Abstract

Most of the newly discovered compounds showing promise for the treatment of TB, notably multidrug-resistant TB, inhibit aspects of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope metabolism. This review reflects on the evolution of the knowledge that many of the front-line and emerging products inhibit aspects of cell envelope metabolism and in the process are bactericidal not only against actively replicating M. tuberculosis, but contrary to earlier impressions, are effective against latent forms of the disease. While mycolic acid and arabinogalactan synthesis are still primary targets of existing and new drugs, peptidoglycan synthesis, transport mechanisms and the synthesis of the decaprenyl-phosphate carrier lipid all show considerable promise as targets for new products, older drugs and new combinations. The advantages of whole cell- versus target-based screening in the perpetual search for new targets and products to counter multidrug-resistant TB are discussed.

Keywords: antibiotic, arabinogalactan, cell envelope, Mycobacterium, mycolic acids, peptidoglycan, tuberculosis

TB is, after HIV/AIDS, the second most common cause of death due to a single infectious agent. Infections by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of the disease in humans, have been estimated by WHO to be 8.7 million new cases during 2011 [201]. Globally, TB is now the leading cause of death for individuals living with HIV, causing one in four deaths. TB claims approximately 1.4 million lives annually and the global number of TB cases is still rising fueled by poverty, the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the emergence of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant strains, resistant to three or more of the six classes of second-line drugs in addition to rifampicin (RIF) and isoniazid (INH) [1]. Countries of the former Soviet Union, provinces in China, India and South Africa have reported the highest proportions of resistance.

It is difficult to obtain quantitative data on annual incidence of disease and death owing to TB at the dawn of the era of chemotherapy. In the prechemotherapy era, death rates were approximately 50–60%. It is thought that in the early 1800s, almost all western Europeans were infected with Mtb and approximately one in four deaths were due to TB. According to reliable estimates by WHO, global incidence in 1992 was 8,029,000 and mortality was 2,708,000, and according to an earlier 1989 WHO report, 1.3 million cases and 450,000 deaths from TB in developing countries occurred in children under the age of 15 years. Thus, there has been no marked improvement in the public health problem of TB over the past 25 years. Incidentally, estimates from 1991 suggested that approximately one-third of the world’s population, approximately 1.7 billion people at the time, was infected with Mtb. However, this was based on tuberculin-positive surveys, a test that is not necessarily specific for Mtb infection.

Streptomycin (STR) was first isolated in 1943 in the laboratory of Waksman at Rutgers University (NJ, USA) and was the first important new antibiotic since penicillin [2]. However, patients on penicillin did not then develop resistance whereas those on STR did. Results showed striking efficacy against TB, albeit with minor toxicity and acquired resistance to the drug. The first randomized trial of STR (double-blind and placebo-controlled) against pulmonary TB was carried out in 1946–1947 by the British Medical Research Council Tuberculosis Research Unit [2]. However, with the emergence of resistance from that and other trials, the standard treatment for pulmonary TB in the 1960s consisted of administering STR for 3 months, and INH and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) for 18 months to 2 years. The 2-year course of treatment was expensive and protracted leading to problems with compliance and, as a result of various trials primarily conducted in India and Africa, the accepted course of treatment in 1970 had become an 8-month regimen consisting of 2 months of STR/INH/RIF/pyrazinamide (PZA), followed by 6 months of thiacetazone (TAC) and INH; this was subsequently reduced to 6 months. The Jindani studies carried out in many centers in east Africa, Zambia and Hong Kong brought together INH, RIF and PZA as the hallmark of treatment of noncomplicated TB and the bedrock of the more recent Directly Observed Treatment – Short course (DOTS) five-point strategy [2].

Historical perspective on association of TB drugs & disruption of the cell envelope of Mtb

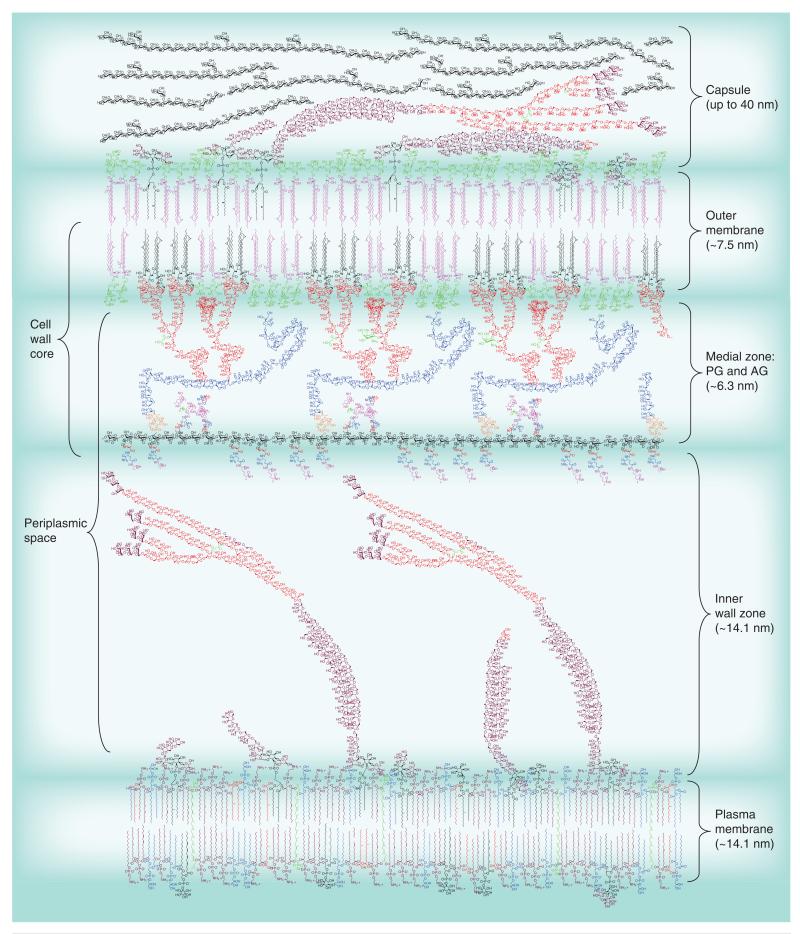

Although unbeknown to many at the time, modern day chemotherapy of TB, whether in the case of first-line drugs or second-line for multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB, relied on compounds that inhibited some aspect of Mtb cell envelope metabolism. Yet, emphasis on specifically targeting the unique cell envelope of Mtb (Figure 1) in the context of the perpetual search for new acceptable products to counter drug-resistant TB has not always been favored. This perception may have arisen from Mitchison’s concept of the 1970s of two different populations of Mtb in sputum (as distinct from culture), one actively replicating and the other persistent [2]. INH, now known to primarily inhibit mycolic acid synthesis, was very effective at rapidly killing the former with much slower killing of the persistent bacilli in a process called ‘sterilizing’ action. However, from what we now know of the cell envelope composition of Mtb and Mycobacterium leprae in vivo, basal ‘cell wall core’ metabolic activity is likely to be maintained throughout the different stages of infection [3,4]. The changes impacting the surface of mycobacteria observed under certain persistence conditions (e.g., hypoxia [5] or inside macrophages [6]), such as microscopic evidence of capsular polysaccha-rides at the interface between the bacterium and the phagosome, all support the emerging evidence of a cell wall structure during infection, including persistence. Mycolic acid cyclopropanation is regarded as important for the persistence of Mtb in mice [7], as is the l,d-transpeptidase LtdMt2 [8]. The importance of peptidoglycan (PG) metabolism is also clearly illustrated by the efficacy of penicillins and clavulanate combinations against persistent bacteria [9].

Figure 1. A depiction of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope.

The cell wall core (also known as mycolyl AG–PG or mAGP) consists of the PG (black with colored peptides extending from it) attached to the mycolate layer (inner leaflet of the outer membrane) via the AG. The galactofuranosyl residues are shown in blue and the arabinofuranosyl residues in red. The mycolic acids attached to the arabinan are shown in black and are in a folded ‘W’ configuration; the pink mycolic acids are attached to trehalose (trehalose monomycolate with a single mycolic acid and trehalose dimycolate with two mycolic acids) and are expected to be found in both leaflets of the outer membrane.

Lipoarabinomannan (arabinofuranosyl residues in red as in AG and mannopyranosyl residues in purple) is shown both in the outer membrane and plasma membrane as is lipomannan. Phospholipids are only shown in the plasma membrane, but are also found in the outer membrane. The capsule is shown containing glucan (black), mannan (purple) and arabinomannan (purple and red). The dimensions of the various layers are from published electron micrographic studies [112-114]. Molecular modeling suggests that the length of the medial zone could be as large as 20 nm; the arabinan and galactan are quite flexible and a very dense contracted configuration is required for the much smaller 6.5-nm medial zone suggested by the electron microscopic studies; this perhaps could change under different growth conditions. The cell wall core (left side of figure) is the primary target discussed in this review. Please see full size image as supplementary Figure 1 online at www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/fmb.13.52.

AG: Arabinogalactan; PG: Peptidoglycan.

Another concern regarding favoring drug development in the context of the cell envelope of Mtb arose from earlier perceptions indicating that drugs targeting the cell wall, notably INH, lessened the efficacy of other drugs used in combination, particularly RIF, rather than acting synergistically, as one may have expected given the potential of these drugs to increase the permeability of the cell envelope to various compounds. However, recent examples of novel inhibitors acting on some aspects of cell envelope synthesis are proving otherwise, such as the known synergistic effect of the benzothiazinone (BTZ) BTZ043 with TMC207 [10] and of SQ109 with TMC207, INH and RIF [11,12]. Notable in that respect are the new InhA inhibitors [13] that increase bactericidal activity when used in combination with INH and RIF, and capuramycin analogs that act synergistically with ethambutol (EMB), INH and SQ109 [14].

