Abstract

Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (neem, family: Meliaceae) is perhaps the most commonly used traditional medicinal plant of India. In this study we investigated the protective effect of methanolic neem leaves extract (MNLE; 500 mg/Kg bwt) on rats treated with cisplatin (CDDP)-induced hepatotoxicity. Adult rats were randomly divided into four groups. CDDP was given to rats by intraperitoneal injection, while MNLE was given by oral gavage for 5 days after the CDDP injection. The injury and oxidative stress caused by CDDP on the liver and the effect of MNLE were evaluated by measuring (a) histological changes, (b) tissue biochemical oxidant and antioxidant parameters, and (c) investigating apoptosis markers immunohistochemically and by real time PCR. After treatment with MNLE, the histological damage and apoptosis induction caused by cisplatin were improved. Malondialdehyde and nitric oxide were significantly decreased; the antioxidant system, namely, glutathione content, glutathione-S-transferase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase activities were significantly elevated. In conclusion, MNLE may have a potential role when combined with cisplatin in chemotherapy to alleviate cisplatin-induced damage and oxidative stress in liver.

1. Introduction

Cisplatin, cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (CDDP), with the molecular formula cis-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2], is one of the most remarkable platinum-based drug used in “the war on cancer” [1–3]. CDDP and related platinum-based therapeutics are being used for the treatment of testicular, head and neck, ovarian, cervical, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma, and many other types of cancer. Its use is mainly limited by two factors: acquired resistance to CDDP and severe side effects in normal tissues [4].

The side effects induced by CDDP include neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, nausea and vomiting, and nephrotoxicity. During the aggressive treatment protocols, higher doses of CDDP that may be required for effective tumor suppression could also lead to hepatotoxicity, which is also encountered during low-dose repeated CDDP therapy [5].

The liver is highly susceptible to oxidative reactions as it is the main center of metabolism of most of the substances in the body, including exogenous substances like drugs. Usually nephrotoxicity is monitored during treatment with CDDP, but hepatotoxicity does not receive much attention [6]. It has been reported that oxidative stress through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) decreased antioxidant defense systems, including antioxidant enzymes and nonenzymatic molecule glutathione (GSH), which are all major aspects of CDDP toxicity [7, 8].

In addition, functional and structural mitochondrial damage, apoptosis, perturbation in Ca2+ homeostasis, and involvement of proinflammatory genes such as COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) may play some important roles in the mechanism of CDDP hepatotoxicity [9].

Neem tree (Azadirachta indica) is one of the most widely used medicinal plants in the world [10] and has been for many years. The importance of the neem tree has been recognized by the US National Academy of Sciences. It published a report in 1992 entitled, “Neem—a tree for solving global problem” [11]. Biswas et al. [12] have reviewed the biological activities of some of the neem compounds, pharmacological actions of the neem extracts, clinical study, and plausible medicinal applications of neem along with their safety evaluation.

The leaves of the neem tree are traditionally used as medicinal preparations for their immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, antiulcer, antimalarial, antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, antimutagenic, and anticarcinogenic properties [13]. We aimed in this work to evaluate the hepatoprotective efficacy of a natural product, neem, against CDDP-induced hepatotoxicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Cisplatin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Perchloric acid, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) were purchased from Merck. All other chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. Double-distilled water was used as the solvent.

2.2. Preparation of Neem Leaves Extract

Fresh matured leaves of neem tree were collected from a garden in Obour City, Cairo, on August 2011. The samples were identified in Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Helwan University. The leaves were cleaned, dried, and powdered. Powder (100 g) of A. indica leaves was then consecutively macerated for one day in petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, chloroform, and methanol, respectively. On the basis of the preliminary phytochemicals tests conducted, the methanol extract was found to be rich in terms of chemical constituents, and therefore was selected for the experiment. The methanol was removed under reduced pressure to obtain a semisolid mass of methanolic neem leaves extract (MNLE). The MNLE was then stored in −20°C until used.

2.3. Animals and Experimental Design

Adult females of Wister albino rats weighing 150–180 g were obtained from The Holding Company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA, Cairo, Egypt). Rats were provided with water and balanced diet ad libitum. The experiments were approved by the state authorities following the Egyptian rules on animal protection. Twenty-four adult rats were randomly divided into four groups, six rats per group. Group I (Con group) served as untreated control. Group II (CDDP group) received a single intraperitoneal injection of CDDP (5 mg/kg, Sigma) and left for 5 days. Group III (MNLE group) received an oral administration of 500 mg/kg MNLE for 5 days via epigastric tube. Group IV (CDDP-N group) received the same dose of the extract for 5 days after a single intraperitoneal injection of CDDP (5 mg/kg). The animals of all groups were sacrificed by fast decapitation; blood samples were collected, allowed to stand for half an hour, and then centrifuged at 500 g for 15 min at 4°C to separate serum and stored at −70°C for the different biochemical measurements. The liver was dissected out. Part of the liver tissue was fixed immediately in 10% phosphate buffered formaldehyde for histological and immunohistochemical studies. Another part was weighed and homogenized immediately to give 50% (w/v) homogenate in ice-cold medium containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, and pH 7.4, then centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for the various biochemical determinations.

