Abstract

Alloreactive T-cell responses directed against minor histocompatibility (H) antigens, which arise from diverse genetic disparities between donor and recipient outside the MHC, are an important cause of rejection of MHC-matched grafts. Because clinically significant responses appear to be directed at only a few antigens, the selective deletion of naïve T cells recognizing donor-specific, immunodominant minor H antigens in recipients before transplantation may be a useful tolerogenic strategy. We have previously demonstrated that peptide-MHC class I tetramers coupled to a toxin can efficiently eliminate specific TCR-transgenic T cells in vivo. Here, using the minor histocompatibility antigen HY as a model, we investigated whether toxic tetramers could inhibit the subsequent priming of the two H2-Db-restricted, immunodominant T-cell responses by deleting precursor CTL. Immunization of female mice with male bone marrow elicited robust CTL activity against the Uty and Smcy epitopes, with Uty constituting the major response. As hypothesized, toxic tetramer administration prior to immunization increased survival of cognate peptide-pulsed cells in an in vivo CTL assay, and reduced the frequency of corresponding T cells. However, tetramer-mediated decreases in either T-cell population magnified CTL responses against the non-targeted epitope, suggesting that Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ T cells compete for a limited common resource during priming. Toxic tetramers conceivably could be used in combination to dissect or manipulate CD8+ T-cell immunodominance hierarchies, and to prevent the induction of donor-specific, minor H antigen CTL responses in allotransplantation.

Keywords: Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Alloreactivity, MHC, Tetramers, Minor histocompatibility antigens, Immunodominance

1. Introduction

Host immune responses to donor antigens constitute one of the major mechanisms underlying chronic rejection of transplanted organs [1]. Matching MHC antigens reduces anti-donor T-cell responses and improves long-term survival of allografts, such as kidneys [2], but does not provide complete tolerance nor obviate the need for lifelong immunosuppressive therapy [3,4], which in itself can contribute to transplant dysfunction and demise [5]. Diverse non-MHC polymorphisms across the donor genome give rise to minor histocompatibility (H) antigens, which, excepting those encoded by mitochondrial DNA, are presented by classical class I and II molecules to alloreactive T cells [6]. While the frequency of T cells recognizing these epitopes is only a small fraction of those that react to donor MHC molecules, most minor H antigen disparities in outbred populations cannot readily be circumvented by matching, and consequently, these donor-reactive T-cell responses can be clinically significant causes of rejection [7].

A variety of immunomodulatory agents, often in combination, are chronically administered to graft recipients to suppress alloreactive T-cell responses, including anti-metabolites (e.g., mycophenolate), and inhibitors of the calcineurin and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. While effective, it has also become clear that, during the initial induction of transplantation tolerance, deletion of anti-donor T cells is optimally needed to reduce the number of alloreactive effectors to levels that can be controlled by pharmacologic maintenance therapy and peripheral physiologic regulatory mechanisms [8,9]. Accordingly, antibodies against T-cell surface markers have been used as depleting agents for bulk T cells, specific subsets, or those of particular activation status, in both clinical patients (antithymocyte globulin; anti-CD2 and -CD52 mAbs) and experimental models (anti-TCRαβ, -CD3ε, -CD4, -CD8α, -CD25, -CD28, -CD45, -CD154 and -CD223 mAbs) [10]. However, wholesale elimination of polyclonal T cells can result in the loss of Tregs, compromising transplantation tolerance, as well as the deletion of protective T cell responses, increasing the risk of opportunistic infections. Ideally, to induce graft tolerance, only donor-specific T cells would be deleted. At first glance, minor H antigen differences would appear too numerous and diverse to permit such an approach, but fortunately, these antigens are limited by immunodominance mechanisms [6], and hence, are rational targets for intervention. The great majority of minor H antigens in humans [7] and mice [3] are MHC class I-restricted, and their cognate CD8+ T cells can be visualized with fluorescently labeled peptide-MHC (pMHC) class I tetramers [11,12]. Logically, the next step is to determine whether such tetramers can be employed to mediate antigen-specific depletion of these alloreactive T cells. We and others have previously demonstrated that class I tetramers can be used to selectively deliver a lethal hit to CD8+ T cells [13-15]. In two models, injection of “toxic tetramers”( tetramers that were coupled to the ribosome-inactivating phytotoxin, saporin [SAP]) eliminated >75% of adoptively transferred, TCR-transgenic CD8+ T-cell targets, and by removing pathogenic T cells in this same manner, the progression of spontaneous type 1 diabetes mellitus in nonobese diabetic mice could be significantly delayed [13,16].

In this study, we evaluated the capability of toxic tetramers to selectively delete murine alloreactive T cells that recognize minor H antigen, HY [17]. In addition to serving as a useful model, HY is also the most clinically important minor H antigen in solid organ transplantation, associated with the decreased survival of kidney, liver, heart and bone marrow grafts [18-21]. Administration of SAP-conjugated tetramers specific for the two immunodominant epitopes, Uty and Smcy, significantly decreased CTL responses elicited by subsequent immunization. Interestingly, targeting either T-cell specificity had the unintended effect of amplifying CTL responses against the other epitope, suggesting that toxic tetramers could serve as a unique tool to facilitate the discovery of additional subdominant minor H antigen epitopes, an important goal in transplantation tolerance studies [3]. Further, the ability to eliminate specific alloreactive precursors prior to exposure to donor-origin tissue illustrates a new and potentially useful therapeutic strategy for the induction of CTL tolerance to minor H antigens.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Mice

C57BL/6J (B6) mice (Thy1.1 and Thy1.2) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-enhanced transcript for IFN-γ (Yeti) [22] and TCR-transgenic B6.D2TgN(Tcr-Lcmv)327Sdz/Fre (P14) [23] and B6 TgN(Tcr-HY) [24] mice were bred in-house. All mice were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited, specific pathogen-free facility. The mice were typically used at 6 – 8 weeks of age in experiments that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and adhered to published principles of laboratory animal care.

2.2 Cell preparation

Using aseptic technique, cell preparations of bone marrow flushed from tibias and femurs, or spleens disaggregated between glass slides, were depleted of erythrocytes with ammonium chloride lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl4, 1 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA), passed through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and resuspended in PBS containing 0.5% FBS. In some experiments, splenocytes were depleted of CD8α+ T cells or B220+ B cells using the appropriate microbead kit and a QuadroMACS magnetic separator (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). To isolate peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs), venous blood was collected from the superficial temporal vein with a Goldenrod lancet (MEDIpoint Inc., Mineola, NY, USA), diluted into PBS containing 0.15% EDTA, layered over Histopaque-1083 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 minutes; cells at the interface were collected, washed and resuspended in FACS buffer (2% FBS and 0.1% NaN3 in PBS) prior to analysis.

