Abstract

Naturally occurring anziaic acid was very recently reported as a topoisomerase I inhibitor with antibacterial activity. Herein total synthesis of anziaic acid and structural analogues is described and the preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) has been developed based on topoisomerase inhibition and whole cell antibacterial activity.

Introduction

DNA topoisomerases are involved in the processes of DNA replication and transcription by controlling the topology of DNA.1, 2 Topoisomerases can be divided into types I and II subclasses according to the number of strands cut in the mechanism.3 As topoisomerases are essential for normal cellular processes and cell proliferation, topoisomerase inhibitors can lead to cell death by binding and stabilizing cleavable topoisomerase-DNA complexes and preventing subsequent religation of the cleaved DNA strand. In this regard, topoisomerases represent attractive targets in antibacterial and anticancer drug discovery.4–7 Clinically, semisynthetic camptothecin derivatives topotecan and irinotecan inhibit human type IB topoisomerases and have been used for the treatment of various cancers.8, 9 In addition, the human type IIA topoisomerases are targets for anticancer drug classes of podophyllotoxins8 (etoposide and teniposide) and anthracyclines.10 Fluoroquinolones, one of the most successful antibiotic classes, exert their antibacterial activity by inhibiting type IIA topoisomerases (DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV).11

The continuing emergence and prevalence of multidrug resistant bacterial pathogens, such as methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus,12 extensively drug resistant tuberculosis,13 fluoroquinolone resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa,14 and carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae15 have become an alarming and serious public health threat. Therefore, the new chemotype antibacterial agents with novel targets and mode of action are highly needed to combat pathogenic and drug resistant microorganisms. Bacterial topoisomerase I belonging to the type IA topoisomerase subfamily has emerged as a promising target for developing new antibiotics and notably, currently no clinically used antibiotics target type IA topoisomerase enzyme.4, 6, 16 In this context, new, potent, and selective type IA topoisomerase inhibitors may be developed as effective antibacterial agents with therapeutic potential for bacterial pathogens resistant to current antibiotics.

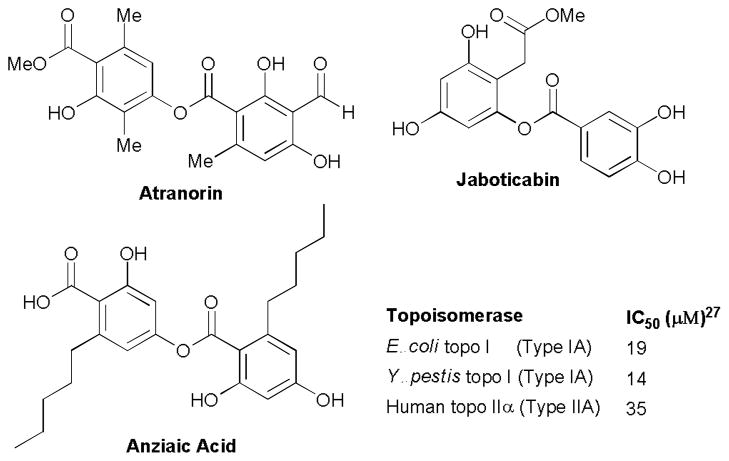

Natural product has been one of the most important and successful sources of novel antibacterial agents.17–20 Naturally occurring depsides which commonly exist in lichens showed promising and diverse biological activities. As examples, atranorin (Fig. 1) from lichen Parmelia reticulata was reported to exhibit antifungal activity against S. rolfsii (ED50 = 39.70 μg/mL).21 Jaboticabin from the fruit of jaboticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) showed antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities with therapeutic potential for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as anticancer activity.22, 23 Anziaic acid,24–26 a depside isolated from lichen Hypotrachyna sp., was very recently found to exhibit inhibitory activity against bacterial (Y. pestis and E. coli) topoisomerase I and human topoisomerase II with IC50 values of 14–19 and 35 μM, respectively.27 This natural product also demonstrated whole cell antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis and a membrane permeable strain (BAS3023) of Escherichia coli with minimum inhibitory activity (MIC) values of 6 and 12 μg/mL, respectively.27

Fig. 1.

