Abstract

Purpose of review

Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has undergone dramatic progression over the past year and continues to evolve as knowledge of the gastrointestinal microbiota (GiMb) develops. This review summarizes therapeutic advances in FMT, latest FMT therapies and presents the potential of FMT therapeutics in other gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal conditions.

Recent findings

The GiMb is now known to have a central role in the pathogenesis of many diseases. The success of FMT in curing Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is well established and preliminary findings in other gastrointestinal conditions are promising. Published data from over 500 CDI cases suggest that FMT is generally well tolerated with minimal side effects. The commercial potential of FMT is being explored with several products under development, including frozen GiMb extract, which has been shown highly effective in treating relapsing CDI. Such products will likely become more available in coming years and revolutionize the availability and method of delivery of GiMb.

Summary

Recent literature unequivocally supports the use of FMT in treating relapsing CDI. Trials are underway to determine the therapeutic potential of FMT in other conditions, particularly inflammatory bowel disease. Therapeutic FMT is a dynamic field with new and emerging indications along with ongoing developments in optimal mode of administration.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, colitis, Crohn's disease, faecal microbiota transplantation, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, sclerosing cholangitis

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the gastrointestinal microbiota (GiMb) with consortiums such as the Human Microbiome Project [1] and the European-based Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract (MetaHIT) established to investigate the resident microbiota of the human gastrointestinal tract. Studies resulting from these and other projects have helped elucidate the crucial role of microbiota in health homeostasis as well as disease pathogenesis and have altered the way we perceive the GiMb, no longer as just innocuous colonizers of our intestine but rather as active participants in determining human health and immune-mediated diseases. The GiMb has a much larger genome than its human host [2] and contributes to the development of various ‘diseases’ or ‘microbiota pathology’. The GiMb is akin to a tissue, as it is a collection of various cell lines. The human GiMb, similar to any other tissue or organ in the body, exhibits not only such features as ontogeny, anatomy and physiology, which will not be described in this short review, but also the capacity to suffer from various pathological conditions and perturbations. An important therapy used to ‘repair’ the GiMb is faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

Manipulation of the GiMb through FMT is not a new concept. Records document its use by Ge Hong 2000 years ago in China to treat food poisoning and severe diarrhoea [3]. The first published use in western medicine was in 1958 by Eiseman et al.[4] for pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Since then, it has been offered in only a few centres globally, though this has changed in the last few years with growing mainstream acceptance.

Box 1.

no caption available

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION: RATIONALE FOR USE

In the setting of increasing research and understanding of the GiMb, along with growing global concern regarding antibiotic resistance, it is not surprising that there is mounting interest in FMT therapy for disease states related to dysbiosis. The main advantage of FMT over other forms of microbial manipulation, for example antibiotics, prebiotics and probiotics, is that FMT provides the full spectrum of microbial organisms from a healthy individual and therefore can treat as yet uncharacterized dysbiotic conditions, while bypassing the need to decipher the complex compositional and functional pathogenic intricacies of the dysbiosis.

The rationale for use of FMT is perhaps best understood from a murine CDI model in which antibiotic damage of the microbiota permits invasion by Clostridium difficile. Lawley et al.[5] treated mice with clindamycin and then infected them with C. difficile 027/BI isolated from patients with CDI. The mice developed chronic disease with persistent dysbiosis, ongoing CDI and reduced GiMb diversity. FMT using homogenized faeces from healthy mice suppressed CDI, allowing recovery of health. Although the mouse model does not fully reflect the human condition, it allows us to see that antibiotic damage to the GiMb permits invasion via lowered colonization resistance. This applies not only to CDI but also to other opportunistic pathogens, which can become established once the integrity of the GiMb is compromised. There are probably numerous mechanisms by which the bacteria in an FMT function, including bacteriocin production to inhibit pathogen growth [6]. The CDI model, however, does not apply uniformly to other dysbiosis conditions. For example, in idiopathic ulcerative colitis, FMT fails to cure with a single infusion as it generally does in CDI, likely reflecting a more established and chronic dysbiosis that requires longer FMT administration to allow healing and regrowth of the micro-ulcerated colonic epithelium [7].