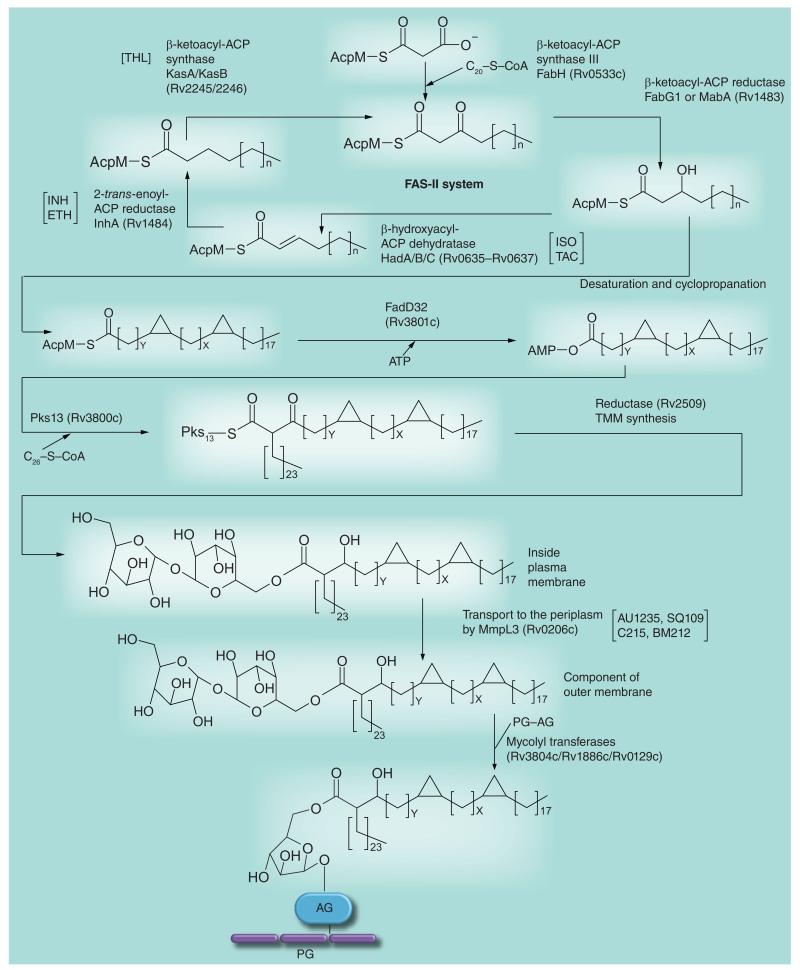

The first useful information on the effects of INH on cell envelope integrity arose from studies by Winder in the 1960s on carbohydrates now known to be inherent components of the cell wall [15]. The accumulation of trehalose and arabinan were notable. Since these carbohydrates are normally acylated with mycolic acids, in the form of trehalose mycolates and mycolylarabinogalactan, a direct effect of INH on mycolic acid synthesis was investigated. INH at 0.1 μg/ml completely inhibited the synthesis of mycolates by actively growing Mtb during 6 h of exposure (for a recent review on INH, see [16]). Takayama and Davidson extended the work of Winder in demonstrating that INH treatment of Mtb led to inhibition of the synthesis of C24 and C26 monounsaturated fatty acids [17]. However, the more recent elegant genetic studies of Jacobs and colleagues identified InhA as the target of INH [18]; InhA is a NADH-dependent specific enoyl-ACP reductase, the rate-limiting step in mycolic acid synthesis by the FAS-II pathway. Sacchettini and colleagues discovered that the actual inhibitor of InhA is an INH-NAD adduct [19]. In 1971, Winder et al. showed that ethionamide (ETH) also acts by inhibiting mycolic acid synthesis [20]. Like INH, ETH inhibits InhA [16]. The major difference between the two is in the lack of cross-resistance; strains resistant to ETH are still sensitive to INH whereas those resistant to INH show increased sensitivity to ETH. Resistance to both is primarily due to mutations that block the specific activation steps of these drugs, and the enzymes involved are different. In the case of INH, a pro-drug, activation involves generation of a range of oxygen and organic intermediates catalyzed by the catalase–peroxidase enzyme, KatG, encoded by katG, the site of the majority of resistant mutations to INH. By contrast ETH is activated by EthA, a FAD-containing enzyme that generates a S-oxide as the active form [21]. Incidentally, pyridomycin, an unusual cyclic depsipeptide isolated from a Streptomyces species and with appreciable antimycobacterial activity, is now known to target InhA [22]. Thiolactomycin (THL) – known since the early 1980s and the first naturally occurring thiolactone with appreciable antibiotic activity, also against mycobacteria – inhibits the subsequent elongation enzymes in the FAS-II mycolic acid pathway, KasA and KasB [23].

As part of these studies in the early 1970s, Winder et al. demonstrated that isoxyl (ISO), a member of the diaryl thiourea class (also activated by EthA), inhibited mycolic acid synthesis [20]. The recent follow-up of those earlier observations resulted in the identification of the dehydration step of the FAS-II pathway as the target of ISO [24].

EMB has been known as an effective anti-TB drug since the early days of chemotherapy and is now a component of one version of short-course chemotherapy involving INH, RIF, PZA and EMB. The earliest effects of treatment of mycobacteria with EMB is inhibition of the synthesis of the arabinan of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) and arabinogalactan (AG) (Figure 1) [25]. As a consequence, the lack of the primary attachment sites of mycolic acids results in the channeling of the mycolate residues to form free lipids, such as trehalose mycolates, which then accumulate. The majority of EMB-resistant mutants map to the embB gene that, as part of the emb operon, is responsible for arabinan polymerization [26].

PZA is a prodrug; pyrazinoic acid is the active form. It appears to inhibit multiple targets in Mtb. In addition to inhibiting trans-translation through binding to the ribosomal protein S1 (RpsA) [27], PZA apparently inhibits the activity of FAS-I [28].

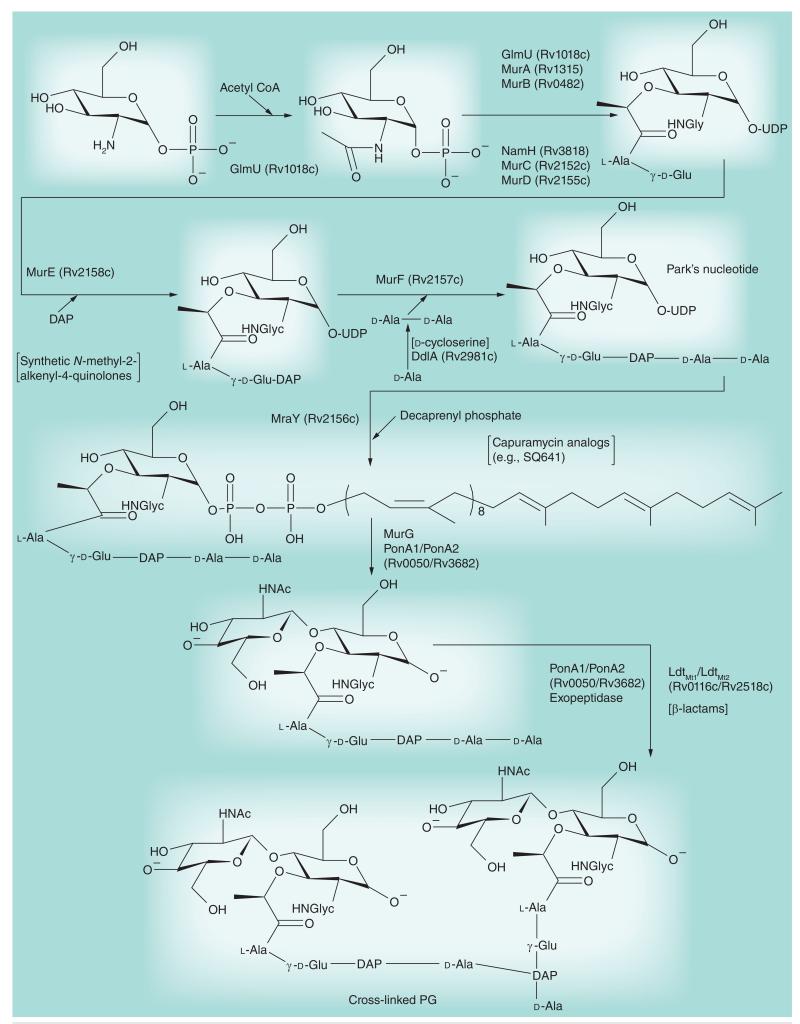

PG synthesis (Figure 1) has undergone a resurgence of interest as a promising target for new approaches to the chemotherapy of TB. Of course, d-cycloserine has long been a useful second-line drug in the treatment of TB and nowadays in the treatment of MDR-TB despite its well-known effects on the CNS. It competitively inhibits the two enzymes in the synthesis of the peptide chain of PG, alanine racemase, which forms d-alanine from l-alanine, and d-alanine:d-alanine synthase in all eubacteria, including mycobacteria [29]. The recent success of penicillins and clavulanate combinations in the treatment of active and latent TB [9] has resulted in a revisitation of the prospects of introducing β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitors into standard TB chemotherapy.