2.4. Liver Function Tests

Colorimetric determination of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was estimated by measuring the amount of pyruvate or oxaloacetate produced by forming 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine according to the method of Reitman and Frankel [14]. The color of which was measured spectrophotometerically at 546 nm. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (γGT) and alkaline phosphatase were assayed in liver homogenate using kits provided by Biodiagnostic Co. (Giza, Egypt), according to the method described by Szasz [15] and Belfield and Goldberg [16], respectively. Also, total bilirubin (TB) in serum was assayed according to the method of King and Coxon [17].

2.5. Oxidative Stress Markers

Homogenates of liver were used to determine lipid peroxidation (LPO) by reaction of thiobarbituric acid [18]. Similarly, those homogenates were used to determine nitrite/nitrate (nitric oxide; NO) [19] and glutathione (GSH) [20].

2.6. Enzymatic Antioxidant Status

The same homogenates of liver were used in determination of superoxide dismutase (SOD) [21], catalase (CAT) [22], glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [23], and glutathione reductase (GR) [24] activities.

2.7. Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the liver tissue using an RNeasy Plus Minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). One microgram total RNA and random primers were used for cDNA synthesis using the RevertAid H Minus Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Canada). For real time PCR analysis, the cDNA samples are run in triplicate and β-actin is used as reference gene. Each PCR amplification includes nontemplate controls containing all reagents except cDNA. Real time PCR reactions were performed using Power SYBR Green (Life Technologies, CA) and was conducted on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Instrument. The typical thermal profile is 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 56°C for 30 s. After PCR amplification, the ΔCt is calculated by subtraction of the β-actin Ct from each sample Ct. The method of Pfaffl was used for data analysis. The PCR primers for Bax and caspase-3 and 9 genes were synthesized by Jena Bioscience GmbH (Jena, Germany). Primers were designed using Primer-Blast program from NCBI. The PCR primer sequences are BLAST, searched to ensure for specificity to this particular gene. For a reference gene, the β-actin is used. The primer sets used were rat caspase-3 (forward: GCATGATCCGCGACGTGGAA; reverse: AGATCCATGCCGTTGGCCAG), caspase-9 (forward: ATGCAGGTCCCTGTCATG; reverse: GCTTGAGGTGGTTGTGGA), Bax (forward: AGATCACATTCACGGTGCTG; reverse: CTTCAGAGGCAGGAAACAGG), and β-actin (forward primer: AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC; reverse: CAATAGT GATGACCTGGCCGT).

2.8. Histopathological Examination

Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral formalin for 24 hours, and paraffin blocks were obtained and routinely processed for light microscopy. Slices of 4-5 μm were obtained from the prepared blocks and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The preparations obtained were visualized using a Nikon microscopy at a magnification of 400x.

2.9. Immunohistochemistry for Detection of NF-κB

For immunohistochemistry, liver sections (4 μm) were deparaffinized and then boiled to unmask antigen sites; the endogenous activity of peroxidase was quenched with 0.03% H2O2 in absolute methanol. Liver sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1 : 200 dilution of mouse NF-κB antibodies (Santa Cruz CA, USA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After removal of the unbound primary antibodies by rinsing with PBS, slides were incubated with a 1 : 500 dilution of biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were detected with avidin biotinylated peroxidase complex ABC-kit Vectastain, and the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB) is used as substrate. After appropriate washing in PBS, slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. All sections were incubated under the same conditions with the same concentration of antibodies and at the same time; so the immunostaining was comparable among the different experimental groups.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Differences between obtained values (means ± SEM, n = 6) were carried out by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Duncan test. A P value of 0.05 or less was taken as a criterion for a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