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION TREATMENT OF RELAPSING CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE INFECTION

The success of FMT in CDI has been well established in many case series [8▪,9,10] and one randomized controlled trial [11▪▪], which have been discussed extensively elsewhere [12▪,13,14] and therefore will only be summarized in this review. Initial treatment of acute CDI entails the withdrawal of any precipitating antibiotics, if possible, and treatment with metronidazole, vancomycin or fidaxomycin; relapsing infection is treated either with further metronidazole or vancomycin, or prolonged vancomycin treatment in ‘pulsed-tapered’ protocols [15]. Patients with a first posttreatment recurrence have up to a 40% chance of a second recurrence and a 65% chance of recurrence after the next antibiotic retreatment [16]. It is this high relapse rate coupled with the epidemic proportions of CDI [17] that prompted the use of FMT, which had been accumulating a growing body of successful case reports and case series [18,19]. A systematic review of FMT in CDI from 27 countries involving over 300 cases [20] reported excellent cure rates for relapsing CDI of around 90% via colonoscopy and enema with 76.5% cure rates via nasogastric infusion. Consequently, FMT is now a recommended treatment for the third recurrence of CDI [15]. Acute CDI and first relapse are still treated with antibiotics, which seems counter-intuitive, as antibiotics are used to treat a disease that largely results from antibiotic-induced disturbance of the GiMb. Given its efficacy and the very low complication rate of FMT, we predict an exponential increase in patients who have their first relapse treated with FMT, particularly when a simplified approved product such as encapsulated FMT oral therapy becomes available [13].

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION TREATMENT OF INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISAESE

Outside CDI, the greatest interest in FMT is as a potential therapeutic option in the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs).

Ulcerative colitis

Given the central role of GiMb dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of IBD [21], interest in FMT as a therapeutic option for ulcerative colitis is mounting. Case series suggest that it may be an effective therapy for some patients with ulcerative colitis [19,22,23,24▪,25,26], and formal randomized controlled trials are currently underway. Successful FMT for ulcerative colitis was first achieved in 1988 to reproduce in ulcerative colitis what Eiseman et al. [4] accomplished in pseudomembranous colitis. FMT treatment of this 1988 ulcerative colitis patient at the Centre for Digestive Diseases (CDD) resulted in durable clinical and histological cure to date of the patient's previously active disease. FMT was trialled as a treatment option for ulcerative colitis and other diseases at CDD, resulting in a case series that documented its use in 55 ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients [22]. Historically, the first FMT for ulcerative colitis was reported in 1989 by Bennet and Brinkman [27] who ‘proposed that bacterial metabolites of bile acids or cholesterol are involved in UC’ and carried out an ‘experiment implicating the colonic flora’ by demonstrating reversal of Bennet's severe ulcerative colitis of 7 years duration using FMT enemas. Bennet became asymptomatic for the first time in 11 years, with no active inflammation 3 months after FMT. In 2003, a further case series of six patients with ulcerative colitis was reported, documenting the complete clinical, colonoscopic and histological reversal of ulcerative colitis in all patients who previously had severe, relapsing ulcerative colitis [23].

In 2012, a retrospective review was conducted of 62 ulcerative colitis patients who had undergone FMT over a 24-year period at CDD [24▪]. This study reported a 91.9% response rate to FMT with 67.7% achieving complete clinical remission after FMT, defined as a 0–1 score on a modified Powell–Tuck Index; 24.2% achieved partial remission (defined as a ≥2 point decrease) and only 8% were nonresponders. In 12 of the 21 (57%) patients who had a repeat colonoscopy performed (mean follow-up time 33 months; range 1–198 months), normal mucosa was documented with absence of histological inflammation. Noting that ulcerative colitis requires multiple FMT infusions, such patients are now treated in CDD with the first FMT transcolonoscopically followed by daily enemas for 14 days, then second daily, X3 per week, X2 per week and ultimately weekly at each step for a period determined by clinical response with a colonoscopic review at 12 weeks but without a bowel lavage to preserve the therapeutic microbial luminal contents.