Structures of selected naturally occurring bioactive depsides.

In our continued effort to discover novel chemotype antibacterial agents, we have employed emerging natural product leads as medicinal chemistry starting points, guided by whole cell activity-driven approach and followed by target deconvolution and identification.28, 29 Recently, we initiated this topoisomerase I target-driven antibacterial research program. In particular, the promising bacterial topoisomerase I inhibition and whole cell antibacterial activity and the symmetrical and dimeric structural features of anziaic acid attracted our interest toward its resynthesis and biological evaluation of its structural analogues. Here the synthesis of anziaic acid and analogues is described and the preliminary SAR is reported.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

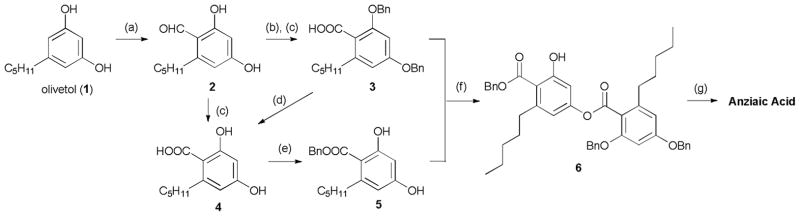

Structurally, anziaic acid is a dimer of 2,4-dihydroxy-6-n-pentylbenzoic acid (4), and was previously synthesized by Asahina and Hiraiwa30 and Elix.31 In this work, a convergent synthesis of anziaic acid was achieved from commercially available starting material (Scheme 1). First, 2 was obtained from olivetol (1) via Vilsmeier-Haack reaction in moderate yield. The two phenol hydroxyl groups were protected with benzyl groups using potassium carbonate as the base, followed by oxidization with NaClO2 to yield the phenol-protected acid product 3 in 61% yield. The acid-protected phenol (5) was synthesized following two sequential steps of oxidation of 2 and selective benzyl ester protection of carboxylic acid in 4.31 Compound 4 was also prepared by debenzylation of 3 with higher yield and purity. Once the two key intermediates are in hand, subsequent selective condensation of 3 and 5 was performed32 to afford benzyl protected dimeric precursor 6 in 64% yield by using trifluoroacetic acid anhydride as a condensation reagent. Finally, the benzyl groups were removed under palladium on carbon (Pd/C) and hydrogen atmosphere to give the synthetic anziaic acid in 95% yield.

Scheme 1.

Total synthesis of anziaic acid: Reagents and conditions: (a) DMF, POCl3, 0 °C to rt, 56%; (b) BnBr, K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 70%; (c) NaClO2, NaH2PO4, DMSO/H2O, 61% (3) and 50% (4); (d) Pd/C, H2, ethyl acetate, 97%; (e) BnBr, KHCO3, DMF, 92%; (f) (CF3CO)2O, toluene, 64%; (g) Pd/C, H2, ethyl acetate, 95%.

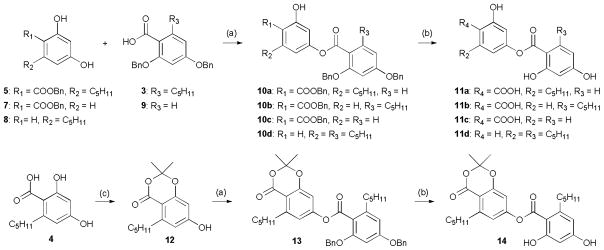

Next, to investigate the effect of different substituents of the anziaic acid scaffold, such as the metal chelating salicylic acid motif and two lipophilic n-pentyl alkyl groups, a series of anziaic acid analogues (Scheme 2) were designed and synthesized following the same synthetic strategy as that used in the synthesis of anziaic acid. Briefly, the ester condensation of the acid-protected phenol monomer 5, 7, 8, or 12 and the phenol-protected acid monomer 3 or 9 yielded the benzyl protected dimers 10a-d or 13, which could be transformed into the corresponding acid-phenol products 11a-d or 14 following final debenzylation reaction.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of anziaic acid analogues 11a-d and 14: Reagents and conditions: (a) 3 (for 13), (CF3CO)2O, toluene, 57–85%; (b) Pd/C, H2, ethyl acetate, 80–100%; (c) SOCl2/acetone/DMAP, 1,2-dimethoxyethane, 0 °C to rt, 39%.