The search for novel drugs & the era of target-based approaches

Target-based screens

The need to address the issues of multidrug resistance and persistent infection and therefore discover drugs with novel modes of action has led investigators to search for inhibitors targeting enzymes deemed specific and essential for the replication and persistence of Mtb. Known as target-based screening, this approach was rendered possible by advances in the genomics and molecular genetics of mycobacteria in the late 1990s that enabled the identification, functional characterization and preliminary genetic validation of potential targets. The hope was that the remarkable results yielded by this approach in the fields of retroviral and cancer treatments would similarly apply to TB drug discovery. Following the selection of a target of interest, the goal was to develop inhibitors that would kill Mtb through their action on the targeted enzyme (or transporter). Several independent and complementary approaches were used toward this goal including the screening of chemical libraries for compounds inhibiting the target’s activity in vitro, structure-, ligand- and fragment-based design [30-32]. The major advantage of the target-based approach is that the compound series identified as inhibitors of a particular target can be rationally optimized through medicinal chemistry to improve activity and molecular selectivity while minimizing the risk of side effects. Although careful validation of the mode of action of the optimized compounds in whole cells is required to ensure that they remain on-target, this approach is of enormous value in progressing hit-to-lead and to candidate drugs. Because of their essentiality and involvement in mycobacterial-specific metabolic processes, many cell envelope biosynthetic enzymes appeared to be good candidates for this approach and were pursued accordingly [33].

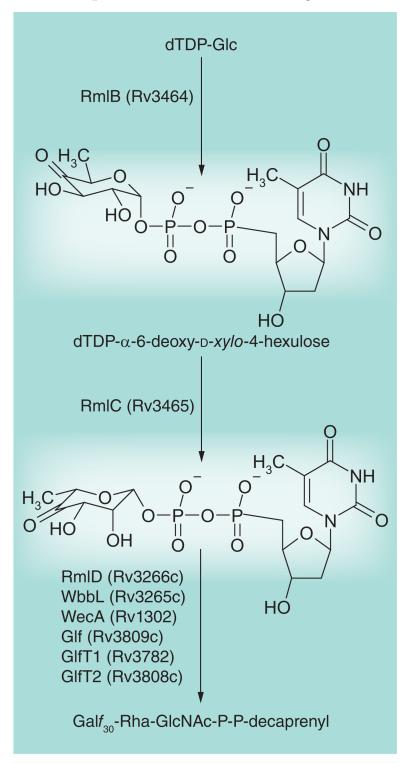

Figures 2-6 present aspects of the cell wall biosynthetic pathways that have been targeted in recent years. RmlC (Figure 2) is a key biosynthetic enzyme (dTDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose 3,5-epimerase) involved in the formation of dTDP-rhamnose, thereby providing the rhamnosyl residue found in the linker region by which AG is attached to PG (see Figures 1 & 3). The enzyme was shown to be essential and an assay was developed that is suitable for high-throughput screening ([34] and references therein). The screen yielded four compounds with 0.12–1.25 μM Ki values and 9–19 μg/ml MICs. Thus far, further optimization of these compounds has not appeared to be feasible. A second enzyme, GlmU (Figure 4) is involved in the formation of UDP–GlcNAc, which is required for synthesis of both PG (Figure 4) and the linker region (Figure 3). As with RmlC, the enzyme was shown to be essential [35]. An assay suitable for high-throughput screening of the N-acetyltransferase domain of the enzyme (the enzyme has both a C-acetyl transferase and an N-terminal uridylyl transferase domain) was developed, and NIH-sponsored screening was performed [202], which was later analyzed for optimization of hits [36]. Other inhibitor screening assays performed in our laboratories include that against Glf, the enzyme that converts UDP-Galp to UDP-Galf (Figure 2), which was performed using in-house chemical libraries. No reliable hits were obtained; however, a preliminary hit, which on further experiment did not reproducibly inhibit Glf, was active against whole Mtb at submicromolar concentrations [37]. Work on this agent, a nitrofuranylamide, continues [38,39]. Also, virtual screening against RmlD, the dTDP-6-deoxy-l-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase (Figure 2), resulted in the identification of several inhibitors of this enzyme that had very modest activity against Mtb in culture (20–200 μg/ml) [40].

Figure 2. Biosynthesis of cell wall rhamnosyl residues and the formation of lipid-linked galactan.

This figure focuses on the targeted enzymes, RmlC, RmlD and Glf, but includes all of the enzymes involved in making the linker and galactan regions of arabinogalactan. As with the early steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, a large number of potential drug target enzymes (eight in total) are present. RmlA–D are soluble enzymes involved in making dTDP-Rha; Glf is a soluble enzyme that makes UDP-Galf. WbbL, GlfT1 and GlfT2 are glycosyltransferases that use the dTDP-Rha and UDP-Galf, respectively, to attach Rha and Galf to the lipid intermediate shown. WecA is a GlcNAc-phosphate transferase that attaches GlcNAc-1-P to decaprenyl phosphate. For further details of the pathway, see [33].

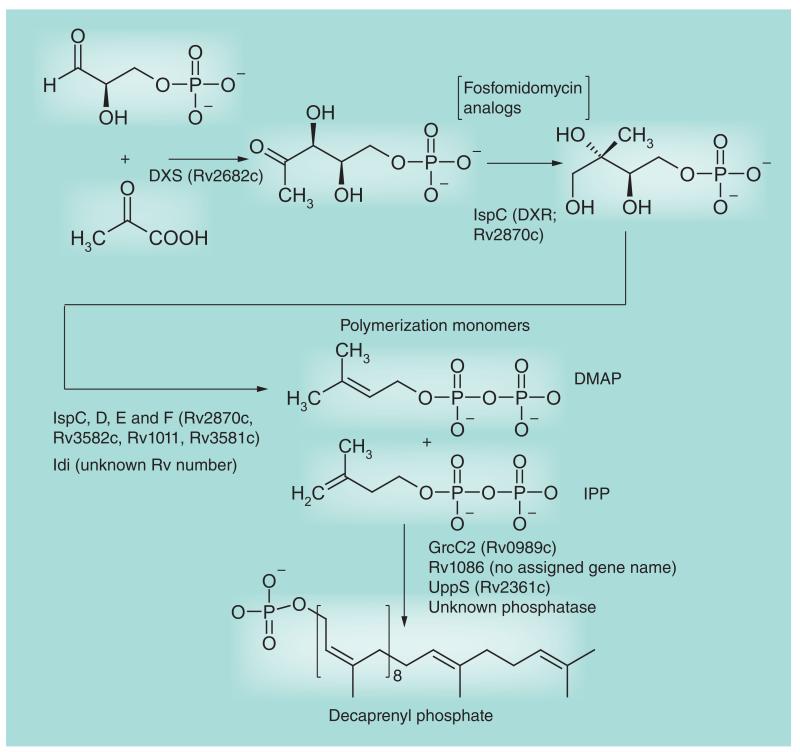

Figure 6. Decaprenyl phosphate biosynthesis.

This figure focuses on the targeted enzyme DXR (IspC). The first six enzymes, including DXR, are involved in the formation of polymerization precursors DMAP and IPP via the non-mevalonate pathway. The later enzymes catalyze the polymerization and dephosphorylation reactions. Decaprenyl phosphate is used for arabinan, arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

DMAP: Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; DXS: 1-deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate; IPP: Isopentyl pyrophosphate.

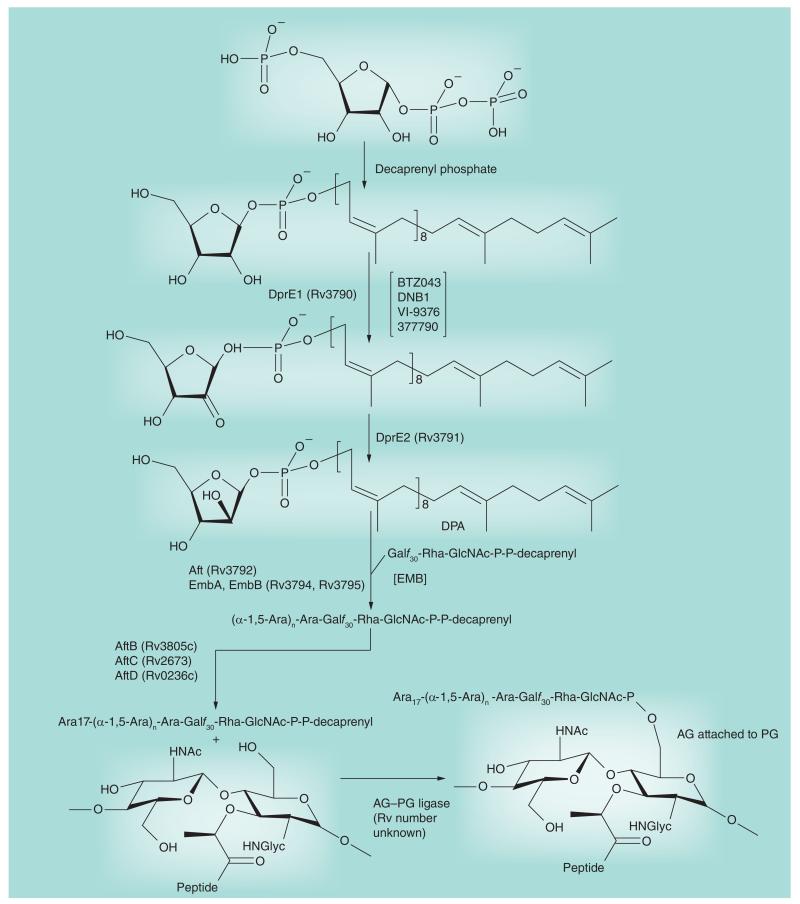

Figure 3. Arabinosyl biosynthesis.

This figure focuses on the targeted enzymes DprE1 and EmbA, B and C. The activated donor of arabinosyl residues, decaprenyl phosphoryl arabinose, is formed from the nucleotide biosynthetic intermediate phosphoribose pyrophosphate in four enzymatic steps beginning with the transfer of phosphoribose to decaprenyl phosphate. Decaprenyl phosphoryl arabinose is then used as the arabinosyl donor by the arabinosyltransferases. The final product of this figure, AG attached to PG, is then mycolylated (see Figure 5) to form the complete cell wall core (mAGP). The sites of action of the inhibitors mentioned in this review are indicated between square brackets.