2.3 Immunization for eliciting anti-HY T-cell responses

Female mice were administered a single-cell suspension of fresh, syngeneic male cells (bone marrow or splenocytes) in 200 μL PBS intraperitoneally (IP) or intravenously (IV, via the lateral tail vein).

2.4 Peptide-MHC class I tetramer preparation

The H2-Db-restricted peptides Smcy738-746 (KCSRNRQYL; referred to as Smcy), synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA), and Uty246-254 (WMHHNMDLI; referred to as Uty) and the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein-derived altered peptide ligand gp3333-41C9M (KAVYNFATM; referred to as gp33C9M), produced at the UNC-CH Peptide Synthesis Facility, were each dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 10 mg/mL. To generate pMHC class I complexes, peptides were individually incubated in folding buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 400 mM L-arginine; 5 mM reduced glutathione; 0.5 mM oxidized glutathione; and protease inhibitors) with H2-Db heavy chain purified from E. coli inclusion bodies, and human beta-2 microglobulin, at 10°C for 48-72 hours. Folded complexes were subsequently concentrated with an Amicon stirred ultrafiltration cell (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and purified by gel filtration chromatography. After biotinylation with the BirA enzyme, pMHC class I tetramers were prepared by the fractional addition (1/4 of the total amount every 10 minutes) of streptavidin (SA)-SAP (Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA, USA; 2.5 molecules of SAP per molecule of SA), or phycoerythrin (PE) or allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated SA (Leinco Technologies, St Louis, MO, USA) at a 5:1 or 6:1 (pMHC : streptavidin) molar ratio, as described [13].

2.5 Peptide-MHC class I tetramer administration

Prior to injection, pMHC class I tetramers were sterilized by passage through a 0.22 μm centrifugal filter unit (Ultrafree-MC; EMD Millipore). Mice received 2 IV injections of unmodified or SAP-conjugated Db-tetramers (diluted to 200 μL in PBS) via the lateral tail vein.

2.6 In vivo CTL assay

To prepare target cells, syngeneic female B6 splenocytes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in R-10 medium (10% FBS, 5×10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 IU/mL penicillin in RPMI 1640) containing 10 μg/mL Uty, Smcy, both, or no peptides. After extensive washing, peptide-pulsed cells were labeled with 30 μM Pacific Blue succinimidyl ester (PBSE) and varying concentrations (none, or 0.05, 0.5 or 2.5 μM) of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; both dyes from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 10 min at 22°C, and subsequently quenched with FBS. Labeled, pulsed splenocytes were resuspended in PBS (2 × 107 cells/mL), combined in equal ratios, and adoptively transferred IV (200 μL) into HY-sensitized (14 d post-immunization) and naïve female B6 recipients. To assess CTL activity, differential target cell survival in the spleen was measured by flow cytometry 18-24 h after transfer; any immunized mice that had complete recovery of all targets were considered priming failures and excluded from analysis to prevent overestimating the protective effects of tetramers.

2.7 Staining of cells and flow cytometric analyses

The following fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA; Invitrogen; or BioLegend, San Diego, CA) were used at pre-determined optimal concentrations (clone names are indicated parenthetically): anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), anti-CD19 (eBioID3 or 6D5), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-90.1 (Thy1.1;OX-7), anti-90.2 (Thy1.2; 53-2.1) and anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2). After 10-min incubation with Fc receptor block (anti-mouse CD16/CD32; eBioscience), single-cell suspensions were labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs or pMHC class I tetramers in FACS buffer in 96-well round-bottom polypropylene plates for 45 min at 4°C, washed, and fixed in buffered 1% formaldehyde containing FBS. For detection of intracellular IFN-γ, splenocytes were first incubated in R-10 medium containing fluorochrome-conjugated tetramers in 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene plates for 5 h at 37°C. Brefeldin A (3 μg/mL; eBioscience) was added after the first hour. Cells were permeabilized using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences), performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. List mode data were collected with a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) or CyAn ADP cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and analyzed with Summit software (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Viable cells were discriminated by forward and side scatter characteristics.

2.8 Statistical analyses

Significant differences in means between groups were calculated using a 2-tailed unpaired t test, or 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test, using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

HY is a well-established minor H antigen model system [17,25]. HY antigens are widely expressed proteins encoded by the Y chromosome and consequently, as non-self, are immunogenic in females. Like other H-2b strains, B6 mice are HY “high responders”, and females rapidly and reliably reject syngeneic male tissues, with a typical, accelerated second-set reaction [11]. Since the pioneering work of Billingham and Silvers [26,27], HY incompatibility has provided a frequently used platform for testing strategies to induce tolerance to minor H antigens [28-31], and similarly, was employed in this study to assess the ability of toxic tetramers to inhibit alloreactive CTL responses.

3.1 Kinetics of H2-Db-restricted, HY-reactive CD8+ T-cell populations elicited by immunization with male bone marrow cells

Both direct and indirect priming are necessary to optimally induce anti-HY CTL responses [11,32]. In early experiments, we injected syngeneic male splenocytes (typically 5 - 10 × 106 cells per mouse), but occasionally had female B6 recipients that did not respond (data not shown). To potentially improve immunization efficiency, alternate priming protocols were evaluated. When magnetic separation was used to deplete immunizing splenocytes of either CD8α+ cells, which can act as so-called “veto” cells (donor T cells that delay activation of the host CTL response) [33], or B cells, which have a tolerizing effect on naïve HY-reactive T cells [34], some recipient mice still failed to mount a detectable response (data not shown). Priming with bulk male bone marrow cells has been reported to elicit stronger anti-HY responses than with either splenocytes or dendritic cells, with no differences between IV or IP routes of administration [11]. Similarly, in our hands, IP injection of bone marrow (5 × 106 cells) provided the most robust and consistent anti-HY responses, and this method was used in subsequent experiments.

