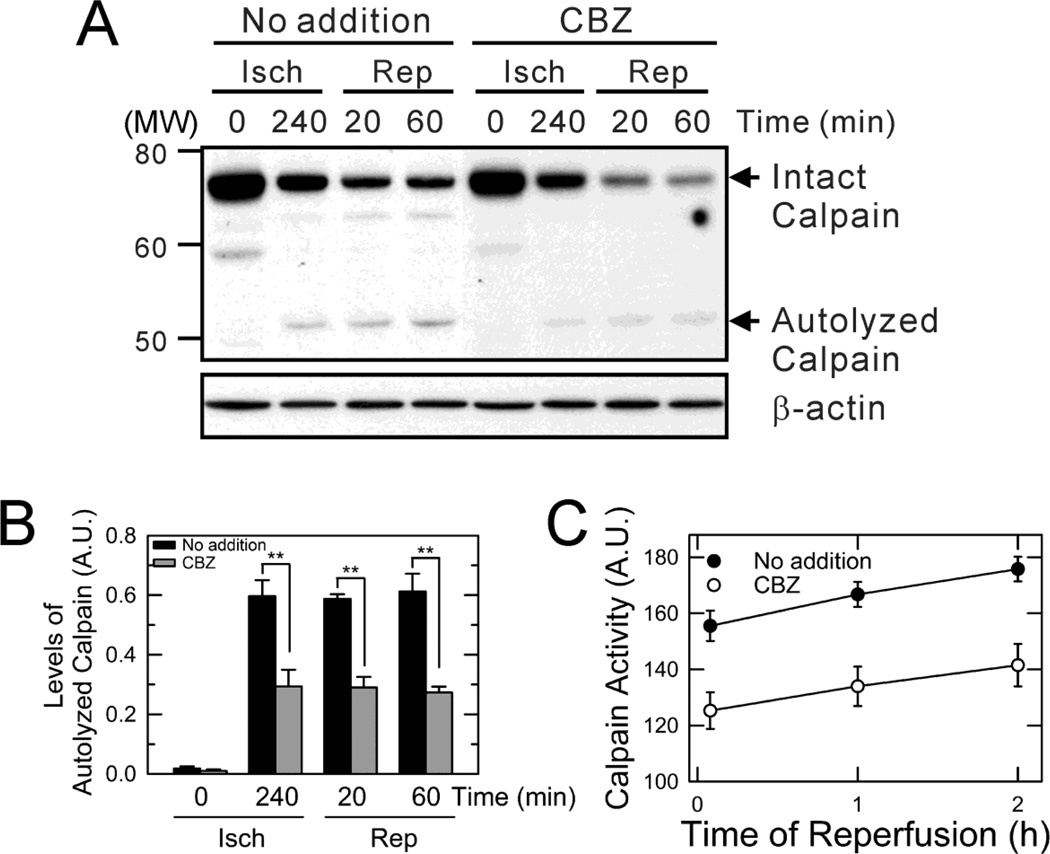

Calpains cause Atg loss after I/R (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011) and its inhibition induces autophagy (Williams et al., 2008). CBZ reduces cellular levels of inositol and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) by inhibiting inositol-1-phosphatae synthase (Williams et al., 2008; Fleming et al., 2011). As IP3 is a second messenger mobilizing Ca2+ from internal stores (Sarkar et al., 2005) and CBZ suppressed depletion of Atg after reperfusion (Fig. 4), we reasoned that CBZ could block reperfusion-induced calpain activation. To examine the effects of CBZ on calpains, calpain expression and activity were determined. Upon activation, calpains rapidly auto-hydrolyze the large subunit of enzymes (∼ 80-kDa) to several smaller fragments (18- to 54-kDa) (Chou et al., 2011). Thus, an increase in hydrolyzed fragments represents calpain activation. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that CBZ significantly, albeit not completely, blocked calpain activation at the end of ischemia and continuously after reperfusion (Fig. 6A and B). It is noteworthy that reperfusion decreased the levels of large subunit, which was further accelerated by CBZ. The decrease in both intact and autolyzed subunit suggests that CBZ not only stymies the autolytic conversion but modulates calpain precursors. To further confirm the inhibitory effect of CBZ on calpains, changes in calpain activity were fluorometrically determined using succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (SLLVY-AMC), a membrane permeable calpain substrate (Fig. 6C). Cleavage of the amide bond by calpains liberates a highly fluorescent AMC moiety (Kim et al., 2008). Similar to the immunoblotting analysis, CBZ markedly delayed calpain activation after reperfusion. Thus, these data indicate that CBZ suppresses the depletion of Atg7 and Beclin-1, at least in part, through blocking calpain activation after I/R.