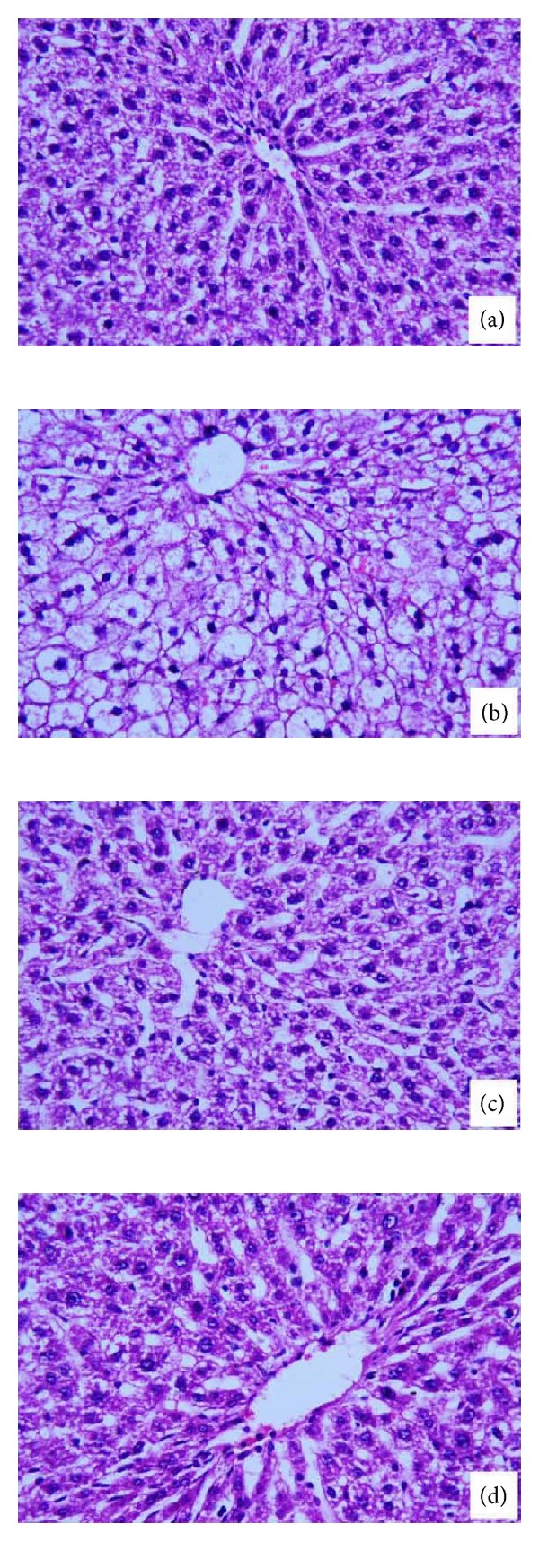

Normal control animals have revealed clear cut hepatic lobules separated by interlobular septa, transversed by portal vein (Figure 1(a)). The CDDP-induced hepatic damage is characterized by dispersed areas of necrotic hepatocytes, inflammatory cellular infiltration cytoplasmic vacuolation, and degeneration of hepatocytes (Figure 1(b)). Treatment of rats with MNLE largely prevented CDDP-induced histopathological changes in the liver as indicated by a reduction in inflammatory cellular infiltration and hepatocytic damages (Figure 1(d)). These histological abnormalities is coincide with a significant increase in activity of ALT, AST, γGT, ALP, and TB levels (Table 1), while treatment with MNLE significantly restored these levels to normal values (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Histological changes in the liver of rats. (a) A control liver with normal architecture. (b) Rats treated with cisplatin with prominent inflammation and hepatocytic vacuolation. (c) Rats treated with the neem leaves extract for 5 days. (d) Rats treated with the cisplatin and neem leaves extract. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (400x).

Table 1.

Protective effects of methanolic neem leaves extract on cisplatin (CDDP) induced alternation in liver function of rats.

| Groups | ALT (IU/L) | AST (IU/L) | γGT activity (IU/L) | ALP (IU/L) | Total bilirubin (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | 85.23 ± 3.98 | 68.98 ± 1.90 | 31.66 ± 1.15 | 4.26 ± 0.38 | 2.78 ± 0.16 |

| CDDP | 121.82 ± 3.13a | 90.32 ± 1.19a | 54.22 ± 1.88a | 6.82 ± 0.30a | 5.87 ± 0.20a |

| MNLE | 83.59 ± 1.23 | 72.09 ± 2.90 | 29.60 ± 1.24 | 3.84 ± 0.28 | 2.57 ± 0.08 |

| CDDP-N | 86.28 ± 1.91b | 70.88 ± 1.67b | 36.33 ± 1.37b | 4.99 ± 0.25b | 3.13 ± 0.22b |

Values are means ± SEM (n = 6).

a P < 0.05, significant change with respect to Control; b P < 0.05, significant change with respect to CDDP for Duncan's post hoc test.