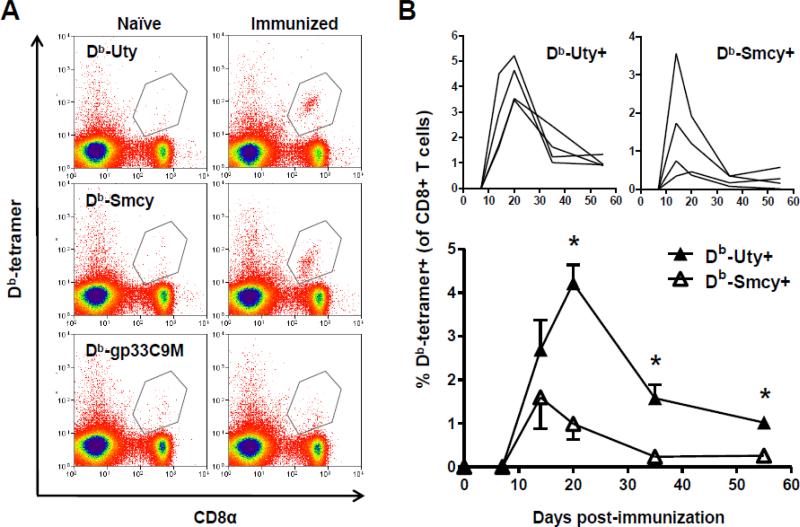

Anti-HY CD8+ T cells recognize two immunodominant epitopes restricted by H2-Db, Uty [35] and Smcy [36]; epitopes derived from Uty and Smcy proteins are also HLA class I-restricted HY targets in humans [3]. After priming of B6 female mice, these T-cell populations can be visualized in peripheral blood by pMHC class I tetramer staining (Fig. 1A). It remains unclear which of these two specificities constitutes the major response; Db-Uty+CTL are usually considered quantitatively and qualitatively superior [11,37,38], but other studies have found the converse, with Db-Smcy+ CTL predominating [33,39]. The graphs at the top of Fig. 1B depict the changes in the frequency of circulating HY-reactive CTL in individual mice after priming, and the bottom graph shows average responses over time. Initially, increases in circulating Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ CTL were similar, with no significant difference in frequency (or cell number – not shown) at 14 d post-immunization. However, the Uty-reactive T-cell population continued to expand for a longer period than did the Smcy-reactive population, and as a consequence, Db-Uty+ CTL ultimately reached a higher peak frequency and remained at significantly greater levels throughout the contraction phase.

Fig. 1.

Upon exposure to male antigen, Db-Uty+ CD8+ T cells exhibit a more vigorous, prolonged expansion than do Db-Smcy+ CD8+ T cells. (A) Flow cytometric dot-plots showing the two immunodominant, HY-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in the peripheral blood of a representative female B6 mouse 14 d after IP administration of syngeneic male bone marrow cells (“immunized”). In all experiments, the Db-restricted, LMCV altered peptide ligand gp33C9M tetramer, and naïve female mice, which do not have detectable HY-reactive CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood [47], served as negative controls. (B) The kinetics of circulating Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ CD8+ T cells after immunization; T-cell expansion and contraction in individual mice are shown in the top graphs (note different y-axis scales). Mean peripheral anti-HY responses (n=4) over time are shown below. The Db-Uty+ CD8+ T-cell percentages were significantly greater at days 20, 35 and 55 (*P<0.05, by two-tailed t-test). Error bars indicate SEM. The data represents one of two independent experiments that yielded the same results.

3.2 Characterization of H2-Db-restricted anti-HY CTL responses

We next sought to compare the effector functions of the two HY-reactive specificities. Splenocytes were collected at 14 d post-immunization, when T cells were sufficiently numerous to permit evaluation, and before either population began contracting. In response to TCR ligation by cognate tetramer, approximately equal proportions of T cells produced nearly identical amounts of IFN-γ, as shown by intracellular staining (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Because ex vivo re-stimulation is necessary to induce cytokine production, this assessment could have failed to disclose differences between the two specificities in their IFN-γ responses to the priming inoculum. To circumvent this potential limitation, we also immunized B6-background, IFN-γ reporter (Yeti) mice that produce YFP upon transcription of the locus [22,40]. The cumulative fraction of each activated, tetramer+ T-cell population that had been induced to produce IFN-γ by male antigen exposure can now be seen to be much greater than that revealed by intracellular staining; once again, however, the two specificities were not significantly different (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Additional analyses of Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ CTL from immunized B6 mice also demonstrated equivalent levels of TNF-α and granzyme B (by intracellular staining; not shown).

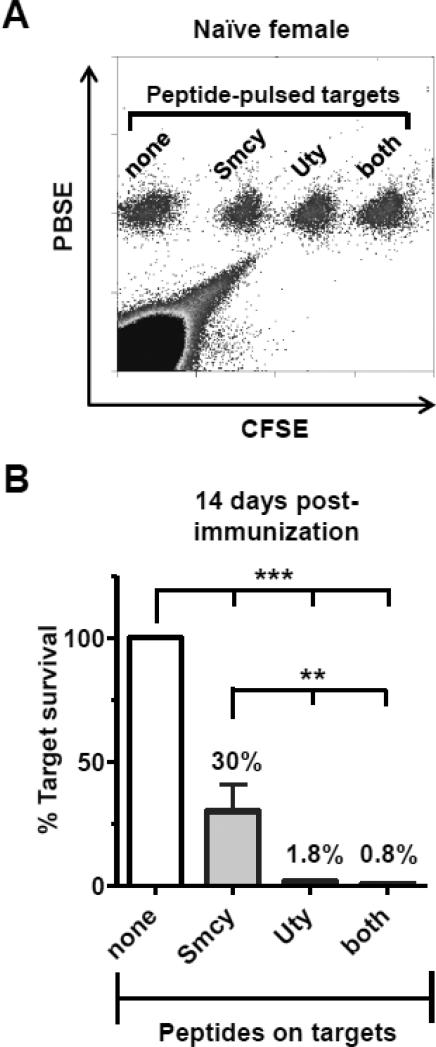

Finally, we directly compared cytotoxic activity at 14 d post-immunization. At this time point, in addition to having detectable circulating tetramer+ T cells, female Thy1.2+ mice had also cleared an immunizing inoculum of Thy1.1+ male splenocytes (Supplemental Fig. 2A). To measure CTL responses, an in vivo assay was used [41]. All peptide-pulsed targets, identified by differential dye staining, were equally recovered in naïve female mice; a representative dot-plot is shown in Fig. 2A. Two weeks after a priming injection of bone marrow cells, targets pulsed with Smcy or Uty (or both) peptides were readily eliminated. Responses against Uty were significantly greater in all experiments (Fig. 2B). On average, 33% of Smcy-pulsed targets survived (vs. unpulsed), while <2% Uty-pulsed cells could be recovered. Because the frequencies of Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ CTL were not different at this time point (Fig. 1B), this observation suggests that anti-Uty CTL are more efficient in vivo on a per-cell basis.

Fig. 2.