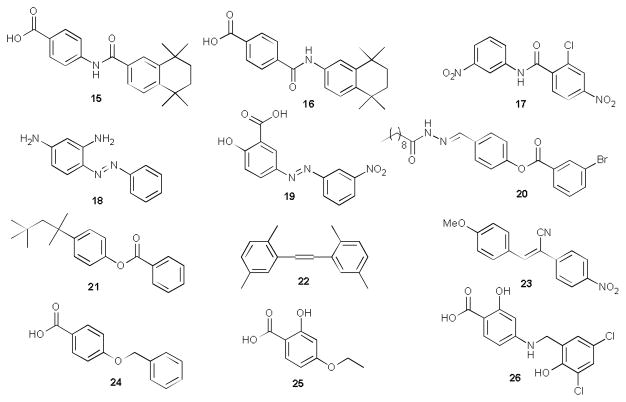

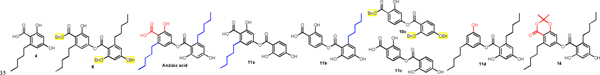

In addition, to further expand the chemical diversity of existing anziaic acid derivatives and to investigate if this dimeric scaffold possesses any tractable topoisomerase inhibition and antibacterial activity, a focused compound collection with structural similarity to anziaic acid and with diverse linkers (e.g., amide or reverse amide in 15–17, the azo N=N linkage in 18 and 19, ester linker in 20 and 21, C=C bond in 22 and 23, -OCH2- linkage in 24 and 25 and -NHCH2- in 26) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (purity ≥97%, Fig. 2) and included in our screening. Structurally, these compounds possess a wide array of chemical functionalities and linkers, thus the screening data of these selected compounds may provide additional insights toward probing the specificity of structural features (e.g., the metal chelating motif, the dimeric scaffold, and the ester linker) of anziaic acid and establishing the preliminary SAR for enzyme and whole cell activity.

Fig. 2.

Structural analogues 15-26 of anziaic acid included in the screen.

Biological studies

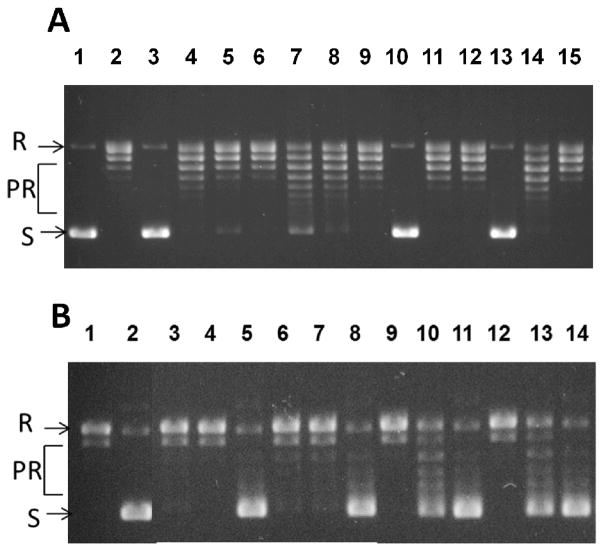

Thus synthesized anziaic acid and its analogues were evaluated for their ability to inhibit topoisomerase enzyme (representative results shown in Fig. 3) and the growth of whole cell bacteria. The results are summarized in Table 1. In the E. coli topoisomerase I inhibition assay, our synthetic sample of anziaic acid exhibited reproducible topoisomerase I inhibition and antibacterial activity (IC50 = 17.7 μM; MIC = 12.5 μM) as the reported natural product sample isolated from lichen Hypotrachyna sp.27 In contrast, the monomer of anziaic acid, 2,4-dihydroxy-6-pentylbenzoic acid (4), had no inhibitory activity against topoisomerase I and gyrase as well as whole cell bacteria. This data demonstrates that the dimeric scaffold bearing both phenyl rings is required for topoisomerase inhibition and antibacterial activity, ruling out the hydrolysis product 4 of anziaic acid being responsible for the activity.