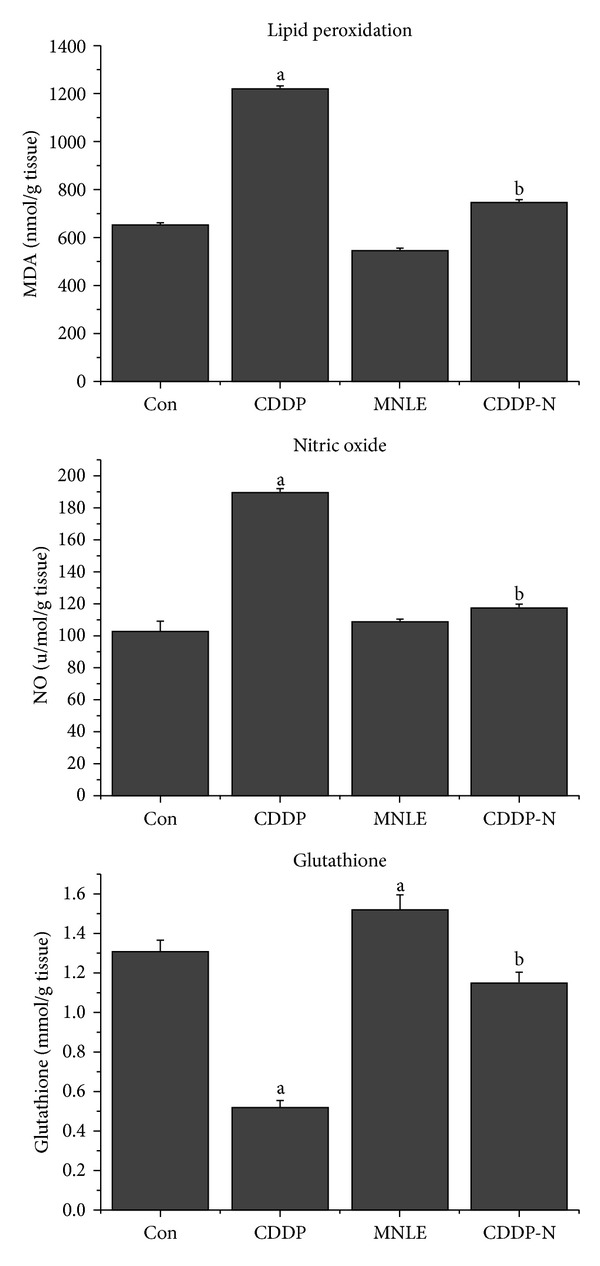

The CDDP-induced hepatic oxidant stress was evident by increased lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide and decreased GSH content as shown in (Figure 2). The LPO and NO levels in the liver of animals that administered CDDP alone were observed to display an increase compared with control group, and this increase was found to be statistically significant. The production of these markers is used as a biomarker to measure the level of oxidative stress in an organism [25]. This increase was attenuated by treatment with MNLE.

Figure 2.

Protective effects of neem leaves extract on cisplatin-induced elevation in lipid peroxidation, nitric oxide levels, and reduction in glutathione level in liver of rats. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). a P < 0.05, significant change with respect to Control; b P < 0.05, significant change with respect to CDDP group.

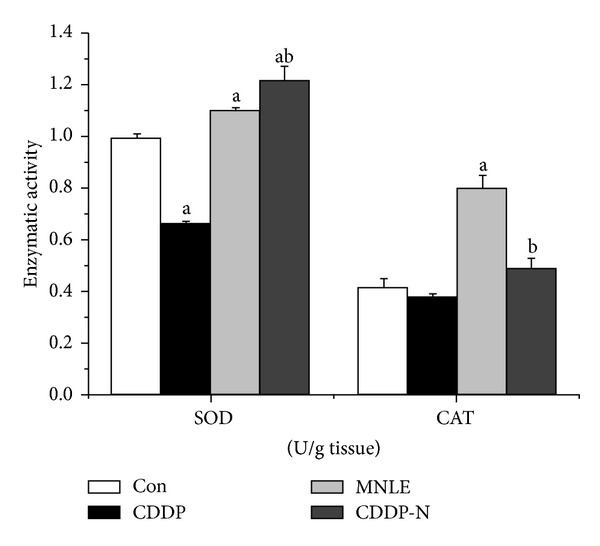

Also significantly reduced activities of the antioxidant enzymes GPx, GST, GR, CAT, and SOD were seen in the liver tissues of CDDP-treated rats compared with the control group. Treatment of rats with MNLE significantly alleviated these CDDP-induced decreases (Table 2, Figure 3) with a significant increase in GSH levels.

Table 2.

Protective effects of methanolic neem leaves extract on cisplatin (CDDP) induced alternation in enzymatic antioxidant molecules of rats.

| Groups | GR (μmol/hr/g tissue) | GST (μmol/hr/g tissue) | GPx (U/g tissue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Con | 93.77 ± 8.47 | 0.029 ± 0.006 | 567.39 ± 34.86 |

| CDDP | 73.11 ± 3.18a | 0.018 ± 0.003a | 313.41 ± 28.39a |

| MNLE | 184.20 ± 7.44a | 0.030 ± 0.001 | 459.61 ± 30.88a |

| CDDPN | 138.66 ± 4.73ab | 0.049 ± 0.004ab | 1350.93 ± 60.83ab |

Values are means ± SEM (n = 6).

a P < 0.05, significant change with respect to Control; b P < 0.05, significant change with respect to CDDP for Duncan's post hoc test.

Figure 3.

Protective effects of neem leaves extract on cisplatin-induced reduction in superoxide dismutase and catalase activities in liver of rats. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). a P < 0.05, significant change with respect to Control; b P < 0.05, significant change with respect to CDDP group.