CTL activity against Uty-bearing targets is more efficient than responses against targets pulsed with Smcy peptide. (A) Representative dot-plot demonstrating the recovery of unpulsed control (“none”) and peptide-pulsed target cells, discriminated by labeling with different combinations of PBSE and CFSE dyes, from the spleen of a naïve B6 mouse 18 h after IV adoptive transfer. (B) Anti-Uty CTL responses primed by immunization are significantly more efficient than anti-Smcy CTL at removing cognate target cells. Fourteen days after a single injection of male bone marrow, mice were challenged with a mixture of fluorescently labeled, peptide-pulsed, female-origin splenocytes; 24 h later, spleens were harvested and targets were enumerated by flow cytometry. To permit comparison between animals and across experiments, the survival of each peptide-pulsed group was expressed as a percentage of the unpulsed control cells recovered, and all were significantly decreased (***P<0.05), demonstrating CTL activity against these immunodominant epitopes. However, significantly more Uty-pulsed targets were eliminated than those pulsed with Smcy alone (**P<0.05; both analyses by ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test). No CTL responses were observed in naïve control mice (not shown). Error bars in graphs indicate SEM. The graph in (B) represents data combined from four separate experiments.

3.3 Toxin-coupled Db-Uty and Db-Smcy tetramers selectively inhibit anti-HY CTL responses in vivo

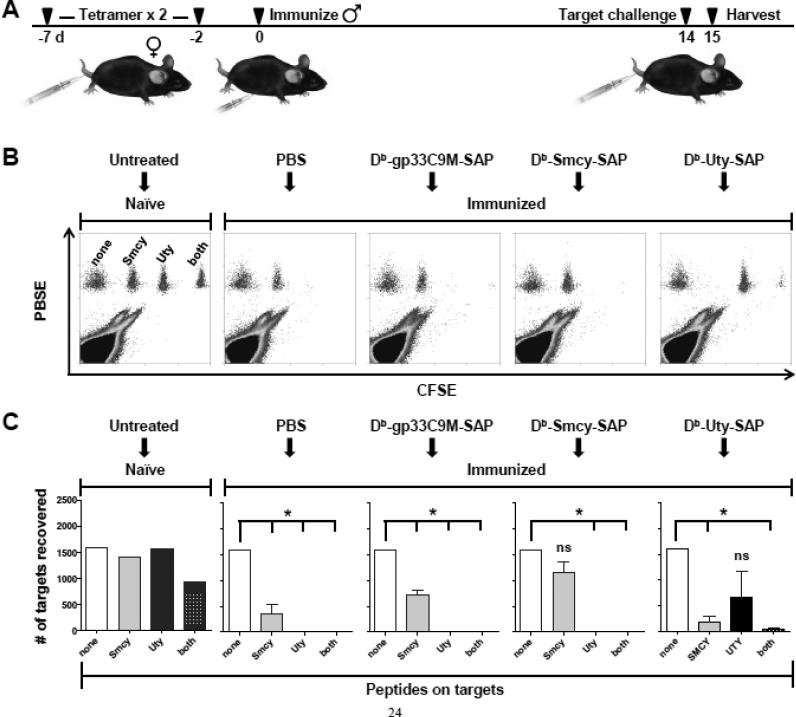

We then investigated whether HY-reactive CD8+ T cells could be removed in vivo by administration of cognate toxic tetramers. In particular, we wished to delete naïve T cells, as such an approach mimics a possible therapeutic intervention that could be initiated prior to allotransplantation. Moreover, naïve T cells appear to be generally more sensitive than effector cells to the toxic effects of SAP-conjugated tetramers (our unpublished data). Additionally, with this strategy, the number of target T cells is quite small: at a typical CD8+ T-cell precursor frequency of 10−5, only ~200 – 500 specific T cells would need to be eliminated in an individual mouse [42]. However, this extremely small number also means that deletional effects could not be directly assessed. Rather, as an indirect measure, we sought to determine whether toxic tetramer administration would remove sufficient precursor T cells to substantially reduce (or ideally, abolish) CTL responses elicited by immunization. This outcome should result in increased survival of the corresponding target cell in the in vivo CTL assay. The design of experiments to test this prediction is shown in Fig. 3A. The dose of toxic tetramer (33 pmol) was based on our previous work [13,16], and in vivo preliminary studies with Db-Uty-SAP (not shown). At this dosage, mice did not exhibit clinical signs of illness. To potentially enhance the efficacy of T-cell deletion, 2 injections of tetramer were given, 5 days apart. While even more closely spaced treatments might appear advantageous, CD8+ T cells can become temporarily refractory to tetramer binding after antigen exposure [43], and consequently, the optimal interdose interval was uncertain. To determine whether this binding resistance effect occurs after tetramer administration, we used Db-gp33+ CD8+ T cells (from an LCMV TCR-transgenic P14 mouse) as a surrogate target. Two days after the injection of cognate Db-gp33C9M tetramer, approximately one-third of P14 T cells are unable to bind tetramer in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 2B). A follow-up experiment demonstrated that Db-gp33C9M tetramer binding rebounded by 5 d post-injection (Supplemental Fig. 2C). It should be noted that fluorophore-labeled tetramers likely overestimate resistance to SAP-conjugated tetramers, as the former are used optimally in the ≥5 nM range, while toxic tetramers are generally effective at subnanomolar doses [13]. Based on these data, toxic tetramer doses were separated by 5 d; this interval also allows the second dose to be administered after any acute adverse hepatic effects of SAP had peaked (at day 2) [13].

Fig. 3.

Administration of SAP-conjugated Db-Uty and Db-Smcy tetramers to HY-naïve female mice decreases cognate CTL responses elicited by immunization. (A) Schematic depicting the timeline of experiments. Female B6 mice (n=3 per group) were injected twice, 5 d apart, with cytotoxic tetramers or PBS. Two days after the second treatment, 5 × 106 syngeneic male bone marrow cells were administered IP to prime anti-HY CTL responses, which were subsequently assayed in vivo 14 d later. Representative dot-plots (B) and mean target recovery (C) demonstrate that treatment with Db-Uty-SAP and Db-Smcy-SAP tetramers prior to male antigen exposure results in increased survival of transferred target cells bearing the corresponding peptides. The PBS and Db-gp33C9M-SAP tetramer-treated groups served as negative and antigen-non-specific controls, respectively. To permit comparison between mice, the number of unpulsed control cells recovered from subjects in each treatment group was normalized to the value obtained from untreated, HY-naïve females. All peptide-pulsed targets were significantly reduced, compared to unpulsed control cells, by CTL activity (*P<0.05, by ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test), except for Smcy-pulsed targets protected by Db-Smcy-SAP, and Uty-pulsed targets protected by Db-Uty-SAP (ns, not significant). The data shown is from one of two independent experiments with the same results. Error bars in graphs indicate SEM.