Fig. 6. Suppression of calpain activation by CBZ.

(A) Hepatocyte lysates were collected at 0 and 240 minutes of ischemia (Isch) and at 20 and 60 minutes after reperfusion (Rep). Calpain activity was determined by immunoblotting in the presence and absence of CBZ. (B) Densitometrical analysis of autolyzed calpains. **P < 0.01. (C) Calpain activity was assessed by SLLVY-AMC fluorometry.

CBZ suppresses Ca2+ overloading after I/R

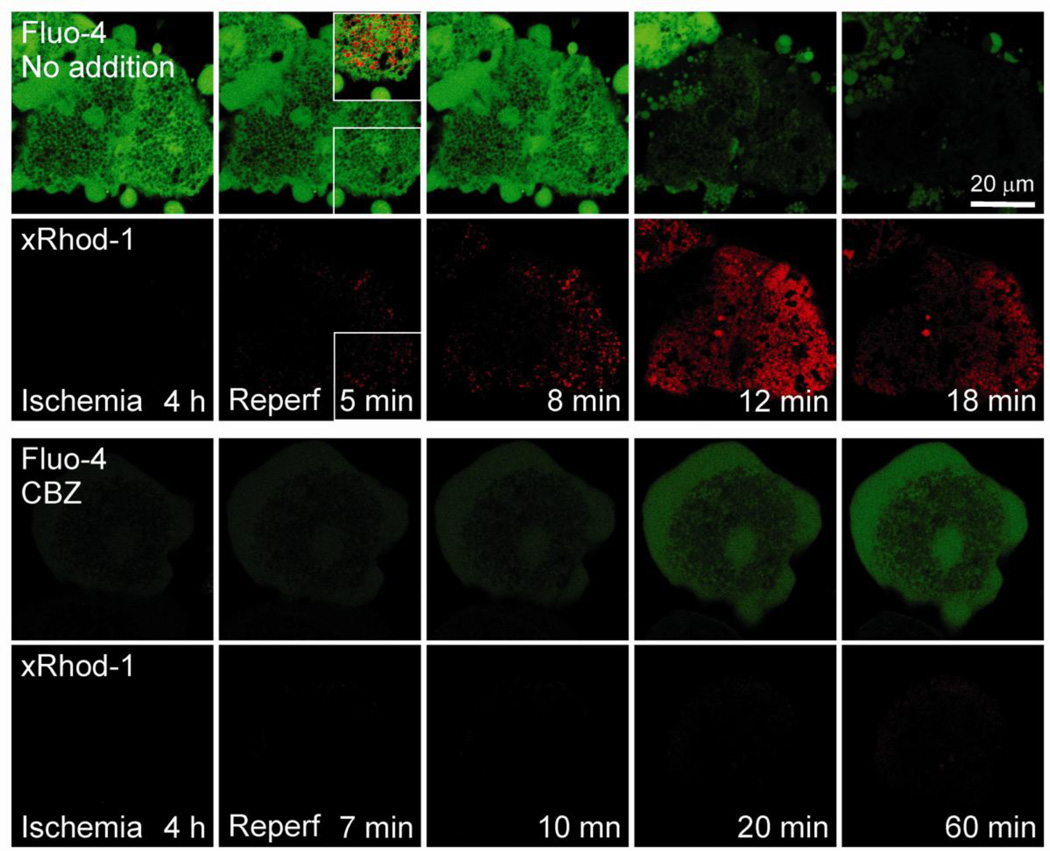

Calpains are Ca2+-dependent intracellular cysteine proteases. These enzymes are tightly regulated in normal cells, but an uncontrolled rise in Ca2+ levels can cause a continuous activation of calpains, leading to tissue injury (Goll et al., 2003). To examine whether CBZ influences Ca2+ perturbations after I/R, hepatocytes were co-loaded with xRhod-1 and Fluo-4 to evaluate mitochondrial and cytosolic Ca2+, respectively. After 4 hours of ischemia, the green fluorescence of Fluo-4 in control hepatocytes was evident except for the areas where dark voids localized near nuclei and plasma membranes (Fig. 7, top panels). In addition, numerous green fluorescing membrane blebs were noticeable, indicative of increased cytosol Ca2+ after ischemia. The red fluorescence of xRhod-1 was, however, barely detectable at this time, connoting minimal levels of mitochondrial Ca2+ during ischemia. After 5 minutes of reperfusion, the punctate mitochondrial xRhod-1 fluorescence increased by 290%, compared to the value at 4 hours of ischemia. On the other hand, the green fluorescence of Fluo-4 decreased by 11%, showing that reperfusion increases mainly mitochondrial Ca2+, but not cytosolic Ca2+. Furthermore, an overlay image of xRhod-1 and Fluo-4 fluorescence showed a co-localization of red puncta with dark voids in the green channel, confirming a selective labeling of xRhod-1 and Fluo-4 in the mitochondria and non-mitochondrial compartments, respectively (inset at 5 minutes of reperfusion). The mitochondrial Ca2+ overloading persisted for about 12 minutes and decreased later. The late decrease of xRhod-1 fluorescence likely represents mitochondrial Ca2+ release into the cytosol as a consequence of MPT onset and loss of the mitochondrial permeability barrier. On the other hand, the administration of CBZ strikingly reduced Ca2+ alterations during I/R (bottom panels). Plot analysis of Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity revealed that after 4 hours of ischemia, cytosolic Ca2+ was 80% lower in the CBZ group than the control group. Mitochondrial Ca2+ during ischemia was minimal in both the control and the CBZ group. In contrast to control cells, intramitochondrial Ca2+ overloading did not occur to CBZ-treated cells after reperfusion although both cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ slowly increased at the end of reperfusion. These results thus demonstrate that CBZ blocks Ca2+ overloading during I/R.

Fig. 7. Blockade of Ca2+ overloading by CBZ.

Confocal images of mitochondrial xRhod-1 (red) and cytosolic Fluo-4 (green) were simultaneously collected. Note a co-localization of red xRhod-1 puncta with dark voids in the green channel (inset of 5 minutes of reperfusion, top panels).