AG: Arabinogalactan; EMB: Ethambutol; PG: Peptidoglycan.

Figure 4. Peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

This figure of the pathway focuses on enzyme targets discussed in this review. The pathway divides into the cytoplasmic formation of Park’s nucleotide (see top and middle of figure) and then the formation of the membrane-bound decaprenyl diphosphate Mur pentapeptide followed by polymerization, cross-linking and trimming. The early enzymatic steps forming Park’s nucleotide appear to be fertile for drug targeting, but as discussed in the text, they have only yielded d-cycloserine, although new work continues. The phospho-N-acetylmuramyl pentapeptide translocase MraY is thought to be the target of capuramycin analogs currently undergoing preclinical development. The cross-linking event late in the pathway is the target for the β-lactams that are now receiving attention for use against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. For further details on the formation of peptidoglycan, see [33].

DAP: Diaminopimelic acid; Glyc: Glycolate; PG: Peptidoglycan.

As detailed below, other cell envelope biosynthetic processes are currently being pursued as targets for their potential to kill MDR/extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Mtb isolates or to address the issues of Mtb persistence and reactivation. Targets of interest not only include catalytic enzymes involved in the building of all major cell wall core constituents (PG, AG and mycolic acids), but also components of the translocation and regulatory machineries associated with these pathways. Interestingly, enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of as yet untargeted glycoconjugates and outer membrane lipids are also among the recently proposed or actively screened targets.

Owing to their key role in the final assembly steps of mycolic acids, the condensase enzyme Pks13 and associated transferase FadD32 (Figure 5) are the objects of intensive drug development efforts [41,42]. Gene knockdown experiments identified FadD32 as a particularly vulnerable target whose inhibition caused immediate cell death both in vitro and inside macrophages [43]. A high-throughput assay was recently developed for this enzyme [44]. The mycolyltransferases of the antigen 85 complex (Figure 5) also appear to be promising targets owing to the pivotal role they play in the structural integrity of the mycobacterial outer membrane and their extra-cellular location, which should make them more accessible to inhibitors. The crystal structures of all three antigens have been solved, high-throughput screening assays have been developed and efforts have begun to test substrate analogs as potential inhibitors of these enzymes and whole mycobacterial cells (for a review, see [45]). Recently, small molecule Ag85C binders identified by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy demonstrated antimycobacterial activity against Mtb in culture and inside macrophages in the 100 μM range [46].

Figure 5. Mycolic acid biosynthesis.

This figure of the pathway focuses on targets discussed in this review. The meromycolate carbon chain is formed via the FAS-II system (top of figure). The introduction of the double bonds is not yet understood; it may involve an isomerization event during FAS-II elongation or occur (as shown in the figure) after formation of the carbon chain. After cyclopropanation and (not shown in the figure) formation of keto and methoxy groups, the meromycolate is activated and condenses with C26-S-CoA; the C26-S-CoA is formed from the FAS-I fatty acid elongation system. After reduction, the now mature mycolic acid is attached to trehalose to form TMM by an unknown enzyme and mechanism. It is then transported to the cell envelope outside the plasma membrane and attached to AG by a transport mechanism involving MmpL3 and the mycolyl transferases, respectively. For further details of the pathway, see [33]. The sites of action of the inhibitors mentioned in this review are indicated between square brackets. AG: Arabinogalactan; ETH: Ethionamide; INH: Isoniazid; ISO: Isoxyl; PG: Peptidoglycan; TAC: Thiacetazone; THL: Thiolactomycin; TMM: Trehalose monomycolate.

d-cycloserine, a drug once used in the clinical treatment of TB, acts as a competitive inhibitor of the d-alanine:d-alanine ligase of Mtb (DdlA; Figure 4) thereby inhibiting PG synthesis. With the goal of developing more effective inhibitors of this enzyme, the crystal structures of DdlA under its apo form and in complex with d-cycloserine were recently solved [47]. Other efforts to kill Mtb though the inhibition of PG biosynthesis have focused on a series of synthetic N-methyl-2-alkenyl-4-quinolones showing IC50 values in the range of 100 μM against the Mtb MurE ligase (Figure 4) in vitro and 5–25 μg/ml MICs against Mtb in culture [48].

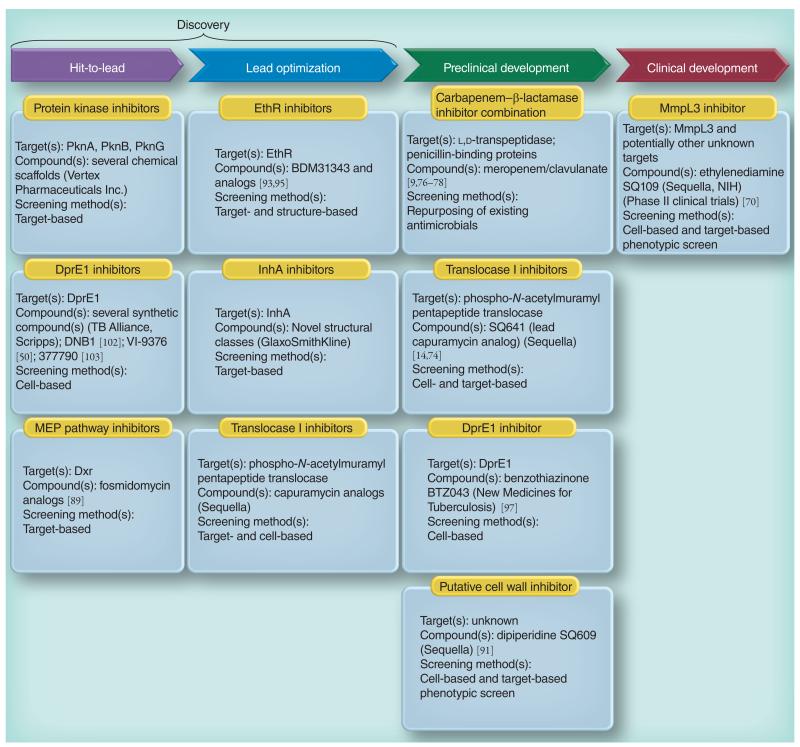

The growing interest surrounding the eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinases of Mtb as putative drug targets stems from the finding that these enzymes may not only play a role in modulating the signaling systems of infected host cells, but also pivotal regulatory functions in the control of cell division and cell envelope biogenesis in mycobacteria (for a review, see [49]). PknA and PknB in particular are essential for Mtb growth. These enzymes and other members of the Ser/Thr kinase family were shown to regulate the activity of multiple enzymes and transporters involved in the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, PG, AG, LAM and phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIMs) through phosphorylation [49]. The Mtb Ser/Thr kinases only share approximately 30% sequence identity with their counterparts in humans suggesting that it may be possible to design inhibitors specific to the mycobacterial enzymes. Accordingly, libraries of compounds were screened against PknA or PknB in vitro and some inhibitors with IC50 values in the nanomolar range and MICs against Mtb in the micromolar range were identified [50-53]. However, preliminary evidence suggests that the treatment of Mtb cells with some of these inhibitors leads to the inhibition of multiple targets [50,52]. The pursuit of Ser/Thr protein kinases as targets presents the unique advantage owing to multiple libraries of small molecule kinase inhibitors being developed in the last two decades in the context of anti-cancer drug research. The Working Group on New TB Drugs [203] reports several other compounds currently under development at Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. (MA, USA) showing activity against PknA, PknB and/or PknG in vitro and 0.1–10 μg/ml MICs against Mtb (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Global TB drug pipeline showing the cell envelope-related inhibitors under development.

See text and the Working Group for New Drugs, Stop TB Partnership [203] for details.

Another regulatory system of interest in the context of drug development is the two-component transcriptional regulator PhoP–PhoR (Rv0757–Rv0758), which regulates multiple virulence-associated processes in Mtb including the biosynthesis of Mtb-specific acyltrehaloses known as sulfatides or sulfolipids, diacyltreha-loses and polyacyltrehaloses [54-59]. All genes from Mtb strain H37Rv carry an ‘Rv number’ and are numbered sequentially along the chromosome – the gene numbering system of Mtb strain H37Rv is used throughout this review. A mutation in the phoP gene of Mtb H37Ra accounts for the inability of this virulent Mtb strain to produce sulfolipids, diacyltrehaloses and polyacyltrehaloses [60]. To the best of our knowledge, no inhibitors of PhoP-PhoR have yet been reported.

Glycosyltransferases of the GT-C superfamily play pivotal roles in the biogenesis of mycobacterial cell envelope glycoconjugates (for reviews, see [29,45]). The fact that most of them are essential for Mtb growth and that three arabinosyl transferases of this superfamily (EmbA, EmbB and EmbC) (Figure 3) are the targets of EMB has stimulated the design of innovative assays for inhibitor screening against these enzymes [45].

Novel biosynthetic pathways that are currently being targeted in the context of drug development include that of α-1,4-glucans and that of PDIM and closely related phenolic glycolipids [45]. Although not essential for growth, PDIM and phenolic glycolipids contribute to the ability of Mtb to replicate intracellularly and in vivo and modulate a number of host immune functions. These lipids also play important roles in the permeability barrier of the cell envelope [61] suggesting that compounds inhibiting their synthesis could synergize with or potentiate existing anti-TB drugs. Similarly, two enzymes involved in the formation of the α-1,4-glucans of Mtb, namely the branching enzyme GlgB and the α-1,4-glucan:maltose-1-phosphate maltosyl transferase GlgE, may represent good targets for drug development since their inactivation will result in the lethal accumulation of maltose-1-phosphate [62,63].