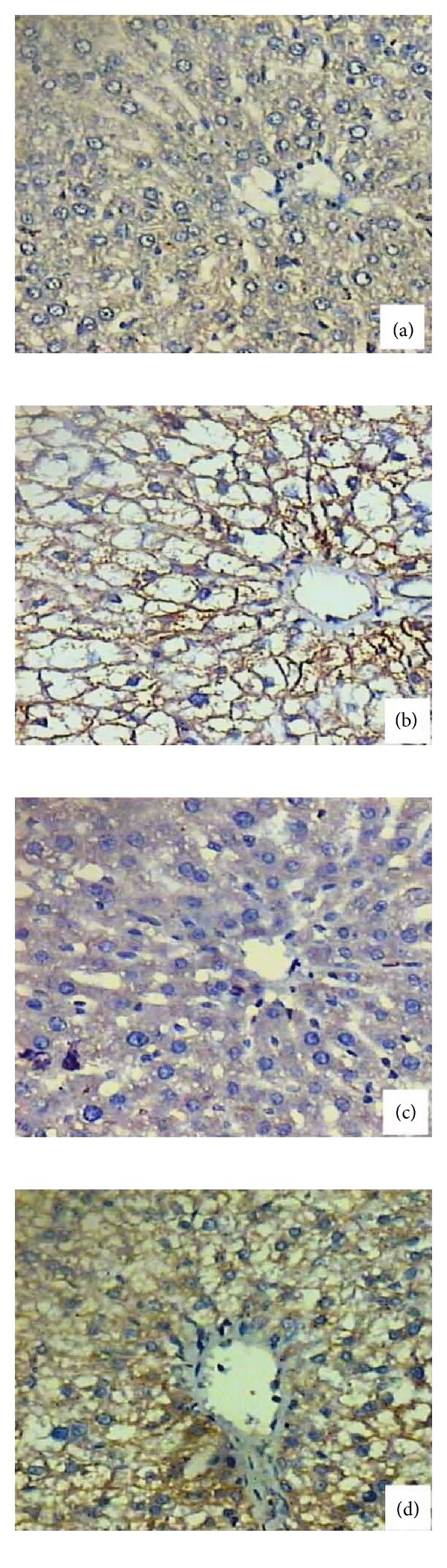

NF-κB is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that has been proposed to be the sensor for oxidative stress [26]. The immunostaining activity for NF-κB was increased in CDDP group compared with control indicating the oxidative stress effect induced by CDDP, while administration of MNLE decreased the number of immunostained cells indicating its antioxidant effect (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

NF-κB expression changes in the liver of rats. (a) Normal liver showing very weak expression for NF-κB. (b) Treated liver with cisplatin showing positive expression for NF-κB. (c) Neem treated liver showing negative expression for NF-κB. (d) Treated liver with cisplatin and MNLE showing medium expression for NF-κB (400x).

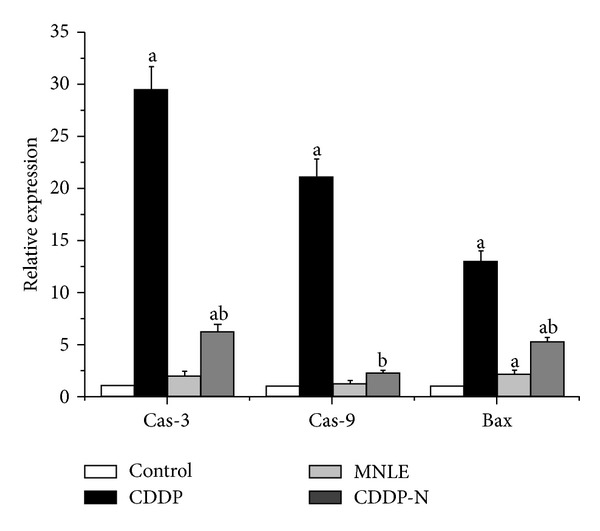

In this study, apoptosis in the liver was investigated with PI; comparison of apoptotic activities groups are shown in supplementary data, (see Figure 1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/741817); we observed that the number of apoptotic cells were increased in the liver of CDDP group when compared with other groups, but in MNLE and CDDP group, there were highly decreased in apoptotic cell numbers, which was confirmed by the results of real time PCR that have shown that there are increases in the expression of the proapoptotic gene Bax and the caspases-3 and 9 in the liver treated with CDDP, while treatment with MNLE has decreased the expression of these genes (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relative quantification using RT-qPCR of mRNA expression of caspase-3, 9, and Bax genes in liver of rats treated with cisplatin and neem leaves extract. a P < 0.05, significant change with respect to Control; b P < 0.05, significant change with respect to CDDP group.

4. Discussion

Different strategies have been proposed to inhibit CDDP-induced toxicity [27]. Development of therapies to prevent the action of generation of free radicals may influence the progression of oxidative liver damage induced by CDDP. Recent studies suggest that using plant derived chemopreventive agents in combination with chemotherapy can enhance the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents and lower their toxicity to normal tissues [28, 29].

Neem is one of those candidate plants which has chemoprotective effect and strong antioxidant potential [30, 31]. The components of the neem tree, like bark, seed, leaf, fruit, gum, oil, and so forth, contain compounds offering some impressive therapeutic applications [12]. There are several reported active compounds in neem plant, like nimbin, azadirachtin, nimbidiol, quercetin, and nimbidin [32, 33]. In a study by Mallick et al. [34] they confirmed nontoxic effect of neem leaves extract on rat liver and kidney, even in higher doses exceeding the effective dose.