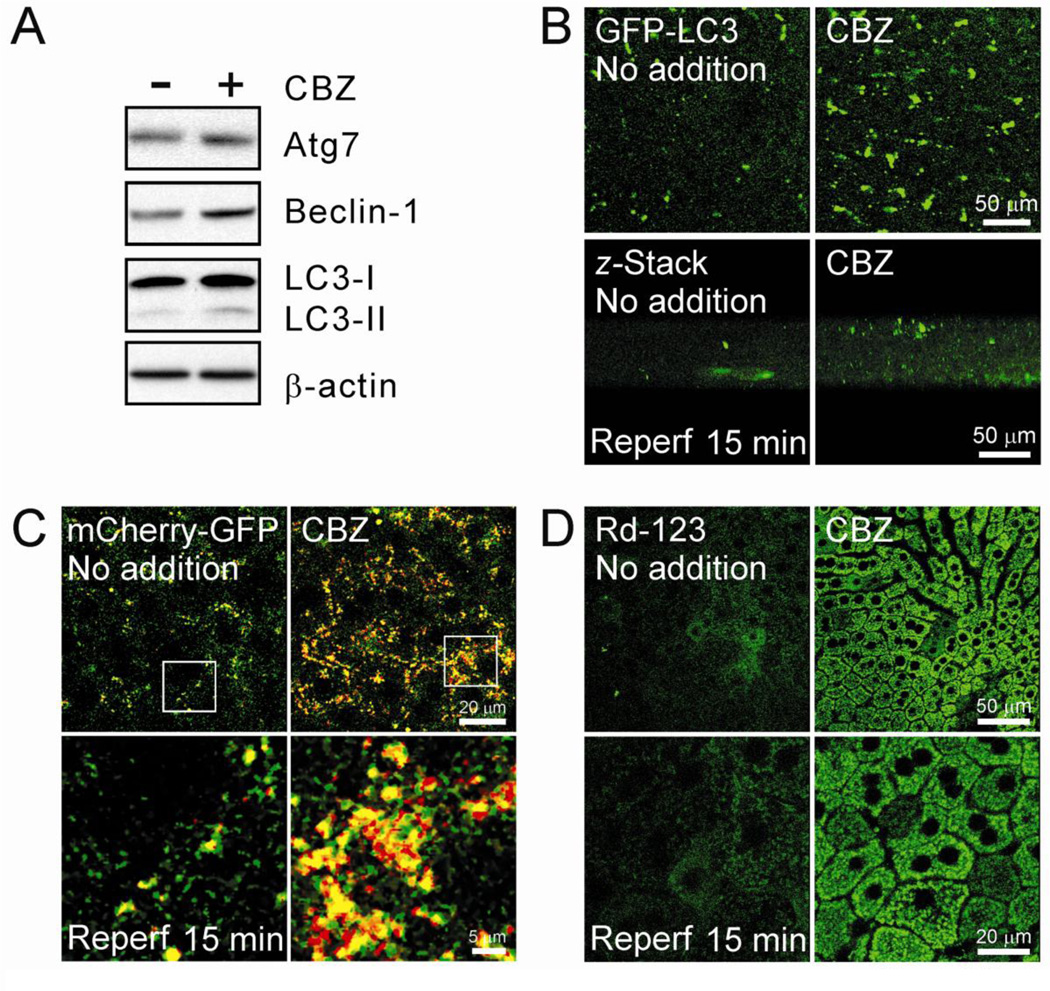

CBZ prevents autophagic defects and mitochondrial dysfunction after I/R in vivo

Zonal differences and cell-to-cell interactions within the liver are important parameters that determine the pathophysiology of in vivo I/R injury. To translate our findings from isolated hepatocytes into in vivo livers, livers were subjected to 45 minutes of in vivo ischemia by clamping the portal triad. Reperfusion was then initiated by releasing the clamp. Some animals were administered CBZ at a concentration of 25 mg/kg of body weight before ischemia. Immunoblotting analysis of autophagy proteins after 15 minutes of reperfusion showed that CBZ considerably increased the expression of Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3-II (Fig. 8A), similar to results from hepatocytes. Intravital multiphoton images of GFP-PC3 after I/R in vivo exhibited a substantial increase in autophagosome formation by CBZ (Fig. 8B). As autophagy is a dynamic process between autophagosome formation and autolysosomal clearance, increased LC3-II by CBZ could be due to either an increase in autophagosome formation or a decrease in autophagosomal clearance. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we simultaneously visualized autophagosomes and autolysosomes with mCherry-GFP-LC3. Multiphoton imaging with this tandem autophagy marker further revealed a substantial increase in both yellow and red puncta in CBZ-treated livers, signifying that livers with CBZ have both more autophagosomes and autolysosomes after I/R (Fig. 8C). Finally, we compared Δψm between control and CBZ-treated livers, using Rhodamine 123, a Δψm indicator (Wang et al., 2011). In control livers, most Rhodamine 123 fluorescence disappeared after reperfusion in vivo with some diffuse staining, indicating widespread mitochondrial depolarization and failure (Fig. 8D). In striking contrast, CBZ-treated livers displayed punctate, bright green fluorescence of Rhodamine 123 in hepatocytes, denoting polarized mitochondria after reperfusion. In agreement with results above, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and necrosis were also significantly lower in CBZ-treated mice after reperfusion, compared to untreated animals (Supplemental Fig. 2). Therefore, these in vivo results not only confirm our in vitro findings, but further support our conclusion that CBZ suppresses impaired autophagy after I/R, which, in turn, suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death.

Fig. 8. Cytoprotection by CBZ against I/R in vivo.

(A) After 45 minutes of ischemia in vivo, livers were exposed to 15 minutes of reperfusion. Some animals were treated with CBZ overnight prior to in vivo I/R. Tissue lysates were collected and immunoblotting analysis of Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3-I/II was performed. (B) Mice were injected with adenovirus expressing GFP-LC3 and intravital multiphoton images of autophagosomes were collected at 0.7-µm intervals after in vivo reperfusion. To visualize autophagosomes through the thickness (70 µm), z-stacks of GFP-LC3 fluorescence were collected. (C) Multiphoton images of mCherry-GFP-LC3 after 15 minters of reperfusion in vivo. Bottom panels represent magnified images of square insets at the top panels. (D) Livers were labeled with rhodamine 123 after in vivo I/R and multiphoton images of the mitochondria were collected. Punctate bright green fluorescence of rhodamine 123 represents polarized mitochondria. Bottom panels are in higher magnification.

Discussion

Autophagy plays a vital role under both normal and pathological conditions. In normal., unstressed conditions, autophagy primarily provides cells and tissues with nutrients. When cells are exposed to stresses such as I/R, alcohol or acetaminophen, autophagy becomes stimulated as an adaptive response to these stresses (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2010; Ni et al., 2012). As such, tissue injury ensues when autophagy becomes insufficient or impaired. In this study, we demonstrate that CBZ sequentially suppresses Ca2+ overloading, uncontrolled calpain activation, degradation of Atg7 and Beclin-1, defective autophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction after reperfusion. Furthermore, we show in I/R in vivo that CBZ substantially ameliorates the loss of autophagy proteins, impaired autophagic flux and mitochondrial dysfunction after reperfusion, suggesting a therapeutic potential of CBZ for attenuating I/R injury in livers.