Fig. 3.

Representative results of topoisomerase inhibition assays. (A) E. coli topoisomerase I inhibition assays with supercoiled plasmid DNA. (S) substrate. Lane 1: no enzyme; Lane 2: DMSO control; Lanes 3–6: 31.2, 23.6, 17.7, 13.2 μM (anziaic acid); Lanes 7–9: 1000, 500, 250 μM (11d); Lanes 10–12: 1000, 500, 250μM (11b); Lanes 13–15: 1000, 500, 250 μM (11a). R: relaxed DNA; PR: Partially relaxed DNA. (B) E. coli gyrase inhibition assays with relaxed plasmid DNA. Lane 1: no enzyme; Lane 2: DMSO control; Lanes 3–5: 62.5, 31.2, 23.6 μM (anziaic acid); Lanes 6–8: 1000, 500, 250 μM (11d); Lanes 9–11: 500, 250, 125μM (11b); Lanes 12–14: 500, 250, 125 μM (11a).

Table 1.

Evaluation of anziaic acid and analogues against topoisomerases and whole cell bacteriaa

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | MW (g/mol) | cLogPb |

E. coli Topo I inhibition IC50 (μM) |

Human Topo IIα inhibition IC50 (μM) |

E. coli DNA gyrase IC50 (μM) |

B. subtilis MIC (μM) |

E. coli MIC (μM) |

| 4 | 224.25 | 3.34 | 1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >200 | >200 |

| 6 | 700.86 | - | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >200 | >200 |

| Anziaic acid (isolated natural product)27 | 430.49 | 7.77 | 19 | 35 | 19 | 14 | 28 |

| Anziaic acid (synthetic sample) | 430.49 | 7.77 | 17.7 | 35 | 23.6 | 12.5 | 100 |

| 10c | 560.59 | 9.25 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >200 | >200 |

| 11a | 360.36 | 5.15 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 50 | 200 |

| 11b | 360.36 | 6.05 | 250 | 125 | 250 | 50 | >200 |

| 11c | 290.23 | 3.44 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >200 | >200 |

| 11d | 386.48 | 7.92 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 3.12 | 25 |

| 14 | 470.55 | 9.42 | >1000 | 500 | >1000 | 50 | >200 |

| 15 | 351.44 | 6.34 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | 50–100 | 200 |

| 16 | 351.44 | 6.38 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | 100 | 400 |

| 17 | 321.67 | 2.75 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >800 | >800 |

| 18 | 212.25 | 2.35 | 125–250 | n.d. | n.d. | 400 | 200–400 |

| 19 | 287.23 | 4.27 | 62.5–125 | n.d. | n.d. | 200 | 200 |

| 20 | 473.40 | 8.04 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >800 | >800 |

| 21 | 310.43 | 7.30 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >800 | >800 |

| 22 | 236.35 | 6.83 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >800 | >800 |

| 23 | 280.28 | 3.12 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >800 | >800 |

| 24 | 228.24 | 3.79 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >400 | >400 |

| 25 | 182.17 | 2.76 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | >400 | >400 |

| 26 | 328.15 | 4.02 | >250 | n.d. | n.d. | 200 | 200 |

n.d.-not determined.

The n-octanol/water partition coefficient (LogP) of compounds was calculated using ChemBioOffice® Ultra version 12.0 from CambridgeSoft Corporation.