The present study has evaluated the effect of MNLE on rats with CDDP-induced hepatotoxicity. Earlier experimental studies have shown that a minimum dose of CDDP (5 mg/kg bwt, i.p) was sufficient to induce hepato and nephrotoxicity in rats [35–37].

The liver is known to accumulate significant amounts of CDDP, second only to the kidney [38]; thus hepatotoxicity can be associated with CDDP treatment [35]. Our study showed many histopathological and biochemical abnormalities in the liver of CDDP-injected animals with single dose (5 mg/kg bwt), which is inconsistent with the previous results [38, 39]. Moreover, the treatment with MNLE (500 mg/kg) for 5 days ameliorated CDDP-induced liver damages associated with free radical production [5, 6] by enhancing the enzyme activity to normal values and preserving the liver parenchyma; that is, the appearance of the hepatocytes, sinusoids, Von Kupffer cells, and the portal triad was similar to the control rats; these results are inconsistent with the previous studies [40, 41].

El-Sayyad et al. [38] reported that light microscopic observations revealed that CDDP caused hepatotoxicity, including dissolution of hepatic cords, focal inflammation and necrotic tissues, periportal fibrosis, degeneration of hepatic cords, and increased apoptosis. It is well known that CDDP induces oxidative stress [42]. Indeed, some recent studies have suggested that oxidative stress plays an important mechanism in CDDP-induced hepatotoxicity [5, 43–46].

Reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions, and hydroxyl radicals are generated under normal cellular conditions and are immediately detoxified by major scavenger enzymatic and nonenzymatic molecules [47]. However, excessive ROS production by CDDP causes antioxidant imbalance and leads to lipid peroxidation and antioxidant depletion [48].

In our study, the major scavenger enzymes activities (SOD, CAT, GPx, GST, and GR) were significantly decreased in liver of CDDP -treated rats our results are in agreement with results obtained earlier [39, 49, 50]. This finding can be explained by CDDP-induced increase in free radical generation or a decrease in amounts of protecting enzymes against lipid peroxidation [49].

Cisplatin is accumulated in its target organs by covalently binding with their proteins [51]. This can affect their antioxidant enzymes which are the first line of defense against any oxidative insult to the cells. CDDP caused nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity evidenced by marked decline in activity of the antioxidant enzymes [52].

CDDP induces nitrosative stress by NO production as secondary event following increase in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [53]. In the current study NO production in the CDDP-treated group was significantly higher than that in the control group; our results are consistent with the results obtained by Kart et al. [39], who have shown that there is strong immunoreactivity against iNOS in the liver tissue of the CDDP-treated group. Chirino et al. [54] reported that inhibition of iNOS reduced the CDDP-induced renal damage and nitrosative stress.

Exogenous and endogenous protective agents with antioxidant properties were reported to show some protective effects in CDDP-induced hepatotoxicity. Neem is one promising agent against various toxicities associated with oxidative stress and peroxidative damage. Neem was shown to have prominent antioxidant, radical-scavenging, and antiperoxidative activities [55]. In the current study, MNLE (500 mg/kg) for 5 days of treatment ameliorated CDDP toxicity, indicated by significant reduction in the elevated LPO and NO levels and also normalized tissue GSH level.

In the present study, injection of CDDP to female rats resulted in elevating functional markers of liver in the serum. This is a clear indication of hepatotoxicity caused by CDDP as the markers are released by the damaged organs in the circulatory system. A marked recovery was observed in the markers of liver function after combination treatment by CDDP with MNLE. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain the pathological status of liver after CDDP treatment [56, 57].

Identification of agents that inhibit carcinogen activation, phase II detoxification, and abrogation of NF-κB signaling has become a major focus of cancer chemoprevention in recent years [58]. Our results revealed that the immunohistochemical expression of NF-κB has shown a strong immunoreactivity in the CDDP-treated group, while treatment with MNLE has decreased the number of positive cells. Our results are consistent with the results obtained by Manikandan et al. [59], who have shown that neem leaf subfraction has a potential role in inhibiting NF-κB.

A mechanism of CDDP toxicity is that CDDP-induces liver cell apoptosis by cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation [56]. Our results showed that treatment with MNLE has decreased the expression of Bax, caspase-3 and 9.

In conclusion, results of the current study suggest that oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation along with nitrosative stress are important features in CDDP hepatotoxicity. CDDP hepatotoxicity is associated with ROS production and might contribute to oxidative stress. However, treatment with MNLE was found to reduce the CDDP-induced liver chemical changes and apoptotic cell numbers. This may be due to antiapoptotic and antioxidant effects of neem extract [60]. Therefore, we suggest (or propose) that usage of neem leaves extract in combination with CDDP in anticancer therapy may help to reduce the CDDP-induced toxicities.

Supplementary Material

Morphological changes visualized under fluorescence microscope with PI staining in liver sections of rats treated with cisplatin and neem leaves extract (400×).

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding the work through the research group Project no. VPP-002.