CBZ prevented the MPT onset and necrotic cell death after simulated in vitro I/R (Fig. 1), confirming a causative role of the MPT in I/R injury to hepatocytes (Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). In accordance with a previous report (Kim et al., 2008), we here demonstrate that depletion of Atg7 and Beclin-1 is an event culminating in impaired autophagy after I/R (Fig. 4 and 8). The importance of these autophagy proteins has been well documented in various studies. For instance, in Atg7-deficient transgenic animals, mice accumulate abnormal mitochondria in livers (Komatsu et al., 2005). Beclin-1 deficiency is associated with reperfusion and other injury (Kim et al., 2008; Liang et al., 1999; Pickford et al., 2008).

As CBZ reduces reperfusion-induced cell death, increased autophagy by this agent could result from the difference of live cells between control and CBZ group. As a matter of fact, the difference of autophagic responsiveness between control and CBZ group may become more evident at the late phase of reperfusion since necrotic cell death of control cells increases progressively with reperfusion. However, fluorescence images of GFP-LC3 and PI at the earlier stages of reperfusion showed that the number of autophagosomes is substantially greater in CBZ-treated hepatocytes at these times (supplemental Fig. 1). Onset of the MPT was yet to occur before 5 minutes of reperfusion (Fig. 1) and cells in both groups remained viable (Qian et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2003c; Kim et al., 2012). Therefore, together with autophagic flux and imaging analysis, this result supports our conclusion that CBZ-treated hepatocytes have a higher autophagic activity and continue to clear damaged or abnormal mitochondria throughout 2 hours of reperfusion.

Calpains are multi-subunit, Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases and preferentially hydrolyze some autophagy proteins (Yousefi et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). The two most abundant isoforms in nearly all tissues are calpain 1 (µ-isoform) and calpain 2 (m-isoform) that have different Ca2+ requirements for their activation. An uncontrolled rise in Ca2+ due to energy depletion and/or dysfunctional Ca2+ pumps can cause a prolonged and deregulated activation of calpains, leading to tissue injury. We have shown that activation of calpains, especially the calpain 2 isoform, is directly associated with autophagy defects after I/R (Kim et al., 2008;Wang et al., 2011). Our results show that CBZ blocks calpain activation and depletion of autophagy proteins after reperfusion (Fig. 4 and 6), substantiating a crucial role of calpain activation in the depletion of Atg7 and Beclin-1 after reperfusion. In livers, inhibition of calpains improves hepatic viability and function after I/R (Kim et al., 2008;Wang et al., 2011; Kohli et al., 1999). Pharmacological inhibition of calpains and knockdown of either calpain 1 or 2 have recently been shown to induce autophagy by an mTOR-independent manner (Williams et. al., 2008; Kuro et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2010) and confer cytoprotection against I/R damage in retina (Russo et al., 2011) and heart (Pedrozo et al., 2010).

While a growing body of evidence indicates adverse effects of calpains on autophagy, the necessity of calpains in autophagy execution has been proposed as well (Demarchi et al., 2006). Calpains have long been somewhat misrepresented as an injurious or degradative enzyme. In normal cells, these Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases are indispensable for diverse physiological functions including cytoskeletal remodeling, cell motility and gene regulation (Goll et al., 2003). Mice lacking calpains are embryonically lethal (Arthur et al., 2000). Hence, calpains may modulate autophagy under normal., unstressed conditions. However, an uncontrolled activation of calpains under pathological conditions assuredly results in unwanted cleavage of essential proteins, causing irreversible tissue damage. Calpain-mediated hydrolysis of Beclin-1 under stressed environment has been reported in liver (Kim et al., 2008), retina (Russo et al., 2011), and nerve tissues (Song et al., 2012). Of note, we found that CBZ alone failed to fully recover Atg7 and Beclin-1 expression to the normoxic values. This could result from a partial inhibition of calpains by CBZ, as shown in Fig. 6. Another possibility is that factors other than calpains may participate in the loss of autophagy proteins in I/R. Identification of these factors warrants future investigation.

Although CBZ markedly suppressed cell death, the levels of Atg7 and Beclin-1 after reperfusion with this agent were about 20% of control values (Fig. 4). The minimal levels of Atg needed for adequate response to stresses are unknown. However, we have shown in rat hepatocytes that 15–20% recovery of Atg by genetic or pharmacological strategy can block MPT onset and cell death after I/R (Kim et al., 2008). During an acute injury like I/R, discrete mitochondrial pool appears to be more susceptible to reperfusion insult since widespread MPT is preceded by the initial MPT onset to a few mitochondria (Wang et al., 2011). The importance of initial MPT induction in subsequently extensive mitochondrial dysfunction has been well documented (Hajnoczky et al., 1995; Pacher et al., 2001; Goldstein et al., 2000). Hence, timely clearance of these PR-prone mitochondria by mitophagy may be sufficient to attenuate signal propagation to adjacent mitochondria and ultimately global MPT onset. Moreover, it has been demonstrated in Atg7 transgenic mice that heterozygous animals (Atg7 +/−), wherein Atg7 is diminished by 80%, show normal phenotypes, whereas knockout animals (Atg 7 −/−) die a day after birth with a severe mitochondrial abnormality (Komatsu et al., 2005). Similarly, embryonic lethality is observed only in Beclin-1 null animals, but not heterozygous mutant animals (Yue et al., 2003).