Finally, another recently proposed innovative approach to TB drug development consists of searching for inhibitors capable of blocking the major protein secretion machineries of Mtb. Since many cell envelope biosynthetic enzymes and transporters need to be exported for activity, this strategy is expected to negatively impact multiple cell envelope-related processes [64]. In particular, inhibitors of the twin-arginine trans-location system, which exports proteins that are prefolded within the cytoplasm, would be of great benefit if one assumes that by preventing the secretion of the major β-lactamase (BlaC) of Mtb, such inhibitors may significantly increase bacterial susceptibility to β-lactams.

As noted in several recent reviews [30,65], the screening of inhibitors targeting essential Mtb enzymes, whether related to cell envelope bio-genesis or to other physiological processes (e.g., cofactor biosynthesis, central carbon metabolism and transcriptional regulators, among others), has not yet yielded a single drug in clinical trials [30,31,33]. The reasons for this are most likely several fold. While lack of penetration across the Mtb cell envelope is often thought to be the primary cause of the disappointing MIC values of identified hits, other reasons may include the inactivation of the compounds by bacterial enzymes or their active efflux. The untoward physicochemical properties combined with the limited structural diversity of the libraries of compounds used in the high-throughput screens were proposed as other possible reasons for the failure of this approach [65]. Another important consideration is the vulnerability of the target, in other words, how much inhibition of a particular target in whole cells is required to achieve growth arrest. In this respect, drug targets have been found to vary greatly in their sensitivity to inhibition [66-68]. Therefore, rigorous validation of the target using chemical and/or genetic approaches (e.g., gene knockdown and protein depletion strategies) remains an important prerequisite for increasing the likelihood of success. Finally, it is important to consider the technical challenges that may limit the usefulness of cell envelope biosynthetic enzymes as viable targets. These include the difficulty of producing soluble and active enzymes in sufficient yields for high-throughput screening and X-ray crystallography (many of them are integral or peripheral membrane proteins), in addition to the complex nature of the catalytic substrates that are often poorly water-soluble and the lack of commercial availability of the substrates required for screening. While the specificity of the cell envelope pathways targeted by many old and new antimycobacterial drugs is generally considered as one of their strengths, it also clearly represents an obstacle to the development of high-throughput screens.

Other target-based approaches

The limited success met by the target-based screening projects described above, however, should not undermine the potential of target-based approaches as a whole. Indeed, such approaches are not limited to target-based screens and other strategies have successfully been pursued. One such strategy consists of the design and synthesis of derivatives of existing drugs targeting an enzyme of interest in Mtb or in another microbial pathogen. A number of examples, some of which are described below, illustrate the power of this approach. Another strategy has consisted of employing a gene reporter system to identify compounds inhibiting cell envelope biosynthesis [69]. Finally, a less developed yet promising approach has consisted of structure-based drug design.

Derivatives of existing drugs targeting an enzyme of interest

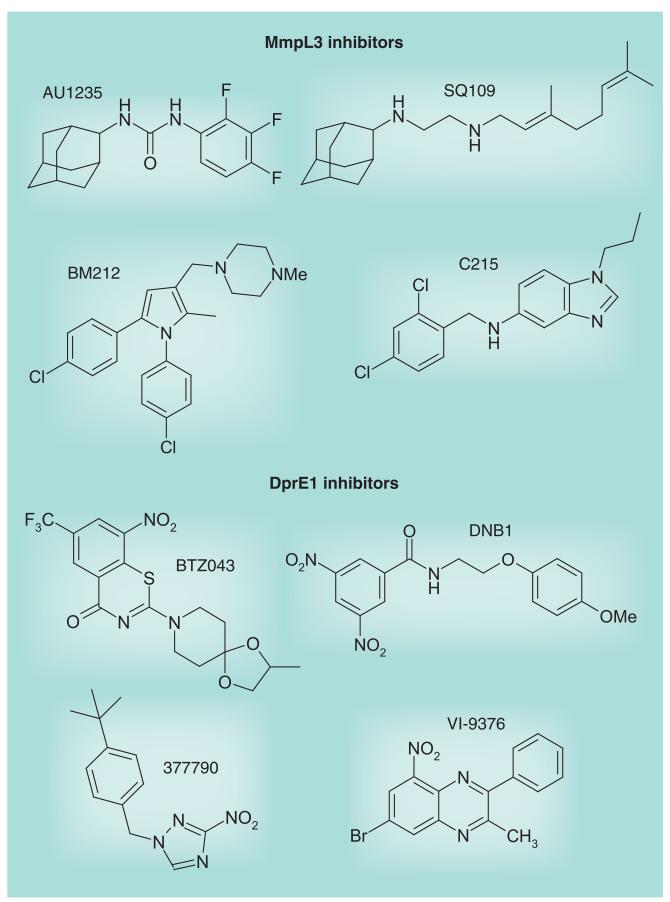

Attempts to generate more potent derivatives of EMB using combinatorial chemistry has led to the synthesis of SQ109 (Figure 8) [70]. SQ109 has good selectivity and improved efficacy over EMB in mouse models of TB infection. It displays synergistic activity both in vitro and in vivo with most of the drugs currently used in the clinical treatment of TB, favorable pharmacokinetics properties and has a remarkable property to concentrate in lung tissues [71]. Although designed to be a derivative of EMB and therefore an inhibitor of AG synthesis, recent studies have indicated that the mode of action of SQ109 is primarily inhibition of mycolic acid translocation [72]. SQ109 is currently undergoing Phase II clinical trials (Figure 7).

Figure 8. Structures of MmpL3 and DprE1 inhibitors.

The synthesis of capuramycin analogs as inhibitors of bacterial phospho-N-acetylmur-amyl pentapeptide translocases (EC.2.7.8.13; MraY; Figure 4) has led to the identification of several analogs with potent activity against Mtb (MIC of 2–4 μg/ml against drug-susceptible and MDR isolates) and several other mycobacterial pathogens both in vitro and in vivo [14,73,74]. Although their mode of action has not yet been confirmed in whole Mtb cells, these inhibitors are thought to inhibit a very early stage of PG biosynthesis. One of these analogs, SQ641, is now at the stage of preclinical development (Figure 7).

Resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpfs) are required to restore the culturability of non-replicating persistent bacilli [75]. Mtb has five rpf-like genes with partially overlapping activity in vitro and in vivo, which are all highly induced during resuscitation. The mechanism through which Rpf proteins stimulate cell reactivation and growth is still unclear, but the fact that their structures share common features with the so-called ‘lysozyme-like’ fold suggests that they may act as cell wall hydro-lyzing enzymes, specifically lysozymes or lytic transglycosylases, and therefore participate in the remodeling of PG that occurs during cell division [75]. Alternatively or in addition, it was proposed that the muropeptides released as a result of the action of Rpf proteins may act as signaling molecules in the host or stimulate the Mtb Ser/Thr protein kinase PknB (see above) to indirectly regulate cell envelope biosynthesis and cell division. Structural similarity between the conserved catalytic domain of Rpfs and that of cell wall lytic enzymes has prompted a search for Rpf inhibitors based on known inhibitors of the latter proteins. Nitrophenylthiocyanate derivatives were tested and found to inhibit the mycobacterial purified Rpfs. While devoid of activity against acute TB in vivo, some of them appear to have the ability to impair the resuscitation of dormant Mtb cells both in vitro and in mice [75]. Nitrophenylthiocyanate derivatives may thus represent a promising new scaffold for drugs capable of controlling persistent Mtb bacilli.

Further emphasizing the potential of PG as a target to kill persistent and MDR bacilli, the combination of two US FDA-approved drugs, meropenem (a β-lactam inhibiting PG cross-linking; see Figure 4) and clavulanate (a β-lactamase inhibitor) was shown to be effective against replicating and nonreplicating (anaerobically grown) Mtb, including XDR clinical isolates, in vitro [9]. This combination also showed some modest activity in a mouse model of infection (Figure 7) [76]. The penicillin-binding proteins responsible for the (d,d) 4→3 interpeptide bonds of bacterial PG are the usual sites of action of β-lactams (Figure 4). Mycobacterial PG, however, is cross-linked with both (d,d) 4→3 and (l,d) 3→3 linkages, the latter being associated with β-lactam resistance in various bacteria and predominating throughout the different stages of growth of Mtb [77]. Two l,d-transpeptidases involved in the 3→3 cross-linking of PG have been identified in Mtb, LdtMt1 (Rv0116c) and LdtMt2 (Rv2518c) [8,78]. LdtMt1 is susceptible to meropenem and other carbapenems [78]. Disruption of LdtMt2 negatively impacts virulence and increases the susceptibility of Mtb to amoxicillin–clavulanate both in vitro and during the chronic phase of infection [8]. The structure of LdtMt2 was recently determined and drugs targeting this novel target are being sought [79]. Altogether, the results of these studies suggest that a combination of l,d-transpeptidase inhibitors, clavulanate and classical β-lactams could effectively target replicating and persistent bacilli.

In search of novel InhA inhibitors (Figure 5), particularly compounds that would not require activation by KatG, Vilcheze and Jacobs screened a library of 300 small molecules that had showed activity against the Plasmodium falciparum enoyl reductase against whole Mtb cells and identified one compound (CD117) that, while nontoxic to eukaryotic cells, was bactericidal against drug-susceptible and drug-resistant Mtb, including a clinical isolate carrying a mutation in katG [16]. Other studies focused on the design of INH and triclosan derivatives, some of which displayed greater activity than INH against Mtb H37Rv in vitro, including Mtb ΔkatG [80-83]. Finally, novel structural classes of InhA inhibitors are reported by the Working Group on New TB Drugs to be in the lead-optimization phase (Figure 7) [203].

Analogs of THL, ISO and TAC were synthesized in the context of structure–activity relationship studies, some of them with improved MICs against Mtb in culture [84-88]. The fact that some of the ISO and TAC analogs inhibited mycolic acid biosynthesis in whole cells suggests that they still target the dehydratase component of the FAS-II system (Figure 5) [24,87].