References

- 1.Fuertes MA, Castilla J, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Novel concepts in the development of platinum antitumor drugs. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;2(4):539–551. doi: 10.2174/1568011023353958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Türk G, Ateşşahin A, Sönmez M, Çeribaşi AO, Yüce A. Improvement of cisplatin-induced injuries to sperm quality, the oxidant-antioxidant system, and the histologic structure of the rat testis by ellagic acid. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;89(5, supplement):1474–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lippard SJ. New chemistry of an old molecule: cis-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2] Science. 1982;218(4577):1075–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.6890712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(4):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratibha R, Sameer R, Rataboli PV, Bhiwgade DA, Dhume CY. Enzymatic studies of cisplatin induced oxidative stress in hepatic tissue of rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;532(3):290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu Y, Cederbaum AI. Cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity is enhanced by elevated expression of cytochrome P450 2E1. Toxicological Sciences. 2006;89(2):515–523. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirino YI, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Role of oxidative and nitrosative stress in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;61(3):223–242. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadzuka Y, Shimizu Y, Takino Y. Role of glutathione S-transferase isoenzymes in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in the rat. Toxicology Letters. 1994;70(2):211–222. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai Y, Nakao T, Kunimura N, Kohda Y, Gemba M. Relationship of intracellular calcium and oxygen radicals to cisplatin-related renal cell injury. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;100(1):65–72. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0050661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arakaki J, Suzui M, Morioka T, et al. Antioxidative and modifying effects of a tropical plant Azadirachta indica (Neem) on azoxymethane-induced preneoplastic lesions in the rat colon. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2006;7(3):467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Research Council (U.S.) Board on Science and Technology for International Development: Neem: A Tree for Solving global Problems: Report of an Ad Hoc Panel of the Board on Science and Technology for International Development, National Research Council. Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswas K, Chattopadhyay I, Banerjee RK, Bandyopadhyay U. Biological activities and medicinal properties of neem (Azadirachta indica) Current Science. 2002;82(11):1336–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dkhil MA, Al-Quraishy S, Abdel Moneim AE, Delic D. Protective effect of Azadirachta indica extract against Eimeria papillata-induced coccidiosis. Parasitology Research. 2013;112(1):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1957;28(1):56–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szasz G. A kinetic photometric method for serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Clinical Chemistry. 1969;15(2):124–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belfield A, Goldberg DM. Revised assay for serum phenyl phosphatase activity using 4-amino-antipyrine. Enzyme. 1971;12(5):561–573. doi: 10.1159/000459586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King EJ, Coxon RV. Determination of bilirubin with precipitation of the plasma proteins. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1950;3:248–259. doi: 10.1136/jcp.3.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Analytical Biochemistry. 1979;95(2):351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Analytical Biochemistry. 1982;126(1):131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1959;82(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishikimi M, Appaji Rao N, Yagi K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1972;46(2):849–854. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods in Enzymology. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paglia DE, Valentine WN. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1967;70(1):158–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Factor VM, Kiss A, Woitach JT, Wirth PJ, Thorgeirsson SS. Disruption of redox homeostasis in the transforming growth factor-α/c-myc transgenic mouse model of accelerated hepatocarcinogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(25):15846–15853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Rio D, Stewart AJ, Pellegrini N. A review of recent studies on malondialdehyde as toxic molecule and biological marker of oxidative stress. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2005;15(4):316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Angio CT, Finkelstein JN. Oxygen regulation of gene expression: a study in opposites. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2000;71(1-2):371–380. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saleh S, El-Demerdash E. Protective effects of L-arginine against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and toxicity: role of nitric oxide. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2005;97(2):91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silici S, Ekmekcioglu O, Kanbur M, Deniz K. The protective effect of royal jelly against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress in rats. World Journal of Urology. 2011;29(1):127–132. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0543-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaki-Doi S, Hashimoto K, Yamamura M, Kamei C. Antihypertensive activities of royal jelly protein hydrolysate and its fractions in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Medica Okayama. 2009;63(1):57–64. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sithisarn P, Supabphol R, Gritsanapan W. Antioxidant activity of Siamese neem tree (VP1209) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;99(1):109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chattopadhyay RR. Possible mechanism of hepatoprotective activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract: part II. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;89(2-3):217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chattopadhyay RR, Sarkar SK, Ganguly S, Banerjee RN, Basu TK, Mukherjee A. Hepatoprotective activity of Azadirachta indica leaves on paracetamol induced hepatic damage in rats. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1992;30(8):738–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhanwra S, Singh J, Khosla P. Effect of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaf aqueous extract on paracetamol-induced liver damage in rats. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2000;44(1):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallick A, Ghosh S, Banerjee S, et al. Neem leaf glycoprotein is nontoxic to physiological functions of Swiss mice and Sprague Dawley rats: histological, biochemical and immunological perspectives. International Immunopharmacology. 