CBZ decreases intracellular Ca2+ by inhibiting inositol synthesis and reducing IP3, a second messenger mobilizing Ca2+ from internal stores (Sarkar et al., 2005). We here showed that CBZ prevents Ca2+ overloading after I/R (Fig. 7), further supporting our conclusion that calpains contribute to I/R injury. Confocal imaging revealed distinct perturbations in Ca2+ during I/R: while cytosolic Ca2+ increases during ischemia with little or no change in mitochondrial Ca2+, mitochondrial Ca2+ increases nearly exclusively after reperfusion, consistent with our recent report (Kim et al., 2012). The increase in cytosolic Ca2+ during ischemia may be a consequence of a collapse of Na+ and K+ gradients and inhibition of ATP-driven Ca2+ pumps. Moreover, mitochondrial depolarization during ischemia blocks the Δψm-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (Kim et al., 2012). A causal role of Ca2+ overloading in the MPT onset is well corroborated in isolated mitochondria (Crompton et al., 1988) and in hepatocytes (Kim et al., 2012; Byrne et al., 1999). Interestingly, suppression of extramitochondrial Ca2+ by CBZ also accompanied a marked reduction of intramitochondrial Ca2+ after reperfusion, suggesting that mitochondrial Ca2+ overloading during reperfusion may be, at least in part, commenced by elevated extramitochondrial Ca2+ after ischemia. Since the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is electrogenic, transient repolarization of the mitochondria during the early stage of reperfusion could emanate a massive entry of Ca2+ into the mitochondria. Henceforth, Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondria far exceeds mitochondrial capacity for Ca2+ efflux, Δψm becomes collapsed, and the electron transport chain becomes uncoupled from ATP synthesis later. Future studies are required to delineate how Ca2+ translocation between different compartments is affected by I/R.

Our results show that autophagy is negatively impacted by high levels of Ca2+. However, there exist ongoing debates as to whether Ca2+ prevents or promotes autophagy. Ca2+ can enhance autophagy in moderately stressed cells (Decuypere et al., 2011). Taking account of a pro-survival role of autophagy, autophagy induction by Ca2+ under mild stress may represent an intrinsic adaptation of cells to stress. As autophagy is an energy-consuming process, ATP-loaded healthy cells are capable of coping with stress through active autophagy. However, ATP-deficient cells such as reperfused hepatocytes have a limited capacity for autophagy. As a consequence, the extent of stress exceeds the eventual autophagic capacity and cell death ensues thereafter. In line with this view, we repeatedly observed a transient increase in autophagy during the early phase of reperfusion when mitochondrial Ca2+ begins to arise. Nonetheless, autophagy induction was temporary, and cells underwent mitochondrial dysfunction, ATP depletion and ultimately cell death during the late phase of reperfusion. A continuous rise in Ca2+ is likely to instigate uncontrolled activation of calpains, which, in turn, results in the unwanted cleavage of key autophagy proteins, autophagy defects and cell death after PR.

In conclusion, CBZ protects hepatocytes against I/R injury by preventing a temporal sequence of calcium overloading, calpain activation, Atg7 and Beclin-1 depletion, defective autophagy, onset of the MPT and cell death. CBZ is an FDA- approved, pro-autophagy agent that can potentially be an alternative to gene therapy. Enhancing autophagy by CBZ could be a new strategy to improve liver function after I/R injury.

Supplementary Material

Hepatocytes infected with adenovirus harboring GFP-LC3 were subjected to I/R in the presence of PI. Confocal images of green (autophagosomes, yellow arrows) and red (necrosis, white arrows) fluorescence were acquired at 3, 15 and 30 minutes after reperfusion with and without CBZ. At 3 and 15 minutes, control cells were viable but had substantially fewer autophagosomes than CBZ-treated cells.

(A) Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were colorimetrically measured with a commercial kit (Biovision, Milpitas, California) after 60 minutes of reperfusion. * P < 0.05. (B) Liver tissues were fixed, embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) after 60 minutes of reperfusion.