In a small phase 1 paediatric trial of FMT in 10 children and young adults with mild–moderate ulcerative colitis using five consecutive daily infusions [28▪], 33% achieved clinical remission at the end of 1 week and 78% had a clinical response, with 67% maintaining a clinical response at 4 weeks. Although these results are promising, they confirm that FMT response in ulcerative colitis is not as robust as in CDI, and again suggest that recurrent FMT infusions are required. In our experience, this needs to be continued for a minimum 14 days, but in many patients for weeks, to obtain durable results in ulcerative colitis. Exceptionally, some patients with ulcerative colitis may achieve cure with one to two FMT enemas.

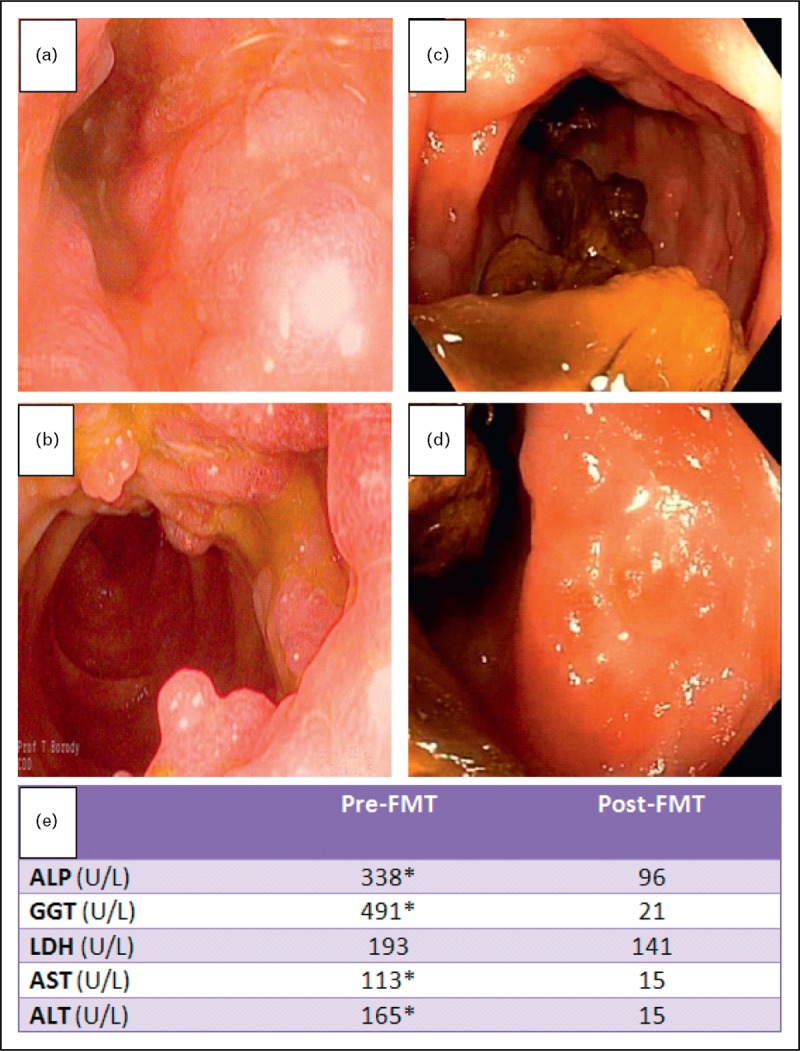

FMT in ulcerative colitis also potentially may have beneficial effects on the extraintestinal complications of the disease. Figure 1 relates to a patient with ulcerative colitis who not only showed improvement in colitis but also normalization of previously markedly elevated liver biochemical tests associated with sclerosing cholangitis, though no radiologic studies are available to confirm improvement.