Decaprenyl phosphate is a key carrier molecule for the synthesis of AG, PG, polar forms of phosphatidylinositol mannosides, lipomannan, LAM and glycoproteins [29,33]. The discovery that decaprenyl phosphate synthesis in Mtb proceeds through the methylerythritol phosphate pathway, which has no homolog in humans, has provided stimulus for the characterization and identification of inhibitors of the relevant enzymes. Fosmidomycin, a phosphonate antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces lavendulae, is a competitive inhibitor of the second enzyme of the pathway, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR; IspC; Figure 6). It is currently in clinical studies for the treatment of malaria in humans. Several derivatives of this drug and its acetyl derivative FR900098 have been synthesized and tested against various bacterial species [89]. Promising results on Mtb were recently obtained with lipophilic prodrug analogs of these two compounds [90] (Figure 7). Importantly, the availability of several crystal structures of the Mtb DXR enzyme and DXR–fosmidomycin complexes has facilitated the structure-based design of more potent analogs. This information and the recent advances in identifying inhibitors, developing assays and elucidating the structure and kinetics of the six other enzymes of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway in different species are likely to stimulate more target-based screening against the corresponding Mtb enzymes in the near future [89].

Use of a gene reporter system to identify inhibitors targeting the cell envelope

Alland et al. reported on the promoter of a gene operon of Mtb (iniBAC) that was strongly and specifically induced by a broad range of inhibitors of cell wall biosynthesis [69]. This induction phenotype led to the development of a target-based phenotypic screening assay wherein the iniBAC promoters fused to the luciferase gene and expressed in Mtb, serving as a reporter system for compounds inhibiting the synthesis of major cell envelope constituents. This system was used in the discovery of SQ109 [70]. More recently, it was used to screen dipiperidine compounds, one of which (SQ609) is now in preclinical development (Figure 7) [91]. The mode of action of SQ609, however, has not yet been reported.

Structure-based drug design

ETH, like ISO and TAC, is a prodrug that require S-oxidation of its thiocarbonyl moiety by the flavin-containing monooxygenase EthA for antimycobacterial activity [21]. Expression of ethA in Mtb is under control of the EthR repressor. An innovative approach that was successfully taken to improve the sensitivity of Mtb to ETH and other thiocarbamides and, therefore, the tolerability of these drugs has been to develop inhibitors of EthR using either a structure-based approach or by screening inhibitors capable of preventing the interaction of EthR with DNA [92,93]. Two compounds, BDM31343 [93] and 2-phenylethyl butyrate [92], were identified that significantly increased the susceptibility of Mtb to ETH in vitro. BDM31343 also boosted the potency of ETH in infected mice [93]. As expected, 2-phenylethyl butyrate also enhanced the inhibitory effects of ISO and TAC against axenically grown Mtb [94]. More potent analogs of BDM31343 with improved pharmacokinetic profiles were recently synthesized (Figure 7) [95].

Whole-cell screening efforts identify inhibitors targeting novel aspects of cell envelope biogenesis

The difficulty of identifying compounds whose inhibitory activity against purified targets translated to whole Mtb cell activity led many investigators in the field to return to whole-cell screening strategies. All currently used antibacterial drugs were discovered using whole-cell screening, highlighting the importance of this approach. Compared to target-based approaches, one of the major advantages of cell-based screens is the fact that they select for antibacterial activity on the outset thereby addressing the issues of target vulnerability and compound penetration across the mycobacterial cell envelope early on. Another significant advantage of cell-based screens is that they offer the possibility of identifying compounds that kill Mtb through the inhibition of multiple targets thereby reducing the risk for the development of resistance. An important consideration while performing whole-cell screening, however, is the condition used for culturing Mtb that should mimic the in vivo biology of replicating or persistent bacilli as closely as possible. Failure to do so may lead to the identification of compounds devoid of activity against Mtb in vivo because the metabolic pathways targeted in the in vitro-grown bacterium may not be active during host infection. A now classic example of this was the report by Pethe et al. of pyrimidine–imidazole compounds showing activity against Mtb exclusively in the presence of glycerol, a carbon source apparently not used or not available to Mtb in mouse lungs [96]. In the absence of a consensus as to the conditions under which cell-based screening should be performed, various models and screening methods are currently being used [30]. While required to drive the lead-optimization process, the elucidation of the target of promising compounds identified in a whole-cell screen can also be an issue, particularly when the mode of action of the compounds involves more than one target. However, a variety of biochemical and ‘omics’ methodologies are now available to identify the molecular targets of inhibitors of interest. Our study of the mode of action of ISO and TAC on mycolic acid biosynthesis, for instance, illustrates how macromolecular analyses of drug-treated cells may help identify the target of an inhibitor by revealing the build-up of its direct substrate [24]. Most recent successes in the field of TB drug discovery have used forward chemical genetics based on resistant mutant generation followed by whole-genome sequencing to elucidate modes of action.

In 2009, Makarov et al. reported on the identification of bactericidal compounds of the BTZ class with MICs in the range of 1–30 ng/ml against Mtb, including MDR and XDR Mtb isolates [97]. BTZ compounds were mostly active against replicating bacilli implying that they blocked a critical step of the active metabolism of the bacterium. The lead compound, BTZ043, was shown to be very active in the murine model of infection [97] and is currently in the late stages of preclinical development (Figure 7). The screening of Mycobacterium smegmatis transformants expressing mycobacterial genomic libraries for clones with increased resistance to the inhibitor, and whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous-resistant mutants of M. smegmatis, Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mtb identified dprE1 (Rv3790) as the gene involved in BTZ resistance. Together with DprE2 (Rv3791), DprE1 catalyzes the epimerization of decaprenylphosphoryl ribose to decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose, the only known arabinose donor in the building of the arabinan domains of AG and LAM. Direct inhibition of the epimerization reaction was confirmed biochemically using membrane preparations from M. smegmatis [97] and more recently using the purified M. smegmatis enzyme [98]. BTZ043 was shown to act as a suicide substrate that is converted to a highly reactive nitroso derivative by DprE1, which then specifically reacts with a Cys residue at position 387 in the active site of the enzyme to form a covalent complex [98,99]. Crystal structures of the M. smegmatis and Mtb DprE1 proteins in their native form and in complex with BTZ043 and other BTZ derivatives were recently reported [100,101]. Interestingly, independent whole-cell screens carried out on Mtb in vitro and ex vivo identified three other series of nitro-aromatic compounds, the dinitrobenzamide DNB1 [102], the nitrobenzoquinoxaline VI-9376 [50] and the nitro-triazole 377790 [103], as potent inhibitors of DprE1 (Figures 3, 7 & 8). Docking experiments with DNB1 and VI-9376 indicated that both compounds fit in the BTZ043-binding site of DprE1 and generate the same key interactions observed for BTZ043 [100]. Other (unpublished) DprE1 inhibitors are reported by the Working Group on New TB Drugs to be in the hit-to-lead phase (Figure 7) [203].

In another study, the screening of approximately 12,000 compounds from a commercial library against axenically-grown Mtb H37Rv led to the identification of a novel bactericidal urea derivative [1-(2-adamantyl)-3-(2,3,4-trifluorophenyl)urea; compound #AU1235] (Figure 8) with an MIC of 0.1 μg/ml (0.3 μM) [104]. AU1235 was similarly active against MDR clinical isolates of Mtb suggesting that it targeted a novel biological function. Metabolic studies indicated that AU1235 abolished the translocation of mycolic acids (under the form of trehalose monomycolates) from their cytoplasmic or membrane-associated site of production to the periplasm where they can then be transferred onto AG or used in the formation of the outer membrane trehalose dimycolates (cord factor). Whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous resistant Mtb mutants followed by genetic validation experiments identified the inner membrane transporter MmpL3 as the target of AU1235 (Figure 5), thereby uncovering one of the key components of the long sought mycolic acid translocation machinery [104]. Further genetic knockout and knockdown experiments finally confirmed MmpL3 as essential for mycobacterial growth and showed that downregulating the expression of this transporter in M. smegmatis recapitulated the phenotypic effects of AU1235 treatment. That MmpL3 did not serve as an efflux pump for AU1235 was confirmed by drug accumulation studies performed in the spontaneous-resistant and -susceptible Mtb strains. Recently, an independent whole-cell screen against Mtb in culture yielded another potent inhibitor of MmpL3, the benzimidazole C215 (N-[2,4-dichlorobenzyl]-1-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-5-amine) (Figure 8) [103]. Finally, determination of the mode of action of two previously identified inhibitors of Mtb, the drug candidate SQ109 (Figure 7) [72] and BM212 (Figure 8) [105], revealed that both compounds also inhibit the activity of MmpL3 in whole Mtb cells. The reason why so many chemically unrelated small molecules inhibit the same target is unclear at present and will require a detailed investigation of their molecular mechanism(s) of action. In terms of structure–activity relationship, the relatively high tolerance of the AU1235 and SQ109 series to structural changes suggests that their binding site must show little specificity except for requiring the presence of large hydrophobic groups [71,106,107]. Alternatively, this tolerance may reflect the fact that these compounds have more than one lethal target in Mtb.

Reflecting on the fact that DprE1, MmpL3 and the ATP synthase [108] were the only three novel targets identified by whole-cell screens coupled to forward chemical genetics since the renewed interest in this approach in the mid-2000s, Stanley et al. suggested that these targets may be more ‘druggable’ and/or more amenable than other proteins to the generation of spontaneous resistant mutants (a caveat if inhibitors of these targets are to be used clinically) [103]. It is also possible that these results reflect biases in the composition of the compound libraries screened.