Highlights.

A mechanism of carbamazepine (CBZ)-induced cytoprotection in livers is proposed.

Impaired autophagy is a key event contributing to lethal reperfusion injury.

The importance of autophagy is extended and confirmed in an in vivo model.

CBZ is a potential agent to improve liver function after liver surgery.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by US National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK079879 and DK090115 (J-S Kim) and National Institute on Aging AG028740 (J-S Kim).

List of Abbreviations

- MPT

mitochondrial permeability transition

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- CBZ

carbamazepine

- FDA

Food & Drug Administration

- Atg

autophagy-related proteins

- KRH

Krebs-Ringer-N-2 hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2 ethanesulfonic acid

- PI

propidium iodide

- TMRM

tetramethylrhodamine methylester

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

- CQ

chloroquine

- IP3

inositol-l,4,5-triphosphate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jae-Sung Kim, Email: Jae.Kim@surgery.ufl.edu.

Jin-Hee Wang, Email: jin-hee.wang@surgery.ufl.edu.

Thomas G Biel, Email: Thomas.Biel@surgery.ufl.edu.

Do-Sung Kim, Email: do-sung.kim@surgery.med.ufl.edu.

Joseph A. Flores-Toro, Email: Joseph.Flores-Toro@surgery.ufl.edu.

Richa Vijayvargiya, Email: rvijayvargiya@ufl.edu.

Ivan Zendejas, Email: ivan.zendejas@surgery.ufl.edu.

Kevin E. Behrns, Email: Kevin.Behrns@surgery.ufl.edu.