FIGURE 1.

Inflammatory bowel disease with concurrent sclerosing cholangitis pre and post-FMT. A 38-year-old man with a 6-year history of ulcerative colitis, concurrent multiple sclerosis, sacroileitis and sclerosing cholangitis was treated with an initial transcolonoscopic FMT infusion, followed by over 100 FMT enemas during the next 12 months. After 4 weeks of daily FMT enemas, the patient's IBD symptoms had dramatically improved, liver biochemical tests had normalized and sacroileitis pain was absent. (a, b) Transverse colon and hepatic flexure (respectively), pre-FMT. (c, d) Transverse colon and hepatic flexure (respectively), post-FMT without bowel prep. (e) Liver biochemical tests immediately prior to FMT, and 12 months post-FMT.

Crohn's disease

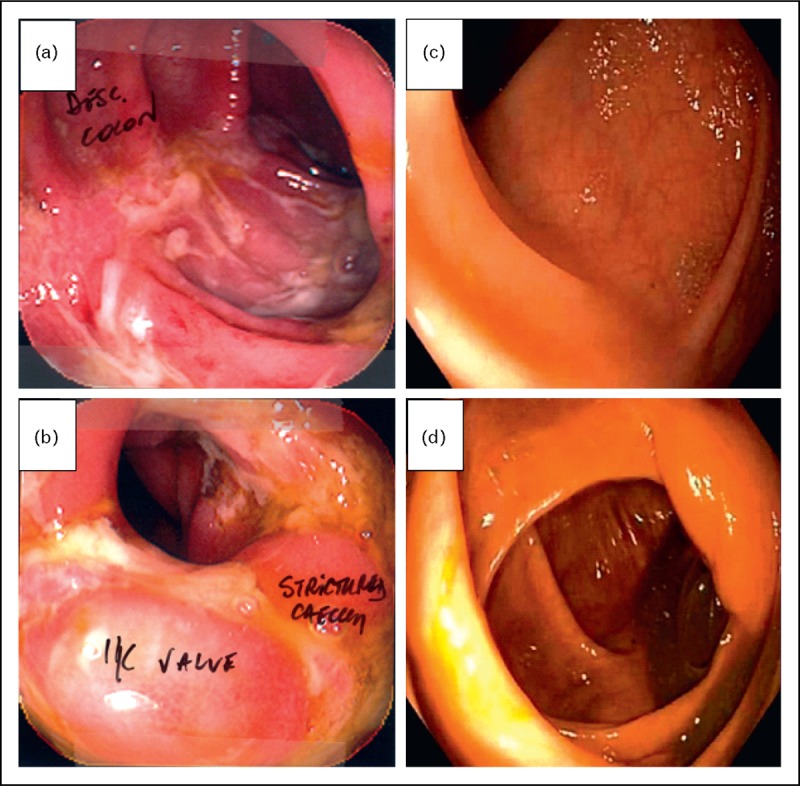

Available data on FMT in Crohn's disease are limited to case reports and small case series [22,26,29]. Vermeire et al.[29] reported no significant clinical or endoscopic improvement at 8 weeks in four patients with refractory Crohn's disease administered FMT via nasojejunal tube three times over a 2-day period. Transient recipient GiMb changes were observed in all patients (weeks 2–4) returning to baseline microbial composition by week 8. These findings along with other studies suggest that Crohn's disease has an increased resistance to FMT relative to ulcerative colitis, although preliminary data suggest that intensive, prolonged FMT may result in a clinical response and sustained GiMb transformation in some Crohn's disease patients. An illustrative case of terminal ileal Crohn's disease that normalized histologically has been published [30]. We present here an example of a patient with CDI and Crohn's colitis treated with FMT 12 years ago in whom not only the CDI but also Crohn's colitis was cured (Fig. 2). The implication of the influence of C. difficile and other infections or alterations in the GiMb on induction and maintenance of Crohn's disease activity is a subject of immense current interest.