In addition, compared with the prototype anziaic acid, benzyl fully protected compound 6 and acetal protected variant 14 were inactive against E. coli topoisomerase I and DNA gyrase; compound 11d with the absence of the carboxylic acid group showed very weak activity (IC50 = 250–500 μM). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the absent or masked carboxylic acid group of anziaic acid had a detrimental effect on topoisomerase I and gyrase inhibition. This suggests that interaction of the acidic carboxylate with divalent metal ions at the active site might be required for inhibition of these types IA and IIA topoisomerase activities that require divalent ions for their catalytic activity.27

In terms of the effects of the n-pentyl lipophilic substituents of anziaic acid, removal of either one n-pentyl alkyl group in anziaic acid (compounds 11a and 11b) significantly reduced the inhibitory activities against topoisomerase I and DNA gyrase (IC50 = 250–500 μM), which is about 11–28 fold decrease relative to anziaic acid (IC50 = 17.7–23.6 μM). Compound 11c, with both n-pentyl groups removed, led to the complete loss of both enzyme inhibition and antibacterial activities. This data illustrates that the lipophilic alkyl groups significantly enhance both enzyme inhibitory and whole cell antibacterial activity and may play an important role in hydrophobic interactions with topoisomerase enzyme binding.

Interestingly, in vitro antibacterial evaluation revealed that 11d with the carboxylic acid group absent (MIC = 3.12 and 25 μM against B. subtilis and a membrane permeable strain of E. coli, respectively) and the acetal protected anziaic acid 14 (MIC = 50 μM against B. subtilis) exhibited moderate to good antibacterial activity, despite very weak or no activity (IC50 = 500 and >1000 μM for 11d and 14, respectively) in the topoisomerase I enzyme assay. These data indicate that these two compounds may inhibit bacterial growth by a mechanism independent of topoisomerase inhibition, which does not require the presence of the carboxylic acid group.

Most of the analogues 15-26 with diverse linkers were not active in the test assays except that compounds 18 and 19 with the azo linker exhibited weak to moderate topoisomerase inhibition (IC50 = 62.5–250 μM) and antibacterial activity(MIC = 200–400 μM).

Finally, these active compounds were also found to inhibit human topoisomerase IIα enzyme in the same pattern as DNA gyrase and topoisomerase I. Further work is warranted to systematically optimize and evaluate advanced anziaic acid analogues in an effort to discover more selective bacterial topoisomerase I inhibitors with improved potency and specificity profiles and antibacterial therapeutic potential.

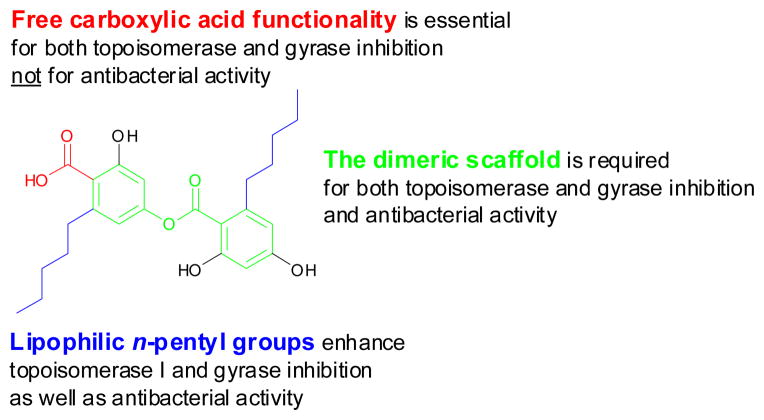

On the basis of these data, a preliminary SAR has been obtained and is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Preliminary SAR.

Conclusions

In summary, anziaic acid and its analogues were synthesized and evaluated against topoisomerases, DNA gyrase, and Bacillus subtilis as well as a membrane permeable strain of E. coli. Preliminary SAR studies demonstrate that the dimeric scaffold and the free carboxylate group of anziaic acid are essential in both topoisomerase and gyrase inhibition. However, the carboxylic acid functionality is not required for whole cell antibacterial activity. Furthermore, the lipophilic n-pentyl alkyl groups significantly enhance both topoisomerase enzyme inhibition and antibacterial activity.