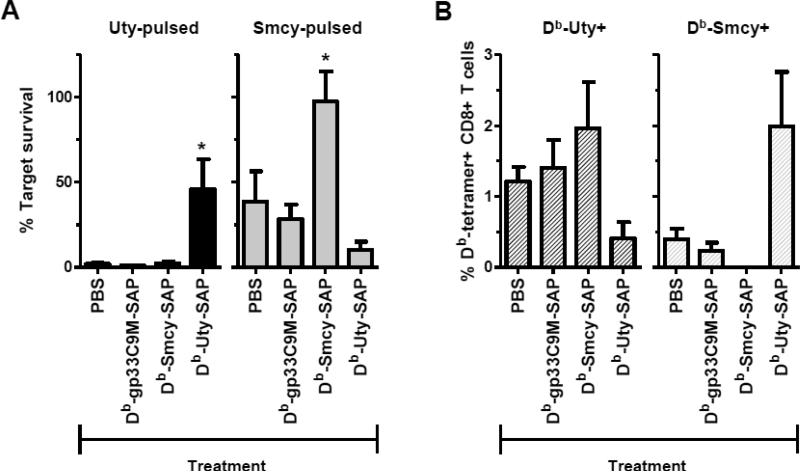

Following the second tetramer injection, CTL precursors were expanded by injection of male bone marrow, and cytotoxic responses compared (Fig. 3B, C). In mice injected with Db-gp33C9M-SAP, the survival of Uty, Smcy, and Uty/Smcy-pulsed targets was significantly decreased, similarly to the PBS-treated control mice, showing that the administration of non-cognate pMHC molecules or SAP did not exert a non-specific effect on the induction of CTL responses. On the other hand, toxic Db-Uty and Db-Smcy tetramers protected their corresponding targets. Within both treatment groups, the recovery of cognate peptide-pulsed cells was not significantly different from that of unpulsed targets, demonstrating a reduction in CTL activity. A repetition of this experiment yielded the same results. When data from the two experiments were analyzed together, significant protective effects were also observed across the treatment groups (Fig. 4A). Administration of Db-Uty-SAP resulted in ~46% Uty-pulsed target survival (vs. unpulsed), compared to 1-2% in other treatment groups. As noted previously (Fig. 2B), Smcy-pulsed targets are cleared less efficiently by CTL; in mice injected with PBS and Db-gp33C9M-SAP, the average recovery of these targets ranged from 28 - 39%. With Db-Smcy-SAP administration, however, survival was increased to 98% of unpulsed control cells.

Fig. 4.

The protection of Uty- and Smcy-pulsed targets by administration of cytotoxic tetramers is associated with a reduction in cognate CD8+ T cells. (A) Treatment of female mice (n=3 mice per group per experiment) with Db-Uty-SAP and Db-Smcy-SAP tetramers before priming significantly decreases specific CTL-mediated elimination of targets (*P<0.05, by ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test). As described for Fig. 3, data were normalized to cell recovery in HY-naïve mice, and expressed as a percentage to permit comparison between experiments. (B) The expansion of Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ CD8+ T cells in the spleens of mice following immunization with male antigen is selectively reduced by prior administration of cytotoxic tetramers. Values in the graph are % tetramer+ T cells, which were determined by subtracting non-specific staining with the PE-labeled Db-gp33C9M tetramer. In B6 mice, true Db-gp33+ T cells occur at a frequency of 1 in ~70,000 CD8+ T cells (0.0014%) [42], so essentially all (>99.9%) tetramer staining of this rare population represents false positive (background) signal. Mean differences between the treatment groups were not significant (by ANOVA). The same results were obtained when specific T-cell numbers, rather than % T cells, were compared (not shown). Graphs (A,B) represent combined data from two independent experiments; error bars indicate SEM.

3.4 Toxic tetramers eliminate cognate T cells

The enhanced recovery of Uty- and Smcy-pulsed targets is presumably the result of toxic tetramer-mediated killing of naïve, HY-reactive T cells. In support of this hypothesis, in a preliminary study, we observed that two injections of unmodified Db-Uty tetramer, which did not eliminate Db-Uty+ T cells, also did not protect Uty-pulsed targets (Supplemental Fig. 2D), suggesting that inhibition of priming did not simply result from prior exposure to pMHC alone. Moreover, our previous reports [13,16] and those of others [15] show that SAP-conjugated tetramers selectively bind to, and subsequently kill, cognate T cells. Using an anti-SAP antibody, binding of the Db-Uty-SAP tetramer to a CD8+ T-cell population in a female mouse sensitized to male antigen can be observed (Supplemental Fig. 2E). Previously, we have demonstrated the killing of Smcy-reactive, TCR-transgenic T cells [24] in vitro with an altered peptide ligand Db-SmcyC2A-SAP tetramer [13]; dose-dependent killing of these T cells with the native Db-Smcy-SAP tetramer is shown in Supplemental Fig. 2F. Injected tetramers can gain access to and bind cognate T cells in spleen and lymph node [44], and can selectively eliminate T cells in vivo [13,16]. In the present study, substantially fewer cognate CTL were elicited by immunization in mice that had been received toxic tetramer injections (Supplemental Fig. 2G), which also supports the notion that CTL precursors are eradicated. In the CTL protection experiments (Fig. 4A), in addition to assessing target survival, we also measured tetramer+ T cells in the spleens of treated mice. As seen in Fig. 4B, in the Db-Uty-SAP group, Db-Uty+ CTL were found at only one-third the frequency observed in control PBS-treated mice. With Db-Smcy-SAP treatment, Db-Smcy+ CTL were always undetectable (i.e., below the background defined by Db-gp33C9M tetramer staining). While these findings were consistent across experiments, the reductions in neither HY specificity were statistically significant, likely because of the high variability in tetramer+ T-cell frequencies across mice following immunization, which has been observed by others [11]. It is worthwhile to note that there was no evidence that administration of either SAP-conjugated tetramer primed, rather than deleted, its cognate T-cell pool. The unintended transfer of peptides from tetramers to endogenous MHC class I molecules could lead to this paradoxical adverse effect [45].

While the sparing of Uty- and Smcy-pulsed splenocytes by administration of cognate toxic tetramers prior to immunization serves as proof-of-principle for this approach, the magnitude of this beneficial effect (46% target survival for Uty; 98% for Smcy) would presumably be insufficient to provide durable allograft protection. Ultimately, to be clinically useful, more complete T-cell deletion will be necessary, potentially accomplished by employing a more dose-intense treatment protocol, or a different toxic moiety. Alternatively, it may be that toxic tetramers in themselves are unable to furnish absolute T-cell tolerance towards minor H antigens, but nonetheless could constitute part of an effective therapeutic regimen towards that end. For example, their pre-transplantation use could reduce CTL precursors sufficiently to make it possible that conventional immunosuppressive therapy could later be tapered or withdrawn without graft harm [46].