FIGURE 2.

Crohn's colitis pre and postfaecal microbiota transplantation. A 46-year-old woman with a 2-year history of Crohn's colitis was treated with a single, large volume nasojejunal infusion of FMT over 6 h for concurrent CDI. (a, b) Descending colon and caecum (respectively), pre-FMT. (c, d) Descending colon and caecum (respectively), 12 years post-FMT. Stricture completely normalized.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

FMT has also been explored as a potential therapy for refractory IBS.

Faecal microbiota transplantation in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

Up to 30% of patients with IBS are thought to have acquired the condition after a bout of gastroenteritis, implicating a dysbiotic GiMb in at least this segment of IBS patients [31]. If the CDI pathogenicity model applies to IBS, then FMT also may be effective in this group of patients. Indeed, positive outcomes using FMT in IBS-D have been reported [22]. Pinn et al. [32] reported on 13 patients with refractory IBS (nine with IBS-D, three with IBS-C and one alternating IBS-D and IBS-C), 70% of whom had resolution or improvement in symptoms after FMT, including abdominal pain (72%), bowel habit (69%), dyspepsia (67%), bloating (50%), flatus (42%) and quality of life (46%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Faecal microbiota transplantation treatment in eight patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

| Patient | Pre-FMT condition | FMT regime | Post-FMT | |

| BW (78-year-old woman) | Symptom duration: >10 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | Three months post-FMT: | |

| • Chronic diarrhea (×years duration) | • Urgency | Oral vancomycin (500 mg b.i.d.), oral metronidazole (200–400 mg b.i.d.) for 9 months prior to FMT. | • Occasional diarrhoea | |

| • 4–6 stools/day | • Left iliac fossa (LIF) pain | FMT regimen: TC# infusion and 1 enema infusion | • ∼2 stools/day | |

| • Nocturnal stools | • Long-term loperamide (10 mg daily) | • 5 kg weight gain | ||

| • Incontinence | • Symptomatically much better | |||

| JG (40-year-old man) | Symptom duration: >3 years | FMT regimen: TC infusion and 9 enema infusions | Three months post-FMT: | |

| • Diarrhoea | • Nausea | • Marked improvement (75%) in bloating, tenesmus, feeling of incomplete evacuation, abdominal discomfort, nausea, joint pain and lethargy | ||

| • Bloating | • Joint pain | • Complete resolution of diarrhoea | ||

| • Tenesmus | • Lethargy | • No longer dairy intolerant | ||

| • Feeling of incomplete evacuation | • Malaise | |||

| • Abdominal discomfort | • Lactose intolerance | |||

| KP (49-year-old woman) | Symptom duration: > 4 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | Five months post-FMT: | |

| • Diarrhoea | • Flatulence | Oral vancomycin (250 mg mane, 500 mg nocte), oral rifaximin (200 mg b.i.d.) for 3 months prior to FMT. | • 1 stool/day | |

| • Occasionally explosive | • Decreased mental acuity | FMT regimen: TC infusion and 9 enema infusions | • 90% resolution of diarrhoea | |

| • Abdominal pain | • Daily nausea | • Improved food tolerances Markedly reduced bloating | ||

| • Extensive food intolerances | ||||

| BL (78-year-old man) | Symptom duration: 5 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | Three months post-FMT: | |

| • Diarrhoea | Oral vancomycin (500 mg b.i.d.) for 12 months prior to FMT | • Resolution of diarrhoea | ||

| • 2–3 watery motions/day | FMT regimen: TC infusion and 4 enema infusions | • 1–2 soft, formed motions/day | ||

| DH (51-year-old woman) | Symptom duration: 12 years | FMT regimen: TC infusion and 9 enema infusions | Six months post-FMT: | |