References

- 1.Arthur JS, Elce JS, Hegadorn C, Williams K, Greer PA. Disruption of the murine calpain small subunit gene, Capn4: calpain is essential for embryonic development but not for cell growth and division. Mol.Cell Biol. 2000;20:4474–4481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4474-4481.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brattstrom C, Wilczek HE, Tyden G, Bottiger Y, Sawe J, Groth CG. Hypertriglyceridemia in renal transplant recipients treated with sirolimus. Transplant.Proc. 1998;30:3950–3951. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne AM, Lemasters JJ, Nieminen AL. Contribution of increased mitochondrial free Ca2+ to the mitochondrial permeability transition induced by tert-butylhydroperoxide in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1999;29:1523–1531. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou JS, Impens F, Gevaert K, Davies PL. m-Calpain activation in vitro does not require autolysis or subunit dissociation. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2011;1814:864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crompton M, Ellinger H, Costi A. Inhibition by cyclosporin A of a Ca2+-dependent pore in heart mitochondria activated by inorganic phosphate and oxidative stress. Biochem.J. 1988;255:357–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca2+ in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demarchi F, Bertoli C, Copetti T, Tanida I, Brancolini C, Eskelinen EL, Schneider C. Calpain is required for macroautophagy in mammalian cells. J.Cell Biol. 2006;175:595–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding WX, Li M, Chen X, Ni HM, Lin CW, Gao W, Lu B, Stolz DB, Clemens DL, Yin XM. Autophagy Reduces Acute Ethanol-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Steatosis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1740–1752. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn WA., Jr Studies on the mechanisms of autophagy: maturation of the autophagic vacuole. J.Cell Biol. 1990;110:1935–1945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nat.Chem.Biol. 2011;7:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerencser AA AA, Adam-Vizi V. Selective, high-resolution fluorescence imaging of mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration. Cell Calcium. 2001;30:311–321. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein JC, Waterhouse NJ, Juin P, Evan GI, Green DR. The coordinate release of cytochrome c during apoptosis is rapid, complete and kinetically invariant. Nat.Cell Biol. 2000;2:156–162. doi: 10.1038/35004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell. 1995;82:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartford CM, Ratain MJ. Rapamycin: something old, something new, sometimes borrowed and now renewed. Clin.Pharmacol.Ther. 2007;82:381–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim I, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Lemasters JJ. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 2007;462:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J-S, Nitta T, Mohuczy D, O'Malley KA, Moldawer LL, Dunn WA, Jr, Behrns KE. Impaired autophagy: A mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in anoxic rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;47:1725–1736. doi: 10.1002/hep.22187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J-S, Qian T, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in the switch from necrotic to apoptotic cell death in ischemic rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2003a;124:494–503. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J-S, He L, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition: a common pathway to necrosis and apoptosis. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2003b;304:463–470. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J-S, He L, Qian T, Lemasters JJ. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition in apoptotic and necrotic death after ischemia/reperfusion injury to hepatocytes. Curr.Mol.Med. 2003c;3:527–535. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J-S, Jin Y, Lemasters JJ. Reactive oxygen species, but not Ca2+ overloading, trigger pH- and mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent death of adult rat myocytes after ischemia/reperfusion. Am.J.Physiol Heart Circ.Physiol. 2006;290:H2024–H2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00683.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J-S, Wang JH, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in rat hepatocytes after anoxia/reoxygenation: Role of Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. Am.J.Physiol Gastrointest.Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G723–G731. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00082.