Whatever the reason, the identification of these different series of inhibitors targeting various novel aspects of the biogenesis of the cell wall core of Mtb opens much needed new avenues for anti-TB drug development. Most importantly, the potency of INH, EMB, ETH, ISO, TAC, THL, d-cycloserine, β-lactams and that of recently identified inhibitors of DprE1, MmpL3 and a number of other targets cited throughout this review clearly highlight the assembly of the PG–AG–mycolic acid complex as one of the major Achilles’ heels of both actively replicating and persistent Mtb.

Conclusion

More than four decades after the discovery of the major first- and second-line anti-TB drugs, contemporary drug discovery projects employing target-to-drug and drug-to-target approaches keep pointing to cell envelope biogenesis as the target of choice. Importantly from a translational perspective, multiple novel targets impacting all major cell envelope components have been identified in this process (e.g., FAS-II dehydratases, DprE1, PknA, PknB, Rpf and LdtMt2, among others). The drug-to-target approach has also proven invaluable in uncovering as yet unknown and essential components of the cell envelope biosynthetic machinery (e.g., the trehalose monomycolate transporter MmpL3).

Future perspective

Considerable progress has been made in recent years in increasing the flow of novel anti-Mtb agents entering the drug development pipeline. Although encouraging, the number of new lead chemical entities is still too low to meet therapeutic needs. In particular, persister populations of Mtb still pose a significant challenge for TB control and the need for drugs capable of killing these populations of bacilli and shortening treatment duration remains a high priority [109]. The main advantages and disadvantages associated with the target-to-drug and drug-to-target approaches have been reviewed in detail recently [30]. Much of the current drug discovery efforts are focusing on cell-based screens. Expectations from these screens are high based on the number of compounds with novel modes of action that this approach has yielded over the last 8 years, some of which are now in various stages of preclinical and clinical development (Figure 7). Key to their success, however, will be the ability of the culture conditions used in the screening to reflect the variety of in vivo conditions encountered by the TB bacilli in humans. Based on what is now known of the metabolism of replicating and persistent bacilli, and of the changes that the cell envelope undergoes upon host infection [3-5,7-9,75], it is reasonable to predict that the number of novel cell envelope-related targets discovered through this approach will continue to grow. Beyond their therapeutic potential, the hope is that some of the novel inhibitors identified by random cell-based screening will allow missing enzymes, regulators, transporters and protein complexes involved in cell envelope biogenesis to be identified and lead to a better understanding of the physiology of Mtb during infection. Concomitantly, as our understanding of the basic physiology of Mtb in vivo progresses and target-to-drug technologies continue to advance, increasing numbers of target-based projects are likely to be pursued as well. At this point, combining classical target-based approaches with phenotypic screens to ensure that the identified hits are active against whole cells and on-target would be of great benefit, as this would address the issues of compound penetration and target vulnerability early on. Such approaches have become a reality with recent advances in controlling gene expression [66-68,110] and the availability of reporter systems to identify cell envelope inhibitors [69,70,91,111]. The renewed interest in target-based approaches is already clearly illustrated by the extraordinary developments that have occurred in the last 5 years in targeting novel aspects of the metabolism of PG and mycolic acids now known to be critical for cell division, cell integrity or the ability of Mtb to persist in vivo (e.g., d,d- and l,d-transpeptidases, resuscitation-promoting factors and Ser/Thr protein kinases). Independent of the type of approach used to identify new inhibitors, in vivo studies aimed at assessing their potential in animal models of TB infection should occur early on and accompany every step of their development to ensure that the most promising compounds are prioritized. Owing to the difficulty of mimicking the variety of in vivo conditions encountered by Mtb during host infection and the known lack of relationship between the antibacterial activity of TB drugs in vitro and in vivo, in vivo efficacy should indeed remain the driving criteria throughout the optimization process.

Supplementary Material

Executive summary.

The need for new anti-TB drugs

-

■

The rise in antibiotic-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and the fact that only one new antitubercular agent (TMC207/bedaquiline) has been introduced into clinical use in the last four decades emphasize the need for novel anti-TB agents with mechanisms of action different from those of existing drugs.

-

■

New drugs and drug regimens capable of efficiently killing persistent bacilli and reducing treatment duration remain a high priority.

The cell envelope of Mtb is the site of action of many first- & second-line anti-TB drugs

-

■

The unique cell envelope (lipo)polysaccharides and (glyco)lipids produced by Mtb play essential roles in the physiology and pathogenicity of this bacterium.

-

■

Their biosynthesis is the site of action of many of the current first- and second-line anti-TB drugs.

The search for novel drugs & the era of target-based approaches

-

■

After a period of a relative lack of interest for inhibitors targeting the cell envelope, the urgent need for new therapeutic strategies has driven renewed research towards a better understanding of the cell envelope, its biogenesis and role throughout the replicating, persistence and reactivation stages of Mtb.

-

■

As a result, new attractive drug targets were identified and pursued in the context of target-based screening and other target-based approaches, with different outcomes.

-

■

Peptidoglycan biosynthesis, in particular, was revealed as a key target with the potential to address the issues of persistence and reactivation.

Whole-cell screening efforts identify inhibitors targeting novel aspects of cell envelope biogenesis

-

■

The difficulty of identifying compounds whose inhibitory activity against purified targets translated to whole Mtb cell activity led many investigators in the field to return to cell-based screens.

-

■

This approach has led to the identification of many new classes of inhibitors, some of which are now in preclinical development.

-

■

Intriguingly, whole-genome sequencing of spontaneous resistant Mtb mutants identified multiple series of compounds targeting the decaprenyl-phosphoribose 2′ epimerase DprE1 and the trehalose monomycolate transporter MmpL3, required for the biogenesis of arabinogalactan/lipoarabinomannan and mycolic acids, respectively.

Future perspective

-

■

The number of new lead chemical entities is still too low to meet therapeutic needs.

-

■

Whole-cell screens are expected to dominate future screening endeavors and to identify more inhibitors targeting cell envelope-related processes.

-

■

Independent of the inhibitor screening approach, continued research towards a better understanding of the basic physiology of Mtb in vivo and the development of screening conditions that accurately reflect the physical environments encountered by TB bacilli in humans will be key to their success.

-

■

Cell envelope biogenesis remains an important reservoir of as-yet untapped targets for TB drug development.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all our colleagues whose important work could not be directly cited.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors’ research on cell envelope inhibitors is supported through NIH/NIAID grants AI064798, AI063054 and AI085992. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

-

■

of interest

-

■■

of considerable interest

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention: emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs worldwide, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2006;55(11):301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchison D, Davies G. The chemotherapy of tuberculosis: past, present and future. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2012;16(6):724–732. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhamidi S, Shi L, Chatterjee D, Belisle JT, Crick DC, McNeil MR. A bioanalytical method to determine the cell wall composition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown in vivo. Anal. Biochem. 2012;421(1):240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan GJ, Hoff DR, Driver ER, et al. Multiple M. tuberculosis phenotypes in mouse and guinea pig lung tissue revealed by a dual-staining approach. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham AF, Spreadbury CL. Mycobacterial stationary phase induced by low oxygen tension: cell wall thickening and localization of the 16-kilodalton α-crystallin homolog. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180(4):801–808. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.801-808.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Chastellier C, Thilo L. Phagosome maturation and fusion with lysosomes in relation to surface property and size of the phagocytic particle. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1997;74(1):49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glickman MS, Cox JS, Jacobs WR., Jr. A novel mycolic acid cyclopropane synthetase is required for cording, persistence, and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8■.Gupta R, Lavollay M, Mainardi JL, Arthur M, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein LdtMt2 is a nonclassical transpeptidase required for virulence and resistance to amoxicillin. Nat. Med. 2010;16(4):466–469. doi: 10.1038/nm.2120. Discovery of the nonclassical l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt2 that generates 3→3 linkages in the peptidoglycan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and demonstration of its therapeutic potential during the acute and chronic phases of infection.

- 9■.Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. Meropenemclavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. Demonstration that the combination of two US FDA-approved drugs, meropenem (a β-lactam) and clavulanate (a β-lactamase inhibitor), targeting peptidoglycan biosynthesis is effective against replicating and nonreplicating M. tuberculosis.

- 10.Lechartier B, Hartkoorn RC, Cole ST. In vitro combination studies of benzothiazinone lead compound BTZ043 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(11):5790–5793. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01476-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy VM, Einck L, Andries K, Nacy CA. In vitro interactions between new antitubercular drug candidates SQ109 and TMC207. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(7):2840–2846. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01601-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen P, Gearhart J, Protopopova M, Einck L, Nacy CA. Synergistic interactions of SQ109, a new ethylene diamine, with front-line antitubercular drugs in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58(2):332–337. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilcheze C, Baughn AD, Tufariello J, et al. Novel inhibitors of InhA efficiently kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3889–3898. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00266-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy VM, Einck L, Nacy CA. In vitro antimycobacterial activities of capuramycin analogues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52(2):719–721. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winder FG. Mode of action of the antimycobacterial agents and associated aspects of the molecular biology of mycobacteria. In: Ratledge C, Stanford J, editors. The Biology of the Mycobacteria. Academic Press; London, UK: 1982. pp. 353–438. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilcheze C, Jacobs WR., Jr. The mechanism of isoniazid killing: clarity through the scope of genetics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;61:35–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.111606.122346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson LA, Takayama K. Isoniazid inhibition of the synthesis of monounsaturated long-chain fatty acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1979;16:104–105. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee A, Dubnau E, Quémard A, et al. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozwarski DA, Grant GA, Barton DH, Jacobs WR., Jr Sacchettini JC. Modification of the NADH of the isoniazid target (InhA) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1998;279(5347):98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winder FG, Collins PB, Whelan D. Effects of ethionamide and isoxyl on mycolic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis BCG. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1971;66:379–380. doi: 10.1099/00221287-66-3-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishida CR, Ortiz De Montellano PR. Bioactivation of antituberculosis thioamide and thiourea prodrugs by bacterial and mammalian flavin monooxygenases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2011;192(1-2):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartkoorn RC, Sala C, Neres J, et al. Towards a new tuberculosis drug: pyridomycin – nature’s isoniazid. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012;4(10):1032–1042. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer L, Douglas JD, Baulard AR, et al. Thiolactomycin and related analogues as novel anti-mycobacterial agents targeting KasA and KasB condensing enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(22):16857–16864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grzegorzewicz AE, Korduláková J, Jones V, et al. A common mechanism of inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway by isoxyl and thiacetazone. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(46):38434–38441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikušová K, Slayden RA, Besra GS, Brennan PJ. Biogenesis of the mycobacterial cell wall and the site of action of ethambutol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39(11):2484–2489. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belanger AE, Besra GS, Ford ME, et al. The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11919–11924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi W, Zhang X, Jiang X, et al. Pyrazinamide inhibits trans-translation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2011;333(6049):1630–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1208813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimhony O, Cox JS, Welch JT, Vilchèze C, Jacobs WR., Jr. Pyrazinamide inhibits the eukaryotic-like fatty acid synthetase I (FASI) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2000;6(8):1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/79558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur D, Guerin ME, Skovierova H, Brennan PJ, Jackson M. Chapter 2: biogenesis of the cell wall and other glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2009;69:23–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30■.Sala C, Hartkoorn RC. Tuberculosis drugs: new candidates and how to find more. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(6):617–633. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.46. Contemporary review on the current approaches used in TB drug discovery.