In not all pre-transplantation settings will the targeted HY-reactive T-cell population be naïve. Immunodominant CD8+ T cells can be primed by pregnancy with male fetuses in mice (Db-Uty) and humans (A2-Smcy). These T cells are expanded in number relative to their precursors, and in vitro appear functionally similar to memory T cells elicited by allografting [47]. Whether toxic tetramers directed against HY-reactive CD8+ T cells would be equally effective in reducing CTL responses under these conditions will need to be empirically determined. Further, for some multiparous individuals, deletion of such CD8+ T cells might be superfluous. Multiparity can induce prolonged acceptance of male skin grafts in variable proportions of H-2b strains of mice, suggesting that T cells primed by this mechanism are sometimes tolerized [47].

3.5 Toxic tetramers alter the immunodominance hierarchy

As demonstrated previously for other T-cell specificities restricted by H2-Db [13] or H2-Kd [16], the deletional effect of the toxic tetramers in this study was selective. The Db-gp33C9M-SAP tetramer had no effect on HY CTL priming. Db-Uty-SAP did not delete Smcy-reactive T cells, and Db-Smcy-SAP did not delete Uty-reactive T cells. In fact, the opposite phenomenon was observed: administration of a toxic tetramer of one HY specificity appeared to strengthen the CTL responses of its counterpart. The increase in the Db-Smcy+ T-cell population with administration of Db-Uty-SAP is particularly striking. This observation can also be seen in the CTL assay: survival of Smcy-pulsed targets in the Db-Uty-SAP treatment group was considerably less (~10% vs. unpulsed) than that in mice treated with either PBS or the irrelevant toxic tetramer (Fig. 4A). An additional experiment treating mice with Db-Uty-SAP (vs. PBS control alone) reveals the same reciprocal increase in Smcy-reactive CTL numbers and activity (Suppl. Fig. 3). This consistent observation implies that the immunodominance hierarchy between the T-cell populations does not depend on absolute precursor frequency, which is thought to be similar [11], but rather, on competition for APC resources between the two species, a well-documented phenomenon [48,49]. It is conceivable, for example, that under normal circumstances, the major CTL response (Uty) efficiently interacts with and deletes [50] or exhausts APCs presenting male epitopes, thereby restraining priming of the minor response (Smcy) [51]. As one might therefore expect, stronger CTL effector function (as we observed for Db-Uty+ T cells – Fig. 3B), rather than intrinsic proliferative ability, has been correlated with dominant status [52]. Accordingly, in the tetramer-mediated absence of Db-Uty+ CD8+ T cells, Smcy-reactive T cells have unfettered access to APCs and expand more vigorously. This scenario is consistent with reports that immunodomination of one T cell specificity by another can be overcome by exposure to supraphysiologic numbers of APCs during priming [52-54]. Db-Smcy+ CD8+ T cells may be more vulnerable than Db-Uty+ CD8+ T cells to competitive pressures because Smcy binds H2-Db complexes much less efficiently than does Uty peptide, as shown by RMA-S surface class I stabilization assays (our unpublished data, and [11]). Alternatively, the Db-Uty+ and Db-Smcy+ TCRs may bind their cognate pMHC complex with different avidities. Both binding factors have been incriminated in the immunodominance hierarchies of specific CTL [54-57].

For toxic tetramers to be a clinically applicable means of inducing tolerance, the number of T-cell specificities reactive against donor minor H antigens must be limited. Fortunately, this appears to be the case, as there are several mechanisms that greatly restrict the diversity of these alloreactive CTL responses. For some minor H antigens, such as H60, tissue expression is limited to hematopoietic cells. For HY proteins, sequence similarities between peptides derived from some Y chromosome-encoded genes and their X chromosome-encoded paralogs may result in T-cell tolerance [6]. More importantly, for a given antigen, the number of epitopes is severely restricted by immunodominance, which is determined by antigen processing, peptide-MHC binding affinity, TCR availability and other factors. Thus, despite there being 1204 possible nonamer peptides in the Uty protein, the single major focus of CTL responses in B6 mice is the Uty246-254 peptide. The end result of these limiting mechanisms can be observed following the immunization of female B6 mice with H2-matched but otherwise disparate male BALB.B spleen cells; >80% of the CTL responses were directed at just four minor H antigens [58]. Finally, it appears unlikely that all immunodominant CTL reactive against donor minor H antigens contribute to graft failure. A recent review of human studies examining minor H antigens in solid organ transplantation patients revealed that, to date, only HY has appeared to play a significant role in rejection [7].

Of course, if the deletion of major and minor immunodominant HY-reactive CD8+ T cells leads to the expansion of a substantial number of subdominant CTL responses, the need for additional toxic tetramers may become onerous, as the cumulative amount of SAP could be dose-limiting. However, this possibility appears unlikely: Milrain et al. found that, of 54 CTL clones derived from the spleens of male-immunized mice, all recognized either Uty or Smcy [11], so very few other T-cell specificities may emerge. For clinical use, identification of possible subdominant HY-reactive CD8+ T cells in common HLA haplotypes will be essential in assessing feasibility, and conceivably could be accomplished by generating T-cell clones from male-to-female recipients with host-versus-graft or graft-versus-host disease following in vitro, toxic tetramer-mediated elimination of the dominant species. New tetramers resulting from such studies could then be used to investigate the development and impact of these CTL responses in vivo in treated patients.

It is also worthwhile to note that it may not be strictly necessary to delete all HY-reactive CD8+ T cells to achieve tolerance. Repeated injections of the Db-Smcy tetramer into naïve female B6 recipients prolonged the survival of male skin grafts [30]; this treatment regimen was associated with the generation of antigen-unresponsive, regulatory CD8lo T cells capable of suppressing their naïve cognate peers by TGF-β production [59]. Hence, some specificities may be targeted by nondeletional means, and therefore, it may be possible to use a mixture of toxic and non-toxic tetramers to induce stable CD8+ T-cell allotolerance. Ultimately, determining the optimal approach for suppressing a complex mixture of minor H antigen-reactive CD8+ T cell responses – whether by providing signal one alone to induce a non-responsive or regulatory phenotype, or by delivering a toxin to simply eliminate the unwanted effector – will need to be made on an empirical, T-cell specificity-by-specificity basis.