| • 1–12 watery motions/day | • Bloating | • Resolution of diarrhoea | ||

| • Abdominal pain | • Fatigue | • 2–3 formed motions/day | ||

| • Flatulence | • Decreased mental acuity | • Infrequent abdominal pain | ||

| • Increased energy | ||||

| BB (29-year-old man) | Symptom duration: 3 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | ||

| • Diarrhoea | • Severe urgency | Oral vancomycin (500 mg b.i.d.), oral metronidazole (200 mg b.i.d.) for 1 month prior to FMT. | • Resolution of diarrhoea, spare occasional episodic diarrhoea | |

| • 5 motions/day | • 10 kg weight loss | FMT regimen: TC infusion and 9 enema infusions | • Generally 1–2 motions/day | |

| • Abdominal cramping and pain | • Loperamide use to control symptoms | • Minimal pain | ||

| • Resolution of bloating. | ||||

| • Cessation of UC medication | ||||

| JM (58-year-old woman) | Symptom duration: > 28 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | Nine months post-FMT: | |

| • Explosive diarrhoea | • Up to 7 motions/day | Oral vancomycin (500 mg b.i.d.) | • 1–2 formed motions/day | |

| For 2 months prior to FMT | • Increased food tolerance | |||

| FMT regimen: TC infusion and 4 enema infusions | • Cessation of Loperamide and cholestyramine medications previously used to control diarrhoea | |||

| RB (60-year-old man) | Symptom duration: >15 years | Antibiotic pretreatment schedule: | 10 months post-FMT: | |

| • Long-standing diarrhoea | • Bloating | Oral vancomycin (250 mg b.i.d.), oral rifaximin (200 mg b.i.d.) for 2 months prior to FMT | • Intermittent symptoms: episodic diarrhoea with colicky pain, marked improvement | |

| • >10 watery motions/day | • Nausea | FMT regimen: TC + 4 enema infusions | ||

| • Severe abdominal pain | • Urgency | |||

| • Cramping | ||||

b.i.d., twice daily; FMT, faecal microbiota transplantation; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Faecal microbiota transplantation in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

Patients with IBS-C have been shown to have increased levels of sulphate-reducing bacteria compared with healthy controls [33] and methane-producing bacteria are also closely associated with constipation [34]. If IBS-C is similar to the CDI model wherein a pathogen produces toxins that inhibit intestinal motility, use of FMT could be a viable treatment option. Borody et al.[22] first documented that FMT could cure constipation and this was followed by a more complete case description showing reversal of symptoms, melanosis and dysmotility [35]. A case series was later published of 45 patients with IBS-C who were treated with transcolonoscopic FMT followed by FMT enema infusions of 17 cultured GiMb components. Immediately following the procedure, 40 of 45 patients (89%) reported relief in defecation, bloating and abdominal pain. Normal defecation, without laxative use, persisted in 18 of 30 patients (60%) contacted 9–19 months later [36].

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION IN AUTOIMMUNE CONDITIONS

Case reports suggesting possible therapeutic efficacy of FMT in autoimmune conditions exist, often noted as incidental phenomena detected during the use of FMT for CDI, ulcerative colitis and IBS.

Idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura

We have previously reported the unexpected reversal of idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura (ITP) in a patient with long-standing ulcerative colitis treated with FMT that resulted in prolonged normalization of platelet levels along with resolution of ulcerative colitis activity [37].

Multiple sclerosis

An infectious cause of multiple sclerosis (MS) has been speculated, though the potential for gastrointestinal pathogens to exert neurological effects remotely (as seen with many Clostridium species) has not been considered likely. In 2011, Borody et al.[38] reported three wheelchair-bound patients with MS treated with FMT for constipation. Bowel symptoms resolved following FMT; however, in all cases, there was also a progressive and dramatic improvement in neurological symptoms, with all three patients regaining the ability to walk unassisted. Two of the patients with prior indwelling urinary catheters experienced restoration of urinary function. In one patient of the three, follow-up MRI 15 years after FMT showed a halting of disease progression and ‘no evidence of active disease’.