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohli V, Madden JF, Bentley RC, Clavien PA. Calpain mediates ischemic injury of the liver through modulation of apoptosis and necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:168–178. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J.Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuro M, Yoshizawa K, Uehara N, Miki H, Takahashi K, Tsubura A. Calpain inhibition restores basal autophagy and suppresses MNU-induced photoreceptor cell death in mice. In Vivo. 2011;25:617–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni HM, Bockus A, Boggess N, Jaeschke H, Ding WX. Activation of autophagy protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2012;55:222–232. doi: 10.1002/hep.24690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieminen AL, Gores GJ, Bond JM, Imberti R, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. A novel cytotoxicity screening assay using a multiwell fluorescence scanner. Toxicol.Appl.Pharmacol. 1992;115:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90317-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pacher P, Hajnoczky G. Propagation of the apoptotic signal by mitochondrial waves. EMBO J. 2001;20:4107–4121. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedrozo Z, Sanchez G, Torrealba N, Valenzuela R, Fernandez C, Hidalgo C, Lavandero S, Donoso P. Calpains and proteasomes mediate degradation of ryanodine receptors in a model of cardiac ischemic reperfusion. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2010;1802:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickford F, Masliah E, Britschgi M, Lucin K, Narasimhan R, Jaeger PA, Small S, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Levine B, Wyss-Coray T. The autophagy-related protein beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid beta accumulation in mice. J.Clin.Invest. 2008;118:2190–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI33585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian T, Nieminen AL, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in pH-dependent reperfusion injury to rat hepatocytes. Am.J.Physiol. 1997;273:C1783–C1792. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo R, Berliocchi L, Adornetto A, Varano GP, Cavaliere F, Nucci C, Rotiroti D, Morrone LA, Bagetta G, Corasaniti MT. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 and autophagy deregulation following retinal ischemic injury in vivo. Cell Death.Dis. 2011;2:e144. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarkar S, Floto RA, Berger Z, Imarisio S, Cordenier A, Pasco M, Cook LJ, Rubinsztein DC. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J.Cell Biol. 2005;170:1101–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song F, Han X, Zeng T, Zhang C, Zou C, Xie K. Changes in beclin-1 and micro-calpain expression in tri-ortho-cresyl phosphate-induced delayed neuropathy. Toxicol.Lett. 2012;210:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verma IM, Somia N. Gene therapy -- promises, problems and prospects. Nature. 1997;389:239–242. doi: 10.1038/38410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JH, Ahn IS, Fischer TD, Byeon JI, Dunn WA, Jr, Behrns KE, Leeuwenburgh C, Kim J-S. Autophagy Suppresses Age-Dependent Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury in Livers of Mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2188–2199. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams A, Sarkar S, Cuddon P, Ttofi EK, Saiki S, Siddiqi FH, Jahreiss L, Fleming A, Pask D, Goldsmith P, O'Kane CJ, Floto RA, Rubinsztein DC. Novel targets for Huntington's disease in an mTOR-independent autophagy pathway. Nat.Chem.Biol. 2008;4:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia HG, Zhang L, Chen G, Zhang T, Liu J, Jin M, Ma X, Ma D, Yuan J. Control of basal autophagy by calpain1 mediated cleavage of ATG5. Autophagy. 2010;6:61–66. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death.Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, Ziemiecki A, Schaffner T, Scapozza L, Brunner T, Simon HU. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat.Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2003;100:15077–15082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hepatocytes infected with adenovirus harboring GFP-LC3 were subjected to I/R in the presence of PI. Confocal images of green (autophagosomes, yellow arrows) and red (necrosis, white arrows) fluorescence were acquired at 3, 15 and 30 minutes after reperfusion with and without CBZ. At 3 and 15 minutes, control cells were viable but had substantially fewer autophagosomes than CBZ-treated cells.

(A) Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were colorimetrically measured with a commercial kit (Biovision, Milpitas, California) after 60 minutes of reperfusion. * P < 0.05. (B) Liver tissues were fixed, embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) after 60 minutes of reperfusion.