- 31.Coxon GD, Cooper CB, Gillespie SH, McHugh TD. Strategies and challenges involved in the discovery of new chemical entities during early-stage tuberculosis drug discovery. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205(Suppl. 2):S258–S264. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott DE, Coyne AG, Hudson SA, Abell C. Fragment-based approaches in drug discovery and chemical biology. Biochemistry. 2012;51(25):4990–5003. doi: 10.1021/bi3005126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33■.Barry CE, Crick DC, McNeil MR. Targeting the formation of the cell wall core of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Dis. Drug Targets. 2007;7(2):182–202. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001808. Thorough review on the therapeutic potential of cell wall core biosynthetic enzymes.

- 34.Sivendran S, Jones V, Sun D, et al. Identification of triazinoindolbenzimidazolones as nanomolar inhibitors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enzyme TDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexopyranosid-4-ulose 3,5-epimerase (RmlC) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18(2):896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W, Jones VC, Scherman MS, et al. Expression, essentiality, and a microtiter plate assay for mycobacterial GlmU, the bifunctional glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase and N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate uridyltransferase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40(11):2560–2571. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singla D, Anurag M, Dash D, Raghava GP. A web server for predicting inhibitors against bacterial target GlmU protein. BMC Pharmacol. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tangallapally RP, Yendapally R, Lee RE, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of nitrofuranylamides as novel antituberculosis agents. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47(21):5276–5283. doi: 10.1021/jm049972y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurdle JG, Lee RB, Budha NR, et al. A microbiological assessment of novel nitrofuranylamides as anti-tuberculosis agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62(5):1037–1045. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rakesh, Bruhn D, Madhura DB, et al. Antitubercular nitrofuran isoxazolines with improved pharmacokinetic properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20(20):6063–6072. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Hess TN, Jones V, Zhou JZ, McNeil MR, Andrew McCammon J. Novel inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis dTDP-6-deoxy-l-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase (RmlD) identified by virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21(23):7064–7067. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leger M, Gavalda S, Guillet V, et al. The dual function of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis FadD32 required for mycolic acid biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 2009;16(5):510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergeret F, Gavalda S, Chalut C, et al. Biochemical and structural study of the atypical acyltransferase domain from the mycobacterial polyketide synthase Pks13. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(40):33675–33690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll P, Faray-Kele MC, Parish T. Identifying vulnerable pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using a knockdown approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77(14):5040–5043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02880-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galandrin S, Guillet V, Rane RS, et al. Assay development for identifying inhibitors of the mycobacterial FadD32 activity. J. Biomol. Screen. 2013;18(5):576–587. doi: 10.1177/1087057112474691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Favrot L, Ronning DR. Targeting the mycobacterial envelope for tuberculosis drug development. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2012;10(9):1023–1036. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warrier T, Tropis M, Werngren J, et al. Antigen 85C inhibition restricts Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth through disruption of cord factor biosynthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(4):1735–1743. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05742-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruning JB, Murillo AC, Chacon O, Barletta RG, Sacchettini JC. Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis d-alanine:dalanine ligase, a target of the antituberculosis drug d-cycloserine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55(1) doi: 10.1128/AAC.00558-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guzman JD, Wube A, Evangelopoulos D, et al. Interaction of N-methyl-2-alkenyl-4-quinolones with ATP-dependent MurE ligase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: antibacterial activity, molecular docking and inhibition kinetics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66(8):1766–1772. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molle V, Kremer L. Division and cell envelope regulation by Ser/Thr phosphorylation: Mycobacterium shows the way. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;75(5):1064–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magnet S, Hartkoorn RC, Szekely R, et al. Leads for antitubercular compounds from kinase inhibitor library screens. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2010;90(6):354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Danilenko VN, Osolodkin DI, Lakatosh SA, Preobrazhenskaya MN, Shtil AA. Bacterial eukaryotic type serine–threonine protein kinases: from structural biology to targeted anti-infective drug design. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011;11(11) doi: 10.2174/156802611795589566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lougheed KE, Osborne SA, Saxty B, et al. Effective inhibitors of the essential kinase PknB and their potential as anti-mycobacterial agents. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2011;91(4):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chapman TM, Bouloc N, Buxton RS, et al. Substituted aminopyrimidine protein kinase B (PknB) inhibitors show activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22(9):3349–3353. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalo Asensio J, Maia C, Ferrer NL, et al. The virulence-associated two-component PhoP–PhoR system controls the biosynthesis of polyketide-derived lipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(3):1313–1316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walters SB, Dubnau E, Kolesnikova I, Laval F, Daffé M, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR two-component system regulates genes essential for virulence and complex lipid biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;60(2):312–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frigui W, Bottai D, Majlessi L, et al. Control of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 secretion and specific T cell recognition by PhoP. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(2):e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalo-Asensio J, Mostowy S, Harders-Westerveen J, et al. PhoP: a missing piece in the intricate puzzle of Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JS, Krause R, Schreiber J, et al. Mutation in the transcriptional regulator PhoP contributes to avirulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryndak M, Wang S, Smith I. PhoP, a key player in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16(11):528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chesne-Seck ML, Barilone N, Boudou F, et al. A point mutation in the two-component regulator PhoP–PhoR accounts for the absence of polyketide-derived acyltrehaloses but not that of phthiocerol dimycocerosates in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190(4):1329–1334. doi: 10.1128/JB.01465-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, et al. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(23):19845–19854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sambou T, Dinadayala P, Stadthagen G, et al. Capsular glucan and intracellular glycogen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biosynthesis and impact on the persistence in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70(3):762–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalscheuer R, Syson K, Veeraraghavan U, et al. Self-poisoning of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting GlgE in an α-glucan pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6(5):376–384. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feltcher ME, Sullivan JT, Braunstein M. Protein export systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: novel targets for drug development? Future Microbiol. 2010;5(10):1581–1597. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6(1):29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei JR, Krishnamoorthy V, Murphy K, et al. Depletion of antibiotic targets has widely varying effects on growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(10):4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018301108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim JH, Wei JR, Wallach JB, Robbins RS, Rubin EJ, Schnappinger D. Protein inactivation in mycobacteria by controlled proteolysis and its application to deplete the β subunit of RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(6):2210–2220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park SW, Klotzsche M, Wilson DJ, et al. Evaluating the sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to biotin deprivation using regulated gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alland D, Steyn AJ, Weisbrod T, Aldrich K, Jacobs WR., Jr. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis iniBAC promoter, a promoter that responds to cell wall biosynthesis inhibition. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182(7):1802–1811. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1802-1811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee RE, Protopopova M, Crooks E, Slayden RA, Terrot M, Barry CE., 3rd Combinatorial lead optimization of [1,2]-diamines based on ethambutol as potential antituberculosis preclinical candidates. J. Comb. Chem. 2003;5(2):172–187. doi: 10.1021/cc020071p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. The chemical biology of new drugs in the development for tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010;14(4):456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tahlan K, Wilson R, Kastrinsky DB, et al. SQ109 targets MmpL3, a membrane transporter of trehalose monomycolate involved in mycolic acid donation to the cell wall core of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(4):1797–1809. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koga T, Fukuoka T, Doi N, et al. Activity of capuramycin analogues against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare in vitro and in vivo. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54(4):755–760. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nikonenko BV, Reddy VM, Protopopova M, Bogatcheva E, Einck L, Nacy CA. Activity of SQ641, a capuramycin analog, in a murine model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53(7):3138–3139. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00366-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaprelyants AS, Mukamolova GV, Ruggiero A, et al. Resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpf): in search of inhibitors. Protein Pept. Lett. 2012;19(10):1026–1034. doi: 10.2174/092986612802762723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.England K, Boshoff HI, Arora K, et al. Meropenem-clavulanic acid shows activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(6):3384–3387. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05690-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumar P, Arora K, Lloyd JR, et al. Meropenem inhibits D,d-carboxypeptidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;86(2):367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, et al. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by l,d-transpeptidation. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190(12):4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Erdemli SB, Gupta R, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G, Amzel LM, Bianchet MA. Targeting the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure and mechanism of L,d-transpeptidase 2. Structure. 2012;20(12):2103–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]