4. Conclusions

Our data show that the selective removal of naïve CD8+ T cells by toxic tetramers can reduce T-cell responses in vivo against two immunodominant HY epitopes. This study is the first to formally demonstrate that CTL killing can be modulated by tetramer-mediated delivery of a toxin, and efficacy in an additional antigenic model strengthens the validity of this approach for specific T-cell deletion. The co-administration of SAP-conjugated Db-Uty and Db-Smcy tetramers to female recipients could provide effective tolerance of MHC-identical male allografts, although concomitant inactivation or suppression of cytotoxic, HY-reactive CD4+ T-cell responses may also be necessary to protect class II+ donor cells [33]. In this work, deletion of the T-cell precursor population was associated with reciprocal changes in immunodominance, so combined toxic tetramer treatment may unmask other H2-Db-restricted subdominant specificities that contribute to anti-HY responses, and subsequently, new tetramers could then be used to eliminate these newly emerged culprits. Ultimately, pre-emptive administration of an optimized panel of toxic (and potentially, non-toxic) tetramers to recipients prior to transplantation could be a useful therapeutic strategy to prevent the induction of CTL responses against multiple minor H antigens that contribute to allograft dysfunction and rejection.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HY is a clinically important minor histocompatibility antigen in allograft rejection

HY-reactive, naïve CD8+ T cells were selectively deleted by toxic tetramers in vivo

Elimination of immunodominant cytotoxic precursors protected cognate CTL targets

Inhibition of one T-cell species amplified responses against the non-targeted epitope

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Maile, Cindy Hensley and Shaomin Tian for guidance and helpful discussions, and Corey Morris and Shaun Steele for excellent animal care. We are also grateful to Larry Arnold, Joan Kalnitsky and Lisa Bixby (UNC-Chapel Hill Flow Cytometry Core Facility) for technical assistance, and Romero Diz for invaluable help with the in vivo CTL assay. This work was supported by an NIH grant (K08 DK082264) and an NCSU-CVM grant to P.R. Hess. The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- APC

Allophycocyanin

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- IP

Intraperitoneally

- IV

Intravenously

- H

Histocompatibility

- LCMV

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- PBSE

Pacific Blue succinimidyl ester

- PBL

Peripheral blood lymphocyte

- PE

Phycoerythrin

- SAP

Saporin

- Yeti

YFP-enhanced transcript for IFN-γ

- YFP

Yellow fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: to be supplied.