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION IN METABOLIC DISEASES

A small, randomized, double-blind controlled trial demonstrated that FMT using stool from lean donors significantly improves insulin sensitivity in obese male individuals, with butyrate-producing intestinal bacteria increasing in intestinal samples [39▪]. These findings provide further evidence of a possible causal role for GiMb driving obesity, insulin resistance and perhaps hepatic steatosis [40–42].

FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION FOR OTHER CONDITIONS

There is also interest in FMT as a therapeutic option for conditions as diverse as halitosis, autism, chronic fatigue syndrome [43], nephrolithiasis, acne and for symptomatic relief in Parkinson's disease [44].

THE FUTURE OF FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANTATION

The GiMb is in the midst of a revolution in terms of research interest, our understanding and therapeutic potentials. There are several products extracted from whole stool, which is traditionally utilized for FMT, under development that are either approaching or are under review by the U.S. Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). These include both high-level extracts that contain the entire spectrum of human gastrointestinal microbes and cultured products with much smaller numbers of microbiota specifically developed and targeted to fulfill a particular indication (e.g. curing relapsing CDI) along with ‘cultured whole microbiota’ that may have broader applications.

CONCLUSION

The last few years have seen this ancient therapy that is elegantly simple and cost-effective in its purest form finally embraced by mainstream medicine as a genuine therapeutic option. The efficacy of FMT in CDI is unequivocal. It is actively being studied as a treatment option in other conditions including IBD, IBS and metabolic syndrome/insulin resistance. In coming years, as outcomes of trials become available, it is expected that indications for FMT will broaden and it will become more available and easily accessible. Incidental evidence of FMT benefit in comorbidities may further expand indications to conditions previously not associated with gastrointestinal dysbiosis and for which therapeutic GiMb manipulation may play a role. At the same time, we need to remain actively vigilant of any long-term safety issues that may arise from modification of the GiMb, as we expand FMT indications and its use becomes more prevalent.

Acknowledgements

Professor Thomas J. Borody has a pecuniary interest in the Centre for Digestive Diseases, where faecal microbiota transplantation is a treatment option for patients and he has filed patents in this field.

Conflicts of interest

Professor Lawrence J. Brandt has no financial interest or affiliation with any institution, organization or company relating to the manuscript.

Dr Sudarshan Paramsothy has no financial interest or affiliation with any institution, organization or company relating to the manuscript.

There was no funding received for this work from any organization.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

Footnotes

Correspondence to Dr Sudarshan Paramsothy, BSc (Med) MBBS (Hon I), MRCP (UK), FRACP, St Vincent's Hospital Clinical School, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010, Australia. Tel: +61 2 8382 2061; fax: +61 2 9712 1675; e-mail: sparam_au@yahoo.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, et al. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007; 449:804–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin J, Li R, Raed J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010; 464:59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang F, Luo W, Shi Y, et al. Should we standardize the 1,700-yearold fecal microbiota transplantation? Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauver AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery 1958; 44:854–859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawley TD, Clare S, Walker AW, et al. Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tvede M, Rask-Madsen J. Bacteriotherapy for chronic Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in six patients. Lancet 1989; i:1156–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swidsinski A, Weber J, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Spatial organization and composition of the mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:3380–3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8▪.Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, et al. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides evidence of the efficacy of frozen FMT in treating recurrent CDI, with equivalent response rates to fresh stool of approximately 90%.

- 9.Mattila E, Uusitalo-Seppälä R, Wuorela M, et al. Fecal transplantation, through colonoscopy, is effective therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, et al. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11▪▪.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the superiority of FMT over antibiotics in the treatment of recurrent CDI.

- 12▪.Brandt LJ. Intestinal microbiota and the role of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in treatment of C. difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A detailed review of the FMT in CDI.