Experimental section

Chemistry

General

All reagents and solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL) and were used without further purification. Reactions were monitored either by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or by reverse-phase HPLC with a Shimadzu LC-20A series HPLC system. TLC was performed using glass plates pre-coated with silica gel (0.25 mm, 60-Å pore size, 230–400 mesh, Sorbent Technologies, GA) impregnated with a fluorescent indicator (254 nm). TLC plates were visualized by exposure to ultraviolet light (UV). Debenzylation reactions were done using domnick hunter NITROX UHP-60H hydrogen generator, USA. Flash column chromatography was performed using a Biotage Isolera One system and a Biotage SNAP cartridge. Proton and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C NMR) spectra were recorded employing a Bruker AM-400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm), J values were in Hertz. Mass spectra were recorded on a Varian 500-MS IT mass spectrometer using ESI. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded with a BioTOF II ESI mass spectrometer. The purity of compounds was determined by analytical HPLC using a Gemini, 3μm, C18, 110Å column (50 mm × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex) and a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Gradient conditions: solvent A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water) and solvent B (acetonitrile): 0–2.00 min 100% A, 2.00–7.00 min 0–100% B (linear gradient), 7.00–8.00 min 100% B, 8.00–9.00 min 0–100% A (linear gradient), 9.00–10.00 min 100% A, UV detection at 254 and 220 nm.

Representative procedure for the synthesis of dimeric precursors

To a stirred solution of benzyl 2,4-dihydroxy-6-pentylbenzoate (5) (94.3 mg, 0.3 mmol) and 2,4-bis(benzyloxy)-6-pentylbenzoic acid (3) (121.4 mg, 0.3 mmol) in dry toluene (3 mL) was slowly added trifluoroacetic acid anhydride (486 μL, 3.45 mmol) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred overnight. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexane: ethyl acetate = 97: 3) to give 6 as a solid (135 mg, 64%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 11.45 (s, 1H), 7.44–7.23 (m, 15H), 6.63 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (s, 2H), 5.06 (s, 2H), 5.05 (s, 2H), 2.70–2.66 (m, 4H), 1.66–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.35–1.31 (m, 6H), 1.14–1.10 (m, 2H), 1.02–1.01 (m, 2H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.79 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.5 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 171.09, 166.06, 164.41, 161.02, 157.66, 155.27, 148.32, 143.94, 136.49, 136.35, 134.79, 129.10, 128.83, 128.78, 128.71, 128.57, 128.22, 128.11, 127.59, 127.54, 116.13, 115.62, 109.56, 108.78, 107.46, 98.24, 70.70, 70.20, 67.81, 36.84, 33.95, 31.92, 31.86, 31.71, 31.06, 22.60, 22.57, 14.08, 14.04; MS (ESI−): m/z 699.6 [M-H] −; HRMS (ESI+) Calcd for C45H48O7 (M+): 701.3473, Found: 701.3472; HPLC purity: 100% (254 nm), tR: 8.91 min; 100% (220 nm), tR: 8.91 min.

Representative procedure for debenzylation of dimers and synthesis of anziaic acid

A solution of benzyl 4-((2,4-bis(benzyloxy)-6-pentylbenzoyl)oxy)-2-hydroxy-6-pentylbenzoate (6) (135 mg, 0.19 mmol) in ethyl acetate (5 mL) was treated with 10% Pd/C (38 mg). The mixture was stirred at room temperature under 1 bar of H2 atmosphere for ca. 2 h. The reaction was stopped once it was complete (monitored by HPLC). The mixture was filtered through Celite and washed with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layer was evaporated under reduced pressure (the water bath temperature was kept below 30 °C) to give anziaic acid as a white solid (78.6 mg, 95%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, ppm) δ 6.62 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.62–1.60 (m, 4H), 1.34–1.32 (m, 8H), 0.91–0.86 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (100.5 MHz, CD3OD, ppm) δ 173.89, 170.41, 166.05, 164.34, 164.14, 154.90, 149.36, 149.04, 116.22, 113.16, 112.23, 109.03, 105.22, 102.01, 37.73, 36.79, 33.21, 33.13, 32.99, 32.62, 23.60, 23.46, 14.44, 14.38; MS (ESI−): m/z 429.3 [M-H] −; HRMS (ESI+) Calcd for C24H30O7 (M+Na+): 453.1884, Found: 453.1887; HPLC purity: 100% (254 nm), tR: 7.54 min; 100% (220 nm), tR: 7.54 min.