References

- 1.Sayegh MH, Carpenter CB. Transplantation 50 years later--progress, challenges, and promises. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2761–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMon043418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opelz G, Dohler B. Effect of human leukocyte antigen compatibility on kidney graft survival: comparative analysis of two decades. Transplantation. 2007;84:137–43. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269725.74189.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson E, Scott D, James E, Lombardi G, Cwynarski K, Dazzi F, et al. Minor H antigens: genes and peptides. Eur J Immunogenet. 2001;28:505–13. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7420.2001.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulmy E. Human minor histocompatibility antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz JC, Campistol JM, Grinyo JM, Mota A, Prats D, Gutierrez JA, et al. Early cyclosporine A withdrawal in kidney-transplant recipients receiving sirolimus prevents progression of chronic pathologic allograft lesions. Transplantation. 2004;78:1312–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000137322.65953.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roopenian D, Choi EY, Brown A. The immunogenomics of minor histocompatibility antigens. Immunol Rev. 2002;190:86–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.19007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dierselhuis M, Goulmy E. The relevance of minor histocompatibility antigens in solid organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:419–25. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32832d399c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells AD, Li XC, Li Y, Walsh MC, Zheng XX, Wu Z, et al. Requirement for T-cell apoptosis in the induction of peripheral transplantation tolerance. Nature Med. 1999;5:1303–7. doi: 10.1038/15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lechler RI, Garden OA, Turka LA. The complementary roles of deletion and regulation in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:147–58. doi: 10.1038/nri1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haudebourg T, Poirier N, Vanhove B. Depleting T-cell subpopulations in organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2009;22:509–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millrain M, Chandler P, Dazzi F, Scott D, Simpson E, Dyson PJ. Examination of HY response: T cell expansion, immunodominance, and cross-priming revealed by HY tetramer analysis. J Immunol. 2001;167:3756–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutis T, Gillespie G, Schrama E, Falkenburg JH, Moss P, Goulmy E. Tetrameric HLA class I-minor histocompatibility antigen peptide complexes demonstrate minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 1999;5:839–42. doi: 10.1038/10563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess PR, Barnes C, Woolard MD, Johnson MD, Cullen JM, Collins EJ, et al. Selective deletion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by MHC class I tetramers coupled to the type I ribosome inactivating protein saporin. Blood. 2007;109:3300–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan RR, Wong P, McDevitt MR, Doubrovina E, Leiner I, Bornmann W, et al. Targeted deletion of T-cell clones using alpha-emitting suicide MHC tetramers. Blood. 2004;104:2397–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penaloza-MacMaster P, Masopust D, Ahmed R. T-cell reconstitution without T-cell immunopathology in two models of T-cell-mediated tissue destruction. Immunology. 2009;128:164–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent BG, Young EF, Buntzman AS, Stevens R, Kepler TB, Tisch RM, et al. Toxin-coupled MHC class I tetramers can specifically ablate autoreactive CD8+ T cells and delay diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:4196–204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson E, Scott D, Chandler P. The male-specific histocompatibility antigen, H-Y: a history of transplantation, immune response genes, sex determination and expression cloning. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:39–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawauchi M, Gundry SR, de Begona JA, Fullerton DA, Razzouk AJ, Boucek MM, et al. Male donor into female recipient increases the risk of pediatric heart allograft rejection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55:716–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90281-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Candinas D, Gunson BK, Nightingale P, Hubscher S, McMaster P, Neuberger JM. Sex mismatch as a risk factor for chronic rejection of liver allografts. Lancet. 1995;346:1117–21. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulmy E, Bradley BA, Lansbergen Q, van Rood JJ. The importance of H-Y incompatibility in human organ transplantation. Transplantation. 1978;25:315–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197806000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gratwohl A, Dohler B, Stem M, Opelz G. H-Y as a minor histocompatibility antigen in kidney transplantation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372:49–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, Baron JL, Wang ZE, Gapin L, et al. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1069–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang B, Maile R, Greenwood R, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA. Naive CD8+ T cells do not require costimulation for proliferation and differentiation into cytotoxic effector cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:1216–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kisielow P, Bluthmann H, Staerz UD, Steinmetz M, von Boehmer H. Tolerance in T-cell-receptor transgenic mice involves deletion of nonmature CD4+8+ thymocytes. Nature. 1988;333:742–6. doi: 10.1038/333742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott DM, Ehrmann IE, Ellis PS, Chandler PR, Simpson E. Why do some females reject males? The molecular basis for male-specific graft rejection. J Mol Med (Berl) 1997;75:103–14. doi: 10.1007/s001090050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billingham RE, Silvers WK. Induction of tolerance of skin isografts from male donors in female mice. Science. 1958;128:780–1. doi: 10.1126/science.128.3327.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billingham RE, Silvers WK. Studies on tolerance of the Y chromosome antigen in mice. J Immunol. 1960;85:14–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laylor R, Dewchand H, Simpson E, Dazzi F. Engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells requires both inhibition of host-versus-graft responses and ‘space’ for homeostatic expansion. Transplantation. 2005;79:1484–91. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000159027.81569.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chai JG, James E, Dewchand H, Simpson E, Scott D. Transplantation tolerance induced by intranasal administration of HY peptides. Blood. 2004;103:3951–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maile R, Wang B, Schooler W, Meyer A, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA. Antigen-specific modulation of an immne response by in vivo administration of soluble MHC class I tetramers. J Immunol. 2001;167:3708–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon IH, Choi SE, Kim YH, Yang SH, Park JH, Park CS, et al. Pancreatic islets induce CD4(+) [corrected] CD25(−)Foxp3(+) [corrected] T-cell regulated tolerance to HY-mismatched skin grafts. Transplantation. 2008;86:1352–60. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818aa43c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millrain M, Scott D, Addey C, Dewchand H, Ellis P, Ehrmann I, et al. Identification of the immunodominant HY H2-D(k) epitope and evaluation of the role of direct and indirect antigen presentation in HY responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:7209–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyznik AJ, Bevan MJ. The surprising kinetics of the T cell response to live antigenic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:4988–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. B cells turn off virgin but not memory T cells. Science. 1992;258:1156–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1439825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenfield A, Scott D, Pennisi D, Ehrmann I, Ellis P, Cooper L, et al. An H-YDb epitope is encoded by a novel mouse Y chromosome gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:474–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markiewicz MA, Girao C, Opferman JT, Sun J, Hu Q, Agulnik AA, et al. Long-term T cell memory requires the surface expression of self-peptide/major histocompatibility complex molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavin MA, Dere B, Grandea AG, 3rd, Hogquist KA, Bevan MJ. Major histocompatibility complex class I allele-specific peptide libraries: identification of peptides that mimic an H-Y T cell epitope. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2124–33. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arsov I, Vukmanovic S. Altered effector responses of H-Y transgenic CD8+ cells. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1423–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.10.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wettstein PJ, Borson ND, Park JG, McNallan KT, Reed AM. Cysteine-tailed class I-binding peptides bind to CpG adjuvant and enhance primary CTL responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:3681–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer KD, Mohrs K, Crowe SR, Johnson LL, Rhyne P, Woodland DL, et al. The functional heterogeneity of type 1 effector T cells in response to infection is related to the potential for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 2005;174:7732–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oehen S, Brduscha-Riem K. Differentiation of naive CTL to effector and memory CTL: correlation of effector function with phenotype and cell division. J Immunol. 1998;161:5338–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obar JJ, Khanna KM, Lefrancois L. Endogenous naive CD8+ T cell precursor frequency regulates primary and memory responses to infection. Immunity. 2008;28:859–69. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drake DR, 3rd, Ream RM, Lawrence CW, Braciale TJ. Transient loss of MHC class I tetramer binding after CD8+ T cell activation reflects altered T cell effector function. J Immunol. 2005;175:1507–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gojanovich GS, Murray SL, Buntzman AS, Young EF, Vincent BG, Hess PR. The use of peptide-major-histocompatibility-complex multimers in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:515–24. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ge Q, Stone JD, Thompson MT, Cochran JR, Rushe M, Eisen HN, et al. Soluble peptide-MHC monomers cause activation of CD8+ T cells through transfer of the peptide to T cell MHC molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13729–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212515299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Besouw NM, van der Mast BJ, de Kuiper P, Smak Gregoor PJ, Vaessen LM, JN IJ, et al. Donor-specific T-cell reactivity identifies kidney transplant patients in whom immunosuppressive therapy can be safely reduced. Transplantation. 2000;70:136–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James E, Chai JG, Dewchand H, Macchiarulo E, Dazzi F, Simpson E. Multiparity induces priming to male-specific minor histocompatibility antigen, HY, in mice and humans. Blood. 2003;102:388–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wettstein PJ. Immunodominance in the T cell response to multiple non-H-2 histocompatibility antigens. III. Single histocompatibility antigens dominate the male antigen. J Immunol. 1986;137:2073–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolpert EZ, Grufman P, Sandberg JK, Tegnesjo A, Karre K. Immunodominance in the CTL response against minor histocompatibility antigens: interference between responding T cells, rather than with presentation of epitopes. J Immunol. 1998;161:4499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loyer V, Fontaine P, Pion S, Hetu F, Roy DC, Perreault C. The in vivo fate of APCs displaying minor H antigen and/or MHC differences is regulated by CTLs specific for immunodominant class I-associated epitopes. J Immunol. 1999;163:6242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willis RA, Kappler JW, Marrack PC. CD8 T cell competition for dendritic cells in vivo is an early event in activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12063–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy-Proulx G, Meunier M, Lanteigne A, Brochu S, Perreault C. Immunodomination results from functional differences between competing CTL. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2284–92. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2284::aid-immu2284>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grufman P, Wolpert EZ, Sandberg JK, Karre K. T cell competition for the antigen-presenting cell as a model for immunodominance in the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response against minor histocompatibility antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2197–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2197::AID-IMMU2197>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kedl RM, Rees WA, Hildeman DA, Schaefer B, Mitchell T, Kappler J, et al. T cells compete for access to antigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1105–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der most RG, Sette A, Oseroff C, Alexander J, Murali-Krishna K, Lau LL, et al. Analysis of cytotoxic T cells responses to dominant and subdominant epitopes during acute and chronic lymphocytic choriomengitis virus infection. J Immunol. 1996;157:5543–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pion S, Christianson GJ, Fontaine P, Roopenian D, Perreault C. Shaping the repertoire of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses: explanation for the immunodominance effect whereby cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for immunodominant antigens prevent recognition of nondominant antigens. Blood. 1999;93:952–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pion S, Fontaine P, Desaulniers M, Jutras J, Filep JG, Perreault C. On the mechanisms of immunodominance in cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to minor histocompatibility antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:421–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi EY, Yoshimura Y, Christianson GJ, Sproule TJ, Malarkannan S, Shastri N, et al. Quantitative analysis of the immune response to mouse non-MHC transplantation antigens in vivo: the H60 histocompatibility antigen dominates over all others. J Immunol. 2001;166:4370–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maile R, Pop SM, Tisch R, Collins EJ, Cairns BA, Frelinger JA. Low-avidity CD8lo T cells induced by incomplete antigen stimulation in vivo regulate naive higher avidity CD8hi T cell responses to the same antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:397–410. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.