- 13.Borody TJ, Brandt LJ, Paramsothy S, Agrawal G. Fecal microbiota transplantation: a new standard treatment option for Clostridium difficile infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2013; 11:447–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:478–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huebner ES, Surawicz CM. Treatment of recurrent Clostrium difficile diarrrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 2:203–208 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:409–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwan A, Sjolin S, Trottestam U. Relapsing Clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of homologous faeces. Lancet 1983; 2:845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borody T, Warren E, Leis S, et al. Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38:475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough E, Shaikh H, Manges AR. Systematic review of microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:994–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. Medical progress. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:417–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borody TJ, George L, Andrews P, et al. Bowel-flora alteration: a potential cure for inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome? Med J Aust 1989; 150:604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borody T, Warren E, Leis S, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis using fecal bacteriotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003; 37:42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24▪.Borody T, Wettstein A, Campbell J, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in ulcerative colitis: review of 24 years experience [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107 (S1):S665 [Google Scholar]; The largest series documenting FMT for ulcerative colitis.

- 25.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC. Long-term follow-up study of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for ulcerative colitis (UC) [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107 Suppl 1:1626S657 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JL, Edney RJ, Whelan K. Systematic review: fecal microbiota transplantation in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36:503–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennet JD, Brinkman M. Treatment of ulcerative colitis by implantation of normal colonic flora. Lancet 1989; 1:164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28▪.Kunde S, Pham A, Bonczyk S, et al. Safety, tolerability, and clinical response after fecal transplantation in children and young adults with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 56:597–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A phase 1 study suggesting that FMT for ulcerative colitis in a paediatric population is tolerated and can result in clinical response.

- 29.Vermeire S, Joossens M, Verbeke K, et al. Pilot study on the safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in refractory Crohn's disease [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:S360 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borody TJ, Paramsothy S, Agrawal S. Fecal microbiota transplantation: indications, methods, evidence, and future directions. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013; 15:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins SM, Chang C, Mearin F. Postinfectious chronic gut dysfunction: from bench to bedside. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 1 Suppl:2–8 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinn DM, Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ. Follow-up study of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for the treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [abstract]. ACG 2013 Annual Scientific Meeting and Postgraduate Course; 11–16 October 2013 San Diego, CA: San Diego Convention Center [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chassard C, Dapoigny M, Scott KP, et al. Functional dysbiosis within the gut microbiota of patients with constipated-irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35:828–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghoshal UC, Srivastava D, Verma A, Misra A. Slow transit constipation associated with excess methane production and its improvement following rifaximin therapy: a case report. J Neurogatroenterol Motil 2011; 17:185–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews PJ, Barnes P, Borody TJ. Chronic constipation reversed by restoration of the bowel flora. A case and a hypothesis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992; 4:245–247 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews P, Borody TJ, Shortis NP, Thompson S. Bacteriotherapy for chronic constipation-long term follow-up [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1995; 108:A563 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borody TJ, Campbell J, Torres M, et al. Reversal of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:S352 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borody TJ, Leis S, Campbell J, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in multiple sclerosis (MS) [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:S352 [Google Scholar]

- 39▪.Vrieze A, van Nood E, Holleman F, et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 2012; 143:913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A small controlled trial that suggests FMT can improve insulin sensitivity in patients with metabolic syndrome.

- 40.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006; 444:1027–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ley RE. Obesity and the human microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26:5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zupancic ML, Cantarel BL, Liu Z, et al. Analysis of the gut microbiota in the old order Amish and its relation to the metabolic syndrome. PLoS One 2012; 7:e43052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borody TJ, Nowak A, Torres M, et al. Bacteriotherapy in chronic fatigue syndrome: a retrospective review [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107 Suppl 1:S591–S592(A1481) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anathaswamy A. Fecal transplant eases symptoms of Parkinson's. New Sci 2011; 2796:8–9 [Google Scholar]