2013;15(1):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao Y, Lu X, Lu C, Li G, Jin Y, Tang H. Selection of agents for prevention of cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity. Pharmacological Research. 2008;57(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarladacalisir YT, Kanter M, Uygun M. Protective effects of vitamin C on cisplatin-induced renal damage: a light and electron microscopic study. Renal Failure. 2008;30(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/08860220701742070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ateşşahin A, Karahan I, Türk G, Gür S, Yilmaz S, Çeribaşi AO. Protective role of lycopene on cisplatin-induced changes in sperm characteristics, testicular damage and oxidative stress in rats. Reproductive Toxicology. 2006;21(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Sayyad HI, Ismail MF, Shalaby FM, et al. Histopathological effects of cisplatin, doxorubicin and 5-flurouracil (5-FU) on the liver of male albino rats. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2009;5(5):466–473. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kart A, Cigremis Y, Karaman M, Ozen H. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) ameliorates cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity in rabbit. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2010;62(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kupradinun P, Tepsuwan A, Tantasi N, Meesiripun N, Rungsipipat A, Kusamran WR. Anticlastogenic and anticarcinogenic potential of Thai bitter: gourd fruits. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2011;12(5):1299–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorababu M, Joshi MC, Bhawani G, Kumar MM, Chaturvedi A, Goel RK. Effect of aqueous extract of neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves on offensive and diffensive gastric mucosal factors in rats. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2006;50(3):241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srivastava RC, Farookh A, Ahmad N, Misra M, Hasan SK, Husain MM. Evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide in cisplatin-induced toxicity in rats. BioMetals. 1996;9(2):139–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00144618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y, Cederbaum AI. Cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity is enhanced by elevated expression of cytochrome P450 2E1. Toxicological Sciences. 2006;89(2):515–523. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iraz M, Ozerol E, Gulec M, et al. Protective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) administration on cisplatin-induced oxidative damage to liver in rat. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2006;24(4):357–361. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mansour HH, Hafez F, Fahmy NM. Silymarin modulates cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity in rats. Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2006;39(6):656–661. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santos NAG, Bezerra CSC, Martins NM, Curti C, Bianchi MLP, Santos AC. Hydroxyl radical scavenger ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by preventing oxidative stress, redox state unbalance, impairment of energetic metabolism and apoptosis in rat kidney mitochondria. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2008;61(1):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0459-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2010;4(8):118–126. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weijl NI, Elsendoorn TJ, Lentjes EGWM, et al. Supplementation with antioxidant micronutrients and chemotherapy-induced toxicity in cancer patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. European Journal of Cancer. 2004;40(11):1713–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karadeniz A, Simsek N, Karakus E, et al. Royal jelly modulates oxidative stress and apoptosis in liver and kidneys of rats treated with cisplatin. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/981793.981793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhattacharyya S, Mehta P. The hepatoprotective potential of Spirulina and vitamin C supplemention in cisplatin toxicity. Food and Function. 2012;3(2):164–169. doi: 10.1039/c1fo10172b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hightower RD, Sevin B-U, Perras JP, et al. Comparison of U-73,975 and cisplatin cytotoxicity in fresh cervical and ovarian carcinoma specimens with the ATP-chemosensitivity assay. Gynecologic Oncology. 1992;47(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90104-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hassan I, Chibber S, Naseem I. Ameliorative effect of riboflavin on the cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity under photoillumination. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2010;48(8-9):2052–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curran RD, Ferrari FK, Kispert PH, et al. Nitric oxide and nitric oxide-generating compounds inhibit hepatocyte protein synthesis. The FASEB Journal. 1991;5(7):2085–2092. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.1707021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chirino YI, Trujillo J, Sánchez-González DJ, et al. Selective iNOS inhibition reduces renal damage induced by cisplatin. Toxicology Letters. 2008;176(1):48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gangar SC, Koul A. Azadirachta indica modulates carcinogen biotransformation and reduced glutathione at peri-initiation phase of benzo(a)pyrene induced murine forestomach tumorigenesis. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(9):1229–1238. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martins NM, Santos NAG, Curti C, Bianchi MLP, Dos Santos AC. Cisplatin induces mitochondrial oxidative stress with resultant energetic metabolism impairment, membrane rigidification and apoptosis in rat liver. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2008;28(3):337–344. doi: 10.1002/jat.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ezz-Din D, Gabry MS, Farrag ARH, Abdel Moneim AE. Physiological and histological impact of Azadirachta indica (neem) leaves extract in a rat model of cisplatin-induced hepato and nephrotoxicity. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research. 2011;5(23):5499–5506. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jana S, Mandlekar S. Role of phase II drug metabolizing enzymes in cancer chemoprevention. Current Drug Metabolism. 2009;10(6):595–616. doi: 10.2174/138920009789375379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manikandan P, Ramalingam SM, Vinothini G, et al. Investigation of the chemopreventive potential of neem leaf subfractions in the hamster buccal pouch model and phytochemical characterization. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;56:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bedri S, Khalil EA, Khalid SA, et al. Azadirachta indica ethanolic extract protects neurons from apoptosis and mitigates brain swelling in experimental cerebral malaria. Malaria Journal. 2013;12(1, article 298) doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Morphological changes visualized under fluorescence microscope with PI staining in liver sections of rats treated with cisplatin and neem leaves extract (400×).