The spectroscopic data of synthetic anziaic acid are consistent with those of isolated anziaic acid natural product from lichen Hypotrachyna sp.27

Synthesis of other structural analogues of anziaic acid is described in the supporting information.

Topoisomerase inhibition assays

The topoisomerase assays were performed as previously described.27 The IC50 values were determined from average of experiments repeated at least twice. Briefly, inhibition of relaxation activity of 10 ng of E. coli topoisomerase I was assayed with 250 ng of supercoiled pBAD/Thio plasmid DNA substrate purified by CsCl gradient. The relaxation reaction was carried out in 20 μL of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/mL gelatin with 0.5 mM MgCl2. After 30 min at 37°C, the reactions were terminated and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Human topoisomerase IIα (from TopoGen) relaxation assay and E. coli DNA gyrase (from New England BioLab) supercoiling assay were carried out as recommended by the suppliers. Relaxed plasmid DNA substrate for DNA gyrase was purchased from New England BioLabs.

Antibacterial testing

The MICs of compounds against different bacterial strains grown in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth were measured with standard microdilution procedures.27 Complete growth inhibition was recorded after 24 h in a 37°C incubator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grants P20RR016467, P20GM103466, and R15AI092315 (D.S.) as well as R01AI069313 (Y.T.). We also thank Drs. Benjamin Clark and Robert Borris for the assistance with collecting the HRMS data of the synthesized compounds.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental synthetic procedures and copies of 1H, 13C NMR spectra and HPLC chromatographs of synthetic intermediates, anziaic acid, and its analogues. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Wang JC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos SM, Tretter EM, Schmidt BH, Berger JM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:827–841. doi: 10.1038/nrm3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:738–748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pommier Y. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:82–95. doi: 10.1021/cb300648v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pommier Y, Leo E, Zhang H, Marchand C. Chem Biol. 2010;17:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tse-Dinh YC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:731–737. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse-Dinh YC. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:3–9. doi: 10.2174/187152607780090748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann JT, Lipp HP. Drug Saf. 2006;29:209–230. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pommier Y. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:789–802. doi: 10.1038/nrc1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailly C. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3611–3640. doi: 10.1021/cr200325f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper DC. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:S24–S28. doi: 10.1086/314056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E. Lancet. 2006;368:874–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guidelines for the Programmatic Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis, 2011 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu DI, Okamoto MP, Murthy R, Wong-Beringer A. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:535–541. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300:2911–2913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagara V, Siker D, Pain J. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1995–2007. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abreu AC, McBain AJ, Simões M. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:1007–1021. doi: 10.1039/c2np20035j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis K. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:371–387. doi: 10.1038/nrd3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clardy J, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:1541–1550. doi: 10.1038/nbt1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3670–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goel M, Dureja P, Rani A, Uniyal PL, Laatsch H. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:2299–2307. doi: 10.1021/jf1049613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynertson KA, Wallace AM, Adachi S, Gil RR, Yang H, Basile MJ, D’Armiento J, Weinstein IB, Kennelly EJ. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1228–1230. doi: 10.1021/np0600999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu SB, Wu J, Yin Z, Zhang J, Long C, Kennelly EJ, Zheng S. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:4035–4043. doi: 10.1021/jf400487g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asahina Y, Hiraiwa M. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1935;68:1705–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elix JA, Wardlaw JH. Aust J Chem. 1997;50:1145–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox CH, Huneck S. Phytochemistry. 1970;9:2057. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng B, Cao S, Vasquez V, Annamalai T, Tamayo-Castillo G, Clardy J, Tse-Dinh YC. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun D, Hurdle JG, Lee R, Lee R, Cushman M, Pezzuto JM. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:1541–1545. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen L, Maddox MM, Adhikari S, Bruhn DF, Kumar M, Lee RE, Hurdle JG, Lee RE, Sun D. J Antibiot. 2013;66:319–325. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asahina Y, Hiraiwa M. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1937;70:1826–1828. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elix JA. Aust J Chem. 1974;27:1767–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P, Zhang Z, Yu B. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8884–8889. doi: 10.1021/jo051384k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.